Tackling abuse and mismanagement 2015 to 16: full report

Published 20 December 2016

Applies to England and Wales

1. Introduction

1.1 Foreword from William Shawcross

Charities play a vital role in our society. When they are well run, with strong governance and leadership, they can have great impact and do a lot to support their beneficiaries.

By contrast, in the past year we have seen that when charities lack those qualities, there can be serious repercussions. A number of high profile cases have hit the headlines and public trust during this period. In our casework, we have identified particular themes and problems, but it is poor governance that runs through the heart of them. The lessons from this report must be learnt.

William Shawcross, Chairman, Charity Commission

1.2 About the Charity Commission

The commission is the independent regulator and registrar of charities in England and Wales. We are responsible for deciding if organisations are charitable and should be added to or removed from the register of charities, and we maintain that register to ensure its accuracy. Through our regulatory work we protect the public’s interest in charities and ensure that charities further their charitable purposes for the public benefit.

Our 5 statutory objectives are to:

- increase public trust and confidence in charities

- promote awareness and understanding of the operation of the public benefit requirement

- promote compliance by charity trustees with their legal obligations in exercising control

- promote the effective use of charitable resources

- enhance the accountability of charities to donors, beneficiaries and the general public

An important part of our role is to help prevent serious problems arising in the first place, by providing guidance that helps trustees understand and meet their legal duties and responsibilities in managing their charities. We also give charities permission or consent to enable the effective use of charitable resources by changing their objects and allowing them to operate more effectively. By volume, this remains the largest part of our work.

Our strategic plan for 2015 to 18 explains how we are fulfilling our objectives and the Annual report 2015 to 16 reports on our progress.

1.3 How we are continuing to focus on tackling abuse and mismanagement

We have continued to strengthen our work to prevent and stop abuse and mismanagement in charities this year, both in terms of the regulatory action we have taken and in our work with charities to be more proactive and take preventative measures. We are making more use of data to prevent and detect abuse and, alongside the Risk framework, this will help us focus our resources on the cases that need it most. Trustees can read about much of this in our Annual report 2015 to 16.

Our general approach to dealing with concerns about charities, including the powers available to us, is explained in Annex 1: the commission’s approach to tackling abuse and mismanagement. Trustees can read about the different kinds of cases we conduct into charities in Annex 2: glossary.

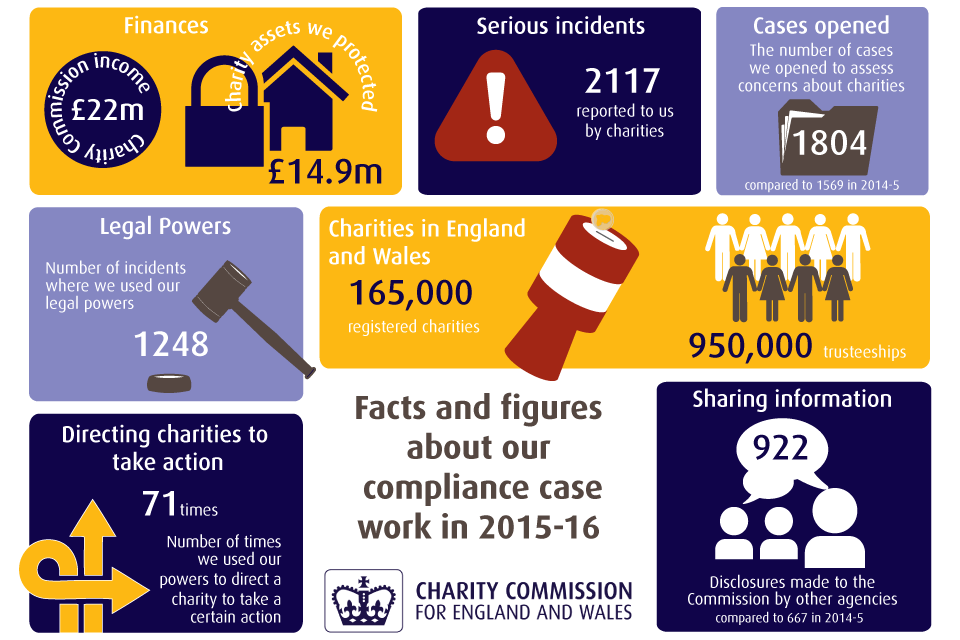

1.4 Key figures from our compliance case work in 2015 to 16

Charities in England and Wales

165,000 registered charities

950,000 trusteeships

Finances

Charity Commission income: £22 million

Charity assets we protected: £14.9 million

Serious incidents

Charities reported 2,117 serious incidents to us.

Cases opened

We opened 1,804 cases to assess concerns about charities. Compared to 1,569 in 2014-15.

Legal powers

Number of incidents where we used our legal powers was 1,248.

Directing charities to take action

Number of times we used our powers to direct a charity to take a certain action was 71.

Sharing information

We made 922 disclosures to other agencies. Compared to 667 in 2014-15.

For more statistical information about our compliance case work, see Annex 3, Statistical analysis 2015 to 16

2. Types of abuse and mismanagement

Only a relatively small proportion of registered charities have such serious problems that they become subject to a compliance case or investigation by the commission. But all charities can be vulnerable to abuse or mismanagement if their trustees have not put in place robust systems to protect their charity from harm, and crucially, if they don’t use them. Sometimes trustees may make honest mistakes that lead to further difficulties.

This section explains the principal types of abuse and mismanagement that we see in charities, based on our casework, and links to case study examples of our work in these areas.

The themes reflect the 3 key strategic risks facing charities, which we identified and prioritised in our published Risk framework:

- fraud, financial crime and financial abuse

- safeguarding issues

- abuse of charities for terrorist related purposes

They do not occur with equal frequency in charities – but when they do occur, the impact and damage they can have is significant, and not just on the individual charity in question, but on wider public trust and confidence in the charitable sector.

In addition we have identified 4 other themes which have featured in our compliance work over the past year and which are of wider interest (see section 3); they are governance issues (conflicts of interest, private benefit, and decision-making), charities facing financial distress, fundraising issues and registration compliance.

In this video, Michelle Russell, the commission’s Director of Investigations, Monitoring and Enforcement explains the work of her team and introduces the themes of the last year.

How to prevent serious mismanagement arising in a charity

Trustees can dramatically reduce the risk of serious mismanagement or abuse occurring in their charity by ensuring strong and robust governance. A key aspect of ensuring good governance is fulfilling the 6 key duties and putting robust controls in place. Not knowing the legal duties and our key guidance is not an excuse trustees can hide behind if things go wrong.

The 6 key duties of trustees are:

- ensure your charity is carrying out its purposes for the public benefit

- comply with your charity’s governing document and the law

- act in your charity’s best interests

- manage your charity’s resources responsibly

- act with reasonable care and skill

- ensure your charity is accountable

The essential trustee: what you need to know, what you need to do (CC3) explains what these duties mean in practice.

2.1 Financial mismanagement and financial crime

Our case work shows that, when trustees fail to manage their charity’s resources responsibly, their charity will be vulnerable to problems - most frequently financial mismanagement, financial abuse and financial crime.

Not all cases of financial mismanagement involve fraud or other criminality. But when we uncover evidence of potential criminality, we always share it with the police, and often work closely with them to help bring people who have committed crimes against charities to justice. See our strategy for charity fraud, financial crime and financial abuse for more detail.

All types of financial abuse have the potential to be highly destabilising for a charity. Monetary loss only forms part of the damage; financial abuse often causes wider harm, including to the charity’s reputation, and to morale among staff and volunteers.

Those who work in charities may see evidence of wrongdoing or abuse during the course of their work. In this video, Nigel Davies, the commission’s head of accountancy services, explains why whistleblowers should come forward and how they are protected when they do so.

Case studies

GYSO

We investigated prostate and testicular cancer charity GYSO after one of the trustees was convicted of theft. We were unable to contact the trustees despite repeated efforts. We used our formal powers of direction to obtain the charity’s bank statements and full donation histories from those hosting online donation platforms. Our investigation resulted in the removal of the charity from the register of companies, from our register and from 2 charity donation platforms.

Help Africa

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) contacted us to help their investigation into applications for Gift Aid by the charity. There was no evidence that the charity had spent funds to relieve poverty or otherwise help beneficiaries in Africa. As a result we removed the charity from the register.

Case work statistics

In 2015 to 16 concerns about financial abuse and/or financial mismanagement issues featured in:

- 46 new statutory inquiries, 34 completed statutory inquiries

- 227 new operational compliance cases, and 235 completed operational compliance cases

- 116 new monitoring cases

- 361 disclosures between us and other agencies

- 15 whistleblowing cases

In 2015 to 16 concerns about fraud, theft or the misapplication of funds featured in:

- 10 new statutory inquiries and 4 closed statutory inquiries

- 267 new operational compliance cases and 279 completed operational compliance cases

- 69 new monitoring cases

- 472 disclosures between us and other agencies

- 496 reports of serious incidents (RSIs)

- 18 whistleblowing cases

What we do when we uncover financial abuse or mismanagement

Our role as regulator is to ensure that:

- trustees comply with their legal duty to manage their charity’s resources responsibly

- any financial abuse or mismanagement is stopped

- trustees take steps to ensure the problems do not recur in the future

Our response will depend on the nature of each case, including how able and willing trustees are to take steps to put matters right.

If trustees co-operate, our role might involve setting an action plan requiring the trustees to carry out a review or introduce new financial controls within a certain timeframe.

However, in some cases, someone in the charity may be implicated in deliberate or reckless activity. In serious cases we may need to use our formal legal powers to protect the charity from further harm.

What we do to promote strong financial management in charities and compliance with the reporting requirements

As well as responding to concerns that arise in charities, we help prevent problems arising in the first place. This goes beyond the work of producing and updating guidance for trustees.

For example, we conduct themed reviews of charity accounts to check they comply with reporting requirements, to promote high quality financial reporting and to identify concerns about transparency.

We found this year that less than half the accounts and annual reports of the small charities that we looked at (with an income of £25,000 or less) were up to standard. Small charities who used our accounts templates were far more likely to prepare and submit high quality accounts. We would encourage small charities to use our template.

Larger charities with an income of over £25,000 have their accounts and annual reports displayed on the register of charities. A study of the accounts of larger charities shows continual improvement, although a quarter of those we examined still produced reports and accounts with major flaws. These include accounts that don’t balance, or that are not transparent enough; for example a quarter failed to provide the required disclosure on trustee remuneration in their accounts.

It is the trustees’ collective responsibility to ensure the financial returns are sent to the commission on time. Charities are sent multiple reminders about their approaching deadlines and also receive default notices when this is missed.

We warned charities in default and placed some of those that were in default in a class inquiry. We carried out further proactive work to address accounts and annual return defaulters and as a result of this work we identified:

- a worrying trend that some charitable incorporated organisations (CIOs) are already failing to submit their financial returns after registration

- that a number of charitable companies had not filed accounts as they were in liquidation or administration and so we updated our register of charities to make this clear to the public

- that charities that last declared an income of below £5,000 were more likely to be in non-compliance with their returns

We expanded our double defaulters class inquiry (those who do not file accounts 2 years running) to include a further 32 charities in 2015 to 16. By the year end, 14 had submitted their accounts, together with a further 13 charities from 2014 to 15. As a result, a further £15.5 million of charity funds is now accounted for and visible to the public on the register of charities.

Whilst the percentage of relevant charities filing accounts remains relatively static, following our enforcement work over the year, there were 12% fewer charities in default in March 2016 than in March 2015. And our particular focus on charities in default with an income of £100,000 or above has accompanied a decrease in the number of defaulters of charities in this income band by 20.5% in the same period.

Charity trustees ought to know it is their joint responsibility to submit accounts and returns on time. Our advice is to:

- submit accounts online

- not wait until the 10 month deadline but submit the documents as soon as they are read

- ensure you have a password to access the commission’s online services or ensure that you know who within the charity has the password

Our work on fraud

Tackling fraud is a key priority. We delivered our first national charity fraud conference in October 2015, hosted jointly with the Fraud Advisory Panel, for trustees and their charities, large and small. The key learning points from this event were collated in a new report, Tackling fraud in the charity sector.

We also successfully launched a new Charity Sector Counter Fraud Group (CSCFG), bringing together charities, professional bodies and other key stakeholders to agree actions to tackle fraud threats, including cyber fraud. Further work and a second conference have already taken place in 2016 to 17.

We also proactively monitor charities that show certain risk factors. For example, last year:

- we sought assurances from a sample of charities that had previously reported serious incidents relating to fraud, financial crime or safeguarding, that they have since acted on our advice

- we checked that charities that had declared nil income and expenditure on their annual return were accurate

- we acted on referrals and disclosures from other regulators where there were concerns about non-compliance

How a charity can help protect itself against financial abuse

There are some key steps trustees can and should take to help protect the charity’s funds, which in turn helps protect a charity against financial crime such as theft or fraud:

- set a business plan and budget and keep track of income and spend against it

- have robust and effective financial controls in place including robust but proportionate policies and procedures about managing income and controlling expenditure

- ensure trustees and senior management create the right culture, leading by example in adhering to the charity’s internal financial controls and good practice

- keep up-to-date and accurate records of all income and expenditure

- ensure trustees receive up to date, accurate and regular information about the charity’s finances

- prepare annual accounts and ensure they are audited and filed with the commission as required by law

- put in place appropriate safeguards for the protection of money, assets and staff if the charity operates outside the UK

Trustees can find more detailed information in our published guidance:

- The essential trustee: what you need to know, what you need to do (CC3)

- Internal financial controls for charities (CC8) and accompanying checklist

- Charity governance, finance and resilience: 15 questions trustees should ask

- Managing a charity’s finances CC12

2.2 Concerns about safeguarding

Trustees should proactively safeguard and promote the well-being and welfare of their charity’s beneficiaries. When abuse takes place whilst someone is under the care of a charity or by someone connected with a charity, for example a trustee or staff member, it harms the individuals involved, and can destroy public trust in both the charity and the whole sector.

Trustees must act in the best interests of the charity, act with care and skill, and manage their charity’s resources responsibly. This includes avoiding exposing the charity’s assets, beneficiaries or reputation to undue risk, and taking reasonable steps to protect beneficiaries from harm. Trustees should also be clear how any safeguarding incidents and allegations will be handled should they arise, and be prepared to justify how they have been handled. Trustees must also make sure that, if an incident does occur, they deal with it quickly and responsibly.

Safeguarding is a key governance priority. Even where work with children or adults at risk does not form part of the charity’s core work, trustees must be alert to their responsibilities to protect from harm all vulnerable groups with which the charity comes into contact. Charities that fund other organisations whose activities involve contact with children or vulnerable adults should also assure themselves that the recipient body has in place adequate safeguarding practices.

Any failure by trustees to safeguard those in their care, or to manage risks to them adequately, would be of serious regulatory concern and we may consider this to be misconduct or mismanagement in the administration of the charity.

Trustees should also know about their legal responsibility known as the ‘Prevent’ duty. You can read about this in the subsequent section. This is relevant to safeguarding because it is about having due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism.

Our role as regulator

Our strategy for dealing with safeguarding matters explains how we approach safeguarding concerns in charities and our regulatory role. The police and safeguarding authorities enforce safeguarding legislation and investigate individual instances of abuse. We focus on the conduct of the trustees and the steps they take to discharge their legal duties. On occasion, we may need to use our regulatory powers to ensure they do so

Our work in 2015 to 16: proactive work and new safeguarding guidance

This year we undertook a proactive piece of work, engaging with a sample of charities that had identified themselves as having vulnerable beneficiaries to look more closely at their policies and procedures. We found that most charities we contacted did have safeguarding policies and DBS checks in place, but had still ticked ‘no’ on the annual return, incorrectly suggesting to the regulator and the public that they did not have a safeguarding policy. For those that did not have one in place, we issued an action plan to remedy this quickly. We are following these up to ensure they make the necessary changes.

We are updating our safeguarding strategy and trustee guidance to clarify our regulatory role and trustees’ responsibilities and to include more emphasis on vulnerable adults, as opposed to only children. We are seeking advice from a reconvened Safeguarding Advisory Group, bringing together experts from a wide range of safeguarding specialist backgrounds including statutory authorities and charity sector expertise.

Unfortunately, our case work shows that some trustees fail to put in place the necessary policies and procedures and take steps to protect children and vulnerable people. The following case studies show what can go wrong and what lessons can be learnt.

Case studies

St Paul’s School

We opened an inquiry after a police investigation into allegations of historic abuse, and 3 reportable incidents in 2013; we found some weaknesses in the systems for trustees’ oversight of safeguarding. The trustees have since fully implemented an action plan to ensure they are in full compliance.

Rainbow rooms

We opened an inquiry into Rainbow Rooms, a charity supporting LGBT young people, after finding out that the CEO was under police investigation for an alleged sexual offence. The CEO had provided false information to the commission, the charity is now closed, and the CEO was sentenced to imprisonment for supplying false information and other offences.

Case work statistics

In 2015 to 16 concerns about current or historic safeguarding and beneficiaries at risk featured in:

- 1,131 reports of serious incidents - this is nearly half of all such reports

- 12 whistleblowing reports

- 163 new and 155 completed operational compliance cases

- 2 new inquiries and one completed inquiry

- 9 monitoring cases

- 187 disclosures between us and other agencies

What we do when we uncover safeguarding concerns

We will contact the police if there is a risk to a child or vulnerable adult. There may be instances where the police or another agency decides not to pursue a case, but the commission may still engage with the trustees because we have serious concerns about the charity, the conduct of its trustees or its systems to safeguard beneficiaries.

How to protect children and other vulnerable beneficiaries

Protecting beneficiaries involves putting in place internal procedures and policies that act as safeguards against abuse.

For example, a charity that works with children should:

- have a child protection policy – a statement explaining how the charity protects children from harm

- have effective whistleblowing procedures to ensure concerns can be raised

- put in place child protection processes which give clear, step-by-step guidance if abuse is identified or alleged

- carry out the appropriate DBS checks on staff, volunteers and trustees

- have policies and procedures to help prevent abuse happening in the first place, including around adult workers with one-to-one access to vulnerable people

Trustees can find further information about how to comply with safeguarding legislation and fulfil their duties as trustee; and the commission’s approach, in the following guidance:

- Protecting vulnerable groups including children

- Safeguarding children – detailed guidance

- Charity Commission Strategy for dealing with safeguarding issues in charities

2.3 Abuse for Terrorist related purposes

Some charities, like other types of organisations, can be at risk of abuse by extremists and terrorist groups. The risk is not equal from one charity to another; the risk depends on the nature of a charity’s work and where and how in the world they operate. However, where there are risks and abuse takes place, our role as regulator is to ensure trustees comply with charity law duties, take steps to protect their charity from harm and ensure that charity funds and property are used and applied properly. See our counter-terrorism strategy for more information.

Terrorist acts, and the funding of and support for terrorist groups and activities, are criminal matters. Where there are suspicions of terrorist abuse involving charities we always work closely with the police and other law enforcement agencies.

We are not a prosecuting authority and do not conduct criminal investigations. Our role is to help charities to prevent abuse from happening in the first place, and ensure abuse is reported and stopped, and that charities and their beneficiaries and assets are better protected in the future.

We work in partnership with charities operating in high risk areas around the world, where some charities work in difficult circumstances and where staff and volunteers risk their lives to deliver humanitarian aid.

This year we issued an alert to charities reminding them of the need to report any suspicions that their funds or assets may have been diverted to terrorist groups, both to the police, and to us.

Charities and their work can protect against extremism and terrorism and play a role in challenging hate, the ideology of terrorism and those that claim religious or other justification for terrorism. We want to help charities protect themselves and increase their resilience to terrorist abuse and we will work collaboratively with charities to raise awareness of risks and vulnerabilities, and to provide them with guidance and practical tools to manage the risks. Trustees must protect their charity against such abuse.

The level of risk facing individual charities will depend on their work and where they operate. For many charities the risks are low. The UK’s National Risk Assessment of money laundering and terrorist financing, (October 2015), assessed the risks of terrorist financing abuse arising in charities as medium-high.

Over the past year we successfully lobbied for changes to the Financial Action Task Force’s (‘FATF’) Recommendation 8 (on the abuse of non-profit organisations for terrorist financing). Charities alongside other voluntary sector organisations are covered by this. The recommendation and its accompanying Interpretive Note now reflect that the risk of abuse is not shared equally across all non-profit organisations. This means that a risk based approach is critical and FATF members should not view the entire non-profit sector as equally vulnerable to abuse.

Charities working in conflict zones have higher risk factors

If a charity provides aid in conflict zones, or where terrorist groups operate, the risks will inevitably increase and charities and their trustees must be vigilant to these.

Our approach to terrorist and extremist abuse is based on risk. From our work we assess the main areas of risks and vulnerabilities for charities from terrorist and extremist abuse are:

- fundraising methods– including cash, online and via social media

- movement of cash, goods and people

- diversion of aid internationally

- abuse or misuse of charitable assets, funds or goods in high-risk jurisdictions

- the use and misuse of a charity’s name, premises and resources to promote and facilitate extremist speakers and views

Charities in the UK can also be vulnerable to abuse

Charities working in the UK can also be vulnerable to terrorist abuse. People with extremist views, who encourage and support terrorism and terrorist ideology, have used charity events and speakers to make those views known, or used charities to promote or distribute extremist views or literature, including through online and social media.

Charities may promote or support views that may not be common place or may be controversial. But a charity involved in promoting, supporting or giving a platform to inappropriate radical and extremist views would call into question whether what it was doing was furthering the charity’s purposes and was for the public benefit.

Prevent - what does it mean for charities?

The Prevent duty applies to certain authorities, some of which are charities, and means they must have ‘due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism’ in the exercise of their functions. The duty is in section 26 of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015. ‘Specified authorities’ (described in Schedule 6 to the 2015 Act) include certain schools and childcare providers, and higher education providers.

Trustees of such charities should ensure that they are familiar with the Prevent duty and any supplementary guidance relevant to them, such as the Department for Education’s advice for school and childcare providers, or the Higher Education Funding Council for England’s guidance on how it monitors higher education institutions’ compliance with the Prevent duty.

Case studies

Concerns about a charity’s controls over its social media presence

We proactively identified a charity, through open source research. We had regulatory concerns about comments on the charity’s social media page – many of which were derogatory about refugees and Muslims. The posts raised concerns both about un-moderated comments made by third parties on the charity’s social media page, and about comments by charity representatives which appeared to condone or endorse these views.

We visited the charity to raise our concerns. As a result the trustees removed the offending posts and now moderate the charity’s social media page. The commission will monitor the trustees’ actions. The case remains open and ongoing to address additional regulatory concerns.

Funds raised for charitable purposes and held on charitable trusts in the name of Adeel Ul-Haq

In 2014, we opened a statutory inquiry into charitable funds raised by or donated to Mr Ul-Haq to assist those affected by the crisis in Syria. Funds were collected via social media. Our inquiry was not announced publicly at that time due to an ongoing criminal investigation and subsequent prosecution.

We took a series of regulatory actions to protect the charitable funds and secure their proper application, working collaboratively to support the police investigation and the prosecution. On 25 April 2014 we froze the bank account into which charitable donations had been paid. We later transferred the funds to another charity so that they could be used to assist those affected by the crisis in Syria. A further transfer of funds took place after the criminal prosecution concluded.

We removed Mr Ul-Haq as a trustee of the funds he held and he is now disqualified from being a charity trustee in the future.

Mr Ul-Haq was convicted in February 2016 of terrorism offences, under section 5 of the Terrorism Act 2006 (preparation of terrorist acts) and section 17 of the Terrorism Act 2000 (entering into or becoming concerned in a terrorist funding arrangement) and received 5 years’ imprisonment.

Case work statistics

In 2015 to 16, allegations made and concerns about abuse of charities for terrorist or extremist purposes, including concerns about charities operating in Syria and other higher risk areas, in which terrorist groups operate, featured in:

- 4 new inquiries

- 2 closed inquiries

- 21 reports of a serious incident

- over 70 visits and/or monitoring cases, to charities which were identified to be at greater risk of terrorist or extremist abuse by virtue of their activities or where they operate - some of these were proactively identified by us, or as a result of serious incident reports, complaints, or concerns raised in the media

- 8 operational compliance cases opened where there were, amongst others, allegations of abuse of charities for terrorist or extremist purposes, 6 of which were closed in the year

- 630 disclosures between us and other agencies out of a total of 2,332 during the year

How to protect a charity against abuse for terrorist related purposes

We expect trustees to be vigilant to ensure that their charity’s facilities, assets, staff, volunteers and other resources cannot be used for activities that may, or appear to, support or condone terrorist or extremist activities. The normal steps trustees take to ensure good governance and strong financial management will help protect charities against all kinds of abuse, including this. Trustees need to consider what procedures should be put in place to prevent others from taking improper advantage of the charity. What that means in practice will depend on the charity’s individual circumstances. Trustees should also take all necessary steps to ensure their activities or views cannot be misinterpreted.

Trustees can find further information about how to protect a charity in our published guidance:

- Charities and terrorism – chapter 1 of the online compliance toolkit, Protecting charities from harm

- Protecting charities from abuse for extremist purposes and managing the risks at events and in activities – chapter 5 of the online compliance toolkit, Protecting charities from harm

- Due diligence monitoring and end use of funds – chapter 2 of the online compliance toolkit, Protecting charities from harm

- Holding, moving and receiving funds safely in the UK and internationally – chapter 4 of the online compliance toolkit, Protecting charities from harm

- Regulatory alert reminding trustees of the requirement under section 19 of the Terrorism Act 2000 to report certain terrorist financing offences

3. Other issues we have seen on our casework

Four other themes have featured in our compliance work over the past year which are of wider interest, and these themes are covered in this section.

3.1Governance issues – unmanaged conflicts of interest, private benefit and poor decision-making

Good governance is key to charities’ success. Indeed, poor governance often leads to the 3 abuse areas. The strategic vision, oversight and evaluation that a board of charity trustees provides is not an ‘optional extra’ in a charity. Without it, trustees may put their charities at serious risk of abuse and also risk harming the quality of their service to beneficiaries. Most serious concerns we encounter in charities result from a basic failure of trustees to fulfil their 6 key duties, leading to poor governance.

Many of these duties are quite simple and straightforward but trustees must ensure they know and understand how to fulfil their responsibilities in their particular charity.

Governance problems can include failure to manage conflicts of interest, unauthorised private benefit (for example trustees or those they know benefitting personally from their involvement) and poor decision-making and record keeping.

Did you know?

Our public trust research this year showed that good management, or governance, is one of the 3 key drivers for trust in charities. We have written about what needs to be done by charities to improve governance in the sector, individually and collectively.

Core governance issues came up in 68% of our opened operational compliance cases and 65% of our closed cases. Two thirds of the whistleblowing cases we saw (98 out of 142) were related to governance issues.

Reports of serious incidents made by the charities themselves lag behind, with just under 10% of such reports being about governance issues (216 out of 2,217).

The role of the commission

It is our role to make sure that charities are governed in accordance with charity law, and to help trustees understand their duties, both through the guidance we issue and through our casework.

What we do to prevent and tackle serious governance concerns

Enabling trustees to run their charities effectively is one of the 4 priorities set out in our strategic plan 2015 to 18.

We are becoming more proactive in raising awareness of and ensuring trustees understand their legal duties and responsibilities, for example we doubled the reach of our updated core guidance for trustees, The essential trustee (CC3) in 2015 to 16,. We run awareness campaigns focused around specific areas of charity governance and trustee responsibility that we know need to be addressed, and work with partners to deliver these. We also send a quarterly newsletter to all trustees with all the news they need to know about our guidance, tools to help them and casework examples to disseminate lessons that can be learnt.

Our response where poor governance exists depends on individual circumstances; we take a risk-based and proportionate approach. Often, trustees recognise that poor governance or failures on their part have brought about problems and are willing and want to work with us to put matters right. However, when trustees have been negligent leading to significant loss or risk to the charity, or are unwilling or unable to respond appropriately, we may need to use our compliance powers to protect the charity.

Case work statistics

In 2015 to 16 serious governance concerns featured in:

- 42 new inquiries, 20 completed inquiries

- 216 reports of serious incidents

- 98 whistleblowing reports

- 898 new operational compliance cases and 854 completed operational compliance cases

- 105 new monitoring cases

- 140 disclosures between us and other agencies

Conflicts of interest

Trustees’ personal and professional connections can bring benefits to the work of a charity. However, they can give rise to conflicts of interest, which the trustees must manage responsibly. Trustees must identify conflicts of interest and where they exist, deal with and manage them appropriately, and record them, so that they are still making a decision as a board which is, and is also seen to be, in the best interests of the charity.

The conflict could be personal or professional (for example knowing someone that the charity might employ, or buy goods from, or whose views they might read more favourably), and does not necessarily involve any financial gain (see trustee or private benefit section). An example is taking the role of a parent governor in a school, where an individual may have to identify where their child may benefit in ways that others would not from making a particular decision - for example voting for more budget for music or for sport when their child plays sport – and therefore may decide not be involved in the discussion or vote on that issue.

The existence of a conflict of interest may not be a problem if it is properly addressed.

Case study

My Community UK

We investigated anti-poverty, health and education charity My Community UK to see whether conflicts of interest including related party payments had been effectively managed. There was also £130,000 unaccounted for and the original trustees were closely related, with payments made direct to their bank accounts and to companies owned by them. A conflicts of interest policy is now in place.

Odyssey Tendercare

We investigated this therapy centre for those with cancer and their carers, and linked hotel business, where we found multiple conflicts of interest. The charity was wound up and 2 remaining trustees removed/disqualified.

Concerns about unmanaged conflicts of interest

- 70 new operational compliance cases and 75 completed operational compliance cases

- 2 new inquiries

- 1 completed inquiry

- 15 new monitoring cases

Unauthorised private benefit

Another serious governance problem we see too often in our case work is unauthorised private benefit. This is when a trustee or someone connected to a trustee – for example a family member – benefits from their charity in a way that is not authorised under charity law. This authorisation must be by one of:

- the charity’s governing document

- the commission

- the courts

Even when personal benefits are authorised, it is important that trustees manage any resulting conflict of interest carefully. For example, if a trustee benefit relates to services that the trustee’s company provides at a competitive rate to the charity, it is important to ensure that the trustee is not part of discussions or decisions about whether and on what terms that arrangement should be continued.

Not all cases of unauthorised personal benefit involve deliberate abuse. Sometimes, the problem arises from good intentions, and the charity in fact benefits from the arrangement, perhaps because it receives goods or benefits at a discount. But even in such situations, the law says that if a benefit is not authorised, the trustee in question may need to account for their profit and pay over the sums involved. This is why it is so important to ensure that any benefits trustees receive are authorised.

A charity’s reputation can also be seriously damaged if trustees are seen to act outside their powers or take advantage of their position in a charity in obtaining personal benefits.

Case studies

Nice Time

Nice Time operates an ice rink. Two of the charity’s trustees were benefiting from payments made by the charity’s trading subsidiary and these payments were not authorised. When we investigated, they stepped down and the charity was quick to make changes.

Surf Action

Surf Action is a military charity based in Cornwall. We investigated allegations that the directors and trustees received unauthorised private benefit in the form of salaries. The charity had appointed its employees as ‘directors’ which in law meant that they became charity trustees. The directors/trustees did not realise and appointed other ‘trustees’, who had no standing in law. As a result of our work, the directors stepped down, the trustees resigned, new trustees were found and the charity is now operating effectively.

Deafinitions

Deafinitions’ accounts showed 3 of the charity’s 4 trustees were benefiting privately from the charity, contrary to the charity’s governing document. We found the charity trustees were being employed as staff members because no external candidates had come forward. We regularised this situation, but insisted that the majority of the trustees should be unpaid, so they could review payments to trustees and ensure they were in the charity’s best interests.

Trustee pay, and concerns about trustee or other private benefits featured in:

- 5 new statutory inquiries

- 1 completed statutory inquiry

- 10 whistleblowing reports

- 130 new operational compliance cases and 132 completed operational compliance cases

- 23 new monitoring cases

Decision-making and recording decisions

Collective trustee decision-making that is properly recorded is at the heart of good governance. Good decision-making involves, among other things, acting in good faith and exclusively in the charity’s interests, acting within your powers, managing conflicts of interest, informing yourself properly and seeking appropriate advice where relevant. In every case, trustees must record how they came to the decision, so that they can evidence their approach.

Our case work shows that poor decision-making and record-keeping can lead charities into serious mistakes or even mismanagement.

Individuals applying significant control or influence can hinder good decision-making

Sometimes in charities, individuals or groups of individuals – including staff members take over control or become too influential and make decisions that should be taken collectively.

This can be bad for the charity, even if the individual or group means well, as decisions may not have the buy-in of the rest of the board; decisions can be taken that are not in the best interests of the charity perhaps because the trustees are not sufficiently informed; and the risks of a particular course of action may not be properly considered, while irrelevant factors may be allowed to influence decisions.

Individuals who exercise significant control or influence sometimes have ulterior motives and go on to abuse a charity for personal gain.

In the following case studies, when we looked into the decisions the trustees had made, we found they had taken and documented the appropriate steps to make their decisions, even if these were controversial.

Case studies

Scope

Scope had decided to exit 11 of their 35 care homes. It is up to trustees to make decisions about how best to achieve their charity’s objects, but we checked the decision-making process. There had been consultation with beneficiaries, and while it would be a controversial move, we were satisfied that the trustees had taken external advice and properly considered the impact of their decision.

St Bees School

St Bees School, an independent day and boarding school in West Cumbria, was closed suddenly. We looked into whether there had been misconduct or mismanagement in the administration of the charity. We found diminishing numbers of students from 2008. Parents started a rescue plan, which the trustees considered but rejected. While the governors might have acted faster, or differently, we found they did so in good faith.

Concerns about trustee decision making featured in:

- 78 new operational compliance cases and 73 completed operational compliance cases

- 13 new monitoring cases

Trustees can also find further information in our governance guidance:

- The essential trustee: what you need to know, what you need to do (CC3)

- Charity governance, finance and resilience: 15 questions trustees should ask

- The hallmarks of an effective charity (CC10)

- It’s your decision: charity trustees and decision making (CC27)

- Conflicts of interest: a guide for charity trustees (CC29)

- Reporting serious incidents – guidance for trustees

3.2 Charities in financial distress

In 2015 to 16 we saw a number of charities in financial distress, with many charities experiencing reductions in funding from central and local government sources, charged for services or voluntary income.

Good financial planning, diversified revenue and policies to protect charity funds may mean that trustees can avoid financial distress situations or pull their charity out of them, but unfortunately sometimes the worst will happen and trustees need to know what to do.

We cannot act to stop a charity closing down or intervene in the management and administration of charities in financial distress, however we provide regulatory advice to trustees on how to comply with their duties and manage the decisions they have to take, as well as take enforcement action when we find trustees have failed to comply with their duties.

Financial distress

The closure of a number of charities during the year highlighted the importance of trustees managing financial difficulties well and the negative impact the collapse of high profile charities can have on public trust and confidence in charities more widely. We therefore included a theme of charities at risk of financial distress in our programme of monitoring and inspection visits. We looked at 10 charities in financial distress.

We also carried out a proactive scrutiny and review of various charity accounts that signalled the charity may be in financial difficulty. We reviewed 94 sets of accounts of larger charities where the audit reports flagged financial difficulty.

Not surprisingly, the ongoing challenging financial environment was the underlying factor behind many of the charities’ difficulties. The specific reasons overlapped, to some extent with the issues highlighted by the auditors, although a wider range of factors emerged. These included dependence on public sector funding, set up or restructure costs, pension scheme deficits and unplanned overspends.

Most charities were responding by trying to generate more income, for example through increasing take-up of their services, diversifying sources of income or increased fundraising. Those faced with a specific risk such as a pension deficit were working on managing it. A smaller number of charities were looking for efficiencies by reducing operating costs. The most seriously affected were either restructuring or considering winding up.

The reports did show that those charities who take early, pragmatic steps to actively identify and manage their financial difficulties will secure better outcomes for their charities and their beneficiaries.

In this video, Kate Waring tells us about the commission’s work on charities in financial distress and the key lessons for all charities.

What can trustees do to protect a charity from financial distress?

- diversify income where possible

- put robust policies and procedures in place to manage charity finances, including building up appropriate financial reserves

- recognise early signs of financial distress and take early and proactive steps to deal with the issues, for example reducing spending plans, disposing of property assets, seeking alternative revenue sources and building up appropriate financial reserves

The following case study is a good example of a charity taking timely action when financial distress threatened.

Case study:

Volunteering Matters

This charity had a large pension deficit and the loss of a substantial government grant, but had already taken significant positive steps over the last 2 years to put the charity on a more stable footing. This included taking relevant professional advice and putting in place a transformation plan to streamline the organisation and help build reserves.

In 2015 to 16 concerns about financial distress featured in:

- 2 new statutory inquiries

- 2 completed statutory inquiries

- 18 new operational compliance cases, and 16 completed operational compliance cases

- 10 new monitoring cases

Trustees can read our guidance on financial resilience, revised in 2015 to 16, and an overall guide to planning and managing difficulties on GOV.UK:

- Charity reserves: building resilience CC19

- Managing a charity’s finances: planning, managing difficulties and insolvency CC12

3.3 Fundraising

In the summer of 2015, charity fundraising came under a period of sustained scrutiny, in the press, in parliament and by the public.

The issues of particular concern included:

- high numbers of mailshots to some donors

- swapping and sharing of donors’ details that may have breached the law

- targeting of elderly and potentially vulnerable donors

- aggressive telephone fundraising by professional fundraising agencies

- charities failing to observe telephone and mail preference service requests

Sir Stuart Etherington, the Chief Executive of NCVO, led a review of the self-regulation of fundraising in the summer of 2015.

Regulating Fundraising for the Future was published in September 2015 and recommended a new body to regulate fundraising to take over responsibility for setting standards for fundraising in the Fundraising Code, and adjudicating fundraising complaints against the Code.

We have helped and supported the establishment of the new body, The Fundraising Regulator, which was officially launched in July 2016, including seconding a member of our staff to the Regulator.

Our role in regulating fundraising by charities

Charity fundraising is self-regulated, and all complaints about fundraising practices in England and Wales should go to the Fundraising Regulator first.

We expect charities that fundraise to do so in a way which protects their charity’s reputation and encourages public trust and confidence in their charity. Where there is evidence of a serious risk to the charity or to public trust and confidence, or serious concerns about the conduct of trustees, we will intervene.

We work closely with the Fundraising Regulator to ensure that referrals are passed efficiently between the 2 bodies and that instances of poor fundraising practice are dealt with as swiftly as possible. A Memorandum of Understanding has been signed that sets out how the commission and the Fundraising Regulator will coordinate their respective regulatory roles.

Case work statistics

In 2015 to 16 concerns about fundraising issues featured in:

- 33 serious incidents reported to the commission

- 82 opened operational compliance cases, 82 closed operational compliance cases

- 63 monitoring cases

- 114 disclosures between us and other agencies

Case studies

Bait Ul Mall

Bait Ul Mall, a charity that collected money to help orphans in Pakistan, allegedly gave unauthorised funds to trustees. We investigated, and found inadequate record-keeping and that money passing through the bank accounts was not reported in the accounts. We found no evidence of private benefit. There is now a new, more robust approach to record-keeping, cash collections and framework for trustee benefits.

Age UK

Age UK aims to promote charitable purposes for the benefit of older people. We became involved following media reports suggesting the charity received £6 million a year from energy supplier E.ON to promote a tariff to older people that was more expensive than other tariffs available. The outcome was that Age UK has commissioned a review to ensure its trading activities do not undermine its charitable purposes.

What we do to prevent and tackle concerns about charities’ fundraising activity

With charity fundraising in the spotlight, it is more important than ever for trustees to fulfil their legal duties and responsibilities in overseeing their charity’s fundraising.

In June 2016, to support trustees and help them avoid problems, we updated our guidance for charity trustees about fundraising from the public. Charity fundraising: a guide to trustee duties (CC20) sets out 6 principles to help trustees comply with their legal duties:

- plan effectively

- supervise your fundraisers

- comply with fundraising law

- protect your charity’s reputation and other assets

- follow recognised standards

- be open and accountable

It includes a checklist for trustees to evaluate their charity’s performance against the legal requirements and good practice recommendations set out in the guidance, and details the types of fundraising-related problems that may require our intervention.

Alongside our guidance, the Institute of Fundraising has published practical guidance which trustees may find helpful.

3.4 Registration compliance

We promote trust and confidence in charities by only registering organisations that pass the legal tests for a charity, as set out by Parliament in the Charities Act. We make a formal assessment of all applications received against our risk framework, a process which includes taking into account any information already held about trustees of the organisations applying. In 2015 to 16 we undertook 13% more such checks than the previous year.

Where we are not satisfied that an organisation is a charity, we will not register it. In 2015 to 16 only approximately 60% of the 8,198 applications received were registered. The bulk of the remainder were either refused or did not pursue their application after we requested further information.

By law, whilst we must register charities who raise governance or compliance concerns, we use the registration process to better identify these charities and have introduced better monitoring to follow up as appropriate. We actively monitor newly registered charities where we have concerns about them, for example low levels of charitable activity, or charities that operate in high risk areas internationally, and opened 49 such monitoring cases in the last year. We also ensure new trustees comply with the law as well as help promote public trust and confidence in charities by ensuring promises made at registration stage which enable an organisation to be registered and operate as a charity are kept.

We improved our registration process, by launching a new system, which helps trustees to register faster by ensuring all the information we need to make a decision is provided from the outset. This also helps us identify concerns or problems with applications. Before putting this in place only approximately one-third of cases could be classified as ‘low-risk’ and registered with the need for minimal further checks; currently approximately two-thirds are in this category. This has freed up our resources to concentrate our resources on higher risk cases.

Case studies

Preston Down Trust

We carried out post-registration monitoring of The Preston Down Trust, a charity that is part of the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church. We found the trustees were taking steps to ensure this was a well-run charity, although there were some points for the trustees to address to improve openness and transparency.

Holmewood Animal Rescue

This was another post-registration monitoring case where we looked at issues around land and property, as the charity operated from property owned by some of the trustees; they had promised to resolve it after registration, but more work was needed to ensure there were no conflicts of interest.

Case work statistics

In 2015 to 16 concerns about registration featured in:

- 28 opened operational compliance cases, 31 closed operational compliance cases

- 49 monitoring cases

- 88 disclosures between us and other agencies

Trustees can read more about our guidance on registration, including choosing a charity’s objects, governing constitution and naming a charity: