Country policy and information note: humanitarian situation, Sudan, February 2024 (accessible)

Updated 4 February 2025

Executive summary

Violent conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Response Forces (RSF) broke out on 15 April 2023. This has created a humanitarian situation in the country which is said to be dire.

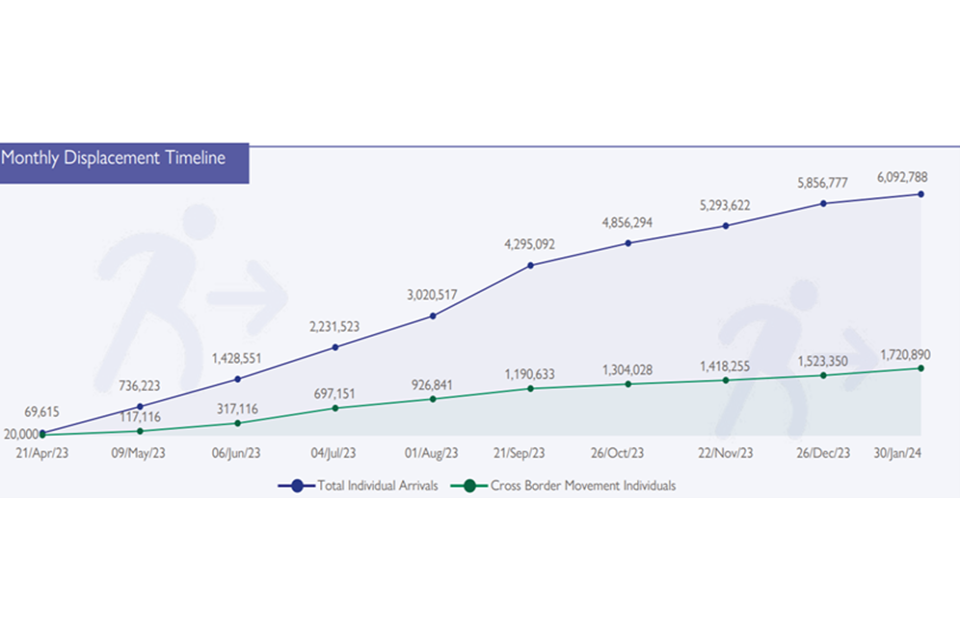

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs noted that 24.7 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance compared to 15.8 million before the outbreak of the conflict (a 57% increase). The fighting has displaced a total of 7.8 million people – 6.1 million internally and 1.7 to neighbouring countries - as at 30 January 2024. Prior to the conflict, Sudan had over 3 million internally displaced people thus bringing the total number of displaced people to 10.7 million according to the International Organization for Migration Displacement Tracking Matrix. In addition, over 13,000 people have died in Sudan since the conflict started.

There have been widespread and indiscriminate attacks on civilian infrastructure while insecurity, bureaucratic access impediments, looting, attacks against humanitarian premises and warehouses, and lack of fuel have hampered humanitarian access and delivery. Despite the challenges, 163 humanitarian organisations have provided multisectoral life-saving assistance to 4.9 million people as well as agriculture and livelihood support to 5.7 million people since the start of the conflict.

In general, the humanitarian situation in Khartoum, Darfur, Kordofan, Al Jazira and Sennar (which have experienced the most intense fighting) is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment as set out in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 ECHR. The humanitarian situation tends to be relatively better in states further away from active hostilities. However, the situation remains fluid while the conflict is ongoing.

Humanitarian needs vary across the country, tending to decrease in severity the further away a person resides from the active hostilities. However, the displacement of populations to states that are currently less affected by the conflict has led to significant burden on humanitarian assistance in those areas.

In general, internal relocation may be possible to those regions less affected by direct fighting but this can change at any time due to the volatility of the situation with previously peaceful states becoming the centre of fighting as seen in the case of Al Jazira and Sennar. Each case will need to be considered on the most current information. There are parts of the country under government control, particularly the east, where it will be reasonable for a person to relocate.

Freedom of movement both within and from and to the country is severely limited by the fighting, insecurity due to banditry and other criminality along the roads, high fuel costs and closure of the commercial airspace. This may affect the ability to relocate.

Assessment

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is information in the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

- that the general humanitarian situation is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

- a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

- a grant of asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave is likely, and

- if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3. In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: not for disclosure – start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: not for disclosure – end of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: not for disclosure – start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: not for disclosure – end of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 A severe humanitarian situation does not of itself give rise to a well-founded fear of persecution for a Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.2 Without a link to one of the 5 Refugee Convention grounds necessary to be recognised as a refugee, the question to address is whether the person will face a real risk of serious harm in order to qualify for Humanitarian Protection (HP) (see the Asylum Instruction on Humanitarian Protection).

2.1.3 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3.Risk

3.1.1 The humanitarian situation varies from state to state. Conditions in the centre, south and west of the country – specifically in Khartoum, Darfur and Kordofan as well as Gezira and Sennar, where fighting is concentrated – are likely to be so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is in general a real risk of serious harm as set out in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 ECHR.

3.1.2 Conditions decrease in severity with distance from the active hostilities. In general, they are unlikely to breach Article 3 in the east of the country, including Red Sea, River Nile, Kassala, and Blue Nile states, where fighting has been less intense. However, the situation remains volatile with fighting spreading to the east. Each case must be considered on its individual facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate that they face a real risk of serious harm.

3.1.3 Since April 2023, Khartoum and neighbouring towns, including Omdurman and Bahri, as well as the Darfur states and North Kordofan state, have been the epicentres of the fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Response Forces (RSF). As at December 2023 the fighting had spread eastwards to Al-Jazirah and Sennar. The fighting has led to the occupation, destruction and looting of health and humanitarian facilities and warehouses; suspension of humanitarian operations and adversely affected humanitarian access (for more detail about the location of the conflict and an assessment of risk as a result of indiscriminate violence, see the country policy and information note, Sudan: Security situation).

3.1.4. The civil conflict has made an already poor economic situation worse. As at October 2023 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook noted that the inflation rate (average consumer price) rose from 138.8% in 2022 to 256.2% in 2023, unemployment rose from 32.1% in 2022 to 46% in 2023; Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita dropped from US$ (current prices) 723.03 in 2022 to US$ 533.85 in 2023, and real GDP growth fell from -2.5% in 2022 to -18.3 % in 2023. The World Bank estimates that approximately 33% of the population are living in extreme poverty, which it defines as income of less than US$2.15 per day at 2017 prices. The Central Bank of Sudan and local commercial banks in conflict areas have closed, leaving people without access to cash and financial assets.

3.1.5 According to the UN Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) revised Humanitarian Response Plan for Sudan, the number of people in need of some form of humanitarian assistance increased from 15.8 million before the conflict to 24.7 million in May 2023, around half the population (see Economic situation and People in need).

3.1.6 The World Food Programme estimated that approximately 19 million (40%) of the population are acutely food insecure, with the levels of insecurity highest in West Darfur (64%), West Kordofan (64%), Blue Nile (57%), Red Sea ((56%) and North Darfur (54%). Humanitarian organisations have provided food assistance in at least 14 states since the start of the conflict (see Food security).

3.1.7 The OCHA estimated that 19.9 million were in need of water and sanitation, with crumbling infrastructure leaving 17.3 million people without access to basic level drinking water supply and approximately 24 million without access to proper sanitation facilities. Support agencies targeted 6.1 million for WASH assistance, with at least 4 million reached since the conflict started (see Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)).

3.1.8 The healthcare situation remains dire due to attacks on health facilities, lack of medical supplies and insecurity preventing access, particularly in conflict areas. OCHA reported that about 70% to 80% of health facilities in conflict affected areas are non-functional. The World Health Organisation (WHO) documented 60 verified attacks on health facilities, 34 deaths and 30 injuries between 15 April and 14 December 2023 compared to 23 attacks, 7 deaths and 4 injuries in the whole of 2022 (see Healthcare). Health care is also strained in states not directly affected due to the influx of displaced people. Approximately 11 million people were in need of health assistance with 7.6 million targeted for assistance. As at 31 December OCHA stated humanitarian organisations had reached 24% of those targeted for assistance (see Assistance in healthcare).

3.1.9 The conflict has led to the destruction of housing, household assets and public infrastructure. An estimated 5.7 million are in need of shelter and non-food items assistance with 1.9 million targeted for assistance. OCHA reported that in 2023 since the beginning of the year, cluster partners have provided diverse forms of shelter and Non Food Items assistance to 603,695 Sudanese people and 282,215 refugees received shelter and Non Food Items NFI assistance. The figures include 439,575 IDPs, returnees and vulnerable residents in 18 States and 211,880 refugees that received assistance since April 2023 (see Provision of Shelter and NFI).

3.1.10 The fighting has severely impacted education. Schools and educational institutions remain closed in the conflict-affected areas including Khartoum, Al Jazirah, South Darfur, West Darfur and West Kordofan. According to OCHA, as of November 2023 the conflict had deprived about 12 million children of schooling since April, with the total number of children in Sudan who are out of school reaching 19 million. Of this total, 6.5 million children have lost access to school due to increased violence and insecurity, with at least 10,400 schools now closed in conflict - affected areas. Schools are also used to shelter IDPs (see Education). US$131.0 million was required to assist 4.3 million out of the 8.6 in need of educational assistance. At the end of November only US$ 27.0 million (or 20.6%) of the required funding had been received. Only 87,433 [or 2%] of the 4.3 million targeted children had been reached with assistance.

3.1.11 The International Organization for Migration Displacement Tracking Matrix reported noted that as of 30 January 2024 the conflict has displaced 7.8 million people – 6.1 million internally and 1.7 million mixed population to neighbouring countries (see Total displacement). The vast majority of the displaced are from Khartoum (64.9%) while South Darfur hosts the highest number of IDPs (12.9 % of total IDPs). For information of states producing and hosting IDPs see in other states see (see Internally displaced people (IDPs).

3.1.12 Sudan has received hundreds of millions of pounds from the international community to support ongoing humanitarian needs, however according to the Financial Tracking Services (FTS), as of February 2024, US$1.11 billion (43.1%) of the US$2.6 billion required funding had been received leaving a funding gap of US$1.46 billion (56.9% (see Funding).

3.1.13 Insecurity, targeted attacks on aid workers, aerial bombardments, roadblocks, movement restrictions have constrained humanitarian access to food, water, healthcare and education in conflict areas. Infrastructure damage has led to internet and electricity blackouts and fuel, water, and food shortages, creating logistical challenges for humanitarian operations. The humanitarian mission in Wad Madani, Al Jazira state has been suspended since December 2023. Shelling and aerial bombardments in the outskirts of Sennar also remains a significant challenge. Displacement into states less affected by direct conflict has also constrained the humanitarian situation there (see Access to humanitarian assistance).

3.1.14 However, from April to November 15th, 163 humanitarian agencies gave 4.9 million people humanitarian help. With 376,300 out of 563,600 (or 67%) targeted people assisted. For information of number of people assisted in each state see Provision of assistance).

3.1.15 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Internal relocation

4.1.1 Internal relocation may be possible in areas not directly affected by conflict, such as Red Sea, River Nile, Northern and White Nile states. Some internally displaced populations (IDPs) have self-relocated in search of safety. However, the situation remains fluid with fighting being reported in previously unaffected states such Al Jazirah, Sennar, River Nile, Gedaref, Kassala and Red Sea. There are parts of the country under government control, particularly the east (for information on areas under government control see Security situation) where it will be reasonable for a person to relocate. However, Each case must be considered on its facts and in light of most current information.

4.1.2 Relocation from or through a conflict-affected areas is unlikely to be reasonable. Persons would need to return to an area or city not affected by the conflict, such as Port Sudan, then, if not remaining in the city, relocate from there. However, since the outbreak of the conflict freedom of movement has been limited in practice due to conflict-related risks. Road and airport closures due to the fighting have restricted people’s movement away from conflict-affected areas to seek safety and access humanitarian aid and other services. In addition, scarcity of fuel, banditry, criminality, and illegal checkpoints have impeded movement (see Freedom of Movement and country policy and information note, Sudan: Security situation).

4.1.3 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5.Certification

5.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

5.1.2. For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content of this section follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

6. Geography and administrative division

6.1.1 For information on geographic location, size and administrative divisions of Sudan see Country and information note: Security situation Sudan, June 2023.

6.2 Population size

6.2.1 A May 2023 report by CARE International (CI report May 2023) noted: ‘Population data for Sudan is difficult to glean from secondary data as the last official census was in 2008’. It then stated that ‘Sudan has a total population of 49.7 million with an annual growth of 2.75%.’[footnote 1] US CIA Factbook updated 13 December 2023 estimated Sudan’s 2023 population to be 49,197,555.[footnote 2] The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Data Exchange (OCHA HDX 2023), estimated Sudan’s population (excluding refugees) at the end of 2022 to be 48,748,901 and (including refugees) to be 49,887,897.[footnote 3].

6.2.2 CPIT has produced below table based on OCHA HDX 2023 data that shows Sudan’s population by state.[footnote 4]

| State | Population (including refugees | Population excluding refugees |

|---|---|---|

| Abyei PCA | 250,000 | 250,000 |

| Al Jazirah | 5,705,029 | 5,687,557 |

| Blue Nile | 1,357,645 | 1,344,267 |

| Central Darfur | 1,797,765 | 1,786,503 |

| East Darfur | 1,313,743 | 1,213,951 |

| Gedaref | 2,613,485 | 2,545,604 |

| Kassala | 2,922,045 | 2,811,446 |

| Khartoum | 9,452,977 | 9,146,191 |

| North Darfur | 2,806,903 | 2,775,652 |

| North Kordofan | 2,170,273 | 2,160,476 |

| Northern | 1,024,332 | 1,023,194 |

| Red Sea | 1,556,251 | 1,549,857 |

| River Nile | 1,655,605 | 1,651,873 |

| Sennar | 2,180,763 | 2,170,863 |

| South Darfur | 3,963,470 | 3,912,372 |

| South Kordofan | 2,061,243 | 2,017,962 |

| West Darfur | 1,941,286 | 1,940,860 |

| West Kordofan | 1,786,309 | 1,713,462 |

| White Nile | 3,328,773 | 3,046,811 |

| Total | 49,887,897 | 48,748,901 |

6.3 Demographic profile

6.3.1 CPIT has produced the below table based on data from CIA world Fact book and UN Population division portal showing basic demographic indicators.

| Factor | Data |

|---|---|

| Population growth rate | 2.55% (2023 estimates)[footnote 5] |

| Population (total) | 48 to 49.2 million (2023 estimate)[footnote 6] [footnote 7] |

| Life expectancy | 66.1 years (2023) estimate) [footnote 8] |

| Total fertility rate (per woman) | 4.32 (2023 estimates) [footnote 9] |

| Birth rate | 33.3 births /1000 population (2023)[footnote 10] |

| Death rate | 6.2 deaths/1000 population (2023)[footnote 11] |

| Maternal mortality rate (deaths per 100,000 live births) | 295 (2023 estimates) [footnote 12] |

| Infant mortality rate (per 1,000 live births) | 37.5 (2022) [footnote 13] or 41.4 (2023) [footnote 14] |

| Literacy rate (age 15 and older) | Total: 60.7%; male 65.4%, female 56.1% (2018)[footnote 15] |

6.3.2 With respect to ethnicity, US CIA Factbook December 2023 noted that Sudan has over 500 ethnic groups with Sudanese Arabs making up approximately 70% of the population. Other major ethnic group are Fur, Beja, Nuba, Ingessana, Uduk, Fallata, Masalit, Dajo, Gimir, Tunjur, Berti. Arabic and English are the official languages and a majority of the population is Sunni Muslim with a small Christian minority.[footnote 16]

7. Economic situation

7.1 Overview

7.1.1 An April 2022 report by Acaps, an independent information supplier providing humanitarian analysis[footnote 17], noted:

‘Sudan has been facing a socioeconomic crisis caused by the unstable political situation that followed the widespread demonstrations against the politics of former president Omar Hassan al-Bashir in April 2019. The military takeover of the transitional government in October 2021 has further deteriorated the economic situation in Sudan as it resulted in the suspension of international aid, on which Sudan has been depending. Since October 2021, the Sudanese pound has lost about a third of its value, inflation rates have been increasing, there have been shortages of hard currency, and there are no sufficient foreign reserves.’[footnote 18]

7.1.2 A March 2023 report by the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), a leading provider of early warning and analysis on acute food insecurity around the world[footnote 19] noted: ‘Sudan’s economic conditions remain poor as low foreign currency reserves and currency depreciation result in high inflation rates and conflict and political instability disrupt business activity … The ongoing depreciation of the currency is causing the prices of imported goods, including agricultural inputs, to remain at very high levels and is generally contributing to the very high cost of living.’[footnote 20]

7.1.3 A report by the Gender, Growth and Labour Markets in Low Income Countries Programme (G2LM/LIC) published in September 2023 and based on various sources noted: ‘The challenges Sudan has experienced since 2018 have wreaked havoc with its economy. Sudan was reclassified from a lower middle-income country to a low-income country in 2019. The growth of its GDP has been negative since 2018, averaging -2.3% per annum over 2018-2022. Per capita GDP fell by an average of 5.4% per annum from 2018 to 2021 and by 3.0% per annum on average since the 2012 …’[footnote 21]

7.1.4 A 4 October 2023 WB press release noted ‘… In Sudan, economic activity is expected to contract by 12% because of the internal conflict, which is halting production, destroying human capital, and crippling state capacity.’[footnote 22]According to IMF World Economic Outlook report 2024, Sudan’s economic growth rate was -18.3% and was projected to improve to 0.3% in 2024[footnote 23].

7.1.5 CPIT has produced the below table showing basic economic indicators for Sudan based on IMF data[footnote 24].

| - | 2023 | 2024 (projected) |

|---|---|---|

| Economic growth rate (real GDP) | -18.3 | 0.3 |

| GDP current prices (billion US$) | 25.57 | 25.83 |

| GDP per capita (current US$ ) | 533.85 | 525.73 |

| Inflation rate (average consumer price) | 256.2 | 152.4 |

| Unemployment rate (percentage) | 46% | 47.2% |

| Gross debt (as % of GDP) | 256 | 238.8 |

| Population (millions) | 47.9 | 49.14 |

7.2 Employment

7.2.1 A 2020 report by the International Labour Organisation (ILO report 2020), noted:

‘Among the working age population (15+), 57 per cent of Sudanese are in the labour force, and the remaining 43 per cent of the population is not economically active. Unemployment among women is significantly higher, up to three times that of males. Unemployment is also relatively higher for high-skilled individuals. The educational profile of the unemployed indicates one out of four have a university/tertiary education. Twenty-six per cent of the unemployed persons in the Sudan are in Khartoum, and 44 per cent of them have university/tertiary education. The main source of household livelihoods as reported is the primary sector: crop farming and animal husbandry (45 per cent), wages and salaries (36 per cent), and own business (20 per cent). A smaller portion of households depend on pensions (1 per cent), remittances (3 per cent), and humanitarian aid.

‘… there is a very large informal economy in the Sudan, with a labour force that is characterized by seasonal migration, around 85 per cent of workers engaged in vulnerable employment and 60 per cent of the labour force engaged in subsistence agriculture.[footnote 25]

7.2.2 A September 2022 report by UNICEF noted ‘More than a third of youth aged between 15 and 24 [were] unemployed in 2021, with males being slightly disadvantaged (46% vs 31%).’[footnote 26] As of October 2023, IMF reported that unemployment rate in Sudan was 47.2% compared to 32.1% in 2022.[footnote 27]

7.2.3 A February 2021 report by Challenge Fund for Youth Employment, which ‘was launched in 2019 by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs to create more, better and more inclusive jobs for 200,000 young people in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and North Africa,[footnote 28] noted ‘A significant portion of the Sudanese workers is engaged in the informal sector.’ [footnote 29] An October 2023 report by ILO stated also noted that: ‘Most of Sudan’s employment is self-employment, particularly in agriculture and retail.’[footnote 30]

7.3 Poverty

7.3.1 1. A WB brief for Sudan dated April 2023 noted:

‘There is currently no recent and credible poverty estimate for Sudan. The most recent official estimates of poverty in Sudan are based on the 2014/15 National Household Budget and Poverty Survey. At the time, 61.1% of Sudan’s population had levels of per capita expenditure below the national poverty line. Poverty rates vary significantly across states with above average rates observed in Red Sea state, Kordofan and Darfur. If the world Bank International poverty line is used, the incidence of extreme poverty was 15.3 % equivalent to 5. 6 million Sudanese in 2014.

‘… Projections based on GDP suggest that the share of the population living with less than $2.15 per day has increased consistently in recent years and became more urbanised, reaching 33% in 2023 from 20% in 2018.’[footnote 31]

7.3.2 According to the ADB ‘Sudan Economic Outlook’ report, ‘The poverty rate rose from 64.6% in 2021 to 66.1% in 2022[footnote 32]. The WB defined poverty rate as the ratio of the number of people whose income falls below the poverty line. Poverty data is expressed in 2017 purchasing power parity (PPP) prices. The global poverty line for low income country [to which Sudan belong] is US$2.15[footnote 33].

7.3.3 Multiple sources have highlighted the impact of the current socioeconomic situation on child forced labour, trafficking and forced recruitment. On 2 September 2023 Arab News reported that ‘Child soldiers are being recruited by both sides in Sudan’s ongoing civil war’. The report quoted a journalist based in Nyala town Darfur saying: ‘Severe and widespread poverty has driven many children into the arms of the militias.’’[footnote 34] UNHCR reported in June 2023: ‘In the current disrupted socio-economic situation, the risk of neglect and exploitation of children is on the rise. Deprived from family attention and care, children are even more at risk of being induced into forced labour, recruited into armed groups and even trafficked, especially in East Sudan.’[footnote 35] And on 20 January Al Jazeera reported that a Sudanese activist based in Khartoum said in an interview that: ‘poverty and the constant threat of sexual violence have led to many early marriages.’[footnote 36]

8. Banking

8.1.1 The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) revised Humanitarian Response Plan for Sudan published on 17 May 2023 (OCHA HRP May 2023) noted that large sections of the capital including banks ‘have been looted, damaged, or targeted by rocket attacks. The central bank was set ablaze, and local commercial banks closed and ATMs not functioning, leaving people without access to cash and financial assets.’ The same source, citing NetBlocks, a ‘global internet monitor’[footnote 37] noted that, ‘Internet connectivity has been severely disrupted, operating at only 4 per cent capacity.’[footnote 38]

8.1.2 An August 2023 article by Susanne Jaspars, a Senior Research Fellow at SOAS University of London and Tamer Abd Elkreem, a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology and the Deputy Director of the Peace Research Institute at the University of Khartoum, published by African Arguments, a pan-African platform for news, investigation and opinion,[footnote 39] (Jaspars and Elkreem, August 2023) noted: ‘The banking system has collapsed in parts of the country … [and] many banks closed, so cash withdrawals were no longer possible. Digital money transfers became difficult but have remained possible to a limited extent. For many people, this has affected access to income, savings, remittances, and humanitarian aid.’’[footnote 40]

8.1.3 A December 2023 UNICEF report on the impact of the conflict on service delivery (UNICEF report December 2023) noted:

‘The ongoing conflict poses significant challenges to the banking system, which was already characterized as fragile prior to the conflict. Twelve banks (accounting for 25 per cent of banking system capital) have capital adequacy ratios below the regulatory 12 per cent minimum … The banking sector is highly concentrated; the five largest banks account for 55 per cent of the sector’s total assets. Over half of the bank branches are located in only two states: Khartoum (44 per cent) and Gazira (11 per cent), while the remaining 16 states have 45 per cent of the total bank branches.

‘The key payment systems in Sudan are operated by the [Central Bank of Sudan] CBoS and the Electronic Banking Services (EBS) company, a technical arm of CBoS. The CBoS uses Sudan Real Time Gross Settlement (SIRAG) banking system linking all banks to the central bank… The EBS operates a national switch; where banks can access a range of products and services such as Swift, automated teller machines, points of sale, cards, apps, and billers, and is also the operator of the banking system clearing house. Almost all banks are dependent on EBS for electronic services, except five (Bank of Khartoum, Faisal Islamic Bank, Alsalam Bank, Al Baraka Bank and Omdurman National Bank), that have their own switches…’[footnote 41]

8.1.4 On the impact of the conflict on the banking system the UNICEF report December 2023 observed:

‘… The CBoS electronic data system is housed in the headquarters, while its backup is housed in its Khartoum branch, near SAF general command building and the EBS main data system server is housed in CBoS Khartoum branch, with its backup server located close to the CBoS headquarters. These locations are the epicentre of fighting. The systems became inaccessible shortly after the onset of the conflict, their power supply was cut off, and operating them via generator power was not possible. Bank-to-bank payments were cut off, preventing the transfer of money between accounts because electronic clearance was not functioning. Banks thus were not able to deliver any electronic payment services.

‘The conflict has also resulted in the destruction of banking system infrastructure with significant damage to buildings, furniture, computers, and electronic systems. In Khartoum, account holders in all bank branches have been unable to access their accounts as all banks were closed. Though banks outside Khartoum have been operational, a lack of inter-branch linkages due to the centralization of banking operations in Khartoum and heavy dependence on headquarters, has posed a challenge. Bank of Khartoum, which has its own independent switch, succeeded in accessing its server, providing it with stable power supply and managed to intermittently restore its systems online, since the early days of the conflict, to provide digital services to its customers including billing payments, and Western Union cash remittances. Since July, many other banks have been able to restore their systems.

‘Recently, CBoS managed to restore its core banking system, connecting about 23 out of the 37 banks in Sudan, however, it has not managed to restore the electronic clearance system, and money transfer between banks is not yet possible. Mobile money transfers, mobile payments and electronic banking applications are functional but with frequent system disruptions due weaknesses in the communication networks, internet outages and frequent power cuts.[footnote 42]

8.1.5 The same source further noted that: ‘Sudan is primarily a cash-based society’ but ‘accessing cash has been difficult for the affected population since the conflict erupted.’[footnote 43] OCHA humanitarian update report 19 October 2023 noted: For instance, the disruption in the banking system continues to affect the ability of people, government institutions and humanitarian organizations to withdraw or transfer money, pay for services and procure supplies. Cash availability or access to cash has been a recurring issue raised by several partners as many are not able to get their project funds as the banking system is not fully functional.’[footnote 44]

8.1.6 As a result dependence on mobile money transfer services has increased since the conflict and informal money transfer and banking agents operators have emerged to help address the need for cash withdrawal but they charge a substantial fee ranging from 10–50 per cent of the transfer value, depending on the location and availability of cash[footnote 45].

8.1.7 In December 2023 Data Friendly Space (DFS), a U.S. based INGO working globally to make modern data systems and data science accessible to the humanitarian and development communities[footnote 46] and iMMAP, an international not-for-profit organization that provides information management services to humanitarian and development organizations,[footnote 47] published a report on the situation in Sudan between October and November 2023, based on secondary data review (DFS and iMMAP report December 2023). The report stated:

‘… Continued disruptions in the banking system impede individuals, government entities, and humanitarian bodies alike. This limitation severely impacts organizations’ capacity to access and transfer funds, resulting in challenges to make payments for essential services and procure necessary supplies. Limited access to cash remains a recurring problem for numerous aid organizations who are unable to access project funds due to the incomplete functionality of the banking system. As a result, organizations cannot reach people with humanitarian support and people in need struggle to access services like healthcare, food, clean water etc.’[footnote 48]

9. Security situation

9.1.1 For detailed information on the security situation in Sudan including fatalities and destruction of civilian infrastructure see Country policy and information note: security situation, Sudan, June 2023 However, there have been changes since the publication of this report.

9.1.2 A November 2023 report by the International Office for Migration Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM), which collects, analyses and disseminates information about displaced people,[footnote 49] (IOM report November 2023) noted that continued incidents of conflict occurred across multiple hotspots particularly in Darfur, Kordofan and Khartoum, several armed groups, such as the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and the Sudanese Liberation Movement (SLM Mini-Minawi) renounced their commitment to neutrality and more localized fighting has emerged in South Kordofan North Darfur, South Darfur, and Blue Nile.’[footnote 50]

9.1.3 According to a January 2024 situation report by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), which collects information on the dates, actors, locations, fatalities, and types of all reported political violence and protest events around the world[footnote 51] since fighting first broke out on 15 April, ACLED reports approximately 4,000 incidents of political violence and more than 13,000 fatalities. From 25 November to 5 January 2024, there were over 640 political violent incidents and 720 recorded deaths with the majority - over 440 incidents and 315 reported deaths occurring in Khartoum. Al-Jazirah state had the second largest number of political violence occurrences, with over 70 and more than 110 reported fatalities.[footnote 52]

9.1.4 The same source further noted:

‘After the conflict between the RSF and the SAF broke out in April 2023, Wad Madani emerged as a critical humanitarian hub, hosting hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people (IDP) escaping the conflict in Khartoum. It served as the initial destination for those leaving the capital before seeking refuge in other countries or Sudanese states, owing to its strategic location in the southeast of Khartoum …

‘On 15 December 2023, the RSF initiated a large-scale offensive against the SAF, with RSF forces advancing toward the outskirts of Wad Madani, where the clashes concentrated for three days in at least 17 distinct towns and villages …

‘On 18 December… the RSF gained control of Wad Madani and most other cities in al-Jazirah state…

‘During the attack in al-Jazirah, there were widespread atrocities committed by the RSF. RSF troops were accused of looting several civilian populated areas, while also killing and raping local residents and displaced citizens … After gaining control of Wad Madani and al-Haj Abdallah, the RSF restricted civilian movement by preventing them from fleeing to Sennar. This action further exacerbated the challenges of accessing humanitarian aid and the last few functioning health facilities by civilians attempting to escape the conflict zones, contributing to the overall humanitarian crisis in the region.’[footnote 53]

9.15 The same source further observed:

‘The capture of al-Jazirah by the RSF stands as a defining moment in the ongoing conflict with the SAF. This event has not only led to an expansion of hostilities into new territories, particularly in the middle regions such as Sennar state, but it has also brought forth threats of RSF attacks on River Nile, Gedaref and Port Sudan. Simultaneously, the fall of Wad Madani city has triggered ethnic mobilization across areas under SAF control, casting doubt on the SAF’s ability to protect these regions. Furthermore, this situation has the potential to prompt defections within the SAF ranks in response to their withdrawal from Wad Madani, with many Sudanese calling the SAF chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to step down.’[footnote 54]

9.1.6 According to the International Crisis Group January 2024 Crisis Watch report the RSF advanced south into Sennar, White and Blue Nile states and after capturing Wad Medani the army began to arm civilians in Al Jazirah and the RSF threatened to continue offensives into eastern Gedarif, Kassala and Port Sudan if civilian recruitment continued. The source further reported the formation of new militias that support army and the RSF -SAF fighting has turned into ethnic-based conflict between non-Arab Nubian SPLM-N (al-Hilu) and RSF-affiliated Misseriya and Hawazma Arab militias.[footnote 55]

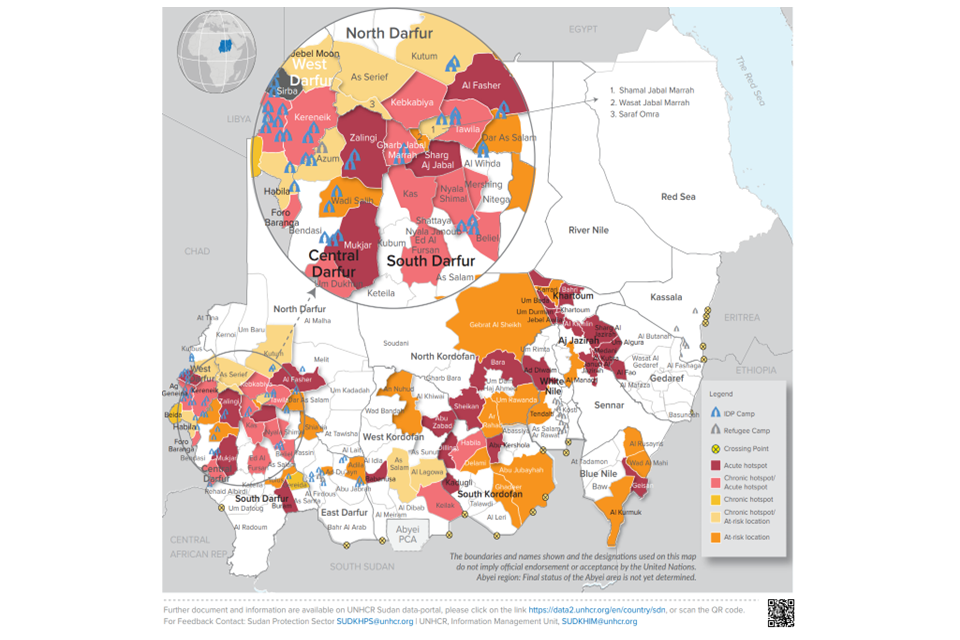

9.1.7 According to the Global Protection Cluster, a network of NGOs, international organisations and UN agencies engaged in protection work in humanitarian crises including armed conflict[footnote 56] as of 31 December 2023 there were 202 hotspot sites, 72 hotspot localities and 13 hotspot states in Sudan.[footnote 57] CPIT has produced below chart based on the Global Protection Data showing the number of hotspot sites and localities in each of the 13 states. For information on the names of hotspot localities see Global Protection Cluster, ‘Protection Hotspots in Sudan’, as of 31 December 2023

9.1.8 ‘The Protection Sector hotspot mapping distinguishes between (1) chronic conflict hotspots – areas that are affected by prolonged, protracted and/or repeated inter-communal violence, armed attacks and low intensity conflict (2) acute conflict hotspots – areas that are currently affected by new violence, armed attacks or active armed conflict and (3) at-risk locations – location that are at risk of inter-communal violence or armed conflict in the near future, and/or where civilians are at risk of attacks.’[footnote 58]

Protection hotspot in Sudan as of 31 December 2023:

| Area | Hotspot sites | Localities |

|---|---|---|

| South Darfur | 48 | 10 |

| North Darfur | 38 | 7 |

| West Kordofan | 22 | 6 |

| Central Darfur | 18 | 8 |

| South Kordofan | 18 | 7 |

| West Darfur | 18 | 7 |

| Blue Nile | 15 | 4 |

| Al Jazirah | 6 | 6 |

| Khartoum | 6 | 6 |

| North Kordofan | 5 | 5 |

| East Darfur | 5 | 3 |

| White Nile | 2 | 2 |

| Gedaref | 1 | 1 |

9.1.1 The Global Protection Cluster has provided the below map of Sudan showing protection hotspots.”[footnote 59]

10. People in need

10.1 Nationality

10.1.1 The OCHA HRP May 2023 noted: ‘The situation in Sudan has significantly worsened since the last update on humanitarian needs was released in November 2022 … The number of people in need (PiN) of humanitarian assistance has increased from 15.8 million, estimated in November 2022, to 24.7 million in May 2023, representing a 57 per cent increase.’[footnote 60] The figures of the PiN comprised of 15.1 million vulnerable residents, 7.2 million IDPs, 1.1 million refugees and 1.3 million returnees.[footnote 61]

10.1.2 With respect to children, a November 2023 report by UNICEF, stated that 13.6 million children were in need of humanitarian assistance and 3 million children were internally displaced as at 31 October 2023.[footnote 62]

10.1.3 The OCHA HRP report May 2023 noted that majority of PiN were in Khartoum (12.1%), followed by North Darfur (11.0%), South Darfur (9.4%), Al Jazirah (8.1%), White Nile (7.7%), West Darfur (6.1%) Kassala (5.7%), Central Darfur (5.3%), Gedaref (4.9%), South Kordofan 4.5%) and North Kordofan (4.1%).[footnote 63]

10.1.4 CPIT has produced the table below showing the population and the PiN in each state in 2023 based on OCHA data.[footnote 64]

| State | Population excluding refugees | PiN - excluding refugees | Population (including refugees) | PiN including refugees | PiN as % of population (including refugees ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abyei PCA | 250,000 | 200,750 | 250,000 | 200,750 | 80% |

| Al Jazirah | 5,687,557 | 1,997,778 | 5,705,029 | 2,018,214 | 35% |

| Blue Nile | 1,344,267 | 717,211 | 1,357,645 | 731,596 | 54% |

| Central Darfur | 1,786,503 | 1,266,024 | 1,797,765 | 1,278,396 | 71% |

| East Darfur | 1,213,951 | 731,299 | 1,313,743 | 826,723 | 63% |

| Gedaref | 2,545,604 | 1,153,661 | 2,613,485 | 1,233,863 | 47% |

| Kassala | 2,811,446 | 1,315,003 | 2,922,045 | 1,414,924 | 48% |

| Khartoum | 9,146,191 | 2,807,836 | 9,452,977 | 2,995,252 | 32% |

| North Darfur | 2,775,652 | 2,623,040 | 2,806,903 | 2,652,917 | 95% |

| North Kordofan | 2,160,476 | 1,029,655 | 2,170,273 | 1,039,022 | 48% |

| Northern | 1,023,194 | 380,277 | 1,024,332 | 381,369 | 37% |

| Red Sea | 1,549,857 | 827,584 | 1,556,251 | 850,520 | 55% |

| River Nile | 1,651,873 | 632,011 | 1,655,605 | 635,583 | 38% |

| Sennar | 2,170,863 | 850,150 | 2,180,763 | 859,793 | 39% |

| South Darfur | 3,912,372 | 2,290,711 | 3,963,470 | 2,343,267 | 59% |

| South Kordofan | 2,017,962 | 1,065,859 | 2,061,243 | 1,107,238 | 54% |

| West Darfur | 1,940,860 | 1,539,659 | 1,941,286 | 1,540,072 | 79% |

| West Kordofan | 1,713,462 | 677,768 | 1,786,309 | 747,712 | 42% |

| White Nile | 3,046,811 | 1,566,016 | 3,328,773 | 1,910,584 | 57% |

| Total | 48,748,901 | 23,586,478 | 49,887,897 | 24,681,639 | 49% |

11. Displaced population

11.1 Total displacement

11.1.1 The IOM ‘Monthly Displacement Overview’ February 2024 (IOM Overview report February 2024 noted:

‘…In late December 2023, Sudan DTM analysed extensive displacement data to produce an updated, comprehensive estimate of persons displaced within Sudan, accounting for both those displaced before and after 15 April 2023. DTM Sudan reported that approximately 9,052,822 persons were internally displaced in Sudan, while an estimated 1,574,135 individuals were displaced across Sudan’s borders into neighbouring countries. Additionally, 120,797 IDPs were foreign nationals (approximately 2 per cent of total IDPs across Sudan).’[footnote 65]

11.1.2 The OCHA SSR 4 February 2024 noted:

‘Of the 10.7 million people displaced, 1.7 million have fled to neighbouring countries, the vast majority (62 per cent) being Sudanese. Chad hosts the majority of arrivals at 37 per cent, with South Sudan at 30 per cent, Egypt at 24 per cent while Ethiopia, Libya and the Central African Republic host the remainder. This creates additional humanitarian needs in a region that is already in deep crisis. Their needs are overwhelming: shortages of food, shelter, healthcare, and sanitation, all combine to place them at heightened risk of disease, malnutrition, and violence, according to the IOM. that about 10.7 million people are now displaced by conflicts in Sudan of which 9 million are displaced inside the country.’[footnote 66]

11.1.3 IOM Overview report February 2024 has provided below figure showing monthly displacement between 21 April and 31 December 2023:

11.2 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

11.2.1 The IOM report January 2024 noted:

‘Since 15 April 2023, DTM Sudan estimated that 6,036,176 individuals (1,201,356 Households) were displaced across 6,512 locations, within 180 localities, across all 18 states in Sudan. Recent clashes resulted in an unprecedented rate of displacement in Sudan—with an average increase of approximately 200,000 IDPs every week. The number of displacements that occurred in 2023 (6,036,176) was over 5 times greater than the number of displacements estimated to have occurred in 2022 (235,963). The number of individuals displaced was higher, and the frequency of population displacement was more frequent, during the 8.5 months since 15 April 2023 as compared to the cumulative 20 years prior.’ [footnote 67]

11.2.2 With respect to the origins of IDP, the same source stated:

‘As the epicenter of conflict, Khartoum experienced the greatest displacement nation-wide, with an estimated 3,681,297 individuals displaced from Khartoum state since 15 April 2023. Following Khartoum, and with the exception of East Darfur, residents originating from the Darfur states experienced the highest numbers of population displacement represented by the following estimates: South Darfur (1,867,019 individuals), North Darfur (1,085,684 individuals), Central Darfur (665,483 individuals) and West Darfur (353,689 individuals). Over 509,796 individuals in Aj Jazirah state were displaced, (approximately 275,796 IDPs were primarily displaced and approximately 234,000 IDPs were secondarily displaced) over the course of three days in December 2023. As such, Aj Jazirah is the area of origin for the sixth largest proportion of IDPs (335,959 individuals).’ [footnote 68]

11.2.3 CPIT has produced below table based on IOM[footnote 69] data and OCHA data[footnote 70] showing IDPs states of origin and proportion of IDP to state population and total IDP population.

| State | Total Population | IDPs originating | As % of state population | IDPs as % of total IDPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Jazirah | 5,705,029 | 470,212 | 8.2% | 7.7% |

| Central Darfur | 1,797,765 | 249,562 | 13.9% | 4.1% |

| East Darfur | 1,313,743 | 75,535 | 5.7% | 1.2% |

| Khartoum | 9,452,977 | 3,525,379 | 37.3% | 57.8% |

| North Darfur | 2,806,903 | 498,143 | 17.7% | 8.2% |

| North Kordofan | 2,170,273 | 42,690 | 2.0% | 0.7% |

| Sennar | 2,180,763 | 15,592 | 0.7% | 0.3% |

| South Darfur | 3,963,470 | 936,434 | 23.6% | 15.4% |

| South Kordofan | 2,061,243 | 63,135 | 3.1% | 1.0% |

| West Darfur | 1,941,286 | 188,497 | 9.7% | 3.1% |

| West Kordofan | 1,786,309 | 21,819 | 1.2% | 0.4% |

| White Nile | 3,328,773 | 8,090 | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| Total | 38,508,534 | 6,095,088 | 100.0% |

11.2.4 1. Regarding the states where the IDPs have relocated, the same source stated:

‘… The states hosting the highest numbers of IDPs are South Darfur (18% of total displaced, as of 31 December 2023), North Darfur (13% of the total displaced population), Central Darfur (9% of the total displaced population) and East Darfur (9% of the total displaced population). North Darfur and South Darfur are where the most IDPs originated and where most are hosted, indicating that the majority of displaced households sheltered in their state of origin. Given the sustained pace of armed clashes, it is likely that the short distance travelled by IDPs reflects their financial or physical inability to travel rather than their optimism that they will soon return to their area of origin.’ [footnote 71]

11.2.5 IOM Overview report February 2024 as provided the below table showing displacement by state since April 2023.[footnote 72]

| State of displacement | Localities | Locations | IDPs | IDPs % (grand total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Jazirah | 8 | 1,492 | 389,881 | 6% |

| Blue Nile | 7 | 126 | 131,474 | 2% |

| Central Darfur | 8 | 21 | 373,935 | 6% |

| East Darfur | 9 | 28 | 660,830 | 11% |

| Gedaref | 12 | 252 | 377,643 | 6% |

| Kassala | 10 | 187 | 166,228 | 3% |

| Khartoum | 7 | 204 | 44,769 | 1% |

| North Darfur | 17 | 114 | 460,188 | 8% |

| North Kordofan | 8 | 537 | 147,095 | 2% |

| Northern | 7 | 327 | 402,675 | 7% |

| Red Sea | 8 | 176 | 239,027 | 4% |

| River Nile | 7 | 878 | 700,827 | 12% |

| Sennar | 7 | 369 | 434,627 | 7% |

| South Darfur | 18 | 47 | 703,118 | 12% |

| South Kordofan | 14 | 357 | 127,637 | 2% |

| West Darfur | 7 | 43 | 128,540 | 2% |

| West Kordofan | 14 | 509 | 101,030 | 2% |

| White Nile | 9 | 880 | 503,264 | 8% |

| Grand total | 117 | 6,547 | 6,092,788 | 100% |

11.2.6 With respect to IDP shelter, the IOM January 2024 report observed:

‘IDPs’ shelter typologies also reflect a dire financial and humanitarian situation. An alarming 19 per cent, or 334,594 households, were estimated to shelter in abandoned buildings, gathering sites, schools or other public buildings. Most IDP households in Sudan sheltered within the host community (49%, or 884,926 households). IDPs’ choice to reside with the host community may reflect their support from tribal connections and sheltering where a known social network exists. However, sheltering with communities increases demands on resources and may spur social tensions. Around a quarter of IDP households (27%, or 483,474 households) were sheltering in IDP camps. Individuals more commonly sheltered in the host community, camps, gathering sites (154,189) and schools or other public buildings (158,658), before rented accommodation (103,609).’[footnote 73]

11.2.7 With respect to gender and age distribution of the IDPs, the same source noted:

‘‘In every age bracket analysed by DTM Sudan, female IDPs outnumbered male IDPs. Most IDPs were between 18 and 59 years old (3,602,156), of whom 1,875,529 (52%) were women. The next most populous age range of IDPs was between 6 and 17 years old (2,716,145), of whom, 53 per cent were females and 47 per cent were males. Notably, an estimated 24 per cent of all IDPs were children between the ages of 0 and 5 years old …’ [footnote 74]

11.3 Status and treatment of displaced populations

11.3.1 OCHA humanitarian update 7 December 2023 noted:

‘Since April 2023, UNHCR and its partners reached over 455,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) with protection, relief supplies, shelter and cash assistance in a challenging and complex operational environment. In 2023, UNHCR supported nearly 85,000 of the most vulnerable IDPs and members of the host community with cash support of some US$3.2 million. UNHCR implements multi-purpose cash assistance for protection and basic needs along with cash for shelter programmes benefitting displaced people and host communities living together. In addition, UNHCR, together with its partners, is piloting cash for economic empowerment initiatives. This three-tiered cash approach aims to improve social protection and to catalyse community-driven economic recovery. Prior to the conflict, UNHCR’s cash interventions were centred on Darfur, while after its start, UNHCR’s cash interventions also reached people in the east and the north of the country.’[footnote 75]

11.3.2 IOM report November 2023 has provided below figure showing the IDPs access of various services.[footnote 76]

Access to services (proportion of IDPs) provided in the state:

| Not available at all | Available but not affordable | Available to access with no complication | Available but not good quality | Available but not safe to access | Available but too far from location | Available but overcrowded | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | - | 53% | 21 | 20% | 2% | 3% | 1% |

| Market Food | - | 95% | - | 2% | 1% | 2% | - |

| Market NFI | 1% | 73% | 7% | 1% | 13% | 5% | |

| Healthcare | 24% | 31% | 2% | 39% | 2 | 2% | - |

| Education | 75% | 4% | 3% | 7% | - | - | 10 |

| Transport/ Fuel | 10% | 61% | 10% | 12% | - | 7% | - |

| Electricity | 48% | 7% | 7% | 37% | - | - | - |

| Government services | 56% | 20% | 3% | 6% | - | 14% | - |

11.3.3 IDPs access to services differed from state to state. For information on each state see IOM DTM Overview report February 2024.

‘Sanitation is particularly poor in IDP sites, since available facilities are under pressure because of the large influx of IDPs. In White Nile, the few available sanitation points are insufficient to serve the influx of displaced people. As at 2 August 2023, water demand in IDP sites in White Nile state had risen from 15m3 before the conflict to more than 300m3 per day.

‘The available sewer installation in White Nile IDP sites had also been exceeded, developing a risk of transferring waterborne diseases.‘[footnote 77]

12. Food security

12.1 Overview

12.1.1 The WFP noted in its Sudan webpage noted:

‘The humanitarian situation in Sudan is teetering on the brink of catastrophe after conflict erupted across the country in mid-April 2023. Since 2019, the number of people facing acute food insecurity has more than tripled from 5.8 million to nearly 18 million. Nearly 5 million of these are in emergency levels of hunger.

‘The key drivers of the worsening food security situation include intensified conflict and growing intercommunal violence, economic crisis, soaring prices of food, fuel and essential goods, and below average agricultural production.’[footnote 78]

12.1.2 The December 2023 report by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), an innovative multi-partner initiative for improving food security and nutrition analysis and decision-making,[footnote 79] noted:

‘The latest projection update of Sudan reveals that intense conflict and organized violence, coupled with the continued economic decline, have driven approximately 17.7 million people across Sudan (37 percent of the analysed population) into high levels of acute food insecurity, classified in IPC Phase 3 or above (Crisis or worse) between October 2023 and February 2024. Of those, about 4.9 million (10 percent of the population analysed) are in IPC Phase 4 (Emergency), and almost 12.8 million people (27 percent of the population analysed) are in IPC Phase 3 (Crisis).

‘… The most acutely food insecure populations are in states affected by high levels of organized violence, including Greater Darfur, Greater Kordofan and Khartoum – especially the tri-city area of Khartoum, Bahri and Omdurman. Across all areas heavily affected by conflict and organized violence, civilians experiencing movement restrictions, including due to sieges, are at heightened risk of high levels of food insecurity.’[footnote 80]

12.1. 3 Citing various sources, the DFS and iMMAP report December 2023 noted:

‘… In Khartoum state, 3.9 million people (55 percent of the population) face high level of food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or above), while in Greater Darfur about 5.3 million people (that represent 46 percent of the total population in Darfur region) are likely to be in Phase 3 or above. In Greater Kordofan, about 2.7 million (44 percent of the total population in Kordofan states) are in Phase 3 or above. These are the highest ever recorded figures during the harvesting season in Sudan.

‘… [T]he concentration of highest levels of severity and prevalence of food insecurity [are] in areas where the conflict is more intense. West Darfur (22%), Central Darfur (17%) Khartoum (17%), and West (16%) and South Kordofan (15%) are the states projecting the largest proportion of population experiencing IPC 4 by February 2024.’[footnote 81]

12.1.4 According to a November 2023 WFP report that analysed the relationship between conflict and the rising food prices in Sudan (WFP report November 2023):

‘The greater Darfur, the Kordofans and Khartoum States account for approximately 40 and over 80 percent of the total national production of sorghum and millet [the most consumed stapple foods], respectively. Agricultural activities in these States have been hampered by episodes of active conflict leading to reduced planting which is likely to result in reduced harvests. The fallout of the conflict has been observed in other neighbouring States where sorghum is produced [Gedarif, El Gazira, Blue Nile, Sennar, White Nile], which may contribute to deficits in cereal crop production both regionally and nationally. Shortages in local markets and price spikes in the near-to-medium term are likely to occur, leading to a further erosion of the already compromised household purchasing power.’[footnote 82]

12.1.5 The OCHA SSR February 2024 noted:

‘About 16 million people in Sudan have insufficient food consumption, according to the World Food Programme (WFP)’s Hunger Map. Darfur has the highest ratio of people with insufficient food consumption; in four of five states, it is more than 40 per cent of their respective state populations. West Darfur has about 49 per cent of its people with insufficient food consumption, in Central Darfur it is 46 per cent, in North Darfur 42 per cent, in South Darfur 41 per cent, and in East Darfur 33 per cent. According to the latest Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) report on Sudan, 17.7 million people are acutely food insecure across Sudan between October 2023 and February 2024, including 4.9 million who are in emergency levels of acute food insecurity.’[footnote 83]

12.1.6 The OCHA Humanitarian Dashboard of 31 December 2023 (OCHA HD 31 December 2023) noted: ‘Vulnerable groups, including women, children, persons with disabilities, refugees, and internally displaced persons, continue to face severe food insecurity conditions.’ [footnote 84]

12.1.7 For details on food situation in all states, see WFP Sudan Hunger Map.

12.2 Food prices

12.2.1 A September 2023 report by FEWS NET observed:

‘Staple foods prices indicated mixed trends across main markets in Sudan during the third week of September, the peak lean season, due to the continued disruption to flows and supplies. Price increases of 10-20 percent were seen in the main markets across Greater Darfur and Greater Kordofan, as well as in Dongola market in Northern state, as a result of tightened market supplies and increased marketing and transportation costs. By contrast, sorghum and millet prices in the markets of Ed Damazin, Sennar, and Gedaref … showed an unseasonal decline of around 10 percent driven by the continued disruptions to trade flow along key corridors, particularly from east to west, and in market functionality in conflict-affected areas. On average, the retail price of sorghum in September was 6 percent higher than in September 2022, while millet price is 16 percent lower compared to September 2022 prices… Locally produced wheat prices recorded the highest price increase of 29 percent compared to September 2022 … Overall, cereal prices remain significantly above their five-year average – 252, 259, and 175 percent higher for sorghum, wheat, and millet, respectively – driven by high production and transportation costs, high inflation, and persistent local currency depreciation …’[footnote 85]

12.2.1 WFP has produced below table showing staple price changes in key markets: [footnote 86]

| State | Market | Commodity | September 2023 | Year on year | % change from March |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Darfur | Al Fashir | Sorghum | 1,988 | 42% | 43% |

| North Darfur | Al Fashir | Millet | 2,200 | -8% | 34% |

| Blue Nile | Damazin | Sorghum | 1,225 | -35% | -18% |

| Blue Nile | Damazin | Millet | 2,125 | -15% | 6% |

| West Kordofan | El Fula | Sorghum | 1,467 | -8% | 60% |

| West Kordofan | El Fula | Millet | 2,367 | -7% | 122% |

| North Kordofan | El Obeid | Sorghum | 1,267 | -10% | 32% |

| North Kordofan | El Obeid | Millet | 2,000 | -17% | 45% |

| South Kordofan | Kadugli | Sorghum | 1,817 | 40% | 82% |

| South Kordofan | Kadugli | Millet | 2,200 | 10% | 10% |

| Kassala | Kassala | Sorghum | 925 | -20% | 16% |

| Kassala | Kassala | Millet | 1,750 | -30% | 40% |

| White Nile | Kosti | Sorghum | 1,000 | -18% | 25% |

| White Nile | Kosti | Millet | 1,850 | -31% | 23% |

| Red Sea | Port Sudan | Sorghum | 840 | -15% | -11% |

| Red Sea | Port Sudan | Millet | 1,380 | -32% | -1% |

12.2.3 A December 2023 report by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) commented that ‘Surging market prices due to diminished access to agricultural livelihoods and transportation routes, insecurity, and shortages of basic goods continue to threaten food security countrywide, according to the UN World Food Program (WFP).’[footnote 87]

12.3 Provision of food assistance

12.3. 1 In its Sudan webpage, no date, WFP noted: ‘Despite widespread insecurity and access constraints, WFP has delivered life-saving food and nutrition assistance to over 5.2 million people since the start of the conflict – including in some of the most hard-to-reach areas in the Darfur region.’[footnote 88]

12.3. 2 The OCHA HD 31 December 2023) noted:

‘Between 1 January and 31 December the FSL Cluster has reached 10.86M people across Sudan with life-saving food and emergency livelihoods assistance with the support of 39 FSL Partners. Around 157 localities were covered with FSL response in 18 states with 4.68M beneficiaries with Food assistance and 6.2M with emergency livelihoods response.

‘Between 15th April and 31st December the FSL sector has reached 9.49M people with life-saving food and emergency livelihoods assistance during the reporting period. The FSL response covered 154 localities in 18 states with 3.76M beneficiaries provided with food and 5.72M beneficiaries provided with emergency livelihoods assistance.

‘Whilst the FSL Cluster was able to reach 10.86M people since the beginning of 2023, it is only 72.4% of the overall target. The FSL sector was unable to reach the remaining 28.6% due to security reasons, access constraints, and other limitations caused by the escalation of the conflict in Sudan.’[footnote 89]

12.3.3 The same source noted that 42 organisations worked in the FSL cluster and that of the US$581.2 million required for FSL cluster US$ 293.4 million (50.5%%) had been received.[footnote 90]

13. Education

13.1 Impact of fighting on education

13.1.1 The OCHA HRP 17 May 2023 observed with respect to the impact of the conflict on education:

‘Education has been severely affected, with schools and educational institutions remaining closed in conflict-affected areas, namely Khartoum, Aj Jazirah, South Darfur, West Darfur and West Kordofan. With approximately 6.9 million children not attending school before the conflict, the learning crisis has deepened with higher levels of risk of physical and mental threats, including recruitment into armed groups. As of 11 May, schools and educational institutions have started to reopen in areas not affected by hostilities, preparing for the final academic year examinations.’[footnote 91]

13.1.2 The same source added:

‘The conflict has negatively impacted the education of affected girls, boys and adolescents, including children with disabilities who face challenges in accessing inclusive quality education in a safe and protective learning environment. In addition, the conflict exposes vulnerable children to a range of life-threatening risks such as GBV including child marriage; female genital mutilation (FGM); human / sex trafficking and SEA recruitment by armed actors and child labour. Structured learning programmes protect children from exploitation, abuse, and involuntary recruitment into armed groups.’[footnote 92]

13.1.3 A 15 November 2023 report by OCHA observed:

‘The conflict has deprived about 12 million children of schooling since April, with the total number of children in Sudan who are out of school reaching 19 million, Save the Children (SC) and the UN Children’s Agency (UNICEF) reported. Of this total, 6.5 million children — or 1 in every 3 children in the country — have lost access to school due to increased violence and insecurity, with at least 10,400 schools now closed in conflict - affected areas. Meanwhile, over 5.5 million children who reside in areas less affected by war are waiting for local authorities to confirm whether classrooms can be re-opened. Before April, nearly 7 million children were already out of school. If the war continues, no child in Sudan can return to school in the coming months, exposing them to immediate and long-term dangers, including displacement, recruitment into armed groups and sexual violence. Sudan is on the brink of becoming home to the worst education crisis in the world,” according to UNICEF.’[footnote 93]

13.1.4 OCHA HRD 18 December 2023 noted:

‘More than half of children enrolled in schools in the conflict-affected states, approximately 6.4 million children, had their learning disrupted and suspended till the end of Oct 2023. In addition, 2 million school-aged children have been internally displaced and have no access to education services. Schools have been destroyed with some occupied by armed groups and IDPs. These schools remain far from safe and protective spaces. Despite the school re-opening plans in place, only River Nile has re-opened schools in a phased manner and there are on-going school re-opening discussions in the rest of the states.’[footnote 94]

13.2 Assistance in education

13.2.1 OCHA HRD 31 December 2023 noted that of the US$131.0 million funding required for the education cluster to assist 4.3 million people out of the 8.6 million people in need, US$15.5M (11.9%) had been received as at 31 December 2023.[footnote 95] The same source noted that 16 organisations provided educational assistance.[footnote 96]

13.2.2 A November 2023 report by UNICEF stated:

‘… UNICEF and partners established 751 child friendly safe learning spaces since January 2023 to provide close to 187,000 children, including over 94,000 girls, structured learning and an opportunity to resume friendships, socialize with their peers, engage in playful learning, develop skills, receive care and basic psychosocial support towards their holistic development by trained and attentive teachers.

‘During the reporting period, UNICEF established 77 new safe learning spaces, including in safe pockets in hotspot states like East Darfur, West Darfur, and the Kordofans and welcomed around 13,900 additional children. Of these, almost 5,700 girls and boys received learning materials and 4,108 adolescents actively engaged in adolescent-led sports, cultural, and health clubs to further enhance their overall wellbeing and holistic development. Moreover, 1,118 facilitators have been trained and equipped with skills to support children’s wellbeing and learning.

‘UNICEF’s Learning Passport continues to support uninterrupted learning for affected children, including those in areas of active conflict, displaced or on the move. Currently, over 33,000 children (with more than 7,300 users in October alone) both in Sudan and in neighbouring countries have been reached with access to quality, inclusive and gamified education through the programme.’ [footnote 97]

13.2.3 OCHA HRD 31 December 2023 noted:

‘The Education emergency response has provided education opportunities to 87,433 (44,419 girls) crisis-affected children. Safe learning centres have been established to ensure children’s safety. The children have been supported with psychosocial services, learning materials and recreational materials.

‘Furthermore, the Education Sector has been pushing its advocacy for school re-opening with the State ministry of Education.

Education gaps remain huge with only 87,433 of the 4.3 million targeted children reached. 2 million school aged children have been internally displaced and an estimated 5 million children are still trapped in conflict hotspots.

There are two main challenges to re-opening schools - lack of finances to support the teacher’s salary and the fact that 8% of schools are used as shelter by displaced people.’[footnote 98]

The Education emergency response has provided education opportunities to 87,433 (44,419 girls) crisis-affected children Safe learning centres have been established to ensure children’s safety. The children have been supported with psychosocial services, learning materials and recreational materials.

‘Education gaps remain huge with only 87,433 [or 2 %] of the 4.3 million targeted children reached. 2 million school aged children have been internally displaced and an estimated 5 million children are still trapped in conflict hotspots.

‘There are two main challenges to re-opening schools - lack of finances to support the teacher’s salary and the fact that 8% of schools are used as shelter by displaced people.’[footnote 99]

14. Healthcare

14.1 Access to health care before the conflict

14.1.1 CI report May 2023 observed: ‘Before the conflict broke out in 2023, 70% of the population reported that they had access to a health facility within 30 minutes travel from their home and 80% has access to health facilities within one-hour’s travel; however, these facilities were poorly equipped (including limited electricity) and had minimal staff with the appropriate range of skills to meet the needs of the community…’[footnote 100]

14.1.2 Acaps report 21 June 2023 noted:

‘Before the April conflict, access to healthcare was already severely constrained throughout Sudan, which faced a shortage of facilities, personnel, medicine, and equipment.

‘… Sudan was unable to maintain a steady supply of medicine and medical resources because of poor macroeconomic conditions and a lack of hard currency. A 2022 survey found that an average of 31%, 30%, and 51% of critical medication was respectively available in public, private, and humanitarian-supported health facilities. Aid and medical supplies were mostly dispatched from Khartoum, and laboratory tests and other aspects of health provision were performed in the capital, where there was a highly centralised health system. During the 2022 flooding, the affected population lacked access to basic medicine and first aid kits … Insecurity is expected to continue disrupting this supply chain in Khartoum, with several health facilities, labs and warehouses being occupied, affecting conflict-affected and flood-prone states. Furthermore, humanitarian-run facilities require permission from SAF to resupply, which is being frequently blocked in RSF-controlled areas.’[footnote 101]

14.2 Access to health care before the conflict

14.2.1 A September 2023 article ‘by Alaa Dafallah and others published by Conflict and Health, a peer reviewed open access journal documenting the public 1. health impacts and responses related to armed conflict, humanitarian crises and forced migration[footnote 102] stated:

‘Healthcare services have been severely compromised. As of 23rd July, less than one third of hospitals in conflict zones are functional, with 70% of hospitals out of service. Of the 59 hospitals out of service in conflict zones, 17 were attacked by artillery and 20 were evacuated, of which 12 have been forcibly militarized and converted into barracks by the RSF. The remaining hospitals suspended services due to power outages, shortage of fuel for generators, lack of medical supplies and critical lack of health workers. Additionally, the RSF also seized multiple public health assets critical for service delivery including the National Public Health Laboratory, the Central Blood Bank, and the National Medical Supplies Fund, contributing to critically low medical supplies and blood reserves across several other states …

‘In-service hospitals are reporting severe health worker shortages. Health workers are among thousands that have fed the capital since the start of the war severely limiting capacity in hospitals. The remaining health workers are either unable to access health facilities due to fear for their safety or are exhausted, burdened by acute shortages in specialized cadres such as surgeons and anaesthetists and medical supplies.

‘Violence against health workers, albeit not new to Sudan, has escalated. Since the commencement of the conflict, 13 health workers were killed, 4 have been abducted by militia and 9 are reported missing.’[footnote 103]

14.2.2 The WHO’s September 2023 situation report noted:

‘More than 70% of health facilities in conflict-affected states areas are non-functional, leading to extremely limited – and sometimes no – access to health care for millions in Sudan, who are either trapped in war zones or displaced.

‘Shortages of medicines and medical supplies, including treatment for chronic diseases continue to be reported despite provision of supplies by health partners, including WHO. Health care workers have not been paid for four months, triggering strikes in some states like Red Sea, Northern and Kordofan.

‘Insecurity, displacement, limited access to medicines, medical supplies, electricity and water continue to pose enormous challenges to the delivery of health care across the entire country. Both states directly affected by the conflict such as Khartoum, West, Central and South Darfur, and North and South Kordofan and relatively peaceful states feel the brunt of the war and its effect on health care. States not directly affected by the war are receiving displaced people, hence the strain on health care and other services.

‘… Closure of the Khartoum-Kadugli and Dilling-Kadugli roads is affecting the dispatch of medical supplies to several states in the western part of the country.’[footnote 104]

14.2.3 The October 2023 OCHA humanitarian access situation report noted ‘About 70 to 80 percent of hospitals in conflict-affected states are non-functional because of ongoing attacks combined with insecurity, shortages of medical supplies, and lack of cash to meet operational costs and salaries. For example, only 77 out of the 107 government-run dialysis centres are currently functional and those in place are severely limited in capacity, affecting more than 9,000 patients.’[footnote 105]

14.2.4 The OCHA HRD noted that as of 31 December 2023: ‘The health system and infrastructure in Sudan was already inadequate before the conflict With combat largely centered around urban centers, 70% of health facilities have become nonfunctional in conflict affected areas while remaining areas have significant shortages of staff, equipment, and medical supplies. Healthcare worker salaries have also been unpaid since the conflict began.’[footnote 106]

14.3 Attacks on health facilities

14.3.1 According to WHO Surveillance System for Attacks on Health Care (SSA), which displays data from countries with complex humanitarian emergencies, from 15 April to 14 December 2023, there had been 60 verified attacks on health facilities which caused 34 deaths and 30 injuries compared to 23 attacks, 7 deaths and 4 injuries in the whole of 2022. The report further noted that of the 60 verified attacks [from 15 April – 14 December 2023] 39 attacks impacted facilities, 8 transport, 23 personnel, 7 patients, 17 supplies, 7 warehouses.[footnote 107]

14.3.2 CPIT has produced below figure based on WHO SSA data showing numbers of monthly attacks and casualties from 15 April to 14 December 2023.[footnote 108]

Number of attacks and casualties 15 April to 14 December 2023:

| Month | Attacks | Deaths | Injuries |

|---|---|---|---|

| April | 27 | 8 | 18 |

| May | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| June | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| July | 3 | 1 | 17 |

| August | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| October | 4 | 23 | 0 |

14.4 Disease outbreak

14.4.1 The UN Security Council report on the situation in the Sudan and the activities of the United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in the Sudan (UNITAMS) of November 2023 noted with respect to health:

‘…More than 70 per cent of hospitals in the conflict-afflicted states are no longer functional. Disease outbreaks – including cholera, dengue fever, malaria and measles – that were under control before the conflict have been on the rise owing to the disruption of public health services and causing deaths. WHO launched a funding appeal to raise $145.2 million to provide medical support to 7.6 million people in dire need of health assistance.’[footnote 109]

14.4.2 UNICEF report November 2023 noted: