Shooting Up: infections and other injecting-related harms among people who inject drugs in the UK, data to end of 2021

Updated 22 March 2023

Report produced in collaboration with Public Health Agency Northern Ireland, Public Health Scotland, and Public Health Wales.

Foreword

Drug use in the UK is among the highest reported in Western Europe and people who inject drugs (PWID) experience substantially worse health outcomes than the general population. Furthermore, overdose deaths and reports of non-fatal overdose are at an all time high. Existing health inequalities have likely been widened by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic response, which resulted in restricted access to essential services for PWID, including blood-borne virus (BBV) testing, treatment and harm reduction. The full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic response on infection transmission and long term health outcomes will take time to emerge and evaluate.

This report describes infections, as well as associated risks and behaviours among PWID in the UK to the end of 2021. Prevention, detection and treatment of infections related to injecting drug use remain issues of public health concern in the UK. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) remains the most common BBV infection among PWID in the UK. There is evidence for a continuing decline in the prevalence of chronic HCV infection in this population, which is largely due to improved testing and access to direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment. However, prevention of new and re-infections remains a challenge.

HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) prevalence remain comparatively low. However, outbreaks of HIV continue. In addition, there has been an increase in the proportion of people unaware of their HIV status. A concerted effort is required to improve testing, and to ensure that everyone living with HIV is aware of their status and can access treatment. HBV vaccination uptake has declined further and is the lowest level reported within the past decade. Improving vaccination uptake is necessary to ensure high levels of immunity and maintain the low number of infections.

Levels of reported sharing and re-use of injecting equipment remain high, which continues to drive transmission of blood-borne viruses (BBVs) and increase the risk of bacterial infections. Availability and access to sufficient supplies of sterile injecting equipment, as well as opioid agonist therapy (OAT), and wound care services, are key to preventing further spread of infections. The UK government’s Drug Strategy and investment of £780 million for English local authorities presents a key opportunity to expand and improve evidence-based harm reduction interventions.

Comprehensive approaches to infection prevention and treatment, as well as broader health and wellbeing, including peer-based models of service delivery are being rolled out on a larger scale. Ensuring that people with lived and living experience are involved in the design and delivery of these services can help to reach underserved groups and those not in contact with traditional services. This person-centred approach, combined with a whole-system approach to the prevention, detection and treatment of infections, is crucial for reducing health inequalities among this marginalised group, and to meet international elimination goals for HIV, HBV and HCV.

Dr Sema Mandal

Deputy Director for Blood Safety, Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Infections and HIV

Main messages and recommendations

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)

Chronic hepatitis C prevalence continues to decline, but prevention of new and re-infections remains a challenge.

HCV continues to be the most common BBV infection among PWID in the UK, with bio-behavioural survey data showing no evidence of a reduction in new HCV infections in recent years. However, there is evidence of a reduction in chronic HCV prevalence, which has occurred alongside the scale-up of DAA treatment in this population. The decline in chronic prevalence among PWID is likely to be due to better uptake of HCV treatment rather than improved prevention of new and re-infections through harm reduction initiatives. Insufficient provision of harm reduction poses a threat to the UK’s ability to achieve and maintain elimination. However, the UK government’s 10-year Drug Strategy released in April 2022 outlines significant investment to be used by local authorities in England to expand and improve evidence-based harm reduction interventions. The Scottish Government, Welsh Government and Northern Ireland Executive have set out their own strategies and funding.

The COVID-19 pandemic response continued to impact access to HCV testing in 2021. Ongoing initiatives that aim to improve diagnostic testing and treatment need to be monitored and evaluated to ensure they are equitable for all PWID living with HCV. It is important to continue to test those with ongoing risk regularly to identify re-infection and reduce the risk of transmission.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV)

HBV remains rare, but vaccine uptake has declined substantially.

Although HBV vaccination is recommended as high priority for all people who currently inject drugs, nearly 40% report that they have never been vaccinated. HBV infection in this population remains rare, but it is essential that vaccine uptake is improved to ensure high levels of immunity. Vaccination should be particularly promoted among PWID of younger age and recent initiates to injecting, for whom reported uptake is lower. Further work is needed to explore the facilitators and barriers to uptake of HBV vaccination to inform policy and practice.

HIV

HIV prevalence remains low and stable, but outbreaks continue.

HIV infections and outbreaks continue to occur among PWID, although overall prevalence among this group in the UK remains comparatively low. The proportion of those aware of their infection has declined; nearly one fifth of PWID in England, Wales and Northern Ireland were unaware of their infection in 2021. Disruptions to HIV testing services as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic response likely resulted in delayed testing and diagnosis for some people. However, missed opportunities for testing and prompt diagnosis also remain; 18% of PWID who currently inject drugs reported that they had never received a test, despite being in contact with services. It is important that PWID at ongoing risk are offered a diagnostic test regularly. Care pathways for those with HIV need to be optimised and maintained to ensure outcomes for PWID are equitable.

Bacterial infections

Preventable bacterial infections remain a problem.

Cases of bacterial infections among PWID have fallen since 2020, although this is mainly thought to be a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic response, which resulted in restricted access to healthcare services, reduced testing and reporting delays. To prevent rates of bacterial infections increasing, drug and alcohol services should facilitate easy access to needle and syringe programmes (NSPs), embed regular opportunities to discuss safe and hygienic injection practices with clients and provide low threshold and outreach wound care services. It is also important to provide prompt treatment for injection site infections and tetanus vaccination.

Read full Bacterial infections section below.

Injecting risk behaviours

Injecting risk behaviours have not improved.

Sharing and re-use of injecting equipment among PWID remains common. In 2021, a third of PWID reported inadequate provision of needles and syringes. A range of easily accessible harm reduction services for all PWID, including NSP and OAT, need to be provided. A better understanding of the range and scope of NSP provision in non-drug service settings is needed. Clients should be supported to use low dead space equipment, including detachable needles and syringes that have lower dead space, to further reduce the risk of BBV transmission. Socially excluded communities, such as PWID experiencing homelessness and those not currently in contact with drug and alcohol services, should receive additional targeted support to enable them to access harm reduction services, regular BBV testing and care.

Read full Injecting risk behaviours section below.

Drug use patterns

Changing patterns of psychoactive drug use remain a concern.

The changing patterns of psychoactive drug injection in the UK remain a concern, as changes in psychoactive drug preferences can lead to riskier injecting practices. Although the proportion of PWID reporting injection of crack cocaine has remained high in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, there has been an increase in reported injection of powder cocaine across the UK in recent years. The latter has been linked with ongoing BBV outbreaks in Scotland and Northern Ireland. There is a need for local treatment and harm reduction systems that can respond to both the increasing numbers and the specific needs of people who use crack and powder cocaine.

Read full Drug use patterns section below.

Fatal and non-fatal overdose

Rates of fatal and non-fatal overdose are at an all-time high.

Reports of both fatal and non-fatal overdose have increased in the UK, with overdose most common among people using and/or injecting opioids. This is in the context of improved availability of naloxone, an emergency antidote for opioid overdose, and increased self-reported carriage of take-home naloxone among PWID. Local areas should ensure that they commission readily accessible OAT, NSP and take-home naloxone services to meet service user needs and preferences. In addition, services working with PWID should provide materials to increase awareness of, and information about, overdose risks and provide training for peers and family members in overdose prevention, recognition and response.

Read full Fatal and non-fatal overdose section below.

COVID-19 impact

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on PWID and service provision.

Preliminary bio-behavioural and other surveillance and research data indicates PWID in the UK have been adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with access to services severely limited, including access to BBV testing and equipment for the safe use and/or injecting of drugs. Despite the disruption in services, novel approaches to delivery have been implemented to ensure continuity of access to interventions. It is important that these innovations are evaluated to assess the impact on outcomes, including national HIV and viral hepatitis elimination efforts, as well as health inequalities. It is likely that remote interventions will continue to play a key role in the delivery of essential services to PWID.

Read full COVID-19 impact section below.

Introduction

Drug use in the UK is the highest reported of any country in Western Europe; 1 in 11 people aged 16 to 59 years report having used an illicit drug in the last year in England and Wales and 1 in 14 in Scotland (1 to 4). It is estimated that over 300,000 people aged 15 to 64 in England use opioids or crack cocaine, of which approximately 87,000 people inject drugs (5, 6).

PWID are vulnerable to a wide range of health harms which can result in high levels of morbidity and mortality, including blood-borne viral infections, bacterial infections and overdose. HIV, HBV and HCV are effectively transmitted through the sharing of needles, syringes and other injecting equipment. Unsterile injection practices are also associated with bacterial infections such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as Group A Streptococcus (GAS), which are often worsened by poor wound care and delays in seeking healthcare. PWID are at risk of rare but life-threatening infections with spore-forming bacteria such as tetanus, botulism and anthrax, which can be associated with contaminated drugs and poor injecting technique. Infection and other injecting-related harms among PWID are amplified by the existence of structural barriers to accessing prevention, care and treatment services such as homelessness, imprisonment and discrimination.

This annual national report and its accompanying data tables describe infections and other injecting-related harms alongside associated risks and behaviours among PWID in the UK to the end of 2021 (7). As in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic response continued to impact access to services for PWID in 2021, including BBV testing, treatment and harm reduction. The full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting restricted access to services on the health and wellbeing of PWID in the UK remains to be seen (8, 9). Continued public health monitoring of infectious diseases and other drug-related harms among PWID is critical to understanding the impact of COVID-19 on national HIV and viral hepatitis elimination efforts, as well as on the health inequalities experienced by this marginalised group.

It is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic response also had an adverse impact on surveillance data collection and reporting in both 2020 and 2021. In addition, it has limited recruitment to bio-behavioural surveys among PWID, including the Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring (UAM) Survey in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and the Needle Exchange Surveillance Initiative (NESI) survey in Scotland. The limitations of the data is described within the text where relevant. More details can be found in Appendix 1 – Data sources.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)

Chronic hepatitis C prevalence continues to decline, but prevention of new and re-infections remains a challenge.

In 2016, the UK signed up to the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, committing to an 80% reduction in incidence of HCV infection and a 65% reduction in mortality from HCV by 2030 (10). More recently, interim guidance has been published setting out absolute impact targets for viral hepatitis elimination, aiming for HCV incidence rates of 5 new infections or fewer per 100,000 population (2 infections or fewer per 100 PWID) and 2 or fewer deaths per 100,000 population for HCV-related mortality (11, 12). Strategies across the UK that aim to eliminate HCV as a public health threat include:

- finding and treating those who remain undiagnosed

- improving access to, uptake of, and engagement with HCV treatment

- ensuring provision of adequate harm reduction to prevent new and re-infections (13, 14)

HCV prevalence

Injecting drug use continues to be the most important risk factor for HCV infection in the UK, being cited as a risk in more than 90% of all laboratory reports where risk factors have been disclosed (Data table 1a) (13, 15).

The proportion of UAM Survey participants in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (EWNI) with evidence of ever being infected with HCV (antibodies to HCV infection) has increased over time from 47% in 2012 to 57% in 2021 (Data Table 1b) (16, 17). HCV antibody prevalence in Scotland has not changed substantially in recent years and was 55% in the most recent NESI survey (2019 to 2020) (Data Table 1b).

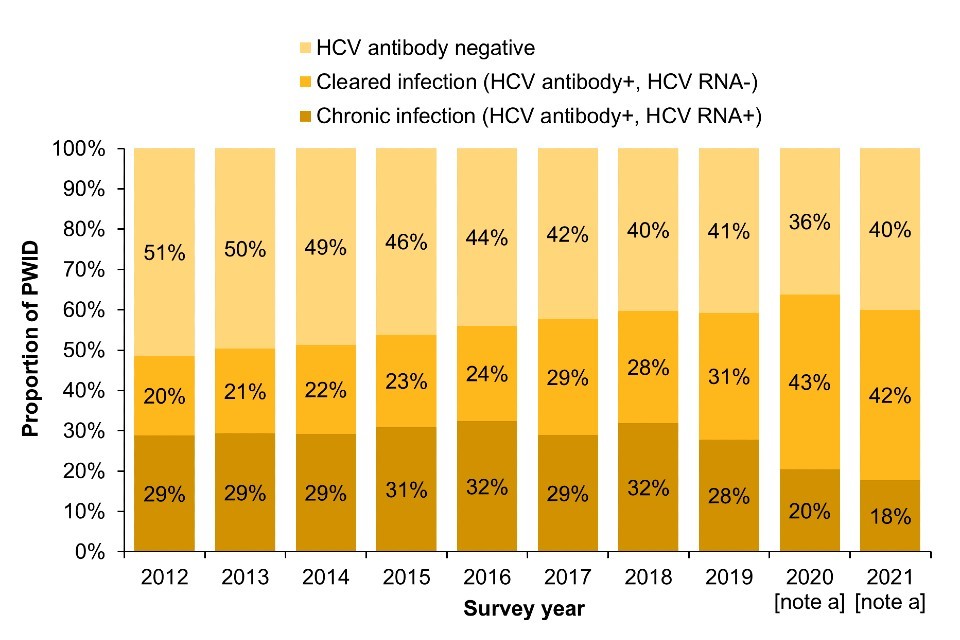

People are considered to have chronic HCV infection if they test positive for HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) in addition to HCV antibodies. In EWNI, there has been a decline in the prevalence of chronic HCV infection in recent years. (Figure 1a; Data Table 1b) (16, 17). In 2021, 18% of people who injected drugs in the past year had a chronic HCV infection. Correspondingly, the prevalence of cleared HCV infection has increased in recent years, and was 42% in 2021 (Figure 1a).

When stratified by nation, a sharp increase in chronic HCV prevalence was observed in Northern Ireland in 2020 and 2021 combined, likely reflective of an ongoing outbreak in the country (18). UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has worked alongside the Public Health Agency Northern Ireland to support case finding and outbreak monitoring through the use of whole genome sequencing (Focus topic 1).

Figure 1. Trends in chronic and cleared HCV prevalence among people who injected drugs in the last year: UK, 2012 to 2021

(a) England, Wales and Northern Ireland

(b) Scotland

Footnotes for Figure 1

Data is shown for those years where there is HCV RNA testing data available. Estimates for chronic and cleared HCV infection have been adjusted to take into account antibody-positive samples with missing HCV RNA status. The ratio of chronic to cleared infection was applied to the antibody-positive samples with missing HCV RNA status by year and by geography (English regions, Wales, Northern Ireland for UAM Survey, NHS health board Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Tayside and the rest of Scotland for NESI survey).

Note a: During 2020 and 2021, recruitment to the UAM Survey was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result there were changes in the geographic and demographic profile of those taking part. This should be taken into account when interpreting data for these years (16).

Note b: The 2019 to 2020 NESI survey was suspended before completion due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data sources for Figure 1: Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring Survey of People Who Inject Drugs (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) and Needle Exchange Surveillance Initiative (Scotland).

Focus topic 1. Public health application of whole genome sequencing for identifying and responding to an outbreak of hepatitis C among PWID in Northern Ireland

All HCV RNA positive samples in Northern Ireland are sent to UKHSA’s Antiviral Unit for whole genome sequencing, which gives unique population level coverage of sequencing. The sequencing pipeline is offered as a UKAS-accredited clinical service to inform patient management, providing the HCV genotype, subtype and pattern of resistance mutations in the NS3, NS5A and NS5B genes in a single test agnostic to viral subtype. As part of quality control procedures to assess for contamination within the sequencing pipeline, phylogenetic trees – which evaluate the relatedness of viral sequences – are routinely generated for the current sequencing run plus the preceding 5 runs for 7 regions across the HCV genome. Through this process, a cluster of 25 closely related genotype 1a HCV infections from Northern Ireland was identified in July 2020, and alerted to the Public Health Agency (PHA) Northern Ireland.

This triggered an incident management team being set up to investigate locally. Epidemiological investigation revealed that the cases were focused in Belfast city centre, and predominantly in young adults who inject drugs and were experiencing homelessness, and/or the criminal justice system. New trends in injecting drug use had emerged, with powder cocaine being the most commonly injected drug instead of heroin, and people injecting multiple times per day.

The sequencing results enabled the PHA Northern Ireland and UKHSA to clearly identify that this was a true outbreak of infection, and have permitted ongoing monitoring of the outbreak. The latest sequencing results in June 2022 identified one large genotype 1a cluster of 141 sequences, and 3 smaller 1a clusters, two 3a clusters and one 2b cluster within Northern Ireland. The PHA Northern Ireland and UKHSA and are now looking into the application of the HCV sequence data in analysing re-infections and understanding further the timing and geography of the outbreak.

HCV transmission clusters were identified by sequencing in Northern Ireland due to the high level population sequencing coverage. This coverage is lacking for other parts of the UK, which reduces the possibility of early outbreak detection. UKHSA is currently establishing a national genomics surveillance programme for England, which seeks to use leftover blood samples collected as part of routine care in patients with HCV infection, for whole genome sequencing. Results will be linked to the HCV Treatment Registry and outputs will support early outbreak detection, particularly among key populations such as people who inject drugs, as well as monitoring of circulating strains and prevalence of antiviral drug resistance, in support of the HCV elimination program.

In Scotland, the prevalence of chronic HCV infection among people who reported injecting drugs in the past year fell from 39% in the 2015 to 2016 NESI survey to 19% in the 2019 to 2020 survey. The prevalence of cleared HCV infection increased from 19% to 36%, respectively (Figure 1b; Data Table 1b).

When considered together with the increase in HCV antibody prevalence, the fall in chronic prevalence among PWID in the UK overall is likely to be due to better uptake of HCV treatment rather than improved prevention of new infections through harm reduction initiatives (15, 19, 20). To achieve and sustain elimination, community scale-up of HCV treatment needs to be combined with improvements in harm reduction coverage and retention (13). Understanding where the impact of HCV infection is greatest can help to identify where focused action is needed (Focus topic 2).

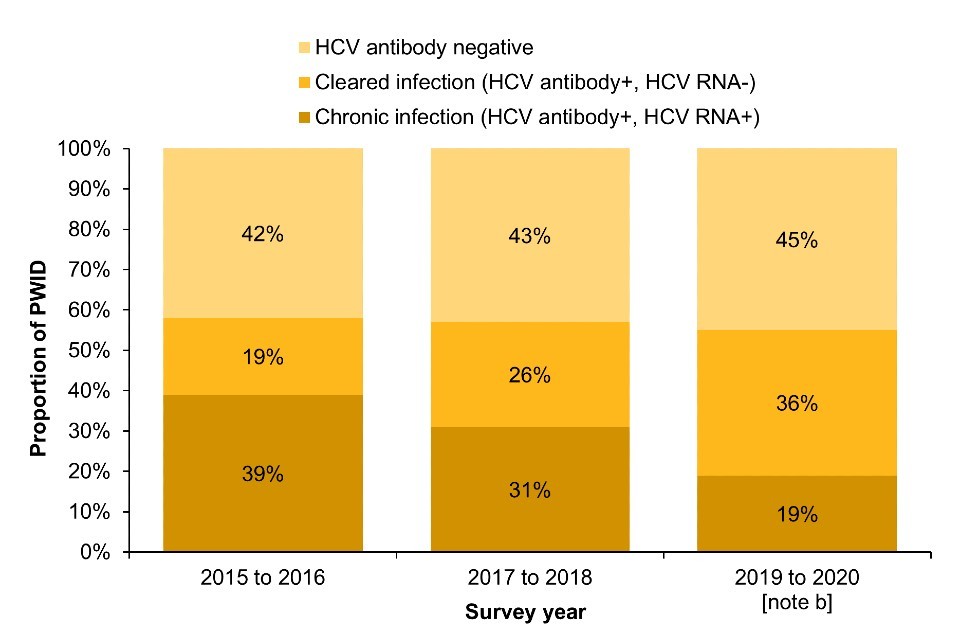

Focus topic 2. Chronic hepatitis C prevalence among PWID by risk group

Data on chronic HCV prevalence can be stratified by selected characteristics and reported behaviours to better understand where the impact of infection is greatest (Figure 2). This data could help to identify where targeted action is needed to eliminate HCV as a public health threat.

A decline in chronic HCV prevalence can be seen across most risk groups after 2018, which is in line is with the scale-up of effective HCV treatment through community drug services from 2017 onwards (7, 20, 21). However, the prevalence of chronic HCV infection varies considerably across these groups. During 2021, when compared with chronic HCV prevalence among PWID overall (14%), prevalence was higher among people who reported stimulant injection in the past year (20%), homelessness in the past year (19%), injecting any drug in the past year (18%) and ever imprisonment (17%). There was a sharp increase in chronic HCV prevalence among recent initiates to injecting in 2018, followed by a decline. However, chronic HCV prevalence in 2020 and 2021 combined in this group was similar to that seen a decade ago. There is greater uncertainty surrounding the estimates in recent initiates, due to the small (and declining) number of people in this group within the sample.

This data suggests that there are certain risk groups, in particular people experiencing homelessness and people who report stimulant injection in the past year, where targeted action would be helpful to ensure continued reductions in HCV prevalence. Targeted information on HCV, more accessible harm reduction, as well as improvements in diagnostic testing (including re-testing) and linkage to care among these groups will be important to prevent new and re-infections.

Figure 2: Chronic hepatitis C prevalence among PWID by risk group, 2012 to 2021 [note a], England, Wales, and Northern Ireland

Footnotes for Figure 2

Note a: During 2020 and 2021, recruitment to the UAM Survey was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, there were changes in the geographic and demographic profile of those taking part. This should be considered when interpreting data for these years (16).

Note b: Recent initiates to injecting are those who commenced injecting within the last 3 years. Data for recent initiates are presented for the years 2020 and 2021 combined due to small numbers.

Data source for Figure 2: Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring Survey of People Who Inject Drugs (England, Wales and Northern Ireland).

Surveillance data on diagnostic testing can also be used to inform estimates of HCV prevalence (Data Table 1a). Sentinel surveillance of blood-borne virus (BBV) testing in England reported an HCV antibody positivity of 23% among people tested in drug services in 2021. Of those who had an RNA test result available (95%), 29% had a chronic HCV infection. Sampling and regional variation likely explain why HCV prevalence measured through sentinel surveillance is different to that measured through the UAM Survey. In addition, the UAM Survey includes people unaware of their infection, whereas diagnostic testing likely includes a higher proportion of people with known risk factors for HCV.

In Wales, HCV antibody prevalence in the 2021 to 2022 financial year was 22% among people who had ever injected drugs tested in specialist drug services and included in the Harm Reduction Database (HRD); 20% were found to have chronic HCV infection (Data Table 1b) (22). HCV antibody prevalence has increased since 2020, but the proportion is lower than reported through the HRD in previous years. This may reflect the disruption in BBV testing within specialist substance misuse services during the pandemic (22). HCV prevalence measured through the HRD generally is lower than that measured in the UAM Survey, likely due to sampling and regional variation and because people unaware of their infection are not included in the HRD.

Among people who have ever injected drugs newly presenting for drug treatment in England in the 2021 to 2022 financial year who had been tested for HCV and were aware of their result, 41% reported they were antibody positive, and 18% reported they were currently infected with HCV (National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) (Data Table 1b)).

HCV incidence

Recent primary transmission of HCV within the past 3 months can be assessed by describing HCV RNA positivity among people negative for HCV antibodies. These individuals have markers of current infection (RNA) but are yet to mount an antibody response – individuals who have been re-infected following treatment are not included. HCV RNA testing of HCV antibody negative samples has been carried out in Scotland since the 2008 to 2009 NESI survey, and in EWNI for samples collected through the UAM Survey between 2011 and 2013, and from 2016 to 2021. This data suggests that the incidence of infection among PWID in the UK has remained relatively stable in the range of 10 to 16 per 100 person-years in the past 5 years (13). In contrast, systematic review evidence suggests that the rate of re-infection in PWID who have been successfully treated is substantially lower (23). It is important to acknowledge that reductions in chronic HCV prevalence have only been observed within the past few years. Evidence of a reduction in HCV incidence of primary infection or re-infection is more uncertain and may take longer to emerge.

As most new HCV infections are acquired through injecting drug use, the prevalence of antibodies to HCV among recent initiates to injecting drug use (that is those who began injecting up to 3 years prior to survey participation) can be used as a proxy measure of incidence. HCV antibody prevalence among recent initiates in EWNI was estimated at 27% for 2020 and 2021 combined (Data table 1b) (13). This proportion is similar to previous years and suggests that new infections continue to occur. Data from the NESI survey also suggest that the prevalence of antibodies to HCV among recent initiates in Scotland has remained relatively stable in recent years.

In England, linked national testing and treatment surveillance data was used to obtain preliminary estimates of HCV re-infection following treatment. Among people who had received HCV treatment between 2015 and 2021, the HCV re-infection rate was 10.9% among people with a history of injecting compared to 5% among people with no injecting history recorded (15). Surveillance data from Scotland have shown an increase in HCV re-infection rates among PWID who had previously been treated and achieved a sustained virological response. This increase has occurred alongside the scale-up of direct-acting antivirals, indicating the need for re-testing following treatment (24).

HCV testing

In 2021, 16% of PWID surveyed in EWNI reported increased difficulty accessing testing for viral hepatitis and/or HIV compared to 2019. This proportion is similar to that reported in 2020, indicating that the COVID-19 pandemic response has continued to affect access to essential services in 2021. Expanded community outreach testing and linkage to care through peer support can help to reach underserved groups and those not in contact with services (Focus topic 3). Such models of service delivery are key to achieving and sustaining HCV elimination, particularly in the wake of the pandemic.

Focus topic 3. The role of peer-led engagement and support in hepatitis C testing and linkage to care

Most people who have HCV in England are poorly reached by health services and experience significant health inequalities. In order to address this, England’s approach to HCV elimination includes significant involvement (including leadership) from people with lived experience of hepatitis C. Within this, the Hepatitis C Trust (HCT) leads a large, national programme which aims to increase HCV awareness, testing, diagnosis and treatment through peer education and support.

HCT Peer teams engage and diagnose people from marginalised populations, in particular people who inject drugs, people experiencing homelessness, and people with experience of the criminal justice system.

The model provides local, peer-led awareness and support, as well as service development. The Peer teams work closely with local health and substance use services, including community pharmacies, and with prisons. They provide training to health and care staff on hepatitis C, and work as part of local NHS systems to improve services, and to make testing and treatment more accessible. Peers also deliver testing directly and facilitate community treatment. The model includes community outreach, for instance engaging with hostels, day centres and other services for people experiencing homelessness. A peer-supported self-testing service is also available in some areas, giving people the option to self-test at home. The self-testing model helps to overcome barriers in service access and provision.

HCT peers began working in prisons and communities in 2019. By April 2022, Peer teams had engaged more than 100,000 people: 50,660 in communities and 52,135 in English prisons, and tested more than 35,000 (18,467 in communities and 17,691 in prisons). More than 15,000 staff have also been trained in hepatitis C awareness in health, care and prison settings, and the teams have received more than 6,500 referrals for peer support.

This large-scale, national programme bears out emerging evidence on the potential for peer-based models, particularly in tackling health inequalities. Links across the peers and with partners generate innovation, rapid sharing of good practice and excellent reach.

This model is now being expanded to engage people in new settings such as accident and emergency (A&E), and to engage and screen marginalised groups at risk of other liver disease and cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma).

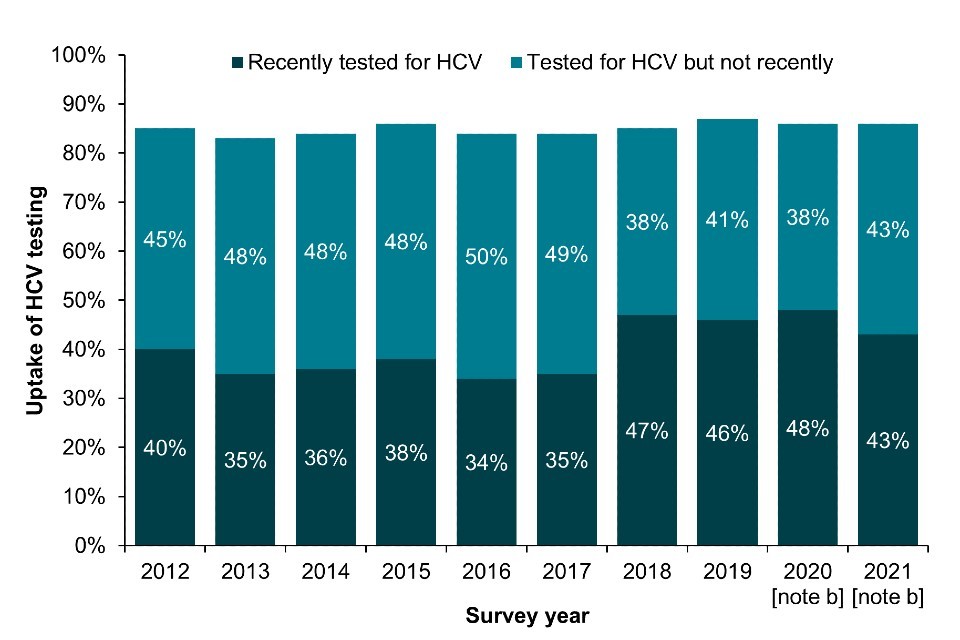

Sentinel surveillance of BBV testing in England show that the number of people who received HCV antibody testing in drug services in 2021 has shown some recovery towards pre-pandemic levels, although fewer people were tested than in 2019 (23,931 in 2021 compared to 25,912 in 2019). The number of people who received HCV RNA testing also remains lower than in 2019 (1,526 in 2021 compared to 2,027 in 2019) (Data Table 1a) (5).

In Scotland, data from sentinel surveillance of HCV testing in 4 NHS boards show a partial recovery in the number of people tested for HCV in prisons and drug services in 2021, but the number of people tested was 29% and 43% lower compared to 2019, respectively (25).

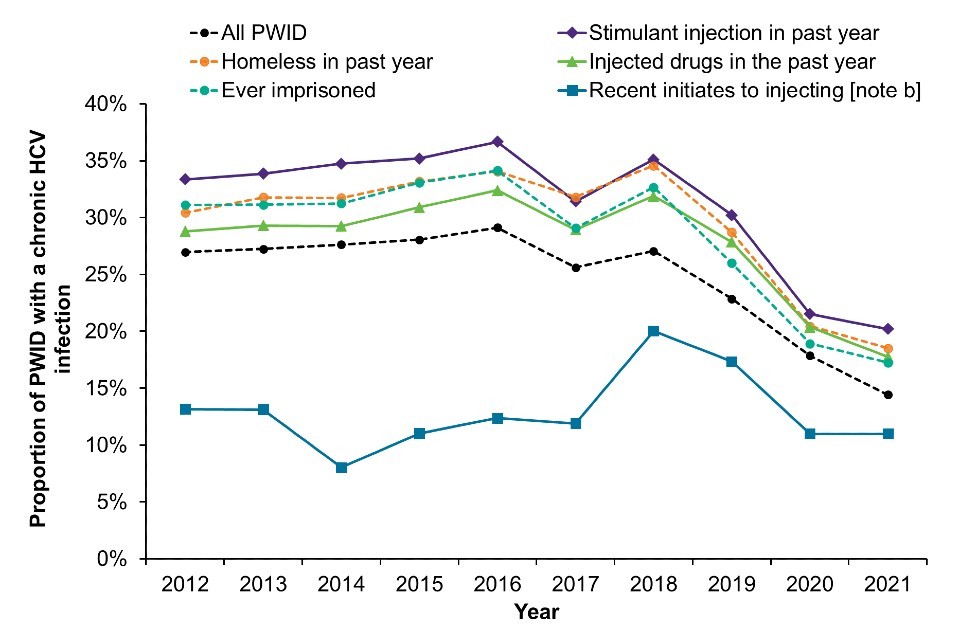

Bio-behavioural survey data shows the proportion of PWID who reported ever being tested for HCV has remained relatively stable in EWNI over the last decade. Self-reported uptake of ever testing for HCV was 86% in 2021, with 43% reporting testing in the current or previous year (Figure 3a; Data Table 6b) (16, 17). The proportion reporting a recent test has fallen slightly in the past year in England and more so in Wales, which likely reflects the disruption in service provision and BBV testing during the pandemic (Focus topic 4) (22). On the other hand, there was a sharp increase in recent HCV test uptake in Northern Ireland in 2020 and 2021 combined due to the ongoing outbreak (18).

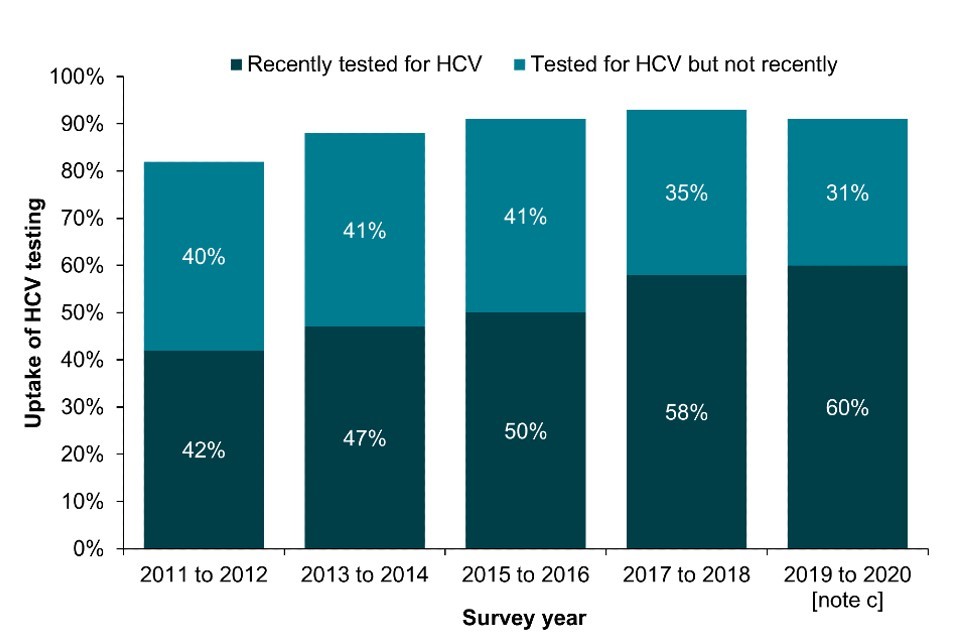

In Scotland, the proportion of people who injected in the last 6 months who reported ever testing for HCV increased from 82% in NESI 2011 to 2012 to 91% in 2019 to 2020 (pre-COVID-19) (Figure 3b; Data Table 6b). The proportion reporting testing in the last year also increased from 42% in 2011 to 2012 to 60% in 2019 to 2020 (Figure 3b; Data Table 6b).

NDTMS data shows that among people who have ever injected drugs newly presenting for drug treatment in England, the proportion who had been offered and accepted an HCV test was 71% in the 2021 to 2022 financial year (Data Table 6b).

Figure 3. Uptake of HCV testing among people who have ever injected drugs in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and people who injected in the last 6 months in Scotland, 2011 to 2021

(a) England, Wales and Northern Ireland

(b) Scotland

Footnotes for Figure 3

Note a: A recent test is defined as reporting testing in the current or previous year (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) and in the last 12 months (Scotland).

Note b: During 2020 and 2021, recruitment to the UAM Survey was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result there were changes in the geographic and demographic profile of those taking part. This should be taken into account when interpreting data for these years (16).

Note c: As the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey was suspended before completion due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data sources for Figure 3: Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring Survey of People Who Inject Drugs (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) and Needle Exchange Surveillance Initiative (Scotland).

Focus topic 4. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic response on BBV testing in specialist substance misuse services across Wales

In Wales, service access and laboratory capacity for BBV testing, primarily dried blood spot tests (DBST), was severely limited due to prioritisation of COVID-19 testing, particularly between April and December 2020. DBST are the central mechanism for routine opt-out testing in specialist substance misuse and allied services in Wales, including homeless hostels and supported housing.

Prior to March 2020 in Wales, routine opt-out testing among people who inject drugs (current or ever) had been prioritised following additional investment and the introduction of a BBV testing Key Performance Indicator in services, resulting in a 34% increase in testing in the 2019 to 2020 financial year, compared to the previous year. However, as a consequence of COVID-19 restrictions in service access and laboratory capacity, DBST testing reduced by 79% in the 2020 to 2021 financial year and remained at 52% of pre-pandemic testing levels in the 2021 to 2022 financial year. While DBST rates are increasing, they have still not achieved pre-pandemic levels, with clear implications for risk of undiagnosed infection, onward transmission and challenges to the achievement of elimination.

Awareness of HCV infection

In 2021, 30% of UAM Survey participants in EWNI with chronic HCV infection reported that they were aware of their infection status, similar to 2019 and 2020. However, there has been a significant decline in reported awareness since 2017, when 51% reported being aware (Data Table 6c) (16, 17). Diagnostic BBV testing is frequently offered by participating drug and alcohol services alongside the UAM Survey so respondents are likely to receive their results shortly after completion. Improvements to the UAM Survey are underway to address any potential bias that might result in an overestimate of the proportion unaware of their infection. Furthermore, with increased testing, access to, and engagement with treatment, the proportion of participants with chronic HCV infection who are aware of their infection status is expected to decline.

In Scotland, 49% of participants in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey (pre-COVID-19) with chronic HCV infection were aware of their infection (Data Table 6c).

HCV treatment

Among UAM Survey participants testing positive for HCV antibodies who were aware of their infection in 2021, 64% had seen a specialist nurse or hepatologist for their HCV infection and had been offered and accepted treatment. This proportion is similar to that reported in 2020 and represents a large increase from 2019 (39% accepted treatment) (16). The increase in HCV treatment uptake has been observed from 2017 onwards and corresponds with the scale-up of DAA treatment for HCV among PWID (19, 20).

In 2021, among people testing positive for HCV antibodies who were aware of their infection and had ever seen a hepatitis nurse and doctor, 13% reported that they had started HCV treatment more than once. In 2021, 86% reported they completed their most recent round of HCV treatment, and of these 74% reported a successful outcome (that they cleared HCV).

The increase in self-reported HCV treatment uptake is encouraging but ongoing monitoring and evaluation is needed to ensure support to engage with and access treatment remains equitable for all PWID living with HCV. Similar to 2020, 6.5% of PWID surveyed in EWNI who started HCV treatment prior to the COVID-19 pandemic reported some form of HCV treatment disruption in 2021, either missed doses or treatment not being available (16).

In the Scottish 2019 to 2020 NESI survey, 70% of those who self-reported as being eligible for treatment, that is, those who answered they have HCV or had cleared HCV through treatment, reported ever having received treatment for their HCV infection. This is a marked increase from 28% reported in the 2015 to 2016 NESI survey and 50% in the 2017 to 2018 survey. Of those who had ever received treatment in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey, 49% had received it in the last year (26).

Hepatitis B virus (HBV)

HBV remains rare, but vaccine uptake has declined substantially.

In addition to HCV, the WHO Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis sets out targets to reduce HBV incidence by 95% and HBV-related mortality by 65% by 2030 (10, 27).

HBV prevalence

There has been a significant decline in the proportion of UAM Survey participants with antibodies to HBV core antigen (a marker of ever infection). In 2021, prevalence had declined to 5.9%, the lowest level reported within the past decade (Data Table 2b) (16, 17). The proportion currently infected with HBV, with detectable levels of HBV surface antigen, was 0.20% in 2021 (Data Table 2b). The decline in HBV likely reflects a decline in exposure to, and transmission of, HBV over time, as a result of vaccination. However, vaccine provision to PWID was substantially reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic (28, 29), and the implications for HBV transmission are still to be determined.

HBV vaccination

HBV vaccination is recommended for all people who currently inject drugs and those who are likely to ‘progress’ to injecting, for example those who are currently smoking heroin and/or crack (30, 31). Vaccination is also recommended for all sentenced prisoners and all new inmates entering prison in the UK (31).

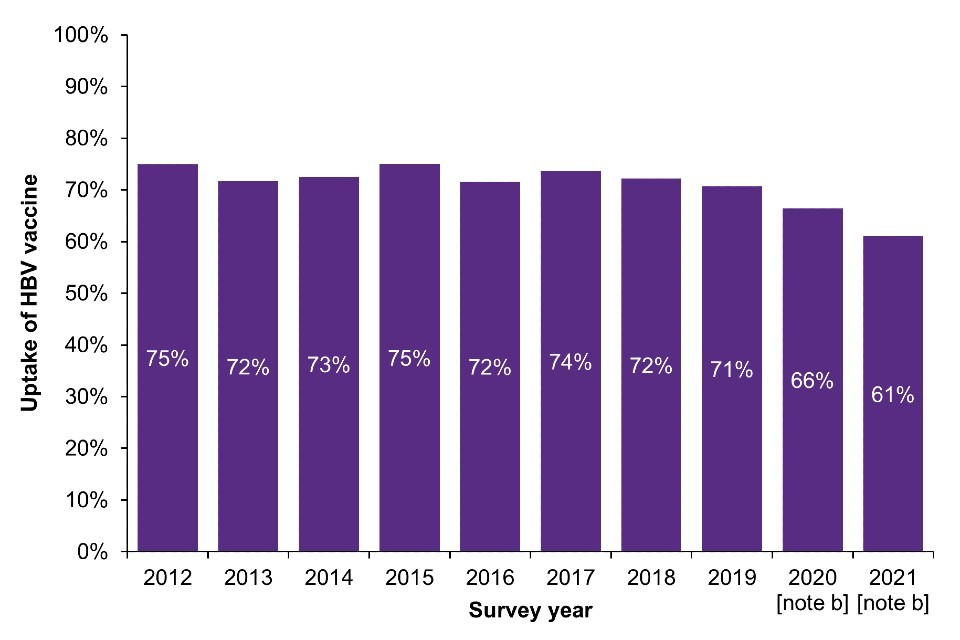

In EWNI, self-reported uptake of at least one dose of the HBV vaccine among PWID has declined over the past decade from 75% in 2012 to 61% in 2021 (Figure 4a; Data Table 6f) (16, 17). HBV vaccine uptake was particularly low among younger PWID and recent initiates to injecting during 2020 and 2021 (35% and 41% respectively) (16); UAM Survey data shows that these individuals report recent contact with services, such as general practice, prison health services and drug treatment, highlighting missed opportunities for HBV vaccination (7, 32, 33). Future studies are planned to explore the barriers and facilitators to HBV vaccination uptake to inform policy and practice. The findings will be used to support the delivery of evidence-based interventions that aim to improve vaccine coverage.

Among PWID newly presenting for drug treatment who were at risk of HBV, the proportion who were offered and accepted HBV vaccination was 39% in the 2021 to 2022 financial year (Data Table 6f, NDTMS data). This proportion was slightly lower than reported in the previous year (42%).

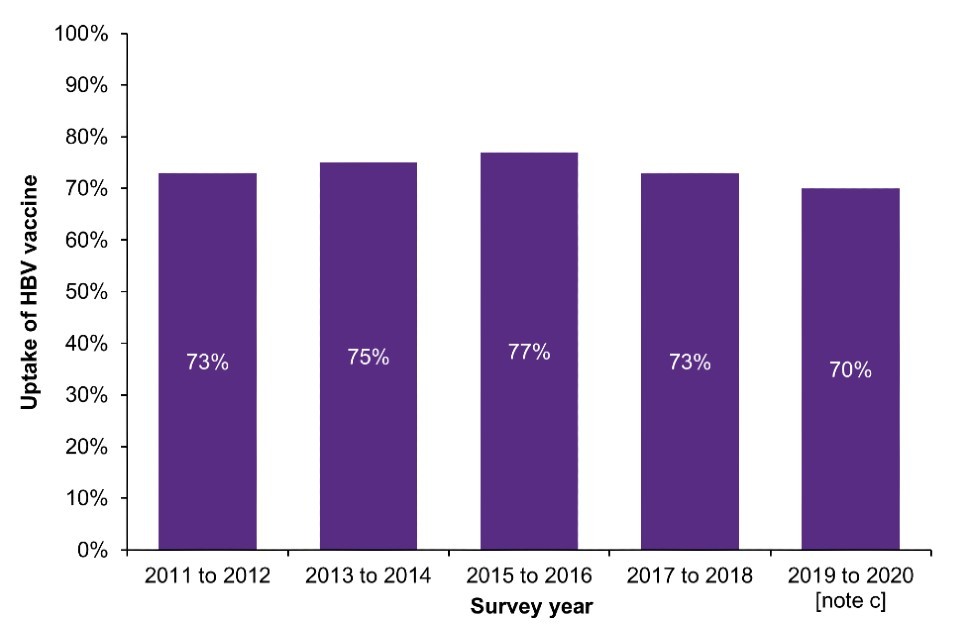

In Scotland, HBV vaccination uptake has fallen from a high of 77% in the 2015 to 2016 NESI survey to 70% in the 2019 to 2020 survey (pre-COVID-19) (Figure 4b; Data Table 6f). Prior to this decline, HBV vaccination uptake among PWID in the community had been rising steadily following the introduction of universal prison vaccination in 1999 (21).

Urgent action is required to improve vaccine uptake to ensure high levels of immunity and to maintain the low levels of reported infections. Novel strategies to improve HBV vaccination offer and uptake among PWID include local outreach initiatives that offer vaccination alongside other essential services (Focus topic 5).

Focus topic 5. Mobile HBV vaccination service in Hampshire

As part of the Harm Engagement and Reduction Team (HEART) for Inclusion Recovery Hampshire, Hepatitis B vaccination is provided by a harm reduction nurse as part of community outreach work. The service is provided in partnership with the Hampshire hepatitis C Peer 2 Peer (P2P) mentoring project and the Surrey Operational Delivery Network (ODN) outreach vans.

The outreach service enables hepatitis B vaccinations to be offered in the community at more flexible locations and times, including some evening clinics for those that work during the day. These vaccinations are offered alongside other essential services including needle exchange, provision of naloxone, blood-borne virus testing, harm reduction advice, support to access structured drug treatment, and support to address other harms associated with drug use, for instance wound care and housing.

All Inclusion Recovery Hampshire nurses are trained and competent in delivering hepatitis B vaccinations and have supported community vaccinations from the P2P van or from the service hubs (9 in total) alongside hepatitis C testing days. Hepatitis B vaccinations are delivered from the outreach vans in line with service Standard Operating Procedures and Patient Group Directives.

Figure 4. Uptake of the HBV vaccine [note a] among people who have ever injected drugs in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and in people who injected in the last 6 months in Scotland, 2011 to 2021

(a) England, Wales and Northern Ireland

b) Scotland

Footnotes for Figure 4

Note a: Reporting receiving at least one dose of HBV vaccine.

Note b: During 2020 and 2021, recruitment to the UAM Survey was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result there were changes in the geographic and demographic profile of those taking part. This should be taken into account when interpreting data for these years (16).

Note c: As the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey was suspended before completion due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data sources for Figure 4: Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring Survey of People Who Inject Drugs (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) and Needle Exchange Surveillance Initiative (Scotland).

HIV

HIV prevalence remains low and stable, but outbreaks continue.

In 2019, the government committed to end HIV transmission, AIDS diagnoses and HIV-related deaths in England by 2030 (34). The HIV Action Plan for England was published on World AIDS Day 2021, setting out the actions needed across the health system to achieve the 2030 ambition (35). The first HIV Action Plan monitoring and evaluation framework report for England was published in December 2022, and measures progress towards achieving the interim ambitions set out in the HIV Action Plan (36) (Focus topic 6).

The proposal to end HIV transmission in Scotland by 2030 was published on World AIDS Day 2022, and contains a set of recommendations to ensure progress is made towards ending HIV transmission (37). The proposal includes a recommendation to offer universal opt-out BBV testing in Scottish drug services by December 2024. This recommendation follows on from a community outbreak of HIV in the Greater Glasgow and Clyde area which started in 2015, despite relatively high coverage of harm reduction interventions (38).

Focus topic 6. HIV Action Plan for England: Monitoring and Evaluation Framework Report (36)

The interim ambitions of England’s HIV Action Plan 2022 to 2025 aim to reduce the following between 2019 (baseline data for the HIV Action Plan) and 2025:

• number of people first diagnosed with HIV in England by 80%

• number of people diagnosed with AIDS within 3 months of an HIV diagnosis by 50%

• HIV preventable deaths in England by 50%

• HIV-related stigma

The first monitoring and evaluation framework report measures progress towards achieving these interim ambitions and collates existing and potential key HIV indicators that can be used to monitor the impact of interventions, and to identify and address inequalities.

To consider all aspects of HIV prevention, including testing, diagnosis and care, a logic model was developed with 5 themes:

• maintaining people’s negative HIV status

• reducing the number of people living with HIV who are undiagnosed

• reducing the number of people with transmissible levels of virus

• managing and preventing co-morbidities and HIV-related conditions in people living with HIV

• improving quality of life and reducing stigma for people living with HIV

Each theme is accompanied by a set of indicators and their definitions. These have been drawn, where available, from existing published metrics and developed using existing data sources. These indicators are provisional and UKHSA will continue to work with key stakeholders to refine them in future reports for the HIV Action Plan monitoring and evaluation framework.

Future reports will also provide regular updates as well as data stratified by key populations, including PWID, and by geographical region. This will allow any inequalities between populations and regions to be identified and addressed. Tracking inequalities is essential to end HIV transmission since the accessibility of healthcare services differs by population, and progress overall may mask broadening inequalities for specific groups.

An interactive care pathway tool will be developed to allow local experts to track progress and inequalities. Working with and supporting populations for whom health inequalities exist and for whom services are inaccessible, will be central to ensuring progress to meeting the interim ambitions to end HIV transmission, AIDS diagnoses and HIV-related, preventable deaths.

HIV prevalence

Overall, HIV infection remains uncommon among PWID in the UK, with prevalence much lower than in many other European countries (39). In EWNI, 1.5% of PWID surveyed in 2021 were living with HIV (Data Table 3c) (16, 17). The latest data from Scotland, collected prior to COVID-19 through the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey, found HIV prevalence among those attending NSPs in Scotland and injecting in the last 6 months to be 3.8% (Data Table 3c).

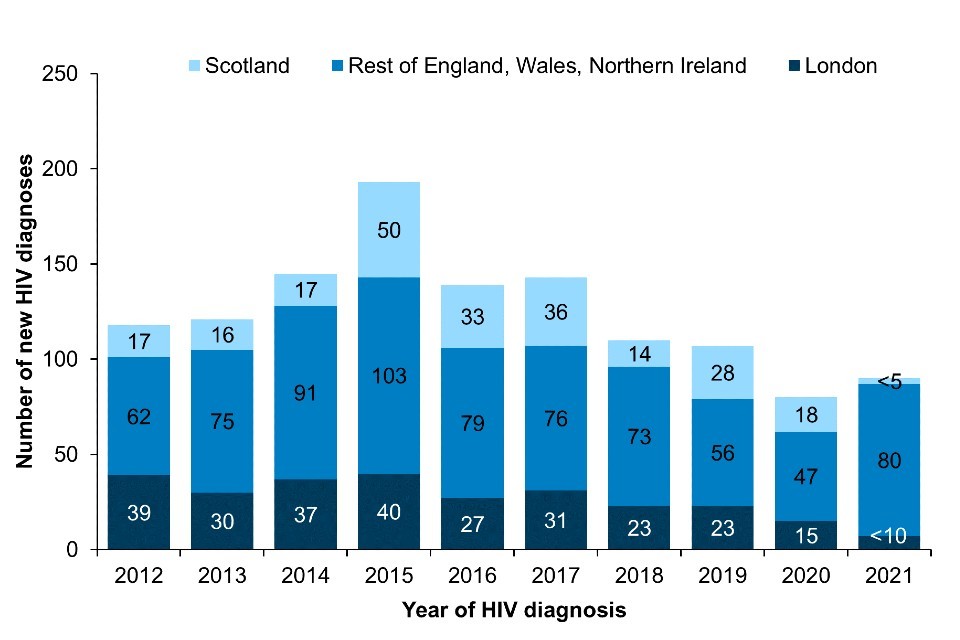

HIV diagnosis

New diagnoses acquired through injecting drug use have remained low over the past decade (Figure 5; Data Table 3a) (40, 41). In 2021, there were 90 new HIV diagnoses in the UK which were likely to have been acquired through injecting drug use. The number of new HIV diagnoses in Northern Ireland has more than doubled among PWID in the past year due to an ongoing outbreak (40, 42). New HIV diagnoses in Scotland peaked at 50 in 2015 due to the ongoing outbreak among PWID in Greater Glasgow and Clyde. Since then, new diagnoses in this group have declined annually (43). In 2021, fewer than 5 diagnoses were recorded in Scotland; however, testing among this group declined during the COVID-19 pandemic and, therefore, the number diagnosed may not reflect ongoing transmission (43).

Late HIV diagnosis (CD4 cell count less than 350 cells per µl) in the UK among people who acquired their infection through injecting drugs was 36% in 2021, compared to 40% diagnosed late overall (Data Table 3a) (40, 41).

Figure 5. New HIV diagnoses acquired through injecting drug use: UK, 2012 to 2021 [note a]

Footnotes for Figure 5

Note a: Numbers may be subject to revision due to reporting delay.

Data source for Figure 5: HIV and AIDS Reporting System, UKHSA and Public Health Scotland.

HIV testing

HIV testing continued to be disrupted in 2021 with 16% of PWID surveyed in EWNI reporting difficulties accessing testing for HIV and/or viral hepatitis compared to 2019 (9, 16). There were substantial declines in BBV testing in Wales throughout the pandemic (22).

In 2021, the majority (81%) of PWID in EWNI reported ever being tested for HIV, but only 33% reported being tested in the current or previous year (Data Table 3b) (16, 17). Missed opportunities for HIV testing and prompt diagnosis remain. In 2021, 18% of PWID who currently inject drugs reported never being tested for HIV, and a further 47% reported not being tested in the last 2 years, despite having been in contact with a range of health services in the previous year. Of those who reported that they had never tested for HIV, or who had not tested in the past 2 years, 22% reported a HCV test in the past 2 years.

In Scotland, 86% of people who had injected drugs in the last 6 months reported ever being tested for HIV in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey (Data Table 6d). Testing declined among this population during the COVID-19 pandemic (43).

The proportion of UAM Survey participants across EWNI who were unaware of their HIV infection was 19% in 2021, the highest proportion reported since 2015 (Data Table 6e). In Scotland, 58% of participants in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey reported that they were unaware of their HIV infection (Data Table 6e).

National estimates of the number of people living with HIV in the UK, including those undiagnosed, are obtained from a multi-parameter evidence synthesis (MPES) model, which is fitted to census, surveillance and survey-type prevalence data (44, 45). Although the majority of the 2,401 PWID (95% credible interval: 2,170 to 3,004) estimated to be living with HIV in the UK in 2021 were diagnosed and aware of their infection, an estimated 8% (95% credible interval: 1% to 26%) were living with undiagnosed HIV. Overall, 5% (credible interval: 4% to 6%) of all people living with HIV were unaware of their infection in 2021 (36).

HIV care and treatment

Access to HIV care services continued to be affected during 2021 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic response (41). There were 1,398 PWID accessing NHS HIV outpatient services in EWNI in 2021 (Data Table 3b). The number accessing care was similar to 2020, and represents a 4% drop from 1,457 PWID accessing HIV services in EWNI in 2019. Among PWID accessing HIV care in 2021, antiretroviral therapy coverage and viral suppression (less than 200 copies per ml) were high at 97% and 94% respectively.

Bacterial infections

Preventable bacterial infections remain a problem.

Serious bacterial infections among PWID in the UK increased between 2013 and 2019 (Data Table 4). The reasons for the rise in injection site infections during this time are not clear and are likely to be multifactorial. Barriers associated with homelessness, such as a lack of access to safe and hygienic injecting environments and resources to support general hygiene, likely play a role. In addition, injecting into the groin and other high risk sites, as well as malnutrition and existing co-morbidities, are thought to place PWID at increased risk.

The proportion of PWID reporting homelessness in the last year has increased in EWNI over the last decade, from 32% in 2012 to 42% in 2021 (16, 17). In Scotland, the proportion of PWID who reported recent experience of homelessness has remained relatively stable and was 24% in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey (pre-COVID-19) (26).

In 2021, nearly two-fifths of people (39%) who had injected in the preceding month in EWNI reported injecting into their groin (16, 17). This proportion has remained relatively stable in recent years. In Scotland, 45% of participants in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey reported mainly injecting into their groin (26).

Reported cases of serious bacterial infections among PWID declined in 2020 (Data Table 4), coinciding with the introduction of social and physical distancing measures as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response. Some of the reduction could reflect compliance with social distancing measures, increased use of hygiene measures, as well as temporary re-housing of people experiencing homelessness in hostels, thereby resulting in fewer opportunities for exposure and transmission. However, the redeployment of health staff to the pandemic response, and other health system adaptations to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, led to a decline in the provision of, and access to, health services. These changes in the delivery of healthcare, including reduced testing, as well as delayed reporting of cases by diagnostic laboratories likely contributed to the reduction in reported cases. Over one third (36%) of PWID surveyed in EWNI in 2021 reported increased difficulty accessing healthcare services and/or medicines other than OAT, compared to 2019.

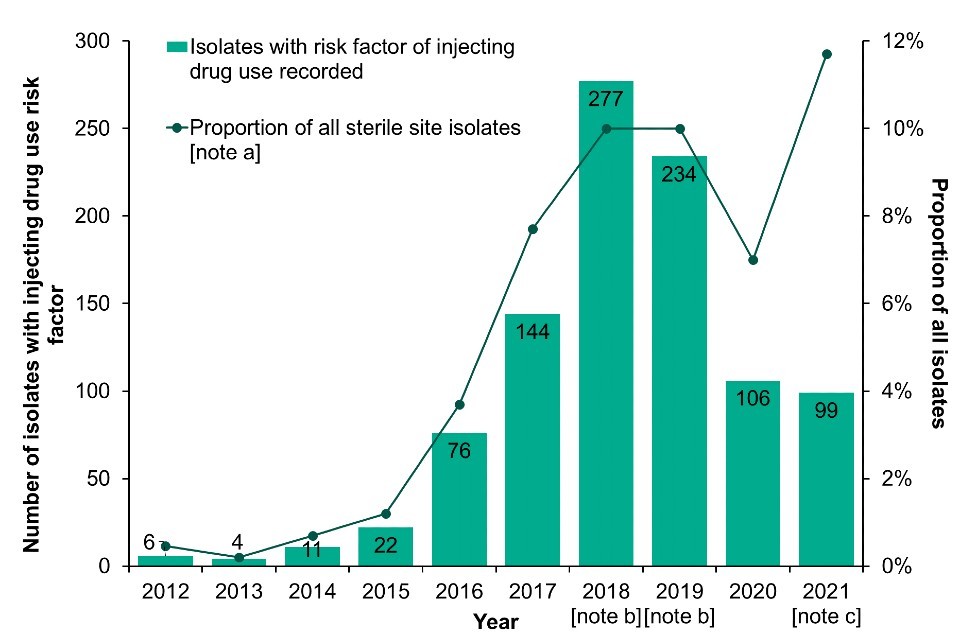

Group A Streptococcus

Invasive Group A streptococcal infection (iGAS) has been notifiable since 2010. Reports of iGAS in England and Wales indicating drug injection as a risk factor increased between 2013 and 2018 (Figure 6; Data Table 4b). Following a slight fall in cases in 2019, iGAS notifications and referrals among PWID then dramatically reduced during 2020 and 2021. Although the number of reported cases in 2021 was similar to 2020, the percentage of all reported iGAS cases associated with injecting drug use increased in 2021. There were 99 isolates of iGAS for which injecting drug use was recorded as a risk factor in 2021, representing 12% of all invasive isolates reported from England and Wales (Data Table 4b). The most common emm types identified were emm 108.1, 66.0, 33.0 and 77.0, encompassing 77% of all isolates.

In Scotland, there were 34 iGAS reports received through Public Health Scotland’s (PHS) national iGAS enhanced surveillance system in 2020 for which a risk factor of injecting drug use was indicated. This represents 21% of all cases, a proportion which has been increasing in recent years (Data Table 4b).

As a result of an increase in GAS and iGAS cases among people in prison in the UK in early 2019, specific guidance was published to support stakeholders to manage and control cases and outbreaks in this setting (46). More recently, updated guidelines have been published for the management of cases and contacts of iGAS infection in community settings (47).

Figure 6. iGAS isolates with injecting drug use recorded as a risk factor: England and Wales, 2012 to 2021

Footnotes for Figure 6

Note a: Data on infection exposure is often incomplete or missing. Proportions are calculated for those where risk is known.

Note b: Enhanced case finding occurred for 2018 and 2019 in response to the increase in reports from prisons, PWID and homeless populations.

Note c: In 2021, one iGAS isolate with a risk factor for injecting drug use indicated was reported from Wales, this equated to 11.1% of all sterile isolates reported from Wales in 2021.

Data labels refer to the number of isolates with injecting drug use as a risk factor (bars).

Data source for Figure 6: UKHSA Respiratory and Vaccine Preventable Bacteria Reference Unit and Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections.

Meticillin-sensitive and -resistant Staphylococcus aureus

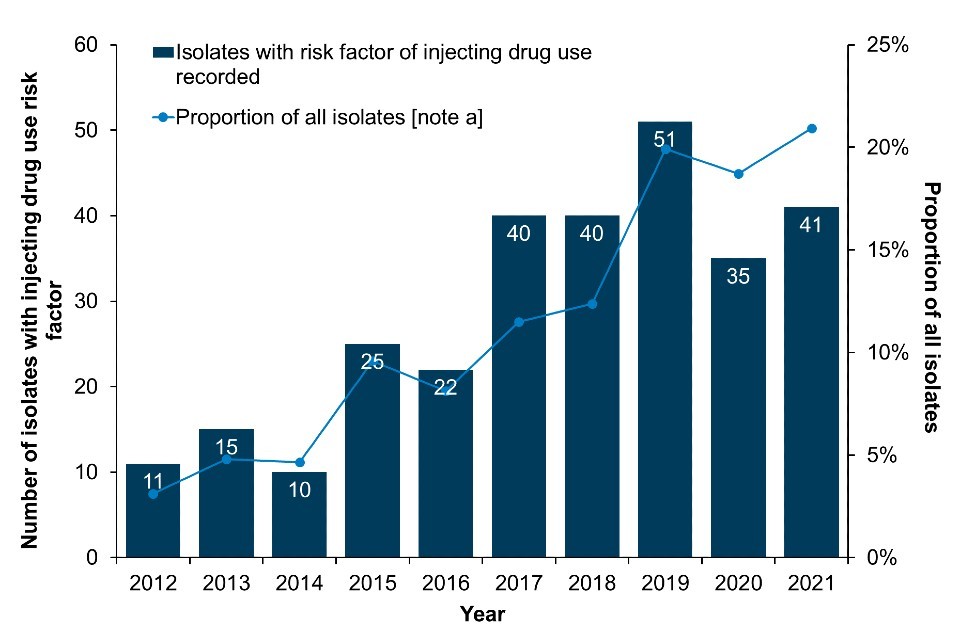

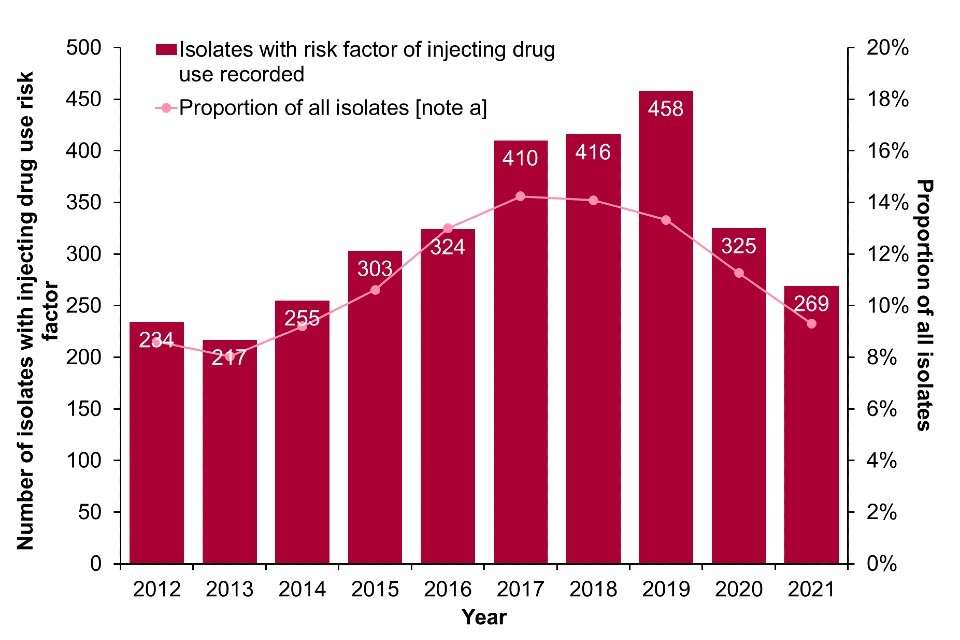

Data from the mandatory enhanced surveillance of MRSA and MSSA bacteraemias in England indicate that in 2021, there were 41 MRSA and 269 MSSA bacteraemias reported which were associated with injecting drug use, where risk information was available (Figure 7a; Figure 7b; Data Table 4c, Data Table 4d). Compared to 2020, both the number of MRSA cases and the proportion of all MRSA cases associated with injecting drug use have increased in 2021. On the other hand, MSSA case numbers and the proportion of all reported cases associated with injecting drug use have declined. It is important to note that the number of cases associated with injecting drug use for both MRSA and MSSA is likely an underestimation, as a large proportion of cases are missing information on risk factors (67% of MRSA and 74% of MSSA isolates).

In 2021, there were fewer than 5 MRSA and 88 MSSA bacteraemia cases associated with injecting drug use reported in Scotland. This represents 6.7% and 7.6% of all MRSA and MSSA bacteraemia cases reported in Scotland, respectively (Data Table 4c, Data Table 4d).

Figure 7. Reported MRSA and MSSA bacteraemias with injecting drug use indicated as a risk factor: England, 2012 to 2021

(a) MRSA

(b) MSSA

Footnote for Figure 7

Data labels refer to the number of isolates with injecting drug use as a risk factor (bars).

Note a: Data on infection exposure is often incomplete or missing. Proportions are calculated for those where risk is known. Enhanced surveillance data on injecting drug use risk-factors is missing in 67% of reported MRSA isolates between 2012 and 2021 and 74% of reported MSSA isolates between 2012 and 2021 in England and Wales.

Data source for Figure 7: UKHSA mandatory enhanced surveillance of MSSA and MRSA.

Toxin-producing bacteria (botulism, tetanus, anthrax)

The potential for cases and outbreaks of illnesses among PWID caused by the toxins produced by spore-forming bacteria, such as botulism, continues to be a concern. Spores produced by these bacteria are found in the environment and can contaminate drugs at any point in the supply chain. Although these infections are usually rare, they can be life-threatening, and there have been previous outbreaks (48). In 2021, there were 2 cases of wound botulism in PWID in the UK and one case of clinically confirmed tetanus with a history of recent drug injection. There were no cases of clinically confirmed anthrax with a history of recent drug injection in the UK in 2021 (Data Table 4a).

Symptoms of an injecting site infection

In 2021, 30% of individuals who reported injecting psychoactive drugs in the last year in EWNI reported having a sore, open wound or abscess at an injection site in the last 12 months (Data Table 4e). These symptoms are a possible indication of a bacterial skin and soft tissue infection (16, 17). The proportion reporting symptoms is lower than reported in 2020 and 2019 (38% in both years). However, there remains unmet need for easy to access wound management services in order to improve skin and soft tissue infection diagnosis and treatment before they become severe. Among PWID who reported injecting drugs in the past year and had symptoms of an injection site infection during that period, 31% reported they had hospital treatment for their symptoms. Of these, 71% reported staying overnight and 48% reported that they required surgery.

In Scotland, among people who reported injecting drugs in the past 6 months surveyed between 2019 and 2020, pre-COVID-19, 22% reported having an abscess or open wound at an injection site in the past year, down from 27% among those surveyed between 2017 and 2018 (Data Table 4e).

Injecting risk behaviours

Injecting risk behaviours have not improved.

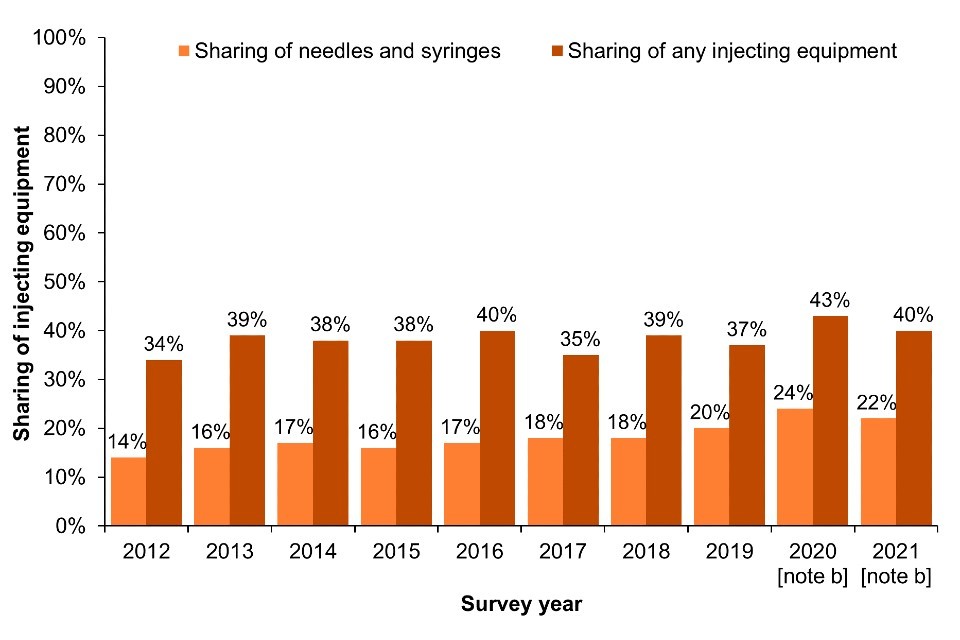

Sharing and re-use of injecting equipment

Sharing of equipment used for injecting drugs is an important contributor to BBV transmission (49, 50). During the COVID-19 pandemic, many harm reduction services, including NSPs, were reduced or suspended to redeploy staff or to facilitate social and physical distancing measures (51). Data from the UAM Survey enhanced COVID-19 questionnaire indicate that access to harm reduction services across EWNI continued to be impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, with 15% of participants reporting greater difficulties accessing equipment for the safer use and/or injection of drugs when compared to 2019 (16). Novel approaches to low threshold provision are being rolled out across the UK, including NSP provision through vending machines, or by post, as well as peer to peer distribution (28, 52) (Focus topic 7).

Across EWNI, sharing and re-use of injecting equipment remained common in 2021; 22% of UAM Survey participants who had injected drugs in the past month reported sharing of needles and syringes (‘direct’ sharing) (Figure 8a; Data Table 5b) (16, 17). Sharing of needles, syringes and other injecting paraphernalia such as filters and spoons (‘direct and indirect’ sharing) was reported by 40% of people who had injected in the last month in 2021 (Figure 8a; Data Table 5c) (16, 17).

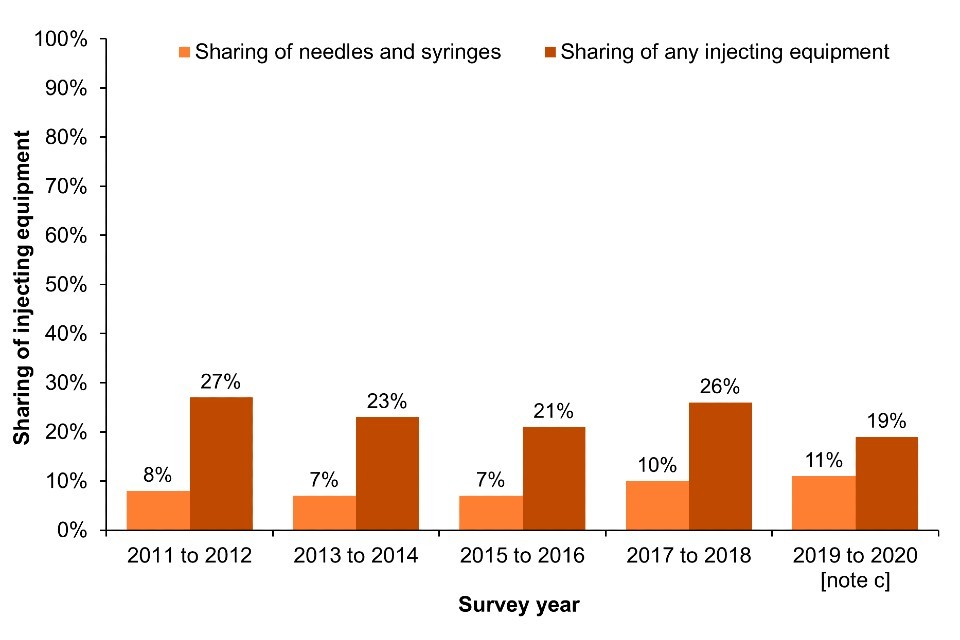

The most recent data for Scotland, collected through the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey, indicate that 11% of people who had injected in the last 6 months reported ‘direct’ sharing, and 19% reported sharing any injecting equipment, including needles, syringes, filters, spoons or water (Figure 8b; Data Table 5b and Data Table 5c). Self-reported sharing of needles and syringes in Scotland has increased slightly over the last 2 NESI survey rounds (Figure 8b; Data Table 5b). However, this data was collected pre-COVID-19.

Figure 8. Sharing of injecting equipment [note a] among people who injected drugs in the last month in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and in the last 6 months in Scotland, 2011 to 2021

(a) England, Wales and Northern Ireland

(b) Scotland

Footnotes for Figure 8

Note a: EWNI – sharing or reuse in the past month. Scotland: sharing or reuse in the last 6 months.

Note b: During 2020 and 2021, recruitment to the UAM Survey was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result there were changes in the geographic and demographic profile of those taking part. This should be taken into account when interpreting data for these years (16).

Note c: As the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey was suspended before completion due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data sources for Figure 8: Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring Survey of People Who Inject Drugs (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) and Needle Exchange Surveillance Initiative (Scotland).

Focus topic 7. Exploration of a peer-based harm reduction hub in London (52)

To reduce the harms associated with injecting drug use, Hackney Council commissioned the London Joint Working Group on Substance Use and Hepatitis C (LJWG) to scope the feasibility of developing a peer-based harm reduction hub, which would be accessible to people across London.

With funding from the ADDER Accelerate Programme (53), the scoping project included:

• focus groups with PWID and peers working in the sector

• interviews with commissioners and public health specialists

• an overview of existing international evidence on peer-based harm reduction initiatives

The project found strong support for a new harm reduction service where people could access all the equipment they need, be signposted to other services where appropriate, and receive support from peers who understand their circumstances. A strong vision emerged of a welcoming, inclusive and diverse service designed to meet the multiple complex needs of PWID, especially for those who find it hard to access or engage with traditional services.

Based on these recommendations, a service specification is now being developed for an inclusive, non-judgemental peer-based harm reduction hub. Peers with lived experience will be involved at every stage of the development and delivery of the service, with volunteer and paid positions available. The service will aim to provide a range of services including needle exchange, wound care and blood-borne virus testing, along with linkage to treatment and support for housing, benefits and mental health. The feasibility of outreach services, including an out-of-hours needle exchange vending machine and a van service, are also being explored.

If the service is approved, it will be designed as a psychologically informed environment. It will offer a welcoming space with basic comforts including warm drinks, food, bathrooms, and a space for healthcare needs. People will be able to access a full range of equipment with no quantity caps. Data collection on service use will be minimal and anonymised so that this does not act as a barrier to access, but will allow the service to evaluate impact through monitoring the number and type of equipment being taken by clients and risk of reuse.

Development of the hub is being led by a strategy group, that includes representation from both providers and commissioners, and a mirror service user group that will ensure service user insights are demonstrably shaping service delivery and outcomes. Funding for the prospective service is likely to be through a partnership between Hackney Council and NHS England, with a plan to open the service later in 2023.

In Wales, risk behaviours reported through the Harm Reduction Database have continued to increase. In the 2021 to 2022 financial year, 27% and 33% of PWID reported ever ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ sharing respectively (Data Table 5a) (22).

Re-use of one’s own injecting equipment can also put an individual at risk of infections, particularly from bacterial infections acquired through contamination when handling equipment, but also from BBVs acquired as a result of accidental sharing in situations where people store injecting equipment together (54). In EWNI, 61% of people who injected drugs in the last month reported reusing their injection equipment in the preceding 4 weeks (Data Table 5d). This proportion was slightly lower than in 2020 (64%) when data on reuse was first collected. Data from the most recent NESI survey shows the proportion reporting reuse of their own equipment in the last 6 months in Scotland has declined in recent years, from 58% in the 2017 to 2018 survey to 44% in the 2019 to 2020 survey (Data Table 5d). In Wales, 51% of individuals injecting psychoactive substances reported ever reusing injecting equipment through the HRD in the 2021 to 2022 financial year, a proportion which has remained relatively stable since 2014, when data was first collected (Data Table 5d) (22).

Adequate provision of new, sterile injecting equipment is vital to reduce sharing and reuse, as well as easily accessible information on the associated risks (55, 56). Needle and syringe provision is considered ‘adequate’ when the reported number of needles and syringes received met or exceeded the number of times the individual injected. In 2021, 66% of people who reported injecting drugs during the preceding month in EWNI had adequate needle and syringe provision (13); this is comparable to previous years. In Scotland pre-COVID-19, the proportion of people who had injected drugs in the past 6 months who reported adequate needle and syringe provision was 66% in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey (13).

Adequate needle and syringe provision may be even lower than reported above, as this data does not account for the fact that an individual may take multiple attempts to insert a needle before successfully accessing a vein, also known as achieving a ‘hit’ (57). Missed hits resulting in subcutaneous injecting are associated with injection site infections. In 2021, 58% of people in EWNI who injected in the last year reported that they needed to insert the needle more than once before getting a ‘hit’, and 19% reported that it took 4 or more attempts before achieving a ‘hit’. Identifying factors associated with inadequate needle and syringe provision can be used to inform targeted action (Focus topic 8).

Following a prolonged period of reduced funding, the opportunity now exists to improve drug treatment, infection prevention and access to harm reduction for PWID (Focus topic 9).

Focus topic 8. Characterising PWID with inadequate needle and syringe coverage (58)

People who inject drugs have variable requirements for injecting equipment. There are also structural and social barriers to accessing services, including NSP, that affect every individual differently. By identifying the characteristics of PWID who do not have adequate sterile needles and syringes to have one available for each injection attempt, we can target interventions that aim to increase availability and uptake of sterile injecting equipment.

Data from 2,442 UAM Survey participants recruited between 2017 and 2019 were analysed to identify demographic, social and behavioural characteristics among PWID who reported injecting in the last month and had inadequate needle and syringe coverage. Among people with inadequate needle and syringe coverage, a higher proportion were aged under 25 years (5.2% vs 2.4%), had initiated injecting within the past 3 years (12% vs 8.0%), and reported sharing of injecting equipment with others in the past month (41% vs 32%), compared to people with adequate needle and syringe coverage. In addition, a lower proportion reported a current prescription for OAT (68% vs 79%) compared to those with adequate coverage.

These findings suggest that younger people and people who have recently started injecting may be particularly vulnerable to the increased risk of BBVs and bacterial infections associated with needle and syringe sharing and re-use. Furthermore, there are missed opportunities for engaging this group in OAT. The findings are particularly relevant given recent increases to funding for drug and alcohol services in the UK. Targeting interventions to people with the greatest need would ensure that any additional funding and resources have maximum impact on reducing injecting-related harms.

Focus topic 9. Funding for harm reduction improvements

Following the publication of the new drug strategy in 2021 and the £780 million additional government funding allocated to support drug treatment and recovery, every local authority in England received extra funding in the 2021 to 2022 and 2022 to 2023 financial years, and will have even more to spend between 2023 and 2025 (59).

The extra funding is improving access to treatment and increasing the capacity of services to help reverse the upward trend in drug use, and in drug deaths, which disproportionately impact the most vulnerable and poorest communities. As well as improving treatment, local areas have been supported to expand and improve evidence-based harm reduction interventions, including the provision of naloxone and NSPs, as well as BBV testing, vaccination and treatment pathways.

Funding to local authorities is specific to England only, but funding for peer mentoring covers England, Wales and Scotland, and funding to support offenders includes provision of treatment through HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) in Wales. The areas relating to the work of the police and the criminal justice system apply to England and Wales. The Welsh Government, the Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Executive have their own strategies and funding to tackle the harms from drug use in areas where responsibility is devolved.

The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) and UKHSA are also working with commissioners and providers of drug treatment to pilot an introduction of national monitoring of NSPs in England so that gaps can be identified and addressed.

Sexual behaviour

PWID are also at risk of acquiring and transmitting BBVs through sexual transmission. In 2021, 56% of PWID surveyed across EWNI reported anal or vaginal sex in the last year (16, 17). This proportion was similar to 2020 (58%), and slightly lower than reported in 2019 (61%). This data indicates there was no marked change in self-reported sexual behaviour despite COVID-19 restrictions to reduce social and physical mixing.

Among people who reported anal or vaginal sex in the past year, 37% reported 2 or more sexual partners, and of those, only 17% reported always using condoms (16, 17). Among men who reported sex in the past year, the proportion who reported sex with another man during that time was 7.6%, a proportion similar to that seen in previous years. In 2021, 13% of PWID participating in the UAM Survey reported ever having traded sex for money, goods or drugs (17).

Drug use patterns

Changing patterns of psychoactive drug use remain a concern.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the drug market, causing local fluctuations in the price, purity and availability of drugs in England, especially of heroin and both crack and powder cocaine; although, overall, drug supply was maintained (28). PWID surveyed in EWNI in 2021 reported an increase in their substance use compared to 2019, with 19% injecting drugs more frequently and 26% reporting a change in their primary drug or drug combination (16).

Heroin injection

In 2021, heroin remained the most commonly injected drug in the UK, reported by 90% of people who had injected drugs in the previous month in EWNI (16). In Scotland, 89% of participants in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey who injected drugs in the past 6 months reported injecting heroin (26).

Cocaine injection

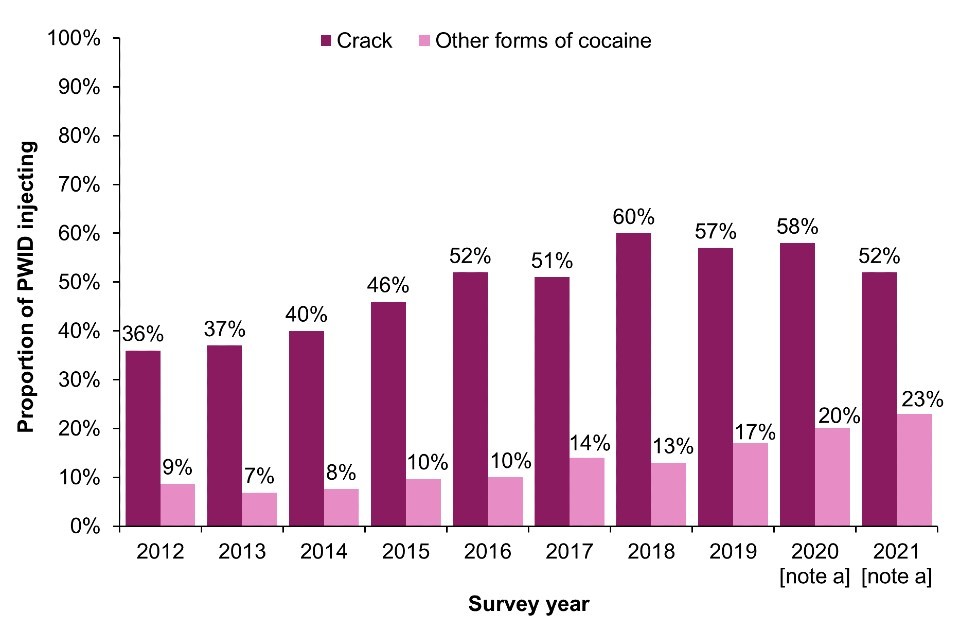

Crack cocaine injection is associated with behaviours known to increase the risk of BBVs and skin and soft tissue infections, including the sharing of injecting equipment, groin injection and higher injection frequency (60, 61). Data from the UAM Survey indicate that injection of crack remained high in 2021 in EWNI, with 52% of those who had injected in the last month reporting crack injection (Figure 9a) (16, 17). In EWNI, injection of cocaine (other than crack cocaine) has increased substantially over the last decade, with 23% of those who had injected in the last month reporting cocaine injection in 2021, compared to 8.7% in 2012 (16, 17). The increase was particularly marked in Northern Ireland over the past year, where injection of powder cocaine is thought to be driving an ongoing outbreak of HIV (16, 40, 42).

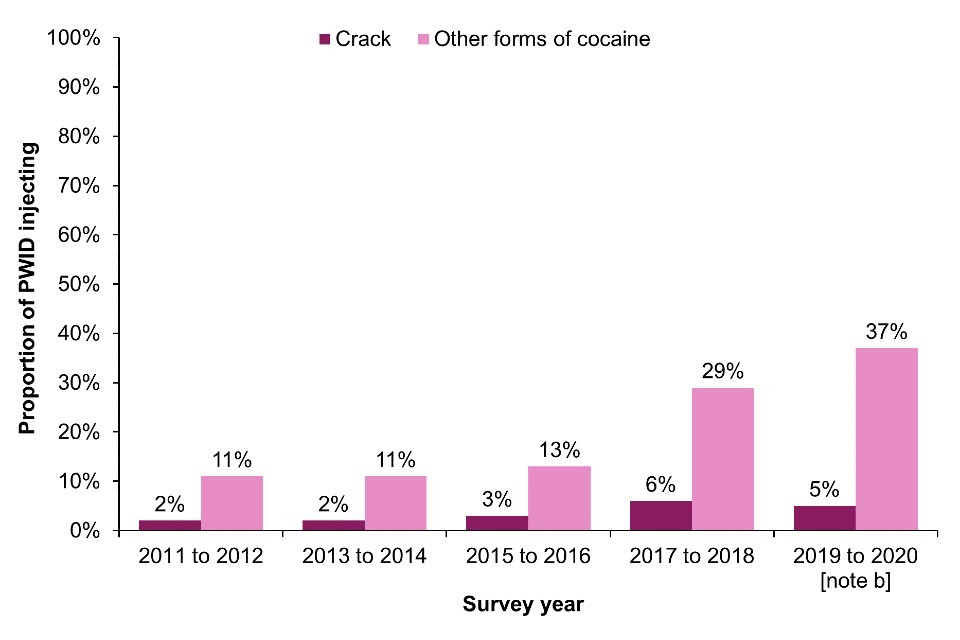

In Scotland, NESI data for 2019 to 2020 shows that injection of crack was reported by only 5.0% of those who injected in the last 6 months. Injection of powder cocaine is more common in Scotland and has increased in recent years to 37% in the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey from 11% in the 2011 to 2012 survey (Figure 9b) (26). Powder cocaine injecting was identified as an important driver in the ongoing outbreak of HIV among PWID in Greater Glasgow and Clyde (38).

Stimulant injection

The injection of amphetamine and amphetamine-type drugs among those who injected drugs in the last month continued to decline from a high of 24% in 2014 to 8.1% in 2021 in EWNI (16, 17). In Scotland, injection of amphetamines was reported by 2.5% of those who injected in the last 6 months participating in NESI 2019 to 2020 (26).

Reported injection of mephedrone has plateaued. In 2021, 2.0% of PWID surveyed in EWNI reported injecting mephedrone in the last year, which is similar to reported use in 2018. This plateau follows an overall decline in reported injection of mephedrone from 9.3% in 2014, when reported use was at its highest. Injection of mephedrone is not collected separately in Scotland but included in the ‘legal highs’ category of the NESI survey; just 0.30% of 2019 to 2020 NESI participants reported injecting drugs in this category.

Figure 9. Crack and powder cocaine injection in the last month in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and in the last 6 months in Scotland, 2011 to 2021

(a) England, Wales and Northern Ireland

(b) Scotland

Footnotes for Figure 9

Note a: During 2020 and 2021, recruitment to the UAM Survey was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result there were changes in the geographic and demographic profile of those taking part. This should be taken into account when interpreting data for these years (16).

Note b: As the 2019 to 2020 NESI survey was suspended before completion due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data sources for Figure 9: Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring Survey of People Who Inject Drugs (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) and Needle Exchange Surveillance Initiative (Scotland).

Fatal and non-fatal overdose

Rates of fatal and non-fatal overdose are at an all-time high.

Fatal overdose

In 2021, there were 4,859 deaths related to drug poisoning registered in England and Wales (84.4 deaths per million), a new record high and a 6.5% increase from 2020 (4,561) (62); 3,060 were related to substance misuse (53.2 deaths per million). In Scotland, there were 1,330 drug misuse deaths (previously referred to as drug-related deaths) (250 deaths per million), 9 fewer than in 2020. This is the first year since 2013 where there has not been an increase in deaths in Scotland, although the total number is still the second highest on record (63).

The upward trend in drug-related deaths in the UK is mainly being driven by deaths involving the use of opioids (62, 63), but the number of deaths involving other substances like cocaine is also increasing. In recent years, Scotland has recorded a large increase in the number of deaths where ‘street’ benzodiazepines (as opposed to prescribed benzodiazepines) have been implicated (63). Possible explanations for the increase in deaths in the UK involving opioids include polydrug use (for example, heroin use with benzodiazepines and/or gabapentinoids), disengagement or non-compliance with OAT, or ongoing injection of drugs alongside OAT (62). An update on the National Mission to reduce drug-related deaths and harms in Scotland is available in Focus topic 10.

Data from NDTMS shows a 0.9% increase in the number of deaths among people in contact with drug treatment services in England in the 2021 to 2022 financial year compared to the previous year (64). However, this followed a 22% increase between 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021. This includes all causes of death, and excludes any clients in alcohol-only treatment.

Focus topic 10. Update on Scotland’s National Mission to reduce drug-related deaths (DRD) and harm

The National Mission on Drugs has recently published its first annual report setting out progress made between January 2021 and March 2022 towards reducing drug deaths and improving the lives of those impacted by drugs in Scotland (65).