State of the water environment: long-term trends in river quality in England: 2024

Updated 22 May 2025

Applies to England

This report presents the results of an analysis of trends in water quality at a set of long-term river monitoring sites in England. The characteristics considered are the concentrations of nutrients (orthophosphate, nitrate, nitrite), ammonia, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and selected metals/metalloids (afterwards referred to as metals) - arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, nickel and zinc. These are important basic measures of river water quality. The Environment Agency carried out this data analysis in 2024.

1. Description of monitoring network

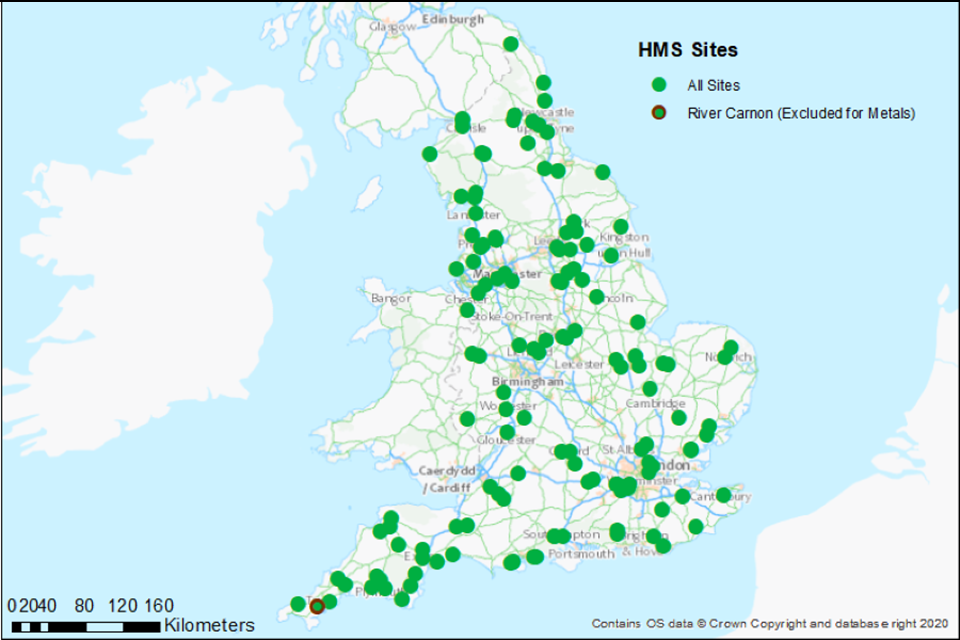

The Harmonised Monitoring Scheme (HMS) network provides a reliable and consistent data set for assessing how the water quality of England’s principal rivers has changed over time. Data gathered at HMS sampling points up to the end of 2023 were used for this analysis. Although the HMS was originally conceived to cover Great Britain, GB-wide reporting of trends as official statistics ceased in 2013. This report uses data from the 135 HMS sites in England. The sampling points are in the principal rivers of England (Figure 1), and many are sited at the lower end of these rivers, just above the tidal limit. There are also some HMS sampling points at the confluences of major tributaries of the larger rivers. The layout of these sampling points means that they are not intended to be representative of English rivers of all sizes: in particular, smaller rivers and streams are not well covered by this network. Many of the HMS sampling points are located close to flow gauging stations. Simpson (1980) provides details of the reasons for developing and standardising the monitoring network.

The data consist of spot samples of the water quality, providing continuity over multiple decades. There are occasional data gaps where fewer than 135 sites were sampled, including periods where no sites were sampled. Reasons for this include the foot and mouth disease outbreak in 2001, and COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020 and 2021. However, most sites were sampled at least once a month over the periods considered.

The data reflect the combined effects of natural processes and pollution in the catchments upstream of the sampling points. This includes the effect of control measures for point and diffuse sources of pollution, and other influences including natural variation in space and time.

Figure 1. Location of Harmonised Monitoring Scheme sampling points in England

This map shows the location of the 135 HMS sites in England included in the analysis. One site on the River Carnon is highlighted as it was excluded in the calculation of concentrations for metals – the reason for this is covered later in this report.

Data for the following water quality properties (determinands) have been used:

- ammonia as nitrogen (N)

- biochemical oxygen demand – BOD

- orthophosphate – as phosphorus (P)

- nitrate – as nitrogen (N)

- nitrite – as nitrogen (N)

- arsenic

- cadmium

- chromium

- copper

- lead

- nickel

- zinc

In each case, artificially elevated concentrations can degrade ecological condition, and limit the usability of water resources for drinking, recreation and other purposes.

Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) is a measure of the amount of oxygen required by microorganisms to break down organic matter in water. High BOD levels in rivers can indicate pollution from organic waste, including inadequately treated sewage which can deplete dissolved oxygen and harm aquatic life.

Elevated levels of nutrients, particularly phosphorus (as phosphate) and nitrogen (as nitrite and nitrate) most often originate from sewage effluent and agricultural runoff. These nutrients can lead to excessive growth of nuisance algae and aquatic plants, a phenomenon known as ‘eutrophication.’ Eutrophication disrupts aquatic ecosystems by causing fluctuations in dissolved oxygen levels. You can find further information in:

Ammonia can originate from sewage effluent, agricultural runoff and industrial discharges. It is a significant pollutant in freshwater due to its toxicity to aquatic life, particularly fish and invertebrates. Even at low concentrations it can impair respiration and damage tissue. Freshwater bacteria convert ammonia into nitrite and then nitrate, therefore ammonia can also contribute to eutrophication.

Dissolved metals can be toxic at elevated concentrations and can accumulate in sediments and organisms, posing risks to ecosystems and human health. Metal pollution arises from mining activity, sewage effluent, discharges from industry and manufacturing, urban runoff, energy production, road transport, the waste sector (including leaching from landfill) and the agricultural sector. Dissolved metals can also come from natural sources such as rock weathering. These metals can enter water via airborne routes either directly or indirectly via land. Sources of metal-laden airborne particulates include power generation, waste incineration and crematoria.

The most severe metal pollution in rivers is caused by discharges from abandoned metal mines, which are also the largest source of metals to freshwaters and seas. Around 3% of English rivers are polluted by harmful metals such as zinc, cadmium, lead, nickel, copper and arsenic from abandoned metal mines. Although almost all the mines closed in the early 1900s, contaminated mine water released through old drainage tunnels continues to pollute rivers. Mine waters discharge about half the metal load such as cadmium, zinc and lead released to rivers. This is as much as all permitted industrial activities (Mayes and others, 2010). In addition, river sediments and floodplain soils are contaminated with metals for many 10s of kilometres downstream of the mines. These represent a substantial reservoir of metals that continue to be released into rivers alongside inputs from mine water. You can find further information in Mine waters: challenges for the water environment

2. Analysis carried out

2.1 Data filtering

Data were analysed for nutrients, ammonia and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) from 1980 and metals from 1990. Before those dates, data availability across the network is more variable. As the focus of this analysis is on longer term trends, any data collected in response to pollution incidents were excluded. These excluded data represent a very small proportion of the total data available. Data used includes samples taken for long-term surveillance monitoring and for local investigations. Data were filtered to retain only samples collected between 7am and 5pm, although samples taken outside of those times were very rare. Sampling frequency varies over the data set. There are more weekly samples in the earlier years and generally monthly samples in the later years. For any site and determinand, if more than one sample was taken in a month, one sample was retained at random for this analysis, the others being discarded. This was to avoid any potential bias caused by changes in sampling frequency across the time period being considered.

Data for 135 sites were analysed for nutrients, ammonia and BOD, and 134 sites for metals. The total number of samples used in the calculations from 1980 to 2023 varied between 48,000 and 60,000 for nutrients, and between 35,000 and 41,000 for metals.

Nationally-coordinated monitoring of BOD ceased in 2014. Data for BOD concentrations after 2014 are available for some HMS sites where BOD was monitored for local reasons. Annual means from 2015 onwards are reported here where data are available, with the caveat that the underlying data used for calculating BOD in recent years are more uncertain and may be less representative of the full data set.

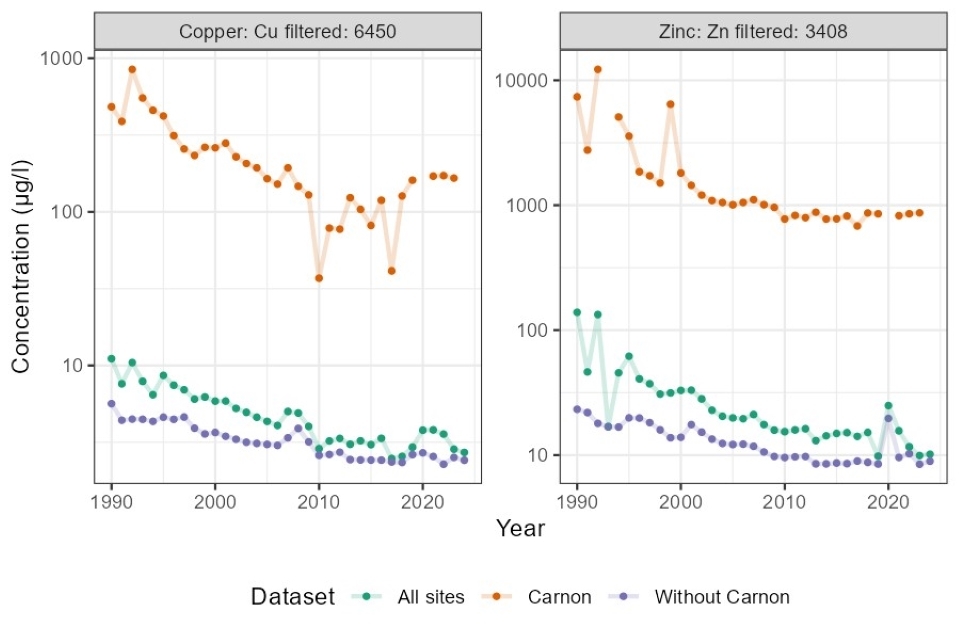

For metals, one site the River Carnon at Devoran Bridge in Cornwall was excluded from the calculations. This is because of severe metal pollution over the entire period of the data at this site, including a major pollution incident in 1992. Including data from this site would result in heavy bias towards the trends at this site and not represent trends observed across all sites. Additional information is presented in the technical appendix for the River Carnon alone, and the HMS data set including and excluding the Carnon.

All data consist of water samples analysed at the laboratories of the Environment Agency and its predecessors the National Rivers Authority and the regional water authorities. For most determinands, at least some measurements are below the analytical limit of detection (LOD). The percentage of values reported as below the LOD varied between 0.8% (nitrate) and 25% (ammonia) for the non-metals, and between 10% (copper) and 73% (cadmium) for metals. Analytical LODs for individual determinands change both spatially, especially for earlier data, and over time.

The annual arithmetic mean values are calculated using an approach called Regression on Order Statistics (Lee and Helsel, 2005; Millard, 2013). This produces unbiased estimates of the arithmetic means and their confidence intervals when some values in the dataset are recorded as being below the analytical limit of detection. This is a change from previous HMS reporting where values recorded as less than the LOD were substituted with half the limit of detection value before the mean was calculated. The method used here is more robust (for example it is not affected by changes in LODs over time) and produces more realistic confidence intervals.

95% confidence intervals for each annual mean are derived as part of the analysis. These confidence intervals are approximate. The 2 main reasons for this are firstly, all data are pooled for each year without considering the correlation between data points monitored at the same sites and secondly, seasonality and the influence of missing sites/samples/portions of the year were not considered.

The results of our analysis are presented below as time series graphs showing the annual arithmetic mean concentrations of nutrients, ammonia and BOD (in milligrams per litre, mg/l) and metals (in micrograms per litre, µg/l) with a 95% confidence interval for the mean. Years with fewer than 200 observations for a determinand are not plotted on the graphs, as the analysis will be more uncertain due to the low sample size. This mostly affects the time series of BOD: after 2014, only 4 years have more than 200 samples (2015, 2016, 2019 and 2023).

For all determinands, the Environment Agency’s 4 digit identifier code is shown on each graph below. These are the same as the codes available in the publicly available Environment Agency water quality archive accessible via the Defra Data Services Platform.

Ammonia, orthophosphate, nitrate and nitrite are quantified as the concentration of elemental phosphorus/nitrogen. The concentrations of metals are the filtered values; no bioavailability calculations were performed on the data.

For certain metals in individual years, upper 95% confidence intervals have been truncated in the graphs. These adjustments are also summarised in the table below, in the technical appendix. This truncation was made in situations (determinand-year combinations) where including their full range on the graphs would have obscured any detail of the changes at lower concentrations (typically the samples taken in later years). These truncated intervals are illustrated by dotted rather than solid lines in the graphs. Furthermore, for a limited number of cases for ammonia and BOD, individual values for 1989 have been removed entirely from the graphs, as the calculated values were deemed to be unrealistic outliers.

Data collected before the year 2000 are not routinely shared on the open data platform, although they are available on request. The exact data used in this analysis and the scripts used to process and graph the data are available on request from the Environment Agency.

3. Results

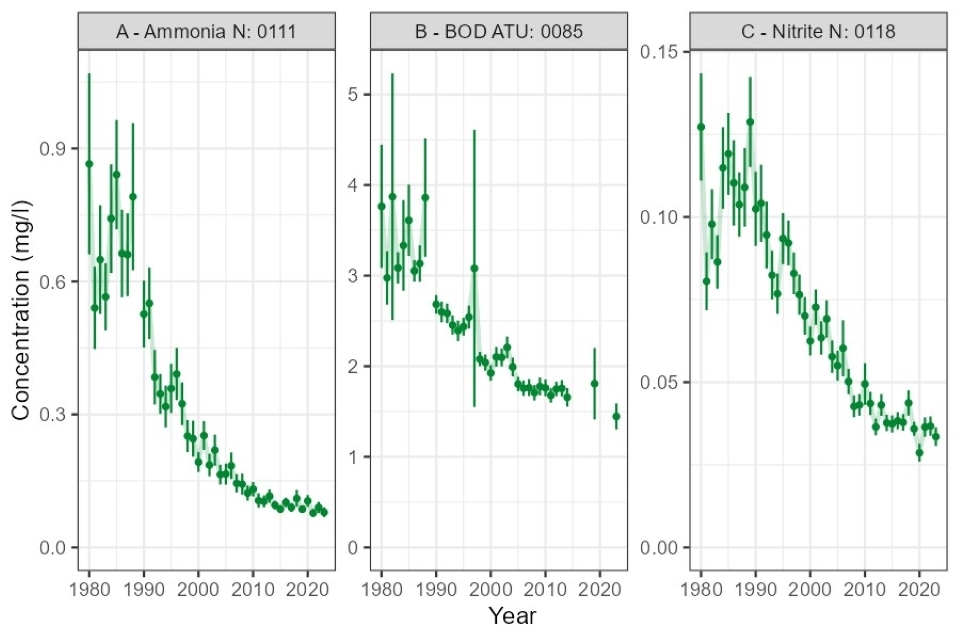

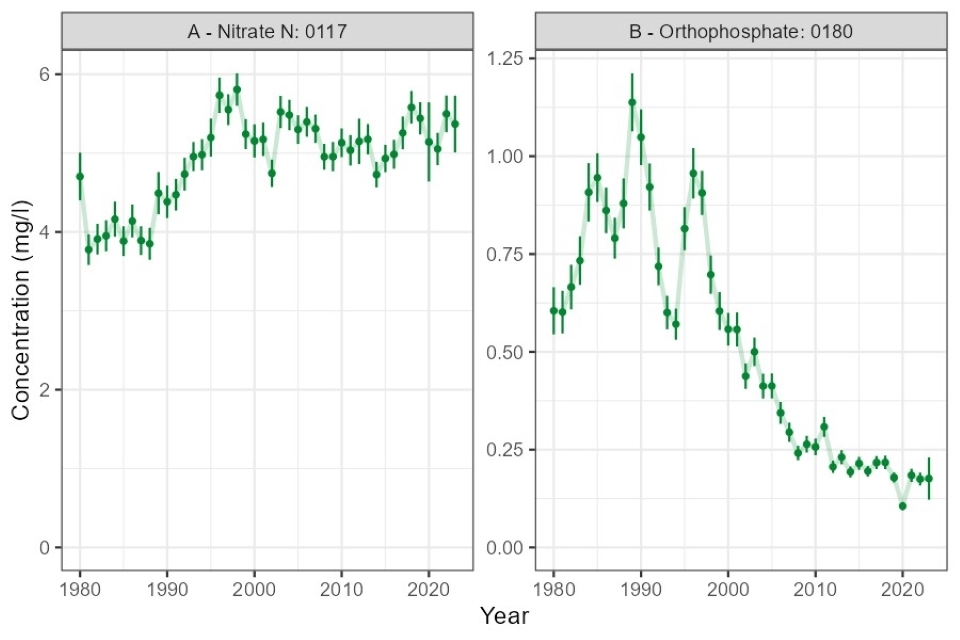

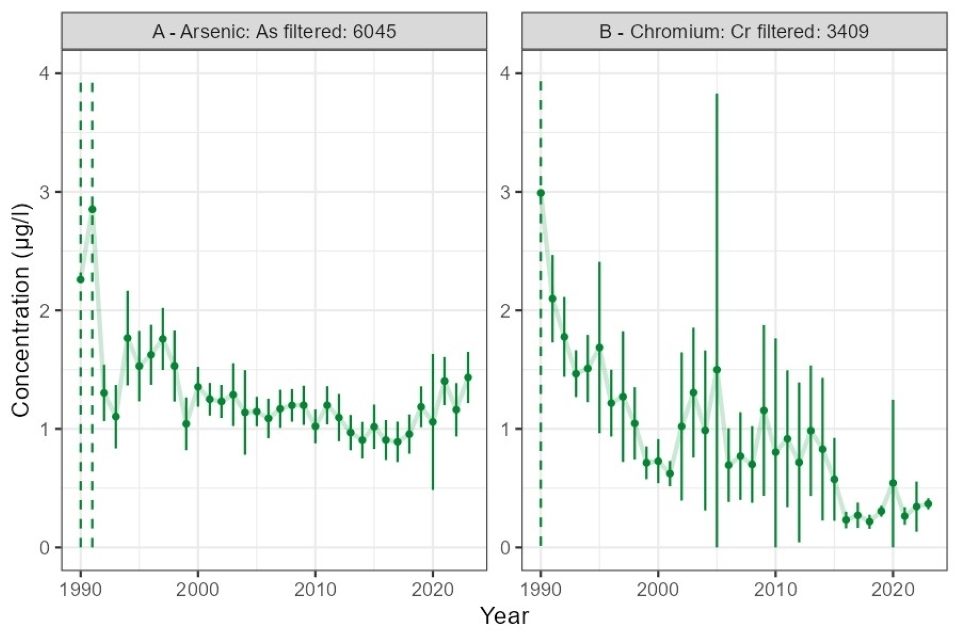

The long-term time series graphs for nutrients, ammonia, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and metals are presented in figures 2-6. For each calendar year, the annual arithmetic mean, along with a 95% confidence interval is shown. Some confidence intervals are truncated as described above, and in Appendix A, these are shown as dashed lines. For each graph, the title includes the determinand name and internal determinand code.

Figure 2. England Harmonised Monitoring Scheme (HMS) sites: trends from 1980 to 2023 in arithmetic mean concentration (with 95% confidence interval) of A: ammonia as N, B: BOD (note: ATU indicates that in the laboratory allylthiourea is added to suppress nitrification during the test) and C: nitrite as N.

Figure 3. England HMS sites: trends from 1980 to 2023 in arithmetic mean concentration (with 95% confidence interval) of A: nitrate as N, B: orthophosphate.

Figure 4. England HMS sites: trends in arithmetic mean concentration (dissolved, filtered, with 95% confidence interval) from 1990 to 2023 of A: arsenic, B: chromium. Dashed lines indicate truncated upper confidence interval (see Appendix A).

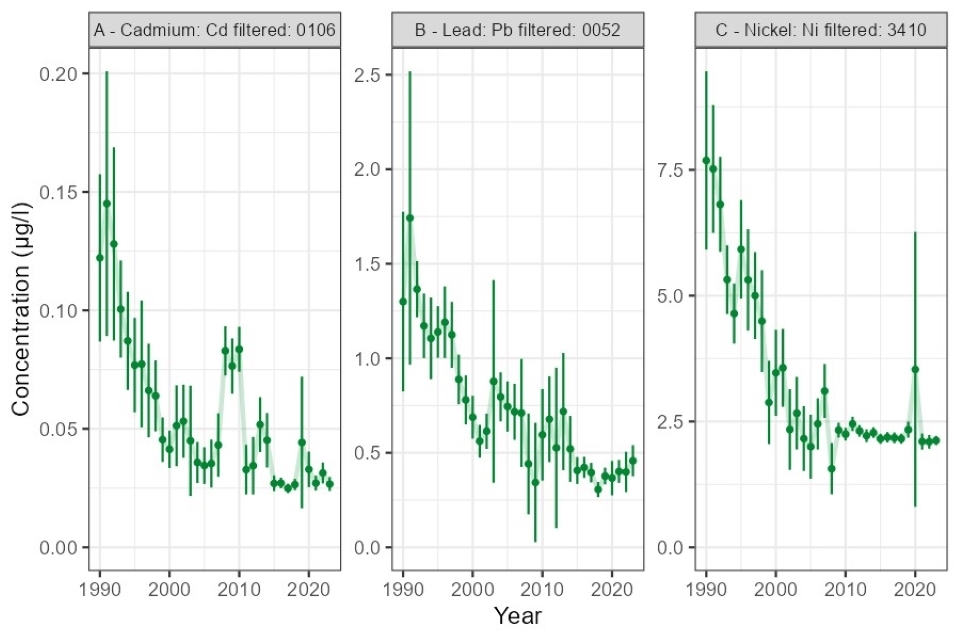

Figure 5. England HMS sites: trends in arithmetic mean concentration (dissolved, filtered, with 95% confidence interval) from 1990 to 2023 of A: cadmium, B: lead, C: nickel. See text for further information.

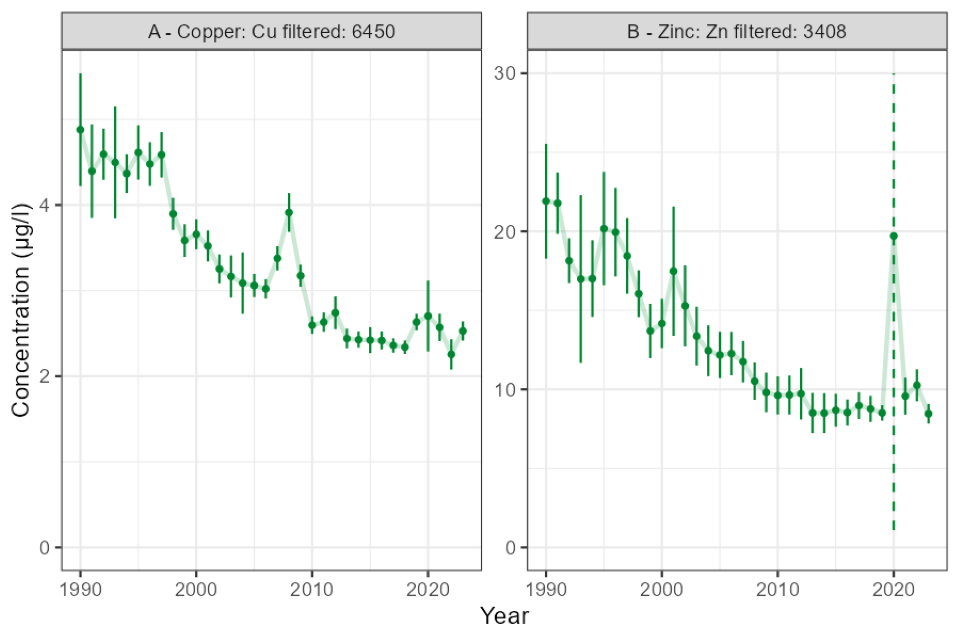

Figure 6. England HMS sites: trends in arithmetic mean concentration (dissolved, filtered, with 95% confidence interval) from 1990 to 2023 of A: copper, B: zinc. Dashed lines indicate truncated upper confidence interval (see Appendix A).

4. What the graphs show

The graphs for the dissolved metals above extend back to 1990, while the graphs for the other determinands extend back to 1980. However, for consistency, the percentage reduction figures given below are for the period 1990-2023.

For orthophosphate, nitrite, ammonia and BOD, concentrations have substantially reduced over the period 1990 to 2023: arithmetic mean ammonia concentrations have reduced by 85%, BOD by 46% and orthophosphate by 83%. Concentrations have continued to decrease in the period from 2000 and from 2010, although in recent years there are relatively little available data for BOD.

Arithmetic mean nitrate concentration increased by 23% over the period 1990 to 2023. However, from the year of peak nitrate concentration (1998), it has decreased by 19%.

Alongside these reductions for in-river concentrations, the Environment Agency has previously documented the reductions in pollution loads to rivers from water company sewage treatment works: ammonia by 80%, BOD by 55% and phosphate by 68% (percentage change figures from 1995 to 2020 taken from Regulating for people, the environment and growth, 2021.

In addition, nitrogen and phosphate additions from agriculture have declined significantly (Agriculture in the United Kingdom 2023) resulting in a reduction in soil nutrient balances (Environmental Improvement Plan: annual progress report 2023 to 2024). A similar analysis of national agriculture programme water quality data (consisting of sites with limited sewage influence) may be included in future versions of this report.

Concentrations of all dissolved metals have substantially decreased between 1990 and 2023. Between these dates, arithmetic mean cadmium, chromium and nickel concentration have all decreased by more than 70%; lead and zinc concentrations have decreased by more than 50%. Arithmetic mean arsenic concentrations have decreased by around 37% and copper by 48%. It is important to note that the reductions in concentrations for metals mostly occurred in the period between 1990 and the early 2000s. Since 2010, the annual means suggest concentrations are neither decreasing nor increasing, although there is still inter-year variation.

Trends for individual rivers will vary around these averages. Because of the logarithmic nature of concentration data, which may vary over 3 orders of magnitude, trends in arithmetic means may be dominated by the trends of the sites with the highest concentrations. The geometric mean will be less influenced by the sites and samples with the highest concentrations. Trends have also been derived for geometric mean concentrations using a statistical modelling approach. Relationships for orthophosphate and nitrate from annual means and a statistical modelling approach are compared in the Appendix C: overall conclusions are not dependent on the choice of analysis approach for this dataset.

Trends for bioavailable metals (lead, nickel, copper and zinc) plus cadmium from 2014 onwards are also provided in the interim Defra 25 Year Environment Plan H4 indicator report: Exposure and adverse effects of chemicals on wildlife in the environment: interim H4 indicator. The data used includes all HMS sites but also a much wider range of Environment Agency river monitoring sites. Trends in average metal concentrations in river waterbodies polluted by abandoned metal mines are reported separately from other rivers. Since 2014, (bioavailable) metal concentrations in the rivers polluted by abandoned metal mines are reported as stable or slightly increasing. In other rivers, concentrations are reported as decreasing. As part of the H4 indicator, further work is being undertaken to understand trends in bioavailable metals in rivers polluted by abandoned metal mines and the wider population of rivers.

The improvements in lowland river water quality presented here broadly mirror recent analyses of national-scale trends in the macroinvertebrate communities of English rivers (Pharaoh and others, 2023; Qu and others, 2023; Pharaoh and others, 2024). However, more work is needed to relate trends in physico-chemical/chemical quality and biological water quality. Despite these marked improvements in river water quality, we need to continue investment and advice in order to improve water quality further. We also need to continue monitoring and analysis to understand the changes that are occurring.

5. References

LEE, L. AND HELSEL, D. Statistical analysis of water-quality data containing multiple detection limits: S-language software for regression on order statistics. Computers & Geosciences 2005: volume 31 edition (10), pages 1241-1248.

MAYES, W.M. AND OTHERS. Inventory of aquatic contaminant flux arising from historical metal mining in England and Wales. Science of The Total Environment 2010: volume 408, pages 3576-3583.

MILLARD, S.P. EnvStats: An R Package for Environmental Statistics. Springer 2013, page 291.

PHARAOH, E. AND OTHERS. Evidence of biological recovery from gross pollution in English and Welsh rivers over three decades. Science of The Total Environment 2023: volume 878, page 163107.

PHARAOH, E. AND OTHERS. Potential drivers of changing ecological conditions in English and Welsh rivers since 1990. Science of The Total Environment 2024: volume 946, page 174369.

QU, Y. AND OTHERS. Significant improvement in freshwater invertebrate biodiversity in all types of English rivers over the past 30 years. Science of The Total Environment 2023: volume 905, page 167144.

SIMPSON, E.A. The harmonization of the monitoring of the quality of rivers in the United Kingdom. Hydrological Sciences Bulletin 1980: volume 25 edition 1, pages 13-23.

WOOD, SIMON, N. Generalized Additive Models: An introduction with R, Second Edition. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2017.

6. Technical appendices

6.1 Appendix A. Note on alterations to graphs: truncated confidence intervals and removed years.

The following table summarises alterations made to graphed upper confidence intervals (Upper CI) to ensure legibility of graphs and removal from graphs of outlying values for ammonia and BOD from 1989 only.

| Determinand | Year(s) | Value trimmed or removed | Trimmed or removed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonia | 1989 | Mean: 2.42 | Year removed from graph |

| BOD | 1989 | Mean: 6.53 | Year removed from graph |

| Arsenic | 1990, 1991 | Upper CIs: 5.75, 8.41 | Upper CI trimmed |

| Chromium | 1990 | Upper CI: 5.97 | Upper CI trimmed |

| Zinc | 2020 | Upper CI: 38.3 | Upper CI trimmed |

6.2 Appendix B. Comparison of metal concentrations on the River Carnon with average data with and without that site.

The following figure illustrates the effect of inclusion/exclusion of the River Carnon on the arithmetic means for copper and zinc from 1990 to 2023. Data for the River Carnon itself are also shown. The results show how the extremely high concentrations of dissolved metals at this one site can alter the annual arithmetic means for the entire dataset of 135 sites. Note that the data are graphed on a logarithmic y-axis scale and the 2 graphs use different y-axis scales.

Figure 7. England HMS sites: Effect of inclusion (All sites) and exclusion (Without Carnon) of the River Carnon on the arithmetic means for copper and zinc from 1990 to 2023. Data for the Carnon itself also shown.

6.3 Appendix C. Comparison of annual arithmetic mean concentration with geometric mean trend based on statistical modelling.

Alongside trends in annual arithmetic means (calculated using the regression on order statistics approach described above), trends have also been derived using a statistical modelling approach. Generalised additive mixed models (Wood, 2017) were fitted to the temporal data for each determinand, either using sample date (converted to a decimal) with a cubic regression smooth, or sample year treated as a random effect. Other covariates were sample month – modelled using a cyclic spline and site identity as predictor variables. Each concentration value was log10-transformed prior to modelling, and values below detection limit were specified as being anywhere between zero and the detection limit for that measurement, assuming a censored normal family for the log-transformed data. The model was then used to predict mean concentrations (excluding the site identity and month component) for each year from 1980 (or 1990 for metals), with 95% confidence interval, finally the resulting predictions were untransformed to the original concentration scale. As the models were fitted to log-transformed data, this approach describes the overall geometric mean rather than arithmetic mean. It also correctly considers the lack of independence in the data arising from the same sites being repeatedly sampled over time. This is achieved through treating site identity as a random intercept in the model. The method also accounts for any characteristic seasonality in the data (some seasonality is present for each determinand), is not sensitive to bias arising from missing sites or samples and (like the annual means approach used above) treats values recorded as below the limit of detection correctly.

Results of this alternative approach are not shown in full because for all determinands except nitrate, the patterns of trends in modelled geometric mean concentrations were very similar to those for arithmetic means, although the confidence intervals differed. For nitrate, there are slight differences in trends between the 2 approaches, described below.

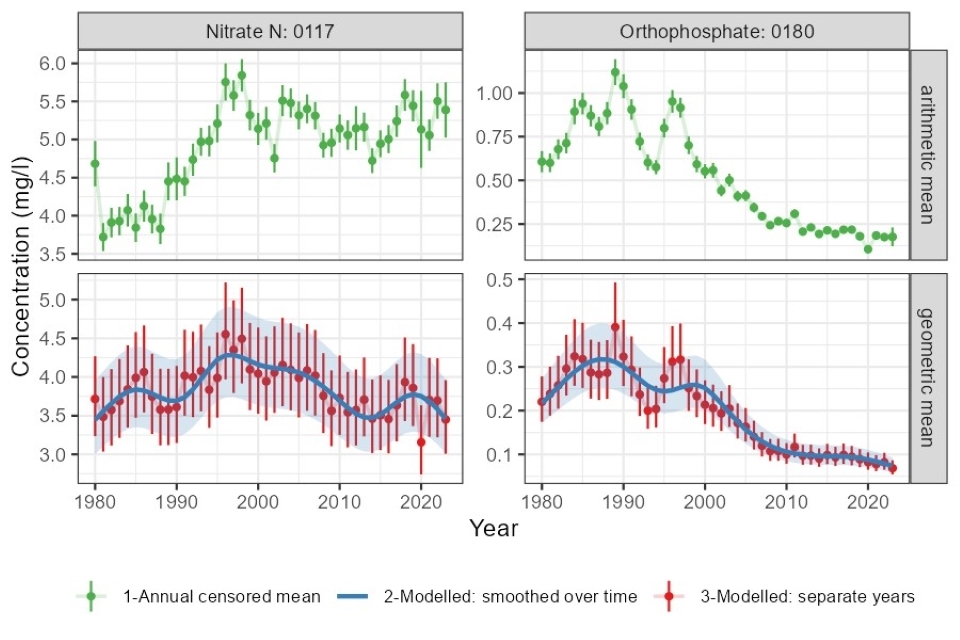

The following figure compares the temporal trends for nitrate and orthophosphate described in the main report (annual arithmetic censored means – identified in green in the upper panels) with 2 variants of the trend derived using the statistical modelling approach. In each case, the overall mean trend is shown alongside the 95% confidence interval for that mean. The 2 relationships shown in the lower panels are both variations of the modelling approach: firstly, the temporal trend smoothed over time, to emphasise the long-term pattern (blue line) and secondly, not smoothed over time, instead treating the years separately as a random intercept term (additive with the random effect for site). This latter approach places greater emphasis on shorter-term (inter-annual) variations in concentration.

Figure 8. England HMS sites: Comparison between the temporal trends for nitrate and orthophosphate from 1980 to 2023

The comparison shows that in each case, geometric means are lower than arithmetic means; this is consistent with the typical lognormal behaviour of concentration data. For orthophosphate, the 2 approaches give similar results, describing the rise in concentrations up to 1989 and then a fall up to the present day. For nitrate, the trends do initially appear somewhat different. However, in the context of the overall range of the predictions, both approaches generally indicate that, compared to the other determinands considered in this report, nitrate concentrations at the 135 Harmonised Monitoring Scheme sites for England have changed relatively little over the period from 1980 to 2023. For both determinands, the 95% confidence intervals for the annual arithmetic means are narrower than those of the modelling approach. This suggests that it is important to account for the lack of independence present in the data where sites are monitored repeatedly over time; doing so leads to wider confidence intervals.