Seasonal workers pilot review 2019

Updated 16 July 2025

A joint Home Office and Defra review of the performance of the pilot in the first year of operation

Background

The horticulture sector in the UK has a long history of employing migrant workers to perform much of the seasonal work required to grow and harvest fruit and vegetables. From 1945 until 2013, the sector used schemes such as the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS) to bring in workers from a range of non-UK source countries.

From 2008 to 2013, the SAWS was closed to non-EEA nationals. Instead it was open only to nationals of Bulgaria and Romania while transitional limits on UK labour market access were applied to those countries, as part of their accession to the EU.

The SAWS closed at the end of 2013 when these limits for Bulgarian and Romanian agricultural workers were lifted, and growers were consequently no longer subject to restrictions on the number of workers they could recruit from those countries. The decision to end the SAWS was informed by advice from the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) which considered there to be no immediate shortfall in the supply of seasonal labour[footnote 1].

The MAC suggested that a shortfall might develop from 2017 onwards and later advised that a new scheme could be considered post-EU Exit[footnote 2].

Seasonal workers pilot

In March 2019 the UK government launched a new Seasonal Workers Pilot (Pilot), which allowed 2 licensed operators (Concordia and Pro-Force) to recruit up to 2,500 temporary migrant workers between them from non-EU countries to work in the UK edible horticulture sector for up to 6 months, in each of 2019 and 2020. Following the initial announcement, the scheme quota was subsequently expanded to 10,000 temporary migrant workers for 2020. Requirements to maintain high standards of immigration control and migrant welfare were essential to the new arrangements.

The 2 labour providers were selected to manage the Pilot through a fair and open competition process. The Request for Information (RFI) process set out the objectives of the Pilot, the minimum standards that the operators would need to meet, and the information that the Pilot operators would be required to provide to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Home Office during the course of its operation [footnote 3].

The 2 Pilot operators recruited and sponsored workers in 2019. As part of the criteria to be licensed by the Home Office, both operators were required to meet the Gangmaster’s and Labour Abuse Authority’s (GLAA) licensing and ethical labour standards requirements.

Review of the 2019 pilot

A joint Home Office and Defra review considered the performance of the Pilot in the first year of operation (in 2019). In preparation for the review, the government:

- identified the objectives and expected benefits against which the Pilot would be assessed

- developed a monitoring regime to collect the information required to review the Pilot against 9 stated objectives

- agreed a review process

Please note this review relates to the Pilot’s first year of operation in 2019. The Home Office and Defra will continue to monitor the Pilot for its duration.

Objectives and methodology

The 9 objectives of the 2019 Pilot, set out in section 6.3 of the RFI, were to:

- Determine if the Pilot could provide a longer-term model for responding to seasonal labour shortages in the horticulture sector.

- Test the Pilot’s ability to alleviate seasonal labour shortages in UK horticulture.

- Provide seasonal labour across the UK, so that all parts of the UK benefit from the Pilot.

- Assess the capability of the industry to manage the Pilot effectively.

- Assess the impact of the Pilot on local communities.

- Ensure that the Pilot provides for robust immigration control.

- Ensure that the Pilot adequately protects migrant workers from modern slavery and other labour abuses.

- Ensure that the monitoring and reporting regime adequately informs the government of the operation of the Pilot.

- Measure the financial impact of the Pilot.

Methodology

The review used both quantitative and qualitative data from government, operators, workers and industry, to assess whether the processes used to manage this Pilot proved effective. The following data sources were used:

- quarterly reporting by operators to Defra and Home Office (see Appendix 1)

- a survey of Pilot workers undertaken by Defra (see Appendix 3)

- Home Office compliance monitoring information (see Appendix 2)

- Home Office sponsorship management system (see Appendix 2)

- Home Office official statistics (see Appendix 2)

- GLAA compliance monitoring information (see Appendix 2)

The review was conducted by a joint team of Defra and Home Office policy officials, supported by economists and social researchers who advised on the analysis of the data. It considered whether the Pilot met its stated objectives, and if the delivery of the Pilot by the two labour providers was effective.

The analysis did not attempt an impact review and did not use any comparative data, such as how the Pilot compared with other models of seasonal labour provision.

Year one of the Pilot allowed a maximum of 2,500 workers, a small proportion of the total seasonal agricultural workers that come to the UK each year. The Pilot did not aim to meet all labour shortages in the sector, but to test an immigration route subcategory for seasonal workers.

Further detail on the methodology used in this report can be found in the appendices.

Objective 1: Determine if the Pilot could provide a longer-term model for responding to seasonal labour shortages in the horticulture sector

Collectively the operators successfully recruited and placed a total of 2,481 workers to UK farms against a maximum total of 2,500 workers permitted under the scheme.

Operators indicated that demand from both growers and potential workers was substantially higher than the 2,500 visas available – although operators previously indicated that some growers may have overbid, in the belief that this would increase the numbers of workers they eventually received.

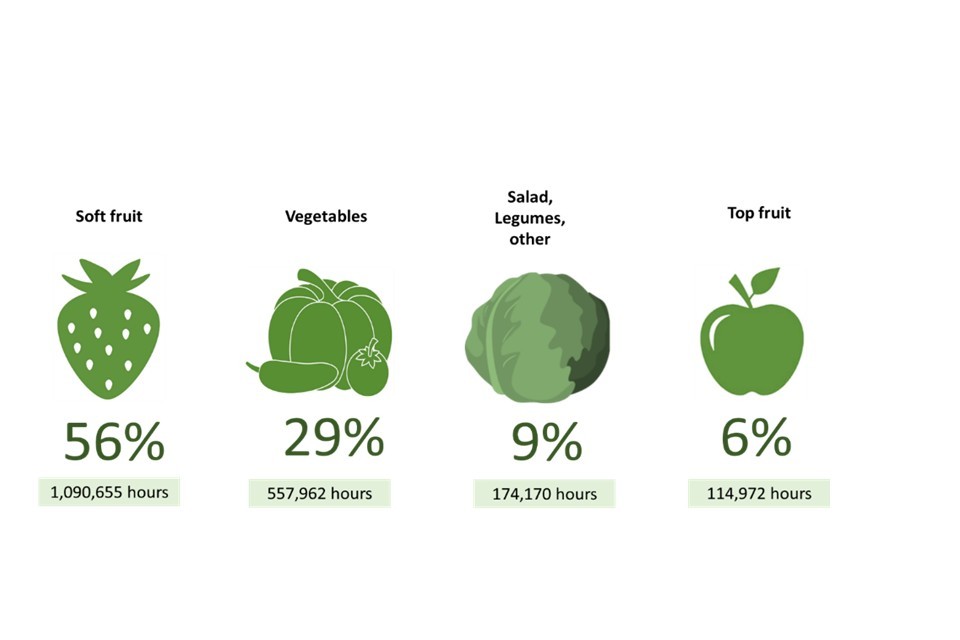

Pilot workers were spread across different crop types, offering labour to farms across the edible horticultural sector. The majority of total work hours were allocated to soft fruit, given its fragile nature and the need for it to be hand-picked.

Hours of work on 4 different crop types. The data is: Soft fruit: 1,090,655 hours (56%), Vegetables: 557,962 hours (29%), Salad, Legumes, Other: 174,170 hours (9%), Top fruit: 114,972 hours (6%).

68% of Pilot workers survey responses showed a desire to return to work on UK farms and 78% would recommend the UK to their friends or family as a place to work. These figures suggest a substantial level of interest among survey respondents in returning to work in the UK at some point.

Overall, available evidence indicated potential for the model to respond to seasonal horticulture labour shortages in 2019. The viability of the model was not assessed for the longer term and there are two main sources of uncertainty in the ability of a future Pilot to respond to seasonal horticulture labour shortages. Firstly, the supply of Pilot workers may not remain as high as the 2019 levels; a range of factors may impact the decisions of Pilot workers to work on UK farms, for example, rising wage rates in Pilot workers home countries. Secondly, further growth in the horticulture sector could increase demand for seasonal workers. The number of available Pilot workers may not be enough to satisfy increased levels of demand for this sector.

Objective 2: Test the Pilot’s ability to alleviate seasonal labour shortages in UK horticulture

The Pilot was not designed to meet the full labour needs of the edible horticulture industry. It was instead designed to test the effectiveness of the UK immigration system at supporting growers during peak production periods, and it has shown it can contribute towards that. 2,481 workers were supplied to UK farms, all of whom arrived on time and many of whom had relevant experience or expertise. The supply of labour was sustained across the 2019 season.

All workers arrived on time as defined in the Home Office sponsorship guidance of within 10 working days of their start date. Although this criterion was met, some farms reported a small number of workers arriving later than had been verbally agreed with Pilot operators. A high on time arrival rate assists in alleviating seasonal labour shortages, allowing farms to access workers when they are needed during peak production periods.

Of the workers who completed the survey of Pilot workers, 46% had previously undertaken seasonal work on a farm while 53% had not (1% unsure), demonstrating a moderate share of the survey sample had prior experience of work in the sector. In addition, anecdotal intelligence from the operators suggests that many workers were recruited from agricultural colleges and had relevant expertise.

The operators supplied a total of 2,481 workers to UK farms. Of the 2,545 visa applications received by the Home Office, 50 were withdrawn and one was refused. Some workers may not have made use of their visa, hence the number of workers supplied to farms is lower than the 2,494 visas granted.

Operators reported the farm businesses found Pilot workers of great use and almost all of the ~65 farms who participated in the Pilot applied for further Pilot workers in 2020. The dismissal rate for Pilot workers was low at <1%, indicating the Pilot’s ability to sustain labour supply across the season.

Operators indicated strong demand from workers in source countries for work on UK farms under the Pilot, indicating potential for further supply of workers under the Pilot to the sector, subject to workers meeting the scheme eligibility criteria.

Objective 3: Provide seasonal labour across the UK, so that all parts of the UK benefit from the Pilot

All regions of the UK had the opportunity to access seasonal labour through the Pilot. Operators were required to provide a reasonable distribution of workers across the UK, however no definition of ‘reasonable’ was specified.

Data from the quarterly reporting by Pilot operators showed 77% (1,905) of workers were placed in England, 23% (567) in Scotland and <1% in Northern Ireland. Once transfers of workers (where workers moved from their initial farm placement to another farm) between regions were accounted for, the estimated regional split remained broadly similar.

There were no requests for Pilot workers from Welsh farms, and Northern Ireland had low levels of demand for Pilot workers. This is due to small scale horticulture sectors in these regions. This indicates that the regional distribution of workers was in line with demand, although this cannot be concluded definitively without data on the exact level of demand in each country.

Poor weather in Scotland earlier in the 2019 season, with fields flooded and reduced demand for seasonal workers, resulted in 60 Pilot workers moving to English farms, highlighting operators’ response to labour needs to ensure workers had work.

Overall, the evidence shows that seasonal labour was provided across the UK, with the exception of Wales where no workers were requested. The distribution of labour was adapted as regional demand for workers changed over the course of the 2019 season. The regional allocation of workers will continue to be monitored as part of the extended Pilot review for 2020 to 2021.

Objective 4: Assess the capability of the industry to manage the Pilot effectively

Available evidence indicates improvements need to be made to the management of the Pilot, but that also industry effectively identified issues and took steps to resolve these. Effective management of the Pilot requires, among other things, that operators fulfil all the requirements placed on them, such as meeting immigration compliance requirements, ensuring that workers are treated well, and providing adequate reporting information to the government. Whilst many of the compliance visits to growers and farms were positive, some identified welfare issues, demonstrating there is clear room for improvement in this objective. The Home Office has reviewed the requirements placed on the scheme operators and updated the seasonal worker sponsor guidance[footnote 4] to tighten the compliance requirements. This is discussed further under objective 7.

The sponsor licensing model proved effective in identifying and licensing suitable organisations to manage the Pilot. The Pilot was operated in 2019 by two labour providers – Concordia and Pro-Force – who were selected in fair and open competition by Defra and licensed by the Home Office. The Pilot was new for the operators, as they were recruiting from outside the EEA. Defra’s role as an endorsing body proved effective in ensuring that the needs and working practices of the horticultural sector were reflected in the design of the Pilot and operator selection process. The model is transparent, with operators selected against clear, objective criteria published by Defra in their RFI.

The activities of both operators were overseen by the Home Office Compliance Network and the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA). The Home Office conducted 17 compliance visits to the two operators, and 15 farms of varying sizes and in different regions of the UK. 124 workers were interviewed, alongside other checks such as inspecting records and systems used to comply with sponsorship regulations. Six visits were conducted alongside the GLAA. Site visits by UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) compliance teams proved effective in identifying important issues, such as those referenced in objective 7.

The immigration compliance requirements placed on operators were met, as discussed in objective 6. All workers were paid at least the National Minimum Wage, and the majority of workers indicated that they were paid fully (84% of respondents) and on time (96%) in the survey of Pilot workers. We do not know the full circumstances of incidents where workers allege they were not paid fully or on time. 87% of survey respondents indicated that they were made aware of all terms and conditions of their placements before starting work, however the proportion claiming that operators adhered to contractual agreements was lower, at 71%. The Home Office have acted on this to ensure these figures improve, as discussed at the end of objective 7.

Another area for improvement, further to those discussed in objective 7, which was identified early in the Pilot, was the location of workers not being frequently updated on the Home Office system by the operators. This was resolved after UKVI reported their findings to the operators who improved their reporting.

Objective 5: Assess the impact of the Pilot on local communities

The assessment of this objective is inconclusive, due to limited available data to measure the impact on communities.

The 2,481 workers were spread across the UK and the number of workers in a specific community at any one time was unlikely to have any significant impact. A larger proportion of Pilot workers were provided to farms in the South East of England, East Anglia, and East Scotland, however the number of workers in these communities were still low overall.

Data from the quarterly reporting by the operators indicates around 89% of Pilot workers were accommodated on-site on farms, limiting pressure on local housing supply[footnote 5]. Pilot workers made limited use of local healthcare services, with 3 GP and 1 hospital visit per 100 workers. This may in part be due to their age, which averaged 27, and the lower likelihood of poor health in younger people. We do not have information on the nature of these visits, so we cannot conclude whether or not they were related to work.

Pilot workers were not allowed to bring any family members with them under the conditions of the visa, so there was no impact on children’s schools. However, workers could take up study alongside their work. We do not have the data to assess the levels of take up for this.

Any other wider impacts of seasonal workers on local communities were not assessed within this review.

Objective 6: Ensure that the Pilot provides for robust immigration control

The Pilot proved compliant with the immigration system based on data discussed below.

Home Office data show that the visa approval requirement of 90% (no more than 10% of Pilot workers sponsored by operators are refused their visa by UKVI) for the Pilot was fully met. Only one Pilot worker selected by the operators was refused a visa. This requirement was placed on the operators to ensure they were recruiting suitable workers under the Pilot.

The requirement for 95% of workers to depart the UK on time was also met and surpassed, with more than 99% of Pilot workers leaving at the end of their visa (one worker’s whereabouts is unknown). These figures showed the selection of workers by the operators worked effectively from a migration security perspective.

Further immigration control measures were added to the Pilot for 2020, including tightening the requirements described above to 95% and 97% respectively. This sought to ensure the scheme maintains and builds on the standards achieved in year one.

Objective 7: Ensure that the Pilot adequately protects migrant workers from modern slavery and other labour abuses

While no instances of modern slavery were identified, some examples of other alleged welfare issues were reported to the Home Office during compliance visits, within Defra’s survey of Pilot workers, and by operators. The Pilot sought to protect workers from modern slavery and other labour abuses. The government places great importance in upholding migrant welfare, given they may be more vulnerable and open to exploitation than other workers. Oversight was provided by the Home Office and GLAA. Some further data was gathered by Defra’s survey of Pilot workers.

As referenced under Objective 4, the Home Office conducted 17 compliance visits, six of which were conducted alongside the GLAA. 5% of all migrant workers (124 workers) were interviewed, and visits were targeted to ensure growers of different sizes and in different regions of the UK were visited.

Almost half the compliance visits identified workers who had not received their employment contract in their native language, which was a requirement for the Pilot. Migrants interviewed at four sites also alleged that their employers had not provided promised health and safety equipment as they were legally required to do, specifically wet weather gear and steel toe capped boots, leaving some workers to source their own. Both points were raised with the Pilot operators to remedy, and policy officials have followed this up in further discussions with operators. Operators are not permitted to work with farms that do not comply with our scheme criteria.

Data from the quarterly reporting by the operators shows a complaint rate from all workers of 1% was recorded by operators across the first year of the Pilot, with a follow-up rate of 80% by the operators to address any issues formally. Operators reported that complaints ranged from informal discussions with farm managers to formal complaints to operators. Workers, if they wished, could bypass their farm manager, and speak directly to their operator using a helpline, the details of which were provided to workers in their introductory pack. We do not have data on how many workers used this method to make a complaint.

Although all of the aforementioned complaints were addressed, a small number were addressed through informal procedures - which the monitoring template did not record. The monitoring template for the 2020 Pilot was amended to capture information on complaints addressed through informal procedures.

The GLAA also licenses the operators and monitors their activity. No licensing issues were reported.

Data available from quarterly reporting by Pilot operators shows all Pilot workers were paid rates in line with UK legislation, with all workers paid at least the National Minimum Wage. Average wage data in all quarters was also above the national minimum wage for over 25 year olds. Across the year, Pilot workers earned an average of £8.77 per hour. The minimum wage from April 2019 was £8.21 for over 25s.

Defra’s survey of Pilot workers identified several areas for improvement. A number of respondents to the survey of Pilot workers reported issues with the quality of accommodation (15% said their accommodation was neither safe, comfortable, hygienic nor warm and 10% said their accommodation had no bathroom, no running water, and no kitchen). The Home Office and the GLAA did not identify any issues during site visits, however, we have raised this with operators to make sure accommodation consistently meets the correct standard in the future.

Separately, operators identified that recruitment presentations to potential worker applicants for the Pilot did not always accurately reflect the accommodation available, which created inaccurate expectations among workers. Both operators improved their recruitment presentations to make the accommodation offered clearer and committed to act on any complaints reported to them on accommodation standards.

The worker survey also identified that 22% of respondents alleged they were not treated fairly by farm managers. Farm managers have not been given an opportunity to respond to these allegations. Responses reported racism, discrimination, or mistreatment by managers allegedly on grounds of workers’ nationality by being subject to disrespectful language or passed over for better work or accommodation. The operators acknowledged that any behaviour of this kind is unacceptable.

Both operators increased training for managers in 2020, alongside existing support routes for migrant workers such as check in calls and group social media chats with agents to report concerns, formal complaint processes, and discrimination training for recruiters. Discrimination and racism were reported to compliance officers at one site visit and the Home Office received a similar report from a member of the public. Both were reported to the GLAA and to the relevant operator, which took remedial action with the employer.

Although the Pilot met part of this objective, as no instances of modern slavery was identified, other alleged welfare issues identified are unacceptable. The Home Office has reviewed the requirements placed on the scheme operators and updated the seasonal worker sponsor guidance to tighten the compliance requirements. The Home Office has worked with the scheme operators to ensure these requirements are fully embedded.

Objective 8: Ensure that the monitoring and reporting regime adequately informs the government of the operation of the Pilot

The monitoring system for the Pilot was designed to enable the government to assess the Pilot and effectively respond to in-year developments. The system worked well to inform the government about successful aspects of the Pilot and what could be improved, as well as enabling it to respond quickly to developments during the first year of the Pilot.

The sponsor licensing regime provided a responsive and flexible mechanism for both monitoring scheme performance, and for rapidly adjusting quotas and criteria as necessary. For example, the change made in the sponsor guidance to the compliance requirements placed on operators (for example, the visa approval requirement of 90% was increased to 95% ahead of 2020, for that year of the Pilot).

The quarterly reporting to Defra and Home Office by operators provided early insight into trends and potential issues and all compliance visits to farms showed adequate migrant monitoring and reporting systems were in place. Some amendments were made for year two to increase the detail of the data collected, for example on the reasons for early departures.

The end of year survey of migrant workers provided further data and was repeated for 2020 based on its effectiveness in 2019. The Home Office and Defra are looking at ways to improve the response rate (26%) and ensure a more representative source of data for future reviews of the Pilot.

Objective 9: Measure the financial impact of the Pilot

The evidence to measure the financial impact of the Pilot was limited, however as discussed below, available data indicates the Pilot had a neutral financial impact.

Data available from the quarterly reports by operators provided insight into the fiscal impact and the impact on Home Office income and expenditure.

Fiscal impact

Seasonal agricultural workers have an impact on tax revenue and spending on public services, which has implications for overall fiscal balance. There are a number of different approaches to calculating the effect of migration on fiscal balances. Using an alternative approach may lead to higher or lower estimates than the fiscal impacts set out below. Moreover, this approach does not attempt the counterfactual – such as fiscal impacts in the absence of the scheme.

Data on national insurance contributions were provided directly by operators which reported that seasonal workers paid approximately £1 million in 2019. Whilst tax receipts were reported, based on wage rates provided by operators and the temporary nature of each worker’s time in the UK, it is assumed that no migrants earned above the £12,500 threshold for income tax.

The overall impact on the Exchequer would also include contributions to other receipts and costs, such as council tax for migrants accommodated off-site and indirect taxes which include consumption, corporation taxes and business rates. The net impact should also take into account:

a) the value of public services consumed by considering components such as spend on health, social services and sickness.

b) wider public services, which when consumed have reduced availability to others.

These costs and benefits were not collected and estimated as part of the review, but the Home Office methodology for estimating fiscal impacts[footnote 6] would predict that the overall net fiscal impact of seasonal workers would be positive, but likely to be very small (<£1 million). The fiscal impact model used by the Home Office predicts low use of public services because seasonal workers were relatively young, on average aged 27 years, and without dependants. The estimates are based on average use by the general population, so do not take account of actual use of public services by migrants or any differences between occupations. Though limited, the quarterly monitoring data provided by operators also indicates low usage of GP and hospital services.

While Home Office methodology would suggest a small positive net fiscal impact of the Pilot, this is not guaranteed for future operations involving seasonal workers. Fiscal estimates are highly uncertain and change over time, while revenues and costs are likely to scale very differently if the size of the scheme changes in the future.

Home Office income and expenditure

The Pilot was relatively expensive for the Home Office to operate compared to other sponsorship routes the Home Office operates, particularly the compliance and monitoring activities. Compliance monitoring in rural environments involved greater travel distances to disparate remote locations and larger visit teams. The need to source suitable translators – not typically required in most immigration routes due to English language requirements - also increased costs. Other costs incurred to the Home Office included visa and Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) processing costs.

The Home Office was able to cover these costs through revenue from visa and CoS fees. This does not necessarily mean that the Home Office would break even in future operation of the Pilot as the net impact will ultimately depend on how costs scale as numbers of workers recruited increase.

The cost of the Pilot to parties other than the Home Office was not assessed.

Next steps

The government continues to assess the Pilot for 2020 and 2021, giving us more evidence to consider. The expansion of the Pilot to 10,000 places in 2020, and 30,000 in 2021, offers the opportunity to measure its ability to recruit and manage a larger volume of workers, taking the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) into account.

This review for 2019 has shown positive aspects of the Pilot as well as some clear areas for improvement, particularly with concern to migrant welfare, which (as discussed at the end of objective 7) the Home Office has already taken steps to address. These issues will be closely monitored in the ongoing delivery of the Pilot.

The next review will assess the Pilot in both 2020 and 2021. The assessment will modify the objectives from those used in this report to take account of progress in the original Pilot objectives since 2019, to reflect our findings in this report and the UK’s departure from the EU. This will be compiled into 4 themes: monitoring; operations; immigration compliance and migrant welfare.

The Home Office and Defra will work closely with other government departments including the Department for Work and Pensions and Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, as well as relevant stakeholder groups, to broaden the objectives for the extended Pilot review for 2020 and 2021.

The Home Office and Defra will also look at the economic impacts of the Pilot. Assessing the effectiveness of the Pilot at addressing the sector’s seasonal labour shortages, identifying any unintended impacts of the scheme, and considering how alternative solutions to labour shortages could reduce reliance on migrant workers over time.

As part of this, there will be a key focus on how the sector could increase the use of farm technology and encourage UK domestic workers into these seasonal horticultural roles, including developing sustainable careers for workers in this sector.

-

Workers and Temporary Workers: guidance for sponsors: sponsor a seasonal worker. ↩

-

Figure estimated from a weighted average of total workers in the UK during each quarter. ↩

-

Technical paper to accompany impact assessment for Immigration and Social Security Co-ordination (EU Withdrawal) Bill 2020. ↩