Young people's substance misuse treatment statistics 2019 to 2020: report

Updated 10 June 2021

Applies to England

1. Main findings

1.1 Trends in young people’s treatment numbers

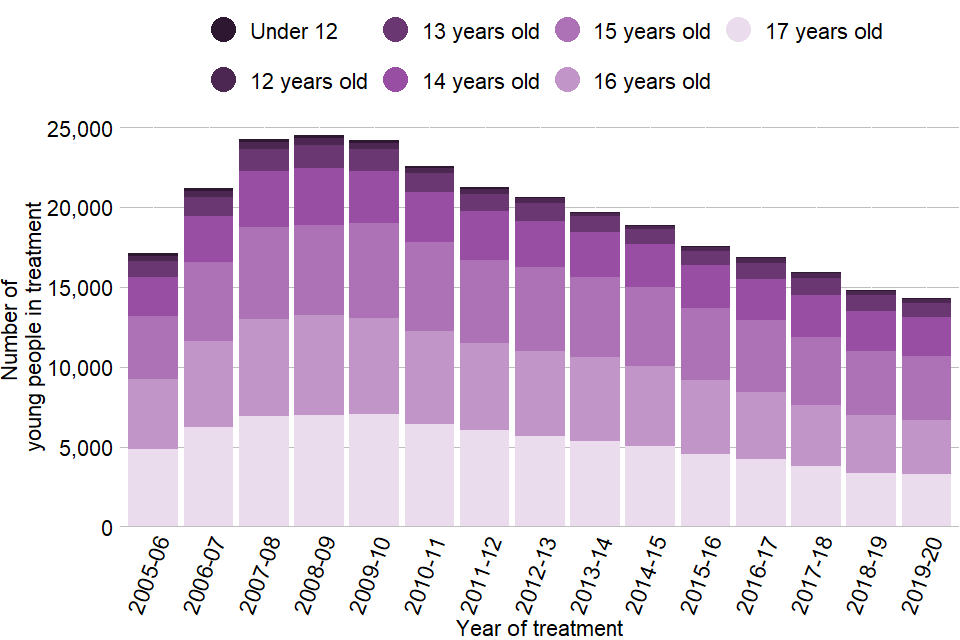

There were 14,291 young people in contact with alcohol and drug services between April 2019 and March 2020. This is a 3% reduction on the number the previous year (14,777) and a 42% reduction on the number in treatment since 2008 to 2009 (24,494).

1.2 Trends in young people’s substance use

Cannabis remains the most common substance (89%) that young people come to treatment for. Similar proportions of young people in treatment who use cannabis have been recorded in the last 3 years.

Around 4 in 10 young people in treatment (42%) said they had problems with alcohol (compared to 44% the previous year), 13% had problems with ecstasy and 10% reported powder cocaine problems.

There was a slight decrease in the number of young people seeking help for heroin (51 compared to 57 last year), which is less than 1% of those in treatment.

There was a 19% decrease from the previous year in young people reporting a problem with benzodiazepines. However, the number in the latest year was more than double the number in 2016 to 2017.

1.3 Vulnerabilities among young people in treatment

The most common vulnerability reported by young people starting treatment was early onset of substance use (76%), which means the young person started using substances before the age of 15. This was followed by poly-drug use (56%).

Proportionally, girls tended to report more vulnerabilities than boys, particularly self-harming behaviour (31% compared with 10%) and sexual exploitation (10% compared with 1%).

1.4 Mental health treatment need

More than a third (37%) of young people who started treatment this year said they had a mental health treatment need, which is higher than last year (32%). A higher proportion of girls reported a mental health treatment need than boys (49% compared to 30%).

Most young people (68%) who had a mental health treatment need received some form of treatment, usually from a community mental health team.

1.5 Treatment exits

Of the young people who left treatment, 82% left because they successfully completed their treatment programme, which is slightly higher than the proportion the previous year (81%). The next most common reason for leaving treatment (12%) was leaving early or dropping out, which was slightly lower than the previous year (13%).

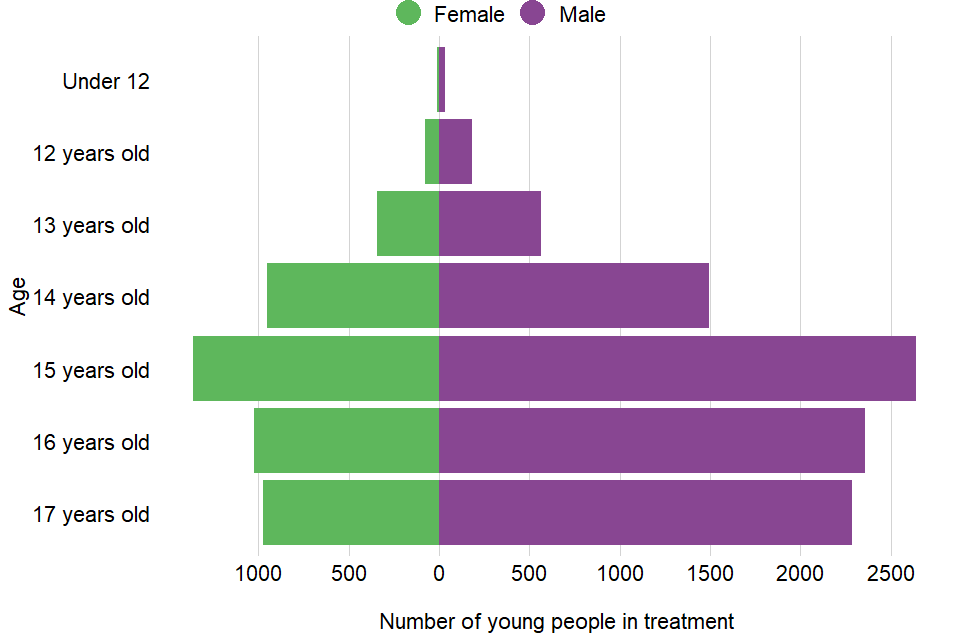

2. Age and sex of young people in treatment

There were 14,291 young people in contact with drug and alcohol services between 1 April 2019 and 31 March 2020. Two-thirds were male (67%), which was similar to the previous 2 years. The median age was 15 years old for both boys and girls. The number of younger children (under 14) in treatment remained relatively low (1,204, 8%).

Figure 1: Age and sex of young people in treatment

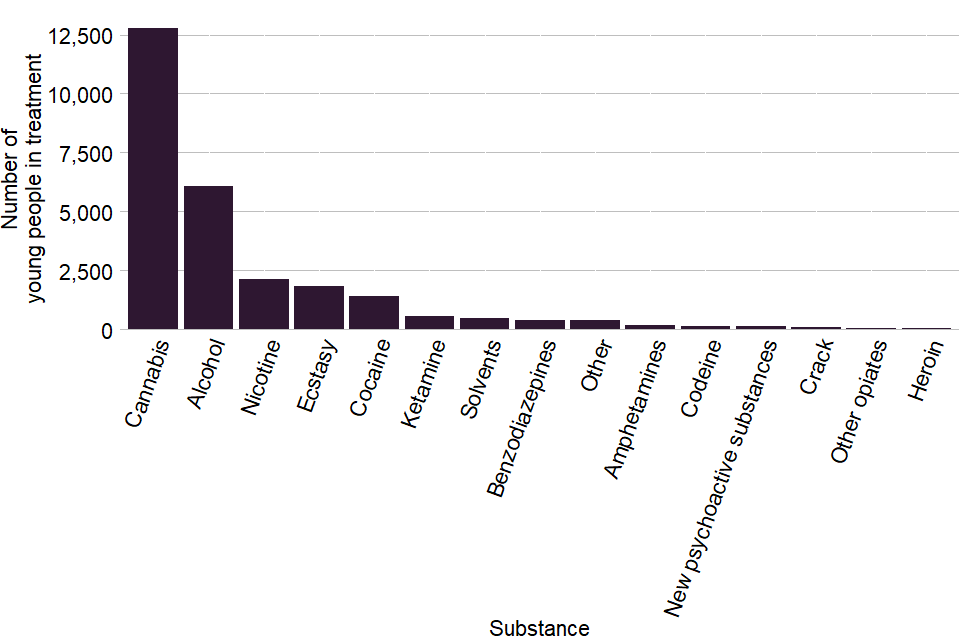

3. Substance use by young people

When young people enter treatment, they can record up to 3 substances that they have a problem with. Numbers in this section are based on all substances recorded during their treatment.

There were 12,775 young people who said they had a problem with cannabis (89% of all in treatment), while 6,060 (42%) said they had a problem with alcohol.

Thirteen per cent (1,836) said they had a problem with ecstasy and 10 % (1396) reported a problem with powder cocaine.

Figure 2: Problematic substance use by young people

The trends section of this report shows the breakdown by substances since 2005 to 2006.

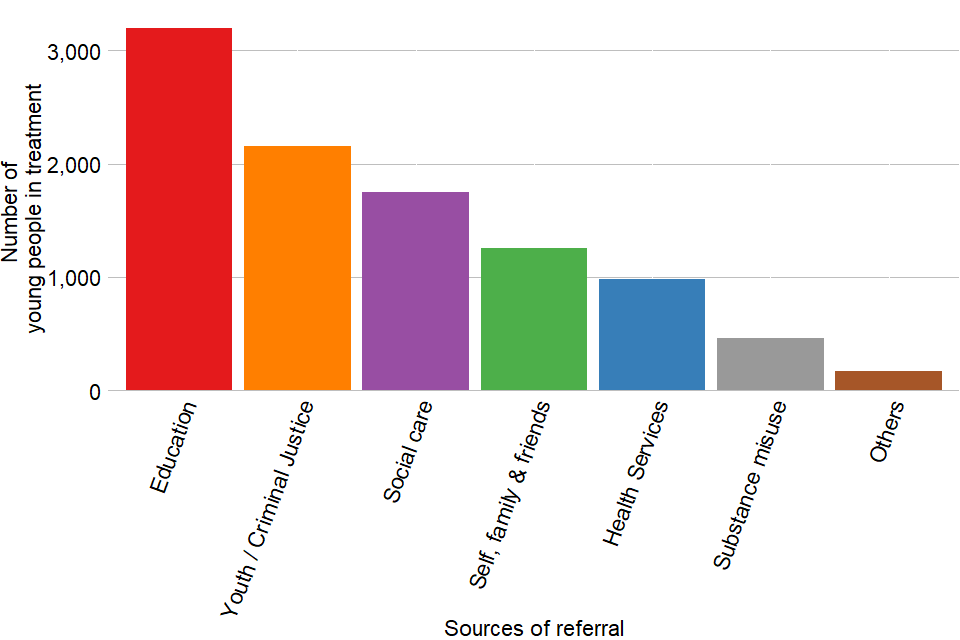

4. Referral routes into treatment

The most common route for young people to get into specialist treatment services was a referral from education services (such as mainstream education or alternative education). There were 3,196 (32%) young people who entered treatment this way.

Referrals from the youth justice system were the second largest source of referral (22%). Social care services accounted for 18% of referrals. Other routes included referral by self, family or friends (13%), health services (10%) and substance misuse services (5%).

Figure 3: Referral routes into treatment

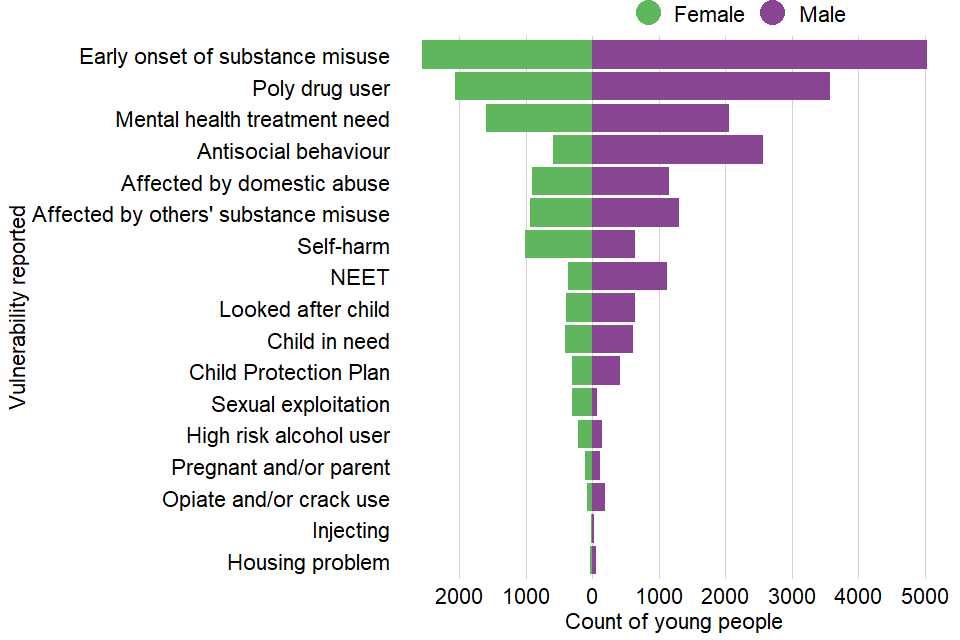

5. Vulnerabilities of young people in treatment

Young people often enter specialist substance misuse services with a range of problems or vulnerabilities related to (or in addition to) their substance use. These include using multiple substances, having a mental health treatment need, being a looked after child or not being in education, employment or training (NEET). Other wider risk factors can also impact on their substance use, such as self-harming behaviour, sexual exploitation, offending or domestic abuse.

Vulnerabilities are reported here only for young people who entered drug and alcohol treatment services during 2019 to 2020.

The most common vulnerability was early onset of substance use (76%), which means the young person started using substances before the age of 15. This was followed by young people reporting ‘poly-drug use’, meaning that they used multiple substances (56%).

Proportionally, girls tend to report more vulnerabilities than boys, particularly for self-harming behaviours (31% compared with 10%) and sexual exploitation (10% compared with 1%).

Other vulnerabilities that were commonly reported by young people include antisocial behaviour (32%), which was more common for boys than girls (38% compared with 18%), being affected by domestic abuse (21%) and being affected by others’ substance use (22%). Less commonly reported vulnerabilities include opiate or crack use (3%), being pregnant or a parent (2%), housing problems (1%) and injecting (less than 1%). Being involved with social services as a looked after child (10%), a child in need (10%) or having a child protection plan (7%) are also recorded as vulnerabilities.

Figure 4: Vulnerabilities among young people in treatment

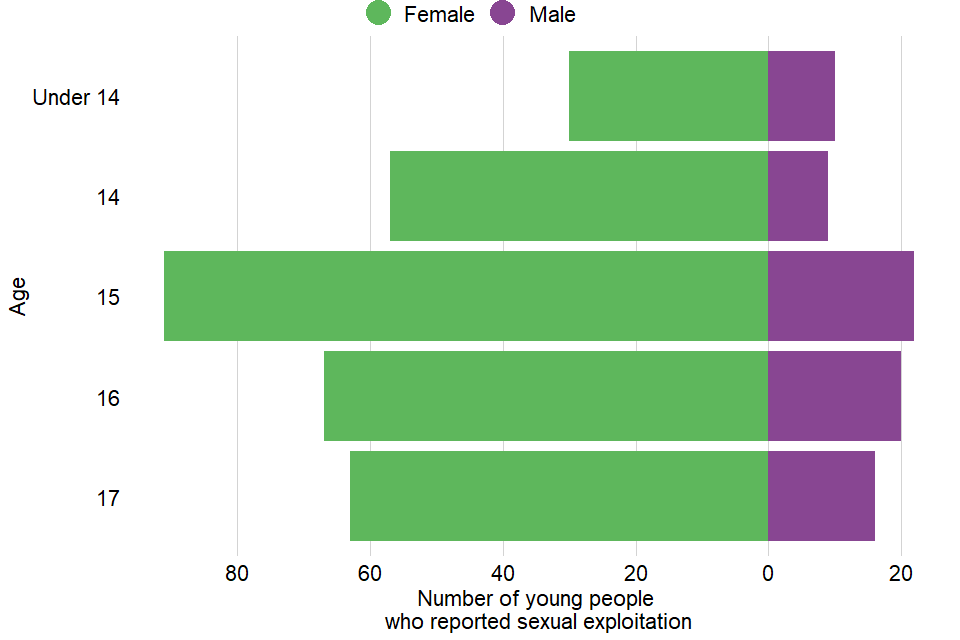

6. Sexual exploitation

The Department for Education has published guidance which defines child sexual exploitation (CSE):

“Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and, or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology.”

Overall, 4% of young people who entered treatment in 2019 to 2020 reported CSE. The proportion was also 4% for each single year of age, except those aged 17, where it was 3%. Among girls, 10% of those aged 15 or older reported CSE compared to 8% of those aged 14 or younger. For boys, the proportion reporting CSE was around 1% for both these age groups.

Figure 5: Sexual exploitation of young people in treatment

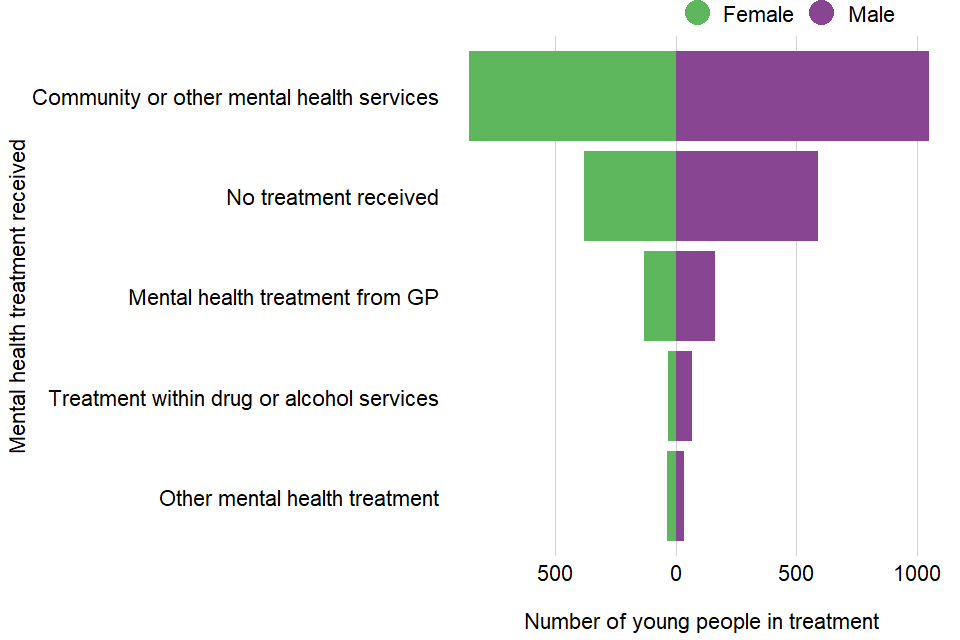

7. Mental health needs

Over a third (37%, 3,659) of young people who started treatment in 2019 to 2020 said they needed mental health treatment.

A higher proportion of girls reported a need for mental health treatment than boys (49% compared to 30%). Of those reporting a mental health treatment need, 68% were receiving some form of mental health treatment.

Overall, a slightly higher proportion of girls who needed mental health treatment received a form of mental health treatment compared to boys (69% compared to 67%).

The most common treatment type was from community or other mental health services (54%). Smaller numbers received mental health treatment from a GP (9%) or mental health treatment within drug or alcohol services (3%). Thirty-two per cent received no treatment.

Figure 6: Mental health needs of young people in treatment

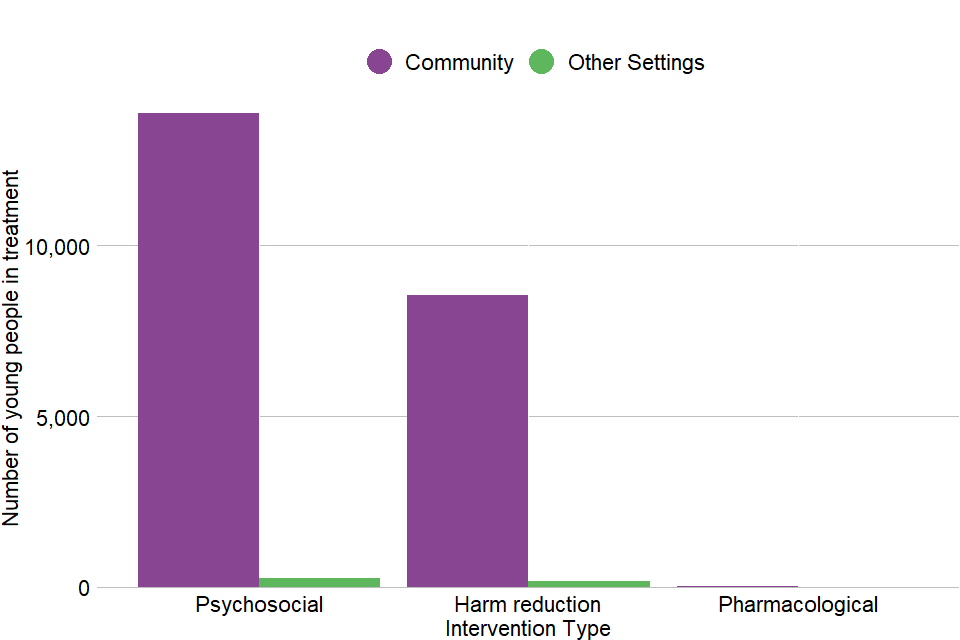

8. Treatment types

Almost all young people who started a drug or alcohol treatment intervention received psychosocial interventions during their time in treatment (14,073). These types of interventions (also known as ‘talking therapies’) use psychological, psychotherapeutic and counselling skills to encourage behaviour change.

Structured harm reduction interventions include support to manage risky behaviours associated with substance misuse, such as overdose or accidental injury. In 2019 to 2020, 8,685 young people (62%) received these interventions.

Only 35 young people (less than 1%) received a pharmacological intervention during treatment. These interventions involve medication prescribed by a clinician and can include detoxification, stabilisation, relapse prevention, and substitute prescribing for opiates.

The vast majority of young people who had these interventions received them in community services (99%). A small number received them in other settings, such as at home, a residential setting, an adult setting or an inpatient unit.

Figure 7: Treatment types received by young people

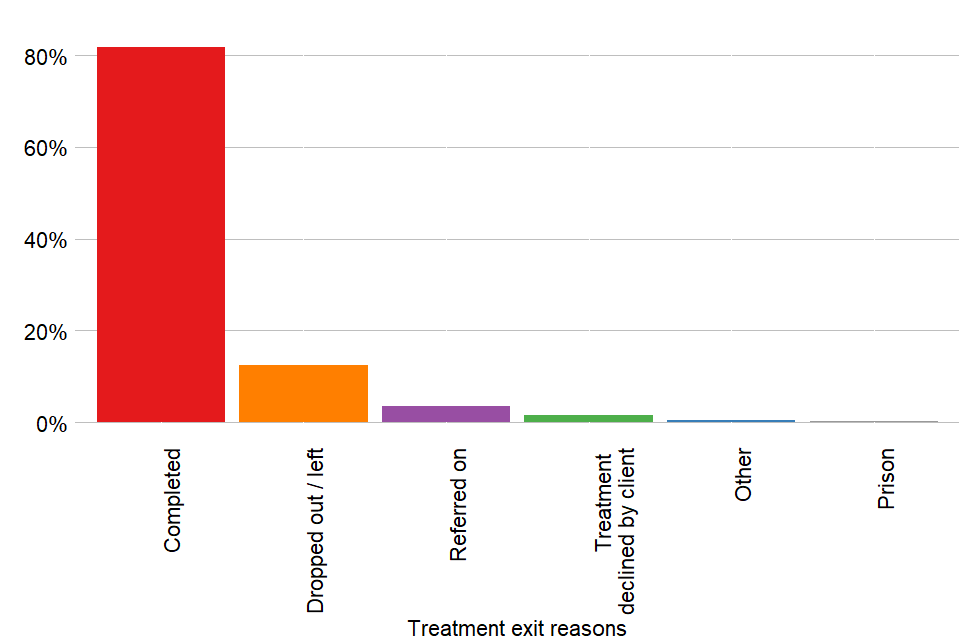

9. Treatment exits

Over two-thirds (68%, 9,731) of young people left treatment in 2019 to 2020. Of those who left, 7,960 (82%) young people successfully completed their treatment and 1,208 (12%) dropped out. A further 4% were referred to another provider for treatment and 1% declined the treatment offered.

Figure 8: Treatment exit reasons

10. Trends over time

Methodological note: the method for counting young people in treatment has changed for this report (2019 to 2020). Data for previous years has been revised with the new method, so some numbers in this section will be different from numbers published in previous reports.

10.1 Trends in age and numbers in treatment

The number of young people attending specialist substance misuse services has fallen year-on-year since a peak of 24,494 in 2008 to 2009. The number of young people attending services during 2019 to 2020 is 42% lower than this peak and 3.3% lower than the number in treatment in the previous year.

Since the peak in 2008 to 2009, there has been a greater decrease in the number of 16 and 17 year olds in treatment than those aged 15 or younger (44% decrease compared to 35%). As a result, the proportion of all young people in treatment who are aged 15 or younger has increased, from 46% in 2008 to 2009 to 54% this year.

Data from the Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use among Young People in England survey showed a long-term decreasing trend in the proportion of school pupils reporting lifetime drug use until 2014. However, there was a significant increase in this proportion in 2016 and it remained similar in 2018.

Figure 9: Trends in age and numbers in treatment

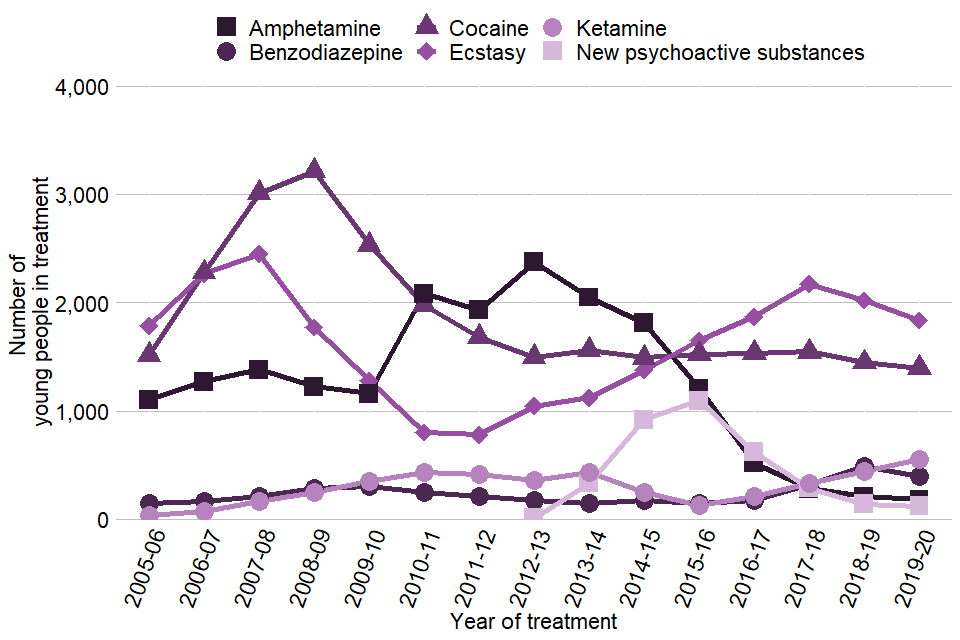

10.2 Trends in recorded substance misuse

The proportion of young people in treatment who said that they had problems with cannabis has increased slightly since 2018 to 2019 to 89%. The proportion who reported having alcohol problems has fallen steadily from a peak of 68% in 2008 to 2009 to 42% in 2019 to 2020.

Figure 10: Trends in substance misuse

There was a 9% reduction in the number treated for ecstasy in 2019 to 2020 compared to the previous year (from 2,021 to 1,836). However, this was more than double the number in 2012 to 2013 (780). There is a long trend of reduction in young people in treatment for amphetamine use, from a peak of 2,375 in 2012 to 2013, to 182 this year.

Cocaine use among young people in treatment peaked in 2008 to 2009 (3,213), falling to 1,494 in 2012 to 2013. Since this point, the number has remained similar year-on-year (1,396 this year).

The number of young people reporting new psychoactive substances has also continued to fall, from a peak of 1,094 in 2015 to 2016 to 120 in 2019 to 2020. The number of young people in treatment for ketamine problems has increased to 549, compared to 440 in the previous year.

The number of young people who reported benzodiazepines as a problematic substance has decreased by 18% (from 489 to 397). However, this was more than double the number in 2016 to 2017 (170).

There was a slight decrease in the number of young people seeking help for heroin (51 compared to 57 last year), and this number has reduced by 95% since its peak in 2005 to 2006 (984). However, there have been recent increases in young people getting help for codeine (another opiate), with 142 this year, more than 3 times the number in 2016 to 2017 (39).

The number of young people reporting solvent use has increased by 19% this year (from 394 to 469). This was the highest number reported since 2011 to 2012 (477).

The data tables for this year’s young people’s substance misuse treatment statistics also contain trends by the ‘primary substance’. This is the main substance that the young person reported problems with when they entered treatment.

11. Background and policy context

11.1 Background to the data

This report presents statistics on the availability and effectiveness of young people’s alcohol and drug treatment in England and the profile of those accessing this treatment.

The statistics in this publication come from analysis of the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS). The NDTMS collects data from sites providing structured substance misuse interventions to young people in every local authority in England.

The data collected includes information on the demographics and personal circumstances of young people receiving treatment, as well as details of the interventions delivered and their outcomes.

You can find more details on the methodology used in the report in the NDTMS annual statistics quality and methodology information paper.

11.2 Policy context

Specialist substance misuse services for young people are normally separate from adult treatment services because young people’s alcohol and drug problems tend to be different to adults and need a different response. This includes being child-centred, considering the age and maturity of young people, acting on safeguarding concerns and making sure the young people do not mix with adult drug users.

These services support young people, help them to reduce the harm their alcohol or drug use causes them and try to prevent it from becoming a bigger problem as they get older. Services should be part of a wider network of local prevention services, which support young people with a range of issues and help them to build their resilience.

Young people’s alcohol and drug treatment in England is commissioned by local authorities using the public health grant. They are responsible for assessing local need for treatment and commissioning a range of services and interventions to meet that need.

The public health grant conditions make it clear that:

“A local authority must, in using the grant: have regard to the need to improve the take up of, and outcomes from, its drug and alcohol misuse treatment services.”

Public Health England (PHE) works with local authorities and provides them with bespoke data, guidance, tools and other support to help them commission services more effectively.

PHE guidance for alcohol and drug treatment is available in the Alcohol and drug misuse prevention and treatment guidance collection.

A wide range of NDTMS data is available on the NDTMS website, including some data reports that are only available to local authority commissioners (via login).

The government’s strategy for drug treatment and prevention is set out in the ‘reducing demand’ and ‘building recovery’ sections in the Drug Strategy 2017.

Young people’s substance misuse services need to ensure that they are responding appropriately to child sexual exploitation. PHE has published guidance on how public health leaders can prevent and intervene early in cases of child sexual exploitation.