Safety flyer to the fishing industry - Our Sarah Jane

Published 8 December 2016

1. Summary

Fishing vessel Our Sarah Jane (NN710) fatal man overboard on 9 June 2016

2. Narrative

Our Sarah Jane

On 9 June 2016 a crewman on the 9.8m potter Our Sarah Jane was lost after he had jumped into the sea to cut a line that was fouling one of the vessel’s propellers.

At about 1200, the starboard propeller of Our Sarah Jane had been fouled by a string of pots as they were being shot away, and this effectively anchored the vessel in the middle of the English Channel. During the next 30 minutes the crew tried to reach and cut the backrope leading to the seabed, but the line was too taut to pull inboard using a grapple and it could not be reached even with a knife cable-tied to the end of a broom handle. As the vessel’s skipper was arranging for a nearby fishing vessel to assist, one of the vessel’s two deckhands took off his wellington boots and oilskins and jumped overboard to cut the backrope. He immediately started to struggle and was carried away from the vessel by a 2kts tidal stream.

The skipper tied a polysteel mooring rope to a lifebuoy and threw it towards the man overboard, but it fell short. The skipper then parted the backline by putting both engines ahead at fast speed, but when the vessel was manoeuvred close to the man overboard he was face-down and motionless. The lifebuoy was again thrown, but the man overboard did not respond. The other deckhand jumped into the water to assist but he also quickly got into difficulty and started to lose his strength. He was not wearing a lifejacket and was being weighed down by the polysteel rope from the lifebuoy, which he had used as a lifeline. The skipper pulled the deckhand back on board but, by then, the man overboard was no longer in sight. Despite an extensive air and sea search he was not found.

The MAIB investigation identified that the man overboard had possibly been using recreational drugs, and had jumped into the water despite the skipper instructing him not to do so. He and the other deckhand almost certainly suffered from cold water shock following immersion. In addition, the assistance to the man overboard was initially impeded by the vessel’s inability to manoeuvre, and valuable seconds were lost by not having at hand a lifebuoy with a lifeline already attached.

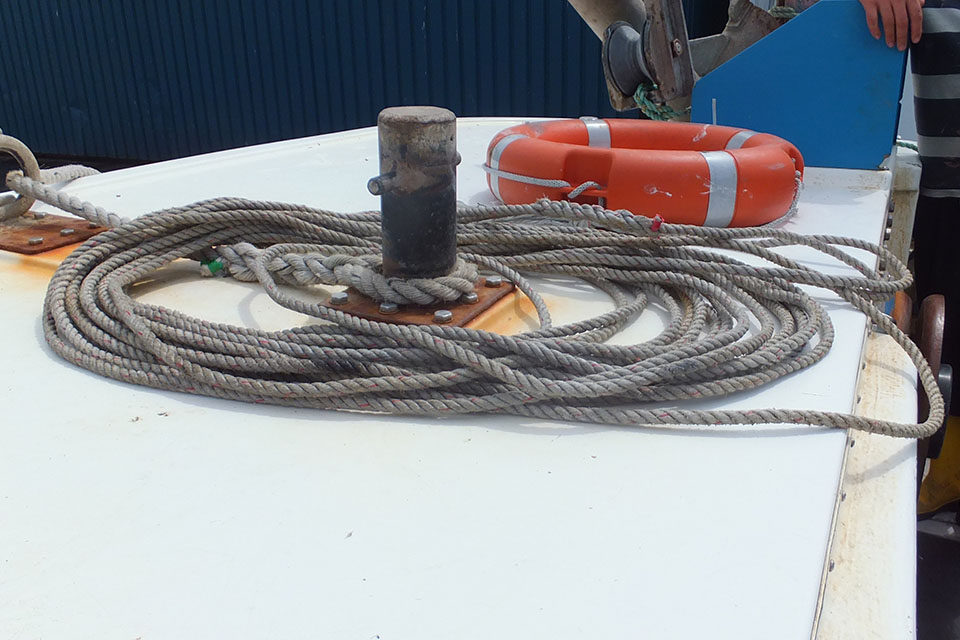

Lifebuoy and polysteel rope

3. Safety lessons

-

Many fishermen work long and unsociable hours in arduous conditions, which makes the use of recreational drugs appealing to some. However, drugs such as amphetamine are not only illegal, their effects on behaviour are potentially lethal on board fishing vessels. At sea, drug users put the lives of others at risk.

-

Cold water shock is a killer, and it can take effect in waters at a temperature of 15°C or below regardless of a person’s fitness, physique or swimming ability. Without a lifejacket to keep the head clear of the water, death can occur within minutes.

-

It is essential that lifesaving equipment is available in an emergency situation. However, over time, such equipment is frequently damaged, misplaced, or goes ‘out of date’. Owners and skippers should not rely on routine surveys to identify what is missing, but ensure they conduct regular checks to ensure the equipment will be available and effective if needed.

-

Drills help to ensure that crews are prepared to deal with a variety of emergencies. They can also contribute to the development of onboard plans and procedures for dealing with other emergencies such as loss of propulsion or a fouled propeller. Monthly emergency drills are not yet a regulatory requirement for all small fishing vessels, but it is intended that they will become mandatory in the near future.

-

Lifebuoys are simple and effective devices that are intended to provide buoyancy to persons in the water to prevent them from drowning. Do not delay in throwing the nearest one available to optimise their chances of survival.

-

Entering the water to assist an incapacitated person need not be unsafe provided the action is incorporated in a vessel’s manoverboard procedures. This means minimising the risk through the provision of appropriate equipment such as a dry suit or immersion suit, a lifejacket and a buoyant lifeline. Volunteers to enter the water should also be suitably trained and be aware of their role.

Our accident investigation report is available at: https://www.gov.uk/maib-reports/man-overboard-from-potter-our-sarah-jane-with-loss-of-1-life

For all general enquiries:

Marine Accident Investigation Branch

First Floor, Spring Place

105 Commercial Road

Southampton

SO15 1GH

Email iso@maib.gov.uk

Enquiries during office hours +44 (0)23 8039 5500