Spring Statement 2022 (HTML)

Published 23 March 2022

- Presented to Parliament by the Chancellor of the Exchequer by Command of Her Majesty

- Laid in Parliament on 23 March 2022

- CP 653

- © Crown copyright 2022

- ISBN 978-1-5286-3235-5

Executive Summary

Spring Statement 2022 takes place following the unprovoked, premeditated attack Vladimir Putin launched on Ukraine. The invasion has created significant uncertainty in the global economy, particularly in energy markets. The sanctions and strong response by the UK and its allies are vital in supporting the Ukrainian people, but these decisions will inevitably have an adverse effect on the UK economy and other economies too.

Higher than expected global energy and goods prices have already led to an unavoidable increase in the cost of living in the UK. The repercussions of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will add to these pressures and increase inflation further in the coming months, with the long-term consequences not yet being clear. As a result, the uncertainty surrounding the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) spring economic and fiscal forecast is higher than usual.

The UK economy has emerged from the pandemic in a strong position to meet these challenges. The success of the government’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout and the Plan for Jobs have helped support a quicker than expected recovery and a strong labour market, with the total number of payrolled employees now over 600,000 above pre-pandemic levels. Tax receipts have been stronger than expected, which has contributed to borrowing falling this year and over the forecast period. The improvement seen in the public finances has created additional headroom against the government’s fiscal rules, which the government has prioritised using to deliver reductions in tax.

The government has already taken significant steps to help with the cost of living. This includes a cut to the Universal Credit taper rate and increases to work allowances to make sure work pays; the £9 billion package announced in February to help households with rising energy bills this year; and freezing alcohol duties and fuel duty to keep costs down.

The government is taking further action in the Spring Statement to help households. A significant increase to the National Insurance Primary Threshold and Lower Profits Limit will allow hard-working people to keep more of their earned income. A temporary 12 month cut will be introduced to duty on petrol and diesel of 5p per litre, representing a saving worth around £100 for the average car driver, £200 for the average van driver, and £1500 for the average haulier, when compared with uprating fuel duty in 2022-23. To help households improve energy efficiency and keep heating bills down, the government will expand the scope of VAT relief available for energy saving materials and ensure that households having energy saving materials installed pay 0% VAT.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are also affected by rising costs. The Spring Statement builds on previously announced support for SMEs, including business rates relief worth £7 billion over the next five years; increasing the Annual Investment Allowance from £200,000 to £1 million until March 2023; subsidising the cost of high-quality training through the Help to Grow: Management scheme; and helping firms to adopt new digital technologies with Help to Grow: Digital. Businesses will also benefit from the cut to fuel duty, and the Employment Allowance will increase to £5,000 from April – a tax cut of up to £1,000 for around half a million small businesses.

The government has taken the responsible decisions needed ahead of the Spring Statement to strengthen the public finances, which has created the space to provide this extra support. The Spring Statement confirms that after providing this support the government continues to meet its fiscal rules, with an increased margin of safety. Underlying debt is falling as a percentage of GDP and the current budget is in surplus in the target year. Preserving fiscal space is vital given the increasing risks from global challenges and the level of uncertainty in the economic outlook.

Tax Plan

The Spring Statement sets out the government’s plans to reform and reduce taxes. The Tax Plan – with its focus on helping families with the cost of living, creating the conditions for private sector led growth, and sharing the proceeds of growth fairly with working people – will drive improvements in living standards and support levelling up across the UK. The Tax Plan will be delivered in a responsible and sustainable way, guided by the core principle that prudent levels of space should be maintained against the fiscal rules. It will depend on continued discipline on public spending and the broader macroeconomic outlook.

The government will reform and reduce taxes in three ways:

-

Helping families with the cost of living. The Spring Statement increases the annual National Insurance Primary Threshold and Lower Profits Limit from £9,880 to £12,570, from July 2022. This aligns the Primary Threshold and Lower Profits Limit with the income tax personal allowance. This will help almost 30 million working people, with a typical employee benefitting from a tax cut worth over £330 in the year from July.

-

Boosting productivity and growth by creating the conditions for the private sector to invest more, train more and innovate more – fostering a new culture of enterprise. To do this, the government intends to cut and reform business taxes, to create a culture of enterprise and the conditions for private sector-led growth.

-

Sharing the proceeds of growth fairly. The government will reduce the basic rate of income tax to 19% from April 2024. This is a tax cut of over £5 billion a year and represents the first cut in the basic rate of income tax in 16 years. Alongside tax cuts, the government also wants to make the tax system simpler, fairer and more efficient, and will confirm plans for reforms to reliefs and allowances ahead of 2024.

Economy and public finances

Following Putin’s unprovoked and premeditated invasion of Ukraine, cost of living pressures have intensified and uncertainty has increased. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) sets out in the Economic and Fiscal Outlook (EFO) that “given the unfolding situation in Ukraine, there is unusually high uncertainty around this outlook.”[footnote 1] Higher global energy, metals and food prices, which have been volatile since the invasion of Ukraine, pose risks to the outlook for inflation, consumer spending and production. The sanctions imposed on Russia by the UK and its allies in response to the invasion are vital in supporting the Ukrainian people. The invasion, and the resulting effect on global markets, will inevitably have an adverse effect on the UK economy and the cost of living in the short term. The medium-term implications of the invasion are highly uncertain, which increases the risks around the OBR’s forecast.

While the outlook is uncertain, the UK economy has emerged from the pandemic in a good position to meet these challenges. The success of the government’s vaccine rollout and the Plan for Jobs have helped support a quicker than expected recovery and a strong labour market.[footnote 2] Similarly, tax receipts have been higher than expected.

Elevated global energy and goods prices, following the uneven effect of the recovery from the pandemic on global supply and demand, have already led to an increase in the cost of living in the UK and some other advanced economies. The repercussions of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will add to these pressures and increase inflation further in the coming months. The independent Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has a strong track record of controlling inflation. In accordance with its remit the MPC has begun to tighten monetary policy to achieve the 2% inflation target, while supporting the government’s objective for strong, sustainable and balanced growth.

In response to pressures on the cost of living, the government announced prior to the Spring Statement a package of support to help households with energy bills and ensure that hard-working people keep more of their income. The best way to support households in the long run is through encouraging strong and sustainable growth across the UK, by promoting investment and innovation; and then sharing more of the proceeds of growth by reducing the tax burden for working people. The government is taking further action to support households through the Spring Statement by cutting taxes.

The government remains fully committed to ensuring the sustainability of the public finances. It will continue to take a responsible and balanced approach to supporting households and the UK economy, while still meeting its fiscal objectives and maintaining fiscal space to ensure the UK is resilient to future challenges. The OBR forecasts that the government will continue to meet its fiscal rules. Underlying debt (public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England) is falling and the current budget is in surplus in the target year.

Economic context

Growth and the labour market

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has created further uncertainty for the economic outlook despite the strong performance of the economy last year. While the OBR’s forecast takes account of changes in international energy prices since the invasion, significant day to day volatility in oil, gas and commodity markets has continued to create uncertainty. As the OBR highlights in the EFO, “Given the evolving situation in the war in Ukraine and the global response, there is significant uncertainty around the outlook for global Gross Domestic Product (GDP).”[footnote 3]

Following the emergence of the Omicron variant in December, the government implemented Plan B in England, and restrictions were tightened in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. This weighed on output, although by less than expected, with GDP falling by 0.2% in December 2021 before growing by 0.8% in January 2022, above expectations.[footnote 4]

The economic recovery over the past year has surpassed expectations, with GDP growth of 7.5% in 2021, the fastest in the G7. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) praised the UK’s “strong policy measures and rapid vaccination campaign that helped contain the health, economic, and financial impact of the pandemic, which supported a faster than expected recovery.”[footnote 5]

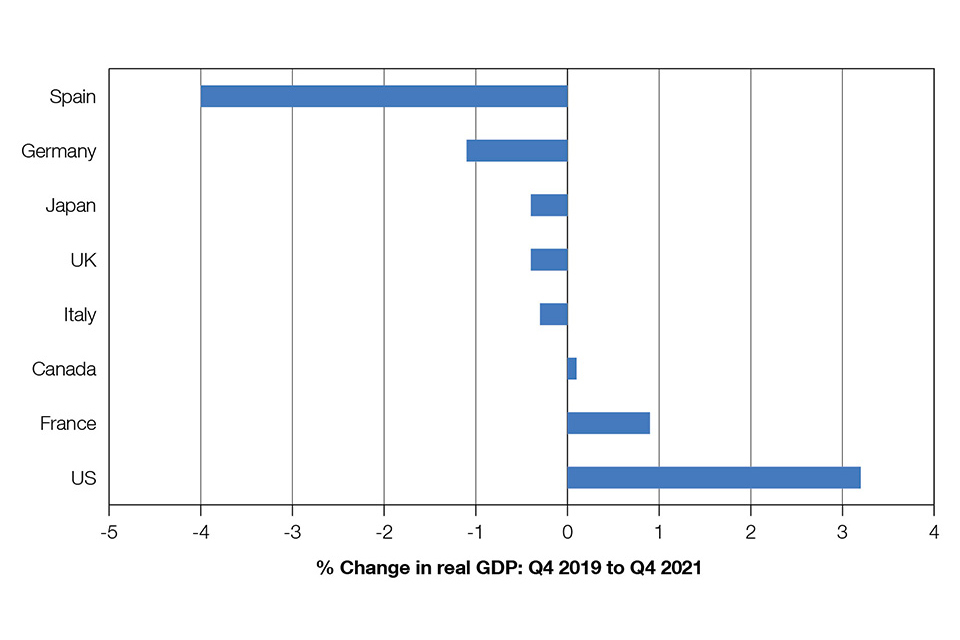

The UK economy recovered to its pre-pandemic level around the end of last year with real GDP having regained its February 2020 level by November 2021. Across the final quarter of 2021, GDP was on average 0.4% below its pre-pandemic size. This was a smaller shortfall than Germany, and broadly in line with Italy and Japan.

Chart 1.1: Quarterly real GDP shortfall to pre-pandemic levels: G7 nations and Spain

Chart 1.1: Quarterly real GDP shortfall to pre-pandemic levels: G7 nations and Spain

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Taking into account the pace of the economic recovery to date, continued global supply chain pressures and the initial impact of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the OBR expects UK real GDP to grow by 3.8% in 2022. GDP is then forecast to grow by 1.8% in 2023, 2.1% in 2024, 1.8% in 2025 and 1.7% in 2026.

Table 1.1: Summary of the OBR’s central economic forecast (percentage change on year earlier, unless otherwise stated)1

| Forecast | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | |

| GDP growth | 7.5 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| GDP growth per capita | 7.4 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Main components of GDP | ||||||

| Household consumption(2) | 6.1 | 5.4 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| General government consumption | 14.5 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| Fixed investment | 5.3 | 6.0 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 3.2 |

| Business investment | -0.7 | 10.6 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 4.5 |

| General government investment | 11.9 | -1.1 | 7.8 | -2.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| Private dwellings investment(3) | 12.6 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Change in inventories4 | 0.6 | -0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Net trade(4) | -1.2 | -0.6 | -0.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | -0.1 |

| Consumer Prices Index inflation | 2.6 | 7.4 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Employment (millions) | 32.4 | 32.7 | 32.9 | 33.1 | 33.2 | 33.3 |

| Unemployment (% rate) | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

| Productivity: output per hour | 1.2 | -0.2 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| 1 All figures in this table are rounded to the nearest decimal place. This is not intended to convey a degree of unwarranted accuracy. Components may not sum to total due to rounding and the statistical discrepancy. |

| 2 Includes households and non-profit institutions serving households. |

| 3 Includes transfer costs of non-produced assets. |

| 4 Contribution to GDP growth, percentage points. |

| Source: Office for National Statistics and Office for Budget Responsibility. |

The Plan for Jobs has supported the strong recovery in the labour market, with the total number of payrolled employees in February 2022 2.3% above pre-pandemic levels. Unemployment has fallen steadily for twelve consecutive months to below its pre-pandemic rate (three months to February 2020) at 3.9% in the three months to January 2022. The OBR highlights that the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme “looks to have exceeded all predictions, including ours, regarding its likely success in avoiding the persistent high unemployment that has followed other recessions.”[footnote 6] With vacancies at record highs, the unemployment to vacancy ratio is at a record low. Nominal wage growth was 4.8% in the three months to January 2022 and the OBR expects nominal wage growth to average 3.3% across the forecast period.

Despite this strong recovery in the labour market, there remain 420,000 more inactive workers aged 16 to 64 in the three months to January 2022 compared to the three months to February 2020. One of the main drivers of this increase has been a rise in in those reporting ‘long-term sick’, particularly between the ages of 50 and 64. The government is committed to improving outcomes for those who are inactive because of long-term health conditions or disabilities, and has dedicated over £1.1 billion of funding over the Spending Review 2021 period to specialised disability employment support; improving opportunities into and within work. This includes £156 million targeted at extra work coaches that will enable additional work coach time for claimants of incapacity benefits.

While there are more people on payrolls than ever before, the latest figures show there are 1.3 million vacancies across the economy. There are around 1.7 million claimants in the searching for work group within Universal Credit currently without a job. The government recently launched the Way to Work campaign, which aims to move 500,000 jobseekers into work by June 2022.[footnote 7] As part of this campaign, the government is reducing the time allowed for Universal Credit claimants to search for a job in their preferred sector – from three months to a maximum of four weeks. Work is the best way for people to get on, to improve their lives and support their families. Households on Universal Credit are at least £6,000 a year better off in full-time work than out of work.[footnote 8]

Inflation and the cost of living

Consumer Prices Index (CPI) inflation has risen to a 30-year high in recent months. This has primarily been driven by global factors outside the government’s control, including continued disruption to global supply chains and higher global energy and commodity prices.

Chart 1.2: Contributions to CPI inflation

Chart 1.2: Contributions to CPI inflation

Source: Office for National Statistics.

The UK is not alone in experiencing these pressures, with other major economies also experiencing higher inflation. In the twelve months to February 2022, euro area inflation was 5.9%, and US inflation was 7.9% – the highest US inflation rate since 1982.

Global goods inflation has risen, reflecting a global mismatch between demand and supply for manufactured goods, pass-through of higher energy costs and disruption to global supply chains due to the pandemic. This has affected firms through elevated input and shipping costs, and increased delivery times. The latest survey data from firms on supplier delivery times suggest that these effects remained acute in many areas even before the invasion of Ukraine.[footnote 9]

Global energy prices were volatile even before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and remain much higher than pre-pandemic levels. Increased global demand for energy, short-term supply disruptions in major oil-exporting economies, weather patterns in Europe and Asia affecting both the supply of renewable energy and the demand for heating, and lower gas storage balances have all contributed to higher prices. As the OBR sets out in the EFO, the UK is “a net energy importer with a high dependence on gas and oil”, meaning higher energy prices have led to a deterioration in the UK’s terms of trade – the relative prices of the UK’s exports compared with its imports.[footnote 10]

Following Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, energy prices have risen further amid disruptions to the supply of Russian energy to global markets. Global oil prices rose 9.3% between the week beginning 14 February (the last full week before the invasion) and the week beginning 14 March, and UK and European wholesale gas prices increased by more than 30% over the same period. Rising global energy prices will directly affect UK inflation in the short and medium term. While the Office for Gas and Electricity Markets (OFGEM) energy price cap protects consumers from the rapid changes observed in the wholesale energy market in the short term, the rise in oil prices has already affected petrol pump prices in the UK, which are now at record highs having increased by almost 12% over the past month.[footnote 11]

Although Russia and Ukraine are not major direct trading partners of the UK, they are large exporters of commodities to global markets including wheat, aluminium, nickel (which is used in batteries) and palladium (a key component in electronics).[footnote 12] Since the invasion, prices of these commodities have been volatile and some remain materially higher, indicative of reduced supply and anticipation of potential future disruption. As such, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine risks prolonging or increasing existing supply chain pressures faced by firms, which could affect UK growth and inflation in the short term.

The OBR forecasts inflation to remain elevated through 2022 and 2023, peaking at 8.7% in Q4 2022. On an annual basis, inflation is forecast to be 7.4% in 2022, before decreasing to 4.0% in 2023 and 1.5% in 2024. Inflation is then forecast to be 1.9% in 2025 and 2.0% in 2026. However, as the OBR sets out in the EFO, there is significant uncertainty around the outlook for oil and gas prices and therefore the path of inflation over the forecast period: “If … energy prices stay at current levels beyond the middle of next year, the UK would face a larger and more persistent increase in the price level and fall in real household incomes. If prices fall more quickly than currently expected the reverse would be true.”[footnote 13]

The government’s commitment to price stability remains absolute. The Bank of England is responsible for controlling inflation and has taken decisive steps by raising interest rates to 0.75%. The Chancellor re-affirmed the Bank’s 2% CPI inflation target at Autumn Budget 2021, and the government remains committed to the independent monetary policy framework which has seen inflation average around 2% between 1997 and 2019.

Nonetheless, the government recognises the effect higher inflation has on households, and has already introduced a package of support to help with rising energy bills and to allow hard-working people to keep more of their income. In the Spring Statement, the government is now going further, as set out in Chapter 3. These decisions will provide additional support to households struggling with the effects of higher inflation.

In the medium term, the government has announced that it will phase out the import of Russian oil by the end of 2022. This phased approach allows the UK enough time to adjust supply chains ensuring a smooth transition.

The government will soon be setting out an energy security plan. This will include measures across hydrocarbons, nuclear and renewables to support energy resilience and security while delivering affordable energy to consumers. Building on the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution, the government is raising its delivery ambitions across energy technologies to end the UK’s dependency on hydrocarbons from Russia.[footnote 14]

Box 1.A: The government’s response to the invasion of Ukraine

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s assault on Ukraine is an unprovoked, premeditated attack against a sovereign democratic state. The UK is at the forefront of efforts to provide essential support to Ukraine and the Ukrainian people, and to cut off funding to Putin’s regime.

Assisting Ukraine’s self-defence

UK military assistance to Ukraine is longstanding. Since 2015 the government has invested in building Ukrainian military capacity and training tens of thousands of Ukrainian troops. In the current conflict the UK has provided over £100 million of military aid to Ukraine, including thousands of anti-tank weapons. The government are enabling up to £3.5 billion of export finance to support Ukraine, including on defence capability.

The 2021 Integrated Review identified Russia as the most acute threat to the UK’s security. Reflecting this, the Ministry of Defence received the largest sustained spending increase since the Cold War, with a £24 billion cash uplift over four years. This settlement ensures the UK continues to exceed NATO’s 2% of GDP funding guideline and remain one of the leading defence spenders in NATO.

Humanitarian and economic support for the Ukrainian people

The UK is a leading bilateral humanitarian donor to Ukraine. The government has committed around £400 million in urgent economic and humanitarian support to Ukraine since the invasion, including fiscal support grants, donations and humanitarian aid. This includes a:

-

£220 million package of aid helping aid agencies provide medical supplies and basic necessities, saving lives and protecting vulnerable people

-

$100 million budgetary support grant contributing to the World Bank’s $700 million March emergency financing package for Ukraine. The UK supports the World Bank’s plans to deliver $3 billion to Ukraine this calendar year

-

£100 million package to boost the Ukrainian economy and reduce its reliance on gas imports including by co-financing a new World Bank energy efficiency programme.

The government stands ready to provide up to $500 million in guarantees for multilateral lending to Ukraine, enabling Multilateral Development Banks like the World Bank to significantly scale up their financial support if required. The government also strongly supported $1.4 billion in IMF emergency financing for Ukraine, which is being disbursed to help meet immediate financing needs.

The government has launched ‘Homes for Ukraine’, a new sponsorship humanitarian visa scheme to give Ukrainians forced to flee a route to safety, and the Ukraine Family Visa Scheme, allowing British nationals and Ukraine nationals settled here to bring Ukrainian family members to the UK. To support refugees being sponsored by the new Homes for Ukraine scheme, the government has committed to provide local authorities with £10,500 per person for support services, and between £3,000 and £8,755 per pupil for education services depending on phase of education, as well as £350 per month for sponsors for up to 12 months.

Maximising economic pressure on Putin’s regime

The UK has been at the forefront of the international community’s coordinated response to Putin’s aggression. Since Putin launched the Russian Federation’s invasion, the government has taken unprecedented measures to exclude Russian entities from international finance and the UK financial system. This includes asset freezes on Russian banks that collectively hold more than £250 billion in assets, as well as restricting financial transactions with the Central Bank of Russia. The government has imposed asset freezes on over 1000 high-value individuals, entities and subsidiaries. It has also barred the Russian state and over 3 million Russian companies from raising funds in the UK.

In addition, the government has announced additional import tariffs of 35% on around £900 million of Russian imports, imposed export bans on high-end luxury goods to Russia, barred Russian ships from the UK, and prohibited Russian aircraft from operating in UK airspace. The government has committed to phasing out imports of Russian oil and oil products by the end of the year, and will work with industry to achieve this smoothly through the newly established Taskforce on Oil.

These internationally coordinated sanctions are working. The value of the Russian Rouble plummeted to record lows and remains down by about a quarter of its pre-invasion value against the US dollar, the Moscow stock exchange has been largely suspended since 25 February, and the Central Bank of Russia has been forced to impose capital controls and more than doubled interest rates to 20%. External forecasts expect the Russian economy to go into recession in 2022.

The government also welcomes the widespread commitments from firms and investors to divest from Russian assets and urges businesses to think carefully about investments that would in any way support the Russian government.

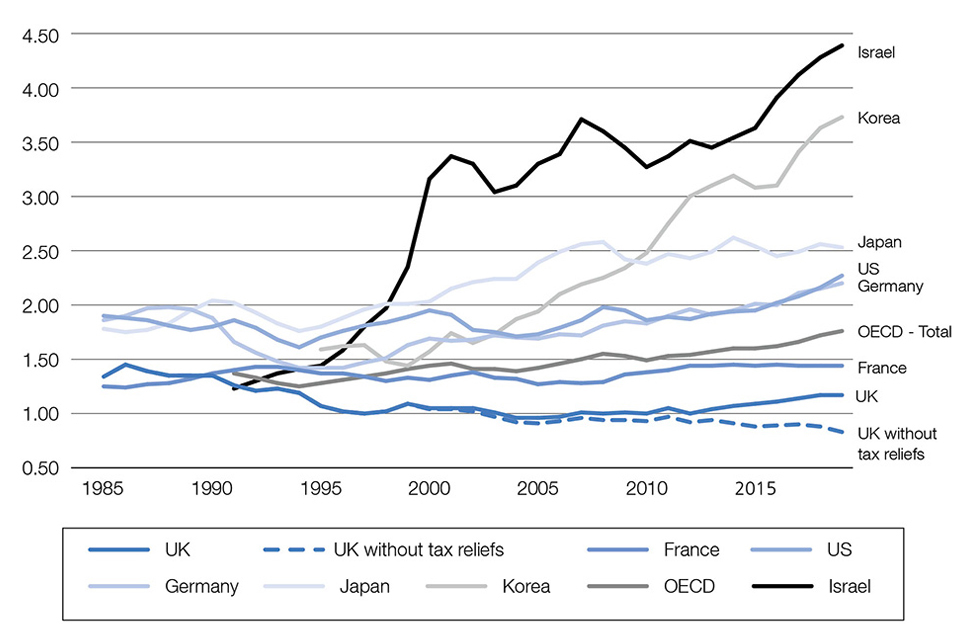

A new culture of enterprise

Improving productivity is the only way to deliver sustainable economic growth and increase living standards through higher real wages. The government has already taken important steps to meet its commitments to growth and to levelling-up through the super-deduction, the capital uplift and commitment to invest £20 billion per year in R&D (research and development) by 2024-25.

To go further, as the Chancellor set out in the Mais Lecture on 24 February, the government will focus on three priorities:[footnote 15]

-

Capital — cutting and reforming taxes on business investment to encourage firms to invest in productivity-enhancing assets

-

People — encouraging businesses to offer more high-quality employee training and exploring whether the current tax system – including the operation of the Apprenticeship Levy – is doing enough to incentivise businesses to invest in the right kinds of training

-

Ideas — delivering on the pledge to increase public investment in R&D and doing more through the tax system to encourage greater private sector investment in R&D

A responsible approach to sustainable public finances

Responsible management of the public finances is even more important at the current time given the increasing risks and uncertainty created by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Over the past year, the government has taken decisions to strengthen the public finances. This has allowed it to go further in supporting households in the Spring Statement, while still preserving fiscal space to tackle the challenges ahead. As highlighted in the response to the OBR’s Fiscal Risks Report published alongside Spring Statement, the government agrees with the OBR’s conclusion that “fiscal space may be the single most valuable risk management tool”.[footnote 16]

Public sector net borrowing (PSNB) in 2021-22 is expected to be £127.8 billion, lower than forecast in October 2021. As shown in table 1.2, this reflects stronger receipts outturn than expected in October,[footnote 17] combined with lower spending. Receipts remain higher than previously expected across the rest of the forecast, but beyond 2022-23 are partially offset by higher spending, driven higher by inflation and Bank Rate expectations. In 2022-23, higher debt interest payments due to inflation more than offset higher receipts and mean borrowing is higher than forecast in October 2021.

Table 1.2: Changes to the OBR’s forecast for public sector net borrowing since October 2021 (£ billion)(1)

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| October 2021 forecast | 319.9 | 183.0 | 83.0 | 61.6 | 46.3 | 46.4 | 44.0 |

| Total underlying forecast changes since October 2021 | -50.9 | 10.0 | -12.5 | -14.1 | -15.4 | -15.0 | |

| of which: | |||||||

| Receipts forecast | -37.4 | -30.1 | -33.8 | -36.9 | -37.7 | -35.9 | |

| Spending forecast | -13.5 | 40.1 | 21.2 | 22.8 | 22.2 | 20.9 | |

| of which: | |||||||

| Debt interest | 13.1 | 41.3 | 12.0 | 9.8 | 8.8 | 7.8 | |

| Welfare | -2.0 | -3.3 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.9 | |

| Total effect of government decisions since October 2021 | -4.2 | 6.1 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 2.5 | |

| of which: | |||||||

| Direct effects | -4.2 | 8.3 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 1.2 | |

| of which: | |||||||

| Student loan reforms | -2.3 | -11.2 | -3.8 | -4.8 | -6.1 | -7.0 | |

| Other policies | -1.9 | 19.4 | 4.4 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 8.3 | |

| Indirect effects | 0.0 | -2.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 | |

| Total change in borrowing | 2.0 | -55.2 | 16.1 | -11.4 | -9.8 | -11.5 | -12.4 |

| March 2022 forecast (2) | 321.9 | 127.8 | 99.1 | 50.2 | 36.5 | 34.8 | 31.6 |

| 1 Figures may not sum due to rounding. |

| 2 Figures for PSNB in 2020-21 are consistent with those published in the OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook. On 22 March, the ONS published the latest Public Sector Finances release, which includes revisions to 2020-21 outturn for PSNB. However, the OBR forecast was closed to new public finances data before these revisions were published. |

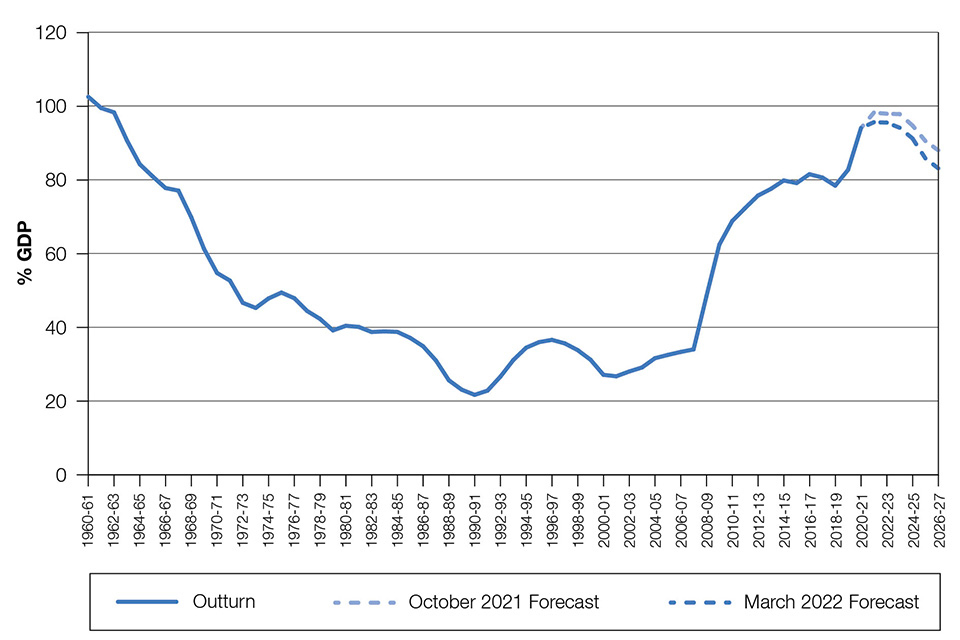

While debt is lower than forecast in October 2021, it remains historically high. Public sector net debt (PSND) increased from 82.7% of GDP in 2019-20 to 94.0% of GDP in 2020-21 and is expected to peak at 95.6% of GDP in 2021-22, the highest level since the 1960s.[footnote 18]

Chart 1.3: Public sector net debt

Chart 1.3: Public sector net debt

The data used for the October 2021 forecast are those originally published by the OBR in October 2021 not the amended data published in their March 2022 forecast where the GDP denominator in forecast years has been increased to align with upward revisions to nominal GDP for 2020-21 since the data for the October forecast was finalised.

Source: Office for National Statistics and Office for Budget Responsibility.

At this high level of debt, the public finances are more sensitive to changes in inflation and interest rates. In 2021, OBR analysis found that the first-year fiscal impact of a one percentage point rise in interest rates was six times greater than it was just before the financial crisis, and almost twice what it was before the pandemic.[footnote 19] As set out in the updated Charter for Budget Responsibility (the Charter) published alongside Autumn Budget 2021, the government is focused on monitoring and assessing the affordability of servicing public debt, in order to support the achievement of its fiscal objectives.

Spending on debt interest has risen sharply in recent months, with new monthly debt interest records in each of the last three months.[footnote 20]

Debt interest spending is forecast to reach £83.0 billion next year[footnote 21] – the highest nominal spending ever and the highest relative to GDP in over two decades.[footnote 22].This is nearly four times the amount spent on debt interest last year (£23.6 billion in 2020-21) and exceeds the budgets for day-to-day departmental spending on schools, the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice combined (totalling £78.3 billion in 2022-23).[footnote 23] Spending on debt interest in 2022-23 is £42.2 billion above the October forecast and the OBR say that the increase in the forecast for debt interest spending in 2022-23 “is also our largest forecast-to-forecast revision to debt interest on record”.[footnote 24]

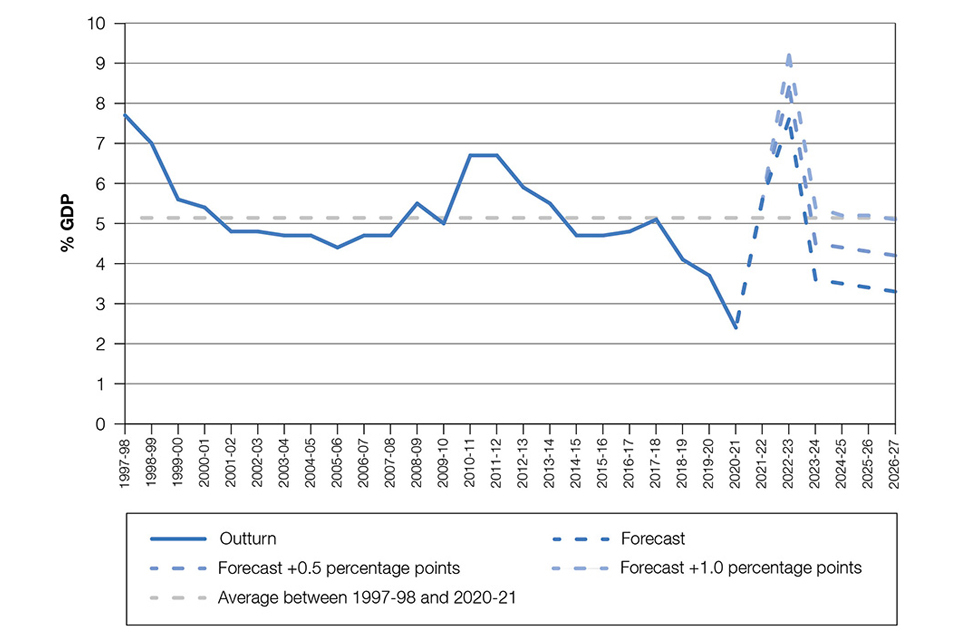

As a result, the debt interest to revenue ratio is expected to pass 6%, hitting 7.6% in 2022-23, as shown in chart 1.4. A further sustained one percentage point increase in interest rates and inflation would cost an additional £18.6 billion in 2024-25, and £21.1 billion by the end of the forecast.[footnote 25]

Chart 1.4: Debt interest to revenue ratio with illustrative interest rates & RPI shocks

Chart 1.4: Debt interest to revenue ratio with illustrative interest rates & RPI shocks

The debt interest to revenue ratio is defined as public sector net interest paid (gross interest paid less interest received) as a proportion of non-interest receipts. For illustrative rate and RPI shocks all increases are assumed to take effect at the beginning of 2022-23 and continue throughout the forecast.

Source: Office for National Statistics, Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations.

The Charter sets out the government’s fiscal mandate and supplementary fiscal targets announced at Autumn Budget 2021.[footnote 26] The government’s fiscal mandate to reduce underlying debt as a percentage of GDP in the medium term will reduce the risk created by exposure to changes in interest rates and inflation and keep the public finances on a sustainable footing in the years to come.

The fiscal mandate is supplemented by targets that require current spending to be sustainably funded through tax revenues, while also delivering on plans for significant investment in the economy. The OBR forecasts that the government is meeting all of its fiscal rules, with underlying debt falling and the current budget in surplus by the target year, 2024-25. Public sector net investment (PSNI) averages 2.5% of GDP over the forecast and the welfare cap is forecast to be met.

The decisions the government has taken, as outlined in Chapter 3, help address cost of living pressures while also maintaining prudent levels of fiscal space in the face of this uncertainty. The fiscal rules are met with a margin of safety of £27.8 billion (1.0% of GDP) against debt falling and the current budget is in surplus by £31.6 billion (1.2% of GDP). The current level of headroom is broadly in line with the headrooms held by previous Chancellors but the level varies from forecast to forecast, reflecting the economic and fiscal risks at the time.[footnote 27] At present there is elevated uncertainty surrounding the economic and fiscal outlook. As the OBR have said, this headroom “could be wiped out by relatively small changes to the economic outlook, including a 1.3 percentage point shortfall in GDP growth in 2024-25 or a 1.3 percentage point increase in the effective interest rate in 2024-25”.[footnote 28]

The government’s decisions help to strengthen the public sector balance sheet. This is in line with the objective set out in the Charter to strengthen over time a range of measures of the public sector balance sheet. A resilient balance sheet is an important part of sustainable fiscal policy and managing risk. As shown in table 1.3, the OBR forecasts that public sector net worth, which captures all public assets and liabilities, is improving in every year of the forecast, from -79.4% of GDP to -65.9% of GDP in 2026-27.

Table 1.3: Overview of the OBR’s fiscal forecast (% GDP)

| Forecast | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | |

| Public sector net debt (1) | 95.6 | 95.5 | 94.1 | 91.2 | 85.8 | 83.1 |

| Public sector net debt ex Bank of England (1) | 82.5 | 83.5 | 82.9 | 81.9 | 80.9 | 79.8 |

| Public sector net financial liabilities (1) | 83.3 | 82.6 | 80.6 | 78.1 | 75.9 | 73.9 |

| Public sector net worth (1) (2) (3) | 79.4 | 77.6 | 74.9 | 71.9 | 69.0 | 65.9 |

| General government gross debt (1) | 96.3 | 94.7 | 93.7 | 92.3 | 90.9 | 89.4 |

| Public sector net borrowing | 5.4 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Public sector net investment | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Current budget deficit | 3.8 | 1.7 | -0.8 | -1.2 | -1.3 | -1.4 |

| Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing | 6.1 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Cyclically-adjusted current budget deficit | 4.5 | 2.1 | -0.9 | -1.2 | -1.3 | -1.4 |

| General government net borrowing | 5.7 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| 1 Stock values at end of March; GDP centred on end of March. |

| 2 IMF Government Finance Statistics Manual (GFSM) basis. |

| 3 PSNW has been inverted to facilitate comparisons with the other stock metrics. |

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility |

Debt and reserves management

The Net Financing Requirement for the Debt Management Office in 2022-23 is forecast to be £147.9 billion; this will be financed by gilt sales of £124.7 billion and net Treasury bill sales for debt management purposes of £23.2 billion. National Savings and Investments will have a net financing target of £6 billion in 2022-23, within a range of £3 billion to £9 billion. The government’s financing plans for 2022-23 are set out in full in the ‘Debt management report 2022-23’, published alongside the Spring Statement.[footnote 29]

Public spending

Autumn Budget 2021 set UK government departments’ resource and capital Departmental Expenditure Limits (DEL) budgets and the devolved administrations’ block grants from 2022-23 to 2024-25. Total departmental spending will grow in real terms at 3.7% a year on average over this Parliament – a cash increase of £150 billion a year by 2024-25 (£88 billion in real terms). Total managed expenditure as a share of the economy is expected to increase across the Parliament to 41.3% in 2024-25. This is 2.2 percentage points higher than in 2019-20, and 1.4 percentage points higher when compared to 2007-08 when it stood at 39.9% [footnote 30].

The government’s focus is now on delivering the ambitious plans set out at Autumn Budget 2021. This will require a relentless focus on efficiency, so every pound of taxpayers’ money is directed towards providing the highest quality services at the best value and so the government can respond to new challenges from within overall spending plans.

The government is taking action to tackle waste and inefficiency across the public sector through a comprehensive efficiency agenda, including:

-

putting counter-fraud at the heart of decision-making through a new Public Sector Fraud Authority that will tackle fraud. The government is providing an additional £48.8 million of funding over three years to support the creation of a new Public Sector Fraud Authority and enhance counter-fraud work across the British Business Bank and the National Intelligence Service. The investment enables government and enforcement agencies to step up their efforts to reduce fraud and error, bring fraudsters to justice, and will recover millions of pounds

-

investing a further £12 million in HMRC to help prevent error and fraud in tax credits, and in turn support a smooth transition to Universal Credit

-

publishing guidance for a new series of Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs) reviews. These reviews will scrutinise the work and effectiveness of ALBs, aiming to deliver savings of at least 5% of their resource DEL budgets to be reinvested into frontline priorities

-

confirming that the NHS efficiency commitment will double from 1.1% to 2.2% a year to free up £4.75 billion to fund NHS priority areas which have the most impact on people’s lives

-

launching a new Innovation Challenge across central government departments to crowdsource ideas for how government can operate more efficiently.

These efficiencies and savings commitments must be underpinned by plans to deliver them and the government is taking steps to ensure this happens:

-

the Chancellor will chair a new Cabinet Committee on Efficiency and Value for Money to drive efficiency across the public sector and ensure departments demonstrate clear value for money for the taxpayer in government spending.

-

outcome Delivery Plans set out how departments will deliver on their priorities using agreed budgets over 2022-25, reflecting commitments to efficiencies and savings. They will be published after the start of the next financial year.

The government is maintaining the plans set out at Autumn Budget 2021. Day-to-day departmental spending (resource DEL) is set to grow by £100 billion a year in cash terms over the Parliament, and on capital DEL, public sector net investment will reach its highest sustained level as a proportion of GDP since the late 1970s.[footnote 31]

Table 1.4: Resource DEL (RDEL) excluding depreciation

| £ billion (current prices) | Outturn(1) | Plans(2) | Plans | Plans | Plans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | |

| Resource DEL excluding depreciation | |||||

| Health and Social Care | 136.3 | 146.1 | 167.9 | 173.4 | 177.4 |

| of which: NHS England | 125.9 | 134.6 | 151.8 | 157.4 | 162.6 |

| Education | 66.8 | 70.8 | 77.0 | 79.2 | 80.6 |

| of which: core schools | 47.6 | 49.8 | 53.8 | 55.3 | 56.8 |

| Home Office | 12.9 | 13.8 | 15.2 | 15.6 | 15.7 |

| Justice | 8.2 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 9.8 | 10.1 |

| Law Officers' Departments | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Defence | 30.6 | 31.6 | 32.4 | 32.2 | 32.4 |

| Single Intelligence Account | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office | 9.7 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 7.9 | 7.8 |

| ODA unallocated provision to hit 0.7% of GNI | - | - | - | - | 5.2 |

| DLUHC Local Government | 5.3 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 12.1 | 12.8 |

| DLUHC Levelling Up, Housing and Communities | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Transport | 3.6 | 4.1 | 7.8 | 6.8 | 5.7 |

| Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy | 2.1 | 3.3 | 8.4 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| Digital, Culture, Media and Sport | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.3 |

| International Trade | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Work and Pensions | 5.7 | 5.6 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| HM Revenue and Customs | 4.2 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.7 |

| HM Treasury | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Cabinet Office | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Scotland(3) | 30.3 | 33.2 | 35.1 | 35.7 | 36.3 |

| Wales(4) | 12.5 | 14.5 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 15.6 |

| Northern Ireland | 11.9 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 13.2 | 13.4 |

| Small and Independent Bodies | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| UK Shared Prosperity Fund | - | - | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| Reserves | - | - | 10.9 | 10.9 | 10.3 |

| Total Resource DEL | 354.6 | 384.0 | 441.9 | 442.7 | 453.9 |

| Ringfenced COVID-19 funding | 121.2 | 81.0 | - | - | - |

| Total Resource DEL including ringfenced COVID-19 funding | 475.8 | 465.1 | 441.9 | 442.7 | 453.9 |

| Allowance for Shortfall | - | -21.8 | -4.5 | -3.7 | -3.4 |

| Total Resource DEL excluding depreciation, post allowance for shortfall | 475.8 | 443.3 | 437.4 | 439.0 | 450.6 |

| 1 2020-21 figures reflect outturn in PESA, adjusted for provisional estimates of core spending. For devolved administrations, figures represent the Barnett consequentials of departmental COVID-19 funding less the element they carried forward from 2020-21 into 2021-22. |

| 2 2021-22 figures reflect the control totals set at Supplementary Estimates 2021. |

| 3 Resource DEL excluding depreciation is before adjustments for tax and welfare devolution. |

| 4 Resource DEL excluding depreciation is after adjustments for tax devolution. |

Table 1.5: Departmental Capital Budgets - Capital DEL (CDEL)

| £ billion (current prices) | Outturn(1) | Plans(2) | Plans | Plans | Plans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | |

| Capital DEL | |||||

| Health and Social Care | 8.6 | 9.2 | 10.6 | 10.5 | 11.3 |

| Education | 4.7 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 6.1 |

| Home Office | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Justice | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.4 |

| Law Officers' Departments | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Defence | 11.7 | 14.3 | 15.8 | 15.9 | 16.3 |

| Single Intelligence Account | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office | 2.8 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| DLUHC Levelling Up, Housing and Communities | 9.0 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 6.9 | 6.8 |

| Levelling Up Fund | - | - | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Transport | 16.9 | 19.0 | 20.0 | 19.9 | 20.5 |

| Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy | 18.8 | 21.9 | 19.2 | 20.8 | 21.2 |

| Digital, Culture, Media and Sport | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 0.9 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

| International Trade | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Work and Pensions | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| HM Revenue and Customs | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| HM Treasury | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cabinet Office | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Scotland | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.5 |

| Wales | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Northern Ireland | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Small and Independent Bodies | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| UK Shared Prosperity Fund | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Reserves | - | - | 4.9 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| Funding for leases reclassification exercise (IFRS16) | - | - | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Adjustment for Budget Exchange | - | - | -2.4 | - | - |

| Total Capital DEL excluding ringfenced COVID-19 funding | 88.0 | 96.1 | 107.8 | 111.5 | 111.9 |

| Ringfenced COVID-19 funding | 5.8 | 2.4 | - | - | - |

| Total Capital DEL including ringfenced COVID-19 funding | 93.8 | 98.5 | 107.8 | 111.5 | 111.9 |

| Remove Capital DEL not in PSGI(3) | -21.1 | -18.8 | -11.9 | -8.0 | -8.8 |

| Allowance for Shortfall | - | -10.5 | -9.9 | -8.8 | -8.2 |

| Public Sector Gross Investment in Capital DEL | 72.6 | 69.2 | 86.0 | 94.6 | 94.9 |

| 1 2020-21 figures reflect outturn in PESA, adjusted for provisional estimates of core spending. For devolved administrations, figures represent the Barnett consequentials of departmental COVID-19 funding less the element they carried forward from 2020-21 into 2021-22. |

| 2 2021-22 figures reflect the control totals set at Supplementary Estimates 2021. |

| 3 Capital DEL that does not form part of public sector gross investment in Capital DEL, including Financial Transactions in Capital DEL and Scottish Government capital. |

Table 1.6: Departmental Budgets for 2021-22

| £ billion (current prices) | Resource DEL excluding depreciation | Capital DEL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core | Ringfenced COVID-19 | Total | Core | Ringfenced COVID-19 | Total | |

| Health and Social Care | 146.1 | 39.2 | 185.3 | 9.2 | 1.2 | 10.4 |

| Education | 70.8 | 0.8 | 71.6 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 5.2 |

| Home Office | 13.8 | 1.2 | 15.1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Justice | 8.4 | 0.2 | 8.7 | 1.5 | - | 1.5 |

| Law Officers' Departments | 0.7 | - | 0.7 | 0.0 | - | 0.0 |

| Defence | 31.6 | - | 31.6 | 14.3 | - | 14.3 |

| Single Intelligence Account | 2.5 | - | 2.5 | 1.0 | - | 1.0 |

| Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office | 7.6 | 0.1 | 7.6 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.8 |

| DLUHC Local Government | 10.7 | 10.8 | 21.5 | 0.0 | - | 0.0 |

| DLUHC Levelling Up, Housing and Communities | 2.9 | 0.2 | 3.1 | 7.4 | - | 7.4 |

| Transport | 4.1 | 8.5 | 12.6 | 19.0 | 0.5 | 19.4 |

| Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy | 3.3 | 5.9 | 9.2 | 21.9 | 0.2 | 22.1 |

| Digital, Culture, Media and Sport | 1.7 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 4.2 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 1.4 | - | 1.4 |

| International Trade | 0.5 | - | 0.5 | 0.0 | - | 0.0 |

| Work and Pensions | 5.6 | 3.3 | 8.9 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| HM Revenue and Customs | 4.8 | 0.8 | 5.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| HM Treasury | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | - | 0.0 |

| Cabinet Office | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.4 | - | 0.4 |

| Scotland(1) | 33.2 | 4.6 | 37.8 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 5.6 |

| Wales(1) | 14.5 | 2.8 | 17.3 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| Northern Ireland(1) | 12.7 | 1.6 | 14.3 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.9 |

| Small and Independent Bodies | 2.7 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 0.4 | - | 0.4 |

| Total | 384.0 | 81.0 | 465.1 | 96.1 | 2.4 | 98.5 |

| Allowance for shortfall | - | - | -21.8 | - | - | -10.5 |

| Total post allowance for shortfall | - | - | 443.3 | - | - | 88.0 |

| 1 The Statement of Funding Policy provides further information on UK government funding for the devolved administrations. |

Total Managed Expenditure (TME) is the total amount of money that the government spends through departments, local authorities, other public bodies and social security. TME as a share of the economy is expected to increase across the Parliament from 39.1% in 2019-20 to 41.3% in 2024-25.[footnote 32]

Table 1.7 sets out planned TME, public sector current expenditure (PSCE) and public sector gross investment (PSGI) up to 2026-27.

Table 1.7: Total Managed Expenditure (TME)(1)

| £ billion (current prices) | Outturn 2019-20 |

Outturn 2020-21 |

Plans 2021-22 |

Plans 2022-23 |

Plans 2023-24 |

Plans 2024-25 |

Plans 2025-26 |

Plans 2026-27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Expenditure | ||||||||

| Resource AME | 406.2 | 480.9 | 430.6 | 488.6 | 482.4 | 498.0 | 512.4 | 530.0 |

| Resource DEL excluding depreciation(2)(3) | 345.5 | 475.8 | 465.1 | 441.9 | 442.7 | 453.9 | 471.5 | 489.0 |

| of which core RDEL excluding depreciation | 343.3 | 354.6 | 384.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| of which ringfenced COVID-19 funding | 2.2 | 121.2 | 81.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ringfenced depreciation | 38.0 | 33.1 | 38.2 | 42.5 | 43.7 | 45.2 | 46.9 | 48.7 |

| Total Public Sector Current Expenditure | 789.6 | 989.8 | 933.8 | 973.0 | 968.8 | 997.2 | 1030.9 | 1067.7 |

| Capital Expenditure | ||||||||

| Capital AME(4) | 24.1 | 31.4 | -5.0 | 5.8 | 20.0 | 17.9 | 17.7 | 17.0 |

| Capital DEL(2) | 70.2 | 93.8 | 98.5 | 107.8 | 111.5 | 111.9 | 117.1 | 121.4 |

| of which core CDEL | 70.2 | 88.0 | 96.1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| of which ringfenced COVID-19 funding | 0.0 | 5.8 | 2.4 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total Public Sector Gross Investment | 94.2 | 125.2 | 93.5 | 113.6 | 131.5 | 129.8 | 134.8 | 138.4 |

| Total Managed Expenditure | 883.9 | 1115.0 | 1027.3 | 1086.6 | 1100.3 | 1126.9 | 1165.7 | 1206.1 |

| Total Managed Expenditure % of GDP | 39.1% | 52.1% | 43.4% | 43.2% | 42.0% | 41.3% | 41.2% | 41.1% |

| 1 The 2019-20 and 2020-21 Resource DEL excluding depreciation and Capital DEL figures are final PESA outturns. Figures for 2021-22 onwards are plans. |

| 2 Resource DEL excluding ringfenced depreciation is the Treasury's primary control within resource budgets. Capital DEL is the Treasury's primary control within capital budgets. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) publishes Public Sector Current Expenditure in DEL and AME, and Public Sector Gross Investment in DEL and AME. A reconciliation is published by the OBR. |

| 3 Resource DEL excluding ringfenced depreciation includes funding for the council tax rebate measure in 2021-22 which will be recorded in the National Accounts in 2022-23 as an accounting adjustment. |

| 4 Capital AME includes the Office for Budget Responsibility's (OBR) forecast for the total expected cost of government loan guarantee schemes and the OBR’s standard capital allowance for shortfall. The OBR have revised down their estimate of the expected cost of guarantees on covid loans schemes. This downward revision scores as negative public sector gross investment in 2021-22. Combined with the capital allowance for shortfall, this has caused a negative capital AME forecast for 2021-22. |

| Source: HM Treasury Calculations and Office for Budget Responsibility EFO. |

Some policy measures do not directly affect PSNB in the same way as conventional spending or taxation. These include financial transactions, which predominantly affect the central government net cash requirement (CGNCR) and PSND. Table 1.8 shows the effect of the financial transactions announced since Autumn Budget 2021 on PSND.

Table 1.8: Financial Transactions from 2021-22 to 2026-27

| £ million | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | AME/DEL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student finance: eligibility for those relocating from Afghanistan under the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme | 0 | * | * | -5 | -5 | -5 | AME |

| Student finance: changes to fee caps, loan terms and eligible courses | 0 | 115 | 385 | 825 | 1,005 | 1,065 | AME |

| Total policy decisions | 0 | 115 | 385 | 820 | 1,000 | 1,060 |

Table 1.9: Departmental Capital Financial Transactions Budgets

| £ billion (current prices) | Outturn(1) | Plans | Plans | Plans | Plans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | |

| Financial Transactions budgets | |||||

| Health and Social Care | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Education | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Defence | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| DLUHC Levelling Up, Housing and Communities | 4.1 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Transport | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy(2) | 1.5 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Digital, Culture, Media and Sport | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Work and Pensions | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| HM Treasury | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Scotland | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Wales | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Northern Ireland | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Total Financial Transactions | 7.7 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| 1 2020-21 figures reflect outturn in PESA. For devolved administrations, figures represent the Barnett consequentials of departmental COVID-19 funding less the element they carried forward from 2020-21 into 2021-22. |

| 2 Funding in 2021-22 and 2022-23 include the support provided to Bulb as this is considered a financial transaction in the budgeting framework. |

As part of the forecast process, the government provides the OBR with an assumption for the future path of departmental spending. For the years beyond the Spending Review period, the government has maintained the assumptions set out at Autumn Budget 2021, growing resource and capital DEL in line with nominal GDP growth. Budgets beyond 2024-25 will be set at the next Spending Review.

The government committed to Parliament to return to spending 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) on Official Developmental Assistance (ODA) when on a sustainable basis the government is not borrowing for day-to-day spending and underlying debt is falling.

At the 2021 Spending Review, the government set ODA budgets accordingly, and reiterated its commitment to review and confirm each year, in accordance with the International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Act 2015, whether a return to spending 0.7% of GNI on ODA is possible against the latest fiscal forecast. In line with this approach, and noting the current macroeconomic and fiscal uncertainty, the government will determine whether the ODA fiscal tests will be met for 2023-24 at Budget 2022.

Helping families and businesses

The government is taking steps through Spring Statement to provide additional support to households and businesses. The government has prioritised using the improvement in the public finances to deliver reductions in tax, while maintaining a margin of safety against its fiscal rules.

Supporting households

Higher global energy and goods prices have already put pressure on household budgets and the government understands the challenges that many households are facing. The worsening outlook for inflation because of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will likely place additional pressure on households. The sanctions the UK and the international community have imposed do not come without costs, but it is the right course of action to stand against Putin’s aggression and show solidarity with the people of Ukraine.

Whilst the scale of the economic effects is highly uncertain, the largest effect on households from the conflict will come via higher energy costs. Most households will therefore be protected from immediate impacts through the OFGEM energy price cap until the autumn.

The government is continuing to monitor the economic effects of the conflict and the pressures on household finances. HM Treasury analysis published alongside this event shows the decisions made since the Spending Round 2019 have, on average, benefitted those in the lowest income deciles the most.[footnote 33]

While real wages are 3% above pre-pandemic levels, the government recognises the pressures on households across the income distribution.[footnote 34] Those on the lowest incomes will particularly feel the effects of higher inflation because they have less scope to adjust their expenditure in response to prices, and they tend to spend a greater proportion of their expenditure on electricity, gas, and other fuels.[footnote 35]

Improving energy efficiency is not only good for the climate but can also save households hundreds of pounds a year, helping to eliminate fuel poverty while reducing our reliance on imported gas. The government is already taking action to improve energy efficiency and encourage the electrification of heat.

Since March 2021, the government has committed to spend over £9.7 billion on decarbonising buildings. This includes £3 billion to upgrade the energy efficiency of up to half a million homes, saving hundreds of pounds in energy bills per year, and £2.5 billion to decarbonise nearly 2% of the total public estate per year.[footnote 36]

In addition, the government is expanding the Energy Company Obligation to £1 billion per year for 2022-26, requiring energy suppliers to improve the energy efficiency of low-income homes.[footnote 37] The government is also developing private rental sector minimum efficiency standards, which are expected to benefit over 2 million households in England and Wales, helping them save on their energy bills and significantly reducing fuel poverty in the private rented sector.

The government has already taken significant steps that will help households with the cost of living. These measures ensure work pays and help people keep more of what they earn to support households through the challenge ahead. They include:

-

reducing the Universal Credit taper rate from 63% to 55%, and increasing Universal Credit work allowances by £500 a year to make work pay

-

increasing the National Living Wage (NLW) for workers aged 23 and over by 6.6% to £9.50 an hour from April 2022

-

freezing alcohol and fuel duties to keep costs down

-

the £9 billion package announced in February 2022 to help households with rising energy bills this year

In addition to supporting households with the cost of living, the government is also working to address issues in supply chains where it can help, including from disruption to the transportation of goods, which has led to higher costs and delays for businesses and consumers. This includes measures to address a shortage of HGV drivers and ease the movement of goods into and across the UK, and ensuring the immigration system is responsive to business needs.

Spring Statement announces an increase in the annual National Insurance Primary Threshold and the Lower Profits Limit from £9,880 to £12,570 from July 2022, to align with the income tax personal allowance. This is a tax cut of over £6 billion and worth over £330 for a typical employee in the year from July. Around 70% of National Insurance contributions (NICs) payers will pay less NICs, even accounting for the introduction of the Health and Social Care Levy. This change will take 2.2 million people out of paying Class 1 and Class 4 NICs and the Health and Social Care Levy altogether. It brings into alignment the starting thresholds for income tax and NICs, making the taxation of income fairer, and these thresholds will remain aligned.

The government is also taking steps to ensure that self-employed individuals with lower earnings fully benefit. Spring Statement announces that from April 2022 self-employed individuals with profits between the Small Profits Threshold and Lower Profits Limit will continue to build up National Insurance credits but will not pay any Class 2 NICs. Taken together, these measures will meet the government’s ambition to ensure that the first £12,500 earned is tax free.

In addition, in response to fuel prices reaching their highest ever levels, Spring Statement announces a temporary 12-month cut to duty on petrol and diesel of 5p per litre. This measure represents a tax cut of around £2.4 billion over the next year. When compared with uprating fuel duty in 2022-23, cutting fuel duty to this level delivers savings for consumers worth over £5 billion over the next year and will save the average UK car driver around £100, van driver around £200 and haulier around £1,500, based on average fuel consumption.[footnote 38]

To help households improve energy efficiency and keep energy costs down – as well as supporting the UK’s long-term Net Zero ambitions – the government is extending the VAT relief available for the installation of energy saving materials (ESMs). Taking advantage of Brexit freedoms, the government will include additional technologies and remove the complex eligibility conditions, reversing a Court of Justice of the European Union ruling that unnecessarily restricted the application of the relief. The government will also increase the relief further by introducing a time-limited zero rate for the installation of ESMs. A typical family having roof top solar panels installed will save more than £1,000 in total on installation, and then £300 annually on their energy bills. The changes will take effect from April 2022. The Northern Ireland Executive will receive a Barnett share of the value of this relief until it can be introduced UK-wide.

To help the most vulnerable households with the cost of essentials such as food, clothing and utilities, the government is also providing an additional £500 million for the Household Support Fund from April, on top of the £500 million already provided since October 2021,[footnote 39] bringing total funding to £1 billion.

These new measures mean the government is now providing support worth over £22 billion in 2022-23 that will help households with the cost of living.

The government is continuing to monitor developments and the consequences for the cost of living, and will be ready to take further steps if needed to support households.

Supporting Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

The government recognises that, as well as households, businesses – particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – are also struggling with rising energy costs, recruiting staff, and navigating turbulent supply chains as the world economy recovers from the pandemic. SMEs support 16.3 million jobs – 61% of total private sector employment[footnote 40] – and a strong economy relies on the entrepreneurship of small businesses across the United Kingdom. That is why the government has and continues to prioritise support for SMEs. Spring Statement builds on measures previously announced and goes further.

The government has already reduced the burden of business rates in England. The business rates multiplier will be frozen in 2022-23, which is a tax cut for all ratepayers worth £4.6 billion over the next five years. Eligible retail, hospitality, and leisure businesses will also benefit from a new temporary 50% Business Rates Relief worth £1.7 billion. The package of changes is worth £7 billion over the next five years and means:

-

the average pub, with a rateable value of £21,000, will save £5,200

-

the average convenience store, with a rateable value of £28,500, will save £7,000

-

the average cinema, with a rateable value of £95,500, will save £24,000

To help SMEs gain the skills they need to succeed, the government is subsidising the cost of high-quality training. Help to Grow: Management offers businesses 12 weeks of world class leadership training through the UK’s top business schools, with government covering 90% of the cost. The cost of apprenticeship training is 95% subsidised for SMEs that do not pay the Apprenticeship Levy.

To support businesses to invest and grow, the temporary £1 million level of the Annual Investment Allowance has been extended to 31 March 2023. This is the highest level of support for capital expenditure ever provided through the Annual Investment Allowance and provides generous relief for investment across over a million SMEs. The government is also helping firms to adopt new digital technologies, with Help to Grow: Digital, offering eligible SMEs a 50% discount on approved software worth up to £5,000.

To support the decarbonisation of non-domestic buildings, the government is introducing targeted business rates exemptions for eligible plant and machinery used in onsite renewable energy generation and storage, and a 100% relief for eligible low-carbon heat networks with their own rates bill. Spring Statement announces that these measures will now take effect from April 2022, a year earlier than previously planned.

Finally, the government is supporting small businesses to do what they do best: create jobs. In April 2020, the government increased the Employment Allowance from £3,000 to £4,000. Spring Statement announces a further increase from April 2022, meaning eligible employers will be able to reduce their employer NICs bills by up to £5,000 per year – this is a tax cut worth up to £1,000 per employer. As a result, businesses will be able to employ four full-time employees on the NLW without paying employer NICs. This measure will benefit around 495,000 businesses, including around 50,000 businesses which will be taken out of paying NICs and the Health and Social Care Levy entirely. In total, this means that from April 2022, 670,000 businesses will not pay NICs and the Health and Social Care Levy due to the Employment Allowance.

Policy decisions

The following chapter sets out all Spring Statement 2022 policy decisions. Unless stated otherwise, the decisions set out are ones which are announced at the Statement.

Table 3.1 shows the cost or yield of all Spring Statement 2022 decisions with a direct effect on PSNB in the years up to 2026-27. This includes tax measures, changes to DEL and measures affecting annually managed expenditure (AME).

The government is also publishing the methodology underpinning the calculation of the fiscal impact of each policy decision. This is included in ‘Spring Statement 2022: policy costings’ published alongside Spring Statement.

Table 3.1: Spring Statement 2022 policy decisions (£ million)(1)

| Head(2) | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helping with the cost of living and supporting businesses | ||||||||

| 1 National Insurance: increase annual Primary Threshold and Lower Profits Limit to £12,570 from July 2022 | Tax | 0 | -6,250 | -5,960 | -4,855 | -4,330 | -4,495 | |

| 2 National Insurance: reduce Class 2 NICs payments to nil between the Small Profits Threshold and Lower Profits Limit | Tax | 0 | -65 | -100 | -100 | -95 | -95 | |

| 3 Income Tax: reduce basic rate from 20% to 19% from April 2024(3) | Tax | 0 | 0 | 0 | -5,335 | -6,055 | -5,975 | |

| 4 Fuel Duty: reduce main rates of petrol and diesel by 5p per litre, and other rates proportionately, for 12 months | Tax | -45 | -2,385 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 Energy bills support package | Spend | 0 | -9,050 | +1,195 | +1,195 | +1,195 | +1,195 | |

| 6 Household Support Fund | Spend | 0 | -500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 VAT: expanding the VAT relief for energy saving materials from April 2022 | Tax | 0 | -45 | -50 | -60 | -60 | -65 | |

| 8 Employment Allowance: increase from £4,000 to £5,000 | Tax | 0 | -425 | -420 | -425 | -435 | -440 | |

| 9 Business Rates: bring forward implementation of green reliefs by one year | Tax | 0 | -40 | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tackling fraud and supporting compliance | ||||||||

| 10 HMRC: investment in compliance | Tax | +85 | +455 | +855 | +815 | +415 | +530 | |

| 11 DWP: investment in compliance | Spend | +5 | +55 | +290 | +570 | +580 | +780 | |

| Previously announced policy decisions and mechanical changes to spending assumption | ||||||||

| Mechanical changes to spending assumption | ||||||||

| 12 Spending assumption: mechanical update in line with forecast | Spend | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -15 | +545 | |

| Higher Education reform package | ||||||||

| 13 Student finance: changes to fee caps, loan terms and eligible courses - upfront accrual of impacts (not cash) over the lifetime of loans4 | Spend | +2,285 | +11,150 | +3,805 | +4,845 | +6,095 | +7,035 | |

| 14 Memo: impact on public sector net debt - net impact of changes on cash outlays and cash repayments over the forecast period | 0 | +115 | +385 | +825 | +1,005 | +1,065 | ||

| Other tax decisions | ||||||||

| 15 VAT: delay implementation of penalty reform by 9 months to January 2023 | Tax | 0 | -5 | -70 | -45 | -5 | -5 | |

| 16 Income Tax Self Assessment: January 2022 one month late filing and payment penalty waiver | Tax | -5 | -10 | -5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 17 Tariff changes since Autumn Budget 2021 | Tax | -15 | -60 | -55 | -55 | -55 | -55 | |

| 18 Income Tax and National Insurance: one year extension to the exemption for employer-reimbursed coronavirus antigen tests | Tax | 0 | -10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 19 Updating regulations for derivatives used to hedge foreign exchange risks in share transactions from April 2022 | Tax | 0 | +10 | +5 | 0 | -5 | -5 | |

| Other spending decisions | ||||||||

| 20 Special Administration Regime: Bulb Energy | Spend | 0 | -1,005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 21 Statutory Sick Pay: extension to rebate scheme | Spend | -35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 22 Goodwin Case (case on discrimination in Teachers’ Pension Scheme) | Spend | -60 | -140 | -75 | -50 | -50 | -50 | |

| 23 Student finance: eligibility for those relocating from Afghanistan under the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme | Spend | 0 | * | * | * | -5 | -5 | |

| 24 West Yorkshire, South Yorkshire and North of Tyne borrowing powers | Spend | -10 | -40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 25 Operational measures to manage constraints within the Personal Independence Payment assessment system | Spend | -30 | -55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total policy decisions(5) | +2,175 | -8,415 | -585 | -3,500 | -2,825 | -1,105 | ||

| Memo: Total policy decisions excluding Higher Education reform package | -110 | -19,565 | -4,390 | -8,345 | -8,920 | -8,140 | ||

| o/w Total spending policy decisions | -130 | -10,735 | +1,410 | +1,715 | +1,705 | +2,465 | ||

| o/w Total tax policy decisions | +20 | -8,830 | -5,800 | -10,060 | -10,625 | -10,605 | ||

| *Negligible |

| 1 Costings reflect the OBR’s latest economic and fiscal determinants. |

| 2 Many measures have both tax and spend impacts. Measures are identified as tax or spend on the basis of their largest impact. |

| 3 Non-dividend income. |

| 4 Under the methodology announced by the Office for National Statistics in December 2018, the extension of loans to students is seen as a combination of lending and government expenditure, where the latter represents the estimated proportion that is not expected to be repaid in future. These PSNB savings reflect that we now expect a greater proportion to be repaid over the full length of the loans, which reduces the amount recorded as government expenditure up front. The PSNB savings do not translate into an equivalent reduction in Public Sector Net Debt in the scorecard period, because the effects on debt will be spread over the life of the loans, as cash paid out or repaid in each year. |

| 5 Totals may not sum due to rounding. |

With the economy continuing to recover following COVID-19 and the public finances on a stronger footing, Spring Statement announces reductions in tax to help with current cost-of-living pressures. It also sets out actions to meet the government’s commitment to allow hard-working families and individuals to keep more of their earned income, and to create an environment that promotes private sector-led growth.

HM Treasury analysis published alongside this document shows that, after the measures announced today:[footnote 41]

-

government decisions since Spending Round 2019 have benefitted the lowest-income households the most, as a proportion of income

-

the impact of government policy since Spending Round 2019 on households in the bottom four deciles is expected to be worth more than £1,000 a year, while there will have been a net benefit on average for the poorest 80% of households

-

government policy continues to be highly redistributive: in 2024-25, the poorest 60% of households will receive more in public spending than they contribute in tax, and households in the lowest income decile will receive, on average, over £4 in public spending for every £1 they pay in tax[footnote 42]

-

on average, the combined impact of personal tax and welfare decisions made since Spending Round 2019 is progressive, placing the largest burden on higher-income households as a proportion of income

Details of policy decisions

Increasing National Insurance thresholds – The annual National Insurance Primary Threshold and Lower Profits Limit, for employees and the self-employed respectively, will increase from £9,880 to £12,570 from July 2022. This increase will benefit almost 30 million people, with a typical employee saving over £330 in the year from July. Around 70% of NICs payers will pay less NICs, even after accounting for the introduction of the Health and Social Care Levy. Around 2.2 million people will be taken out of paying Class 1 and Class 4 NICs and the Health and Social Care Levy entirely, on top of the 6.1 million who already do not pay NICs. July is the earliest date that will allow all payroll software developers and employers to update their systems and implement changes.

Reducing Class 2 NICs payments for low earners – From April, self-employed individuals with profits between the Small Profits Threshold and Lower Profits Limit will not pay class 2 NICs, meaning lower-earning self-employed people can keep more of what they earn while continuing to build up National Insurance credits. Over the year as a whole, the Lower Profits Limit, the threshold below which self-employed people do not pay National Insurance, is equivalent to an annualised threshold of £9,880 between April to June, and £12,570 from July. This change represents a tax cut for around 500,000 self-employed people worth up to £165 per year.

Increasing the Employment Allowance – The Employment Allowance will increase from April 2022, meaning eligible employers will be able to reduce their employer NICs bills by up to £5,000 per year – a tax cut worth up to £1,000 per employer. As a result, businesses will be able to employ four full-time employees on the NLW without paying any employer NICs. This measure will benefit around 495,000 businesses, including around 50,000 businesses which will be taken out of paying NICs and the Health and Social Care Levy entirely. In total, this means that from April 2022, up to 670,000 businesses will not pay NICs and the Health and Social Care Levy due to the Employment Allowance.

Basic rate of income tax – The government will reduce the basic rate of income tax to 19% from April 2024. This is a tax cut of over £5 billion a year, and represents the first cut in the basic rate of income tax in 16 years. This will apply to the basic rate of non-savings, non-dividend income for taxpayers in England, Wales and Northern Ireland; the savings basic rate which applies to savings income for taxpayers across the UK; and the default basic rate which applies to a very limited category of income taxpayers made up primarily of trustees and non-residents. The change will be implemented in a future Finance Bill. A three-year transition period for Gift Aid relief will apply, to maintain the income tax basic rate relief at 20% until April 2027. The reduction in the basic rate for non-savings-non-dividend income will not apply for Scottish taxpayers because the power to set these rates is devolved to the Scottish Government. Under the agreed Fiscal Framework the Scottish Government will receive additional funding, worth around £350 million in 2024-25. It is for the Scottish Government to use this additional funding as they choose to, including on reducing income tax or other taxes, or increased spending.

Temporary cut to fuel duty – The government will cut the duty on petrol and diesel by 5p per litre for 12 months. This will take effect from 6pm on 23 March on a UK-wide basis. This is the largest cash-terms cut across all fuel duty rates at once ever, and is only the second time in 20 years that main rates of petrol and diesel have been cut.[footnote 43] This cut represents savings for households and businesses worth around £2.4 billion in 2022-23. Where practical, a proportionate cut will also apply to fuel duty rates which are lower than the main rates for petrol and diesel, including red diesel.