Sacred violence: the enduring role of ideology in terrorism and radicalisation (accessible version)

Published 20 March 2025

Dr Donald Holbrook

This report has been independently commissioned. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the UK Government or the Commission for Countering Extremism.

Acknowledgments

While all the views and opinions contained in this report are the author’s, he wishes to recognise all the support and assistance provided by UK Counter Terrorism Policing in conducting this research.

Foreword by Robin Simcox, Commissioner for Countering Extremism

An act of terrorism is an act of unforgivable cruelty. It irreparably devastates the lives of innocent people. While the threat remains unrelenting, we should never come to simply accept terrorism as a facet of modernity. It should always shock the conscience of a healthy society.

In one way, understanding why acts of terrorism occur is very simple. Terrorists are often explicit in detailing why they act the way they do and what motivates them.

Time and again, these explanations are ideological. Yet despite this, the centrality of ideology to explaining the actions of terrorists and extremists remains disputed by some. Terrorists’ stated motivations for their actions are dismissed as not empirically verifiable or tested.

Emphasis is instead placed on more material factors – like economics – or psychological factors and mental health.

This study by Dr Donald Holbrook puts ideology back at the heart of the debate. He analyses 6,000 individual pieces of “mindset material” possessed by 100 convicted terrorists in the UK. It gives him an unparalleled insight into what was driving these offenders.

Dr Holbrook finds that ideology is “indispensable in understanding terrorists’ patterns of contention: why they fight, what they hope to achieve and what is permissible in their struggle.” Immersion in the nuances of ideology will differ depending on the individual. But it is always there.

That is because ideology fulfils an irreplaceable function. It creates a framework for how to behave and what to think. It then outlines the rewards, spiritual or otherwise, for doing so.

That can include justifying acts of terrible violence. We have seen the consequences of that all over the world – including here in the UK – time and again in recent decades.

A terrorist’s mobilisation can be influenced by a multitude of personal factors. Sometimes it may be a grievance tied to foreign policy or demographic change. It could even just be the publication of a cartoon. Yet it is the ideology that imbues grievance with political significance and determines who will suffer the violent consequences.

Terrorists’ grievances can ultimately never be sated because they are laced with ideological demands. Any government that tries to do so will find themselves making unacceptable concessions that would fundamentally change the character of our country.

Ultimately, it is ideology which validates and directs violence. It is ideology that guides behaviour. It is ideology that provides the framework for why terrorists think the way they do. In short – and as Holbrook’s study definitively proves – ideology matters. Combatting it must be central to government’s response to terrorism and extremism.

Robin Simcox, Commissioner for Countering Extremism March 2025

Executive summary

i. Successive official reviews into counterterrorism and counterextremism in the UK have recognised that ideology is central, both to individuals transitioning to terrorism and the toxic and permissive environment that encourages and glorifies such acts. But what does this ideology consist of, and how do we define it? What type of ideological content do terrorists favour and consume? What is the nature of this material and where does it come from? The purpose of this report is to address these questions by providing a conceptual and empirical guide to the way in which ideology has featured in transitions to terrorism in the UK.

ii. The conceptual discussion notes that the presence and role of ideology in terrorism remains contested in academic research and debate. This debate, moreover, does not offer a universally accepted definition of ideology in this context. Large sections of the academic community have regarded ideology as insignificant in pathways leading to terrorism. Their objections can be divided into two broad and related categories: causal (ideology is unrelated to action) and cognitive (terrorists do not absorb or understand ‘their’ ideology).

iii. Such accounts offer important caveats, but fail to recognise how ideology separates terrorism from other violent crime and places it on a continuum of other types of political violence. They also neglect to offer definitions of ideology that reflect wider and more commonly held views among scholars of ideology. The latter present ideology as: a system of belief with shared values, understanding and purpose that guide the collective action of those bound by these beliefs.

iv. Accordingly, ideology becomes indispensable in understanding terrorists’ patterns of contention: why they fight, what they hope to achieve and what is permissible in their struggle. It also helps us understand how terrorist leaders and those with influence over extremist movements seek to mobilise their constituents with messages of shared grievance, calls for united action, and promises of collective rewards and objectives.

v. The conceptual section concludes by arguing that ideology is an indispensable component of terrorist motivation, but exists on a spectrum from limited to substantial levels of engagement, while it coexists with, complements and contextualises other factors leading to terrorism.

vi. The empirical section concentrates on ideological content and media collected by terrorists, that can be seen as representing the particular pieces of a broader ideological community to which an individual is drawn. It does so by offering a unique analysis of such material collected by 100 convicted terrorists in the UK, arrested between 2004 and 2021.

vii. It examines their 6,000 individual items of ideological material, dividing the analysis into three stages: (1) broad trends identified across the dataset, (2) the most popular types of ideological content, titles, themes, and commentators, and (3) patterns of consumption of ideological material, with some thoughts offered regarding its function in the wider context. Finally, the section presents a classification system to categorise these publications according to their substance to illustrate the type of messaging that this material conveys.

viii. The report finds that the consistent presence and volume of ideological material points to the importance of both ideology for terrorists more generally and in transitions towards involvement in such violence. Meanwhile, it finds that convicted terrorists did not fixate on extreme ideological material – content that condoned violence – but rather displayed broader ideological interests.

ix. The focus of extremist ideological material is on building a narrative whereby lethal violence is seen as proportionate, moral and obligatory in defence of an identified community. Four themes stand out: revivalism, salvation, community preservation and sacred violence.

x. These themes help us to discern the function of ideology for these subjects: to instil a sense of community that needs protecting from hostile outsiders, to justify extreme measures as proportionate in its defence, and to lay out the objectives of that community and the rewards individuals may enjoy if they contribute towards those objectives.

xi. In terms of consumption, the convicted terrorists in this sample were found to be selective and discerning in their engagement with ideological material. They engaged with such material directly – through reading, viewing, annotating – and indirectly – casually, or more organically through promotion or adoption of cultural or aesthetic manifestations of their ideological domains, with everything from the construction of their online avatars to their choice of clothing. Consumption was usually a combination of individual and collective engagement, both online and offline.

xii. The observed importance of ideological engagement, relative to other factors that lead to terrorism, however, varied between individuals. We can surmise, moreover, given the duration of ideological engagement for many individuals, that such engagement and interests were not necessarily the trigger or catalyst that prompted individuals to become involved in terrorism, but rather the justificatory context that shaped and channelled that involvement and determined its direction.

xiii. The empirical section emphasises how ideology intertwines with other elements that form part of pathways to terrorism, shapes their direction and instils them with meaning and significance. Ideology does not explain involvement in terrorism in isolation, but the same can be said about any of the other factors that lead to terrorism. These pathways are complex and the combination of factors that lead people to follow them are unique, as they are experienced by individuals, while they can be grouped under more generally identified themes. There are different pieces to the terrorism puzzle and we must observe all of them in combination to understand its emergence. Without ideology, however, the overall picture that the puzzle depicts remains incomplete.

xiv. The report concludes by arguing that terrorism and its permissive environment cannot be understood without reference to ideology. It further argues that counterterrorism and counterextremism policy within the UK and its underpinning practice must, therefore, incorporate an understanding of ideology and its function in transitions to terrorism. It argues that developing and maintaining a sustained understanding of the ideological material consumed by terrorists, as opposed to the material available in the ‘world out there’, is imperative. It suggests that this material constitutes the observable dimensions of the ideological drivers of terrorism, allowing us to explore their interplay with other drivers.

xv. The report further notes that the most visible, impactful and popular elements of this ideological material focus less on facilitative guidelines (such targeting detail or particular tactics or methods of violence), that are more likely to be captured by current terrorism legislation, and more on collective mobilisation and outgroup demonisation.

Background

1. The 2023 Independent Review of Prevent called for a recalibration of priorities to “clarify and emphasise the importance of tackling extremist ideology as a terrorism driver.”[footnote 1] It pointed out that terrorists can only be labelled as such if an ideological motivating factor can be demonstrated, a point echoed by the Crown Prosecution Service.[footnote 2]

2. However, the Review noted that there was a “lack of training on how to manage controversial issues of substance regarding extremist ideology” and that, more broadly:[footnote 3]

Prevent frequently seeks guidance from academics or psychologists with a clinical or theoretical background, many of whom somewhat inevitably tend to focus on psychological factors in the radicalisation process, giving less weight to the role of extremist ideas and worldviews.[footnote 4]

3. The Review found ideology to be insufficiently understood throughout the arc of terrorist involvement.[footnote 5] There was conflicted understanding of the term ‘radicalisation’, while “the strength of the relationship between extremist ideas and violent action” was contested.[footnote 6] For those convicted and imprisoned, the Review expressed concern that the extent to which ideologically driven offenders differed from the wider criminal population was insufficiently recognised.[footnote 7]

4. Moreover, the Independent Review of Prevent cautioned that the role and function of ideology had been a persistent blind spot within the remit of Prevent, noting that the preceding review in 2011 had made similar observations about ideology that still needed to be addressed.[footnote 8]

5. Other evaluations of Britain’s counterterrorism response have reached similar conclusions. The 2014 Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (ISC) Report (relating to the 2013 murder of Fusilier Lee Rigby by two Islamist extremists) found that insufficient attention was placed within the government’s CONTEST counterterrorism strategy on the role of extremist ideology in processes leading towards terrorism.[footnote 9]

6. The ISC’s Report concerning the five terrorist attacks that the United Kingdom suffered in 2017 similarly highlighted the dangers posed by extremist media. The Report cited evidence from Counter Terrorism Policing (CTP) which displayed the volume and scope of such material in UK counterterrorism investigations, noting that the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) maintained a database with 3,000 distinct records of seized terrorist material recovered during its investigations.[footnote 10]

7. Such material that can indicate an individual’s mindset and intent is referred to by CTP as ‘mindset material’. It has been used in almost every terrorist prosecution in England and Wales to evidence intent towards terrorist acts.[footnote 11] However, unless mindset material directly encourages terrorism or is likely to be useful to a person preparing such acts, this material can be legal to possess.[footnote 12]

Definition: Mindset material

CTP designation of media content (books and other written matter, videos, recorded speech or audio) which indicates an individual’s mindset and is used to demonstrate intent during a trial. While this media content includes terrorist propaganda and other extremist ideological content, possessing such material is often only considered illegal if it directly incites violence or is likely to be useful in conducting acts of terrorism.

This mindset material often forms part of wider collections of ideological material that can include moderate content. These wider collections form the focus of this study.

8. At the 2017 London Bridge inquest, Chief Coroner Mark Lucraft QC highlighted the importance of such content in transitions towards terrorism. He suggested that measures prohibiting the possession of content glorifying terrorism should be considered akin to laws prohibiting the possession of child sexual abuse material.[footnote 13]

9. Other studies have also highlighted the risk that extremist material, and the platforms that promote it, can create a climate conducive to terrorism, hate crime and violence. They can also erode the fundamental rights and freedoms of democratic society, without there being any appropriate legislative tools to stem such harmful activities.[footnote 14]

10. As these official reviews and assessments demonstrate, ideology is perceived as central, both to individuals transitioning to terrorism, and the toxic and permissive environment that encourages and glorifies such acts. Yet, its definition and function in this context remain unclear, to the detriment of counterterrorism policy and practice within the UK. The current report aims to address this problem.

Terrorism and ideology

11. The role of ideology in terrorism remains contested in academic research and debate. There is no universally accepted definition or understanding among academics about what ideology means in the context of terrorism and involvement in terrorist activity, although this is not unusual as far as academic research into terrorism is concerned; there is no commonly accepted definition of many of the key terms that relate to terrorism, such as radicalisation, right-wing extremism, lone actor terrorists, or – indeed – the concept of terrorism itself.[footnote 15]

12. It is broadly accepted among academics that terrorism constitutes a type of political violence that is necessarily symbolic in nature, designed to amplify a cause and intimidate governments and populations.[footnote 16] Ideology is also commonly viewed as central to extremist movements, such as Islamist extremist or white supremacist movements, and the terrorist groups and their leaderships that operate within these movements, such as Al-Qaeda or National Action.[footnote 17] However, how individuals are driven by these ideologies and political causes remains contested.[footnote 18]

13. In these debates, there are two main arguments to suggest that ideology is unimportant for individual terrorists:[footnote 19]

- Causal: ideology is not important as a driver to terrorism, or less important than other factors, and

- Cognitive: individuals do not normally absorb or understand the ideology with which they are associated.

14. In terms of the causal elements, academics have pointed out that consumption of ideological content and engagement even with highly extreme ideological material such as terrorist propaganda is, within certain circles such as some online chat forums, relatively common. Many, indeed most, who engage in such activities or display such interests have never made any attempts to ‘mobilise’ towards terrorism or support terrorist activity directly. To give a sense of volume, it was reported that CTP’s Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU) removed around 100,000 pieces of extremist content annually.[footnote 20] Counterterrorism practitioners have also highlighted how common engagement with extremist ideological content has become, particularly online, and how difficult it is to connect such engagement with any intent to act.[footnote 21]

15. Scholars, in turn, have argued that non-ideological factors, especially personal and social factors, weigh more in motivating and triggering individuals to become terrorists, than interest in ideology.[footnote 22] For example, in the case of Vincent Fuller, a white supremacist convicted of attempted murder in Surrey in 2019, the judge assessed that while he had expressed an underlying interest in far-right extremist ideology, there were other significant factors to consider. Fuller appeared to have been triggered by the terrorist attacks in Christchurch, New Zealand, earlier that year, developing a fascination for the attacker. In the day before his attack, moreover, he had been contacted by police for making threats against his partner which fuelled his personal grievance. He had also been heavily intoxicated for the twenty-four hours preceding the attack, which was seen as a further contributing factor.[footnote 23]

16. In relation to cognitive issues, academics have pointed out that terrorists are rarely thinkers or scholars with expertise in the doctrine that is associated with their movement. In fact, their knowledge of these ideological matters sometimes seems to be very limited and they sometimes appear to have engaged with such ideological debates very superficially.[footnote 24] For example, the trial of Darren Osborne, the 2017 Finsbury Park attacker, found that he had been rapidly radicalised over the internet in just four weeks, having been triggered initially by a documentary aired by the BBC.[footnote 25] His knowledge of any deeper ideological arguments appeared very limited.

17. While these are important observations, scholars, the 2023 Prevent Review, CPS guidance and other assessments and clarifications regarding the essence of terrorism have all pointed out that ideology is a necessary component in explaining such acts. Terrorism, according to UK law, is defined as the use or threat of action designed to influence government or intimidate the public for the advancement of a political, religious, racial or ideological cause.[footnote 26] Other jurisdictions have adopted similar definitions.[footnote 27] If ideology, centred around various political, religious, racial or other positions, does not feature in the motivation of individuals seeking to carry out acts of violence and in the way in which that violence is justified and projected, then such acts and individuals cannot be considered terroristic in nature. Scholars and others thus need to reconcile their observations regarding the shortcomings of ideological explanations, as set out above, with the indispensability of ideology as a threshold which distinguishes violence as terrorism in law, as well as scholarly debate.

18. A key element in reconciling these apparently opposing positions is to consider the nature of ideology and define its structure. Surprisingly, much of the criticism and broader debate about ideology in the context of terrorism has left the term undefined.[footnote 28] This has important implications for this debate. For instance, if ideology is defined as rigid doctrine – and by extension, ideological influence is defined as deep and sustained engagement with and knowledge of such doctrine – then the absence of such factors might lead observers to conclude that ideology does not matter for a given identified group of individuals.

19. However, disciplines (such as political philosophy, sociology and cultural anthropology) that have developed expertise into ideology and its essence do not equate it with things like doctrine or theological commentaries. They define ideology as something broader, a prism through which to view the world. Different disciplines agree that ideologies should be seen as maps of shared values, understanding and purpose that guide and shape the collective action of those bound together by these common beliefs.[footnote 29] Scholars have also argued that ideologies rest on three key pillars: diagnosis, prognosis, and a rationale for action.[footnote 30] In other words, ideologies define the shared grievances and aspirations of a community, its proposed methods for reform or change, and the purpose of such action in a desired end-state.

20. Leaders and opinion-makers within political and social movements often reference these three key pillars and they form the core of their mobilising message; the devices are used when they attempt to convince followers and prospective followers to rise up in the interests of the collective objectives and agendas.[footnote 31] Omar Bakri Mohammed, the founder of the radical Islamist network Al-Muhajiroun, even referenced these elements explicitly when describing his group’s recruitment efforts. In a speech to followers, he told them: “when you meet a Muslim or non-Muslim, in your mind [sic] three questions: problem, solution, action.”[footnote 32]

Definition: Ideology

A system of belief with shared values, understanding and purpose that guide the collective action of those bound be these beliefs.

Ideology articulates the grievances and aspirations, methods for reform and change, and purpose, reward and desired end state for those who identify with the system of belief.

21. Therefore, for terrorists, ideology is inextricably social. It provides them with a shared reality and helps solidify their bonds with other likeminded individuals.[footnote 33] Ideology helps us understand how individuals’ personal problems become seen as collective grievances and how individuals may be driven to act through what they regard as prosocial means, in reference to that ideological community. Ideology helps us understand how lethal violence is then justified as a proportionate response to those grievances, and how certain targets are identified and rationalised, including members of the public or certain religious communities like Jews or Muslims. Ideology also helps us understand why individuals might be prepared to suffer or even die in pursuit of their objectives and how such choices can be seen as rational in relation to the rewards individuals believe they will reap as a result. Such rewards could include elevated status, martyrdom, the absolution of sins, or progression towards a desired, collective end-state, such as a religious caliphate or a white supremacist ‘new world order’. In short, ideology is indispensable in understanding terrorists’ patterns of contention: why they fight, what they hope to achieve and what is permissible in their struggle.[footnote 34]

22. Let us now re-examine the two sets of concerns about ideology and terrorism as presented above. With regards to the causal elements, it is true that exposure to and engagement with ideological content condoning terrorism or even terrorist propaganda is relatively common and much more prevalent than instances of terrorist motivation. In other words, far more people consume extreme ideological content than ever seek to become involved in terrorism. But the same can be said, of course, for all the other elements that are identified in relation to radicalisation and mobilisation to terrorism, such as a need to belong or address grievances, prior record of criminality or violence, or a sense of suffering, psychological hardship or mental ill-health. Nothing in the structural drivers, individual incentives and enabling factors that explain transitions to terrorism is unique in isolation. Rather, it is their unique combination for each individual terrorist that explains her or his progression towards such involvement.[footnote 35]

23. Ideology is not in opposition to such factors. Rather, it instils these various components, such as status, belonging, reward, and in-group and out-group definitions with meaning and significance and helps channel personal grievances and crises into something collective, whereby individuals are driven to carry out symbolic violence to influence a government or intimidate the public in order to advance a collective cause.[footnote 36]

24. In terms of the cognitive dimensions referenced above, it is important to consider that ideology influences terrorists (and others) in dynamic rather than static or rigid ways. Ideological influence might, in this context, be helpfully considered on a spectrum, ranging from being of central importance to individuals to something much more peripheral. Individuals may also travel along this spectrum, in both directions, as they become involved in terrorism. For individual acts of violence to be considered terrorism, ideology must have featured in their motivation and projection, but the weight of this ideological component can vary considerably, as will be demonstrated in the next section.

25. Two additional points need to be considered in this regard. Firstly, ideology can have an emotional impact on individuals even if they have not developed expertise in the particular theories or discourses that underpin that ideology. Religiosity works in similar ways: individuals can feel fervently religious without being experts in theology.[footnote 37] It is notable, for instance, how Arabic-language nashids, religious vocal songs, a common form of cultural expression that is sometimes imitated by terrorist organisations to glorify their actions and strike an emotive chord, have been popular among convicted UK terrorists, even if they do not understand the words. Individuals can identify with such output, especially when combined with other English-language media material, without understanding its precise meaning.

26. Secondly, we need to consider the breadth of roles and undertakings that are associated with terrorism offences beyond direct involvement in terrorism itself. For some of these roles or levels of association, individuals may never have intended to become involved in violence, but rather, for example, felt content with fundraising or sending funds directly themselves. In turn, motivations may vary for different roles and types of involvement, and the role played by ideology.

27. While the definitional and theoretical dimensions traced above are important for our understanding of terrorism and ideology, it is equally important to understand and visualise what this relationship looks like in the real world. Ideology, as noted, is an indispensable component of terrorist motivation, but exists on a spectrum from limited to substantial levels of engagement. At the same time, it coexists with, complements and contextualises other factors leading to terrorism, such as structural drivers, individual incentives and enabling factors.

28. The most direct way in which we can study the role of ideology in terrorist motivation in the UK is through an examination of ideological content that terrorists have collected and engaged with. A survey of the ideological landscapes themselves, such as terrorist propaganda produced by terrorists, or of extremist expression and content found online, does not allow us to make any inferences regarding the types of ideological content that terrorists appeared to have favoured. This study seeks to move beyond such static perspectives and identify what the relationship between involvement in terrorism and selection of ideological content looks like.

29. As noted, prosecutors often rely on ‘mindset material’ to demonstrate the intent of suspected terrorists in court, though much of this material is currently legal. Such mindset material, in turn, sits in a bigger pool of ideological content that reaches into mainstream and moderate discourse. Given its volume and scope, and the fact that ideological material is consistently recovered in UK terrorism investigations, it arguably presents an invaluable – if largely untapped – source of evidence regarding the relationship between terrorism and ideology.

30. Ideological content collected by terrorists can be seen as representing the particular pieces of a broader ideological community to which an individual was drawn. The types of ideological content that convicted terrorists were found to have secured, by extension, can be seen to represent their directly observable and measurable choices and behaviours in this regard, linking their involvement in terrorism with the types of ideological material that appealed to them. The next section examines this material identified in police investigations, with the aim of shedding further light on this relationship between ideology and terrorism.

Ideological content collected by convicted terrorists

31. What follows is an analysis of ideological material collected by 100 convicted terrorists in the UK.[i] This collection consists of the entirety of identified content at the time of arrest, rather than a more limited selection (for instance material that was presented at court). While references to the latter have been mentioned in the press, official reporting and other sources, no other study has examined the entirety of these ideological collections.

32. While these individuals varied in terms of age, sex, nationality, family status, prior criminal record, socio-economic background, observed or diagnosed mental health problems and a variety of other factors, they all undertook to secure different types of media – books, pamphlets, manifestos, blogs, videos, lectures, sermons, songs etc – that conveyed the ideology that was used to rationalise and direct their violence. That alone points to the importance of ideology for terrorists and its presence in transitions towards involvement in such violence.

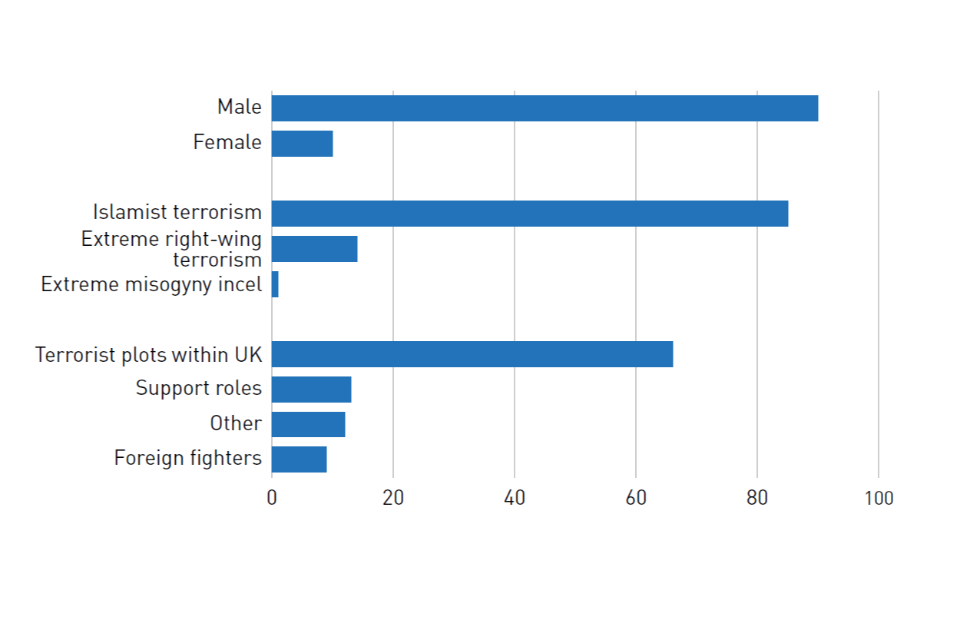

Figure 1: Detail and overview of subjects

[i] While most were convicted in UK courts, some were found guilty through other legal processes, such as inquests following successful attacks. Three factors dictated the choice of subjects: (1) as this is primarily a qualitative study, the number of subjects had to be representative, but manageable; (2) the primary focus was on the most serious terrorist offences (i.e. involvement in advanced or successful plots to kill); (3) a secondary focus was on identifying a smaller cohort of comparable terrorist offences to develop comparative dimension of the study. CTP expertise guided the choice of convicted subjects given the above.

33. While the focus of this review of seized ideological material is on extremist content, it is discussed in the broader context of ideological content, including mild and moderate content that was found as part of the media that was seized from individual subjects as they were investigated for their involvement in terrorism.

34. As noted, the 100 subjects varied greatly in terms of background and characteristics. They included British citizens and foreigners, those with and without prior criminal records, and a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds: from the long-term unemployed to highly educated individuals in skilled jobs. There were 10 women in this dataset; the remainder were men. The ages of subjects, at the time of their arrest, ranged from the mid-teens to the late fifties, and their living status varied greatly: from those living with their families in their own accommodation to those living alone or at no fixed address. Our focus, of course, is not on these characteristics, but rather on the nature of the ideological material they all collected. Nevertheless, it is suffice to say that these subjects did not fit any single ‘profile’.

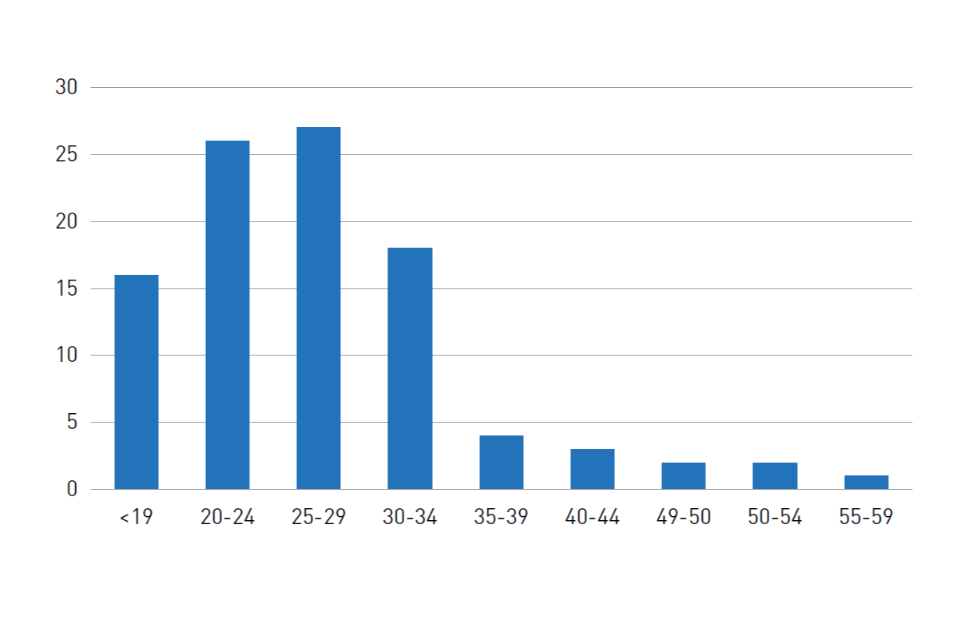

Figure 2: Subject age range

35. Eighty-five individuals were considered to be Islamist terrorists (IT)[footnote 38], 14 were involved in Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism (ERWT)[footnote 39] while one individual was considered an extreme misogynist sympathetic to so-called ‘involuntary celibates’, a subculture that blames women and wider conspiracies for the absence of their romantic relationships.[footnote 40] The focus of the research was on those who had been involved in planning acts of terrorism or had been successful in carrying out such acts (see note i). Sixty-six individuals (61 IT, 5 ERWT) had undertaken advanced attack plans and were sentenced for the most serious terrorism offences.[footnote 41] The remainder were convicted for related offences: joining terrorist organisations abroad (8 IT, 1 ERWT), providing material support (6 IT, 7 ERWT), such as propaganda or fundraising, or were engaged in other types of extremist activity in support of terrorism (10 IT, 1 ERWT, 1 incel) such as non-lethal violence, including arson. The activities for which these individuals were arrested and convicted took place between 2004 and 2021.

36. At the time of their arrest, the 100 convicted terrorists in this study had amassed over 6,000 individual items of ideological material; that is media publications conveying ideological content. 860 items were collected by the 14 far-right extremists, 5,218 by the 85 individuals associated with Islamist extremism. The size of individual collections varied between individuals, irrespective of ideology, depending on their interests, time spent acquiring such material, as well as external factors such as the availability of content and access to computers and the internet. Over time, the nature of acquisition evolved with changes in technology: in the earliest cases individuals sought to acquire printed material or copied digital items on storage devices such as CDs and memory sticks. Later, social media platforms, both public forums and private channels, became the premier ways in which ideological material was acquired, shared and discussed. In general terms, subjects in more recent cases amassed greater amounts of media than those in the older cases, no doubt in part due to greater bandwidth and digital storage and streaming capabilities.

37. To present and make sense of this ideological material, the following analysis will be arranged across three stages. It begins with broad trends identified across the dataset, then narrowing to examine the most popular types of ideological content, before homing in on the main titles and commentators and presenting examples of how this material was consumed. The analysis concludes with two case studies illustrating the way in which ideology featured alongside other developments that preceded involvement in terrorism in a complex web of interconnected factors.

Mapping the ideological landscape

38. Given the volume of material, a simple classification system was devised to categorise these publications according to their substance, to give an initial sense of the type of messaging that this material conveyed. The focus was on identifying material of greatest concern, that conveyed extremist and prejudiced messaging, and separating this from other types of content. To this end, the classification system was arranged across two phases, reflecting the type of ideological content conveyed. The first phase highlighted different attitudes towards outgroups: from neutral to hostile and violently hostile. The three categories were defined as follows (see Appendix 1 for detailed definitions):

- moderate (neutral, no endorsement of violence);

- fringe (isolationist, exclusive, hostile rhetoric without explicit endorsement of lethal violence);

- extreme (support for lethal violence, sometimes contains dehumanising rhetoric);

39. The second phase divided the extreme ideological material into further subcategories (see Appendix 1):

- extreme level 1 (no detail offered in relation to targeting or violence, or when offered, is limited to combatants);

- extreme level 2 (lethal violence promoted/justified against non-combatants, but without detail (e.g. ‘kill the Jews’));

- extreme level 3 (serious violence endorsed against non-combatants with facilitative detail, such as preference for methods (e.g. ‘use martyrdom operations’))

40. The primary purpose of this second phase of classification was to highlight content that went the farthest in prescribing, justifying and glorifying violence, thus unquestionably promoting ‘terrorist’ violence, and different stages concerning such targeting.[footnote 42] This method of classification gives us the tools to compare ideological material against a standardised set of definitions, thus highlighting items of greatest concern and detecting patterns as regards the nature of collected ideological material across cases and over time.

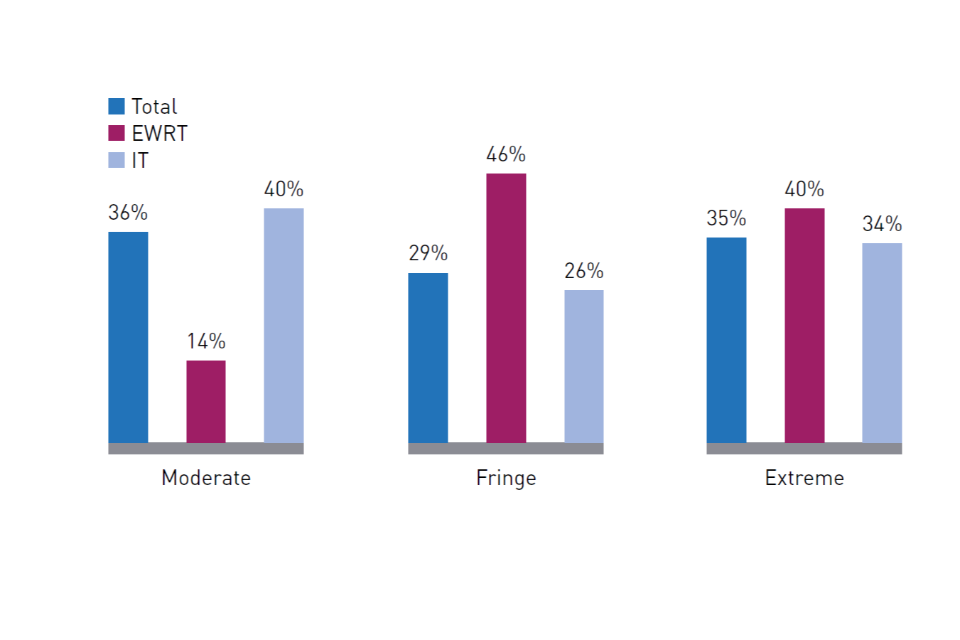

41. The results of this grading revealed that ideological material, broadly defined to include mild and non-extreme content, is relatively evenly distributed between the moderate, fringe and extreme categories as defined above. Therefore, those who went on to be convicted for terrorism did not fixate on extreme ideological material – content that condoned violence – but rather displayed broader ideological interests.

42. However, substantial differences emerged between ideological domains. The ideological material collected by those involved in ERWT gravitated much more towards hostile, intolerant and violent discourses compared with those involved in Islamist extremism. Only 14 percent of ideological content identified in far-right extremist cases was considered moderate in nature, consisting for instance of mainstream political content. This suggests the information environment of these individuals is very narrow and limited to conspiratorial, hostile and extremist rhetoric that is rarely debunked by alternative, mainstream, content.

Figure 3: Grading category for seized ideological material

| Total | EWRT | IT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | 36% | 14% | 40% |

| Fringe | 29% | 46% | 26% |

| Extreme | 35% | 40% | 34% |

N=6,080

43. The ideological interests of Islamist extremists were, according to these results, broader and more clearly focused on a shared objective. While there was a strong concentration of extreme content, including graphically extreme material that glorified mass slaughter of civilians, the distribution across the three categories was more even compared with content from ERWT cases. Two-fifths of the ideological content from IT cases was moderate, and included grievance material that was not violently hostile towards identified outgroups as well as normal religious content, such as historical accounts of religious figures or guides on religious etiquette and practice. This suggests that the IT subjects often had a base interest in or exposure to mainstream religious and political affairs, while developing extremist and prejudiced sympathies in addition to these moderate perspectives. This may also reflect the fact that Islamist extremist views offer violent solutions to achieve religious objectives, such as creating religiously-governed societies that are articulated beyond the extremist realms.

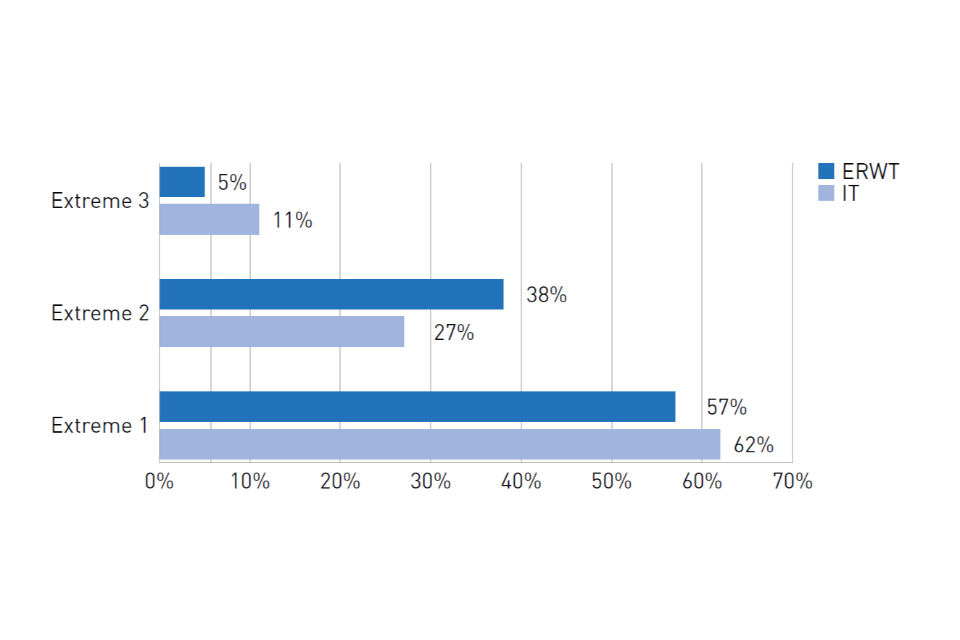

Figure 4: Range of ‘extreme’ – graded material

| ERWT | IT | |

| Extreme 3 | 5% | 11% |

| Extreme 2 | 38% | 27% |

| Extreme 1 | 57% | 62% |

- Extreme 1: no detail on violence/limited to combatants;

- Extreme 2: violence against non-combatants;

- Extreme 3: violence against non-combatants with some facilitative detail

N=1,984

44. There were, however, stark contrasts and contradictions between these categories of material, particularly when it came to treatment of defined out-groups. Subjects appear to overlook or ignore these contrasts, presumably believing the narrative contained in their extreme ideological material, that the path they have chosen is the correct one.

45. Turning to the extreme ideological material favoured by the 100 convicted terrorists in this sample, it was found that most such publications did not convey any detail in terms of the types of violence that was being endorsed. While all this material endorsed lethal violence as a method to achieve change, over half of this content for both ideological domains did not elaborate on what that violence would look like or against whom it should be targeted, beyond the general political context in which these particular narratives were conveyed. The focus was on developing the case in support for violence in principle, often with references to an ingroup or community that needed to be defended.[footnote 43]

46. Between a quarter (IT) and two-fifths (ERWT) of the extreme titles, in turn, called for or endorsed violence against non-combatants in explicit ways, but without elucidating methods, tactics or strategies of violence. Only a small proportion offered more ‘facilitative’ accounts as to how such indiscriminate violence could be orchestrated. A small number of titles within the IT dataset, moreover, embedded specific instructional guidelines – usually bomb-making recipes – in an otherwise ideological narrative. The most well-known of these are English-language magazines that were produced by terrorist organisations, such as Inspire, which was developed by Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the first edition of which contained the article: ‘Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of your Mom’.[footnote 44]

47. From this we can determine that the general focus of extreme ideological material favoured by the 100 convicted terrorists in this sample tended to be on why violence should be embraced, occasionally against whom it should be targeted, often through broad-stroke condemnation of adversaries, but very rarely on how violence should be organised and carried out. This material was weak on detail and served a purpose different from strategic guidance or operational facilitation. It built a narrative whereby lethal violence was seen as proportionate, moral and obligatory in defence of an identified community.

Popularity of ideological content

48. The 100 convicted terrorists in this sample were arrested between 2004 and 2021. Over this period certain patterns emerged in terms of their selection of ideological material. Some titles and authors appeared in repeated investigations and across this time period. This was especially the case for extreme ideological material, that appeared to contain certain staples that were common throughout this period.

49. Two gauges of popularity were developed for this study. The first aggregated the volume of ideological material by author, therefore highlighting the most prolific ideological commentators for the 100 subjects. The second identified individual publications that appeared repeatedly across investigations. Each of these measurements bring their own pros and cons. The former is biased towards those who produced large volumes of individual media items - which is not necessarily a sign of impact - while the second gives more of a snapshot of high-impact content. Together, however, these measurements offer a clear sense of the most popular types of ideological material collected by convicted terrorists in the UK.

Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism (ERWT)

50. When the 862 identified ideological items from ERWT cases were sorted by author, some patterns – though limited – emerged. Overall, the analysis found that ERWT music groups – from folk musicians to heavy metal bands – produced the highest volume of content. The most prolific authors of more substantive ideological content proved to be National Action, founded in 2013 and proscribed by the Home Secretary in December 2016, followed by James Mason, a veteran of the US white supremacist scene who was repopularised by a younger generation of ERWT activists more recently, particularly in relation to his collection of essays titled Siege.

51. Overall, audio material was the most popular type of ideological material in the ERWT dataset (44%), followed by written content (31%) and video material (25%). It should be noted, though, that the ERWT space contains different – and sometimes conflicting – movements internally. As the 2023 CONTEST Strategy noted, the ideologies inherent within ERWT can broadly be characterised as Cultural Nationalism (primarily anti-Islamic and anti-immigrant), White Nationalism (racial separatists) and White Supremacism (racial supremacists, national socialists), though there is overlap between them.[footnote 45] As a consequence, some adherents of cultural nationalism will not identify with core ideological elements of White Supremacism – including grievances, methods for reform and desired end-state – and vice versa, and the same applies to the chief commentators and elements of these ideological elements.

52. As such, a number of ERWTs in this study did not show any interest in the far-right extremist music scene, or indeed material from National Action and James Mason. There were some temporal shifts as well. In the older cases, subjects gravitated towards written content by British neo-Nazi cohorts such as Combat 18, and material from American neo-Nazi promoters such as the ‘World Church of the Creator’, racist novels by William Pierce (such as The Turner Diaries) and David Lane, and WWII Nazi nostalgia. In newer cases, interest in neo-Nazi material was retained, but supplemented by more ‘accelerationist’ and esoteric material in some cases.[ii] Those closer to the cultural nationalist end of the spectrum, meanwhile, engaged less with ideological material and gravitated towards conspiratorial material from a variety of groups and authors.

53. Overall, the most popular titles among the ERWT cohort were the dystopian novels by William Pierce, Hunter and The Turner Diaries, Hitler’s Mein Kampf, a document by George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the American Nazi Party, and two pamphlets by ‘Max Hammer’ on behalf of Blood & Honour, a white supremacist music network founded in the late 1980s.[iii] Notably, however, these publications were eschewed by those of a more cultural nationalist persuasion, who gravitated towards material such as missives by Tommy Robinson (Stephen Yaxley-Lennon), co-founder of the English Defence League. The major ERWT titles are summarised in the boxes below.

[ii] Accelerationism refers to a political position associated with a number of different ideological domains that argues that the only way to reform society is to ‘accelerate’ its collapse.

[iii] ‘Max Hammer’ is an alias, likely to be for a Norwegian white supremacist leader.

Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler (1889-1945)

First published in Germany, 1926.

Mein Kampf (My Struggle) is Adolf Hitler’s famous autobiography, and one of the foundational texts of National Socialism. The book is divided into two volumes, published in 1925 and 1926. The first details Hitler’s life, explaining how he became involved in political activity. The second volume talks about the National Socialist Movement itself. The central theme of the book is that the German people were betrayed in the war of 1914-1918, and forced to submit to a humiliating peace treaty. This betrayal was the result of Jewish and Marxist treachery, as well as the failings of parliamentary democracy. Hitler became involved in political action, eventually joining the NSDAP, in order to rectify this. The solution to this problem, Hitler says, is the establishment of an organic state that prioritises race over all else.

The book is decidedly anti-Semitic throughout. Not only are Jews blamed for Germany’s defeat, but they are frequently dehumanised, and certain passages clearly indicate Hitler’s desire for genocide.

Turner Diaries by William Pierce (1933-2002)

First serialised in the mid-1970s, published as a book in 1978.

The Turner Diaries is a famous piece of far-right fiction, written by William Pierce (under the alias Andrew Macdonald), and published in 1978. The book is narrated by an editor in the year 2099, and it contains the diary of Earl Turner, an activist in the white nationalist revolution of the 1990s. In the story Turner is a rank and file member of the Organization, a far-right group that seeks to resist the tyrannical liberalism of the United States government. Over the course of Turner’s narration, the Organization grows from a small and weak terrorist organization hiding from the System, to overthrowing the US government and creating a world of white supremacy.

Throughout the book Turner celebrates and explicitly justifies acts of mass violence, including against civilians, and he eventually concludes that the entire white race is guilty of acquiescence to Jewish rule. All non-white and Jewish characters are murdered on account of their race. The result is an extremely racist text that has inspired generations of far-right extremists.

Blood & Honour: The Way Forward by “Max Hammer” published in 2000

Blood & Honour: The Way Forward is a pamphlet written by “Max Hammer”, an alias likely to be a veteran member of the far-right group Blood & Honour. It aims to inform and guide “both veterans and the young blood about our Movement and how it should lead its troops into the next century, the millennium of total White power.” It tells national socialists to stop trying to win over ZOG (Zionist Occupation Government) through argument. Instead, they should focus on recruiting sympathetic political soldiers.

The author notes the importance of acting internationally, looking at the example of the pan-Aryan SS. He also stresses the importance of White Power rock in propaganda. Towards the end, the author defends Blood & Honour (B&H)’s comrades in Combat 18, celebrating them for their street violence against “traitors, Reds and zoggies” and calling on them to become the armed wining of B&H. The clear implication is that they should threaten and carry out violence against “Civil servants, politicians, and journalists” who harm the group.

White Power by George Lincoln Rockwell (1918-1967)

Originally published in 1967.

White Power consists of 16 chapters that, in different ways, lay out the purported problem with society, who is responsible for said problems, and what is to be done about it.

The volume begins with the chapter ‘Death Rattle’, where Rockwell lays out what he sees as the degenerate nature of modern society; ‘Spiritual Syphilis’ lays out the spiritual rot that affects Americans; ‘The Chart Forgers’ begins Rockwell’s explanation as to what precisely is wrong with society; ‘Crooked Captains’ describes Marxists who are trying to destroy Western civilization; ‘Closer Look at the Crooks’ focuses on Jews; ‘Friends of the Captain’ and ‘Friends of the Crew’ develop these anti-Semitic tropes further; ‘Black Plague’ is a highly racist diatribe against African-Americans’ which continues in the next chapters; ‘Facts of Race’ and ‘Nightmare’; ‘50 Years of Failure’ talks about the failure of conservatives to confront this danger. “White Imperium” begins the final theme of the book, which is to offer a solution to the problem that has been outlined. This is further developed in ‘White Revolution’; ‘National Socialism’; and ‘White Power’.

Islamist Terrorism (IT)

54. The combined ideological material from Islamist terrorist cases revealed more consistent trends in terms of popularity, when compared with the ERWT cases. When arranged by the most popular authors and producers of ideological material, three key figures emerged as particularly influential. These were:

- Anwar al-Awlaki (1971-2011), a Yemeni-American preacher who became a member of AQAP’s leadership network (see separate box);

- Abu Hamza al-Masri (b. 1958), born Mustafa Kamal Mustafa in Egypt, who became the imam of Finsbury Park Mosque in 1997, turning it into a hive of extremist activity before he was convicted of incitement of terrorism in 2006;

- Abdullah Faisal al-Jamiki (b. 1963), born Trevor William Forrest in Jamaica in 1963, who converted to Islam in his mid-teens. He went on to study in Riyadh before moving to London where, in 2003, he was convicted for inciting murder after a decade-long career as an extremist preacher, giving sermons at over 150 locations across the UK. He was deported upon release, but continued to spread his material via his website, ‘Authentic Tauheed’. He later faced criminal charges in New York, where he was convicted for recruiting for the Islamic State group (IS) in January 2023.[footnote 46]

55. These three figures – but especially Awlaki – were popular both in older and newer cases and all, notably, were primarily focused on delivering audio material (lectures, sermons, stories) in English. Other popular figures included those associated with Al-Muhajiroun (ALM) and Arab jihadi scholars, especially the Palestinian-Jordan writer Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi (b. 1959). Aside from ALM, the most prominent Islamist groups were IS and Al-Qaeda, including members of the latter’s leadership circle such as Usama bin Ladin and Ayman al-Zawahiri.

56. As far as the most popular extreme ideological material was concerned, it was notable that much of this content originated in the West. Moreover, and as already alluded to, almost all this content was in English. Two-fifths of extreme ideological publications were originally authored in the West, mostly the UK and US and included material from radical preachers who were based in those countries. However, in addition to this output, a substantial proportion of extreme ideological material originally published outside the West and in languages such as Arabic had been translated and reproduced by Western-based publishing houses and translation networks that often adjusted the content to appeal specifically to those living in the West. Much of this translation effort was concentrated in the UK.

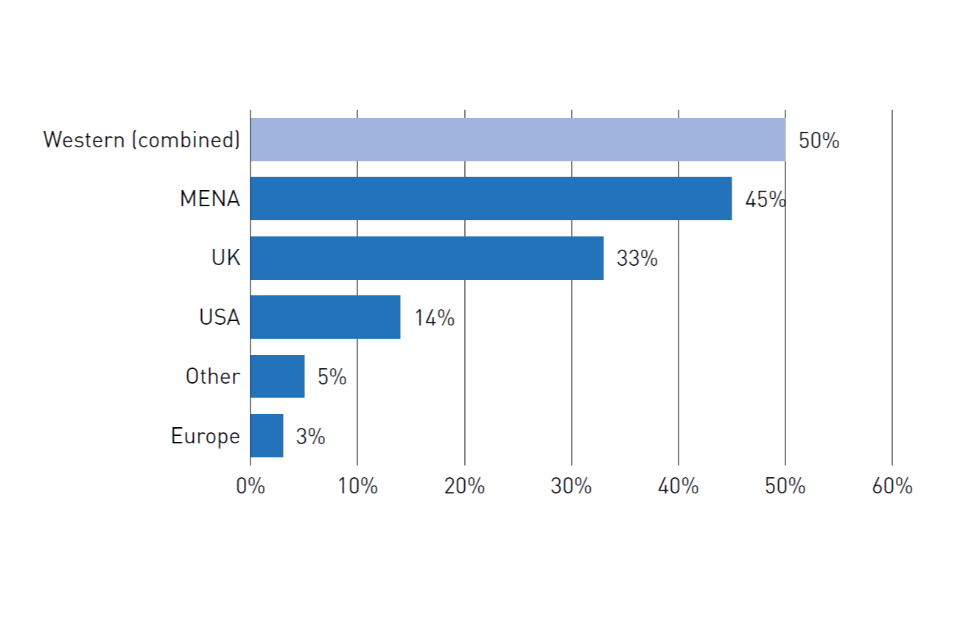

57. While significant amounts of extreme ideological material in the IT cases originated in the MENA region, including material from terrorist organisations such as IS, half the material originated in the West (UK, USA, and Europe).[iv] This geographic distribution points to the truly global nature of the extremist ideological information environment which appeals to those involved in Islamist Terrorism in the UK.

[iv] The author determined the selection of geographic area by publication dates. For example, publications that may have originated in MENA but later translated and ‘re-packaged’ by a UK publishing house (or its less formal equivalents) were deemed to be from the UK.

Figure 5: Geographic origin of extreme ideological material (IT)

| Region | % |

|---|---|

| Western (combined) | 50% |

| MENA | 45% |

| UK | 33% |

| USA | 14% |

| Other | 5% |

| Europe | 3% |

N = 1,447

MENA: Middle East and North Africa

58. This global pool of ideological influence in IT cases is also reflected in the second gauge of popularity, which identifies the most popular titles across cases. This list included contemporary works by English-speaking thinkers – most prominently Anwar al-Awlaki – as well as older content that originated in the MENA region and has since been translated into English. In terms of the latter, fundamental texts on Islamist militancy by Abdallah Azzam and Sayyid Qutb have been consistently popular, as has medieval commentaries on warfare by a Syrian-born scholar called Ibn Nuhaas, which has been adapted to contemporary realities by different commentators including al-Awlaki. It remains hugely popular among UK-based convicted terrorists despite its age, albeit in new and abridged formats

Major IT titles are summarised in the boxes below.

Mashari al-Ashwaq / The Book of Jihad / The Story of Ibn al-Akwa by Abi Zakaryya al Dimashqi al Dumyati, a.k.a. ‘Ibn-Nuhaas’(d. 1412). Adapted by Anwar al-Awlaki (2003) |

The Book of Jihad is a fifteenth century Islamic thesis on holy war. The author – commonly known as Ibn Nuhaas – asserts that waging jihad against the disbelievers is an obligation on Muslims. He makes this point with extensive quotations from the Quran and from narrations. As he does this, Ibn Nuhaas promises that those who wage jihad will receive great rewards in the afterlife, and that the Mujahideen are among the greatest of all Muslims. By contrast, those who shy away from jihad will go to the hellfire. Martyrdom in the cause of Allah is particularly celebrated. Importantly, Ibn Nuhaas’ conception of jihad seems restricted to the battlefield, and he does not explicitly advocate the targeting of non-combatants. However, although the text is over half a millennium old, the text is still very much applicable to contemporary jihadism.

Al-Awlaki’s 12-part lecture series (later published in transcribed form) offers more contemporary interpretations and prescriptions and uses the medieval thesis to justify indiscriminate and mass-casualty violence and glorify suicide attacks. Each lecture includes Awlaki’s commentary and a Q&A session.

Join the Caravan by Abdallah Azzam, originally authored in 1988, later published in English by Azzam Publications and Maktabah al-Ansaar

Join the Caravan is a famous jihadi text written by one of the founding fathers of modern Islamist militancy, Abdallah Azzam. The text is divided into two sections. The first of these looks at the reasons for jihad in the context of the Soviet-Afghan war, and Azzam lists 16 reasons why Muslims should fight. Jihad is portrayed as a way of defending Islam as well as granting Muslims great rewards in paradise. In the second section Azzam excoriates the Muslim world for not engaging in the Afghan jihad. He argues that jihad is an obligation upon Muslims, and describes it as an act of faith equal to praying or fasting. In the English language edition, the original text is supplemented by Azzam’s notes on who is exempt from the obligation of jihad. In this way, Azzam calls upon Muslims to join the caravan of jihad.

Milestones by Sayyid Qutb, 1964

Milestones or Signposts on the Road (Ma’alim fi’l tareeq) is one of the most influential works of contemporary Islamist activism. The book aims to lay out ‘milestones’ or ‘signposts’ to guide Muslims in the creation of a true Muslim society. Essentially, Qutb argues that contemporary Muslims should follow the methodology of the first generation of Muslims, and use the Quran as their sole inspiration. He alleges that the generations which followed the prophet Muhammad were corrupted by ‘Jahiliyyahh’ (pre-Islamic ignorance) influences. This leads Qutb to argue that conflict with the non-Islamic world is inevitable, and he advocates offensive jihad as a way of freeing the world from the oppressive structures of Jahiliyyahh. He concludes by calling for an Islamic society that follows the shariah.

There are many different translations of this widely-read work. In some, references to jihad have been watered down; in others, they have been made more explicit.

The Life of Mohammed by Anwar al-Awlaki (published c.a. 2000)

This popular multi-part lecture series traces the life of the Prophet Mohammed (divided into the Meccan and Medinan Periods) as told by Anwar al-Awlaki.

The Meccan Period follows the life of the prophet from his birth to his migration from Mecca to Medina in 622. Less extreme than the two Medinan series, the Meccan period talks about the lives of believers before Islam, and claims that Muhammad fulfils many of the prophecies in the Christian Bible. As Awlaki narrates stories from the life of the prophet, he frequently segues to commentary about the modern world. In particular, he says that the life of the prophet is important to study because it offers a way to creating a Muslim identity that stands apart from Western materialistic culture.

The Medinan Period is split into two parts. Part 1 follows the life of the prophet from his migration to the city in 622 to the beginning of territorial expansion in 627. Throughout the series, Awlaki captures the conflict between the Muslims and their enemies, which includes the Quraish, the Jews, and internal traitors. The battles of Badr, Uhud, and the Trench feature prominently, and Awlaki uses this to glorify fighting and martyrdom in the name of Allah. The material is also deeply anti-Semitic.

The Medinan Period 2 looks at the prophet Muhammad’s life from 627 to his death in 632. It begins with the conclusion of the war with the Quraish and the conquest of Mecca, before the beginning of the war with the Romans, and the implementation of Islamic law throughout the Arabian Peninsula. Throughout the series, Awlaki compares the actions of the Muslims of this time to the actions of Muslims today. In particular, he urges Muslims to wage jihad and fight for Islam.

The Hereafter by Anwar al-Awlaki published by Al-Basheer in early 2000s

The Hereafter is a lecture series by Anwar al-Awlaki on the topic of the afterlife. These twenty lectures cover seven topics: death, the grave, minor signs of the Day of Judgement, its major signs, the Day of Judgement itself, hell, and heaven. In essence, Awlaki argues that this current life is insignificant compared to the afterlife, and Muslims should use their time to do good deeds that will allow them to enter heaven. The greatest deed that they can do is martyr themselves in the cause of jihad. His discussion about the wonders of heaven, and horrors of hell, only adds to the incentive he creates for the listener to wage jihad.

59. In newer Islamist Terrorism cases, interest in these staples was retained, but was supplemented in particular by material from or in support of terrorist organisations, especially IS. This included videos, nashids and other propaganda output, as well as copies of its English-language magazines Dabiq and Rumiyah.[v] Newer cases also featured more user- or fan-generated content and other unofficial output that glorified Islamist militancy, including memes, as well as less-formal material from nascent publication and production networks.

[v] Dabiq was an online magazine published by the Islamic State between July 2014 and July 2016. In those two years, the rise and fall of the burgeoning caliphate can be seen through the fifteen stylishly produced magazines that were translated into a wide variety of languages. Rumiyah was an online magazine published by the Islamic State between September 2016 and September 2017. It was released in eight languages, including English. The magazine was said to have been the creation of Abu Sulayman ash-Shami (the former editor of Dabiq) and Abu Muhammad al-Furqan from the Islamic State’s media ministry. Each magazine began with a quote from Abu Hamzah al-Muhajir, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s successor as leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq: “O muwahhidin (monotheists), rejoice, for by Allah we will not rest from our jihad except beneath the olive trees of Rumiyah (Rome).” Thirteen issues were published.

Themes across ERW and IT mindset material

60. Despite the range of different ideological domains and periods, the most popular ideological content identified in this research revealed broad themes that emerged prominently for both far-right and Islamist extremist ideological material.

Four stood out:

- a revivalist or utopian theme, with nostalgia for a forsaken past and a desire to re-establish its perceived social equilibrium, whether racial, cultural or religious.

- a salvation theme, with a focus on redemption and personal or collective rebirth, that would cleanse both individual and societal sins and transgressions.

- a community preservation theme, focused not just on the collective welfare of a community, but more distinctly on the ‘purity’ of an in-group, such as the white race, European cultural pedigree or the prophesised ‘saved’ sect of sincere believers.

- a theme of sacred violence, with fighting elevated to an act of devotion where combatants were cheered for their sacrifice and the fallen welcomed as martyrs (or in ERWT material sometimes as ‘saints’).

61. Other themes that we might have expected to find were less common, particularly high-end doctrine or strategic guidance. The focus was very much on collective bonds, pasts and futures. These themes help us to discern the function of ideology for these subjects: to instil a sense of community that needs protecting, to justify extreme measures as proportionate in its defence, and to lay out the objectives of that community and the rewards individuals may enjoy if they contribute towards those objectives.

Consumption and sequences of exposure

62. As noted, all subjects in this study engaged with ideological content – including extreme material – prior to and during their involvement in terrorism. With their varied background and multitude of different push and pull factors that caused them to mobilise to that violence, this ideological engagement was one of the few things all of them had in common. Furthermore, subjects were selective and discerning in their engagement with ideological material. In other words, they did not, for example, bulk download such content and simply store on their devices. There was consistent evidence across cases that individuals had identified and acquired ideological material from wider pools of such content that reflected their interests and needs.

63. But the level and duration of ideological engagement varied. Some spent only a few weeks immersing themselves in ideological content prior to their attack, having had little prior interest in such material, while others had been ideologically engaged for years, even a decade in one case, prior to making plans to carry out acts of terrorism. The weight of ideological engagement, relative to other factors that lead to terrorism, therefore, varies between individuals. From the subjects in this study, it was found that those least engaged ideologically were ERWTs nearer the cultural nationalist end of the spectrum. Their involvement in ideological material tended to be superficial and brief, often coloured by more widespread interest in conspiracy theories and even mainstream media. Those involved in Islamist terrorism and white supremacist forms of ERWT were much more ideologically engaged. Clearly, however, such observations are not universal. Anders Breivik, for instance, would be considered a cultural nationalist, while – judging by his voluminous manifesto – being heavily ideologically engaged.

64. However, given the duration of ideological engagement for many individuals we can surmise that such engagement and interests were often not the trigger or catalyst that prompted individuals to become involved in terrorism. Rather, they were the justificatory context that shaped and channelled that involvement and determined its direction, in terms of leading individuals to pursue acts that sought to advance a political, religious, racial or ideological cause.[vi]

65. For many, ideology helped construct an extremist ‘way of life’, where immersion in extreme material formed part of individuals’ day-to-day activities, both individually and collectively. These individual and collective activities both took two forms: explicit (direct) and implicit (indirect).

[vi] As set out in Section1 of the Terrorism Act (2000).

66. Individuals showed direct signs of ideological engagement. A ringleader of one of the major terrorist plots targeting London in the early 2000s, for instance, kept a folder with ideological material and notes, underlining key excerpts and noting paragraphs where he would seek further guidance from extremist thinkers, in his case Abu Hamza al-Masri with whom he was in direct contact. Several other subjects sought and made direct contact with ideological thinkers, including those who had authored the ideological material they were consuming, reaching them via phone, social media or through their social networks. The thinkers in question invariably appeared receptive to this outreach, offering their comments and support and challenge to other authorities, including subjects’ parents or guardians or more moderate narratives.

67. Jottings and comments were surprisingly common too. One IT subject, for instance, annotated a printed version of the aforementioned Book of Jihad, scribbling additional notes on the margins about the permitted scope of violence that appeared to be from al-Awlaki’s recorded lecture series on the book, thus implying they had absorbed both the medieval commentaries and Awlaki’s more contemporary interpretation. In addition, memos were sometimes found, including compilations from ideological material that supposedly provided collated evidence and justifications for the type of violence and targeting that the subjects had planned. There were notes from study circles, lectures and courses and even, in a couple of examples, evidence of individuals having undergone written exams testing their grasp of particular ideological material. Such exams exist both in the ERWT and IT space and can act both as markers of ideological commitment and benchmarks for involvement in particular extremist communities. Acquiring ideological knowledge and understanding of extreme ideological material, therefore, is seen as a valuable commodity.

68. Over half the subjects in this study authored more substantive ideological content, from books and films to manifestos and shorter missives, letters and statements, including handwritten notes, justifying their involvement in terrorism. Such content was usually directed at a wider population, though some authored such material more privately for family, setting out their reasons for violence that invariably linked to the ideological material that had guided them, sometimes with explicit citations and links.

69. There were other more indirect signs of individual engagement with and consumption of ideological material. Investigations often revealed signs of casual consumption. CDs with recordings of lectures, for instance, were found in vehicles used for hostile reconnaissance in several instances and similar material was found in apartments where attack plans were made. Digital scraps of such consumption, of videos and audio tracks, were often found as part of subjects’ web histories, both as streamed and downloaded content. All the foreign fighters included in this sample had collected both recorded matter and PDF files of key written works on their mobile devices before they travelled abroad to join foreign conflicts.

70. Ideological material coloured the cultural expression of subjects too. Both ERWT and IT subjects donned clothing that reflected some of the soundbites promoted by the ideological content they had consumed. Again, there were digital parallels and equivalents, particularly through the use of online avatars and profiles that reflected the ideological position of individual subjects through use of adopted nicknames, memes and profile pictures.

71. Knowledge of ideological material was also social currency for subjects when they interacted with other likeminded people, an interaction most of them sought. A large majority of subjects were found to have engaged with forums discussing ideology, including specific extremist ideas and thinkers, and sharing ideological material. These were both physical and virtual. The former included formal study circles with curricula, assigned readings, and exams, as well as less formal meet-ups. The latter involved social media study groups, channels and online chatrooms.

72. While the popularity of these forums endured – for both ERWTs and ITs – their format evolved over time. In early cases, individuals met in person or joined dedicated chatgroups hosted on websites that often had explicit ideological objectives. After social media platforms became ubiquitous, these discussions mostly moved to platforms like WhatsApp, Telegram and Discord, though face-to-face interactions remained important.

73. For subjects in IT cases, WhatsApp groups and study circles were especially popular. These included female-only forums and were often dedicated to particular ideological topics or the generation, retention and spread of ‘knowledge’, as it was often referred to, which implied extremist ideological interpretations.

74. One cell leader participated in three such groups with dozens of other individuals, who exchanged almost six thousand messages in just over a year. Group members spoke of their desire to increase their knowledge and thus prepare for the Day of Judgement. The cell leader whose investigation provided access to these exchanges urged fellow group members to guarantee their ascent to heaven by fighting the unbelievers until they were slain, thus ushering them to the “highest rooms of Paradise” where, he promised, there would be “unlimited fun.” WhatsApp group members exchanged copious amounts of ideological content and even offered their own theological exegeses via recorded voice messages. Grievances were shared, the “taghut” (idolaters), Jews, Christians, Shia and “red carpet scholars-for-dollars” were condemned, and the community spoke of qualifying as the ghurabaa, the uncorrupted minority promised in ahadith and frequently invoked by extremists.[footnote 47] One study circle participant uploaded a picture of IS fighters declaring: “I want to be like them.”

75. Private Telegram channels involved even more people, including several hundred in some cases. These were often used to distribute and identify new items of propaganda or to discuss its significance. Members also used these forums to encourage ideological consumption. For instance, one cell leader of a foiled plot reported to his Telegram channel that he was struggling to read a book by Abu Qatada, an ideologue once described as Usama bin Ladin’s “right-hand man in Europe”.[footnote 48] His fellow-members spurred him on. Members also asked for advice when encountering various ideologically-flavoured challenges. One prominent topic was how to confront friends and family who disagreed with them. A common response to such queries was to point family members towards some of the group’s favoured speakers, particularly individuals such as Anwar al-Awlaki. In one forum, a member of a group shared his frustration with trying to convince a sibling about the merits of his extremist views. His fellow members responded: “Triple A lol”, referring to Anwar al-Awlaki and: “Exactly. Give her AA.”

76. Right-wing extremists were similarly animated on online forums. Older generations favoured invite-only chatrooms, and often frequented several such forums simultaneously, though conversations were invariably in the same race-obsessed vein, laced with entrenched paranoia about in-group betrayal. One group even established its own “Aryan only” online portal which, at its peak, counted almost 400 members, all with predicably far-right flavoured avatars, invariably formulaic plays on the numeric symbolism of ‘1488’ and its derivatives. There were 50 separate forums on the portal, divided by topic into areas covering recommended literature and e-books, discussions about national socialism, tips on fitness and preparedness, news and current affairs, updates from allied groups and sister organisations, as well as an area for new members to introduce themselves and even present their national socialist artwork.

77. Later generations of white supremacists in the dataset were equally animated by politics, race and their accelerationist-flavoured eschatology. A pair of self-proclaimed national socialist promoters of Mason’s Siege were heavily engaged on Discord, originally a gaming platform that since became a hub for other interests, including radical politics. They frequented several Discord servers focused on political, social, theological and philosophical debates and ranging from Siege fan groups to more diverse, though not necessarily less extreme, political discussion. In fact, a favourite activity of those in the former was to ‘raid’ the latter with calls to “read Siege”, or even to ‘nuke’ them: rendering them inoperable through spamming. This of course often led to the users being banned, but they were quick to re-join, with slightly altered avatars and Virtual Private Network (VPN) connections that gave them a new Internet Protocol address. Favoured servers included the more generic ‘Politics 101’, a common target of raids, though notably, it too tolerated various forms of far-right views among a broader political spectrum of attitudes. More extreme forums were also frequented. While their lifespan was often limited, they were usually quickly re-established, often with very slightly modified names, but a structure and membership that mirrored their predecessor.

78. In all these discussions, national socialism – or ‘natsoc’ – was presented as a perfectly viable alternative on par with other social and political interpretations. Its position on capitalism was discussed in relation to macro-economics, for instance, and ‘Strasserism’ was suggested for those who identified as more working class. Class and distribution of wealth were prominent themes in general. There was talk of being “redpilled” – enlightened – by Hitler speeches, whilst not “agreeing with everything” in them. There were also other cultural references beyond heavy literature, and plenty of ‘shitposting’, or ironic trolling. Extreme misogyny including encouragement of rape, was common in these discussions. Such topics were the dedicated focus of discussion in the so-called ‘incel’ forums frequented by the sole subject included in this study who was influenced by such ideas.