Serious and Organised Crime Strategy (accessible version)

Published 1 November 2018

Serious and Organised Crime Strategy

November 2018

Cm 9718

Serious and Organised Crime Strategy Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for the Home Department by Command of Her Majesty

Foreword by the Home Secretary

Serious and organised crime is the most deadly national security threat faced by the UK, and persistently erodes our economy and our communities. Serious and organised criminals operating in the UK sexually exploit children and ruthlessly target the most vulnerable, ruining lives and blighting communities. Their activities cost us at least £37 billion each year. They are able to reap the benefits of their crimes and to fund lavish lifestyles while all of us, and particularly their direct victims, suffer the consequences.

Protecting the public is my highest priority as Home Secretary. This strategy sets out the government’s approach to prevent and defend against serious and organised crime in all its forms, and our unyielding endeavour to track down perpetrators, from child sex offenders to corrupt elites, to bring them to justice. We will allow no safe space for these people, their networks or their illicit money in our society.

Following the publication of the previous Serious and Organised Crime Strategy in 2013, we have made significant progress in creating the powers, partnerships and law enforcement structures we need to respond to the threat. The law enforcement community, and the National Crime Agency in particular, has been instrumental to this progress with an impressive, and sustained, track record of disruptions across the full range of serious and organised crime threats.

Despite all of our success, we must continue to adapt to the scale and complexity of current and future threats. The individuals and networks involved in serious and organised crime are amongst the most capable and resilient adversaries that the UK faces. They are quick to exploit the rate of technological change and the globalisation of our society, whether it is live streaming of abuse or grooming children online, using malware to steal personal data, or exploiting free and open global trade to move illegal goods, people and money across our borders.

The threat transcends borders, and serious and organised crime in the UK is one part of a global web of criminality. Child sex offenders share images of abuse on a global basis. There is a direct link between the drugs being sold on our streets, including the violence linked to that trade, the networks trafficking vulnerable children and adults into the UK, the corrupt accountant laundering criminal funds through shell companies overseas, and corrupt politicians and state officials overseas who provide services and safe haven for international criminal networks.

Our revised approach puts greater focus on the most dangerous offenders and the highest harm networks. Denying perpetrators the opportunity to do harm and going after criminal finances and assets will be key to this. We will work with the public, businesses and communities to help stop them from being targeted by criminals and support those who are. We will intervene early with those who are at risk of being drawn into a life of crime. And, for the first time, this strategy sets out how we will align our efforts to tackle serious and organised crime as one cohesive system. This includes working closely with international partners as well as those in the private and voluntary sectors.

Serious and organised criminals may often think they are free to act with impunity against our children, our businesses and our way of life. They are wrong. They believe that they can use violence, intimidation and coercion to stay above the law, and that the authorities lack the necessary tools and will to take them on. Working together, implementing this new strategy, we will show them just how wrong they are.

Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP

Home Secretary

Executive Summary

1. Serious and organised crime affects more UK citizens, more often, than any other national security threat and leads to more deaths in the UK each year than all other national security threats combined.[footnote 1] It costs the UK at least £37 billion annually.[footnote 2] It has a corrosive impact on our public services, communities, reputation and way of life. Crime is now lower than it was in 2010,[footnote 3] although we are also aware that since 2014 there have been genuine increases in some low volume, high harm offences. The National Crime Agency (NCA) assesses that the threat from serious and organised crime is increasing and serious and organised criminals are continually looking for ways to sexually or otherwise exploit new victims and novel methods to make money, particularly online.

2. A large amount of serious and organised crime remains hidden or underreported, meaning the true scale is likely to be greater than we currently know. Although the impact may often be difficult to see, the threat is real and occurs every day all around us. Serious and organised criminals prey on the most vulnerable in society, including young children, and their abuse can have a devastating, life-long effect on their victims. They target members of the public to defraud, manipulate and exploit them, sell them deadly substances and steal their personal data in ruthless pursuit of profit. They use intimidation to create fear within our communities and to undermine the legitimacy of the state. Enabled by their lawyers and accountants, corrupt elites and criminals set up fake companies to help them to hide their profits, fund lavish lifestyles and invest in further criminality.

3. Serious and organised crime knows no borders, and many offenders operate as part of large networks spanning multiple countries. Technological change allows criminals to share indecent images of children, sell drugs and hack into national infrastructure more easily from all around the world, while communicating more quickly and securely through encrypted phones. Continuously evolving technology has meant that exploitation of children online is becoming easier and more extreme, from live-streaming of abuse to grooming through social media and other sites. Serious and organised criminals also exploit vulnerabilities in the increasing number of global trade and transport routes to smuggle drugs, firearms and people. They have learnt to become more adaptable, resilient and networked. Some think of themselves as untouchable.

4. In some countries overseas, criminals have created safe havens where serious and organised crime, corruption and the state are interlinked and self-serving. This creates instability and undermines the reach of the law, hindering our ability to protect ourselves from other national security threats such as terrorism and hostile state activity. Corruption, in particular, hinders the UK’s ability to help the world’s poorest people, reduce poverty and promote global prosperity.

Our response

5. Despite significant progress, the scale of the challenge we face is stark and we have therefore revised our approach. Our aim is to protect our citizens and our prosperity by leaving no safe space for serious and organised criminals to operate against us within the UK and overseas, online and offline. This strategy sets out how we will mobilise the full force of the state, aligning our collective efforts to target and disrupt serious and organised criminals. We will equip the whole of government, the private sector, communities and individual citizens to play their part in a single collective endeavour to rid our society of the harms of serious and organised crime, whether they be child sexual exploitation and abuse, the harm caused by drugs and firearms, or the day to day corrosive effects on communities across the country. We will pursue offenders through prosecution and disruption, bringing all of our collective powers and tools to bear. We will: prevent people from engaging in serious and organised crime; protect victims, organisations and systems from its harms; and prepare for when it occurs, mitigating the impact. We will strengthen our global reach to confront the threat before it comes to our shores.

6. This strategy provides a framework and outlines a set of capabilities which are designed to respond to the full range of serious and organised crime threats. We have four overarching objectives to achieve our aim:

- 1. Relentless disruption and targeted action against the highest harm serious and organised criminals and networks We will target our capabilities on criminals exploiting vulnerable people, including the most determined and prolific child sex offenders and we will proactively target, pursue and dismantle the highest harm networks affecting the UK. We will use new and improved powers and capabilities to identify, freeze, seize or otherwise deny criminals access to their finances, assets and infrastructure, at home and overseas including Unexplained Wealth Orders and Serious Crime Prevention Orders. At the heart of this approach will be new data, intelligence and assessment capabilities which will allow the government, in particular the NCA, to penetrate and better understand serious and organised criminals and their vulnerabilities more effectively and target our disruptions to greater effect.

- 2. Building the highest levels of defence and resilience in vulnerable people, communities, businesses and systems We will remove vulnerabilities in our systems and organisations, giving criminals fewer opportunities to target and exploit. We will ensure our citizens better recognise the techniques of criminals and take steps to protect themselves. This includes working to build strong communities that are better prepared for and more resilient to the threat, and less tolerant of illegal activity. We will also identify those who are harmed faster and support them to a consistently high standard.

- 3. Stopping the problem at source, identifying and supporting those at risk of engaging in criminality We will develop and use preventative methods and education to divert more young people from a life of serious and organised crime and reduce reoffending. We will use the government’s full reach overseas to tackle the drivers of serious and organised crime.

- 4. Establishing a single, whole-system approach At the local, regional, national and international levels, we will align our collective efforts to respond as a single system. We will improve governance, tasking and coordination to ensure our response brings all our levers and tools to bear effectively against the highest harm criminals and networks. We will expand our global reach and influence, increasing our overseas network of experts to ensure the UK’s political, security, law enforcement, diplomatic, development, defence relationships and financial levers are used in a more coordinated and intensive manner. And we will work to integrate with the private sector, pooling our skills, expertise and collective resources, co-designing new joint capabilities, and designing out vulnerabilities together.

7. As a result, we will be able to measure and demonstrate that:

a) We have significantly raised the risk of operating for the highest harm criminals and networks within the UK and overseas, online and offline, by ensuring:

- new data and intelligence capabilities have targeted and disrupted serious and organised criminals and networks in new ways;

- a range of partnerships and working practices are embedded in the UK that enable us to sharpen and accelerate our response;

- overseas partners are working with us more often, more collaboratively and more effectively to target serious and organised crime affecting the UK; and

- we are arresting and prosecuting the key serious and organised criminals, stopping their abuse, denying and recovering from them their money and assets, dismantling their networks and breaking their business model.

b) Communities, individuals and organisations are reporting they are better protected and better able to protect themselves; and victims are better supported to recover from their abuse or exploitation.

c) Fewer young people are engaging in criminal activity or reoffending.

Introduction

8. The strategy builds on the 2015 National Security Strategy (NSS) and Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR),[footnote 4] which identified serious and organised crime as a national security threat. It also reflects the findings and recommendations of the 2018 National Security Capability Review (NSCR).

9. This strategy has links to other government strategies, including the UK’s Strategy for Countering Terrorism (CONTEST),[footnote 5] the UK Anti-Corruption strategy 2017-2022,[footnote 6] the National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS) 2016-2021[footnote 7] and the Modern Slavery Strategy 2014.[footnote 8] It also links to the government’s work on serious violence, particularly for threats such as county lines and firearms offences. We set out the links between this strategy and the 2018 Serious Violence Strategy[footnote 9] throughout both documents.

10. The Home Secretary has responsibility for the Serious and Organised Crime (SOC) Strategy, but this is a cross-government strategy. The Home Office has led work to produce the strategy, with major contributions from other government departments and agencies, and in close partnership with the devolved administrations, local police forces and the private sector. A new Director General within the Home Office was appointed in 2018 to oversee the response to serious and organised crime.

11. The devolved administrations in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales are responsible for the functions which have been devolved to them. In Scotland and Northern Ireland, crime and policing matters are the responsibility of the Scottish Government and the Northern Ireland Executive. These devolved administrations have published their own respective strategies (Scotland’s Serious Organised Crime Strategy 2015[footnote 10] and Northern Ireland’s Organised Crime Strategy 2016).[footnote 11], [footnote 12] In Wales, we will continue to work very closely with the Welsh Government and the four Welsh Police and Crime Commissioners to implement the ambition of this strategy.

12. Part One of this document sets out the current threat. This includes defining what we mean by serious and organised crime, summarising its impact and setting out how it is likely to evolve.

13. Part Two covers our new strategic approach and sets out our overall ambition in responding to serious and organised crime.

14. Part Three focuses on how this translates into action around our four overarching objectives.

15. Part Four describes how we will implement the strategy in the UK and overseas, including details on governance and oversight and how we will measure our effect.

Part One: The Impact of Serious and Organised Crime on the UK

16. We define serious and organised crime as individuals planning, coordinating and committing serious offences, whether individually, in groups and/or as part of transnational networks. The main categories of serious offences covered by the term are: child sexual exploitation and abuse; illegal drugs; illegal firearms; fraud; money laundering and other economic crime; bribery and corruption; organised immigration crime; modern slavery and human trafficking; and cyber crime.

17. Crime is now lower than it was in 2010. Our best measure of long-term crime trends on a consistent basis, the Crime Survey of England and Wales,[footnote 13] shows a 34% fall in comparable crime over this period. But we are also aware that since 2014 there have been genuine increases in low-volume, high harm offences like knife crime, gun crime and homicide.

18. The National Strategic Assessment of Serious and Organised Crime, published annually by the NCA sets out the threat in detail.[footnote 14] In 2018, the NCA is aware of over 4,600 organised crime groups operating in the UK.[footnote 15] Yet, much serious and organised crime remains hidden (child sexual exploitation and abuse, modern slavery), or underreported (fraud, cyber crime), meaning the true scale is difficult to measure and likely to be much greater. Figure 1 outlines some of the indicators of the scale and scope of serious and organised crime threats.

Figure 1 – NCA assessment of serious and organised crime threats to the UK

Vulnerabilities:

- 35% increase in potential modern slavery & human trafficking victims referred to National Referral Mechanism in 2017

- organised immigration crime

- organised immigration crime

Prosperity:

- bribery, corruption and sanctions evasion

- there is a realistic possibility the scale of money laundering impacting the UK annually is in the tens of billions of pounds

- 3.3 million fraud incidents in England & Wales (year ending June 2018)

- 43% of UK businesses identified at least one cyber security breach or attack in 2017

Commodities:

- 2,503 deaths from drug abuse in England & Wales in 2017

- 25% increase in firearm offences between 2015/16 and 2017/18

19. We estimate serious and organised crime costs the UK at least £37 billion annually.[footnote 16] This figure has increased by £13 billion since the 2013 estimate, although this is in large part attributable to changes in methodology to produce more robust estimates, and the inclusion of additional crime types (such as organised waste crime and organised cyber-dependent crime against individuals).

20. Demand for common drug types remains high in the UK, with around 1.1 million adults having taken a Class A drug in 2017/18.[footnote 17] There were 2,503 drug misuse deaths registered in England and in Wales in 2017; heroin and/or morphine remained the most lethal drugs, responsible for 47% of these deaths.[footnote 18] Recent trends include a spike in the availability of highly toxic synthetics, notably Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid up to one hundred times more potent than morphine and linked to multiple heroin-associated deaths nationally in 2017.[footnote 19]

21. There has also been an increase in the availability[footnote 20] of crack cocaine and an increase in its use[footnote 21]. The street-level purity of crack increased from 36% in 2013 to 71% in 2016, indicating a fluid supply-line capable of overcoming short-term shocks. As set out in the Serious Violence Strategy, there is evidence that crack cocaine markets have strong links to serious violence and there is a connection between recent increases in homicide and knife and gun crime, and rising levels of the use and purity of crack cocaine. Research suggests heroin and crack cocaine users commit around 45% of all theft offences in England and in Wales. More broadly, the groups involved in so-called county lines drug distribution networks are impacting on all police force areas and causing significant harm, including violence, firearms use and exploitation of young and vulnerable people.

22. Serious and organised crime has a devastating effect. Any child can be a victim of abuse or exploitation and criminals are exploiting the huge growth in numbers of children with easy access to the internet. The stereotypes of the ‘typical’ child exploitation victim are further than ever from the truth. The exploitation of children online is becoming easier and more extreme.[footnote 22] All ages are affected, from babies and toddlers through to older teenagers. Child sex offenders are becoming more sophisticated, using social media, image and file sharing sites, gaming sites and dating sites to groom potential victims. In response to law enforcement efforts to apprehend them, they are using encryption, anonymisation and destruction measures on the dark web and the open internet. Live-streamed abuse is a growing threat and children’s own use of self-broadcast live-streaming applications are being exploited by offenders.

23. The number of referrals to the NCA relating to online child sexual exploitation and abuse has increased by 700% in the last four years.[footnote 23] The most immediate impact of exploitation and abuse of vulnerable people is physical and emotional harm to the individual, and the many thousands of victims each year are left with long-term needs which can also have an enduring impact on public services. Organised exploitation on a large scale, such as that seen in Rotherham and elsewhere has also caused generational damage to the integrity and cohesion of local communities. Serious and organised criminals prey on the most vulnerable people in our society, and those who are economically disadvantaged or who are displaced from their home or country are particularly vulnerable to exploitation.[footnote 24] 5,145 potential victims of modern slavery and human trafficking were referred to the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) in 2017, a 35% increase on 2016. The number of children referred to the NRM increased by 66% over this period.[footnote 25]

24. Communities also feel the impact of serious and organised crime through the violence and intimidation that often accompanies many types of crime.[footnote 26] Organised criminals can drive out legitimate businesses and use firearms to protect or further their criminal enterprises. There was a 25% increase in firearms offences between 2015/16 and 2017/18.[footnote 27] There is also a risk that terrorists may attempt to procure firearms through criminal networks.

25. Economic crime is a broad category of illegal activity, including fraud, corruption, money laundering, and tax evasion. There were 3.3 million fraud incidents in the year ending June 2018, amounting to almost a third of all crimes.[footnote 28] The overall scale of economic crime is estimated to be £14.4 billion per year, with the cost to businesses and the public sector from organised fraud no less than £5.9 billion per year.[footnote 29] For the purposes of this strategy, illicit finance involves the holding, movement, concealment or use of monetary proceeds of crime that has an impact on UK interests. Organised crime groups and corrupt elites launder the proceeds of crime through the UK to fund lavish lifestyles and reinvest in criminality. The vast majority of financial transactions through and within the UK are entirely legitimate, but its role as a global financial centre and the world’s largest centre for cross-border banking makes the UK vulnerable to money laundering. There is a realistic possibility that the scale of money laundering impacting the UK annually is in the tens of billions of pounds. This presents significant reputational risk to the integrity of the UK’s financial sector, which is essential for global trade and our long-term prosperity. Professionals such as lawyers and accountants are an important part of the response to serious and organised crime. However, whether complicit, negligent or unwitting, professional enablers are also key facilitators in the money laundering process and often crucial in integrating illicit funds into the UK and global banking systems.[footnote 30]

26. Cyber attacks from criminals continue to damage the economy, and cyber security breaches are a costly and disruptive issue for businesses. 43% of all UK businesses identified at least one cyber security breach or attack in 2017, a figure which rose to 64% among medium size firms and 72% for large firms.[footnote 31] High profile attacks such as the WannaCry ransomware campaign, which disrupted over a third of NHS trusts in England and led to thousands of operations being postponed, emphasise the real world harms resulting from these attacks. The distinction between nation states and criminal groups in terms of cyber crime is becoming frequently more blurred, making attribution of cyber attacks increasingly difficult.

27. Corruption threatens our national security and prosperity, at home and overseas. Domestically there is a particular risk to the borders and immigration, law enforcement and prison sectors which can undermine the rule of law, while overseas it is a cause of conflict and instability which, if not tackled, can increase risks to the UK. Organised criminality, corruption and kleptocracy are also increasingly severe impediments to the UK’s overseas policy and development objectives. They distort and impede inclusive and sustainable economic growth, corrupt the democratic process, threaten legitimate, sustainable livelihoods, damage social cohesion and exacerbate exclusion. All of these factors challenge the UK’s ability to help the world’s poorest people, reduce poverty and promote global prosperity.

How serious and organised crime is likely to evolve

28. Serious and organised crime is increasing both in volume and complexity.[footnote 32] According to the NCA, advances in technology and instability caused by international conflict in particular will offer criminal networks new ways to identify and target victims and find new markets and ways to make money.

Technology

29. Advances in technology will continue to transform the future of crime. Rapid development of new information and communication technologies (especially the introduction of 5G mobile communications, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things) is likely to present opportunities for criminal exploitation. The use of technologies such as the Dark Web, encryption, virtual private networks and virtual currencies (such as Bitcoin) will support fast, ‘secure’ and anonymous operating environments that facilitate all levels of criminality. The increasingly pervasive nature of these technologies will allow less skilled and resourced criminals to gain access to markets and tools that were previously out of their reach.

International conflict

30. Serious and organised crime will continue to distort and impede inclusive and sustainable economic growth, corrupt democratic processes, damage social cohesion and exacerbate exclusion. This is particularly true in fragile states, and notably post-conflict settings, where illicit economies and drug and weapons trafficking networks can thrive and become entrenched as conflict ceases. By perpetuating impediments to development, serious and organised crime will increase dependency on aid, deter legitimate business investment and drive violence, conflict and terrorism.

Exiting the European Union (EU)

31. Criminals will look to exploit any vulnerabilities they can find in our border and security arrangements as we exit the EU. With threats evolving faster than ever before, it is in the clear interest of the UK and its allies to sustain the closest possible cooperation in tackling serious and organised crime and other threats to national security. It is in the interests of all citizens for the UK and EU to remain responsive to any changes in the activities and techniques employed by serious and organised criminals resulting from the UK’s departure.

32. At present, the UK and its law enforcement agencies and prosecuting authorities work with other EU Member States through a range of EU tools and measures that help facilitate this cooperation. We will continue to play a leading international role in countering serious and organised crime during and following the UK’s exit from the EU. We will seek to maintain deep and close cooperation with European partners on law enforcement, criminal and security matters and, in some areas, including at the border, we will identify and take forward new opportunities to strengthen our security.

Part Two: Strategic Approach

Aim and objectives

33. Despite significant progress in delivering the 2013 Serious and Organised Crime Strategy, the scale of the challenge we face is stark and, for this reason, we have revised our approach. Our aim is to protect our citizens and our prosperity by leaving no safe space for serious and organised criminals to operate against us within the UK and overseas, online and offline.

34. This strategy sets out how we will mobilise the full force of the state, from the capabilities of our security and intelligence agencies and law enforcement, including police forces, to the powers of local authorities to target and disrupt serious and organised criminals. We will equip the whole of government, the private sector, communities and individual citizens to align their efforts in a single collective endeavour to rid our society of the harms of serious and organised crime. We will pursue offenders through prosecution and disruption, bringing all of our collective powers and tools to bear. We will: prevent people from engaging in serious and organised crime; protect victims, organisations and systems from it; and prepare for when it occurs, mitigating the impact. We will strengthen our global reach to confront the threat before it comes to our shores.

35. This strategy provides a framework and outlines a set of capabilities which are designed to respond to the full range of serious and organised crime threats. We have four overarching objectives to achieve our aim:

- 1. Relentless disruption and targeted action against the highest harm serious and organised criminals and networks We will target our capabilities on criminals exploiting vulnerable people, including the most determined and prolific child sex offenders and we will proactively target, pursue and dismantle the highest harm networks affecting the UK. We will use new and improved powers and capabilities to identify, freeze, seize or otherwise deny criminals access to their finances, assets and infrastructure, at home and overseas including Unexplained Wealth Orders and Serious Crime Prevention Orders. At the heart of this approach will be new data, intelligence and assessment capabilities which will allow the government, in particular the NCA, to penetrate and better understand serious and organised criminals and their vulnerabilities more effectively and target our disruptions to greater effect.

- 2. Building the highest levels of defence and resilience in vulnerable people, communities, businesses and systems We will remove vulnerabilities in our systems and organisations, giving criminals fewer opportunities to target and exploit. We will ensure our citizens better recognise the techniques of criminals and take steps to protect themselves. This includes working to build strong communities that are better prepared for and more resilient to the threat, and less tolerant of illegal activity. We will also identify those who are harmed faster and support them to a consistently high standard.

- 3. Stopping the problem at source, identifying and supporting those at risk of engaging in criminality We will develop and use preventative methods and education to divert more young people from a life of serious and organised crime and reduce reoffending. We will use the government’s full reach overseas to tackle the drivers of serious and organised crime.

- 4. Establishing a single, whole-system approach At the local, regional, national and international levels, we will align our collective efforts to respond as a single system. We will improve governance, tasking and coordination to ensure our response brings all our levers and tools to bear effectively against the highest harm criminals and networks. We will expand our global reach and influence, increasing our overseas network of experts to ensure the UK’s political, security, law enforcement, diplomatic, development, defence relationships and financial levers are used in a more coordinated and intensive manner. And we will work to integrate with the private sector, pooling our skills, expertise and collective resources, co-designing new joint capabilities, and designing out vulnerabilities together.

36. As a result, we will be able to measure and demonstrate that:

a) We have significantly raised the risk of operating for the highest harm criminals and networks within the UK and overseas, online and offline, by ensuring:

- new data and intelligence capabilities have targeted and disrupted serious and organised criminals and networks in new ways;

- a range of partnerships and working practices are embedded in the UK that enable us to sharpen and accelerate our response;

- overseas partners are working with us more often, more collaboratively and more effectively to target serious and organised crime affecting the UK; and

- we are arresting and prosecuting the key serious and organised criminals, stopping their abuse, denying and recovering from them their money and assets, dismantling their networks and breaking their business model.

b) Communities, individuals and organisations are reporting they are better protected and better able to protect themselves; and victims are better supported to recover from their abuse or exploitation.

c) Fewer young people are engaging in criminal activity or reoffending.

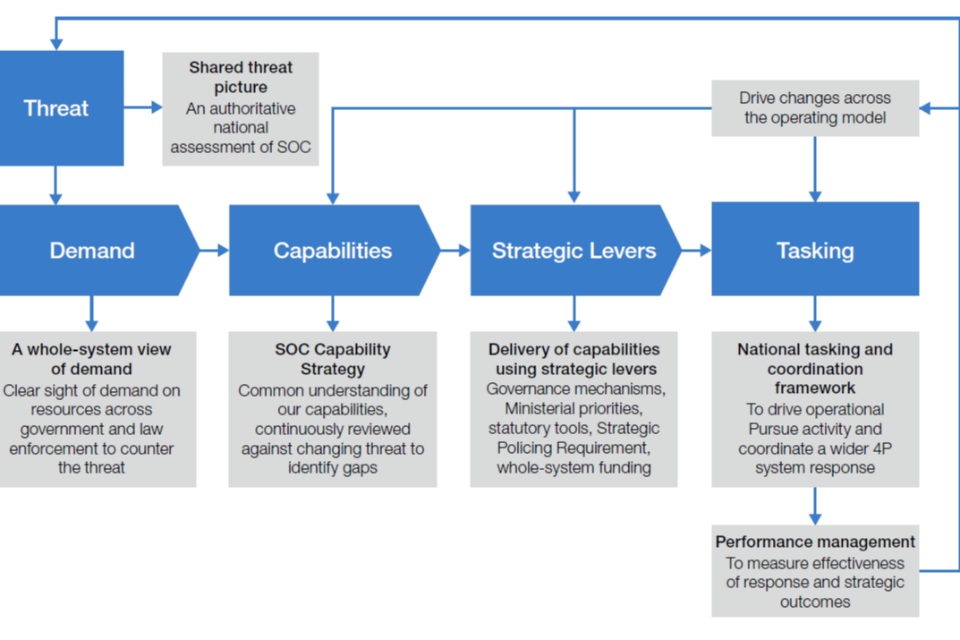

37. We will maintain the Pursue, Prepare, Protect and Prevent delivery framework, sometimes known as ‘4Ps’, as it provides a coherent approach for all partners involved in countering serious and organised crime, from preventing crime in the first place to convicting perpetrators and helping victims. The four strands, shown alongside our aim and objectives in Figure 2, are:

- to Pursue offenders through prosecution and disruption

- to Prepare for when serious and organised crime occurs and mitigate impact

- to Protect individuals, organisations and systems from the effects of serious and organised crime

- to Prevent people from engaging in serious and organised crime

Figure 2 – Serious and Organised Crime (SOC) Strategy framework

Protect our citizens and our prosperity by leaving no safe space for serious and organised criminals to operate against us within the UK and overseas, online and offline

| PURSUE offenders through prosecution and disruption | PREPARE for when SOC occurs and mitigate impact | PROTECT individuals, organisations and systems | PREVENT people from engaging in SOC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relentless disruption and targeted action against the highest harm serious and organised criminals and networks | 2. Building the highest levels of defence and resilience in vulnerable people, communities, businesses and systems | 2. Building the highest levels of defence and resilience in vulnerable people, communities, businesses and systems | 3. Stopping the problem at source, identifying and supporting those at risk of engaging in criminality |

| 4. Establishing a single whole-system approach, expanding our global reach and pooling skills and expertise with the private sector | 4. Establishing a single whole-system approach, expanding our global reach and pooling skills and expertise with the private sector | 4. Establishing a single whole-system approach, expanding our global reach and pooling skills and expertise with the private sector | 4. Establishing a single whole-system approach, expanding our global reach and pooling skills and expertise with the private sector |

Part Three: Our Response

Objective 1: Relentless disruption and targeted action against the highest harm serious and organised criminals and networks

38. The priority of the 2013 Serious and Organised Crime Strategy was to prosecute and relentlessly disrupt serious and organised criminals. We have made significant progress in establishing the powers, partnerships and law enforcement structures to achieve this, including the creation of the NCA. The government will continue to prioritise ensuring law enforcement agencies have and use all the powers and levers at their disposal. We will invest in new capabilities and take significant new measures that strengthen our ability to stop abusers, target dirty money and reduce economic crime. We will also sharpen and deepen our specialist online capabilities to combat cyber crime and other online offences, and put data and intelligence at the heart of our law enforcement approach. We will maximise our ability to intervene upstream and at our borders.

Law enforcement capabilities and powers

39. The NCA is the lead law enforcement agency for serious and organised crime in England and Wales. It has a wider remit than its predecessors to strengthen the UK’s borders, fight economic crime, fraud, corruption and cyber crime, and protect children and young people from sexual abuse and exploitation. The agency leads, supports and coordinates activity across law enforcement, locally, regionally, nationally and internationally. It works in close collaboration with the UK Intelligence Community (UKIC), police forces across the UK, international police forces and other law enforcement partners, including through its two-way tasking and coordination arrangements. The NCA publishes the annual National Strategic Assessment of Serious and Organised Crime which provides a single picture of the threats the UK faces.

40. Since its inception, NCA operations have led to over 12,000 arrests in the UK and overseas. Over 7,800 children have been safeguarded. Over ten million schoolchildren in the UK have been helped to stay safe online through the agency’s ThinkUKnow[footnote 33] programme. NCA targeting of criminal assets has resulted in £22 million of cash forfeited, £34 million of civil recovery and tax receipts and £51 million worth of confiscation orders paid. NCA operations have also resulted in the seizure of over 1,700 guns and 1,000 other firearms, as well as 19 tonnes of heroin and 335 tonnes of cocaine.

41. As a result of the Spending Review (SR) announced in autumn 2015, £200 million of capital funding was made available to the NCA over the period 2016–20, an approximately 25% increase on the previous SR settlement. The uplift was provided in order to support continued investment in the NCA’s capabilities, designed to enable the NCA’s transformation into a world-leading law enforcement agency.

42. The nine Regional Organised Crime Units (ROCUs) are the principal link between the NCA and police forces in England and Wales. ROCUs are regional police units with 14 core specialist capabilities, used to investigate and disrupt serious and organised crime, delivered regionally but accessible to all police forces through an established tasking mechanism. ROCU operations led to a total of 2,052 disruptions in 2017/18, while their support to partners contributed to more than 2,675 further disruptions. In addition to the significant investment by Police and Crime Commissioners, the government has invested over £160 million in uplifting the capabilities of the ROCUs since 2013. In 2017 the Home Office announced £40 million to enhance ROCU capabilities over the subsequent three years.[footnote 34]

43. Much of the impact of serious and organised crime is felt at the local level and the local response continues to be led by police forces. Police force responsibilities focus on: local policing across the ‘4Ps’ in response to national priorities; identification and management of local threat; and local safeguarding of children and adults. The National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) coordinates the operational response of police forces across the UK, and helps forces to improve and provide value for money. There is a dedicated lead in NPCC for serious and organised crime who chairs a Serious and Organised Crime Programme Board and has an action plan to help improve the response of police forces. NPCC is also working with the Home Office to provide peer support to forces, including sharing best practice and providing access to subject matter experts.

44. UKIC continues to increase its contribution to tackling serious and organised crime. This includes initiatives such as the NCA and GCHQ Joint Operations Team (JOT), and measures by the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) to reduce the harm to the UK from cyber crime. We are providing £3.6 million in 2018/19 and £4.3 million in 2019/20 for GCHQ which will: make it harder for offenders to use communications technology for the sexual abuse of children; and enable the piloting of an online portal to allow government, charities, companies and academia to improve information sharing and collaborate to improve child protection outcomes.

45. A wide range of other investigative and enforcement agencies play a key role in tackling specific serious and organised crime threats. These include but are not limited to: HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC), which received additional investment in the Autumn Budget 2017 to tackle the enablers and facilitators of tax fraud; Immigration Enforcement; and the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) which both investigates and prosecutes serious fraud, bribery and corruption, and associated money laundering. The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) prosecutes all cases for the NCA, police, HMRC and others and undertakes confiscation and civil recovery. A full list of the different organisations involved in tackling serious and organised crime is at Annex A.

46. As part of the system-wide response, the NCA will receive additional resources in 2018–2020 to lead the development of new national capabilities such as the National Assessment Centre (NAC), the National Data Exploitation Capability (NDEC), and the National Economic Crime Centre (NECC), announced by the then Home Secretary in December 2017. This will ensure they have world leading capabilities to target, pursue and dismantle the highest harm serious and organised criminals and those corrupt elites and criminals who seek to wash their dirty money in and through the UK.

47. The recent NCA and NPCC joint bid to the Police Transformation Fund (PTF) secured £2.2 million for an immediate uplift to work to tackle online child sexual exploitation. This will fund a significant expansion of the NCA and GCHQ JOT to increase their capability to target the most dangerous and determined online child sexual exploitation offenders. This means more officers working to identify those perpetrators who hide behind anonymisation. The uplift will create a pipeline of intelligence that will expose groomers masquerading as children, high risk offenders using technology to anonymise their presence and offenders accessing live streaming overseas.

48. We will commit £500,000 to provide law enforcement agencies with a better picture of child sexual exploitation offending on the dark web. This will use available data to identify, assess and pursue the highest risk suspects of interest who are impacting the UK, so we can prioritise our resources against them, in collaboration with international partners.

49. Through our £40 million support to the Fund to End Violence Against Children to 2019-20, we have also encouraged a stronger focus on the need to develop innovative technological solutions to break new ground in tackling online child sexual exploitation. Through this in 2018 we have funded the development of ‘Solis’ – an innovative tool for law enforcement to speed up identification of material relating to child sexual exploitation and abuse on the Dark Web.

Figure 3 – Legislation and key powers introduced since 2013

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOC Strategy 2013 | Modern Slavery Strategy | Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 | National Cyber Security Strategy | Anti-Corruption Strategy | SOC Strategy 2018 |

| Crime and Courts Act 2013 | Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 | Modern Slavery Act 2015: - higher maximum penalties - new civil orders - new maritime enforcement powers |

Pschoactive Substances Act 2016 | Policing and Crime Act 2017: - further maritime enforcement powers - tightening Firearms Act loopholes - stronger penalties for breach of financial sanctions |

Data Protection Act 2018 |

| Serious Crime Act 2015: - participation offence - Proceeds of Crime: longer default sentences, lower test for asset restraint - improved Serious Crime Prevention Orders - new Computer Misuse offences -new child sexual exploitation offences |

Immigration Act 2016 | Criminal Finances Act 2017: - new powers to tackle illicit wealth, including Unexplained Wealth Orders - new information sharing powers - improvements to SARs[footnote 35] - corporate failure to prevent tax evasion |

|||

| Investigatory Powers Act 2016 | |||||

50. As set out in Figure 3, since 2013 the government has introduced robust new legislation, including the Serious Crime Act 2015, Modern Slavery Act 2015 and Criminal Finances Act 2017, to ensure enforcement agencies have the powers and tools they need to relentlessly disrupt serious and organised criminals. These include significant new measures such as:

- Improved Serious Crime Prevention Orders to place conditions on an individual that can include blocking financial or business dealings or restricting travel and meetings with criminal contacts

- Telecommunications Restriction Orders to provide the power to permanently disconnect illicit mobile phones being used in a prison;

- Unexplained Wealth Orders that require either a politically exposed person, or a person who is thought to be involved in serious crime, to explain any assets they have obtained (particularly property) which are disproportionate to their known income

51. Relentless disruption continues to be a key tenet of our response to serious and organised crime, and we remain committed to bringing the full force of the state to bear on the threat. We will ensure operational partners target and coordinate disruptive activity so that we have the greatest impact on the most serious criminals and groups impacting on the UK. The NCA has catalogued the extensive criminal and civil powers available to law enforcement agencies. These range from powers to seize the proceeds of crime and deny criminals access to their assets, to immigration powers to remove or deport offenders, curtail or refuse leave to remain, refuse British nationality or prevent travel to the UK in the first place.

52. There are a wide range of other tools at our disposal to help exploit weaknesses in criminal networks and to make the lives of serious and organised criminals as difficult as possible, from vehicle prohibition and civil tax recovery to gang injunctions and local authority licensing powers. These are set out in the Menu of Tactics[footnote 36] published by the College of Policing, which includes hundreds of powers, tools and interventions across national authorities and local agencies to prevent and disrupt serious and organised crime. We will take a coordinated and systematic approach to using to their fullest extent the range of powers available to law enforcement and wider partners.

Powers to access data and their oversight

53. The ability to harness data is vital both to understand and disrupt serious and organised crime effectively. Recent changes in legislation have resulted in new powers and the ability to use previously inaccessible information. The 2018 Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act, which was passed by the US Congress, paves the way for bilateral agreements between the US and qualifying foreign nations to enable access to the content of communications from overseas companies in serious crime and terrorism investigations, regardless of where the information is geographically stored. The UK plans to be the first country to enter into a bilateral agreement with the US.

54. The Investigatory Powers Act 2016 (IPA) affords relevant agencies, in certain circumstances, the ability to intercept communications and to use equipment interference. It provides an authority framework for the examination of bulk data. It also puts additional responsibilities on service providers to retain communications data. The IPA has transformed the law relating to the use and oversight of investigatory powers, strengthening safeguards and introducing new oversight arrangements. The authorisation of the most intrusive investigatory powers, such as intercepting communications, requires that both a Secretary of State and a Judicial Commissioner must be satisfied that warrants are necessary and proportionate before they can be issued. The Investigatory Powers Commissioner provides essential oversight of the powers provided by the Act and produces a public report annually.

55. The introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Data Protection Act in 2018 increases the protection afforded by the current Data Protection Act. These arrangements provide full and transparent assurance to the public that their data will be protected and used lawfully by the government and in a way that is proportionate to the threat posed. At the core of the NDEC model will be control mechanisms around the acquisition, collection, storage, retention and use of data in line with legislation and standards set out in the Common Data Standards, the Data Ethics Framework,[footnote 37] the IPA, the Computer Misuse Act 1990 and the GDPR.

Child sexual exploitation and abuse

56. The Home Office will invest £37.7 million over the next two years on tackling child sexual exploitation and abuse: we will prioritise enhancing our ability to detect and disrupt offenders online. The NCA’s Child Exploitation and Online Protection (CEOP) Command leads, supports and coordinates the law enforcement response to child sexual exploitation and abuse and works closely with law enforcement and intelligence agencies in the UK and overseas, to identify victims and pursue offenders. This is supported by close collaboration with civil society organisations like the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) and the US National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Through coordinated activity, the NCA and police arrest around 400 offenders in relation to online child sexual exploitation and abuse and safeguard over 500 children every month.

57. We have already provided £20 million for undercover capabilities to tackle online child sexual exploitation within ROCUs and a near-doubling of CEOP’s investigative capability. In 2015, we launched the JOT as a collaborative venture between the NCA and GCHQ. The team has significantly increased our understanding of the challenges around disrupting the most serious and prolific UK offenders.

58. All UK police forces and the NCA are connected to the Child Abuse Image Database (CAID), launched in 2014. It contains more than ten million indecent images of children and 30 million hashes (the digital fingerprint of an image). Law enforcement experience is that around 70% of indecent images identified in its operations are held on CAID. CAID provides law enforcement agencies with effective tools to search seized devices for indecent images of children, reduce the time taken to identify such images and increase the ability to identify victims. In 2017/18, UK law enforcement identified 664 victims within indecent images of children compared to 177 in 2014/15.

59. To keep pace with the threat, we will increase our ability to target and disrupt the worst offenders. The Home Office will be investing an extra £21 million over the next 18 months to bolster the response of our law enforcement and intelligence agencies to these types of crimes. This money will give law enforcement new tools and techniques to investigate high end offenders at scale. We will expand the joint taskforce run by police, NCA and GCHQ, bringing together world class expertise in intelligence gathering and investigation. This will prevent offenders from operating with impunity in online forums and chatrooms. We will identify, assess and pursue the highest risk suspects, bringing the full capabilities of our security apparatus to bear.

60. We will fund an information sharing capability for tackling child sexual exploitation and abuse that will ultimately form the basis for a sustained partnership between law enforcement agencies, UKIC, government, charities and industry. Under the leadership of the Home Office, stakeholder organisations will share information to support closer collaboration on emerging threats, learning from working practices used against the cyber threat. We expect to be conducting the first experimental trials in January 2019, leading to development of a new sustainable capability during 2019/20. We will also enable law enforcement agencies to probe digital forensic and other intelligence material to help us understand how people are drawn into offending, so that we can target interventions to prevent abuse before it happens.

61. Alongside a tough law enforcement response to bring offenders to justice, it is crucial to prevent offending in the first place. We will provide a further £2.6 million to collaborate with child protection organisations to improve our understanding of offender behaviour and prevent future offending. This includes ongoing support for an innovative programme of work with the Lucy Faithfull Foundation to deter online offending through their StopItNow![footnote 38] Campaign. This work aims to demonstrate to offenders and potential offenders the harm and suffering caused to child victims, to their own families, and the legal consequences they face. We will also continue to address the risk of first-time and unwitting offending by relaunching our Steering Clear campaign in December 2018 with the Marie Collins Foundation and IWF.

62. We also expect industry to play its part in combatting the threat. In recent years there has been some good work in this area. For example, Microsoft has developed PhotoDNA which has helped to identify and take down child sexual abuse imagery from the internet. Google launched a new artificial intelligence tool in September 2018 to identify and prioritise the most likely child sexual abuse imagery for human reviewers. And when Google and Microsoft made changes to their algorithms to make it harder to find child sexual abuse material in search results, Google reported up to thirteen-fold reduction in search attempts. However, in view of the scale and sophistication of the threats we face, more must be done.

63. Companies must be at the forefront of efforts to deny offenders the opportunity to access children and child sexual abuse material via their platforms and services. In particular, we expect progress on the following priority areas:

- child sexual abuse material should be blocked as soon as companies detect it being uploaded

- companies must stop online grooming taking place on their platforms

- companies must work with government and law enforcement to stop live-streaming of child abuse

- companies should be demonstrably more forward leaning in helping law enforcement agencies to deal with child sexual exploitation (including collaboration between offenders)

- we expect to see improved openness and transparency and a willingness to share best practice and technology between companies

- child sexual exploitation and abuse sites must no longer be supported by advertising

Case Study

The case of Matthew Falder demonstrates the depravity of serious and organised criminals. It also highlights the harm posed online by offenders with a high degree of technological sophistication, who are able to use multiple fake online identities and a variety of encryption and anonymisation techniques, and stay hidden in the darkest recesses of the Dark Web to try to conceal their criminal activities.

Falder was a university academic who is now serving a sentence of 25 years’ imprisonment after admitting 137 charges. His conviction followed an investigation by the NCA into horrific online offending which included encouraging the rape of a four year old boy. Falder approached more than 300 people worldwide and would trick vulnerable victims – from young teenagers to adults – into sending him naked or partially-clothed images of themselves. He would then blackmail his victims to self-harm or abuse others, threatening to send the compromising images to their friends and family if they did not comply. He traded the abuse material on ‘hurt core’ forums on the Dark Web dedicated to the discussion, filming and image sharing of rape, murder, sadism, paedophilia and degradation.

This was a very complex NCA investigation involving US Homeland Security Investigations, the Australian Federal Police and Europol to share and develop intelligence against the suspect, supported by GCHQ and other partners. Each of the hundreds of individuals who had been approached by Falder was reviewed by the NCA’s child protection advisors for potential safeguarding.

Strengthening our ability to target dirty money and reduce economic crime

64. We will prioritise tackling illicit finance, given the critical importance of denying the highest harm networks the ability to hide, move or use their profits. We will identify and seize their assets and make it more difficult for them to move and hide their illicit funds in the UK, by targeting the complicit, negligent or unwitting professional enablers who are often key to moving illicit funds through the UK and global financial systems.

65. The power to locate and seize money made by criminals (known as asset recovery) can disrupt criminal networks, prevent the funding of further illegal activity and compensate victims for their ordeals. We have strengthened the legal powers for tackling money laundering and recovering criminal assets through the Serious Crime Act 2015 and Criminal Finances Act 2017. We introduced new Money Laundering Regulations in 2017 to embed the latest international standards in the UK. And we created new Asset Confiscation Enforcement (ACE) teams which, at a cost of just over £5 million in the last three years, have assisted in the recovery of over £83 million.

66. Joint working with the private sector has significantly improved our response. The creation of the Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce (JMLIT) in 2014 provided a new mechanism for law enforcement and the financial sector to share information and work more closely together to detect, prevent and disrupt money laundering and wider economic crime. Since April 2015, JMLIT enquiries have identified over 3,000 bank accounts that were previously unknown to law enforcement, and over 100 new suspects in criminal investigations. In total, 99 arrests have been made, facilitated, or supported by JMLIT activity.

67. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) reviewed in 2018 the UK’s anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist finance regime against the international standards it sets. The UK has a strong and effective regime to tackle money laundering and terrorist finance, and to recover illicit funds, and we will consider carefully recommendations made by FATF that will further enhance our response.

68. We will ensure the full and effective use of the powers created by the Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Unexplained Wealth Orders, expansion of availability of civil recovery powers and bank account forfeiture) and the Serious Crime Act 2015 (compliance orders). Financial investigation techniques remain under-used. We want to increase the use of these powers and the asset recovery opportunities brought about by good financial investigations. We will therefore fund an independent review of the Proceeds of Crime Centre, hosted in the NCA, which has a statutory function to train financial investigators. We will review the training syllabus to ensure financial investigators are capable of dealing with the most complex cases. We will publish research on the benefits of financial investigation to guide future investments and financial investigations by operational agencies. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) will include analysis of the use of financial intelligence as part of the PEEL inspections in 2018/19.

The Serious Crime Act 2015 provided an emphasis and further powers to ensure enforcement of confiscation orders. Among others, the Act introduced the following provisions:

- new compliance orders to ensure that a confiscation order is effective

- substantially reduced time to pay for confiscation orders

- increased default sentences for those who fail to pay their orders

- a new power for a judge to make a binding finding over third party ownership of property

The Criminal Finances Act 2017 enhanced the Suspicious Activity Reports regime and extended and strengthened civil asset recovery powers. The Act:

- introduced Unexplained Wealth Orders requiring the respondent to explain their lawful ownership and the means by which they acquired specified property

- provides law enforcement agencies with significant new civil powers to seek the forfeiture of illicit funds held in bank and building society accounts, and assets that are personal or moveable

- enables information sharing on a voluntary basis where there is suspicion of money laundering, generating better intelligence for law enforcement agencies, and helping firms better protect themselves

- extended the availability of powers to the SFO and, in respect of civil recovery powers, to HMRC and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

69. In December 2017, the government announced measures to improve the UK’s response to economic crime. We are investing up to £4.6 million in 2018/19 to establish the National Economic Crime Centre (NECC) that will act as the national authority for the UK’s law enforcement response to economic crime, drawing on operational capabilities in the public and private sector. It will ensure that our local, regional, national and international work is driven by a single set of priorities. It will task and coordinate multi-agency operations to achieve the greatest sustained impact on the threat. It will maximise the value of improved intelligence and data capabilities such as the NAC and NDEC. We are also investing in improved frontline financial investigative capabilities, including £2.8 million in 2018/19 for local police forces.

70. We will reform the Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) regime through a public-private partnership. SARs are submitted by the regulated sector to alert law enforcement, at all levels, to activity that might indicate money laundering or terrorist financing. The number of SARs has doubled over the last ten years,[footnote 39] and the efficiency of the SARs regime could be substantially enhanced. We will renew and replace the IT system with a more sophisticated system that is better able to meet today’s challenges. This is due to be completed by 2020.

71. The reform programme will enhance the way that SARs intelligence is used by law enforcement and will produce clearer and better guidance to the regulated sector, allowing their very significant resources to be better targeted to have the most effect. In support of this, the NCA will increase the size of the UK Financial Intelligence Unit (UKFIU) which receives, analyses and disseminates intelligence submitted through the SARs regime. We are also supporting the Law Commission’s ongoing review of the consent regime[footnote 40] and will facilitate reform where possible within the current regulatory and legal environment.

72. Reducing the corruption risk to the UK and strengthening the integrity of the UK as an international financial centre also forms an important part of our enhanced response to illicit finance. Professional enablers, such as lawyers, accountants and estate agents, are a crucial gateway for criminals looking to disguise the origin of their funds.[footnote 41] They can facilitate illicit financial flows through and into the UK due to lack of awareness, negligence or complicity. In 2017, HM Treasury legislated to set clear, high standards of supervision for all professional body supervisors, and the government has created a new body at the FCA, the Office for Professional Body Anti-Money Laundering Supervision (OPBAS). It has the powers to publicly censure professional body supervisors and can recommend that HM Treasury remove them as supervisors.

73. The Home Office will expand the ‘Flag It Up’[footnote 42] campaign to increase awareness within the accountancy and legal sectors of money laundering. The 2016/17 campaign demonstrated that accountants and lawyers who recognised ‘Flag It Up’ were twice as likely to submit a SAR, compared to those professionals who did not have knowledge of the campaign. We will also expand the campaign to encourage increased compliance amongst professionals in the property sector.

74. Successive UK governments have made it progressively simpler and cheaper to establish companies, which while benefiting overall ease of doing business, has also been exploited by criminals to set up UK-registered companies for illicit purposes. Companies House maintains the public register of limited companies, and the government has taken steps to improve information sharing between Companies House and law enforcement agencies. We will now go further to improve the integrity of the register, requiring regulated sectors to report where, through their due diligence, they have identified discrepancies with information held on the public register. Following the FATF evaluation of the UK’s anti-money laundering regime, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) will review options to improve the accuracy and integrity of the register.

75. The government will publish an action plan on asset recovery, including support to the Law Commission’s work to identify reforms to improve the confiscation regime, due to complete by 2020. As part of the plan, we will explore how private firms could assist in asset recovery. We will also increase the funding by 50% to £7.5 million in 2018/19 for key national capabilities such as the network of ACE teams.

76. The UK established a public register of company beneficial ownership information in 2016. In July 2018, we published draft legislation for the creation of a register of beneficial owners of overseas companies owning property in the UK. This follows the commitment made at the Anti-Corruption Summit in 2016 to combat money laundering and increase the transparency of the UK property market. The new register will be the first of its kind in the world and will aim to make it more difficult for kleptocrats and serious and organised criminals to hide their illicit funds in the UK.

77. We will also tighten rules on UK Limited Partnerships, including Scottish limited partnerships (SLPs) to prevent abuse by criminals. Limited partnerships continue to fulfil important functions in key sectors of our economy. However, the NCA has identified a disproportionately high volume of suspected criminal activity involving SLPs, and there are ways to strengthen and update the legal framework. The government launched a consultation in April 2018, which included proposals to strengthen and update the legal framework for limited partnerships. The government will set out reforms to the law governing limited partnerships, including SLPs, by the end of the year. Reforms will require primary legislation and it would be our intention to legislate as soon as Parliamentary time allows.

78. In preparation for the UK’s exit from the European Union, Parliament passed the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act, which received Royal Assent in May 2018. This primary legislation will provide the UK with powers to impose sanctions, including for human rights purposes. The government could use these powers to address corruption, where this meets one of the purposes set out in the Act, for example, furthering a UK foreign policy objective. We are working to operationalise the Sanctions Act for when the UK leaves the EU. The government will make decisions on the use of sanctions in the future where appropriate, as part of the UK’s wider foreign policy and national security toolkit. The Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act will also require Overseas Territories to introduce public beneficial ownership registers.

Sharpening and deepening specialist online capabilities

79. Our programme to tackle cyber crime is underpinned by wider objectives set out in the NCSS and by funding from the National Cyber Security Programme (NCSP) and Home Office. Over the last two years, we have invested over £50 million in strengthening the capabilities of the NCA’s National Cyber Crime Unit (NCCU) and continuing to develop cyber teams within each of the ROCUs in England and in Wales. In 2018/19, we will invest a further £50 million to enhance NCA and ROCU digital forensics, intelligence and data-sharing capabilities, as well as to ensure every police force in England and in Wales has a dedicated specialist cyber crime unit to increase local investigative capabilities.

80. The Home Office will lead a three year programme with an initial investment of £4.5 million, to enhance our specialist Dark Web skills and capability, through reinforcing the work of the UKIC and the NCA’s Dark Web Intelligence Unit, and investing in strong working partnerships with other countries. In 2019, the Home Office will launch a national training programme, ensuring those working in this area are equipped to investigate properly and prosecute those who commit offences on the Dark Web.

Harnessing Science and Technology

We need to be at the leading edge of developments in data analytics, biometrics, screening technologies, behavioural and social sciences, continuously innovating to stay ahead of the threat and keep pace with the rapid rate of change. We will support initiatives that seek to explore the ethics of using artificial intelligence in the exploitation and interpretation of big data. This will involve use of innovative detection technologies and algorithms to detect the concealment of weapons and analytical tools that alert us to patterns in communications that might indicate sexual exploitation.

The Home Office will develop a cross-government Science, Technology, Analysis and Research (STAR) strategy. This will consider our response to serious and organised crime and terrorism, taking a full spectrum approach to countering sophisticated threats and ensuring the transfer of learning and knowledge regardless of threat type. We will develop new relationships with wider government partners, such as BEIS, DCMS and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), to leverage industrial strategy research and development investments. We will also strengthen our partnerships with industry and academia to deliver innovative solutions and explore opportunities to strengthen our collaboration with our priority international partners, including the Five Eyes security partnership, ensuring we understand and are in a position to exploit the global nature of technological change.

In the communications environment, technological advancements can have a profound impact on law enforcement’s ability to detect and investigate criminal activity. Threat and Risk Assessment, Capability Exploration and Research (TRACER) is an NCA-led community hub which examines technological developments in their wider context and the implications for serious and organised crime. TRACER monitors changes in the communications environment, including those resulting from legislative change, social trends and commercial drivers, and assesses the likely opportunities and threats for operational outcomes. It also coordinates the development of the community’s responses to mitigate threats and exploit opportunities.

Putting data and intelligence at the heart of our approach

81. To enable the government and law enforcement agencies, in particular the NCA, to more effectively penetrate criminal networks, we will place new data, intelligence and assessment capabilities at the heart of our response, complemented by a new intelligence operating model.

82. We will establish a multi-agency National Assessment Centre (NAC) within the NCA. The NAC will fuse data, intelligence and open source information to produce a single understanding of serious and organised crime threats. It will draw on the assessments of law enforcement agencies at all levels and work with UKIC to develop our understanding of online threats and vulnerabilities in particular, including cyber crime and child sexual exploitation and abuse. It will identify the National Intelligence Requirements (NIRs) which highlight the gaps in our understanding and direct partners to fill them. Joint working between the NAC and other assessment bodies, such as the NCSC on cyber crime and the Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre (JTAC) on specific overlaps between serious and organised crime and terrorism, will also ensure we have a comprehensive understanding of national security risks in the round.

83. NAC assessments will drive the operational response across the system, informing the investigations and interventions of the NCA, wider law enforcement agencies and the multi-agency NECC. The NAC will be a key customer of the NDEC (outlined further below), using its data outputs to underpin assessments, helping to target activity against high end criminals and, at an earlier stage, spot patterns and identify new vulnerabilities that criminals have begun to exploit.

84. The work of the NAC and our reformed approach to intelligence includes increasing the number of analysts with the requisite skills, and building consistent standards of professionalism around intelligence across the national security and law enforcement communities. This will be taken forward by the Professional Head of Intelligence Analysis, the College of Policing (through the Intelligence Professionalisation Programme and review of the Authorised Professional Practice for Intelligence Management) and NPCC (through the National Police Intelligence Strategy 2017-2025).

85. The Government Agency Intelligence Network (GAIN) provides an essential gateway for sharing intelligence between its members.[footnote 43] It is fundamental to the work carried out by local disruptions teams who, working closely with the public and private sectors, use non-criminal justice techniques and non-traditional policing methods to disrupt local organised crime groups. In 2018 a new National GAIN Intelligence Hub was established to provide a single point of contact for its member agencies to gather or share intelligence. The enhancement of GAIN will support the development of intelligence and data capabilities within the NCA. It will feed into the NAC and NDEC and support better outcomes at the regional level, contributing to a single and enhanced understanding of the threat.

86. We will transform the way we use data to tackle serious and organised crime by building a new National Data Exploitation Capability (NDEC) within the NCA, in collaboration with law enforcement and national security partners. The NDEC will be a national central capability which will significantly reduce the time taken to ingest, process and exploit existing data which support law enforcement agencies’ responses to serious and organised crime. The NDEC will proactively acquire new and underused datasets and use the latest data science to identify patterns in the data and links between different entities (such as offences, people, locations, vehicles or communications), adhering to national data standards and strategies.

Improving the evidence base

87. To enhance the evidence base and harness the expertise of the academic sector, the Home Office has published a prioritised set of research requirements to support this strategy, after working with partners to review the existing evidence to identify where there are gaps, and sources of data and funding. One immediate research requirement will be to improve our understanding of criminal markets. The NAC and Home Office will undertake pilot projects to understand how market forces such as supply and demand apply to different illicit markets, and test new ways of undermining the business models of organised crime groups by targeting law enforcement activity in innovative ways.

Firearms and Drugs

We work nationally to reduce the threat to the UK from the criminal use of firearms, and with our international partners and across law enforcement to disrupt firearms trafficking into the UK. Our focus on the heightened threat from firearms has evolved over recent years. Following the terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015, in which automatic weapons were used to inflict mass casualties, we increased the pace and breadth of our work.

In 2016 Operation DRAGONROOT tested the intelligence processes and operational response to the firearms threat. Led by the NCA and Counter-Terrorism (CT) Policing, it brought together national level coordination and operational support to the ROCUs, the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), Border Force, the National Ballistics Intelligence Service and the UK Armed Forces. The lessons learnt from the operation led to the establishment of a multi-agency firearms unit led jointly by the NCA and CT Policing. The unit coordinates law enforcement activity to improve our understanding of the threat from firearms. This includes focusing our international footprint on source countries of firearms trafficked into the UK and joint-working across law enforcement to disrupt supply. We are also taking action to improve firearms controls to prevent firearms being diverted from lawful ownership to the criminal marketplace. This includes greater regulation of antique firearms, statutory guidance for the police on firearms and shotgun licensing, and new offences on unlawfully converting imitation firearms and making defectively deactivated firearms available for sale.

There has been an upward trend in firearms offences since 2014, although they are still 32% below a decade ago and 43% lower than their peak in 2005/6. The Serious Violence Strategy sets out the drivers behind recent increases in serious violence including gun crime. Major factors include changes in the drugs market, including an increase in cocaine supply, an increase in the use of crack cocaine and the development of county lines networks as a means of drugs distribution. Tackling underlying issues such as misuse of drugs, county lines and criminal finances form part of the objectives outlined in this strategy.