Tampon Tax Fund evaluation: appendices

Published 6 June 2023

Appendix 1: Summary of TTF logic model

1.1 Introduction

This appendix provides a summary of the TTF logic model. The TTF logic model was developed by Kantar Public in collaboration with DCMS as part of the TTF evaluation scoping phase. The logic model provides the underpinning theory and framework for the evaluation design.

1.2 About logic models

A logic model illustrates and describes how and why a programme is expected to achieve its specified outcomes and impacts. Key components are mapped out onto a chain of results, and the interactions or logic between components are explored.

A logic model can guide and inform the scope and remit of an evaluation, for example by identifying programme activities, deliverables, outcomes and impacts to provide the foundations of an evaluation framework and plan. For this reason, developing a logic model for TTF was a key deliverable for this scoping phase. The logic model has directly informed the design and development of the proposed TTF evaluation.

1.3 TTF logic model development

Kantar Public used the insights collected in the evaluation scoping phase to develop a logic model. Once created, a workshop with stakeholders was held to work through each element of the logic model and to agree on the different design options and preferred design approach.

1.4 TTF logic model overview

The logic model has been developed to understand the approach taken by TTF to meet its core aim(s) and intended impacts. The key components of the logic model are as follows:

-

Introduction: the overarching purpose, remit and underpinning contextual factors that have informed the overall design of the Fund

-

Fund delivery models: the models by which the funding has been distributed to organisations to reach and benefit end beneficiaries (women and girls)

-

Interventions: the types or categories of activity and intervention(s) that Fund recipients delivered in order to support women and girls

-

Project defined outcomes and impacts: the specific outcomes and impacts that individual projects are seeking to achieve, as defined by Fund recipients themselves. At a Fund level, no specific outcomes were mandated to Fund recipients

-

Fund impact: the overarching impacts that the Fund is aiming to achieve

1.5 Introductory component of the TTF logic model

The first section of the logic model presents the key contexts framing and underpinning TTF. These factors are presented as the first element of the logic model because they inform the shape and design of TTF and are integral context for the proceeding elements.

Key to this origin and purpose was the intention to keep the TTF focus areas and remit broad, allowing organisations in the not-for-profit and community sectors to identify the key issues and challenges to be addressed. Core themes were identified for each year of Fund delivery with the intention of ensuring a diversity of organisations and issues being funded, as well as to address ministerial priorities at the time. The themes addressed by TTF over the course of its delivery were:

-

violence against women and girls

-

general theme

-

mental health and wellbeing

-

young women’s mental health

-

rough sleeping and homelessness

-

music

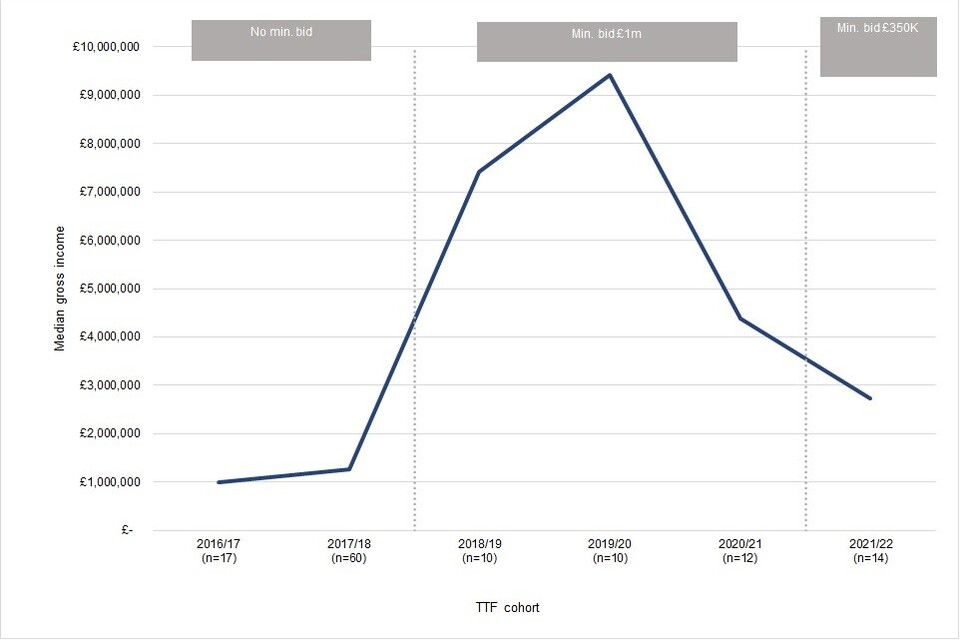

The eligibility criteria specified that bid applications must come from registered charities, and benevolent and philanthropic organisations, with proposed activity focusing on women and girls (notably, organisations did not have to be specialists in the women’s and girls’ sector, but were eligible for funding as long as their proposed activity benefited women and girls). Organisations were required to apply for funding valuing at least £350,000 and with a bid not exceeding 50% of the organisation’s income. This value varied across years of delivery; there were initially no minimum criteria, then there was a £1 million minimum, which was then changed to £350,000 in the 2021/2022 round of funding.

1.6 Fund delivery models

The following four funding models were identified.

Model 1: An intervention delivered that is accessed directly by the end beneficiary. Here, one organisation or a partnership of organisations puts the funding towards providing frontline and direct support to women and girls.

Model 2: The delivery of intermediary capacity building activities that subsequently support end beneficiaries. Here, one organisation, or a partnership of organisations, puts the funding towards capacity building activities such as training for professionals, or towards wider capacity building activities such as shared learning spaces.

Model 3: Funding is given to an intermediary grant-maker, which delivers an intervention that is accessed directly by the end beneficiary. Here, an intermediary organisation receives TTF funding and then delivers their own tender process to provide funding to a wider set of organisations. These onward grant recipients then put the funding towards providing frontline support to women and girls.

Model 4: Funding is given to an intermediary grant-maker, which delivers intermediary capacity building activities that subsequently support end beneficiaries. Here, an intermediary organisation receives TTF funding, and then delivers their own grant-making process to provide funding to a wider set of organisations. These onward grant recipients then put the funding towards capacity building activities.

1.7 TTF interventions

The TTF interventions can be grouped into seven main types. The first three are identified as activities that can form the ‘intermediary’ stages of the delivery models outlined above: activities that are not delivered directly to women and girls, but which ultimately provide them with benefits. These are:

1. Onward grant-making: Funding received is redistributed as smaller grants to wider organisations, often with the same or more focused aims to TTF and with a focus on reaching small and medium-sized community organisations without direct TTF access. Onward grant-making will always lead into a wider set of interventions that fall into one of the six other category types outlined below.

2. Training: Training is provided to professionals and organisations, or people with lived experience, to better equip them to support women and girls. Training provided to women and girls with lived experience is multi-purpose and may also be seen as an intervention that provides frontline support and education opportunities to end beneficiaries.

3. Capacity building: Consultancy and support is provided to an organisation to improve practices that will ensure better support is provided to women and girls. These interventions may include activities such as shared learning spaces and networks, support for implementing best practice, reviewing or rolling out organisational policy, provision of digital skills, etc.

The remaining four intervention types focus on the delivery of frontline support to end beneficiaries (women and girls). These are:

4. Signposting and awareness raising: Signposting is provided to women and girls to raise awareness and improve access to support services. This type of intervention seeks to strengthen support pathways and increase access to support, as well as to enable joined-up working.

5. Frontline services: Support and services are provided to women and girls. Examples of frontline services include the provision of one-to-one or group support, peer/community support, coaching/mentoring, housing and accommodation, etc.

6. Education: Provision of education and/or training to support women and girls’ knowledge and skills development, for example language skills.

7. Resource equipment and technology: The provision of physical or digital equipment, tools or resources used in the delivery of support for women and girls. Examples of this could be providing bikes, sanitary products, online services, educational resources or digital content (including apps).

These first three intervention types may support the delivery of the remaining four intervention types, although the latter can also be delivered independently. Fund recipients may deliver just one, or multiple, intervention types within their funded project.

1.8 Project defined outcomes and impacts

Outcomes and impacts have been identified across three levels: sector, organisational and individual. Outcomes and impact also cut across short-term outcomes, long-term outcomes and project impacts, where:

-

short-term outcomes are defined as measurable outcomes directly attributed to intervention delivery and which are felt or experienced immediately/soon after the intervention is accessed or delivered

-

long-term outcomes are measurable outcomes directly attributed to intervention delivery that are felt or experienced in the long term after the intervention is accessed or delivered – for example, outcomes you would expect to see/feel/experience in the months after the intervention has ended)

Project impacts, in this context, are higher level goals that the project is expected to contribute towards, but which cannot be directly attributed to intervention delivery.

The first component is sector level, whereby outcomes and impacts are expected in the voluntary and community sector (VCS) overall. The main short-term outcome at the sector level is improved sector partnership and organisational linking. In the longer term, this leads to an outcome of improved sector knowledge and increased assets, which projects expect to have an impact on the sector overall by supporting a shift in sector responses towards preventative work.

The next component is the organisational level, where TTF projects create outcomes and impacts for the funded organisations and their delivery partners. Projects identified two common short-term outcomes at the organisational level: improved ability/skill to support women in need and improved access to resources, and guidance and shared learning (also an individual level outcome – see below). These short-term outcomes do not lead to any organisational outcomes or impact but support longer-term sector-level outcomes and impact by improving sector knowledge and assets. Notably, some outcomes and impacts sit across multiple levels.

The final component is the individual level, which involves outcomes that impact directly on individuals and their lives, with a specific focus on the end beneficiaries: women and girls.

A common short-term outcome for individuals was improved access to resources, guidance and shared learning (also an organisational-level outcome – see above), which leads to a longer-term outcome of improved physical and mental health management for women and girls.

A second common short-term outcome was improved access to quality support for women and girls in need, which projects expect to lead to increased help-seeking and improved confidence in the longer term. These outcomes are expected, in some cases, to be a result of organisational and/or sector-level outcomes; for example, improved skill in organisations would support improved access to quality support for women and girls.

Ultimately, projects focused on the individual level expect these outcomes to create two potential individual level impacts: a reduced risk or experience of violence and harm, and/or women and girls being empowered to act as their own agents.

1.9 Fund impact

Ultimately, these project-level outcomes and impacts are expected to help TTF achieve broad, overarching impacts. Three core impacts have been identified by stakeholders and projects, focusing on impact for end beneficiaries (women and girls) and at the sector level. These are as follows.

-

TTF intends to have a positive impact on the lives of women and girls, especially those facing disadvantage and harm.

-

TTF intends to have a positive impact on the types of initiative available to women and girls, through a strengthened offer of locally relevant initiatives provided by specialist and community organisations.

-

TTF intends to create a lasting impact on the VCS through the provision of sustainable and/or ‘snowball’ interventions (new interventions that emerge from, or are inspired by, the original funded activities), increased sector resources and knowledge, and improved sector networks.

Appendix 2: Findings from the review and synthesis of applications for TFF funding, project monitoring data and reported evaluation evidence

2.1 Introduction

This appendix sets out the findings of the review of the documentation from successful applications for TTF funding, project monitoring forms and End of Grant reports. The full review used data from all 137 successful project applications and built on the initial review of 33 successful applications (all 14 from the 2021/2022 cohort and a sample of 19 from 2016 to 2020). The review did not include any analysis of data from unsuccessful applications, so comparisons between successful and unsuccessful applications was not possible. The analysis in this section therefore only refers to successful applications, and these are referred to interchangeably as ‘applications’ or ‘successful applications’.

The review also considered the self-reported data submitted in End of Grant project reports. In some areas (for example, related to outcomes and impacts), data from both sources was incomplete and/or of varying quality, type and format. Projects funded in 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 did not provide any information on final outputs, outcomes or impacts as their projects were ongoing. These factors limit the analysis, and findings are not intended to be generalisable to the Fund as a whole.

2.2 Methodology

The objectives of the review were to understand the scope of TTF and its funded projects; combinations of delivery models used; combinations of intervention categories proposed; project monitoring and evaluation plans; proposed and reported outcomes and impacts; and lessons learned.

A rapid review of 14 project applications was used to develop an analytical framework, which captured information about the applications (location, funded amount, key contacts, details of additional funding, delivery timeline, activities); the proposed interventions (including budget, beneficiaries, mode of delivery, new or existing interventions and expected numbers); plans for monitoring and evaluation; and intended and reported outcomes and impacts. The framework was tested and a review of 33 applications conducted at the evaluation design stage to inform the development of a TTF logic model for the evaluation. The full application review in the mainstage evaluation built on this analysis, using data from all 137 successful applications. Project documents (including End of Grant reports) were reviewed and the framework populated before key findings were synthesised using the framework.

The data and analysis in this appendix relate to direct TTF grantees only.

2.3 Application review findings

The following sections present the findings of the application review, covering key information on the funded organisations and the interventions they delivered, the findings on TTF delivery models and intervention categories developed as part of the TTF logic model, and the expected and reported project outcomes/impacts.

2.3.1 Funded organisations

All 137 successful applications were from not-for-profit organisations or consortia, as intended in the TFF selection criteria. Organisations varied in size from small, locally focused or specialist to larger national organisations, with a wide range of specialisms and areas of focus (Table 1) below.

Table 1: Specialisms of funded organisations

| Specialisms of funded organisations |

|---|

| Homelessness; mental health; violence against women and girls (and addressing trauma); working with minority communities and groups (such as migrant and refugee women and girls, and women and girls with lived experience of the criminal justice system); and participation in sport; financial and money advice; care and the caring community; modern slavery; gambling; pregnancy, maternal health and maternity support, including for miscarriages; disability; and education, employment and skills, including improving literacy skills |

The geographic areas covered by the applications funded included all areas of the UK (Table 2). Over a quarter of all applications focused on very local issues and/or coverage.

Table 2: Percentage of applications covering different geographic areas

| Whole of UK | Combination of two or three countries | England only | Scotland only | Wales only | Northern Ireland only |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 12% | 50% | 10% | 4% | 4% |

The value of successful applications ranged from £16,500 (to a local organisation providing sporting opportunities for those with disabilities) to £3,545,000 (to a network of community foundations to deliver onward grants at a local level). The distribution of proposed spend is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Successful applications by value

| Value (GBP£) | Percent of applications |

|---|---|

| Up to £50,000 | 4.35% |

| £50,000 to £99,999 | 13.77% |

| £100,000 to £249,999 | 25.36% |

| £250,000 to £499,999 | 17.39% |

| £500,000 to £999,999 | 7.25% |

| £1,000,000 to £1,999,999 | 26.09% |

| £2,000,000 and over | 5.07% |

All seven applications with values over £2 million focused on providing onward grants to other organisations.

The seven applications of this size came from just five organisations and had a total value of £19,473,662, or 22.5% of the total TTF funding.

Three of these five organisations had multiple other successful applications: one organisation had four separate applications (a total funding of £8,576,175), and the other two organisations had two successful applications each (the total funding to these two organisations was £6,954,000 and £3,106,855 respectively).

Through their eight successful applications, between them these three organisations received over 21% of the total TTF funding.

While this shows that a significant proportion of the total TTF funding was awarded to a few organisations as direct grantees, it was then provided to a large number of other organisations as onward grantees (while the exact number of onward grantees is difficult to establish from the review of applications, monitoring data and End of Grant reports, a public data analysis shows 1,230 organisations received onward grants).

The largest number of successful applications had budgets ranging between £1 million and £2 million and did not involve onward grants. These had the greatest number of successful applications (36 applications, or 26%) and larger budgets, and accounted for over 50% of all funding.

Overall, almost 75% of TTF funding went to the 31% of successful applications with budgets of over £1 million.

The 25% of successful applications with values between £100,000 and £250,000 (the second largest number of applications) received 6.6% of total TTF funding (or £5,750,025).

Successful applications with budgets under £100,000 (18% of successful applications) received around 2% of total TTF funding (about £1.73 million).

Applications proposed to address a wide range of issues, summarised in Table 3.

Table 3: Issues addressed in applications

| More common issues addressed in applications | Less common issues addressed in applications |

|---|---|

| Lack of access to services for women and girls, including the need for investment in equipment and resources to support service delivery Lack of trauma-informed approaches in services, including the need for support for Black and minority groups, women and girls with disabilities, refugees and others experiencing violence or abuse Lack of funding to support women and girls affected by abuse and violence Limiting skills, confidence and knowledge of frontline staff to work across issues like domestic violence |

Lack of support for women during pregnancy, including miscarriage and overall maternity care Low levels of help-seeking among women affected by problem gambling Lack of adequate housing services, e.g. female offenders and victims of modern-day slavery Low levels of access to education and skills for women and girls in areas of high deprivation Absence of clear support pathways for those who have experienced intimate image abuse Lack of support for carers, such as those caring for young women and girls with eating disorders Lack of equipment/resources for audiences to address specific issues, such as free sanitary products to address period poverty |

2.3.2 Delivery models

In the scoping phase, Kantar Public identified four models through which TTF funding was delivered to reach and directly benefit women and girls. These are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Fund delivery models

| Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | Organisations or partnerships directly provide frontline services and support to women and girls | Organisations or partnerships provide capacity building activities to improve intervention quality | Organisations act as intermediary grant-makers and onward fund delivery bodies to deliver activities | Organisations act as intermediary grant-makers and onward fund capacity building activities to improve service quality |

| Percentage of awards | 41% | 45% | 9% | 14% |

Successful applications using one delivery model were distributed across all application values, although applications using model 1 were more likely to be of lower value (< £500,000) compared to model 4 (> £1 million).

Figure 3: Distribution of applications using single delivery models by application value

Percentage of applications

| Value (GBP£) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up to £50,000 | 4.17% | 0.00% | 0.83% | 0.00% |

| £50,000 to £99,999 | 10.00% | 5.00% | 0.83% | 0.00% |

| £100,000 to £249,999 | 13.33% | 12.50% | 1.67% | 0.00% |

| £250,000 to £499,999 | 6.67% | 6.67% | 0.83% | 0.83% |

| £500,000 to £999,999 | 1.67% | 3.33% | 0.00% | 2.50% |

| £1,000,000 to £1,999,999 | 5.00% | 12.50% | 1.67% | 5.83% |

| £2,000,000 and over | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2.50% | 1.67% |

Most applications (around 87%) only involved one delivery model. However, the four models were not exclusive, and the remaining 13% of applications involved various combinations of two models within their overall approach. No successful applications involved combinations of three or four models.

Of the applications using two models, 50% involved combining models 1 and 2 and 31% involved combining models 2 and 4. Model 2 (capacity building of other organisations) was used in combination with another model in over 87% of the successful applications using multiple delivery models. No successful applications combined model 1 with either model 3 or model 4.

Figure 4: Delivery model combinations used in successful applications

| Combinations of bid delivery models | Models 1 and 2 | Models 1 and 3 | Models 1 and 4 | Models 2 and 3 | Models 2 and 4 | Models 3 and 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of applications | 50.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 6.25% | 31.25% | 12.50% |

2.3.3 Intervention categories

Within the four delivery models, the TTF logic model included seven categories of intervention that Fund recipients delivered to support women and girls.

Onward grant-making: Funding received is redistributed as smaller grants to other organisations, aligned with the themes of TTF and with a focus on reaching small and medium-sized community organisations without direct TTF access. Onward grant-making leads onto a wider set of interventions falling into one of the six other categories outlined below.

Frontline services: Support and services are provided to women and girls, such as providing one-to-one or group support, peer/community support, coaching/mentoring, accommodation, etc.

Capacity building: Support is provided to an organisation to improve practices and ensure improved support for women and girls, such as shared learning and networks, support for implementing best practice, revising organisational policy and digital skills provision.

Training: Training is provided to professionals and organisations, or to women and girls with lived experience, to better equip them to support women and girls in need. Training for those with lived experience also included frontline support and education opportunities to beneficiaries.

Signposting and awareness raising: Signposting is provided to women and girls to raise awareness and improve access to support services. This intervention seeks to strengthen support pathways and increase access to support, as well as to enable joined-up working.

Education: The provision of education and/or training is delivered to support the knowledge and skills development of women and girls, for example language skills.

Resources, equipment and technology: This is the provision of physical or digital equipment, tools or resources delivered to support women and girls. Examples of this include providing bikes, sanitary products, online services, educational resources or digital content/apps.

The first three categories are interventions that support women and girls via intermediary activities, while the last four are interventions delivered directly to women and girls. Successful applications included these intervention categories either individually or in combination. The most common categories were the direct delivery of frontline services and wider capacity building interventions. The least common interventions were signposting and awareness raising interventions and training.

Figure 5: Frequency of intervention types within successful applications

Percentage of applications.

| Intervention categories | Onward grants | Training | Wider capacity building | Signposting and awareness raising | Frontline services | Education | Resources, equipment and technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of applications | 23.91% | 15.22% | 37.68% | 11.59% | 57.25% | 22.46% | 14.49% |

Delivering frontline services directly to target groups was the most common intervention category, included in around 58% of successful applications. Almost 90% of these focused on three main types of intervention, as follows.

-

Targeted support services to address VAWG: These were provided in around half of successful applications. They included rape crisis trauma-informed holistic support for survivors of sexual violence.

-

Other support services (mental health or financial advice): These were provided in around 45% of successful applications. They included evidence-based guidance to help carers support family members with eating disorders, and most commonly targeted groups of women and teenage girls from ethnic minority backgrounds at risk of exclusion.

-

Outreach programmes: These were included in almost 18% of successful applications and focused on issues affecting women and girls (for example, supporting ‘link workers’ to support and strengthen relationships between women’s centres and prisons), most often targeting specific groups including women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds and (ex-) offenders.

Most successful applications involving frontline services (around two-thirds) also involved another intervention category, primarily education, training and/or wider capacity building interventions. Around 35% of successful applications involved frontline delivery alone.

Figure 6: Percentage of frontline service types in successful applications delivering services alone

| Frontline service intervention type | Percentage of applications |

|---|---|

| Targeted VAWG support services | 43.75 |

| Other support services (mental health, money advice) | 43.75 |

| Outreach programmes | 6.25 |

| VAWG plus other support services | 3.13 |

| VAWG plus other support services and outreach programmes | 3.13 |

Wider capacity building interventions were included in 38% of applications. These involved building the capacity of other organisations or networks to enable them to deliver services and programmes. For example, one project team incorporated capacity building in their onward grant-making activities by providing one-off payments to onward grantees to support digital skills capacity building. More common audiences were the staff of NHS teams and onward grantees, but other frontline services were also targeted. For instance, one organisation worked with 20 police forces across England and Wales to increase the number of specialist officers trained to investigate, assess and manage risk and enhance safeguarding regarding honour-based abuse and forced marriage.

Action research and evidence gathering activities were also included within wider capacity building interventions (21% of all successful applications, involving either scoping activities, audits or research with academics). Scoping activities were the most common, mainly as a standalone research activity. These were varied in terms of both methodologies and focus, including participatory surveys to identify the number, type and causes of incidents of domestic abuse and sexual violence in pilot communities.

Just under a quarter (24%) of applications involved onward funding, and 60% of these solely delivered onward funding (while the remainder combined onward funding with service delivery). Examples of applications only undertaking onward grants included those providing grants to specialist Black and minority women’s organisations to support their frontline work to end VAWG, and to improve the lives of disadvantaged and under-represented women and girls in deprived areas across Northern Ireland.

Applications combining onward grants with other intervention categories did so in a variety of ways, most commonly with education, training and capacity building (in nine out of 13 cases), for example:

-

combining a range of grants (for example, seed funding, small and larger grants) to support the sustainability of women’s groups in local communities with capacity building and establishing a Centre of Excellence to bring together learning and best practice through workshops and training

-

providing grants of between £10,000 and £50,000 to fund gender-specific peer support initiatives (for example, supporting disadvantaged women living with/at risk of developing mental health problems) combined with learning events, tools, resources and onward grantee training

Support services and frontline service delivery interventions were also delivered with onward grants (in four out of 13 cases). An example was assertive outreach and access to accommodation to support sex workers, women experiencing homelessness and victims of domestic abuse into safe spaces.

Around 22% of successful applications included education interventions. These were discreet and time-limited education and training programmes directly targeting women and girls within communities. Specific audiences were varied and included women offenders and those at risk of reoffending, refugee women, young women and girls (aged 9–15) from areas of high deprivation, homeless victims of modern slavery and older women (aged over 55) in a specific local authority area.

Reflecting these diverse audiences, the subjects of education interventions were also varied. Topics included training women in the criminal justice system in life skills, emotional wellbeing, healthy relationships and parenting; and using sport and physical activity to support personal development, confidence and empowerment around relationships and sexual health among disengaged girls or girls at risk of exclusion in areas of high deprivation. Specific examples included providing employment support to women from ethnic minority backgrounds who were unemployed and who had limited English language and basic skills.

Training interventions were included in 15% of successful applications. These targeted professional staff, volunteers and/or people with lived experience working for organisations to better equip them to support women and girls. They mainly targeted staff of VAWG centres or services. Specific examples included briefing and information events for senior managers during the rollout of an accredited domestic violence prevention programme; a mentoring process, safeguarding procedures, risk assessments and confidentiality for young female peer mentors; and recruiting and training specialist call handlers to better deal with the complexity of honour-based abuse and forced marriage cases.

The provision of resources, equipment and technology was included in 14% of applications, and included:

-

the provision of clothing and equipment to single pregnant women and young mothers in West London to prepare for the arrival of their baby and/or move into independent living

-

the production of new and modern programme materials for 30,000 Girlguiding units, supporting leaders to reduce time spent on planning and to increase time spent with young members

-

the production of best practice guidance and training materials for midwives to support pregnant women and new mothers in prisons and the community

Technology interventions included the development of new apps and technology and involving delivery or improvement (including the extension of app content and features). New apps included a digital miscarriage risk calculator for women experiencing two or more miscarriages, and the development of existing apps and technology, including updating an existing app with new content to support women through their maternity journey.

Signposting and awareness raising interventions featured in the fewest successful applications (12%), and included:

-

signposting services that provide advice and support to victims of online abuse, including intimate image abuse, with targets to reach almost 950,000 women and girls

-

linking local domestic abuse services directly with project ambassadors (local residents) to help ensure more survivors are signposted to the right support as soon as they disclose

-

providing advice, practical support and signposting for housing, benefit and immigration issues

2.3.4 Monitoring and evaluation plans

The vast majority of applications included plans for some form and combination of internal monitoring activity, internal evaluation and/or external evaluation. Almost 93% of applications included plans to collect monitoring data, primarily regarding activities and outputs but sometimes also outcomes and/or impacts. There was a wide variety of data types within monitoring plans, but common types were quantitative data (such as numbers of grants, activities, outputs and beneficiaries), demographic data (beneficiary age, ethnicity and language) and qualitative data. The collection of qualitative data was mentioned in around 35% of applications, although qualitative indicators were generally not clearly defined and commonly referred to ‘softer’ outcomes such as confidence, self-esteem, wellbeing, happiness and emotional state.

Fund recipients were required to submit basic monitoring data on activities, outputs (i.e. people helped; training delivered; onward funds awarded; etc.) and outcomes as part of grant requirements, as well as monitoring their expenditure against forecasts and budget. Otherwise, there were no standardised approaches by which project monitoring was undertaken.

Just over 93% of successful applications included plans for some form of internal or external evaluation of their TTF activities. However, while some made clear distinctions between the monitoring and evaluation activities proposed, most were less clear. Around 45% proposed to evaluate their activities internally, 14% proposed to evaluate them externally, and 32% reported a combination of internal and external evaluation.

2.3.5 Planned outcomes and impact

TTF did not have a logic model at its commencement with a set of specific intended project outcomes and impacts that funded projects would contribute to and achieve. Funding proposals, and the 137 successful applications within them, aimed to address a variety of issues in a wide range of ways. The intended project outcomes and impacts identified in the review of applications reflected this, and differed widely based on individual mandates, missions and types of organisations applying. These were categorised within a TTF logic model developed for the evaluation as a set of broad possible project outcomes (both short-term and long-term) and impacts at different levels: sector, organisation and individual.

Table 4: Percentage of intended short-term outcomes

| Planned short-term outcomes | Percentage of applications |

|---|---|

| Improved access to quality support for women and girls in need | 81% |

| Improved ability/skill to support women in need | 74% |

| Improved access to resources, guidance and shared learning | 67% |

| Improved sector partnerships and organisational linking | 58% |

Table 5: Percentage of intended long-term outcomes

| Intended long-term outcomes | Percentage of applications |

|---|---|

| Improved physical and mental health management | 70% |

| Improved confidence | 51% |

| Increased help-seeking | 49% |

| Improved sector knowledge and increased assets | 46% |

Table 6: Percentage of intended impacts

| Intended impacts | Percentage of applications |

|---|---|

| Reduced risk and/or experience of violence and harm | 55% |

| Women and girls able to act as own agents | 54% |

| Sector shift from response to prevention | 41% |

Most successful applications included multiple intended short-term and long-term outcomes and impacts.

2.4 Reported outcomes and impact

This section explores the self-reported outcomes provided by the TTF projects in End of Grant reports. This data is mixed in terms of coverage and the amount, type and quality of data provided varies considerably. Those funded in the 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 funding rounds could not provide any outcome or impact data as their projects were ongoing. Combined, these factors limited the analysis to projects providing sufficient data of good quality within the 119 projects providing End of Grant reports at the time of fieldwork.

Most applications included a combination of multiple short-term outcomes, with fewer applications detailing long-term outcomes and/or impacts. This is reflected in the self-reported data, as most organisations provided data on multiple short-term outcomes, and fewer provided data on long-term outcomes and impacts. Projects in the most recent funding round (2021/2022) had not submitted End of Grant reports at the time of research. Therefore, the full extent of outcomes may not have been realised yet.

2.4.1 Short-term outcomes

Of the 119 projects that provided data on outcomes and impacts through their End of Grant reports, 44% provided some form of evidence showing improved access to quality support for women and girls in need, the most common short-term outcome included in applications (Table 4). Evidence focused both on increasing the number of women and girls able to access support, but also included the quality dimension of this outcome. Examples included an organisation implementing a project to support women and girls at risk of violence, which reported that 95% of clients felt they had gained access to social networks and support as a result of the project, enabling them to access services and better support.

Thirty-five percent of projects reported delivering outcomes in terms of improved ability and skill to support women in need. Outcomes reported were primarily related to training delivered and the resulting increase in individual knowledge and skills to support women in need. Some also related to increased organisational capacity and changes in ways of working to better meet needs. For instance, a national organisation tackling homelessness for women survivors of modern-day slavery provided free training for frontline professionals to spot signs of modern slavery and intervene. Of the participants who responded to a feedback survey, 97% reported that the information they had received would enable them to better protect people against the risk of modern slavery.

Thirty-four percent of projects also reported positive outcomes related to improved access to resources, guidance and shared learning. Examples included projects to create a platform for a UK-wide partnership of over 250 members (including not-for profit, sport, education, health, police and local government organisations) to respond more effectively to domestic abuse and sexual abuse. An app was developed to improve access to guidance and resources. This was downloaded by almost 21,000 users, and the directory was expanded to over 450 specialist domestic abuse services.

Improved sector partnerships and organisational linking was the least common short-term outcome found in applications, but the second most reported on by organisations themselves following implementation. Forty-two percent of projects reported evidence of outcomes in this area. Examples ranged from individual meetings between a project team member and a local council (to discuss referral pathways with relevant agencies for young pregnant women at risk or experiencing abuse) to wider and more strategic networking activities across multiple organisations.

Table 7: Reported short-term outcomes

| Reported short-term outcomes | Percentage of projects |

|---|---|

| Improved access to quality support for women and girls in need | 44% |

| Improved sector partnerships and organisational linking | 42% |

| Improved ability and skill to support women in need | 35% |

| Improved access to resources, guidance and shared learning | 34% |

2.4.2 Long-term outcomes

TTF applications included fewer long-term outcomes in proposals, which was reflected in self-reported evidence on long-term impacts. Evidence of long-term outcomes on physical and mental health management was most commonly reported (by 39% of projects), including an onward grantee who explained how the grant enabled them to change how they assessed women and determined and prioritised their needs, leading to positive outcomes for beneficiaries.

Evidence around the improved confidence of women and girls was both quantitative and qualitative, with evidence from 37% of TTF projects demonstrating the results of work towards this outcome. For instance, quantitative evidence from a project providing one-to-one specialist support for women and girls aged over 16 who were affected by abuse showed that, of the women self-reporting in a survey, 61% felt more confident, 53% felt better able to deal with problems, 60% felt better able to make decisions, 51% were clear that the abuse was not their fault, 30% were more confident in their parenting skills and 42% had a better understanding of the impact of abuse on their children.

Evidence of increased help-seeking by women and girls was less common than other outcomes (20% of projects), although there was usually clear quantitative evidence showing increased service use (such as a charity for Muslim women and girls reporting a 25% increase in contacts to its helpline in 2017).

Long-term outcomes in improved sector knowledge and increased assets were found in 31% of projects that reported. All the self-reported evidence related to this outcome showed positive achievements. Examples included an organisation stating that 98% of professionals attending their courses had increased their knowledge of the impact of period poverty among young people.

Table 8: Reported long-term outcomes

| Reported long-term outcomes | Percentage of projects |

|---|---|

| Physical and mental health management | 39% |

| Improved confidence of women and girls | 37% |

| Increased help-seeking by women and girls | 20% |

| Improved sector knowledge and increased assets | 31% |

2.4.3 Impacts

A variety of evidence of contributions towards changes in the risk and/or experience of violence and harm for women and girls was reported in 21% of projects. In some, this was anecdotal evidence regarding individual beneficiaries; for example, a small project supporting women who were being forced through the family law courts process by an abusive ex-partner explained how one client left court with the protection she needed after a team member intervened acting as a McKenzie friend. In a second example, a project reported that 93% of the women it supported in accessing advice, emotional and practical support felt their risk had reduced compared to before the project.

Evidence of contributions towards women and girls acting as their own agents was both quantitative and qualitative, and 26% of projects showed evidence of this impact. For example, a charity supporting women from ethnic minority backgrounds reported quotes from women it had supported, including: “I can access the doctor’s surgery better. I know what to say on the phone. I am able to go out and know how to use services like asking for a prescription at the doctors.”

Evidence regarding contributions towards a sector shift from response to prevention was found in 21% of projects. One example came from the final report of an external evaluation of the Good for Girls Project, which aimed to increase access for young women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds to holistic early intervention mental health support. The report stated that:

BAME young women can access relevant, holistic early intervention mental health support in trusted community spaces. This includes support and guidance from trained youth professionals, and opportunities to develop relationships, skills and tools to maintain positive mental health. Young women get support earlier, meaning fewer require referral to specialist services.

A second project supporting women from ethnic minority backgrounds who were survivors of violence and domestic abuse reported that women using their services were leaving violent and abusive situations at earlier stages.

Table 9: Reported impacts

| Reported impacts | Percentage of projects |

|---|---|

| Reduced risk and/or experience of violence and harm for women and girls | 21% |

| Women and girls being able to act as their own agents | 25% |

| Sector shift from response to prevention | 21% |

2.5 Lessons learned by delivery teams

Organisations (and sometimes beneficiaries) identified a range of lessons related to both TTF and individual project processes. These were drawn from their experiences of implementing TTF funded projects (or receiving their services); some were project-specific, while others applied more broadly. While there were no clear links between lessons and specific intervention categories or delivery models, several lessons relating to onward funding were identified. Key lessons identified by delivery teams relevant at the Fund level included the following.

-

onward funding programmes require sufficient time (over two years) and organisational inputs to establish and implement grants processes, deliver grants and wind down

-

a ‘test-and-learn’, learning-focused approach to grant-making and grant management improved project outcomes and provided additional outcomes for onward grantee organisations

-

working as part of a national (or multi-area) partnership provided smaller organisations with opportunities to build capacity, learn from others and develop more effective working practices

Project delivery teams identified lessons for project design, implementation and outcomes of relevance to future schemes that are relevant to consider in future project design, including the following.

-

adapting implementation to account for different (and changing) contexts and requirements of specific target communities benefited women’s participation and project outcomes

-

project design should consider all stakeholders’ capacity, interests and relationships – especially if not directly involved in implementation, but able to influence project success

-

there was significant value in including women with lived experience in delivery (for example, in providing support to specific groups of women), and particularly on advisory/steering groups

-

engaging with some female stakeholder groups (for example, carers, refugees, etc.) relied on local partnerships and direct contact, and could be more difficult and costly than other groups

A wide range of issue-specific or project-specific lessons were also identified by delivery teams, including the following:

-

working with women and girls with multiple and complex needs required time to establish trust between project staff and their peers, and creative approaches to reach beneficiaries

-

remote training on sensitive issues increased risks around providing the training content and dealing with potential emotional impacts on trainees

-

online portals/tools, however, provided safe ways for women and girls to raise sensitive issues or approach projects providing support and were better than phone helplines

Some organisations identified a set of clear issues and recommendations to help inform wider policy on particular issues, highlighting the need for wider engagement with local frontline organisations to understand their experiences, knowledge and expertise.

2.6 Plans for future funding

Half of the direct grantees implementing projects provided details of their future intentions and plans post-TTF funding. In most cases, these were positive, with intentions to continue improving and/or expanding services using experience and capacity developed during their TTF project. In most cases, this included a continuation (or increase) in income from other sources developed during the TTF project, increased networks and/or learning to broaden services provided or areas covered. For example, one organisation intended to expand its services from local to regional (with local authority funding in place in each area) via a regional model to test delivery across a wider area. In others, future funding was still being sought but plans were positive, and several large funding applications had been submitted or fundraising groups established. Some had also used part of their total grant as ‘sustainability funding’, as follows.

A £1.2 million project to update a pre-existing app with new content (including specific content for women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds) to support women through their maternity journey and improve maternity outcomes received sustainability funding of £75,088 to increase the capacity to train and grow their engagement team and to ensure that the business-wide operational activity had the capacity to train, support and embed new project staff and processes into the charity.

A £600,000 project to extend rape crisis trauma-informed frontline services to specific women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds and women with disabilities received sustainability funding of £10,000 to invest in improving their IT processes, specifically to allow each delivery partner to implement a secure multi-language web form on their websites to enable first language survivors to make referrals at a time convenient to them through the portal.

A £2.3 million project providing match funding grants to women and girls charities received sustainability funding of £10,000 towards building digital fundraising skills, leadership training for women staff members and establishing a philanthropic community specifically targeting causes that help women and girls.

Around a fifth of the organisations describing future plans were less positive, with funding applications that were uncertain or not yet secured. In some cases, services had continued using internal funds (at least in the short term) while alternative funding continued to be sought. In a few cases, project work and services had to stop. COVID-19 also had an impact on this, with funding streams shifting focus or service requirements and delivery models also changing.

Appendix 3: Findings from case study research

3.1 Introduction

This appendix summarises the key process findings emerging from the experiences of eight bid area case studies across past and present funding rounds. Research was conducted by Kantar Public in November and December 2022. The methodological approach will be discussed first, followed by a synthesis of overall case study findings and, last, the individual case studies.

3.2 Methodology

Kantar Public conducted 22 in-depth interviews across eight organisations, with each interview lasting between 45 and 60 minutes. Between one and five people were interviewed in each case study, with interviews lasting between 60 and 90 minutes. Interviews were conducted via Zoom or telephone. The case study research aimed to explore the detail of TTF funded projects’ rationale for their bid and bid design, experience of delivering their project and lessons learned, and perceived outcomes/impacts.

3.2.1 Case study selection

Case studies were selected based on agreed criteria with DCMS, ensuring a spread across:

-

year funding was received

-

total cost of the funded project

-

location of the project

-

project focus

-

intervention type

-

number of relevant people available for interview within the organisation

-

delivery model (as per the logic model)

The composition of the eight case studies selected is illustrated in Table 10 below. All cases are direct grantees, with some involved in onward grant-making.

Table 10: Overview of case studies

| Year funding received | Four projects funded in 2021/2022, one funded in 2020/2021, two funded in 2017/2018 and one funded in 2016/2017 |

|---|---|

| Total cost of the funded project | Two projects received £150,000 to £299,000, three received £300,000 to £699,000, one received £700,000 to £999,000 and two received £1 million to £2 million |

| Location of the project | Four projects based in England only; two in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland; one in England, Scotland and Wales; and one in Wales only |

| Project focus | Improving literacy rates among deprived populations Development of a digital tool to support those experiencing online abuse A sports-based ‘big sister’ programme Onward funding and targeted support (two projects) Genetic screening pilot to detect ovarian cancer Frontline services to women from ethnic minority backgrounds who have experienced violence and have no recourse to public funds (NRPF) Development of an advocacy model to improve current practice relating to financial control as a form of domestic violence |

| Intervention type | One project delivered an education intervention, including elements of training One project delivered an app (resources, equipment and technology intervention) Three projects delivered, or had elements of, onward funding Two projects delivered action research/awareness raising (capacity building) Two projects delivered, or had elements of, frontline services |

| Delivery model | Two projects = model 1 (delivery of activity accessed directly by beneficiaries) Two projects = model 2 (delivery of intermediary capacity building interventions that subsequently support the final beneficiaries) Four projects = model 4 (onward grants are used to deliver intermediary capacity building interventions that subsequently support beneficiaries) |

3.2.2 Recruitment

Kantar Public spoke to stakeholders with a strategic remit (for example, those involved in the design and oversight of TTF projects) and stakeholders with an operational remit (for example, those involved in day-to-day delivery of TTF projects). The sample was snowballed from a primary contact of each project, shared by DCMS. A pre-identified scope of interventions and areas of enquiry were agreed for each case study. Each case study involved an initial document review of the bid application documents, which included details on interventions, funding round project focus and delivery model. Interviewers identified the project theme, year of delivery, intervention types being delivered, whether projects were involved in multiple rounds of funding and the reasons for case study selection.

3.3 Case study analysis: Synthesis of findings

This section outlines the key findings of the case study research, first reporting perceptions and experiences of the bid design and delivery stages, then exploring the common facilitators and barriers to delivering the funded projects, and finally considering the sustainability of the projects beyond TTF funding.

3.3.1 Bid design and application experiences

Grantees receiving funding in earlier rounds found the bid application a simple and straightforward process, especially in earlier years of the Fund. Of the eight case studies presented, three were past grantees, one of which no longer had employees in the organisation involved in the bidding process and so could not comment on their experiences. Two other past grantees were also involved in the most recent round, and mentioned that the previous rounds (2016/2017 and 2017/2018) had been less time-consuming and more straightforward due to less information being required. However, one case study mentioned that the lack of guidance and support in the 2016/2017 round had been a challenge.

Case studies who took part in the most recent round of funding found the application to be more repetitive and unnecessarily time-consuming. Stakeholders felt the bid application process could have been more streamlined and that the information required of them was repeated across the application form. For example, one case study mentioned having to break down outcomes by quarter, before having to repeat this information again in the quarterly outputs. It was felt to be an onerous process, requiring large resources. Another case study felt the outputs section of the bid application form was the most complicated, as it asked for a lot of very specific details:

It would almost be impossible for a smaller charity to do what we did, and we only did it by pulling almost all our resource into it … it was a real gamble. If it hadn’t have paid off, we would have wasted a lot of time and money on.

– Case study interview participant

Learnings from previous rounds were generally felt to facilitate a smoother bid application process. When case studies were involved in the bid design and application in prior rounds, they felt it helped them complete the application successfully in subsequent rounds. Some case studies felt they had become more efficient in the application process due to being more familiar with the documentation and requirements. For example, one case study knew how long it would take them to compile information for the application and also knew how to differentiate between outputs and outcomes based on their previous experience. Another case study attributed their success in the most recent round to having had more time to build an evidence base illustrating the need for the intervention. It is important to note that one case study felt being involved in multiple rounds had not helped them, as the content needed was so different each time. In some cases, grantees reported that learnings from previous rounds had enabled them to cater their project plans to the TTF funding criteria:

We’ve got pretty good at being able to match something that we want to get funded, with what the criteria is for funding provision.

– Case study interview participant

Guidance and support from DCMS was helpful in mitigating a demanding bid application process. Case studies felt DCMS was supportive throughout the six-week bid application process and that the guidance it provided was clear and constructive. This helped reduce the complexities and facilitate a smoother process. This was only mentioned by grantees who bid in the most recent round of funding, suggesting that, although the most recent application process was felt to be more complex, it was somewhat mitigated by support from DCMS.

3.3.2 Delivery experience

Overall, case studies were positive about their experience of delivering TTF projects and felt they were able to achieve, or were on track to achieve, their goals despite some challenges.

Effective partnership working facilitated the successful delivery of projects. Across case studies, interviewees reported the importance of partnering with other organisations for the successful implementation of interventions. This was common across grantees irrespective of the interventions they implemented. Case studies often spoke highly of their delivery partners and of the positive relationships formed with them. These collaborations, along with the expertise derived from them, were felt to be instrumental in overcoming barriers and delivering successfully. Stakeholders also mentioned that the knowledge and learning they had gained through working with delivery partners was an unexpected positive outcome of project delivery:

So far, it’s been around our working patterns with external partners … It’s nice to feel that we’re one team, rather than external development, and that’s reciprocated.

– Case study interview participant

Scoping research in the early phases of delivery was important for informing the direction and development of overall interventions. In some cases, grantees conducted scoping exercise after receiving funding, where they conducted research with target beneficiaries. These early research activities shaped the direction and development of interventions. For example, one case study held workshops with practitioners and survivors of abuse to test the usability of a new digital tool, which helped to identify priority areas for improving the function of the tool.

Case studies that did onward funding felt their ability to prioritise women and girls from minority backgrounds in their projects was a success. With TTF funding, some grantees were able to ensure a proportion of onward grantees worked with women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds and marginalised communities. One case study mentioned that this was not achievable in the past with regular government funding, so being able to incorporate it in their TTF project was an important success.

Consulting beneficiaries and advisors at various stages of delivery allowed direct grantees to develop and adapt their interventions more effectively. Some grantees carried out consultations, feedback sessions and evaluations at various different points of the design stage or delivery, which informed the development or adaption of their interventions. For example, one case study introduced an SMS option for students to provide feedback on a training programme, leading to an increase in responses. Interviewees from another case study, consulted women who were using their service on the design of their interventions (training programmes and a refuge centre) during the design phase, felt this consultation contributed to buy-in from beneficiaries at later stages of delivery.

Timeframes for project delivery were challenging. Case studies felt the turnaround times were tight for delivering interventions, particularly among those engaging in onward funding, as government funds are required to operate and deliver funds on an annual basis. Delivery times granted to projects varied between funding rounds; projects had between 12 and 36 months to deliver their interventions. Direct grantees often needed to complete numerous administrative tasks to set up their onward grant structures, including their own bid selection processes and fund management. Incorporating this into the delivery timeframes could result in knock-on effects for onward grantees, as they had less time to deliver their funded projects.

Challenges recruiting suitable individuals for project roles hindered delivery. Case studies mentioned that filling specific job roles for projects was sometimes an issue. Grantees felt this was due to various factors, including the short-term nature of the roles and contextual factors such as a general skills shortage within an often low-paid and stressful sector. Recruitment issues often caused timelines to slip, which then had a knock-on effect for the length of job posts:

It’s a difficult sector – it’s high stress, dealing with trauma and crisis, so people often burn out.

– Case study interview participant

3.4 Outcomes and impacts

Overall, due to the nature of the projects and the aims they are trying to achieve, measuring outcomes and impacts was challenging and outcomes and impacts were often based on anecdotal evidence. Furthermore, for those case studies in the most recent round of funding, many felt it was too early to comment on outcomes or impacts at the time of fieldwork, as project delivery was ongoing. The common outcomes and impacts across the case studies are discussed in this section.

3.4.1 Women and girls supported by TTF funded services

Overall, case studies felt that women and girls had been supported by the services provided, evidenced by direct feedback from beneficiaries and monitoring data. In one case study, reports provided evidence that marginalised women had improved their mental health along with their financial resilience. In another case study, the project helped provide safe accommodation and training for survivors of abuse, which some of the women stated had helped save their lives.

3.4.2 Increased awareness of women and girls’ issues

Case studies spoke about how activities undertaken for TTF projects had helped raise awareness among the general public and the wider public sector about the issues women and girls face. For example, one case study felt there had been a significant increase in the awareness of economic abuse among policy makers, domestic abuse charities and financial organisations. In another case study, outreach activities were felt to have led to increased awareness of the genetic risk for ovarian cancer among government bodies, as well as among the general public:

It’s hugely raised awareness, and created momentum, not just in the women’s domestic abuse sector, but in loads of related sectors, such as the financial services sector, which is increasingly recognising economic abuse as a form of vulnerability to their customers.

– Case study participant

3.4.3 Contribution to policy and process developments

In a few cases, TTF projects were felt to have contributed to wider policy developments. For example, one case study felt that their research had contributed evidence that culminated in significant policy changes, such as the recognition of economic abuse in the Domestic Abuse Act and the inclusion of economic abuse in the Financial Conduct Authority’s Code of Conduct. Another case study’s campaign work on the genetic risks of ovarian cancer was felt to have contributed to an improved process for diagnosing patients, implemented by the Department of Health and Social Care.

3.4.4 Increased profile of TTF funded organisations

Some grantees felt that the profile and awareness of their organisation’s work had increased as a result of their TTF funded project, which had unexpected positive outcomes. In one case, staff spent less time on their regular outreach activities as they experienced increased interest in, and attendance at, their programmes due to the increased profile of their organisation.

3.4.5 New relationships formed as a result of TTF

Some cases noted that the new relationships formed with individuals and organisations through their project would be likely to open up opportunities for future work. One case study mentioned they had formed new relationships with nurses and physiotherapists, which would benefit the organisation in the longer term. Another mentioned that the positive relationships formed with their partners meant future collaborative bids were likely:

We have a much closer working relationship with [organisation], and that has been a really positive thing for us.

– Case study interview participant

3.5 Sustainability

Overall, the continuation of the most recent and of past grantees’ projects depended on their ability to secure funding. At the time of research, the grantees of the most recent funding round were in the process of seeking future funding to continue or develop interventions and reported significant uncertainty in the future of their projects. However, a project engaged in onward funding in the most recent round (2021/2022) noted that two of their onward grantees had already secured future funding. In other projects, onward grantees were yet to secure future funding.”As a result of Tampon Tax ending, there will be a significant drop in funding in the sector.” (Case study interview participant)

Some past grantees secured funding from other sources, which allowed the continuation of elements of their projects. This funding came from a range of sources, including internal streams of income, additional funding from external partners or government funds (for example, Home Office funding). Where projects accessed further funding, some activities continued. One project was able to keep their refuge for women open at reduced capacity, and a second was able to adapt and expand their pilot training programme to organisations in Northern Ireland and Scotland.

3.6 Case study summaries

3.6.1 Case Study One (TTF 2017/2018 funding round)

Case Study One (CS1) is an organisation that specialises in providing frontline holistic support to women, children and young people from ethnic minority backgrounds in the North East of England, with a particular focus on women with NRPF. With the funding, the organisation opened a refuge specifically for women with NRPF and also extended their education, training and holistic support services. Overall, CS1 felt the funding was instrumental in their ability to meet the needs of their beneficiaries and have subsequently opened other refuge centres with other funding.

Bid design and application experience

Staff involved in the bid design and application process no longer work at CS1. Those interviewed as part of the case study worked in operational roles across CS1’s outreach and advocacy services and could not comment on the application experience.

However, existing staff were involved in activities that had informed the bid design. For example, CS1 carried out a consultation with existing beneficiaries that highlighted the need for a refuge and directly informed the TTF application:

It was a great opportunity to be part of that and get the service users to be part of that as well.

One of the things I was really happy about was the involvement and the voice of the women as well.

Delivery experience and progress

Overall, delivery of the funded project was felt to have gone very well. CS1 felt that there were very few barriers to delivery and that they achieved their ultimate aims of creating safe spaces for women from ethnic minority backgrounds with NRPF and supporting them with a range of activities, including access to social services, immigration and legal help, and personal development and life skills.

Frontline services

Setting up the refuge was a relatively straightforward process. CS1 utilised their existing networks to find a suitable location close to the CS1 and secured a property without difficulty.

In 2017 we opened one refuge and then because of high demand of No Recourse to Public Funds we wanted another … when we got the tampon tax funding, then we opened another refuge specialised for NRPF women.

Education and training

CS1 provides a range of education and training opportunities to women, including English language courses, employability support, life skills and social integration activities. This is an ongoing core element of CS1’s services supported by TTF funding and accessed by beneficiaries of the refuge.

Successes and facilitators of delivery

Utilising existing relationships to secure a property for the refuge meant that this was a relatively straightforward process:

We knew a guy who had a property near us … so we negotiated with him.

As a result of consulting women during the bid design phase, CS1 achieved buy-in from the beneficiaries and found them to be excited and enthusiastic about the refuge.

Challenges and barriers of delivery

CS1 needed to recruit extra staff to support the project. CS1 felt that getting the ‘right’ frontline staff in was a challenge as it was hard to get people who understood the project’s aims and objectives and the level of trauma experienced by the beneficiaries, as well as how to conscientiously navigate this in their interactions with beneficiaries.

Outcomes and impact

Overall, 26 women and nine children were provided with emergency accommodation over one year. A further 36 women participated in a range of training courses, of which 15 women completed accredited women’s champions training. Under 5% of women who accessed services returned to abusive families; 95% continue to live independently and free from abuse.

The funded project was felt to have had a profound impact on the lives of beneficiaries, as well as a significant impact on the organisation as whole. Staff felt that the refuge had achieved its aims of providing safe accommodation and training for survivors of violence and abuse who had NRPF:

Some of them [the women] say the project saves their life.

One of the women said … when I first got involved, all I could see was darkness ahead of me, but I now I can see a light at the end of the tunnel. Just to even hear that … I think that made a lot of difference for us.

The project was also felt to have had an unexpected organisational impact, raising the profile of CS1 in the VAWG sector and enabling the organisation to reach more beneficiaries. Staff did not need to spend as much time on their regular outreach activities such as door-to-door leafleting or other advertising, and felt this was due to word of mouth about the project. CS1 felt that TTF funding helped the organisation gain momentum, and they have since opened three other refuges.

Looking ahead

CS1 have continued to run the refuge since TTF funding ended in 2021. CS1 plan to keep the refuge open with other sources of funding (for example, Home Office funding) but have had to introduce cutbacks, including reducing the number of bedrooms in the refuge, reducing or removing elements of the training and support on offer to women, and introducing further limits on the number of beneficiaries they can accept:

It’s a sad thing.

Three years ago we were proud of ourselves … but now we have to say no.

3.6.2 Case Study Two (TTF 2021/2022 funding round)

Case Study Two (CS2) is a national charity working with disadvantaged children. Their programme is a 10-week education programme for girls aged 11–14 who have been excluded, or are at risk of exclusion, based in alternative education settings such as Pupil Referral Units (PRUs). The project aims to increase girls’ literacy/oracy and communications skills, increase their confidence and support positive relationships through the exploration of literary texts.

Bid design and application experience

CS2 had applied for TTF funding rounds multiple times but had previously been unsuccessful. They attribute their successes in the 2021/2022 funding round to the strengthened evidence base they had built to demonstrate the need for the programme. CS2 were surprised and pleased to see sustainability as a specific element of the bidding process and appreciated the flexibility of the Fund, which allowed them to adapt the programme to best meet the needs of their target group:

We’ve flexed to support [students’] needs in the best way possible, and the funder has supported us to do that. And I think that’s the mark of a really good funder … we’re all staying on the same hymn sheet.

Delivery experience and progress

At the time of the case study research, CS2 was at the mid-point of delivery, with delivery on track within the planned timeline and budget. There had been some variation in the delivery plan since the bid was designed, for example a shift in focus away from sports-based role models and the reallocation of resources to reach additional schools.

Intervention: training and education

The project was delivered by a specially recruited project manager, researchers and trainers at CS2. Schools are recruited to participate, and teachers receive bespoke training to deliver the 10-week programme. Students are provided with resource packs as part of the programme, including a workbook and literary texts, which they are able to keep after the programme ends:

The idea is that, by the end, [students] should feel more confident in representing their own voice.

Successes and facilitators of delivery

A key success of intervention delivery to date includes the successful recruitment of schools, exceeding CS2’s original target to work with 1,500 girls in over 300 educational settings in the first terms and a further 192 in the second and third terms:

[The materials] makes the group feel really special… the teacher can come in and say this is all for you, just for you, no one is else taking it away … it’s all about giving attention to those young people and making them feel included.

The key enablers to delivery have included designing a programme that meets a clear need and gap and iteratively adapting the programme plan and educational materials in line with feedback. Establishing an advisory group who have supported with the review of programme materials has also enabled effective delivery:

Everything has been about getting better and better at supporting the young people, engaging them better and giving them more of what they need and what they want.

Challenges and barriers of delivery