Review of the Seasonal Worker visa (accessible)

Published 16 July 2024

July 2024

Executive Summary

The agricultural sector’s reliance on migrant seasonal workers is, as we pointed out in 2018, unlike any other in the UK. There are obvious reasons why this is the case - physically demanding, low-wage seasonal work, in often rural locations far from population centres, can make the recruitment of domestic workers challenging. Wage differentials with poorer source countries can also make seasonal agricultural work in the UK an attractive and sometimes lucrative proposition for workers from overseas. The current Seasonal Worker Scheme (SWS) began life as a pilot in 2019 and will run until at least 2029.

A key argument for the existence of the SWS – other than shortage of local seasonal labour – is that of food security. Whilst achieving a high level of domestic food production is not inherently essential for ensuring food security, there is evidence of increasing pressure on food security due to climate uncertainty and geopolitical instability. The potential for increased automation – and a potential to reduce the sector’s reliance on migrant labour – is a key consideration when assessing the necessity of the scheme in the long term.

This review undertook an extensive range of quantitative and qualitative research to underpin our recommendations to government, including extensive stakeholder engagement, interviews, and data analysis. These are listed in more detail in the Introduction and in the associated Annexes. We are very grateful to employers, seasonal workers, scheme operators and other stakeholders for their engagement with this review.

Much of this research was undertaken whilst the future of the scheme was in doubt, prior to the announcement of a 5-year extension to the scheme (and an expected tapering of visa numbers in order to encourage automation and domestic recruitment) announced by the previous government in May 2024.

Our recommendations are structured around 5 broad ‘umbrella’ themes, namely:

-

Provide certainty around the future of the scheme – further certainty is required from government regarding the long-term future of the scheme, which can be achieved by confirming visa numbers and any further extension to the scheme on an annual basis – effectively giving employers and businesses 5 years’ notice if the scheme is to close. The criteria by which future visa numbers could be tapered must also be made clear. We do not recommend changes to the scheme’s eligible occupations.

-

Allow for a more flexible visa – greater flexibility would enable employers to plan more efficiently and for workers to maximise their earnings without adding complexity to the route. This can be achieved by shortening the current ‘cooling-off’ period from the current 6 months to 3 months and allowing workers to work any 6-month period in an individual calendar year.

-

Fairer work and pay for workers – a lack of pay data for those on the visa makes effective monitoring of pay very difficult. We recommend that Seasonal Workers are guaranteed at least 2 months’ pay in order to cover their costs in coming to the UK and reduce the risk that low-income workers are required to take. Workers are also subject to pension auto- enrolment and are typically eligible for a refund of income given their limited time in the UK that is subsequently difficult to process due to only being able to do so once they have finished employment and returned to their home country. This needs to be made clearer and simpler.

-

Tighten, communicate and enforce employee rights – Seasonal Workers coming to the UK are particularly susceptible to exploitation due to the nature of the work in often isolated rural areas, frequently with little or no English. Some are concerned that if they make a complaint, they may lose their visa and significant potential earnings. This means there is an inherent imbalance of power in comparison to employers. It is positive that many employers are undertaking significant steps to improve the welfare of those on the route, but there also appear to be a handful who are not doing so. Separately we have heard of instances of migrants paying significant fees abroad to unofficial agents or taking loans or otherwise accruing large debt.

To compound matters, the current enforcement landscape for Seasonal Workers is fragmented and does not offer an adequate safeguard of seasonal worker rights. We recommend a more coordinated approach between the bodies currently involved in worker welfare and a clearer delineation of responsibility for each. Worker rights must also be clearly communicated to workers in their own language, and we highlight where better data can be used to strengthen monitoring and enforcement. -

Give consideration to the Employer Pays Principle – Seasonal Workers currently bear the cost of both their visa and their travel to and from the UK; costs which can be considerable, and which increase the risk of debt bondage. Further work is needed to investigate how these costs might be more equitably shared along the supply chain.

Ultimately, we believe that if the government intends to maintain current levels of domestic food production then there is a clear need for a SWS in the short-to-medium term. This will provide certainty to businesses who operate in a sector unusually reliant on migrant labour, given the lack of domestic workers and the seasonal and rural nature of the work. If the new government wishes to reduce the reliance on migrant labour whilst maintaining domestic food production and supporting rural economies in the long-term, then it must ensure there are appropriate policies and an environment for encouraging automation of these roles.

Introduction

Aside from a short 5-year gap, a Seasonal Worker Scheme (SWS) for overseas workers to come to the UK has existed in one form or another since the end of the Second World War, with the current iteration – the SWS – having commenced as a pilot of 2,500 visas in 2019 in anticipation of the UK’s exit from the European Union (EU) and associated ending of Freedom of Movement (FoM) for EU nationals. This has left the SWS as one of the few remaining work routes for low-wage migrants to come to the UK. The sector’s historic reliance on migrant labour in lieu of a domestic workforce, and arguments around domestic food security, have previously been cited in justification for having such a scheme.

The scheme was expanded in 2020 to 10,000 places, and after the ending of FoM at the start of 2021 the scheme’s quota gradually increased year-on-year to 2024. The quota for 2023 and 2024 allows for at least 45,000 places per year in horticulture[footnote 1] (plus another 2,000 places for poultry workers), to be increased by 10,000 visas for horticulture workers “should there be demand”. The quota for 2025 will however see a slight reduction of horticulture visas to 43,000. Further detail for quotas to 2029 has not yet been set out.

Separate Seasonal Work Visas (SWVs) for the poultry sector were introduced in late 2021 following labour shortages in the sector. Horticulture SWVs allow workers to spend up to 6 months in the UK, whereas poultry workers are restricted to the Christmas peak season from October to December.

Given that the SWV had been in operation for several years, in March 2023, we wrote to the then- Minister for Immigration informing him of our intention to launch an inquiry into the scheme. Under the terms of the Framework Agreement between the Home Office and the MAC we are able, alongside commissioned work from the government, to engage in work of our own choosing and to comment on the operation of any aspect of the immigration system. The MAC had previously commented on the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Scheme (SAWS) in May 2013.

As we outlined in our letter, the aim of our review of the SWV is to assess its useability and impact for both employers and workers by considering the rules under which the scheme operates, the size and costs of the scheme, its economic rationale, the potential for exploitation and poor labour market practice, evidence from international comparisons, and the long-run need for such a scheme.

Our approach to this inquiry

As part of this review, we have sought information from a number of different sources to inform our research and support our decision making. These included:

-

Call for Evidence – We ran an online Call for Evidence (CfE) for around 13 weeks from June to October 2023, comprising 3 questionnaires aimed at employers, representative organisations, and those responding in a personal capacity. We received 83 unique responses, including from individuals who had direct experience of working on the scheme. Where Call for Evidence (CfE) respondents or interview participants have given percentages or monetary values in their quotes these have not been independently verified and, depending on the context, should on occasion be interpreted as the respondent’s way of expressing the order of magnitude of something rather than an exact figure;

-

Stakeholder engagement – Stakeholder engagement played a key role in our understanding of the issues around the SWV. Members of the MAC met with employers using the scheme and other meetings were held with key stakeholders including the Home Office, the Devolved Administrations, Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA), scheme operators, employer welfare organisations, and representative organisations in order to better understand the complexities facing the sector;

-

Primary research – We commissioned our independent research contractor, Revealing Reality, to undertake 30 in-depth employer interviews and site visits to enable observation of tasks, environment, processes, and speaking to managerial, supervisory and seasonal work staff. 12 one-hour interviews and 18 half-day site visits were conducted, with similar organisations using and not using the SWS paired as far as possible. To ensure diversity, the sample frame covered a variety of characteristics, including geography (all 4 nations of the UK), size of business and a number of additional characteristics that were monitored throughout the project to ensure a range of viewpoints. This research was supplemented with an additional 3 employer site visits carried out internally by members of the MAC Committee and Secretariat;

-

Kyrgyzstan research – We observed a Seasonal Worker recruitment event in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, and interviewed 28 prospective and returning Seasonal Workers, with one of whom we were able to conduct a follow-up interview once in the UK. We chose Kyrgyzstan because it has become a key source country for Seasonal Workers coming to the UK, and because of the timing of the recruitment event. We also met Kyrgyz government officials, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), and the British Ambassador to Kyrgyzstan;

- Data analysis – We undertook analysis of relevant datasets to examine a range of issues such as the size and characteristics of the workforce and the migrants within it. This included:

-

A review of UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) farm visit reports;

- A review of Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (Defra) Seasonal Worker Survey[footnote 2] data and Defra scheme provider Management Information (MI);

- A review of Home Office management information, including Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data; and,

-

- External evidence – We reviewed external reports and literature from a range of organisations that examine the scheme’s remit and structure, worker welfare, and future options. This includes publications from Focus on Labour Exploitation (FLEX), Workplace Relations Commission (WRC), the Association of Labour Providers, IOM, Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI), the House of Lords Horticultural Sector Committee, the House of Commons Library, government departments and others. We also engaged with overseas officials to enable comparisons with similar schemes operating in other countries and heard evidence from Professor Michael Winter of Exeter University on the topic of food security at a MAC meeting.

Structure of this report

Chapter 1 examines the reasons why we have a Seasonal Worker Scheme.

Chapter 2 outlines how the Seasonal Worker Scheme works.

Chapter 3 looks at the economic and social impact of the Seasonal Worker Scheme.

Chapter 4 looks at the impact of the Seasonal Worker Scheme on employers.

Chapter 5 explores Seasonal Worker welfare issues.

Chapter 6 details our conclusions and recommendations.

Further to the main report, the Annexes provide additional analysis, further information about the background to our approach, and a glossary of terms and abbreviations that we have used.

Chapter 1: Why do we have a Seasonal Worker Visa?

Summary

- The Seasonal Worker Scheme aims to address labour shortages within horticulture and poultry arising from varying seasonal demand.

- Farms find it challenging to recruit domestic workers to seasonal roles for various reasons, but most importantly because these roles are not available for the whole year.

-

Domestic production of affordable food is likely to be important for the UK’s food security in future due to climate and global geopolitical uncertainty.

- The previous government’s 2022 Food Strategy committed to maintaining food production levels in the UK. The Seasonal Worker Scheme helps to meet this commitment.

- Automation is a potential long-term solution that could reduce the need for seasonal labour within agriculture, however the development of machinery may require significant investment which individual farmers are unlikely to have sufficient capital for.

Introduction

The following chapter sets out the reasoning behind the operation of a Seasonal Worker Scheme for horticulture and poultry in the United Kingdom. It draws on data as well as evidence provided by various stakeholders including farm users of the scheme and seasonal workers themselves.

The rationale for this scheme arises from a significant within-year fluctuation in the demand for labour within horticulture and poultry. This is due both to the seasonality of crops and the changing demand for produce at Christmas. During the peak season, farms have consistently reported being unable to recruit sufficient domestic workers to meet their needs, resulting in a desire to employ willing and able migrant labour. Previously, farms were able to meet their seasonal labour requirements using EU workers who were allowed under Freedom of Movement (FoM) to live and work in the UK.

History and aims of the scheme

As set out in the MAC’s 2013 report, seasonal worker schemes in the UK originated after the Second World War and were designed to facilitate the movement of young people from across Europe to work in agriculture as an additional source of labour in peak season. Whilst the original purpose was to provide young people the opportunity for cultural exchange, the current version is now targeted at meeting the varying labour demand within the horticulture and poultry sectors.

The Seasonal Worker Scheme was closed in 2014 following MAC advice that EU expansion was likely to provide sufficient seasonal labour in the short term, and that continuance would represent preferential treatment for the horticulture sector. After the UK’s vote to leave the European Union in 2016 and in response to concerns within the farming industry in anticipation of the ending of FoM, in 2018 the previous government announced a pilot scheme to bring 2,500 workers from outside the EEA to work on UK farms for up to 6 months.

The MAC’s EEA report (2018) set out the logic behind the reintroduction of a Seasonal Worker Scheme alongside a recommendation that otherwise, sector-based schemes should be avoided and that any future Seasonal Agricultural Worker Scheme (SAWS) should ensure upward pressure on wages. A new version of SAWS called the Seasonal Worker Scheme (SWS) was subsequently piloted in 2019.

“The labour market for seasonal agricultural labour is completely separate from the market for resident workers in a way that is unlike any other labour market… According to the ONS, 99 per cent of seasonal agricultural workers are from EU countries and it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which this workforce can come from the resident labour market. There is no other sector in which the majority of workers are migrants… If there is no such scheme it is likely that there would be a contraction and even closure of many businesses in the parts of agriculture in the short run, as they are currently very dependent on this labour.”

EEA migration in the UK, Migration Advisory Committee, 2018

As shown in Figure 1.1 below, the increase in the visa quota since 2019 has coincided with a decrease in the number of EU workers within agriculture which has fallen from c.38,000 in the average month in 2019 to c.25,000 in 2023. To be clear, this captures all EU workers within agriculture and therefore includes both seasonal and permanent workers; it is possible that the reduced EU workforce is not distributed evenly across agriculture.

The observed decrease will not only be driven by reduced EU immigration post-FoM, but also an exit of EU workers previously working in the sector. The total number of Seasonal Worker Visas issued in 2023 was c.33,000, far below the absolute maximum 57,000 annual quota set by the previous government for both 2023 and 2024, of which 10,000 were a contingency only to be released if the government determined it was necessary. In 2025 this quota will be lowered to 45,000, reducing the maximum number of visas by a total of 12,000 including the removal of the 10,000 extension. There was no commitment from the previous government on the quota level beyond 2025, only a guarantee of the scheme’s operation until at least 2029 and an intention to reduce the quota across the period.

Figure 1.1: Seasonal Worker Visas issued and quota (left-hand axis), Change in EU workers in agriculture, indexed (2019=100, right-hand axis)

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU workers (agriculture forestry and fishing, 2019 = 100) | 100 | 89 | 79 | 73 | 67 |

| Quota (including extension) | 2,500 | 10,000 | 30,000 | 40,000 | 57,000 |

| Seasonal worker visas issued | 2,493 | 7,211 | 29,587 | 34,484 | 32,724 |

Source: Home Office immigration stats, 2019-2023 and ONS UK payrolled employments by nationality, region, and industry, 2023.

Agricultural labour market

Seasonality of agriculture

In 2023, employment within agriculture, forestry and fishing was relatively low compared to other industries and accounted for <1% of total employment in the UK. Employment within UK farming is cyclical, with demand for workers changing based on season; there is a clear within-year fluctuation that demonstrates the seasonality of work within this industry as crops ripen. During 2023, employment within agriculture, forestry and fishing peaked 17% higher than the baseline, with this variation reducing slightly since 2015 from 23%, suggesting a slight smoothing of labour demand. As shown in Figure 1.2, this difference is most stark for non-EU and EU nationals, compared with UK nationals, which peak 134% and 51% higher than the month with the lowest employment. Comparatively, the percentage change in employment of UK nationals stays relatively consistent across the year. However, when looking at absolute figures the difference between maximum and minimum employment levels is greater for UK nationals than both EU and non-EU nationals.

Focusing on employment of foreign workers within agriculture, in recent years there has been a shift from EU workers to non-EU workers, as shown in Table 1.3. This decline in the number of EU nationals is not limited to seasonal workers, and applies to all EU born workers within agriculture, forestry, and fishing. The fall in EU workers is offset by a relative rise in the number of non-EU and UK nationals working within the sector. Looking at seasonal workers specifically, based on a survey of growers, the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (Defra) estimated that in 2022, 87% of seasonal workers not recruited through the visa were EU settled status workers, with this falling to 79% in 2023.

Figure 1.2: Change in employment within agriculture, forestry, and fishing split by nationality, 2023

Figure 1.2: Change in employment within agriculture, forestry, and fishing split by nationality, 2023

| Month | UK nationals | EU nationals | Non-EU nationals |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 1.02 | 1.06 | 1.00 |

| February | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1.04 |

| March | 1.01 | 1.23 | 1.08 |

| April | 1.02 | 1.28 | 1.27 |

| May | 1.03 | 1.39 | 1.60 |

| June | 1.07 | 1.50 | 2.15 |

| July | 1.09 | 1.51 | 2.34 |

| August | 1.10 | 1.46 | 2.30 |

| September | 1.10 | 1.38 | 2.19 |

| October | 1.08 | 1.26 | 1.90 |

| November | 1.06 | 1.12 | 1.42 |

| December | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.15 |

Source: UK payrolled employment by nationality, region, and industry, HMRC 2023.

Note: Employment is indexed so that 1 = month with minimum employment for that nationality.

Table 1.3: Employment in agriculture, forestry, and fishing split by nationality, average month

| Nationality | 2016 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| UK | 79% | 81% |

| EU | 20% | 13% |

| Non-EU | 1% | 6% |

Source: UK payrolled employment by nationality, region, and industry, HMRC 2023.

The seasonal nature of farming discussed above results in the varying labour demand within year demonstrated in Figure 1.2 and therefore, a reliance on flexible labour.

We observe from Defra’s surveying of farmers that in 2023 the agricultural workforce across England, Scotland and Northern Ireland was c.412,000, of which c.53,000 (around 13%) were defined as “seasonal, casual or gang”. Home Office visa data shows that in 2023, 33,000 Seasonal Worker Visas were issued. This would suggest that around 62% of “seasonal, casual or gang workers” were recruited through the SWS. The rest of the agricultural labour force is made up of contracted employees who are guaranteed a certain number of hours throughout the year, as well as farmers, business partners and directors.

Table 1.4: Agricultural workforce, number of people, 2023

| England | Scotland | Wales | Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers, business partners and directors | 179,000 (61%) | 42,000 (62%) | 38,000 (76%) | 41,000 (77%) |

| Regular employees | 77,000 (26%) | 17,000 (25%) | nc | 4,000 (8%) |

| Seasonal, casual or gang labour | 37,000 (13%) | 8,000 (12%) | nc | 8,000 (15%) |

| Total labour force | 292,000 | 67,000 | 50,000 | 53,000 |

Source: Structure of the agriculture industry, Defra 2024.

Note: Wales did not provide data on the number of regular employees/seasonal, casual or gang labour. Totals may not sum due to rounding. As per Defra data, ‘Farmers, business partners and directors’ also includes ‘spouses’.

As shown in Figure 1.5 below, in recent years there has been an increase in the proportion of the casual workforce on the Seasonal Worker Visa (SWV). At the same time, since 2019 total employment of seasonal, casual or gang labour has been consistent. In other words, since its reintroduction, the SWS has substituted for workers with other statuses, such as EU citizens who arrived under FoM.

The change in the characteristics of seasonal workers is something that was referenced within our stakeholder engagement, fieldwork, and Call for Evidence (CfE). Employers told us they had seen a decline in their ability to recruit from various sources as a result of the ending of FoM. This included workers from the EU population resident in the UK (as they returned to their home countries, aged out of the labour market or moved on to other jobs); from the wider personal networks of these workers, which prior to the ending of FoM had been an important source of word-of-mouth recommendation for both employers and employees; and from workers who had preferred to live elsewhere in the EU and work in the UK seasonally. Although many within these groups of workers had applied to the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS), employers stressed that this was a rapidly dwindling pool of labour:

“At the start of the 2021 season, we had a sizeable pool of 1,900 potential seasonal workers who had EUSS status and had previously worked for [us]. Historically [we have] aimed for a 75 - 80% returnee rate [from this pool of workers], 2021 this % dropped to 46%, we had far fewer applications and obviously significantly less people arrive for work. Since 2021 our experienced EUSS status seasonal employees have reduced by 50% year on year. For 2023 we have employed a total of 319 seasonal employees with EUSS, this includes several new starters. This vastly differs from the 2,600+ EU residents [we] were employing in 2015- 2020. We believe that within 2 years this recruitment stream will disappear and no longer be a viable option for our harvesting operations.”

Large edible horticulture user, multi-site organisation, CfE respondent

Figure 1.5: Seasonal, casual or gang labour split into those on the seasonal worker visa, thousands

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seasonal labour on Seasonal Worker Visa | 2 | 7 | 30 | 34 | 33 |

| Seasonal, Casual or gang labour not on Seasonal Worker Visa | 60 | 50 | 25 | 23 | 20 |

Source: Home Office immigration stats, 2024 and structure of the agriculture industry Defra, 2024

The labour intensity for each farm type, split by casual and regular workers is visualised below. Horticulture is currently by far the most labour-intensive sector within farming and uses the most casual labour, with 5.8 regular workers and 3.9 casual workers per farm. It is therefore not surprising that the SWV is mainly targeted at the horticultural sector. However, this labour requirement is not fixed, and it is possible this could be reduced with additional automation within horticulture, something discussed in more detail later.

Figure 1.6: Labour intensity by farm type, workers per farm, England, 2023

| Farm Type | Regular workers per farm | Casual workers per farm |

|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 2.56 | 0.21 |

| General cropping | 1.96 | 0.49 |

| Horticulture | 5.75 | 3.90 |

| Specialist pigs | 3.29 | 0.13 |

| Specialist poultry | 3.68 | 0.29 |

| Dairy | 4.42 | 0.21 |

| Grazing livestock | 2.09 | 0.11 |

| Mixed | 2.78 | 0.19 |

| Other/unclassified | 1.54 | 0.07 |

Source: Structure of the agriculture industry Defra, 2024.

Note: Due to a lack of data, the above graph only covers the farms within England. Regular workers are defined by as both part-time and full-time workers with contracted hours. Casual workers are defined as workers who do not have guaranteed contracted hours.

Horticulture and Poultry

The SWV is currently only available to foreign workers wanting to undertake jobs within horticulture (ornamental and edible), or poultry farming. This is partly due to the reliance within horticulture on casual labour (see Figure 1.6). See Chapter 2 for a further discussion on the rules of the scheme.

It is interesting to note the relative importance of domestic production within total supply of horticulture and poultry. In 2023, 53% of the total supply of vegetables in the UK was produced domestically, with the number being much lower for fruit (16%). Meanwhile, almost all of the UK’s supply of poultry (82% in 2023) and around half of the UK’s supply of ornamentals (55%) are produced domestically.

Links to other government policy

Rationale for seasonal work - Food security

The level of food produced domestically can affect the UK’s food security. There is an argument that, despite a relatively small contribution to the UK economy (as discussed in Chapter 3), agriculture plays a public value role in maintaining food security through supporting domestic food production levels.

Food security is defined by Defra as “ensuring the availability of, and access to, affordable, safe and nutritious food, sufficient for an active lifestyle, for all, at all times”. An important point here is that self-sufficiency is not the same as food security; in a situation where the UK was 100% self-sufficient in the production of fruit and vegetables, if supply chain issues arose (such as a new pest killing a large number of crops) our overreliance on domestic production would make the UK less food secure.

As referenced in the previous government’s food strategy, being part of a global food system improves our food security by diversifying our supply sources, giving us access to products that cannot be produced domestically and allowing comparative advantage to provide us with cheaper products. This is not to say there is no societal benefit in the domestic production of food. Evidence provided by Professor Michael Winter of Exeter University suggested that a climate of political uncertainty and the influence of climate change on salination, water shortage and soil erosion means that any over- reliance on sourcing food from other countries is vulnerable to potential shock. A balance is therefore needed where we support enough of our domestic industry so that we are not dependent on other places, whilst also not subsidising unproductive domestic production and missing out on a variety of fruit and vegetables as well as the potential gains from comparative advantage.

Professor Winter’s evidence also set out that, should a decision be made not to support the UK agricultural industry and allow parts of it to “die out”, it could be very difficult to bring those parts back in the future: the land may have been repurposed for other uses and no longer suitable for agriculture, or the relevant industry skills may have been lost. This means there are potential risks in reducing the size and scale of the UK’s agricultural industry, especially in the context of climate change and geopolitical uncertainty where domestic food production could become a more significant factor in maintaining food security.

It is likely that in the future, the domestic production of fruits and vegetables will benefit the food security of the UK through helping to ensure the availability of safe and nutritious food. This societal ‘food security’ benefit provides some justification for government support in the agricultural (and specifically) horticultural industry.

Rationale for Seasonal Work - ‘Flower’ security

The previously discussed food security benefits clearly do not apply to ornamental horticulture, which it could be argued is more like other seasonal industries (such as retail) which do not have schemes allowing preferential immigration access; in isolation there is no clear justification for ornamental horticulture’s inclusion on the scheme.

However, in practice, the inclusion of ornamental horticulture supports the edible sector by providing alternative and complementary workstreams. For example, the daffodil season occurs at the beginning of the year before the main edible crops need workers, the inclusion of ornamentals encourages seasonal workers into the country earlier and provides a ready migrant labour supply at the start of the edible season. It also provides seasonal workers the opportunity to pick up additional hours, should the crops for which they were originally booked start later or finish earlier than expected. There is little evidence of competing demand for workers between ornamental and edible horticulture, given that visa quotas have not been met, rather it is much more likely the demand for workers is complementary (the ornamental sector’s inclusion benefits the edible horticulture sector).

The conclusion that can be drawn from this is that there is limited opportunity cost to ornamentals’ inclusion on the scheme and therefore, preventing ornamental producers from recruiting using the scheme would likely create no benefit.

Government food strategy

The previous government’s food strategy (June 2022) set out 3 key objectives:

-

A prosperous agri-food and seafood sector that ensures a secure food supply in an unpredictable world and contributes to the levelling up agenda through good quality jobs around the country;

-

A sustainable, nature positive, affordable food system that provides choice and access to high quality products that support healthier and home-grown diets for all; and,

-

Trade that provides export opportunities and consumer choice through imports, without compromising our regulatory standards for food, whether produced domestically or imported.

To achieve these objectives, the strategy suggests the UK “broadly maintain(s) the current level of food we produce domestically” and “ensures by 2030, pay, employment and productivity will have risen in the agri-food industry”.

In May 2023, during a ‘farm to fork summit’ the then Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, made a commitment in response to this to broadly maintain current food production levels where the UK produces c.60% of all the food it requires. At a speech to the National Farmers’ Union conference in February 2024, he vowed to focus on food security and outlined plans for an annual Food Security Index, with a focus on specific produce e.g., that 15% of all tomatoes are produced domestically).

In other words, the previous government were committed to maintaining domestic food production levels. This has important implications for the SWV, which will have an impact on the ability to meet these commitments.

Rationale for Seasonal Work - Lack of domestic labour

Shortage of available workers

Seasonal agriculture has historically been highly dependent on migrant workers. We currently have a reasonably ‘tight’ labour market (where vacancies are high relative to unemployment), but this is not the main cause of employers’ difficulty filling seasonal worker roles. For example, in 2020, there was an increase in unemployment and a fall in vacancies, indicating a weaker labour market, but the ‘pick for Britain’ scheme launched around this time failed to attract a significant number of British workers, as discussed further in Chapter 4.

Employers’ difficulty attracting workers even during periods of higher unemployment could be due to a number of factors. In addition to the relative unattractiveness of some roles, which can often require challenging manual labour in cold, muddy conditions, seasonal jobs are only available for part of the year. Workers prefer permanent jobs with more stability and better long-term prospects, and in a tight labour market these options exist.

Many jobs within the sector offer relatively low pay. The table below compares pay in the main occupations seasonal workers work in (horticultural trades and farm workers) with competing occupations. These were identified by looking at the occupations without privileged immigration access and with the same minimum educational requirements as seasonal worker occupations, which had the most vacancies in 2023 across all Local Authority Areas (LAA) with 3 or more farms that have used the SWV. This analysis is not to say the following roles are comparable with seasonal work, rather they are competing with farms for labour. Table 1.7 shows, that whilst pay for ‘farm workers’ and ‘horticultural trades’ is low when compared to the whole economy, it is relatively consistent with pay rates for competing occupations. This suggests pay would not be a deciding factor for individuals to pursue these occupations (as others are available at similar rates). Further, the reliance on migrant labour suggests that pay is not sufficiently high to attract British workers to these roles. It is important to note, the median wage data presented for Horticultural Trades and Farm workers is for the whole occupation not seasonal workers specifically, who may be paid at a different rate.

Table 1.7: Median hourly wage

| Occupation | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| All employees | £14.10 | £14.80 | £15.90 |

| Cleaners and Domestics | £9.30 | £10.00 | £10.90 |

| Sales Related Occupations n.e.c. | £10.50 | £11.20 | £12.10 |

| Customer Service Occupations n.e.c. | £10.30 | £11.10 | £12.20 |

| Sales and retail assistants | £9.60 | £10.10 | £11.00 |

| Kitchen and Catering Assistants | £9.00 | £9.80 | £10.60 |

| Warehouse Operatives | £10.40 | £11.10 | £12.10 |

| Horticultural trades* | £10.40 | £11.10 | £11.30 |

| Farm Workers | £10.00 | £10.70 | £11.10 |

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Employment (ASHE) and Lightcast’s ‘Analyst’ platform (to identify competing occupations).

Note: Horticultural trades and farm workers included as they are the most common Seasonal Worker Visa occupation codes. Wages have been rounded to the nearest 10 pence.

- Indicates a CV of >5%, <=10%, meaning estimates are considered ‘reasonably precise’.

Geographical Immobility of Labour

In the recruitment of domestic labour, farms have local geographic barriers that must be overcome. Most farms that use seasonal workers are situated in rural, sparsely populated areas, where there may be relatively small local available labour pools, not only due to the relatively low population but additionally, rural areas have comparatively lower levels of unemployment compared to urban areas (evidenced by the correlation of population density to claimant count rate). Furthermore, there are issues around an ageing population in rural areas. This could be a challenge for farms’ recruitment as much of the work is physical and therefore suited to younger workers.

The table below shows some key labour market statistics for the LAA with the highest number of farms that use the SWS (Unitary Authority data is presented where LAA are unavailable). Whilst there is no consistent acute labour market issue that would explain farms’ recruitment struggles, it is interesting to note that each Unitary Authority/Local Authority (UALA) specified is below the UK median UALA for population density and has roughly the same or higher average age than the rest of the UK. As seen in the case study at the end of this section, the converse (being near a town or city with a population of younger casual workers) was key for those employers who were not struggling with recruitment. One should be cautious about deriving strong conclusions from the analysis below, as some of the areas specified are relatively large and likely to have variation of local labour market conditions within area.

Table 1.8: Area characteristics of top Local Authority Areas that use the Seasonal Worker Visa

| Unitary Authority/Local Authority Area (UALA) | Population Density (and percentile) | Average age (mean) | Unemployment rate | Average wage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herefordshire | 87 (11) | 51 | 1.8 | £14.00 |

| Fife | 280 (27) | 41 | 4.0 | £15.90 |

| Kent* | 449 (40) | 41 | 3.5 | £16.50 |

| Perth & Kinross | 29 (4) | 44 | 3.2 | £17.10 |

| Worcestershire** | 350 (33) | 43 | 3.7 | £15.30 |

| Angus | 53 (7) | 47 | 2.5 | £15.90 |

| Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly*** | 162 (20) | 45 | 2.0 | £14.10 |

| UK | 279 | 40 | 3.5 | £15.90 |

Source: Annual Population Survey Jan-Dec 2022. Location of farms derived from Defra operator data 2022.

Note: UALA appear in descending order of number of farms that use the Seasonal Worker Visa. Wages are rounded to nearest 10 pence.

*Maidstone is the desired Local Authority Area (LAA), data is presented for Kent.

**Wychavon is the desired LAA, data is presented for Worcestershire.

***Cornwall is the desired LAA, data is presented for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly.

It may also be difficult to recruit labour from further afield. Firstly, there are often poor public transport links to rural locations which may make it challenging to commute unless workers have access to a car. Moreover, often individuals living in urban areas will have more job options closer to home at a similar or higher wage, and the ‘seasonal worker package’ may be less attractive.

“In our location, unemployment is less than 4% and those people reject work in agriculture mainly because they have no transport to get to our rural location and/or we are not able to offer 12 months of the year working. We have tried very hard to recruit locally, it would be very convenient to do so but there are just no people interested to take up our seasonal work. We advertise in the various job centres throughout the harvest season.”

Medium edible horticulture user, West Midlands, CfE respondent

Ability to encourage domestic workers

Whilst we have argued that poor conditions discourage UK workers from undertaking seasonal work, this in itself is not a sufficient precondition for favoured access to the immigration system. In general, we would expect that, in response to workers’ reluctance to undertake seasonal work, employers should increase wage rates/benefits to a point where workers would be willing to work in these roles. We have found some evidence that there is limited scope within the sector for pay increases that would be significant enough to encourage domestic participation in seasonal work.

Some employers told us that there may be restrictions in their ability to increase the hourly rate due to tight margins, something also mentioned in the previous government’s Independent Review into labour shortages in the food supply chain. The House of Lords report into the horticultural sector argues that this is a result of loss-leader pricing strategies in supermarkets which leads to poor grower returns within the horticultural sector. One could conclude from this that supermarkets should just charge more to improve growers’ margins and allow for the recruitment of domestic workers at higher wage rates; however, it is not as simple as that. UK producers compete with imports and, without further market intervention such as tariffs, an increase in the price of domestically produced food will likely lead to consumers choosing imported food over ‘home-grown’. This global competition limits how much employers can pass on additional costs to customers.

There may be strategies that can assist farms’ domestic recruitment to some extent, for example by using domestic recruitment agencies or smoothing workload throughout the year, something that is discussed in more detail within Chapter 4. However, these strategies are more feasible for some employers to implement than others and they are unlikely to reverse the sector’s overwhelming reliance on migrant workers in seasonal jobs.

Case Study: Impact of location on ability to recruit

We heard evidence from a large ornamental horticulture grower in the south of England who were able to meet much higher demand for labour around Christmas by recruiting through local temporary work agencies. This was because they are based near a city with a large population: the farm is only about twenty minutes’ travel time from the city, which they argued appealed to workers living there. It should be noted that many of the workers they were able to recruit were still from other countries.

In contrast, a similar size and type of business (a medium-sized ornamental horticulture grower) in a more rural area, struggled to recruit locally. They advertised via the Jobcentre and only had three responses from workers based in the UK.

*This case study is based on fieldwork from Revealing Reality

Seasonal Worker Schemes globally

The UK is far from unique in having a seasonal worker scheme. Many EU countries have similar schemes, as do other countries such as the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Whilst this does not conclusively demonstrate the necessity of the scheme in this country, it shows that the issues around motivating domestic labour forces to undertake seasonal work are also experienced elsewhere. In Ireland, for example, a horticultural pilot scheme will take place in 2025 as a result of increasing difficulties in sourcing seasonal agricultural workers from within the EU. Officials cite increased competition for workers from other European countries, and a reduction in the numbers of EU seasonal workers from Eastern Europe where domestic economic development has reduced the attractiveness of seasonal work abroad. Similarly, Poland – for many years a sending country for agricultural workers – has since 2018 operated its own Seasonal Worker route.

The evidence we have received suggests at the prevailing pay rates, domestic workers are unwilling to undertake seasonal work on farms, and it is unlikely that farms will be able to meet their seasonal labour demands using the domestic workforce. This means, employers must either fill the vacancies with migrant seasonal workers who are willing and able to undertake the work, shift towards automation to reduce reliance on labour, or move away from labour-intensive produce that requires seasonal workers (either to alternative crops/livestock or into other industries). Many users of the scheme say that without the scheme they would not be able to continue to operate.

“Without these visa employees we would have no business, certainly not of this nature. We are one of the largest direct growers of fresh produce to supply supermarkets in the UK and I can only but stress how critical a scheme like this is in absence of free movement of labour across borders. The UK fresh produce industry can’t survive without them - it’s that simple.”

Large edible horticulture user, Scotland, CfE respondent

Alternatives to migrant seasonal labour – Automation

Aside from migrant labour, an alternative solution to a lack of willing and able domestic workers would be to invest in automation processes which could reduce the horticulture sector’s current reliance on seasonal labour. Improving automation also has the potential added benefit of improving productivity in the sector, an aim outlined in the previous government’s food strategy.

Availability of technology

In 2022, Defra conducted an independent review into Automation in horticulture, where 6 key clusters of technologies were identified that could help accelerate the development and adoption of automation within horticulture (optimised production systems, packhouse automation, field rigs and mechanical systems, autonomous selective harvesting, augmented work and, autonomous crop protection, monitoring and forecasting). The first 3 of these are currently widely available for mass adoption within the sector. Overall, whilst they have the potential to increase worker productivity through reducing the ergonomic burden of tasks, in practice it was assessed that they offered minimal labour savings. The remaining 3 are currently in development pipelines with many at “prototype stages” and some devices currently undertaking farm trials. It is worth noting, this stage of development requires significant capital investment and therefore is often where new technology fails (if it is not sufficiently commercially viable to encourage large investments). The review also argues that many tasks within horticulture may never be automated. The limited availability of technology, and its adoption where available, is discussed more in Chapter 4.

There are barriers associated with adopting new technology as an alternative to labour. The Department for Business and Trade split these barriers into 3 categories: cost, certainty and capability which are discussed further below.

Certainty

For businesses to incur costs investing in technology that will have long-term benefits they require a level of certainty that the business will remain viable when the benefits are realised. Defra’s automation in horticulture review argues that the year-to-year confirmation of the SWS has acted as a disincentive to farmers to invest in automation. The first recommendation in the review, is that the SWS should be extended as it will incentivise long-term capital investments, including in automation technology. Automation in horticulture is still emerging and developing, and both availability of automated processes and their adoption at individual sites is likely to be piecemeal, with other parts of the process continuing to require labour.

However, as argued by Calvin et al., (2022), the access to (relatively) cheap labour allowed by the SWS could itself become a barrier to automation. If farmers are not certain they will have an adequate workforce, they are more likely to purchase machinery that will replace labour to reduce the risk of crops going unharvested, assuming such machinery exists. These outcomes are consistent with economy-wide results reported by Lewis (2011), who finds that firms in areas which experienced high inflows of less-skilled immigrant workers adopted significantly less machinery per unit of output, despite having similar adoption plans initially. Contrastingly, the certainty provided by extending the SWS may allow risk-averse farmers to refrain from investing in such technology until such a time that it is proven.

Capability

Technical and business knowledge across horticultural stakeholders varies significantly and hinders the adoption of new technologies. The skills required to develop, install, operate, and maintain the next generation of automation technologies will likely be science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) based. These are likely lacking within the horticulture sector, as traditionally they have not been needed.

Cost

The automation process in horticulture requires significant capital investment both in Research and Development (R&D) and in the equipment itself. Whilst this initial outlay can result in net benefit in the future, many farms argue they do not have sufficient capital to invest in new technologies. As an example of the costs involved, we were shown a packing plant at a large edible horticulture business that had three packing machines. Although the newest version was considerably more efficient, the business continued to use the older versions as replacing them would cost £250,000.

In addition, Defra’s review into Automation in horticulture argues it can be challenging to raise funds through external investors or grants, suggesting the technology is insufficiently advanced, and therefore carries unpalatable risk, discouraging investment. Whilst there is evidence of grants offering support these are often unsuitable for horticultural automation.

Whilst there are certainly challenges in increasing automation in agriculture, globally progress has been made. Israel and the Netherlands both provide potential case studies where there have been significant advancements in automating agricultural processes through investment in technology. This has led to prototypes becoming developed, with the potential to replace labour for much of the growing process. Some examples of technology currently in development include; software that enables one person to operate multiple vehicles performing various tasks from seeding to harvesting; flying robot fruit pickers which use AI to determine what is ripe and unblemished; robots with the ability to harvest, spray and pollinate indoor crops; and a system that automates the trellising of greenhouse vegetables.

Even though automation is clearly not a quick fix to replace seasonal workers, these examples provide evidence in the long term it may be a viable option to reduce the agricultural sector’s reliance on labour overall. Furthermore, it has the potential to improve productivity within the sector, helping to meet the aims of the previous government’s food strategy.

Individual farms would likely find it difficult to invest in the research and development of this technology due to the high risk and costs involved. Therefore, a top-down approach could be helpful where government promotes investments in these technologies. Currently there are 2 main policies relating to supporting agriculture investment (although their focus is wider than just automation): the Farming Investment Fund (FIF), and the Farming Innovation Programme (FIP). The FIF allows growers to purchase commercially ready technology at a reduced rate while the FIP is an R&D focused grant. Additionally, Defra made up to £12.5 million available for automation and robotics industrial research, and experimental development through their farming futures funding.

In future, intervention should be focused on the development of labour-saving technology where possible. This sentiment echoes the conclusions of the 2013 MAC report looking at seasonal work, and whilst technology has moved on as mentioned previously, the fact that 11 years on, the same recommendations are being made demonstrates the challenges associated with reducing reliance on labour in this sector. The previous government recognised the need for further automation in horticulture within their response to the Independent Review into labour shortages in the food supply chain where they stated their aim was to “turbo-charge” horticultural automation to help “transition away from low-skilled migrant labour as fast as possible”. Whilst this is a sensible ambition, limited information was provided as to how they planned on achieving this challenging goal.

Conclusion

Without the SWS, it is likely we would see a contraction in the domestic production of horticulture (and to a much lesser extent, poultry). Whilst this may not be massively detrimental to the UK economy due to agriculture’s relatively low economic contribution, it risks harming the nation’s food security in the future - the scheme is important if existing levels of domestic food production are to be maintained.

Advancements in automation may provide a possible alternative to migrant seasonal labour, however current machinery is not sufficiently developed to eliminate the need for seasonal work. Further intervention from government, such as 0% interest loans or increased public investment, could accelerate automation in this sector and in turn reduce reliance on seasonal labour.

Chapter 2: How the Seasonal Work Visa works

Summary

- The Seasonal Worker Visa (Temporary Work) allows workers to come to the UK to work in horticulture (both ornamental and edible) or poultry processing. The visa is delivered through the Seasonal Worker Scheme (SWS), which the Home Office and Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (Defra) are jointly responsible for.

- The government sets a quota for the number of visas to be allocated through the SWS, divided between a number of ‘scheme operators’ (7 for 2024 – 6 for horticulture and 2 for poultry, although 1 scheme operator licence was reportedly under review at the time of writing). For 2024, 47,000 visas were available (45,000 for horticulture and 2,000 for poultry, with an additional 10,000 available as a contingency if needed). Horticulture workers can come to the UK for a maximum of 6 months in any 12-month period, and poultry workers can come for the period between 2 October and 31 December inclusive. The route does not allow settlement, switching or dependants.

How the scheme is organised

Roles and responsibilities

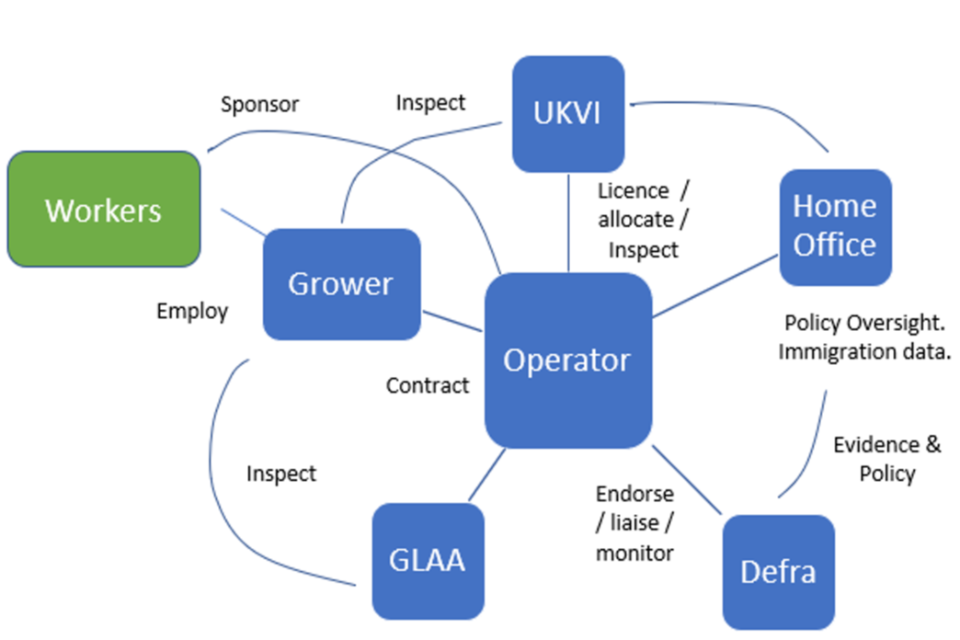

Reflecting their dual policy interest in the Seasonal Worker Visa (SWV), the Home Office and Defra are jointly responsible for delivering the route. The Home Office leads on immigration policy and operational delivery of the visa, while Defra selects, manages and monitors scheme operators, along with gathering stakeholder insights on the route. Compliance and enforcement responsibilities are discussed below and are shared between a number of different actors.

Sponsoring a Seasonal Worker

When recruiting Seasonal Workers in the UK, employers cannot recruit workers who are on the SWS directly (although they can recruit other types of worker, such as UK nationals, EU workers with settled status, and Ukrainians with permission to be in the UK). Employers must instead go through one of the nominated SWS scheme operators who act as the actual sponsors to the employee. 7 scheme operators were announced for 2024, 6 of which cover horticulture and 2 poultry, although 1 scheme operator licence was reportedly under review at the time of writing. As discussed in Chapter 1, the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS) in the UK that began in 1945 was initially envisaged as a type of cultural exchange programme, which over time became more formalised. Some of the initial SAWS labour providers became scheme operators, despite there being a gap of several years between the 2 schemes, and additional scheme operators have been added. Organisations wishing to become scheme operators first have to pass Defra’s Request for Information (RFI) process, which identifies potential operators through recruitment rounds and requires that they comply with the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) regulations. Once approved, they can begin applying for a licence and are referred to Home Office UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) to consider for licencing as an operator. 2 scheme operators also offer a payroll and HR package for SWS workers on behalf of each other to meet the requirement that organisations cannot recruit Seasonal Workers on their own behalf.

Scheme operators act as the brokers between employees and employers and are responsible for sourcing and recruiting Seasonal Workers from sending countries with permission from the relevant governments, which they may do either using their own staff or third-party recruitment agents.

Employers apply to scheme operators to request a specific number of Seasonal Workers for a given number of weeks and start date, and scheme operators balance recruitment with these requirements; consequently, scheme operators will tend to request booking numbers for a given calendar year by autumn of the previous year. Scheme operators use different charging models, for example a flat weekly rate or an upfront cost and lower weekly rate. Charges may also be made if the scheme operator accommodates and transports workers on the employer’s behalf.

Scheme operators are allocated a share of the overall Seasonal Worker quota (for 2024 most horticulture scheme operators received 7,500 each and 1,000 each for the 2 scheme operators recruiting for poultry), but in previous years this has varied. Operators entering the SWS for the first time will typically be given a smaller allocation. This represents their individual ceiling number of Certificates of Sponsorship (CoS) when the overall yearly quota is opened. The quota may be released incrementally, reflecting demand and operator performance. Once the scheme operators have identified the employees whom they wish to ‘sponsor’ to come to work in the UK, they assign a CoS to the worker and the worker uses this CoS to make their application online.

Workers may be given a CoS either for horticulture or poultry, but not both, even if the scheme operator has permission to recruit for both schemes. This is because the horticulture and poultry visas have different periods of validity (6 months for horticulture and around 3 months for poultry), and because there is some crossover between the roles available for poultry and the Skilled Worker (SW) route, with associated differences in salary requirements for some poultry production occupations.

Scheme capacity, withdrawn and expired visas

Following receipt of the CoS number from the scheme operator, the potential worker uses it to submit a visa application, at which point it counts towards the scheme operator’s quota. It must be used within 3 months of issuance in order to be accepted by UKVI. Should a CoS remain unused by the worker, scheme operators can reclaim it by withdrawing the CoS, and they will also have the CoS returned to their quota if the worker cancels it. Where one or more operators has confirmed that they are unlikely to meet their full individual allocation, these places can be redistributed to other operators, although this means that the number available in theory in the overall quota may also not be available in practice.

If a scheme operator has its licence suspended the workers are permitted to continue working. If a scheme operator has their licence revoked, workers in the UK have 60 days to find a new sponsor or alternatively return home. Those who are still in the visa approval process, having already paid their fee and submitted their application to UKVI, are unable to transfer to another operator and hence their applications are effectively cancelled. Workers who have not yet submitted their application may transfer to another scheme operator. After one of the scheme providers had its licence withdrawn in 2023, their visa quota was reallocated among the remaining scheme operators.

Since 2022 an additional quota of 10,000 has been available as a contingency in response to industry concerns about the adequacy of the overall cap and potential demand for Seasonal Workers, although this will cease in 2025. Any release of additional numbers would be made on condition that the 45,000 cap had been reached and in response to economic evidence of further recruitment need.

Nevertheless, as Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1 shows, the number of Seasonal Workers coming to the UK is well below the cap and the additional quota has never been used.

Internationally caps vary, as might be expected. New Zealand’s Recognised Seasonal Employers scheme, for example, has an annual cap which has previously been increased as needed due to employer demand, from an initial 5,000 when the scheme was established in 2007 to 19,500 for the 2023-24 season. It is set to balance employer need with the effects on the New Zealand labour market, expected labour market conditions in the coming year and the availability of suitable accommodation. The H-2A visa classification in the US, on the other hand, sets no limit on the number of workers that can be issued a visa to perform temporary work in the US.

Most CoS issued result in a worker coming to the UK. The refusal rate for 2023 was 2%, and the visa has had a refusal rate of <5% for every year since 2019 (individual operators must maintain a refusal rate of <5% to comply with sponsorship requirements). Only small numbers (<0.2% every year since 2018 aside from 2022) were withdrawn and none expired.

Rules of the scheme

Recruitment must be to specific roles, within the defined visa and cooling-off periods, and must comply with requirements on pay and hours worked. Accommodation may be charged for, subject to a maximum limit.

Visa time limit and ‘cooling off’ period

The Home Office’s Immigration Rules relating to Seasonal Workers set out that they may come to the UK for a maximum of 6 months in any 12-month period to work in eligible roles in edible or ornamental horticulture, or in poultry production from 2 October to 31 December each year. The worker’s visa is valid for whichever is the shorter of the period on the CoS, plus 14 days before and after, or 6 months in any 12-month period. Seasonal Workers may return to the UK in subsequent seasons but will only be issued a visa for 6 months in any 12-month period (the remaining 6 months is termed the ‘cooling off period’). These time limits are comparatively strict: for example, in New Zealand workers may stay for 7 months in any 11-month period (see Chapter 4 for further international comparisons). However, in reality, workers are often in the UK for less than the maximum length of their visa (as we discuss in Chapter 5).

There is no formal Home Office mechanism for requesting that the worker should return to the UK for subsequent seasons (the applicant simply makes a fresh application). However, in practice returnees are very important to scheme operators and employers (as we discuss in Chapter 4). Both scheme operators and employers often have systems to register workers’ interest in returning and employers’ interest in having the same worker back.

Roles recruited for

The Immigration Rules specify which job roles within edible and ornamental horticulture, and poultry production, are eligible for sponsorship on the scheme. Only certain roles within each SOC Code are eligible for the scheme. For employers using the horticultural scheme, demand for migrant labour support is highest in SOC Code 5112 (horticultural trades occupations), followed by 9111 (farm worker occupations). Of the roles eligible for the poultry scheme, the highest demand from employers is for workers in SOC Code 5433 (which covers poultry dresser occupations). Employers and representative bodies responding to our Call for Evidence (CfE) had used the SWS to recruit a wide range of roles (views on this are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4).

Pay, hours and accommodation

Costs

Workers are responsible for paying their own visa application and flight costs, and often onwards travel from the airport to their workplace if this is not provided by the employer. The cost of the SWV is currently £298, more than the £137 currently estimated as the unit cost for processing in Home Office visa fees transparency data. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) estimated the total cost for a Kyrgyz national to come to the UK to work on the SWS at between £914-£1,839 for 2022 in their response to our CfE [footnote 3].

Pay

Workers sponsored to work in the horticulture sector or in poultry production roles must be paid National Living Wage (NLW) (currently £11.44 per hour). For the poultry visa only, butchers (SOC 5431) or poultry dressers (SOC 5433) must be paid in line with SW thresholds (currently £15.88 per hour, or £38,700 per year pro rated). If the worker is being sponsored to work more than 48 hours a week, only the salary for the first 48 hours a week can be considered towards the £38,700 threshold.

Workers may be paid more than basic pay if they have supervisory responsibilities, night shifts, or enhanced picking/performance bonuses for exceeding targets. Overtime must be paid at the rate set out in the Agricultural Wages Guide. In the event that the relevant agricultural wage in one of the Devolved Nations exceeds the Seasonal Worker minimum wage as set out in sponsor guidance, employers must pay the higher wage. However, this has not happened to date.

Hours

Since 12 April 2023, the Immigration Rules have stated that Seasonal Workers must receive a minimum of 32 hours’ pay for each week of their stay in the UK, regardless of whether work is available. This change was made with the intention of ensuring that workers are not bearing significant risks from bad weather impacting availability of work.

Prior to this change, the minimum hours offered were set out as an aim (agreed with Defra and specified in the information given by operators in their Request for Information documents submitted as part of the bidding process) rather than a guarantee and varied between operators. In 2019, when the route was piloted, the minimum hours specified ranged from 20-30 hours pay per week and subsequent evaluation suggested that these were not always met. From 2020 onwards scheme operators continued to set out minimum hours on this non-guaranteed basis, and the Home Office was criticised by various Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) for not specifying a minimum number of weeks and not ensuring compliance with the hourly requirement, with workers describing having the hours they were offered cut when there was less work available.

Hours may be pro-rated over the pay period if workers are paid on a monthly or fortnightly basis rather than weekly. Workers must receive pay between placements where they are not employed by a single employer for the duration of their visa, and it is the scheme operator’s duty to ensure that any gaps in employment remain paid. This situation was recently clarified by the Home Office, prior to which scheme operators had interpreted the 32-hour per week requirement as applying only to the time workers were actually with producers on site. Table 2.1 shows that most workers responding to the 2022 Defra Seasonal Worker survey self-reported working for at least 32 hours on average. To note, this data was collected before the minimum hours guarantee, which applied from April 2023.

Seasonal Workers should not have to work more than 48 hours a week, including any overtime, unless by choice. They are entitled to at least 1 day off per week, or 2 days every two weeks, and a rest break of at least 20 minutes if working more than 6 hours per day.

Table 2.1: Self-reported hours worked per week (Defra Seasonal Worker Survey, 2022)

| What was the average number of hours you worked in a week? | % of responses: |

|---|---|

| Under 20 | 1% |

| 20-24 | 1% |

| 25-29 | 2% |

| 30-34 | 10% |

| 35-39 | 19% |

| 40-44 | 26% |

| 45-49 | 27% |

| Over 50 | 14% |

Source: Seasonal Worker Survey 2022. Base: All responding: 3,905.

Annual leave is based on normal working hours and accrues from the first day at work. When Seasonal Workers transfer or return to their home countries at the end of the visa, any annual leave accrued but not taken must be paid to them at their normal working rate.

Accommodation

Sponsor guidance requires scheme operators to ensure that “workers are housed in hygienic and safe accommodation that is in a good state of repair”. The Growers’ Toolkit lays out the responsibilities for growers: ensure appropriate licensing and registrations are in place; “letting agreements are professionally prepared, legal, clear, and fair”; and that “accommodation is secure, safe, hygienic and meets basic needs” avoiding conditions such as mould, dampness and overcrowding, in good repair and with safe gas/electric supply. Scheme operators are responsible for checking the standards of accommodation available before agreeing to place workers at a producer, most using standards such as those set out in the Fresh Produce Consortium guidance.

Employers can charge Seasonal Workers for accommodation, and most do so. Accommodation charges are capped at £69.93 per person per week, in line with the standard National Minimum Wage (NMW) and NLW accommodation offset rules. Employers can offset this against wages. Over and above accommodation, employers vary in what is included in the price – full or partial provision of gas/electricity, and whether or not items such as bedding, pans and plates are provided (in many cases workers have to buy these). Additional charges, such as utilities, laundry or furniture that workers are obliged to pay (as a precondition) must be included. If they are not then the accommodation charge must be decreased, workers’ base pay increased, or additional items not charged for.

The Low Pay Commission (LPC) has raised concerns about the interaction of the Seasonal Worker minimum wage rate and the accommodation offset charge in situations should the Seasonal Worker minimum wage rate be above NMW (as it was in 2022, when the Seasonal Worker rate of £10.10 per hour was higher than the NMW rate of £9.50; it is now set at NMW):

“In principle, an employer recruiting seasonal migrant workers and obliged to pay the higher rate, can allay the extra expense by increasing the accommodation charge they recoup from the workers. As long as workers receive an hourly rate of £10.10, the employer is compliant with the visa regime … the policy intent of the higher visa rate is undermined; the benefit to workers of higher hourly pay is removed.”

Pay is discussed further in Chapters 4 and 5 from both the employer and employee perspective.

Other rules of the scheme

Resident Labour Market Test

In common with other visa routes, there is no Resident Labour Market Test on the Seasonal Worker Route, although employers are nevertheless required to demonstrate that they are trying to recruit British workers (on a general and ongoing basis; they do not have to advertise each specific vacancy) to be eligible to use it. Other countries do use a form of resident labour market test. In Canada a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) is required before an employer can recruit seasonal workers. The LMIA must demonstrate that there are no available domestic workers and must be approved federally by the immigration department. The LMIA is not specific only to agriculture workers and is also a requirement for other sectors. Similarly, the US H-2A visa classification requires that there is not sufficient able, qualified, and willing US workers available for the job and the employment of a foreign worker in the job will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of US workers similarly employed in order for employers to be granted certification to employ workers with H-2A visas. As labour market tests delay recruitment, the requirement to demonstrate active efforts to recruit British workers therefore seems to be a pragmatic alternative. Employers’ efforts to recruit domestically are discussed further in Chapters 1 and 4.

Settlement and switching

The SWV is not a route to settlement, and switching is not allowed into other visa routes. Workers may also not switch onto the SWV if they are already in the UK on another visa.

English language

There is no English language requirement for the Seasonal Worker route, in common with other short- term work routes. However, in practice scheme providers may make other language rules – for example, that Seasonal Workers being recruited from Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) should be able to speak Russian, whether or not this is actually their first language. This is to facilitate informed recruitment and ensure the scheme provider is confident that people have understood the terms and conditions of the route before applying. There are pros and cons to such an approach from an employee welfare perspective, which are discussed in further detail in Chapter 5.

Dependants

Dependants are not permitted on the Seasonal Worker route. In practice, couples and family groups often come to the UK together, but on the basis that each adult has applied and been accepted separately (larger groups of family and friends might be subject to more detailed investigation by employers or scheme operators to check that there are no Modern Slavery concerns). Seasonal Workers can ask their scheme provider to place them with family and friends.

Financial requirements and access to public funds

People who are in the UK on the Seasonal Worker route have no recourse to public funds (NRPF). In common with other work routes, workers are required to demonstrate that they have personal savings of £1,270 in order to ensure that they can support themselves in the UK initially. The SWS allows scheme operators to act as a guarantor for a Seasonal Worker for their first month, thereby meeting this financial visa requirement. Often in practise they are happy to do this because they know the workers are going into employment. However, in some instances where employers are unaware of this requirement, they are often the ones to provide financial support when a worker arrives with insufficient funds. Chapters 4 and 5 discuss this requirement further.

Healthcare

People in the UK on the SWV have access to free primary and emergency healthcare only in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Other (secondary) treatment must be paid for, and as such Defra require scheme operators to have arrangements in place to ensure Seasonal Workers have adequate health insurance, or equivalent coverage, for medical expenses while they are in the UK. In Scotland, all NHS services (other than dental and eye care) that are free to UK citizens resident in Scotland are also free to Seasonal Workers.

Dismissal

Although employers must guarantee employment for the minimum number of hours and paid at the minimum rate, workers may still be dismissed for reasons including misconduct (for example fighting, possession of drugs) or poor performance. Workers may also choose to leave early – as we discuss in Chapter 4. Table 2.2 below shows that, while rates are fairly low, dismissal is far from unknown.

Discussions with employers indicated that before dismissing an individual, they may be tested in alternative roles on site first (for example moving from a picking to a packing role) but that if this proves unsuccessful, they may ask scheme providers to take the worker back. Scheme providers said that they would in these cases try the worker with another employer, but that if the worker was clearly unsuited to the work they may be dismissed altogether. Chapter 4 discusses retention in more detail, and Chapter 5 has additional information on early leaving: 75% of workers left as scheduled in 2022, with the remainder leaving early for a variety of reasons both voluntary and involuntary (see Figure 5.5).

Table 2.2: Dismissal rate (total workers)

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workers dismissed | 40 | 140 | 550 | 950 |

| Visas issued | 2,500 | 7,200 | 29,600 | 34,500 |

| Dismissal rates | 1.7% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 2.8% |

Source: Defra operator data, Home Office published immigration stats.

Note: Data from Q2 2019 – Q4 2022.

Transfers

Transfers may be requested by either Seasonal Workers or employers. Guidance states that there should be “a clear employer transfer pathway” and transfers should not normally be refused. Workers are able to request a transfer from scheme operators, and employers are unable to deny this if it is granted. Chapter 4 sets out that between 2020 and 2022 the overall transfer rate was 19%. Transfers are only possible between employers covered by the same scheme provider.