The Green Book (2022)

Updated 16 May 2024

1. Introduction

The Green Book is guidance issued by HM Treasury on how to appraise policies, programmes and projects. It also provides guidance on the design and use of monitoring and evaluation before, during and after implementation. Appraisal of alternative policy options is an inseparable part of detailed policy development and design. This guidance concerns the provision of objective advice by public servants to decision makers, which in central government means advice to ministers. In arms-length public organisations the decision makers may be appointed board members, and where local authorities are using the method,[footnote 1] elected council members. The guidance is for all public servants concerned with proposals for the use of public resources, not just for analysts. The key specialisms involved in public policy creation and delivery, from policy at a strategic level to analysis, commercial strategy, procurement, finance, and implementation must work together from the outset to deliver best public value. The Treasury’s five case model is the means of developing proposals in a holistic way that optimises the social / public value produced by the use of public resources. Similarly, there is a requirement for all organisations across government to work together, to ensure delivery of joined up public services.

The Green Book is not a mechanical or deterministic decision-making device. It provides approved thinking models and methods to support the provision of advice to clarify the social – or public – welfare costs, benefits, and trade-offs of alternative implementation options for the delivery of policy objectives.

Use of the Green Book should be informed by an understanding of other HM Treasury guidance:

-

Managing Public Money – Which provides guidance on the responsible use of public resources

-

The Business Case Guidance for Programmes – Which provides detailed guidance on the development and approval of capital spending programmes

-

The Business Case Guidance for Projects – Which provides detailed guidance on the development and approval of capital spending projects

-

the Aqua Book – Which sets out standards for analytical modelling and assurance

-

the Magenta Book – Which provides detailed guidance on evaluation methods

-

Supplementary subject guidance explains how the Green Book may be applied when dealing with particular topics, for example greenhouse gas emissions. This should be used where required. A list of topic specific supplementary guidance is given on page 127.

-

Supplementary departmental guidance is produced by Departments and arms-length public organisations. It deals with the application of the Green Book in the particular context that is the organisation’s area of responsibility. This supplementary guidance must be consistent with the Green Book, the Business Case guidance and supplementary guidance on specific topics. When the Green Book is updated supplementary guidance must be realigned as required to ensure consistency across government and the wider public sector.

Green Book guidance applies to all proposals that concern public spending, taxation, changes to regulations, and changes to the use of existing public assets and resources – see Box 1 below.

Box 1. Scope of Green Book Guidance

Green Book guidance covers:

-

policy and programme development

-

all proposals concerning public spending

-

legislative or regulatory proposals

-

sale or use of existing government assets – including financial assets

-

appraisal of a portfolio of programmes and projects

-

structural changes in government organisations

-

taxation and benefit proposals

-

significant public procurement proposals

-

major projects

-

changes to the use of existing public assets and resources

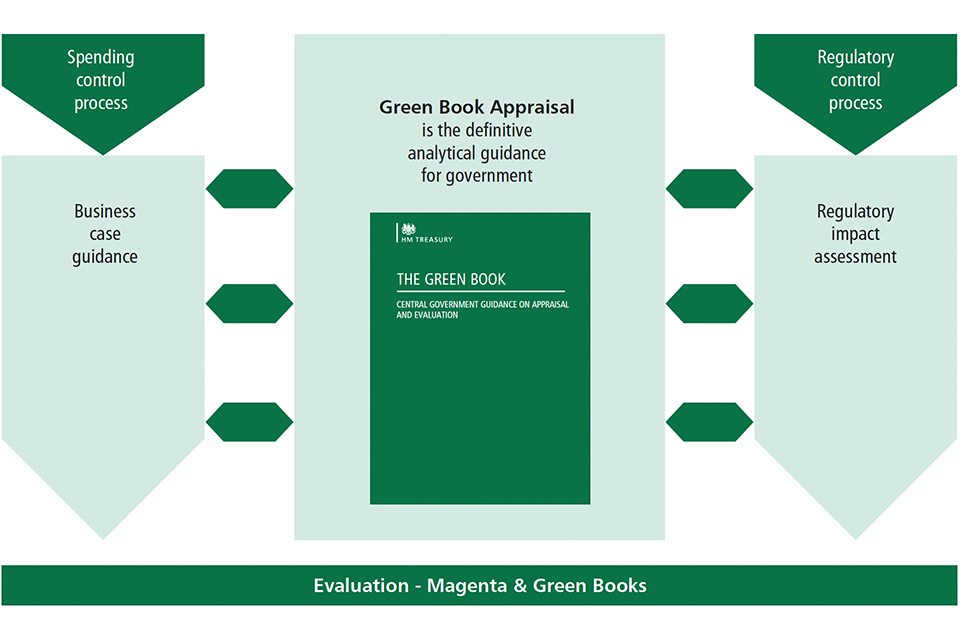

The role of appraisal and evaluation is to provide objective analysis to support decision making. Where the use of significant new and existing public resources is required the proportionate employment of the Green book and its supplementary business case guidance is mandatory. The decision support process includes the scrutiny of business cases by approving bodies in government departments and other public organisations, Treasury Approval Processes and the Regulatory Impact Assessment process. The Five Case Model and the methods and principles of the Green Book should also support options appraisal when formal business cases and regulatory decisions are not required. The relationship between Green Book guidance and government decision making processes is shown in Figure 1.

This guidance should be applied proportionately. The resources and effort employed should be related to costs, benefits and risks involved to society and to the public sector as a result of the proposals under consideration.

Monitoring and evaluation of all proposals should be proportionately included in the budget and the management plan of all significant proposals as an integral part of all proposed interventions.

Figure 1. The Green Book and Appraisal in Context

Figure 1. The Green Book and Appraisal in Context

This guidance has been designed to be accessible to a variety of users – from policy officials to analysts. Accordingly, it follows a tiered structure where:

-

a high-level overview is provided in chapters 1 – 3

-

detailed information for practitioners is provided in chapters 4 – 8

-

technical information and shared valuations for use in appraisal are provided in annexes 1 – 6

-

hyperlinks have been inserted to allow users to cross-reference within the Green Book and associated supplementary guidance

-

The Green Book’s chapters are as follows:

chapter 2 provides a non-technical introduction to appraisal and evaluation

-

chapter 3 provides an overview of how appraisal fits within government decision making processes

-

chapter 4 explains how to generate options and undertake longlist appraisal

-

chapter 5 explains how to undertake detailed appraisal of a shortlist of options using social cost benefit and social cost effectiveness approaches, and distributional and sensitivity analysis and accounting for unquantifiable factors it provides the Green Book definition of public/social value for money

-

chapter 6 sets out the approach to valuation of costs and benefits

-

chapter 7 sets out how to present appraisal results

-

chapter 8 sets out the approach to monitoring and evaluation

-

annexes 1 – 7 provide further technical appraisal information and values for use in appraisal across government

1.1 Scope and relationship with other appraisal guidance

The content and boundary of all Green Book guidance is determined by HM Treasury. The content is peer reviewed by the Government Chief Economists Appraisal Group. It applies to all government departments, arm’s length public bodies with responsibility derived from central government for public funds and regulatory authorities.

Departments also produce internal guidance, setting out how Green Book appraisal should be carried out for their areas of responsibility. For consistency, departmental guidance should align with the Green Book. Where departmental guidance affects other government departments, or contains significant developments in methods and approach, it should be agreed with HM Treasury and its content subjected to peer review by the Government Chief Economist Appraisal Group. All new supplementary and departmental guidance should from its inception, be developed in consultation with HM Treasury and subject to the same peer review process.

Throughout the guidance there are links to external supplementary guidance. These provide further detail on subjects that are relevant across government e.g. the valuation of greenhouse gas emissions. To provide background and support understanding, non-governmental research and discussion papers are referenced in the Green Book. These documents do not form part of the guidance.

2. Introduction to Appraisal and Evaluation

This chapter provides a non-technical introduction to appraisal and evaluation.

2.1 Principles of appraisal

Appraisal is the process of assessing the costs, benefits and risks of alternative ways to meet government objectives. It helps decision makers to understand the potential effects, trade-offs and overall impact of options by providing an objective evidence base for decision making.

Appraisal The appraisal of social value, also known as public value, is based on the principles and ideas of welfare economics and concerns overall social welfare efficiency, not simply economic market efficiency. Social or public value therefore includes all significant costs and benefits that affect the welfare and wellbeing of the population, not just market effects. For example, environmental, cultural, health, social care, justice and security effects are included. This welfare and wellbeing consideration applies to the entire population that is served by the government, not simply taxpayers. A summary outline of the key steps in appraisal is shown below in Box 2.

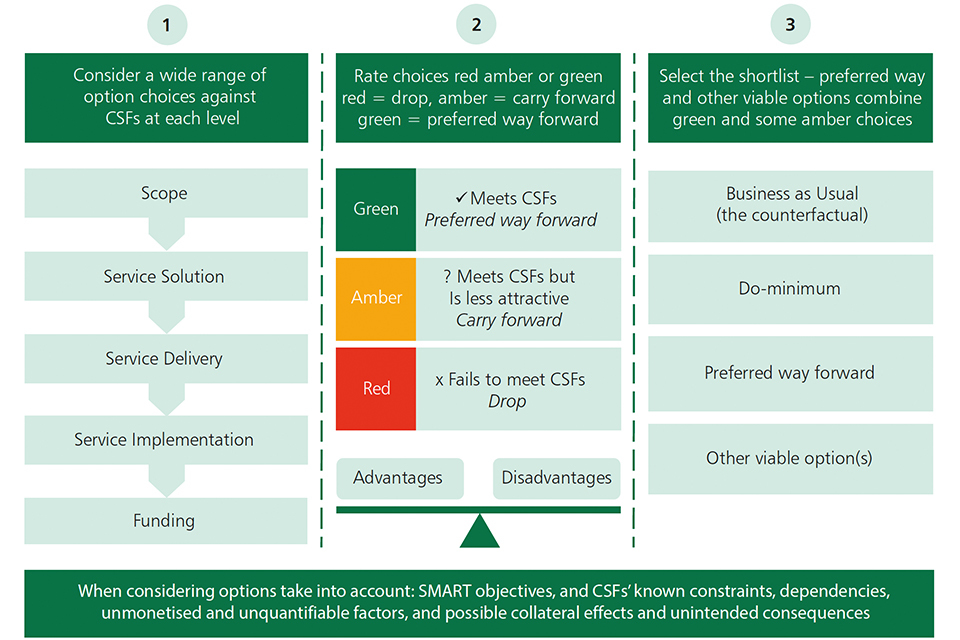

The first step in appraisal is to provide the rationale for intervention, a process covered more fully in chapters 2 to 4 and in the business case guidance. Appraisal is a two-stage process, the first stage of which is the consideration of a longlist of option choices and the selection of a rational and viable set of options for shortlist analysis. The options framework and filter process used for longlist analysis and shortlist selection is explained in Chapter 4. The second stage in appraisal is shortlist analysis using social cost benefit analysis (CBA) or social cost effectiveness analysis is explained in Chapter 5.

In government as in many large private sector organisations, major changes involve a sequence of decisions at several levels. Typically, organisations will have their high level purpose expressed in some form of mission statement and may even talk about their intentions in terms of a vision. To make these rather high level statements into implementable programmes and projects, there needs to be another level of more specific strategic policy objectives. Realisation of these strategic objectives requires the organisation and planning of programmes and projects which are best managed in related strategic portfolios. Policies provide direction and high level objectives, these enduring parameters drive and direct the required changes the organisation is working to bring about. The definitions of key terms used in this guidance are given in Box 3.

At each level of decision making, objectives are set so that the proposal being considered meets the needs placed upon it by a preceding, higher level proposal. For example, a programme to deliver signalling for a new railway line will be part of a wider programme to construct the fixed infrastructure the line requires. The signalling system will need to meet the requirements of both the rail infrastructure plan, and the operational needs of the new line, so that it enables safe running of planned train speeds and frequency. Individual projects within the signalling programme will each deliver a component of the overall system, and need to be understood in that context.

Box 2. Summary Outline of Key Appraisal Steps

-

Preparing the Strategic case which includes the Strategic Assessment and Making the Case for Change,[footnote 2] quantifies the present situation and Business as Usual (the BAU) and identifies the SMART objectives. This Rationale is the vital first step in defining what is to be appraised. Delivery of the SMART objectives must drive the rest of the process across all dimensions of the Five Case Model as explained throughout this guidance.

-

Longlist analysis using the options framework filter considers how best to achieve the SMART objectives. Alternative options are viewed through the lens of public service provision to avoid bias towards preconceived solutions that have not been rigorously tested. A wide range of possibilities are considered, and a viable shortlist is selected including a preferred way forward. These are carried forward for further detailed appraisal. This process is where all complex issues are taken into account and is the key to development of optimum Value for Money proposals likely to deliver reasonably close to expectations.

-

Shortlist appraisal follows and is at the heart of detailed appraisal, where expected costs and benefits are estimated, and trade-offs are considered. This analysis is intimately interconnected to the, Strategic, Commercial, Financial, and Management dimensions of the five case model, none of which can be developed or appraised in isolation. The use of Social Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) or Social Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) are the means by which cost, and benefit trade-offs, are considered.

-

Identification of the preferred option is based on the detailed analysis at the shortlist appraisal stage. It involves determining which option provides the best balance of costs, benefits, risks and unmonetisable factors thus optimising value for money.

-

Monitoring is the collection of data, both during and after implementation to improve current and future decision making.

-

Evaluation is the systematic assessment of an intervention’s design, implementation and outcomes. Both monitoring and evaluation should be considered before, during and after implementation.

Box 3. The meanings of widely used words as they are used in the Green Book

A Policy is a statement of intent that is implemented through a procedure or a protocol and a deliberate system of principles to guide decisions and achieve rational outcomes. Policy provides the enduring parameters to police change. As well as setting strategic policy objectives it consists of all the elements below.

Strategy is a plan of action designed to achieve an overall aim or objective. Derived originally from the art of planning and directing overall military operations and movements in a war or battle.

A Strategic Portfolio consists of the programmes and projects necessary to make the changes required to deliver a strategic objective or objectives that contribute to delivery of policy.

A Programme is an interrelated series of Sub-Programmes, Projects and related activities in pursuit of an organisation’s longer-term objectives. Programmes deliver outcomes through changes in services

A Project is a temporary organisation designed to produce a specific predefined output at a specified time using predetermined resources.

In a similar way, the government’s priorities are expressed in high level strategic objectives. To make them implementable these then drive the creation of strategic portfolios. These portfolios consist of the programmes and projects that are required to realise a strategic policy objective. Programmes identify and manage the interrelated projects and sub-programmes needed. In this example improved transportation services are a means to change economic and social outcomes. The required projects deliver changes in outputs, which when taken together support delivery of a change in rail service provision.

The changes in services in the above example are expected to result in changes in economic and social outcomes. At each level of decision making the application of appraisal takes account of the wider context of which the proposal is a part. Appraisal should be proportionate to the costs and risks involved to both the public sector and to the public i.e. to society. The levels at which decisions occur are explained in more detail in Chapter 3.

2.2 Rationale

It is necessary to set out clearly the purpose of the intervention. This is known as the rationale, and in central government overall policy objectives are determined by ministers or other decision makers. Officials should identify and design alternative options to achieve these stated objectives. Advice must be based on objective analysis and real options.

The rationale should explain how intended changes in outcomes will be produced by the recommended delivery options. The objective of the proposal may be to:

-

maintain service continuity arising from the need to replace some factor in the existing delivery process or

-

to improve the efficiency of service provision

-

to increase the quantity or improve the quality of a service

-

to provide a new service

-

to comply with regulatory changes

-

often a mix of all of all of these.

It is however vitally necessary to be clear that the rationale may also be to improve the welfare efficiency of existing private sector markets, for example by making polluting organisations maintain standards and meet the cost of remediation to retain standards. It may also concern achievement of ethical distributional objectives for example fair access to health or education. It might involve providing social/public goods that are not provided at a satisfactory level by the market alone, for example justice services or social services.

2.3 Generating Options and longlist appraisal

Proposals should initially be considered from the perspective of the service needed to deliver the required policy outcome and not from the perspective of a preconceived solution or asset creation. This guards against thinking too narrowly or being trapped by preconceptions into missing optimum solutions.

Longlist analysis and selection of the shortlist must use the options [footnote 3] in a workshop that including key experts and stakeholders as explained in more detail in Chapter 4. This method brings together the results of research, advice of experts, and knowledge of stakeholders. Provided the preparatory research has been carried out, and the right experts and stakeholders involved in the workshop, a wide variety of service scope, solution methods, service delivery methods, service implementation designs, and service funding options can be relatively rapidly appraised. Unintended collateral effects should also be considered including distributional effects that may unfairly impact particular parts of the UK, or groups within UK society. The reasons for inclusion or exclusion of option choices in the shortlist must be transparently recorded and cross referenced as a key part of longlist appraisal.

Where relevant place based effects, and the duties placed on public officials by the Equality Act 2010 and effects on families’ when applying the family test 2010 and significant income distribution effects must be included proportionately in appraisal as set out in this guidance. Where they are not relevant a short explanation of why must be provided.

2.4 Shortlist appraisal

Shortlist appraisal is where the expected costs and benefits of an intervention are estimated, including the cost of risks and risk management, it is where the trade-off between them is considered. Where there is a clear difference in the social costs and benefits between alternative shortlisted options Social Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) is used. Where there is no measurable social difference between options then Social Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) is appropriate. Both of these are explained in more detail in Chapter 5.

Costs and benefits are viewed from the perspective of UK society, not just to the public sector or originating institution. That is not to say for example that a proposal to improve provision of acute care by extending an NHS building would search for UK wide effects, but simply to say that it would be considered from the perspective of the local health economy, and not confine itself to effects on the organisation making the proposal. This common sense approach to costs and benefits is not confined to thinking about branches of public services in isolation. Services provided to the public by central and local government are experienced by the public as a flow of services and there is an understandable and undeniable expectation that the various arms of government are joined up and will deliver optimum joined up public services. This understanding must inform the design of proposals in general and the choice of costs and benefits used in appraisal.

Assessing costs and benefits across all affected groups or places matters because even a proposal with a relatively low public sector cost such as a new regulation, may have significant effects on specific groups in society, places or businesses. Costs or benefits of options should be valued and monetised where possible in order to provide a common metric.

Where there is no reasonable market price a range of valuation techniques are recommended. These include societal costs and benefits such as environmental values, and they are explained further in Chapters 5 and 6 with more technical guidance in the Annexes. In some cases where there is more detailed supplementary guidance which is referred to in the text it is cross referenced with internet links. Where credible values cannot be readily calculated but it is clear they relate to a significant issue. They should then be factored in early on in preparation of a proposal, and accounted for during option design, at the longlisting stage during shortlist selection. Further guidance on dealing with unquantified and unmonetisable values is given in Chapters 4, 5 and 6 and Annex A1, and in a range of supplementary guidance referenced on the Green Book web pages for example the Enabling Natural Capital Approach (ENCA) guidance.

Costs and benefits should be calculated over the lifetime of the proposal. Proposals involving infrastructure such as roads, railways and new buildings are appraised over a 60 year period. Refurbishment of existing buildings is considered over 30 years. For proposals involving administrative changes a ten year period is used as a standard measure. For interventions likely to have significant costs or benefits beyond 60 years, such as vaccination programmes, or nuclear waste storage, a suitable appraisal period should be discussed with and formally agreed by the Treasury at the start of work on the proposal. Where a commercial contract is involved, and it covers a short period such as five years for an IT system for example, it is necessary to understand and plan for service delivery over the longer period applicable for the kind of proposal being considered. It is the life of the public service described above that determines the length of the appraisal period. The costs of maintaining the service and of transferring to another system will need to be included and it will need to be planned for. Appraisal of the proposal must include provision of the service when the contract needs to be replaced.

Distributional analysis

Distributional analysis is important where there may be significant redistributive effects between different groups within the UK, resulting from a proposal. The level of detail and complexity devoted to this analysis should be proportionate to the likely impact on those affected. Redistribution may concern any of the groups identified by the Equality Act 2010, and should be considered when applying the Families test introduced in 2014 or where different income groups or types of businesses or geographically defined places in the UK may be affected. See also in Annex 2 and paragraphs 4.15 to 4.19 in Chapter 4. Where a form of distributional appraisal is necessary one of three possible levels of complexity may be regarded as proportionate:

-

Where the level of impact on a defined group or area is very marginal it may be judged that it is sufficient to note the effect and bring it to the attention of the sponsoring Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) and the approving authority to allow judgment on possible action.

-

Where the likely effect is more substantial, then a straight forward and as far as possible, quantified and monetised analysis is required to appraise the effects, and to support judgments by decision makers in considering whether adaptation of the proposal or mitigation of its effects is possible, and to provide relevant options for the decision makers to consider.

-

If there is likely to be a very significant redistribution of income or related social welfare either as an objective or as a collateral consequence of a proposal, then it may be appropriate to employ an equivalised income approach as set out in Annex-3. Where such weighting is employed it must be understood that the results are sensitive to the choice of weights. The reasons for the choices made must be transparently explained. Additional sensitivity tests are required to reveal the difference made by the weighting process and in particular to reveal the impact of varying the weights to reflect the uncertainty they introduce by using the upper and lower limits of the values they can reasonably be expected to take.

Optimism bias, risk and sensitivity analysis

When conducting appraisal consideration should also be given to:

-

optimism bias – this is the proven tendency for appraisers to be optimistically biased about key project parameters, including capital costs and operating costs, project duration, and resulting benefits delivery. Optimistic rather than realistic projections result in undeliverable targets and if permitted across the board create institutional failure as all proposals fall consistently far short of promised results. For this reason, specific optimism bias adjustments must be applied at the start of the process as numbers are initially identified. As proposal specific risks are identified they must be entered into the risk register explained in Chapter 5. As ways of avoiding, sharing or mitigating risks are identified and included in a proposal optimism bias can be proportionately reduced. Initial optimism bias levels recommended by the Green Book must be employed unless the organisation concerned has their own robust alternative estimates based on sufficient reliable data from similar projects. Managing, avoiding, sharing and mitigating risk is the key to successful delivery of well designed proposals, points to note are:

-

risks – that are specifically related to a proposal may arise in the design, creation/building, implementation or operation of a proposal. Risk costs are either the cost of avoiding, sharing or otherwise mitigating risks, or the cost of risk materialising. An estimate of a materialised risk cost should be made using an expected likelihood approach explained in paragraph 5.51 and as set out more generally in Chapter 5 paragraphs 5.47 to 5.52. The objective is to manage risk in a socially cost effective way, not simply to build numbers into a spreadsheet. Risks should be fully understood, and realistic measures built into proposals for their management, this includes low probability but high impact events.

-

fraud risk – there are clear rules and duties of due diligence which must be adhered to when awarding purchasing contracts or other decisions (such as the awarding of grants). This must be considered at an early stage in the process of longlist analysis and the design of the proposal must take into account proportionate counter measures as set out in more detail in Annex 5.

-

sensitivity analysis – is performed to explore the sensitivity of expected outcomes to potential variations in key input variables.

-

switching values can be estimated as part of sensitivity analysis where appropriate. These are the values an input would need to change to in order to make an option no longer viable.

Discounting

All values in the economic dimension are expressed in real prices relating to the first year of the proposal. This means that the average inflation rate is removed. Discounting is based on the concept of time preference, which is that generally people prefer value now rather than later. This has nothing to do with inflation, because it is true even at constant prices. Discounting converts costs and benefits into present values by allowing for society’s preference for now compared with the future. It is used to allow comparison of future values in terms of their value in the present which is always assumed to be the base year of the proposal. For example if Projects A and B have identical costs and benefits but Project B delivers a year earlier, time preference gives Project B, a higher present value because it is discounted by a year less than project A.

In government appraisal costs and benefits are discounted using the social time preference rate as explained in Chapter 5 and paragraphs 5.32 to 5.39 as well as Annex 5. The reason for social discounting is to allow proposals of different lengths and with different profiles of net costs and benefits over time to be compared on a common basis. For reasons explained in Chapter 5 it does not need to be concerned with the cost of capital which is dealt with elsewhere by other means.

Selecting the preferred option and public value for money

The primary reason for implementing all proposals is not a Benefit to Cost Ratio (BCR), but it is to meet the “business need” identified early in developing the rationale for the proposal, this takes place at the start of developing the strategic dimension of the business case. All shortlisted options must be viable and meet the requirement of delivering the SMART objectives. They will differ in timing, risk, cost and benefit delivery at or above the “Do Minimum” option.

Comparison of each shortlist option with Business As Usual, reveals the quantified differences of alternative options. The value of all benefits, less all costs, in each year when discounted can be added together because they are in present value (discounted) terms, and then represent net cost benefit (benefits minus costs). This sum is the Net Present Social/Public Value (NPSV) of a proposal. The NPSV and Benefit Cost Ratio (NPSV divided by relevant public sector implementation costs) produces an initial ranking of options.

Where there is a significant feature the benefits of which are not readily or credibly monetisable, then value for money can be revealed by preparing two alternative versions of the preferred option. One without the unmonetisable benefit and another including it and its additional costs. A comparison of each of the options with BAU enables decision makers to see the additional cost of the unmonetisable benefit and to consider if it is an acceptable price worth paying.

Significant unquantifiable risk and uncertainties are also to be considered at this stage. The choice of the preferred option on grounds of public or social value for money is wider than just the initial BCR.[footnote 4] Optimum value for money is a considered choice starting from the initial option ranking, that also considers important unquantifiable benefits and significant unquantifiable uncertainties and known risks.

Projects do not determine the need for a programme of which they are a part, nor do programmes do so for strategy, or strategic portfolios for policy. The justification of enabling proposals is the wider policy or programme or portfolio of which they are a part. Where social costs and benefits are not sensibly calculable or where they are clearly the same for all options it is sensible to optimise on a cost efficiency basis. For example, a signalling system for railway, must deliver according to a specification provided by the overall programme of which it is a part. There is no need to imagine the signals alone have some social value in isolation from the programme that justifies their existence. Nor is it credible or useful to apportion the overall programme benefits to the signalling component.

2.5 Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring is the collection of data, both during and after implementation. This data can be fed back during implementation as part of managing, and it can be used during operation of a service in the same way, as well as for informing evaluation. It is important to understand and quantify Business As Usual (BAU) so that the setting of SMART objectives is realistic, proposals are founded on sufficient understanding, and performance can be monitored and evaluated.

Evaluation is the systematic assessment of an intervention’s design, implementation and outcomes. It tests:

-

if or how far an intervention is working or has worked as expected

-

if the costs and benefits were as anticipated

-

whether there were significant unexpected consequences

-

how it was implemented and if changes were made why

All proposals must as part of the proposal contain proportionate budgetary, and management provisions for their own monitoring and evaluation. This applies to monitoring and evaluation both during and after implementation. Monitoring and evaluation are an important way of identifying lessons that can be learnt to improve both the design and delivery of future interventions.

3. The Overarching Policy Framework

This chapter provides an overview of how appraisal fits within government decision making processes including the Policy Cycle, the Five Case Model and Impact Assessments.

3.1 Policy and Strategic Planning an Overview

It is vital to understand both the context within which policy objectives are being delivered and the process of change that will result from the proposed intervention and cause the desired policy objectives. This process of causation is referred to in the Green Book as the logical process of change or simply process of change. The supplementary guidance on Business Cases covers in more detail the steps needed to develop, understand and explain, the objective basis of this expectation and provide reasonable evidence. It is the foundation of the rationale for intervention in the way that is proposed.

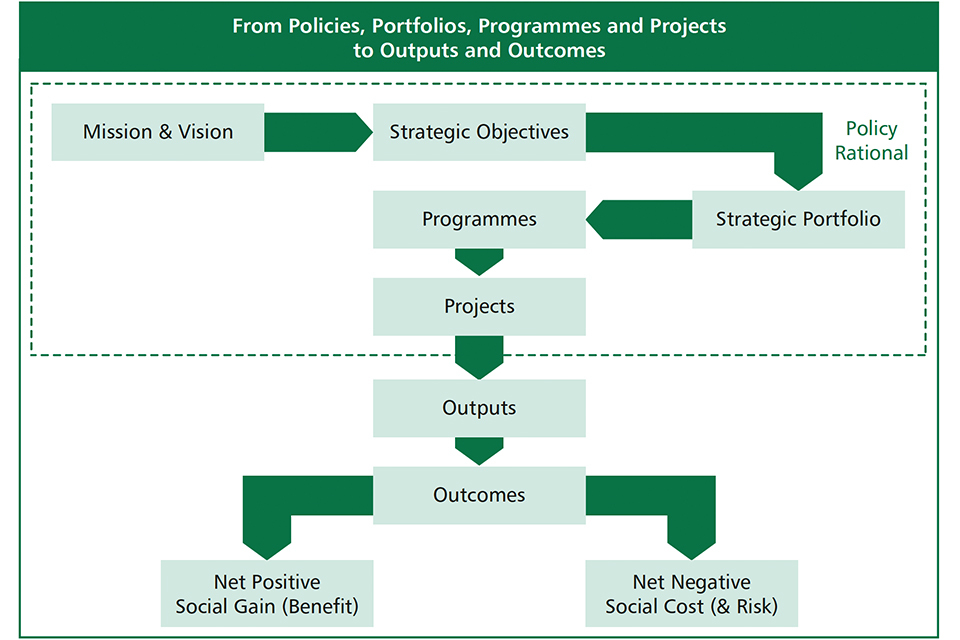

Key issues that influence the wider debate which gives rise to policy development have been summarised in the mnemonic known as PESTLE which stands for Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental and Legal issues. The translation of these issues through policy into outcomes is represented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Policy and the wider context Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, Legal (PESTLE)

Figure 2. Policy and the wider context Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, Legal

Policy development must start with development of the rationale and be based on a sound understanding of the current position. This needs to be understood in objectively quantifiable terms so that the scope and key features of the issues are understood appropriately. Parts of government may from time to time adopt policy priorities and develop policy tests for use in support of these very specific objectives. Where they exist they need to be taken into account when considering policy formation. Such tests are considered at the preliminary research stage and as part of policy design, when considering objectives, and at the longlist stage discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

As indicated in Chapter 2, the development of policy into implementable solutions to deliver objectives, necessarily involves decisions at a number of levels of scale and delegation. Typically, progressing from high level statements of “mission” or purpose through more specific high level strategic policy objectives. Programmes are created to deliver these objectives, these Programmes contain Projects and related activities, that, taken together, are necessary to bring about the changes required to deliver the objectives. These programmes are best developed and managed through strategic portfolios which involve a common policy theme as illustrated in Figure 3. More detailed guidance on developing strategic portfolios, programmes and projects is available on the main Green Book webpage.

Figure 3. From Policy to Outcomes

Figure 3. From Policy to Outcomes

At each of the policy development levels indicted above, the context in terms of objectives is provided by the preceding higher level. The nature of the issues being considered also changes dependent on this context and the scale of the proposal. Thus, programmes are concerned with identifying and managing projects and keeping track of the programme critical path and expected spending envelope. On the other hand, projects are concerned with delivery of specific changes in business outputs. Projects provide the detailed design of output changes and make requests for specific spending.

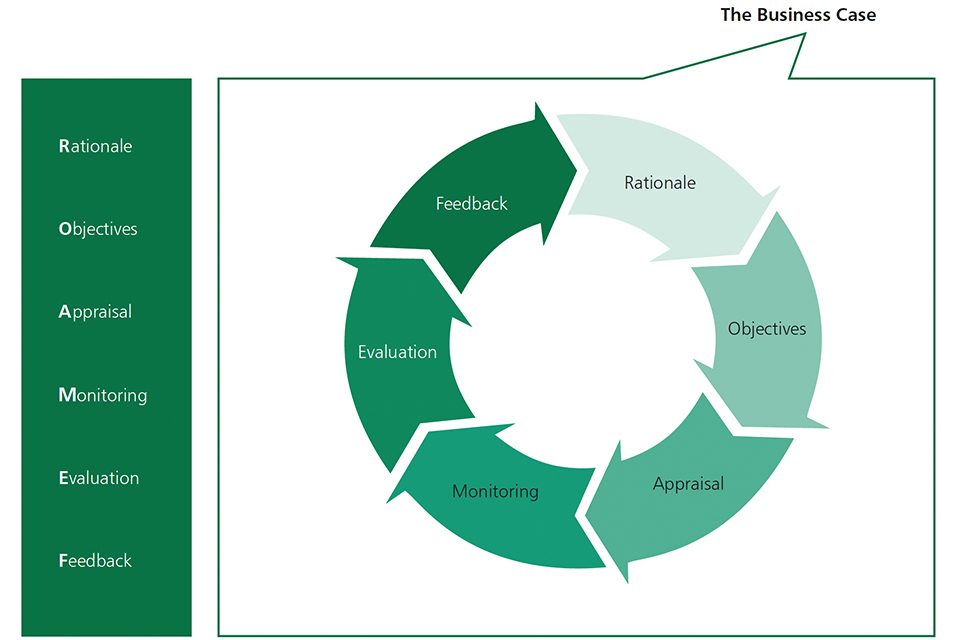

At each level the thinking and development process follows the same high level policy development and review pattern known as the ROAMEF cycle as shown in Figure 4. The process proceeds from developing a rationale for the proposal, through identification of objectives, to options appraisal, monitoring and evaluation. More detailed supplementary guidance supporting the processes outlined above is provided by the family of business case guidance documents available from the Green Book web page.

Figure 4. The ROAMEF Policy development cycle

Figure 4. The ROAMEF Policy development cycle

Monitoring and evaluation play an important role before, during and after implementation. The aim is to improve the design of policies, identify strategic objectives, to understand the mechanism of change and to support the management of implementation.

Strategic portfolios identify, scope, plan, prioritise and manage the constituent programmes needed to deliver the objectives of the portfolio. Each strategic portfolio deals with a different aspect of policy delivery known as a theme and consists of related programmes. A generic example is provided at Figure 5 below and a hypothetical case study example at Figure 6 in Chapter 4. The Green Book supplementary guidance on business cases provides more detailed information.

Figure 5. A generic example of the relationship between Strategy, Programmes and Projects

| Stage | Organisational Strategy | Programme | Project |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose and focus | To deliver the vision, mission and long-term objectives of the organisation, typically involving transformational service change. Organisational Strategy for Transforming a Public Service | To deliver medium term objectives for change, typically involving improved quality and efficiency of service. Programme A: Service Improvement | To deliver short-term objectives, typically involving improved economy of service and enabling infrastructure. Project A: Re-procurement of ICT |

| Scope and content | Strategic portfolio comprising the required programmes on the critical path for delivery of required benefits. Programme A: Service Improvement Programme B: Human Resources Programme C: Estates Management | Programme portfolio comprising the required projects and activities on the critical path for delivery of anticipated outcomes. Project A1: Re-procurement of ICT Project A2: Business Process Re-engineering Project A3: Quality Management | Project comprising the inputs and activities required for delivery of the agreed output. Work streams: Replacement ICT Upgrading ICT Staff training ICT |

| Product | Organisational Strategy and business plans | Programme Business Case (PBC) | SOC, OBC and FBC for large projects BJCs for smaller schemes |

| Monitoring, evaluation and feedback | 5-year strategy. Monitor during implementation. Review at least annually and update as required. | 3-year programme. Monitor during implementation. Evaluate on completion of each tranche and feedback into strategy development. | 1-year project. Monitor during implementation. Evaluate on completion of project and feedback to programme. |

Programmes initiate, align and monitor the constituent projects and related activities needed to deliver outputs that will produce the anticipated outcomes of the programme. These outputs may consist of new products, new or improved services, or changes to business operations. It is not until the projects deliver and implement the required output changes that the outcomes that cause the benefits of the programme can be realised.

Programmes require a continuing process of review and alignment with policy objectives, to ensure that a programme and its projects remain linked to strategic objectives. This is because while they are implementing changes and improvements to business operations, they may need to respond to changes in external factors or to accommodate changes in policy objectives or strategies. The relationship between strategic portfolios, programmes and projects is illustrated by the generic Figure 5 above and the hypothetical practical example in Figure 6 in Chapter 4.

The process of policy development should be based on objective evidence. Where assumptions are needed, they should be reasonable and justified by transparent reference to the research information they are based on. Information may come from a range of possible sources including, evaluation of previous interventions and what works, background academic research, specially commissioned research or surveys, and international comparisons. Research and due diligence activity should take place early on, before the process of more detailed policy development or business case development and appraisal begins.

Box 4. Guidance and definitions and for managing successful Programmes and Projects

A Programme is an interrelated series of Sub-Programmes, Projects and related events and activities in pursuit of an organisation’s long-term goals/objectives.

-

Managing Successful Programmes (MSP), is an international standard originated by the UK government for programme management, it defines a programme as ‘a temporary, flexible organisation created to co-ordinate, direct and oversee the implementation of a set of related projects and activities in order to deliver outcomes and benefits related to the organisation’s strategic objectives’.

-

Large projects are often referred to as programmes. In practice, the key differences between programmes and projects are:

-

Programmes focus on the delivery of outcomes and projects on the delivery of outputs

-

Programmes are comprised of enabling projects and activities

-

Programmes usually have a longer lifespan than projects and usually consist of a number of tranches that take several years to deliver, and

-

Programmes are usually more complex and provide an umbrella under which their enabling projects can be coordinated and delivered.

-

There are different types of programmes, and the content of the supporting business case will be influenced by the nature of the change being delivered and the degree of analysis required.

A Project is a temporary organisation that is needed to produce a specific predefined output or result at a pre-specified time using predetermined resources. Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2 guidance defines a project as ‘a management environment that is created for the purpose of delivering one or more business products according to a specified business case’.

Most projects have the following characteristics:

-

a defined and finite life cycle

-

clear and measurable inputs and outputs

-

a corresponding set of activities and plans

-

a defined amount of resource, and

-

an organizational structure for governance and delivery.

The potential for the proposal to have wider systemic effects across society, the economy and the environment should be considered whether or not they are intentional. Such collateral effects if significant must be taken into account at the longlist stage of the appraisal process, as explained in Chapter 4.

Proposals with long term costs and benefits must consider whether longer term structural changes may occur in the economy or society. Such external structural shifts may arise from demographic, technological, environmental, cultural, or other similar external changes. These potential effects need to be considered and taken into account at the longlisting stage of proposals.

At every level of the decision-making process, whether it concerns strategic portfolios of programmes, a programme, or a project, there is a need to set out the logical chain of cause and effect by which the SMART objectives will be produced. The need for this is widely recognised and, in some places, which lack the five-case model, and its strategic dimension, it has been catered for by approaches labelled as logic models or the theory of change.

In the five-case model, this logical model of cause and effect is necessarily different at each level of the decision-making process. Strategic portfolios are concerned with significant strategic policy objectives, and managing the programmes that will deliver the outcomes required by the policy. Whereas programmes are concerned with organising their constituent projects and related activities. Projects will be concerned with the delivery of specific outputs that enable the programme of which they are a part to change outcomes in society and the economy.

SMART objectives should as far as possible be expressed in terms of outcomes not service outputs. Projects should reflect the programme of which they are a part and they must deliver the outputs that the programme requires. A few projects may be stand alone and some projects within programmes may occasionally need to express some objectives as outcomes. Even where a proposal concerns creating or acquiring an asset, it should be appraised from the perspective of its capacity to deliver the required service levels. This helps to avoid biasing proposals towards initial solutions that may not have been sufficiently thought through.

Transformation in Green Book terms refers to a fundamental change in the structure and operation of the subject that is to be transformed. This differs from a simple change in quantity. It refers to a radical qualitative change in state, so that the subject operates in a very different way or has different properties. An analogy is the change from cold water into ice which is fundamentally different from cold water in both its structure and mechanical properties. For example, internet shopping is transforming retail shopping and consequentially the nature of many high streets.

Where proposals claim to be aiming for “transformational change” the nature of the change needs to be transparently explained. A credible explanation of the change process is required with the objective evidence on which it is based and objective support for assumptions made. Where the effects may be in practical terms irreversible, and intergenerational wealth transfers are involved, it is particularly important to take account of long-term structural changes and systemic impacts. In such cases sensitivity analysis and in many cases scenario analysis is important as explained in Chapters 4, 5 and 6.

The purpose of longlist appraisal is to narrow down possible options to identify an optimum shortlist of viable options for detailed appraisal. Shortlist appraisal can only support choice between the options offered to it. The selection of a credible and viable list of the best options for detailed appraisal is therefore vital to avoid pointless analytical work to support a choice between suboptimal options at the shortlist stage.

The primary focus of the business case process and appraisal is to identify and define the options and to support advice on prioritisation and choice. The objectives of a project are derived from the programme of which it is a part. The objectives of the programme reflect policy and are shaped by the strategic portfolio of which it is a part and the overall policy objectives determined by government. The focus is therefore on identifying the best possible options and choosing between them by identifying the optimum. Strategic policy justification is part of the high-level strategic analysis that takes place when overarching policy is being researched and options for policy at a high level are being explored. A hypothetical example showing the relationship between strategy programmes and policies is given in Figure 5 above, it is quoted from the programme business case guidance on the Green Book web page which is accessible at this link.

3.2 The Five Case Model

The Five Case Model is the required framework for considering the use of public resources to be used proportionately to the costs and risks involved, and taking account of the context in which a decision is to be taken. The five “cases” or dimensions are different ways of viewing the same proposal, outlined in Box 5 below. The policy, analytical, commercial, financial, and delivery professions within the public service must avoid working in silos and work together on proposals from the outset. The five dimensions cannot be developed or viewed in isolation, they must be developed together in an iterative process because they are intimately interconnected.

The five case model provides a universal thinking framework that if understood and applied correctly accommodates the widely varied features of any investment or spending proposal. There is no need to invent an additional case to accommodate a special feature of a proposal, the model takes account of such features which are expressed as either objectives to be achieved or as constraints that a proposal has to work within such as a legal, regulatory, or ethical consideration.

Box 5. The Five Case Model

Strategic dimension

What is the case for change, including the rationale for intervention? What is the current situation? What is to be done? What outcomes are expected? How do these fit with wider government policies and objectives?

Economic dimension

What is the net value to society (the social value) of the intervention compared to continuing with Business As Usual? What are the risks and their costs, and how are they best managed? Which option reflects the optimal net value to society?

Commercial dimension

Can a realistic and credible commercial deal be struck? Who will manage which risks?

Financial dimension

What is the impact of the proposal on the public sector budget in terms of the total cost of both capital and revenue?

Management dimension

Are there realistic and robust delivery plans? How can the proposal be delivered?

Strategic dimension

The strategic dimension of the Five Case Model must identify “Business as Usual” (BAU) – that is the result of continuing without implementing the proposal under consideration. This must be a quantified understanding to provide a well understood benchmark, against which proposals for change can be compared. This is true even when to continue with BAU would be unthinkable.

The strategic dimension is where external constraints that a proposal must work within are considered, for example, legal, ethical, political, or technological factors. External dependencies must also be identified, such as necessary infrastructure over which the proposal has no control.

The outcome that the proposal is expected to produce is defined by a small number (up to 5 or at most 6) of SMART objectives that must be Specific Measurable Achievable Realistic and Time-limited. The SMART objectives selected in the strategic dimension must directly drive the rest of the process throughout the model. Crucially they provide the basis of option creation and the appraisal process in the economic dimension.

Programme objectives should be expressed in terms of outcomes that the expected change in service provision is expected to produce. This is a key element in understanding and refining the objective which should be expressed numerically. The objectives must directly reflect the rationale for the proposal and be able to be monitored and evaluated.

Box 6. Logical Change Process

The Strategic dimension of the Business Case requires a Strategic Assessment key steps in which are:

-

A quantitative understanding of the current situation known as Business As Usual (BAU)

-

Identification of SMART objectives that embody the objective of the proposal

-

Identification of the changes that need to be made to the organisation’s business to bridge the gap from BAU to attainment of the SMART objectives. These are known as the business needs.

-

An explanation of the logical change process i.e. the chain of cause and effect whereby meeting the business needs will bring about the SMART objectives.

This all needs to be supported by reference to appropriate objective evidence in support of the data and assumptions used including the change mechanisms involved. It should include:

-

the source of the evidence;

-

explanation of the robustness of the evidence; and

-

of the relevance of the evidence to the context in which it is being used.

-

This provides a clear testable proposal that can be the subject of constructive challenge and review. Single point estimates at this stage would be misleading and inaccurate and objectively based confidence ranges should be used.

The key part of all proposals, whether strategic portfolio, programme or projects, is the strategic assessment which examines the current position (Business As Usual) and compares it with the desired outcome, as summarised by the SMART objectives. The gap which needs to be bridged between Business As Usual and the attainment of the SMART objectives represents the business needs. An objectively based understanding of how meeting the business needs will result in attainment of the SMART objectives, is a basic requirement – see Box 6 and the Green Book Supplementary Guidance on Business Cases concerning strategic assessment.

From this early stage how a proposal fits with wider public policy and any potential impacts on the operations, responsibilities or budgets of other public bodies must be considered. Consultation and cooperative working between public bodies supports effective and efficient delivery of public services and avoids unnecessary waste and inefficiencies.

Research, consultation and engagement with stakeholders, should be conducted from the earliest stage. This provides greater understanding of the current situation and potential opportunities for improvement including links to relevant policies.

Economic dimension

The economic dimension is the analytical heart of a business case where detailed option development and selection through use of appraisal takes place. The economic dimension of the business case is driven by the SMART objectives and delivery of the business needs that are identified in the strategic case as explained in Chapter 4. It estimates the social value of different options at both the UK level and, where necessary on different parts of the UK or on groups of people within the UK. Where overseas development assistance is concerned the value to the recipient country is relevant. The potential for the proposal to cause significant unintended consequences should also be considered and where they are likely they must be taken into account

Longlist appraisal and selection of the shortlist is a crucial function of the economic dimension explained more fully in Chapter 4, and in the family of Business Case Guidance documents available from the Green Book web pages. The selection of a preferred option from the shortlist requires interaction between the strategic and economic dimension and the commercial, financial and management dimensions of the case. None of these can be considered in isolation, and the supplementary guidance on Business Cases should be followed to ensure that the proposal is developed in an integrated, way bringing together all of the dimensions together with the benefit of key stakeholder input.

The selection of the preferred option from the shortlist uses social cost benefit analysis or where appropriate social cost effectiveness analysis as explained in Chapter 5. The value for money recommendation is based upon a range of factors including the net social value of the option including the costs of risk and residual optimism bias, the net whole life cost of the public resources employed, and the additional costs of including key objectives, the benefits of which are unquantifiable. The overall risk of the option to the public and the public sector is also an important consideration.

Commercial dimension

The commercial dimension concerns the commercial strategy and arrangements relating to services and assets that are required by the proposal and to the design of the procurement tender where one is required. The procurement specification comes from the strategic and economic dimensions. The commercial dimension feeds information on costs, risk management and timing back into the economic and financial dimensions as a procurement process proceeds. This is part of the iterative process of developing a proposal into a mature business case. The Cabinet Office Functional programmes can provide support and advice during appraisal e.g. the Commercial Function can support assessment of procurement decisions.[footnote 5]

Financial dimension

The financial dimension is concerned with the net cost to the public sector of the adoption of a proposal, taking into account all financial costs and benefits that result. It covers affordability, whereas the economic dimension assesses whether the proposal delivers the best social value. The financial dimension is exclusively concerned with the financial impact on the public sector. It is calculated according to National Accounts rules.

Management dimension

The management dimension is concerned with planning the practical arrangements for implementation. It demonstrates that a preferred option can be delivered successfully. It includes the provision and management of the resources required for delivery of the proposal and arrangements for managing budgets. It identifies the organisation responsible for implementation, when agreed milestones will be achieved and when the proposal will be completed.

The management dimension should also include:

-

the risk register and plans for risk management

-

the benefit register

-

the arrangements for monitoring and evaluation during and after implementation and any collection of data prior to implementation, including the provision of resources and who will be responsible

The management dimension is completed more fully during the middle and latter stages of a proposal’s development into a full business case. The implications of the management dimension feed into the appraisal and must be reflected in the full versions of the economic, commercial and financial dimensions.

3.3 Regulatory Impact Assessments

Regulatory Impact Assessments (RIAs) are used to support the appraisal of new primary or secondary legislation, or in some cases the impact of non-legislative policy change. The Green Book should be used for the appraisal required for RIAs, in the same way as for spending proposals. It sets out the methodology for appraisal of social value and distributional effects.

RIAs follow the same logic as spending and resource appraisals and make use of the five case model in their thinking. There needs to be the same rationale with clear policy objectives, and expected process of change and SMART policy objectives. Costs, benefits and risks to the public and those affected as well as to the public sector are relevant and where new policies are concerned, consideration of a range of options. The calculation of costs and benefits, as well as the detailed evidence base which supports RIAs, should be developed in accordance with Green Book methodology. For small regulatory changes standalone RIAs may not be required, though any analysis included to support these changes should be in line with Green Book methodology.

The rules for the scrutiny and clearance processes, in England, for regulations with an impact on business above a certain value and methodology for calculating specific metrics relating to the impact on business, are set out in the Better Regulation guidance. The Better Regulation guidance reflects ministerial decisions on statutory reporting duties and may be periodically updated to reflect policy change.

3.4 Option appraisal in government

The Green Book methodology set out in this guidance should be applied proportionately to support effective decision making across government. Some problems such as emergencies are not covered by the regular approval process. Some questions arise that do not involve the use of significant resources, the answers to which hinge on issues of social value alone. These may use only part of the process covered here, but in most cases key elements of the thinking model apply, and its use supports rapid, effective and efficient decision making, supported by objective advice.

4. Generating Options and Long-list Appraisal

This chapter sets out how to develop a rationale for intervention, generate a longlist of possible options to achieve objectives and filter them down to a shortlist suitable for detailed cost benefit or cost effectiveness analysis. These methods and principles apply when considering all significant proposals, for intervention for example regulatory options or options concerning the use of existing resources as well as new public spending and investment. As a guide to navigation a summary of the Appraisal Framework is shown throughout this guidance, below over the page in Box 7 the rationale stage is highlighted.

4.1 Rationale

In central government the objectives of policy at the highest level are determined by Ministers who are responsible to Parliament. Within the frameworks that are provided by Ministerial decisions and by the law, decision makers in other public bodies also have responsibility for setting policy objectives. The role of public officials and of this guidance is to provide objective unbiased advice to decision makers, to support choice between alternative means of realising the policy objectives that have been set.

Ideally policy objectives should be framed as social outcomes. This longlist stage of the process includes the estimation of indicative social costs and benefits including the cost of risks that result from different options. These indicative values should be expressed as ranges. As the appraisal process progresses and knowledge increases, accuracy will improve resulting in a narrowing of these ranges. While absolute certainty is not a realistic expectation, unbiased estimates within reasonable ranges accompanied by plans to manage uncertainty are a requirement.

A “rationale” explaining the desired change, and crucially the means by which it can be brought about, must be developed as outlined in Chapter 3. The rationale relates to the context of the proposal and its place in the chain of decision making,[footnote 6] the objectives of which run like a thread from Strategy, through programmes and in to projects. The content of the rationale will relate to both the context set both by its place in the chain of decision making and the nature of the proposal concerned. A clear explanation is required of the chain of cause and effect that is expected to support attainment of the objectives. It must also explain how the proposal fits with the objectives of the stages before it in the decision chain.

Different organisations and arms of public service should act in ways that are mutually supportive and cooperative. Therefore, from the start proposals must be designed to ensure they provide a supportive strategic fit with wider public policies as described in Chapter 3. Where proposals are likely to rely on or impinge upon the policies or responsibilities of another public body, there is a duty for public organisations to work together to ensure that a positive result for the public is produced.

Box 7. Navigating the Appraisal Framework: the Rationale

Rationale for intervention

-

conduct the strategic assessment, research and understand the current position – Business As Usual

-

establish rationale for intervention including the Evidence based Logical Change Process

-

determine whether Place Based, Equalities, and/or Distributional Appraisal is required

-

ensure Strategic Fit and identify SMART objectives (outcomes and outputs) for intervention

Longlist appraisal

-

identify Constraints and Dependencies

-

consider Place Based, Equalities, and/or Distributional objectives

-

identify Critical Success Factors (CSFs)

-

consider unquantifiable and unmonetisable factors

-

consider a longlist of option choices with the Options Framework-Filter

-

consider Place Based, Equalities, and Distributional effects

-

using the Options Framework-Filter create a viable shortlist and preferred way forward

Shortlist appraisal

-

select Social Cost Benefit Analysis or Social Cost Effectiveness Analysis

-

identify and value costs and benefits of all shortlisted options

-

estimate the financial cost to the public sector

-

ensure all values in the economic dimension are in real base year prices with inflation removed

-

qualitatively assess non-monetisable costs and benefits

-

apply appropriate Optimism Bias

-

maintain Risk and Benefits Registers

-

assess Avoidable, Transferable and Retained Risk, build in additional Risk Costs and reduce Optimism Bias accordingly

-

sum the values of costs and benefits in each year

-

discount the yearly sums of costs and benefits in each year to produce Net Present Social Values (NPSVs)

-

add the NPSVs over time to produce The Net Present Social Value (NPSV) of each option

-

calculate Benefit Cost Ratios (BCRs) if using CBA or Social Unit Costs if using CEA as appropriate

Identification of the preferred option

-

identify preferred option considering NPSV, BCR, unmonetisable features risks and uncertainties

-

conduct sensitivity analysis and calculate switching values, for each option

Monitoring and evaluation

-

during implementation – inform implementation and operational management

-

in the operational phase – inform both operational management and evaluate the outcome and lessons learned to improve future decisions.

Policies generally consist of programmes to bring about change. Programmes are best organised and managed in strategic portfolios that support particular themes within the overall policy objective, for example see Figure 6 below. Programmes are comprised of projects, which individually deliver changes in service outputs. Together the projects, through the delivery of change in their outputs, support delivery of a change in outcomes which are the objectives of the programme. The family of supplementary guidance on different types of business cases are available at this link and they provide the detailed guidance necessary for use when preparing spending proposals. The models and method are also applicable to other kinds of decisions such as regulatory or asset disposal issues.

Figure 6. A hypothetical applied example the relationships between Strategy, Programmes and Projects

| Organisational Strategy | Programme | Project | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose and focus | To deliver the vision, mission and long-term objectives of the organisation, typically involving transformational service change. National Strategy for Improving Pre-16 year old Educational Attainment | To deliver medium term objectives for change, typically involving improved quality and efficiency of service. Improving School Buildings Programme | To deliver short-term objectives, typically involving improved economy of service and enabling infrastructure. Regional School Improvement Project A |

| Scope and content | Strategic portfolio comprising the required programmes on the critical path for delivery of required benefits. Improving Schools Building Programme Review of Pre-16 Curriculum Programme School Teachers Training Programme | Programme portfolio comprising the required projects and activities on the critical path for delivery of anticipated outcomes. Regional School Improvement Project A Regional School Improvement Project B Regional School Improvement Project C | Project comprising the products and activities required for delivery of the agreed output. Work streams: School building refurbishment New equipment Upgrading & Replacement IT |

| Product | Organisational Strategy and business plans | Programme Business Case (PBC) | SOC, OBC and FBC for large projects BJC for smaller schemes |

| Monitoring, evaluation and feedback | 10 year strategy Review at least annually and update as required. | 7 year programme Monitor and Evaluate during implementation and on completion of each tranche. Annual reviews as a minimum and feedback into strategy development. | 2 year project Monitor and Evaluate during implementation and on completion of project and feedback to programme. |

Proposals for change must start from a thorough objective and quantitative understanding of the current situation, this should be informed by research and consultation with experts and stakeholders. A clear quantitative understanding of “Business As Usual” (BAU) is essential to understanding the current situation, and to identifying and planning the changes that may be required. All those involved in appraisal, and in development of business cases, and in their review and approval must be trained and accredited. Details of the appropriate HM Treasury approved training and accreditation scheme are given at this link.

Business As Usual (BAU) in Green Book terms is defined as the continuation of current arrangements, as if the proposal under consideration were not to be implemented. This is true even if such a course of action is completely unacceptable. The purpose is to provide a quantitative benchmark, as the “counterfactual” against which all proposals for change will be compared. BAU does not mean doing nothing, because continuing with current arrangements will have consequences and require action resulting in costs, in practical terms there is therefore no do-nothing option.

4.2 SMART objectives

-

Clear objectives are vital for success. Identifying objectives begins at the outset or when making the case for change (part of the strategic dimension explained in more detail in Chapters 3 and 4 and in the Business Case Guidance. A lack of clear objectives negates effective appraisal, planning, monitoring and evaluation. Objectives must be SMART that is:

-

Specific

-

Measurable

-

Achievable

-

Realistic

-

Time-limited

SMART objectives must be objectively observable and measurable, so that they are suitable for monitoring and evaluation (see Chapter 8).

The identification of “SMART” objectives is a crucial part of the rationale, whether they are for a strategic portfolio, or programme, or project. They summarise quantitively the desired outcomes of the proposal. Taken together with the quantified BAU, the SMART objectives support a “GAP” analysis. This is used to identify the internal business changes that need to be made to move from the current BAU position to the desired outcome. The business changes required which this GAP analysis identifies are known as the core “Business Needs,” these needs must be met to achieve the core requirements of meeting the SMART objectives. At this early stage in appraisal it is expected that only indicative estimates of principal costs and benefits are available. As proposals are developed it is likely to be necessary to revise or refine early quantitative estimates and on occasion this may require resetting of quantitative objectives.

Up to 5 or 6 SMART objectives should be established. More than this and a proposed scheme is likely to lack focus and is more likely to fail or significantly exceed costs and under-deliver. The SMART objectives of portfolios and programmes are expressed as outcomes. Outcomes are the external consequences of changes in service outputs. Where projects are part of a programme, the project objectives are outputs required to enable delivery of the programme.

4.3 Important factors when considering the longlist

Constraints

Constraints are external considerations that set limits, within which a proposal must work, for example the law, ethics, social acceptability, timing, practicality and strategic fit with wider public policies and strategy. Constraints must be identified and understood at the earliest possible stage, and taken into account when considering the longlist.

Dependencies

Dependencies are external factors such as infrastructure that an option is reliant upon to be successful, but which are beyond its direct control. The successful delivery of the proposal’s objectives depends on them being present and functioning, for example a digital development proposal would be dependent on users having access to adequate internet connectivity and capacity.

Unmonetizable and Unquantifiable benefits

Where it is thought that there is a benefit to society in implementing a proposal including a feature, the benefit of which is not readily or credibly quantifiable or monetisable, it should be considered as follows: At the longlist stage when creating a shortlist, a version of the preferred way forward[footnote 7] that includes provision of the feature with unmonetised benefits and an otherwise identical option without this provision should be produced. The costs and risks of each of these two options will naturally vary. Both should be taken forward to the shortlist stage so that in the final selection process the price of inclusion of the additional provision is revealed by comparison. The decision maker can then judge whether that additional cost is a price worth paying.

Collateral effects and unintended consequences

Collateral effects both positive and negative may result from an intervention and unintended consequences may occur as a result. These may affect particular groups in society or parts of the country. It is important to think about this when developing and appraising the longlist of options. This is especially true where proposed changes may create new opportunities, obligations or incentives. It is necessary to consider possible beneficial and adverse effects of changes in behaviour that may result from the intervention. The following paragraphs 4.15 to 4.18 are directly relevant to this consideration.

Appraising Targeted Place Based effects

Where objectives are targeted at geographically defined parts of UK, appraisal concerns the local effects produced by a flow of new and existing resources into the target areas. It is also concerned with the consequential effects on similar areas that may be adversely or favourably affected. This is, in contrast to UK policies where the effects on the UK as a whole are the subject of advice on alternative options. UK effects remain of relevance to place based policies, as a check against serious negative consequences at a UK level. It is however, the effects on the target areas and the consequential effects on related places that may be affected, such as travel to work areas that are the main focus of advice. The point of this advice to is support the choice between the alternative options for delivering the place based policy objectives.

Appraising Collateral effects on Places and Groups within the UK

National policy objectives that may have significant favourable or adverse effects on parts of the UK, should also be appraised from the relevant place based perspective, as well as from that of the UK as a whole. Where either UK or place based policies are likely to have significant effects on groups in UK society that are specified by the Equality Act 2010, or on families under provisions of the Family test 2014, these also need to be appraised. This consideration supports advice to decision makers based on a wider view of the effects of alternative options than just reporting on a nationwide bottom line. The results of this appraisal must be made visible to decision makers – see Chapter 7.

Equality and Family Effects

Equalities effects must be considered at the longlist stage and taken into account and where quantified also at the shortlist stage, as required by the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED). This obligation was created under the Equality Act 2010, it requires public sector bodies to “have due regard to advancing equality.” Consideration of equality issues must influence the decisions reached by public bodies. Decision makers should therefore be informed of the potential effects of intervention on groups or individuals with characteristics identified by the Act. The “Family test” introduced in October 2014 should also be considered where there may be significant effects on families and children. See Annex A.1 for more detailed information. This requirement for consideration also extends to long-list stage and throughout the appraisal process.

The Public Sector Equality Duty covers 9 protected characteristics as follows:

-

age,

-

disability,

-

gender reassignment,

-

pregnancy and maternity,

-

race,

-

religion or belief,

-

sex and sexual orientation.

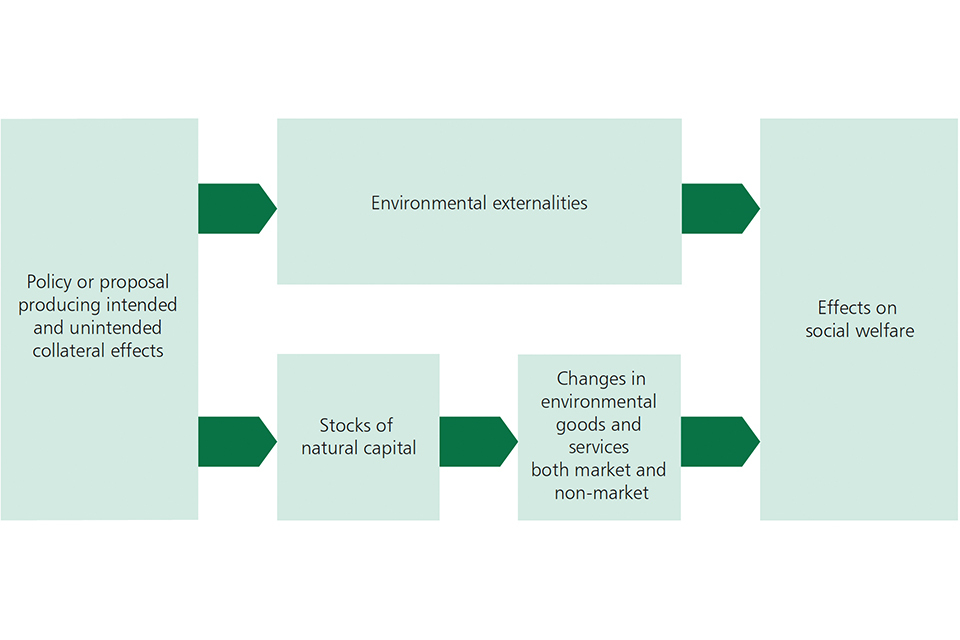

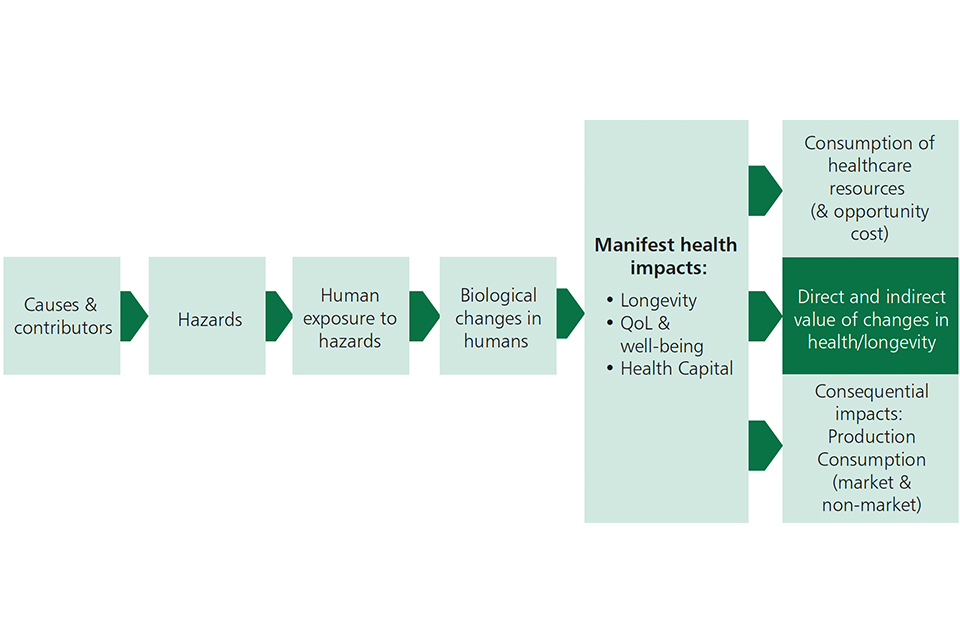

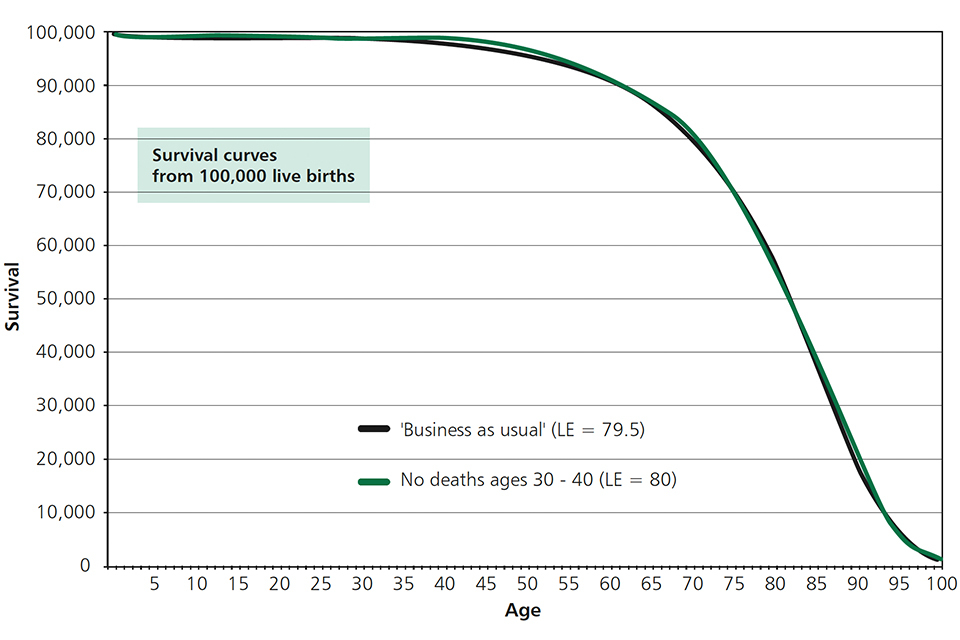

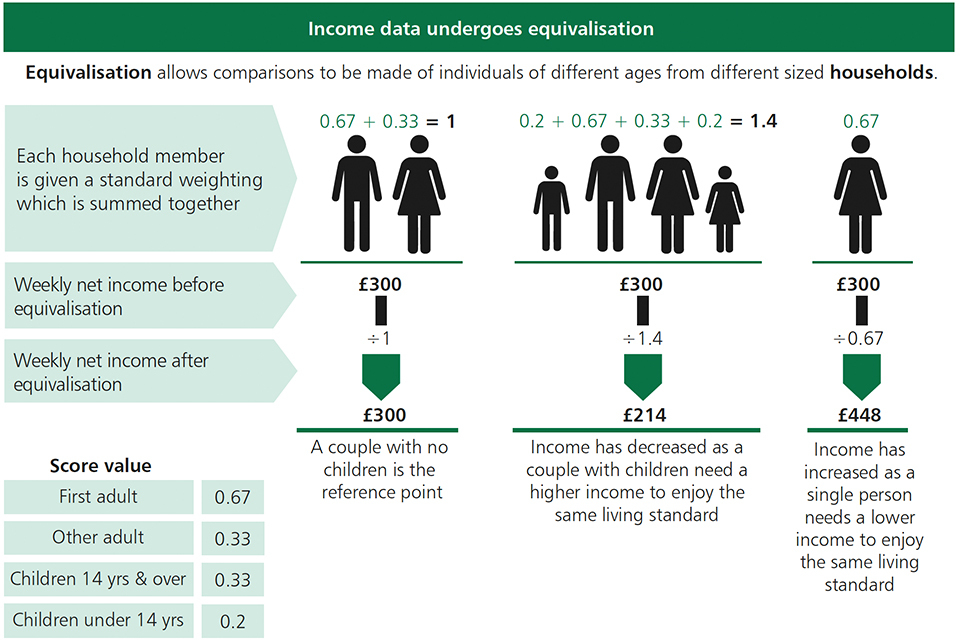

Income Distribution at the longlist stage