The future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union (HTML Version)

Updated 17 July 2018

Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty

July 2018

Cm 9593

ISBN 978-1-5286-0701-8

CCS0718050590-001 07/18

1. Foreword by the Prime Minister

In the referendum on 23 June 2016 – the largest ever democratic exercise in the United Kingdom – the British people voted to leave the European Union.

And that is what we will do – leaving the Single Market and the Customs Union, ending free movement and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice in this country, leaving the Common Agricultural Policy and the Common Fisheries Policy, and ending the days of sending vast sums of money to the EU every year. We will take back control of our money, laws, and borders, and begin a new exciting chapter in our nation’s history.

It now falls to us all to write that chapter. That is why over the last two years I have travelled up and down the country, listening to views from all four nations of our United Kingdom and every side of the debate. One thing has always been clear – there is more that binds this great country together than divides it. We share an ambition for our country to be fairer and more prosperous than ever before.

We are an outward-facing, trading nation; we have a dynamic, innovative economy; and we live by common values of openness, the rule of law, and tolerance of others.

Leaving the EU gives us the opportunity to deliver on that ambition once and for all – strengthening our economy, our communities, our union, our democracy, and our place in the world, while maintaining a close friendship and strong partnership with our European neighbours.

But to do so requires pragmatism and compromise from both sides.

At the very start of our negotiations, the Government set out the principles which would guide our approach – and the EU set out theirs. Some of those principles, as you would expect, were in tension. Some of the first proposals each side advanced were not acceptable to the other. That is inevitable in a negotiation. So we have evolved our proposals, while sticking to our principles. The proposal set out in this White Paper finds a way through which respects both our principles and the EU’s.

This was the spirit in which my Cabinet agreed a way forward at Chequers. It is the spirit in which my Government has approached this White Paper. And it is the spirit in which I now expect the EU to engage in the next phase of the negotiations.

Our proposal is comprehensive. It is ambitious. And it strikes the balance we need – between rights and obligations.

It would ensure that we leave the EU, without leaving Europe.

It would return accountability over the laws we live by to London, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast, and end the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice in the UK.

It would preserve the UK’s and the EU’s frictionless access to each other’s markets for goods, protecting jobs and livelihoods on both sides, and propose new arrangements for services.

It would meet our shared commitments to Northern Ireland and Ireland through the overall future relationship, in a way that respects the EU’s autonomy without harming the UK’s constitutional and economic integrity.

It would end free movement, taking back control of the UK’s borders.

It would see the UK step out into the world, driving forward an independent trade policy by striking trade deals with new friends and old allies.

It would maintain the shared security capabilities that keep citizens in the UK and the EU safe, as we work in partnership with Member States to tackle crime and terrorism.

It would end vast annual contributions to the EU budget, releasing funds for domestic priorities – in particular our long-term plan for the NHS.

It would take us out of the Common Agricultural Policy and Common Fisheries Policy, ensuring we can better meet the needs of farming and fishing communities.

It would maintain our current high standards on consumer and employment rights and the environment.

And it would enable co-operation to continue in areas including science and international development, improving people’s lives within and beyond Europe’s borders.

In short, the proposal set out in this White Paper would honour the result of the referendum.

It would deliver a principled and practical Brexit that is in our national interest, and the UK’s and the EU’s mutual interest.

So together we must now get on and deliver it – securing the prosperity and the security of our citizens for generations to come.

PRIME MINISTER

RT HON THERESA MAY MP

2. Foreword by the Secretary of State

Leaving the European Union involves challenge and opportunity. We need to rise to the challenge and grasp the opportunities.

Technological revolutions and scientific transformations are driving major changes in the global economy. In line with our modern Industrial Strategy, this Government is determined to make sure the UK is ready to lead the industries of the future and seize the opportunities of global trade.

At the same time, we need to cater for the deeply integrated supply chains that criss-cross the UK and the EU, and which have developed over our 40 years of membership.

The plan outlined in this White Paper delivers this balance.

It would take the UK out of the Single Market and the Customs Union.

It would give the UK the flexibility we need to strike new trade deals around the world, in particular breaking new ground for agreements in services.

It would maintain frictionless trade in goods between the UK and the EU through a new free trade area, responding to the needs of business.

It would deliver on both sides’ commitments to Northern Ireland and Ireland, avoiding a hard border without compromising the EU’s autonomy or UK sovereignty.

This is the right approach – for both the UK and for the EU. The White Paper sets out in detail how it would work. Alongside this unprecedented economic partnership, we also want to build an unrivalled security partnership, and an unparalleled partnership on cross-cutting issues such as data, and science and innovation.

And to bolster this cooperation, we will need a new model of working together that allows the relationship to function smoothly on a day-to-day basis, and respond and adapt to new threats and global shifts while taking back control of our laws.

The White Paper details our proposals in all of these areas, setting out a comprehensive vision for the future relationship.

It is a vision that respects the result of the referendum, and delivers a principled and practical Brexit.

RT HON DOMINIC RAAB MP

SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION

3. Executive Summary

The United Kingdom will leave the European Union on 29 March 2019 and begin to chart a new course in the world.

The Government will have delivered on the result of the 2016 referendum – the biggest democratic exercise in this country’s history. And it will have reached a key milestone in its principal mission – to build a country that works for everyone. A country that is stronger, fairer, more united and more outward-looking.

4. A detailed vision

To fulfil that mission, the Government is advancing a detailed proposal for a principled and practical Brexit.

This proposal underpins the vision set out by the Prime Minister at Lancaster House, in Florence, at Mansion House and in Munich, and in doing so addresses questions raised by the EU in the intervening months – explaining how the relationship would work, what benefits it would deliver for both sides, and why it would respect the sovereignty of the UK as well as the autonomy of the EU.

At its core, it is a package that strikes a new and fair balance of rights and obligations.

One that the Government hopes will yield a redoubling of effort in the negotiations, as the UK and the EU work together to develop and agree the framework for the future relationship this autumn.

5. A principled Brexit

A principled Brexit means respecting the result of the referendum and the decision of the UK public to take back control of the UK’s laws, borders and money – and doing so in a way that supports the Government’s wider objectives across five key areas of the UK’s national life.

For the economy, developing a broad and deep economic relationship with the EU that maximises future prosperity in line with the modern Industrial Strategy and minimises disruption to trade between the UK and the EU, protecting jobs and livelihoods – at the same time making the most of trading opportunities around the world.

For communities, addressing specific concerns voiced in the referendum by ending free movement and putting in place a new immigration system, introducing new independent policies to support farming and fishing communities, using the Shared Prosperity Fund to spark a new wave of regeneration in the UK’s towns and cities, and keeping citizens safe.

For the union, meeting commitments to Northern Ireland by protecting the peace process and avoiding a hard border, safeguarding the constitutional and economic integrity of the UK, and devolving the appropriate powers to Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast – while ensuring the deal delivers for the Crown Dependencies, Gibraltar and the other Overseas Territories, noting there will be no change in their long-standing relationships with the UK.

For democracy, leaving the EU’s institutions and reclaiming the UK’s sovereignty, ensuring the laws people live by are passed by those they elect and enforced by UK courts, with clear accountability to the people of the UK.

For the UK’s place in the world, continuing to promote innovation and new ideas, asserting a fully independent foreign policy, and working alongside the EU to promote and protect shared European values of democracy, openness and liberty.

5.1 A new relationship

Guided by these principles, the Government is determined to build a new relationship that works for both the UK and the EU . One which sees the UK leave the Single Market and the Customs Union to seize new opportunities and forge a new role in the world, while protecting jobs, supporting growth and maintaining security cooperation.

The Government believes this new relationship needs to be broader in scope than any other that exists between the EU and a third country. It should reflect the UK’s and the EU’s deep history, close ties, and unique starting point . And it must deliver real and lasting benefits for both sides, supporting shared prosperity and security – which is why the Government is proposing to structure the relationship around an economic partnership and a security partnership.

The future relationship also needs to be informed by both the UK and the EU taking a responsible approach to avoiding a hard border between Northern Ireland and Ireland, in a way that respects the constitutional and economic integrity of the UK and the autonomy of the EU.

5.2 Economic partnership

In designing the new trading relationship, the UK and the EU should therefore focus on ensuring continued frictionless access at the border to each other’s markets for goods .

To deliver this goal, the Government is proposing the establishment of a free trade area for goods.

This free trade area would protect the uniquely integrated supply chains and ‘just‑in‑time’ processes that have developed across the UK and the EU over the last 40 years, and the jobs and livelihoods dependent on them, ensuring businesses on both sides can continue operating through their current value and supply chains. It would avoid the need for customs and regulatory checks at the border, and mean that businesses would not need to complete costly customs declarations. And it would enable products to only undergo one set of approvals and authorisations in either market, before being sold in both.

As a result, the free trade area for goods would see the UK and the EU meet their shared commitments to Northern Ireland and Ireland through the overall future relationship. It would avoid the need for a hard border between Northern Ireland and Ireland, without harming the internal market of the UK – doing so in a way that fully respects the integrity of the EU’s Single Market, Customs Union, and its rules-based framework.

These close arrangements on goods should sit alongside new ones for services and digital, giving the UK the freedom to chart its own path in the areas that matter most for its economy. The Government wants to minimise new barriers to trade between the UK and the EU, and hopes that both sides will work together to reduce them further over time – but acknowledges that there will be more barriers to the UK’s access to the EU market than is the case today.

Finally, a relationship this deep will need to be supported by provisions giving both sides confidence that the trade that it facilitates will be both open and fair. So the Government is proposing reciprocal commitments that would ensure UK businesses could carry on competing fairly in EU markets, and EU businesses operating in the UK could do the same.

On this basis, the Government’s vision is for an economic partnership that includes:

- a common rulebook for goods including agri-food, covering only those rules necessary to provide for frictionless trade at the border – meaning that the UK would make an upfront choice to commit by treaty to ongoing harmonisation with the relevant EU rules, with all those rules legislated for by Parliament or the devolved legislatures;

- participation by the UK in those EU agencies that provide authorisations for goods in highly regulated sectors – namely the European Chemicals Agency, the European Aviation Safety Agency, and the European Medicines Agency – accepting the rules of these agencies and contributing to their costs, under new arrangements that recognise the UK will not be a Member State;

- the phased introduction of a new Facilitated Customs Arrangement that would remove the need for customs checks and controls between the UK and the EU as if they were a combined customs territory, which would enable the UK to control its own tariffs for trade with the rest of the world and ensure businesses paid the right or no tariff, becoming operational in stages as both sides complete the necessary preparations;

- in combination with no tariffs on any goods, these arrangements would avoid any new friction at the border, and protect the integrated supply chains that span the UK and the EU, safeguarding the jobs and livelihoods they support;

- new arrangements on services and digital, providing regulatory freedom where it matters most for the UK’s services-based economy, and so ensuring the UK is best placed to capitalise on the industries of the future in line with the modern Industrial Strategy, while recognising that the UK and the EU will not have current levels of access to each other’s markets;

- new economic and regulatory arrangements for financial services, preserving the mutual benefits of integrated markets and protecting financial stability while respecting the right of the UK and the EU to control access to their own markets – noting that these arrangements will not replicate the EU’s passporting regimes;

- continued cooperation on energy and transport – preserving the Single Electricity Market in Northern Ireland and Ireland, seeking broad cooperation on energy, developing an air transport agreement, and exploring reciprocal arrangements for road hauliers and passenger transport operators;

-

a new framework that respects the UK’s control of its borders and enables UK and EU citizens to continue to travel to each other’s countries, and businesses and professionals to provide services – in line with the arrangements that the UK might want to offer to other close trading partners in the future; and

- in light of the depth of this partnership, binding provisions that guarantee an open and fair trading environment – committing to apply a common rulebook for state aid, establishing cooperative arrangements between regulators on competition, and agreeing to maintain high standards through non-regression provisions in areas including the environment and employment rules, in keeping with the UK’s strong domestic commitments.

Taken together, such a partnership would see the UK and the EU meet their commitments to Northern Ireland and Ireland through the overall future relationship : preserving the constitutional and economic integrity of the UK; honouring the letter and the spirit of the Belfast (‘Good Friday’) Agreement; and ensuring that the operational legal text the UK will agree with the EU on the ‘backstop’ solution as part of the Withdrawal Agreement will not have to be used.

And while what the Government is proposing is ambitious in its breadth and depth, it is also workable and delivers on the referendum result – fully respecting the sovereignty of the UK, just as it respects the autonomy of the EU – with Parliament having the right to decide which legislation it adopts in the future, recognising there could be proportionate implications for the operation of the future relationship where the UK and the EU had a common rulebook.

In short, this proposal represents a fair and pragmatic balance for the future trading relationship between the UK and the EU – one that would protect jobs and livelihoods, and deliver an outcome that is truly in the interests of both sides.

5.3 Security partnership

Europe’s security has been and will remain the UK’s security, which is why the Government has made an unconditional commitment to maintain it.

During the UK’s membership of the EU, it has worked with all Member States to develop a significant suite of tools that supports the UK’s and the EU’s combined operational capabilities, and helps keep citizens safe. It is important that the UK and the EU continue that cooperation, avoiding gaps in operational capability after the UK’s withdrawal.

The UK will no longer be part of the EU’s common policies on foreign, defence, security, justice and home affairs. Instead, the Government is proposing a new security partnership that maintains close cooperation – because as the world continues to change, so too do the threats the UK and the EU both face .

On this basis, the Government’s vision is for a security partnership that includes:

- maintaining existing operational capabilities that the UK and the EU deploy to protect their citizens’ security, including the ability for law enforcement agencies to share critical data and information and practical cooperation to investigate serious criminality and terrorism – cooperating on the basis of existing tools and measures, amending legislation and operational practices as required and as agreed to ensure operational consistency between the UK and the EU;

- participation by the UK in key agencies, including Europol and Eurojust – providing an effective and efficient way to share expertise and information, with law enforcement officers and legal experts working in close proximity so they can coordinate operations and judicial proceedings quickly – accepting the rules of these agencies and contributing to their costs under new arrangements that recognise the UK will not be a Member State;

- arrangements for coordination on foreign policy, defence and development issues – acting together to tackle some of the most pressing global challenges where it is more effective to work side-by-side, and continuing to deploy the UK’s significant assets, expertise, intelligence and capabilities to protect and promote European values;

- joint capability development, supporting the operational effectiveness and interoperability of the UK’s and the EU’s militaries, and bolstering the competitiveness of the European defence industry, delivering the means to tackle current and future threats; and

- wider cooperation, taking a ‘whole of route’ approach to tackle the causes of illegal migration, establishing a strategic dialogue on cyber security, putting in place a framework to support cooperation on counter-terrorism, offering support and expertise on civil protection and working together on health security.

5.4 Cross-cutting and other cooperation

Finally, the Government believes the future relationship should include areas of cooperation that sit outside of the two core partnerships, but which are still of vital importance to the UK and the EU. These include:

-

the protection of personal data, ensuring the future relationship facilitates the continued free flow of data to support business activity and security collaboration, and maximises certainty for business;

-

collective endeavours to better understand and improve people’s lives within and beyond Europe’s borders – establishing cooperative accords for science and innovation, culture and education, development and international action, defence research and development, and space, so that the UK and the EU can continue to work together in these areas, including through EU programmes, with the UK making an appropriate financial contribution; and

-

fishing, putting in place new arrangements for annual negotiations on access to waters and the sharing of fishing opportunities based on fairer and more scientific methods – with the UK an independent coastal state.

6. A practical Brexit

To deliver the kind of practical relationship needed to secure prosperity for the UK and the EU, and maintain the security of UK and EU citizens, both sides will need to be confident they can trust and rely on the commitments made to each other .

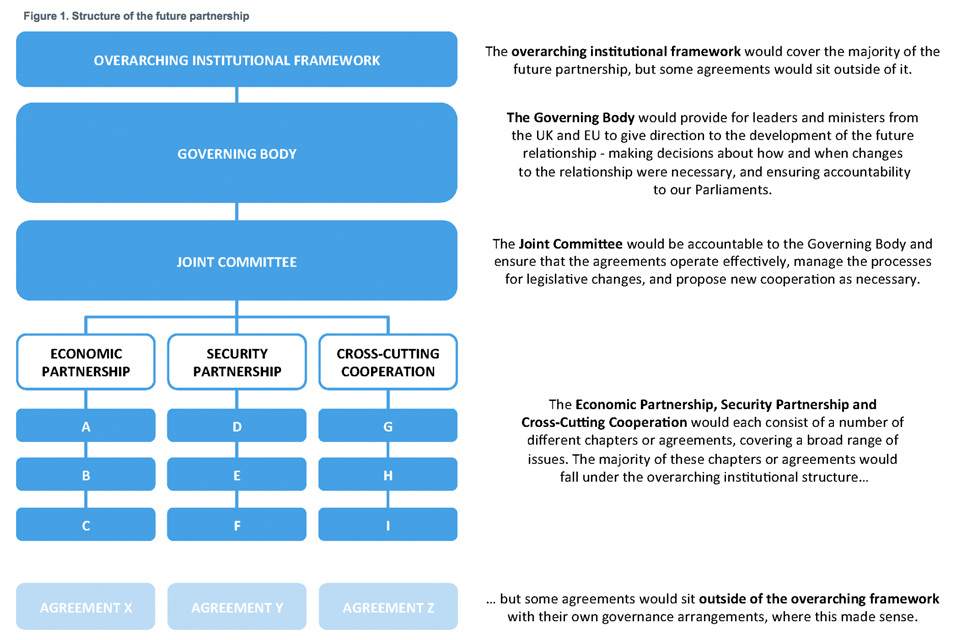

So to underpin the future relationship, the Government is proposing joint institutional arrangements that provide for proper democratic accountability, allow for the relationship to develop over time, mean cooperation can be managed effectively and enable the UK and the EU to address issues as they arise.

These arrangements, which could take the form of an Association Agreement, would ensure the new settlement is sustainable – working for the citizens of the UK and the EU now and in the future.

They would provide for regular dialogue between UK and EU leaders and ministers, commensurate with the depth of the future relationship and recognising the significance of each other’s global standing.

They would support the smooth functioning of the relationship, underpinning the various forms of regulatory cooperation agreed between the UK and the EU. Where the UK had made a commitment to the EU, including in those areas where the Government is proposing the UK would remain party to a common rulebook, there would be a clear process for updating the relevant rules, which respected the UK’s sovereignty and provided for Parliamentary scrutiny.

The arrangements would include robust and appropriate means for the resolution of disputes, including through a Joint Committee and in many areas through binding independent arbitration – accommodating through a joint reference procedure the role of the Court of Justice of the European Union as the interpreter of EU rules, but founded on the principle that the court of one party cannot resolve disputes between the two.

And they would make sure both the UK and the EU interpreted rules consistently – with rights enforced in the UK by UK courts and in the EU by EU courts, with a commitment that UK courts would pay due regard to EU case law in only those areas where the UK continued to apply a common rulebook.

Finally, these arrangements would enable flexibility, ensuring the UK and the EU could review the relationship, responding and adapting to changing circumstances and challenges over time.

7. Moving forward

The Government believes this proposal for a principled and practical Brexit is the right one – for the UK and for the EU.

It would respect the referendum result, and deliver on its promise, while ensuring the UK leaves the EU without leaving Europe – striking a new balance of rights and obligations that is fair to both sides.

In keeping with the spirit of Article 50, and both sides’ commitment to the principle that ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed’, the Withdrawal Agreement and the framework for the future relationship are inextricably linked – and so must be concluded together.

Both sides will need to focus on turning the ‘Future Framework’ into legal text as soon as possible, before ratifying the binding agreements to give it effect – with the aim of ensuring a smooth and orderly transition from the implementation period into the future relationship.

On the basis of this proposal, the Government will now charge the UK’s negotiating team to engage with the EU’s at pace, working to reach a substantive agreement on the Future Framework alongside the Withdrawal Agreement later this year.

8. Chapter 1 – Economic partnership

9. 1.1 Summary

1. Following the decision of the people of the UK in the referendum, the UK is leaving the EU, and as a result will leave the Single Market and the Customs Union – seizing new opportunities and forging a new role in the world. At the same time, the UK wants to protect jobs and support growth through a new economic partnership with its nearest neighbours. This proposal respects the UK’s sovereignty, building in a clear role for Parliament, and preserves the constitutional and economic integrity of the UK’s own Union.

2. A deep and comprehensive economic partnership between the UK and the EU would have distinct benefits for both sides. The UK is the world’s fifth largest economy,[footnote 1] and the EU is the UK’s biggest market. [footnote 2] The UK’s proposal, set out in this chapter, reflects the unique ties that exist between the UK and the EU economies, businesses and consumers. It represents a serious offer, which the Government believes would benefit the UK and its close partners in the EU. In formulating this offer, the Government has listened carefully to the positions that the EU has set out. This proposal respects the EU’s autonomy and the integrity of the Single Market. These principles, together with strong reciprocal commitments on open and fair trade, and propositions for a new institutional framework, inform the design of the UK’s proposal. The UK hopes that this will be the basis of a serious and detailed negotiation in the coming weeks and months that will lead to a historic agreement in the interests of both sides.

3. At the core of the UK’s proposal is the establishment by the UK and the EU of a free trade area for goods. This would avoid friction at the border and ensure both sides meet their commitments to Northern Ireland and Ireland through the overall future relationship. It would protect the uniquely integrated supply chains and ‘just-in-time’ processes that have developed across the UK and the EU over the last 40 years, and will remain important given our geographical proximity, and the jobs and livelihoods dependent on them.

4. These close arrangements on goods would sit alongside new arrangements for services and digital, recognising that the UK and the EU will not have current levels of access to each other’s markets in the future. This would provide regulatory flexibility that is important for the UK’s services-based economy.

5. Every trading relationship has varying levels of market access, depending on the respective interests of the countries involved. The EU has adopted different agreements with countries beyond its borders and outside the Single Market, which are tailored to the depth and nature of its relationships with the countries concerned. It is right for the UK and the EU to take a similarly tailored approach.

6. At the same time, the UK recognises that the Single Market is built on a balance of rights and obligations, and that the UK cannot have all the benefits of membership of the Single Market without its obligations. The UK’s proposal therefore establishes a new framework that holds rights and obligations in a fair but different balance. This would be to the economic advantage of both the UK and the EU. It is a principled and practical response to a unique situation, and offers a constitutionally appropriate solution to the UK and the EU’s commitments on the Northern Ireland/Ireland border.

7. The UK’s proposal for the economic partnership would:

a. establish a new free trade area and maintain a common rulebook for goods, including agri-food, covering only those rules necessary to provide for frictionless trade at the border. The common rulebook would be legislated for in the UK by the UK Parliament and the devolved legislatures, as set out in detail in chapter 4. The UK would also seek participation in EU agencies that facilitate goods being placed on the EU market, and the phased introduction of a new Facilitated Customs Arrangement (FCA);

b. include new arrangements on services and investment that provide regulatory flexibility, recognising that the UK and the EU will not have current levels of access to each other’s markets, with new arrangements on financial services that preserve the mutual benefits of integrated markets and protect financial stability, noting that these could not replicate the EU’s passporting regimes;

c. end free movement, giving the UK back control over how many people come to live in the UK;

d. include a new framework that respects the UK’s control of its borders, enabling UK and EU citizens to continue to travel to each other’s countries and businesses and professionals to provide services, and to help students and young people to enjoy the opportunities and experiences available in the UK and the EU – in line with the arrangements that the UK might want to offer to other close trading partners in the future;

e. include new arrangements on digital trade, including e-commerce, which enable the UK and the EU to respond nimbly to the new opportunities and challenges presented by emerging technologies, recognising that the UK and the EU will not have current levels of access to each other’s markets;

f. incorporate binding provisions related to open and fair competition, with a common rulebook for state aid, cooperative arrangements on competition, and reciprocal commitments to maintain current high standards through non‑regression provisions in other areas, such as environmental and employment rules. The UK has already made strong domestic commitments to maintaining high standards;

g. provide for socio-economic cooperation in areas including energy, transport and civil judicial cooperation; and

h. be consistent with the UK’s ambitions as a global trading nation, with its own independent trade policy – able to represent itself at the World Trade Organization (WTO), to make credible and balanced offers to third country trading partners, and to implement a trade remedies and sanctions regime.

8. The UK will be seeking specific arrangements for the Crown Dependencies, Gibraltar and the other Overseas Territories. [footnote 3] These arrangements should take account of the significant and mutually beneficial economic ties between these economies and EU Member States, including their overseas countries and territories.

10. 1.2 Goods

9. The UK and the EU have deeply integrated goods markets, covering manufactured, agricultural, food and fisheries products. The UK is an important market for the EU, and vice versa. In 2017 the value of imports and exports between the UK and the EU stood at over £423 billion, with the UK reporting an overall trade deficit in goods with the EU of £95 billion.[footnote 4] In the same year, the EU accounted for 70 per cent of UK agricultural imports.[footnote 5] The close trading relationship between the UK and the EU has developed over many decades. It will continue to be important in the future, given the importance of geographical proximity for goods trade.

10. While there has been a trend towards the opening up of services markets, existing trading relationships involve greater liberalisation on goods than on services. Regulatory frameworks draw a distinction between goods, which are physical products that tangibly cross a border, and services.

11. The UK proposes the establishment of a free trade area for goods, including agri‑food. This would avoid friction at the border, protect jobs and livelihoods, and ensure that the UK and the EU meet their commitments to Northern Ireland and Ireland through the overall future relationship. The UK and the EU would maintain a common rulebook for goods including agri-food, with the UK making an upfront choice to commit by treaty to ongoing harmonisation with EU rules on goods, covering only those necessary to provide for frictionless trade at the border. This common rulebook would be legislated for by the UK Parliament, as set out in detail in chapter 4.

12. The UK’s proposal for a free trade area includes:

a. the phased introduction of a new Facilitated Customs Arrangement that would remove the need for customs checks and controls between the UK and the EU as if in a combined customs territory, while enabling the UK to control tariffs for its own trade with the rest of the world and ensure businesses pay the right tariff;

b. the elimination of tariffs, quotas and routine requirements for rules of origin for goods traded between the UK and the EU;

c. a common rulebook for manufactured goods, alongside UK participation in EU agencies that facilitate goods being placed on the EU market;

d. a common rulebook for agriculture, food and fisheries products, encompassing rules that must be checked at the border, alongside equivalence for certain other rules, such as wider food policy; and

e. robust domestic market surveillance and cooperation between the UK and the EU to ensure the rules are upheld in both markets.

10.1 1.2.1 Facilitated Customs Arrangement

13. Upon its withdrawal from the EU, the UK will leave the Customs Union. The UK has been clear that it is seeking a new customs arrangement that provides the most frictionless trade possible in goods between the UK and the EU, while allowing the UK to forge new trade relationships with partners around the world. The arrangement must also allow the EU to protect the integrity of its Single Market and Customs Union.

14. The UK’s proposal is to agree a new FCA with the EU. As if in a combined customs territory with the EU, the UK would apply the EU’s tariffs and trade policy for goods intended for the EU. The UK would also apply its own tariffs and trade policy for goods intended for consumption in the UK.

15. Mirroring the EU’s customs approach at its external border would ensure that goods entering the EU via the UK have complied with EU customs processes and the correct EU duties have been paid. This would remove the need for customs processes between the UK and the EU, including customs declarations, routine requirements for rules of origin, and entry and exit summary declarations. Together with the wider free trade area, the FCA would preserve frictionless trade for the majority of UK goods trade, and reduce frictions for UK exporters and importers. The UK’s goal is to facilitate the greatest possible trade, whether with the EU or the rest of the world.

16. This would mean:

a. where a good reaches the UK border, and the destination can be robustly demonstrated by a trusted trader, it will pay the UK tariff if it is destined for the UK and the EU tariff if it is destined for the EU. This is most likely to be relevant to finished goods; and

b. where a good reaches the UK border and the destination cannot be robustly demonstrated at the point of import, it will pay the higher of the UK or EU tariff. Where the good’s destination is later identified to be a lower tariff jurisdiction, it would be eligible for a repayment from the UK Government equal to the difference between the two tariffs. This is most likely to be relevant to intermediate goods. Under the UK’s proposals, it is estimated up to 96 per cent of UK goods trade would be most likely to be able to pay the correct or no tariff upfront, with the remainder most likely to use the repayment mechanism. [footnote 6]

17. The UK recognises that this approach would need to be consistent with the integrity of the EU’s Customs Union and that the EU would need to be confident that goods cannot enter its customs territory without the correct tariff and trade policy being applied. The UK therefore proposes a range of areas for discussion with the EU.

a. The UK and the EU should agree a mechanism for the remittance of relevant tariff revenue. On the basis that this is likely to be the most robust approach, the UK proposes a tariff revenue formula, taking account of goods destined for the UK entering via the EU and goods destined for the EU entering via the UK. However, the UK is not proposing that the EU applies the UK’s tariffs and trade policy at its border for goods intended for the UK. The UK and the EU will need to agree mechanisms, including institutional oversight, for ensuring that this process is resilient and verifiable.

b. The UK and the EU should agree a new trusted trader scheme to allow firms to pay the correct tariff at the UK border without needing to engage with the repayment mechanism. This is most likely to be relevant to finished goods.

c. The UK and the EU should agree the circumstances in which repayments can be granted, which is most likely to be relevant to intermediate goods. To support UK and EU businesses, particularly smaller businesses, the UK proposes that repayment should occur as soon as possible in the supply chain – for example, at the point at which the good is substantially transformed into a UK product, rather than at the point of final consumption. The UK proposes to explore an approach with the EU using existing concepts such as those within the Regional Convention on pan-Euro-Mediterranean preferential rules of origin. The UK recognises that the rules and processes governing eligibility for repayment, including risk profiling and effectively targeted audit and assurance activity, must be sufficiently robust to ensure the mechanism cannot be used to improperly evade EU or UK tariffs and duties, through methods such as re-exporting of goods from the UK to the EU, or vice versa.

d. The UK would maintain a common rulebook with the EU, including the Union Customs Code and rules related to safety and security, and would apply and interpret those rules consistently with the EU. The UK already applies the Union Customs Code, and the new Customs Declarations Service (CDS), due for implementation by 2019, is fully compatible with it.

e. There will need to be appropriate mechanisms for the UK to implement new rules related to customs with the EU, to provide for the proper functioning of the arrangement. There will need to be mechanisms to ensure that rules are applied appropriately, interpreted and enforced consistently, and that disputes between the UK and the EU related to those rules are resolved effectively. Further detail is set out in chapter 4.

18. To ensure that new declarations and border checks between the UK and the EU do not need to be introduced for VAT and Excise purposes, the UK proposes the application of common cross-border processes and procedures for VAT and Excise, as well as some administrative cooperation and information exchange to underpin risk-based enforcement. These common processes and procedures should apply to the trade in goods, small parcels and to individuals travelling with goods (including alcohol and tobacco) for personal use.

19. The UK is seeking to be at the cutting edge of global customs policy. In addition to the mechanisms set out above, the UK also proposes a range of unilateral and bilateral facilitations, to reduce frictions for UK trade with the rest of the world, and promote the greatest possible trade. In particular, the UK will look to:

a. accede to the Common Transit Convention: the UK has already begun the application process for accession;

b. agree mutual recognition of Authorised Economic Operators (AEOs);

c. introduce a range of simplifications for businesses, including implementing self‑assessment over time to allow traders to calculate their own customs duties and aggregate their customs declarations;

d. speed up authorisations processes, for example through increased automation and better use of data; and

e. make existing simplified procedures easier for traders to access.

20. The FCA is designed to ensure that the repayment mechanism is only needed in a limited proportion of UK trade, and to make it as simple as possible to use for those who need to use it. The UK will take into account the views of third countries, to ensure that the UK’s tariff offer is as valuable to them as possible and to continue to explore options to use future advancements in technology to streamline the process. This could include looking to make it easier to allow traders to lodge information in one place. This could include exploring how machine learning and artificial intelligence could allow traders to automate the collection and submission of data required for customs declarations. This could also include exploring how allowing data sharing across borders, including potentially the storing of the entire chain of transactions for each goods consignment, while enabling that data to be shared securely between traders and across relevant government departments, could reduce the need for repeated input of the same data, and help to combat import and export fraud.

21. There will need to be a phased approach to implementation of this model, which the UK and the EU will need to agree through discussions on the future economic partnership.

10.2 1.2.2 Tariffs and rules of origin

22. A necessary underpinning of a UK-EU free trade area, in addition to the FCA, would be an agreement not to impose tariffs, quotas or routine requirements for rules of origin on any UK-EU trade in goods. This would recognise that goods coming into the UK would have faced the same treatment at the border as goods coming into EU Member States, so there would be no need for further restrictions between the UK and the EU.

23. To ensure the trade in goods between the UK and the EU remains frictionless at the border, the UK proposes:

a. zero tariffs across goods (including manufactured goods, agricultural, food and fisheries products), with no quotas;

b. no routine requirements for rules of origin between the UK and EU; and

c. arrangements that facilitate cumulation with current and future Free Trade Agreement (FTA) partners with a view to preserving existing global supply chains. This would allow EU content to count as local content in UK exports to its FTA partners for rules of origin purposes, and UK content to count as local content in EU exports to its FTA partners. Diagonal cumulation would allow UK, EU and FTA partner content to be considered interchangeable in trilateral trade.

10.3 1.2.3 Manufactured goods

24. The UK and the EU are both home to strong manufacturing sectors such as automotives, aerospace, chemicals, electronics, machinery and pharmaceuticals. The production of manufactured goods rarely takes place in one location, with modern manufacturing seeing increasingly specialised firms, with complex supply chains that stretch across multiple countries and operate on a ‘just-in-time’ basis. Both the UK and the EU will want to ensure that European manufacturing continues to thrive in an increasingly competitive global market.

25. The UK’s proposal for a common rulebook would underpin the free trade area for goods. It would cover only those rules necessary to provide for frictionless trade at the border. In the case of manufactured goods, this encompasses all rules that could be checked at the border, as they set the requirements for placing manufactured goods on the market, and includes those which set environmental requirements for products, such as their energy consumption. Certainty around a common rulebook would be necessary to reassure the UK and the EU that goods in circulation in their respective markets meet the necessary regulatory requirements, removing the need to undertake regulatory checks at the border. It would also ensure interoperability between UK and EU supply chains, and avoid the need for manufacturers to run separate production lines for each market. As now, UK firms would be able to manufacture products for export that meet the regulatory requirements of third countries.

26. A common rulebook for manufactured goods is in the UK’s interests. It reflects the role the UK has had in shaping the EU’s rules throughout its membership, as well as the interests of its manufacturers, and the relative stability of the manufactured goods acquis. The UK would also seek participation – as an active participant, albeit without voting rights – in EU technical committees that have a role in designing and implementing rules that form part of the common rulebook. This should ensure that UK regulators could continue to contribute their expertise and capability to EU agencies, including preparing expert opinions that facilitate decisions about individual products.

27. The UK has long advocated a convergence of rules and standards for goods, whether as a member of the EU or on the global stage. The adoption of a common rulebook means that the British Standards Institution (BSI) would retain its ability to apply the “single standard model” – so that where a voluntary European standard is used to support EU rules, the BSI could not put forward any competing national standards. This would ensure consistency between UK and EU standards wherever this type of standard is adopted, with input from businesses, by the European Standards Organisations (ESOs). It would ensure consumers do not face multiple standards for the same products. It would also enable the UK to continue playing a leading role in the ESOs, and with the EU on a global stage, for example in the International Organization on Standardization (ISO), to ensure that there is greater convergence at the international level.

28. In the context of a common rulebook, the UK believes that manufacturers should only need to undergo one series of tests in either market, in order to place products in both markets. This would be supported by arrangements covering all relevant compliance activity, supplemented by continued UK participation in agencies for highly regulated sectors including for medicines, chemicals and aerospace. This would be underpinned by strong reciprocal commitments to open and fair trade and a robust institutional framework.

29. In order to achieve this, the UK’s proposal would cover all of the compliance activity necessary for products to be sold in the UK and EU markets. This includes:

a. testing products to see if they conform to requirements, including conformity assessments and type approval for vehicles, as well as other tests and declarations. It would also apply to labels and marks applied to show they meet the regulatory requirements;

b. accreditation of conformity assessment bodies – testing the testers within a jointly agreed accreditation framework, to provide mutual reassurance that UK and EU conformity assessments are robust;

c. manufacturing and quality assurance processes, such as Good Laboratory Practice and Good Manufacturing Practice, which ensure production methods are being respected, and that declarations are made during manufacturing;

d. the role of nominated individuals, such as the “responsible persons” for certain high-risk products, who interact with authorities or perform a specific role during and after production;

e. bespoke provisions for human and animal medicines which reflect their unique status, including the release of individual batches by a qualified person based in the UK or EU, and the role of the qualified person for pharmacovigilance, responsible for ongoing safety monitoring of potential side effects; and

f. licensing regimes and arrangements, such as export licenses, for the movement of restricted products.

Example: mutual recognition of Vehicle Type Approvals

The common rulebook would include the type approval system for all categories of motor vehicles. The UK and the EU would continue recognising the activities of one another’s type approval authorities, including whole vehicle type approval certificates, assessments of conformity of production procedures and other associated activities. Member State approval authorities would continue to be permitted to designate technical service providers in the UK for the purpose of EC approvals and vice versa.

Both the UK and the EU would continue to permit vehicles to enter into service on the basis of a valid certificate of conformity. Once in production, the UK and the EU would continue to recognise the ongoing role of type approval authorities, including monitoring of a manufacturer’s conformity of production procedures and issuing any extensions or revisions to existing type approval certificates. UK and EU type approval authorities would continue to uphold their current obligations, including working closely with other authorities to identify non-conformities and ensure appropriate action is taken to rectify them.

30. In some manufactured goods sectors where more complex products have the potential to pose a higher risk to consumers, patients or environmental safety, a greater level of regulatory control is applied. The European Medicines Agency (EMA), the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) facilitate part of these regulatory frameworks. In line with the UK’s objective of ensuring that products only go through one approval mechanism to access both markets, the UK is seeking participation in these EU agencies, as an active participant, albeit without voting rights, which would involve making an appropriate financial contribution. The UK would want to secure access to relevant IT systems, ensuring the timely transfer of data between UK and EU authorities. In addition, it would seek:

a. for EASA, becoming a third country member via the established route under Article 66 of the EASA basic regulation, as Switzerland has;

b. for ECHA, ensuring UK businesses could continue to register chemical substances directly, rather than working through an EU-based representative; and

c. for the EMA, ensuring that all the current routes to market for human and animal medicine remain available, with UK regulators still able to conduct technical work, including acting as a ‘leading authority’ for the assessment of medicines, and participating in other activities like ongoing safety monitoring and the incoming clinical trials framework.

31. To ensure that there is no market disruption as the UK and the EU transition from the implementation period to this new free trade area, the UK proposes that all manufactured goods authorisations, approvals, certifications, and any agency activity undertaken under EU law (for example, to register a chemical), completed before the end of the implementation period, should continue to be recognised as valid in both the UK and the EU. Moreover, any such processes underway as the UK and the EU transition from the implementation period should be completed under existing rules, with the outcomes respected in full.

10.4 1.2.4 Agriculture, food and fisheries products

32. There is extensive trade between the UK and the EU in agriculture (food, feed and drink) products and the EU is the UK’s single largest trade partner.[footnote 7] 70 per cent of UK agri-food imports came from the EU in 2017. [footnote 8] Food and drink manufacturing is the UK’s largest manufacturing sector, contributing £27.8 billion in Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2017. [footnote 9] Much like manufactured goods, the agri-food sector relies on complex international supply chains.

33. Under the existing constitutional settlements in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, each devolved administration and legislature generally has competence to make its own primary and secondary legislation in relation to agriculture, as well as in related areas such as animal health and welfare, food safety, plant health and fisheries. The UK Government will work closely with the devolved administrations, who share high ambitions for a sustainable agricultural industry in the UK, as the UK withdraws from the EU, and will ensure future arrangements within the UK work for the whole of the UK.

34. There are three broad categories of rules that apply to agriculture, food and fisheries products:

a. those that must be checked at the border, including relevant Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) rules, which safeguard human, animal and plant health;

b. those relating to wider food policy, such as marketing rules that determine how agri-food products can be described and labelled, which do not need to be checked at the border; and

c. those relating to domestic production, such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP).

35. The UK’s proposal for a common rulebook on agri-food encompasses those rules that must be checked at the border. The UK and the EU have set the global standard for the protection of human, animal and plant health, and both have set an ambition to maintain high standards in the future. As for manufactured goods, certainty around a common rulebook is necessary to reassure the UK and the EU that agri-food products in circulation in their respective markets meet the necessary regulatory requirements. This would remove the need to undertake additional regulatory checks at the border – avoiding the need for any physical infrastructure, such as Border Inspection Posts, at the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland. A common rulebook would also protect integrated supply chains, trade between the UK and the EU, and consumers and biosecurity.

36. There are wider food policy rules that set marketing and labelling requirements. It is not necessary to check these rules are met at the border, because they do not govern the way in which products are produced, but instead determine how they are presented to consumers. These rules are most effectively enforced on the market, and as such it is not necessary to incorporate them into the common rulebook. Indeed there are differences between Member States currently on aspects of food policy, for example food labelling. Tailoring the regulatory environment to best suit businesses operating in the local market is better for consumers, businesses and the environment. The UK will tailor its food policy to better reflect business needs, improve value for money and support innovation and creativity.

37. For these rules, there are existing precedents of equivalence agreements covering testing and approval procedures. For example, the EU has reciprocal equivalence arrangements or agreements for organic production rules and control systems with a number of countries: Canada, Chile, Israel, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Tunisia, the US and New Zealand. The UK wants equivalence arrangements on wider food policy rules. The UK has high standards in place on food policy, including areas of UK leadership such as unfair trading practices.

38. Included in the remit of wider food policy rules are the specific protections given to some agri-food products, such as Geographical Indications (GIs). GIs recognise the heritage and provenance of products which have a strong traditional or cultural connection to a particular place. They provide registered products with legal protection against imitation, and protect consumers from being misled about the quality or geographical origin of goods. Significant GI-protected products from the UK include Scotch whisky, Scottish farmed salmon, and Welsh beef and lamb.

39. The UK will be establishing its own GI scheme after exit, consistent with the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS). This new UK framework will go beyond the requirements of TRIPS, and will provide a clear and simple set of rules on GIs, and continuous protection for UK GIs in the UK. The scheme will be open to new applications, from both UK and non-UK applicants, from the day it enters into force.

40. The UK will be leaving the CFP and CAP: these and other areas of domestic production are not relevant to the UK’s and the EU’s trading relationship, and so would not be captured by the common rulebook or any form of regulatory equivalence. The EU’s view at the WTO is that direct payments under CAP are not market distorting – and the EU has deep relationships on fisheries with the other North Sea countries on the basis of annual negotiations. The UK will be free to design agricultural support policies that deliver the outcomes most relevant to its market, within the confines of WTO rules. The UK has been clear that it will seek to improve agricultural productivity and deliver improved environmental outcomes through its replacement for CAP. Similarly, on the CFP, the UK will be an independent coastal state, able to control access to its waters and the allocation of fishing opportunities. The UK’s proposals for fisheries are covered in chapter 3.

41. By being outside the CAP, and having a common rulebook that only applies to rules that must be checked at the border, the UK would be able to have control over new future subsidy arrangements, control over market surveillance of domestic policy arrangements, an ability to change tariffs and quotas in the future, and the freedom to apply higher animal welfare standards that would not have a bearing on the functioning of the free trade area for goods – such as welfare in transport and the treatment of live animal exports.

42. In acknowledging the specific situation in respect of Northern Ireland and Ireland, all North-South cooperation on agriculture flowing from the Belfast (‘Good Friday’) Agreement has been mapped in detail through the joint mapping exercise conducted in Phase 1, and will be protected in full. Northern Ireland and Ireland form a single epidemiological unit. The UK is fully committed to ensuring that the Northern Ireland Executive and North South Ministerial Council can, through agreement, continue to pursue specific initiatives, such as the All Ireland Animal Health and Welfare Strategy.

10.5 1.2.5 Market surveillance

43. As now, all products that enter the UK market will need to comply with the UK’s regulations and standards. The new free trade area for goods, including agri-food, would need to be supported by robust domestic market surveillance and cooperation, to ensure that rules are upheld in both markets.

44. Following its withdrawal from the EU, the UK intends to maintain its robust programme of risk-based market surveillance to ensure that dangerous products do not reach consumers. This includes the ability to intercept products as they enter the UK, check products already on the market, and gather information through a variety of intelligence sources.

45. UK regulators propose establishing cooperation arrangements with EU regulators to ensure that authorities on both sides can take appropriate, consistent and coordinated action to prevent non-compliant products from reaching consumers or patients, or harming the environment. This should be complemented by the exchange of intelligence, including information received directly from businesses and consumers, and reporting mechanisms.

46. In order to support these cooperation arrangements, the UK is seeking access to the EU’s communications systems, such as the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF), Rapid Alert System for Serious Risk (Rapex), and the Information and Communication System for Market Surveillance (ICSMS). This would ensure that UK and EU authorities could issue alerts to one another to respond in an effective and timely manner when they had identified unsafe or non-compliant products.

11. 1.3 Services and investment

47. The UK is world leading in many services sectors, including legal, business and financial services. In 2017, services made up 79 per cent of total UK GVA worth £1.46 trillion. [footnote 10] In 2017, 21 per cent of EU27 services imports came from the UK, and 20 per cent of EU27 services exports went to the UK. [footnote 11] Globally services trade is growing rapidly; UK services trade with non-EU countries grew by 73 per cent between 2007 and 2017. [footnote 12]

48. The UK is proposing new arrangements for services and digital that would provide regulatory flexibility, which is important for the UK’s services-based economy. This means that the UK and the EU will not have current levels of access to each other’s markets.

49. The UK’s proposal builds on the principles of international trade and the precedents of existing EU trade agreements, and reflects its unique starting point. It would include:

a. general provisions that minimise the introduction of discriminatory and non‑discriminatory barriers to establishment, investment and the cross-border provision of services, with barriers only permitted where that is agreed upfront;

b. a system for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications, enabling professionals to provide services across the UK and EU;

c. additional, mutually beneficial arrangements for professional and business services; and

d. a new economic and regulatory arrangement for financial services.

11.1 1.3.1 General provisions

50. The WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) provides a framework for global services trade and defines four modes of services supply:

a. a service crossing a border (for example, a service being provided over the telephone);

b. a consumer of a service crossing a border (for example, tourism);

c. a service provider establishing a legal presence across a border (for example, a retail chain opening a new establishment in another country); and

d. a service provider crossing a border to a consumer (for example, a lawyer going to another country to provide legal advice to a client).

51. Under GATS, FTAs are obliged to cover all modes of services supply and to have substantial sectoral coverage. But each new FTA is unique to the parties involved, giving service providers different market access rights. Over time FTAs have promoted a more liberalising approach to services trade.

52. The UK proposes arrangements with broad coverage, ensuring that service suppliers and investors are allowed to operate in a broad number of sectors without encountering unjustified barriers or discrimination unless otherwise agreed. Specifically, the UK is seeking:

a. broad coverage across services sectors and the modes of supply, in line with GATS obligations;

b. deep Market Access commitments, eliminating, among other things, explicit restrictions on the number of services providers from one country that can operate in another;

c. deep commitments on National Treatment, to guarantee that foreign service providers are treated the same as equivalent local providers, with any exceptions kept to a minimum;

d. provisions to ensure the free and timely flow of financial capital for day-to-day business needs, including payments and transfers; and

e. best-in-class arrangements on domestic regulation, which ensure that all new regulation is necessary and proportionate.

11.2 1.3.2 Mutual recognition of professional qualifications

53. The EU regime for the recognition of professional qualifications enables UK and EU professionals to practise across both the UK and the EU on a temporary, longer-term or permanent basis, without fully having to retrain or requalify. Since 1997 the UK has recognised over 142,000 EU qualifications, including for lawyers, social workers and engineers. [footnote 13] Over 27,000 decisions to recognise UK qualifications have been undertaken in the EU.[footnote 14]

54. The UK agrees with the position set out in the European Council’s March 2018 Guidelines, which stated that the future partnership should include ambitious provisions on the recognition of professional qualifications. This is particularly relevant for the healthcare, education and veterinary/agri-food sectors in the context of North-South cooperation between Northern Ireland and Ireland.

55. The UK’s arrangements with the EU should not be constrained by existing EU FTA precedents. CETA includes some of the EU’s most ambitious third country arrangements on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications. Yet CETA only sets a framework within which regulators may negotiate recognition agreements for professional qualifications; it does not itself provide for mutual recognition. The UK proposes establishing a system that:

a. is broad in scope, covering the same range of professions as the Mutual Recognition of Qualifications Directive;

b. includes those operating either on a permanent or temporary basis across borders;

c. is predictable and proportionate, enabling professionals to demonstrate that they meet the necessary requirements, or to undertake legitimate compensatory measures where there is a significant difference between qualifications or training, in a timely way; and

d. provides transparency, with cooperation between regulators to facilitate the exchange of information about breaches of professional standards, and to review changes to professional qualifications over time.

11.3 1.3.3 Professional and business services

56. The UK and EU economies rely on the cross-border provision of professional services. This includes legal services, where the UK is the destination for 14.5 per cent of total EU legal services exports. [footnote 15] It also includes accounting and audit services. In 2016, UK firms provided over 14 per cent of EU27 audit and accountancy imports. [footnote 16]

57. In addition to the general services provisions, the UK proposes supplementary provisions for professional and business services, for example, permitting joint practice between UK and EU lawyers, and continued joint UK-EU ownership of accounting firms. The supplementary provisions would not replicate Single Market membership, and professional and business service providers would have rights in the UK and the EU which differ from current arrangements.

11.4 1.3.4 Financial services

58. The UK and EU financial services markets are highly interconnected: UK-located banks underwrite around half of the debt and equity issued by EU businesses;[footnote 17] UK‑located banks are counterparty to over half of the over-the-counter interest rate derivatives traded by EU companies and banks; [footnote 18] around £1.4 trillion of assets are managed in the UK on behalf of European clients; [footnote 19] the world-leading London Market for insurance hosts all of the world’s twenty largest international (re)insurance companies; and more international banking activity is booked in the UK than in any other country. This interconnected market has benefits for consumers and businesses across Europe. For example, one study has found that if new regulatory barriers forced the fragmentation of firms’ balance sheets, the wholesale banking industry would need to find £23-38 billion of extra capital.[footnote 20] These are costs that would ultimately be borne by consumers and businesses.

59. This interconnectedness also highlights the UK’s and the EU’s shared interest in financial stability. The UK is host to all 30 global systemically important banks and is the home regulator for four of them. Given its scale, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has described financial stability in the UK as a “global public good”. [footnote 21] Alongside its European partners, the UK has developed an institutional framework to manage financial stability while ensuring the regulatory system supports a global financial centre.

60. As the UK leaves the EU and the Single Market, it recognises the need for a new and fair balance of rights and responsibilities. The UK can no longer operate under the EU’s “passporting” regime, as this is intrinsic to the Single Market of which it will no longer be a member.

61. In addition, given the importance of financial services to financial stability, both the UK and the EU will wish to maintain autonomy of decision-making and the ability to legislate for their own interests. For example, in some cases, the UK will need to be able to impose higher than global standards to manage its financial stability exposure. In other areas, the UK market contains products and business models that are different to those found elsewhere in the EU, and regulation would need to reflect these differences. The decision on whether and on what terms the UK should have access to the EU’s markets will be a matter for the EU, and vice versa. However, a coordinated approach leading to compatible regulation is also essential for promoting financial stability and avoiding regulatory arbitrage.

62. The EU has third country equivalence regimes which provide limited access for some of its third country partners to some areas of EU financial services markets. These regimes are not sufficient to deal with a third country whose financial markets are as deeply interconnected with the EU’s as those of the UK are. In particular, the existing regimes do not provide for:

a. institutional dialogue, meaning there is no bilateral mechanism for the EU and the third country to discuss changes to their rules on financial services in order to maximise the chance of maintaining compatible rules, and to minimise the risks of regulatory arbitrage or threats to financial stability;

b. a mediated solution where equivalence is threatened by a divergence of rules or supervisory practices;

c. sufficient tools for reciprocal supervisory cooperation, information sharing, crisis procedures, or the supervision of cross-border financial market infrastructure;

d. some services, where clients in the UK and the EU currently benefit from integrated markets and cross-border business models. This would lead to unnecessary fragmentation of markets and increased costs to consumers and businesses; or

e. phased adjustments and careful management of the impacts of change, so that businesses face a predictable environment.

63. In this context, the UK proposes a new economic and regulatory arrangement with the EU in financial services. This would maintain the economic benefits of cross‑border provision of the most important international financial services traded between the UK and the EU – those that generate the greatest economies of scale and scope – while preserving regulatory and supervisory cooperation, and maintaining financial stability, market integrity and consumer protection.

64. This new economic and regulatory arrangement would be based on the principle of autonomy for each party over decisions regarding access to its market, with a bilateral framework of treaty-based commitments to underpin the operation of the relationship, ensure transparency and stability, and promote cooperation. Such an arrangement would respect the regulatory autonomy of both parties, while ensuring decisions made by either party are implemented in line with agreed processes, and that provision is made for necessary consultation and collaboration between the parties.

65. As part of this, the existing autonomous frameworks for equivalence would need to be expanded, to reflect the fact that equivalence as it exists today is not sufficient in scope for the breadth of the interconnectedness of UK-EU financial services provision. A new arrangement would need to encompass a broader range of cross‑border activities that reflect global financial business models and the high degree of economic integration. The UK recognises, however, that this arrangement cannot replicate the EU’s passporting regime.

66. As the UK and the EU start from a position of identical rules and entwined supervisory frameworks, the UK proposes that there should be reciprocal recognition of equivalence under all existing third country regimes, taking effect at the end of the implementation period. This reflects the reality that all relevant criteria, including continued supervisory cooperation, can readily be satisfied by both the UK and the EU. It would also provide initial confidence in the system to firms and markets.

67. Although future determinations of equivalence would be an autonomous matter for each party, the new arrangement should include provisions through the bilateral arrangement for:

a. common principles for the governance of the relationship;

b. extensive supervisory cooperation and regulatory dialogue; and

c. predictable, transparent and robust processes.

Common principles for the governance of the relationship

68. As established in many existing EU provisions, this approach would be based on an evidence-based judgement of the equivalence of outcomes achieved by the respective regulatory and supervisory regimes. The UK and the EU would set out a shared intention to avoid adopting regulations that produce divergent outcomes in relation to cross-border financial services. In practice, as the UK and the EU have since the financial crisis, the UK will continue to be active in shaping international rules, and will continue to uphold global norms. To reflect this, the UK-EU arrangement should include common objectives, such as maintaining economic relations of broad scope, preserving regulatory compatibility, and supporting collaboration – bilaterally and in multilateral fora – to manage shared interests such as financial stability and the prevention of regulatory arbitrage.

Extensive supervisory cooperation and regulatory dialogue

69. The UK proposes that the UK and the EU would commit to an overall framework that supports extensive collaboration and dialogue.

a. Regulatory dialogue: for equivalence to be maintained over the long term, the UK and the EU should be able to understand and comment on each other’s proposals at an early stage through a structured consultative process of dialogue at political and technical level, while respecting the autonomy of each side’s legislative process and decision-making.

b. Supervisory cooperation: in a close economic relationship between the UK and the EU financial services sectors, it would be necessary to ensure close supervisory cooperation in relation to firms which pose a systemic risk and/or that provide significant cross-border services on the basis of equivalence. It will be essential for the UK and the EU to commit to reciprocal and close cooperation to protect consumers, financial stability and market integrity with codified procedures for routine cooperation and for coordination in crisis situations. This should include appropriate reciprocal participation in supervisory colleges, which are coordination structures that bring together regulatory authorities involved in the supervision of banks and other major financial institutions – as well as other supervisory structures, including information exchange, mechanisms for consultation over decisions affecting the other party, and arrangements for the supervision of market infrastructure.

Predictable, transparent and robust processes

70. To give business the certainty necessary to plan and invest, transparent processes would be needed to ensure the relationship is stable, reliable and enduring. The UK envisages that some of these processes would be bilaterally agreed and treaty-based; others would be achieved through the autonomous measures of the parties.

a. Transparent assessment methodology: the process for assessing equivalence should be based on clear and common objectives; make use of consultation with industry and other stakeholders; and include the possibility of using expert panels.

b. Structured withdrawal process: if circumstances arise that cause either party to wish to withdraw equivalence, there should be an initial period of consultation on possible solutions to maintain equivalence. Either party may also indicate to the other that it no longer seeks equivalence in a certain area. There should then be clear timelines and notice periods, which are appropriate for the scale of the change before it takes effect. There should also be a safeguard for acquired rights to avoid risks to financial stability, market integrity or consumer protection from sudden changes to the regulatory environment.

c. Long-term stabilisation: in accordance with WTO principles, there should be a presumption against unilateral changes that narrow the terms of existing market access regimes, other than in exceptional circumstances. This would mean each side trying to avoid future changes that assess equivalence in entirely new ways that could destabilise an established relationship. Existing equivalence decisions should only lapse after a new decision has been taken.

71. Finally, where disputes arise between the UK and the EU on the binding treaty-based commitments, the institutional arrangements set out in further detail in chapter 4 should apply.

12. 1.4 Framework for mobility

72. EU citizens are integral to communities across the UK, with 3.5 million EU citizens living in the UK. [footnote 22] Approximately 800,000 UK nationals play an equally important role in communities across the EU.[footnote 23] The UK and the EU have already reached an agreement on citizens’ rights which provides EU citizens living in the UK and UK nationals living in the EU before the end of the implementation period with certainty about their rights going forward. Individuals will continue to be able to move, live and work on the same basis as now up until the end of December 2020.

12.1 1.4.1 Ending free movement of people

73. In future it will be for the UK Government and Parliament to determine the domestic immigration rules that will apply. Free movement of people will end as the UK leaves the EU. The Immigration Bill will bring EU migration under UK law, enabling the UK to set out its future immigration system in domestic legislation.

74. The UK will design a system that works for all parts of the UK. The Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) report, due in September 2018, will provide important evidence on patterns of EU migration and the role of migration in the wider economy to inform this. Further details of the UK’s future immigration system will be set out in due course.