National Reference Test Results Digest 2021

Published 9 December 2021

Applies to England

1. Introduction

Ofqual has contracted the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) to develop, administer and analyse the National Reference Test (NRT) in English and maths. The first NRT took place in 2017 and established a baseline from which any future changes in standards can be detected. This report represents an overview of the findings of the 2021 testing process.

The NRT, which consists of a series of test booklets, provides evidence on changes in the performance standards in GCSE English language and maths in England at the end of key stage 4. It does this by testing content taken from the revised GCSE English and maths curricula. It has been designed to provide additional information to support the awarding of GCSEs in English language and maths and is based on a robust and representative sample of Year 11 students who will, in the relevant year, take their GCSEs. In 2021, the Year 11 cohort did not take their GCSE examinations due to the pandemic. Instead, GCSE grades were awarded based on a model of teacher-assessment and therefore the NRT was not used as a source of evidence when setting grade boundaries (Guidance on awarding qualifications in summer 2021 and Information for the submission of teacher assessed grades in summer 2021).

More information about the NRT can be found in the [NRT document collection].(https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/national-reference-test-information)

The first live NRT took place in 2017. The outcomes of the 2017 GCSE examinations in English language and maths provided the baseline percentages of students at three grade boundaries and these were mapped to the NRT for 2017 to establish the corresponding proficiency level. The percentages of students achieving those proficiency levels in each subsequent year are calculated and compared.

The NRT structure is intended to remain the same each year. For each of English and maths, there are eight test booklets in use. Each question is used in two booklets, so that effectively all the tests can be analysed together to give a single measure of subject performance. This is similar to other studies that analyse trends in performance over time, for example, international surveys such as PISA and TIMSS.

This report provides summarised information of the key performance outcomes for English and maths in 2021 and provides information on the changes from the baseline standards established in 2017. It also includes data on the achievement of the samples, their representativeness and the performance of the students on the tests. Further information on the nature of the tests, the development process, the survey design and its conduct, and the analysis methods used is provided in the accompanying document: Background Report: National Reference Test.

2. The sample

The main impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the delivery of the 2021 NRT was the postponement of the testing window. In a normal year, the NRT would be administered over a 10-day period in late February or early March. The 2021 NRT took place later, over 24 days between 19 April and 21 May 2021. The numbers of participating schools and students are shown in Table 2.1. This was a much smaller sample than in previous years. It should be noted that a higher number of schools were drawn in 2021 (n=360) compared to 2020 (n=348) to account for the possibility that fewer schools would be able to participate due to the impact of the pandemic. Initially, 348 schools were recruited to take part in the 2021 NRT, which exceeded the usual target of 330 schools. However, the postponement of the test until the summer term resulted in many schools requesting to withdraw from the NRT. In total, more than a third of the originally recruited sample withdrew between the communication of the new testing dates and the end of the testing period.

Table 2.1. Target sample sizes and achieved samples in current and previous years

| NRT Target Sample | Achieved sample 2021 | Achieved sample 2020 | Achieved sample 2019 | Achieved sample 2018 | Achieved sample 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English: Number of Schools | 330 | 214 | 332 | 332 | 312 | 339 |

| English: Number of Students | 6,732* | 4,030 | 6,639 | 6,739 | 6,193 | 7,082 |

| Maths: Number of Schools | 330 | 216 | 333 | 331 | 307 | 340 |

| Maths: Number of Students | 6,732* | 4,143 | 6,756 | 6,825 | 6,169 | 7,144 |

*The target number of students is based on an attendance rate of 85% of the total number of students if the maximum number of schools are recruited.

The sample was stratified by the historical attainment of schools in GCSE English language and maths and also by school size. In addition, the types of schools were monitored. Checks were made on all three of these variables to ensure that the achieved sample was close to that drawn in the sampling frame; this was generally the case but not entirely.

The number of independent schools participating in the NRT has varied across the years although they have been under-represented in all years of the NRT and no independent schools took part in 2021[footnote 1]. As a result of this, other school types are slightly over-represented in the sample, aside from academy converters which are slightly under-represented. The lack of independent schools may have resulted in the final sample being slightly lower attaining than the national population. When broken down into the five groups (strata) used for the purpose of sampling, schools with lower historical GCSE attainment are slightly over-represented in the achieved sample for 2021, while schools with middling historical GCSE attainment are under-represented. Schools with higher historical attainment are well represented despite no independent schools taking part. Overall, the distribution of historical GCSE attainment at school level was very similar, despite the reduced sample size and lack of independent schools.

2.1 Sample representation

Given the much lower participation rate for the NRT in 2021, there was more potential for bias in the sample to have an impact on the validity of the outcomes, and additional checks were made on the representation of the sample this year for this reason. The first checks made focused on differences in the historical GCSE performance of schools in the sample. Historical GCSE performance was used because it is the stratification variable used in sample selection, being the closest proxy we have to the NRT outcome variables. Overall, this analysis is reassuring in demonstrating that, although the 2021 achieved sample is smaller than in previous years, there is no evidence of change of bias in terms of the stratifying variable.

In addition to historical GCSE performance, a number of other school factors which could have affected performance more than usual this year due to the impact of Covid-19 were also investigated. The sample has therefore been broken down additionally by the proportion of students eligible for free school meals (FSM), geographical region and absence rates during the autumn term in 2020. Within the sample of schools that participated in NRT 2021, schools with the lowest levels of FSM are under-represented. As was the case in 2020 this under-representation is likely to be due to independent schools’ low or non-participation. The highest two bands of FSM eligibility are over-represented in 2021 compared with 2020, leading to a general shift to participating schools in 2021 having higher levels of FSM eligibility. When looking at regional representation in 2021, the Yorkshire and the Humber region was over-represented and the South East was under-represented. In 2020, the East Midlands and North West were over-represented while London and the South East were slightly under-represented. While the data here shows that the NRT samples do not perfectly represent schools in terms of characteristics such as proportion of students with FSM and geographical region, they do indicate that there has not been a major change compared with 2020. Analysis of the absence rates during the autumn term 2020 found that there were no significant differences in the absence rates during this term between those schools that participated in NRT 2021 and those schools which refused to participate or withdrew when the testing window changed.

The evidence suggests that although the precision of the outcomes may be reduced by the smaller sample size, the outcomes can still be considered valid. The caveat should be borne in mind, however, that there is no direct measure available of how individual schools coped with the impact of the pandemic, and we cannot rule out the possibility that the schools that struggled more with the impact may have been more likely to withdraw from the NRT.

2.2 Student participation

Table 2.2 shows the number of students in the final sample for whom booklets were dispatched and the number completing the tests for both English and maths. As this shows, around 80% of students who were selected took part in the tests. Although this is a relatively high participation rate it is below the rate achieved in previous years.

Table 2.2. Completed student test returns for English and maths 2021

| Test type | No. of students: dispatched tests* | No. of students: completed tests | % of students: completed tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | 5124 | 4030 | 79 |

| Maths | 5152 | 4143 | 80 |

*This is lower than the number of students sampled as a large proportion of schools withdrew from testing following the postponement of the testing window.

In total, 1,094 students from 214 schools were recorded as non-attendees during the English NRT, which is 21% of the total number of 5,124 sampled students spread across the schools participating in the assessment. A total of 1,009 students from 216 schools were recorded as non-attendees during the maths NRT, which is 20% of the total number of 5,152 sampled students spread across the schools participating in the test.

The pattern of non-attendance is similar in maths to English. The principal reason given for non-attendance was absence due to illness or other authorised reason, which accounted for 54% of non-attendance for English and 55% of non-attendance for maths. Students being absent from the testing session but present in school remains the second most frequently recorded reason, accounting for 15% for English and 16% for maths. Of the remaining reasons for non-attendance, around 5% of students were withdrawn by the headteacher (6% for English and 4% for maths) and another 6% of students had left the school.

The percentage of non-attendance in 2021 was higher than that seen in previous cycles of NRT. Student participation rates in 2021 were 79% for English and 80% for maths. This is lower than the student participation rates achieved in earlier years of NRT (between 84% and 86%) but comparable with the response rate required in large scale international studies. In addition, there was no evidence that the pattern of student attendance has changed relative to previous years.

2.3 Access arrangements

The NRT offers access arrangements consistent with JCQ requirements (for GCSE examinations) in order to make the test accessible to as many sampled students as possible. Schools were asked to contact NFER in advance of the NRT to indicate whether any of their students required modified test materials or if students’ normal working practice was to use a word processor or laptop during examinations. In cases where additional time would be needed for particular students, schools were asked to discuss this need with the NFER test administrator and ensure that the extra time for the testing session could be accommodated. All requests from schools for access arrangements and the type of arrangement required were recorded. Table 2.3 shows the different types of access arrangements that were provided to students for the 2021 NRT, organised by NFER. This table includes instances where students required more than one access arrangement. These are the access arrangements facilitated by NFER for the NRT in 2021; we do not collect complete data on the permitted arrangements that are made by schools. Overall, the percentage of sampled students receiving access arrangements was similar to 2020.

Table 2.3. Number of access arrangements facilitated by NFER in 2021

| Arrangement provided | No. of students English | No. of students maths | Total number of students | % of sampled students |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online test | 154 | 85 | 239 | 2.3 |

| NFER laptop | 7 | 3 | 10 | 0.1 |

| Different colour test paper | 75 | 57 | 132 | 1.3 |

| Modified enlarged print | 13 | 8 | 21 | 0.2 |

| Enlarged copies | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.02 |

| Braille | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Total | 249 | 156 | 405 | 3.9% |

Due to some students having multiple access arrangements, they will be featured twice in the table

Other access arrangements such as readers, scribes, extra time and examination pens were organised by the school and are therefore not included in the table above.

3. Results for the test booklets in 2021

Details of the analysis procedures are given in the accompanying document: Background Report: National Reference Test Information. The analysis process followed a sequence of steps. Initially, the tests were analysed using Classical Test Theory to establish that they had performed well, with appropriate difficulty and good levels of reliability. The subsequent analyses used Item Response Theory (IRT) techniques to link all the tests together and estimate the ability of all the students on a common scale for each subject, independent of the test or items they had taken. These ability estimates were then used for calculating the ability level at the percentiles associated with the GCSE grade boundaries in 2017. From 2018 onwards, the percentages of students achieving above these baseline ability levels are established from the NRT.

English

The results of the Classical Test Theory analyses are summarised in Table 3.1. This shows the range of the main test performance statistics for the eight English test booklets used.

Table 3.1. Range of Classical Test Theory statistics for the English tests in 2021

| Classical Test Theory statistic | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Students Taking Each Test Booklet | 492 | 518 |

| Maximum Score Attained (out of 50) | 41 | 43 |

| Average Score Attained | 18.7 | 20.3 |

| Standard Deviation of the Test Booklets | 8.1 | 10.0 |

| Reliability of the Tests (Coefficient Alpha) | 0.74 | 0.80 |

| Average Percentage of Students Attempting Each Item (%) | 91 | 93 |

These results show that the English test booklets functioned well, and similarly to previous years. The booklets were challenging, with few students attaining over 40 marks and average scores somewhat less than half of the available marks. The standard deviation shows that the scores were well spread out, allowing discrimination between the students. This is confirmed by the reliability coefficients which are at a good level for an English test of this length. Finally, the average percentage of students attempting each item was over 90% for all booklets, this indicates that the students were engaging with the test and attempting to answer the majority of questions.

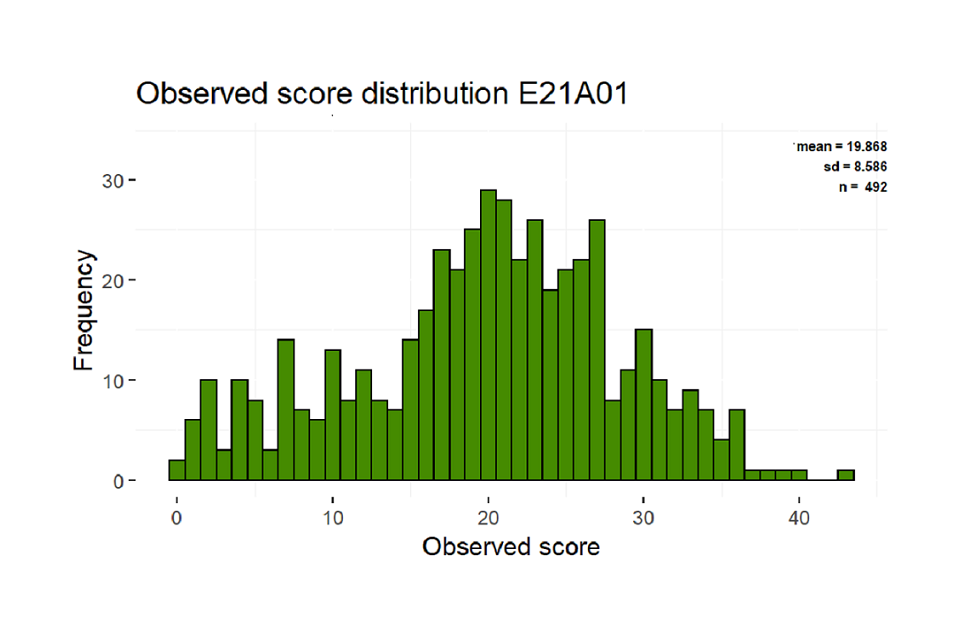

These results were confirmed by the distribution of scores students achieved on the tests. This is shown for one of the tests in Figure 3.1. It is an example of one test booklet only but the distributions were similar for the other tests. The figure shows that students were spread across the range, although no students attained the very highest marks.

Figure 3.1. Score distribution for one of the English tests

In addition, a full item analysis was carried out for each test, in which the difficulty of every question and its discrimination were calculated. These indicated that all the questions had functioned either well or, in a small number of cases, adequately and there was no need to remove any items from the analyses. Therefore, all were retained for the IRT analyses. Additionally, an analysis was conducted to establish if any items had performed markedly differently in 2021 compared with the previous years. Where there are such indications, a formal procedure is followed for reviewing the items to establish whether there could be an external reason for the change. In 2021, no items were removed from the link.

Using the common items, the IRT analyses equated the eight tests. The IRT analyses also used the items common between years[footnote 2] to equate the tests over years, allowing ability estimates for students in all five years to be on the same scale. After this had been done, the results showed that the mean ability scores for students were very similar for all the tests, confirming that the random allocation to tests had been successful. The results also showed that the level of difficulty of the eight tests was fairly consistent, with only small differences between them.

Both the Classical Test Theory results and the IRT results for the English tests showed that these had functioned well to provide good measures of the ability of students, sufficient for estimating averages for the sample as a whole.

Maths

The results of the Classical Test Theory analyses are summarised in Table 3.2. This shows the range of the main test performance statistics for the eight maths tests used.

Table 3.2. Range of Classical Test Theory statistics for the maths tests in 2020

| Classical Test Theory statistic | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Students Taking Each Test Booklet | 513 | 526 |

| Maximum Score Attained (out of 50) | 49 | 50 |

| Average Score Attained | 20.0 | 23.2 |

| Standard Deviation of the Test Booklets | 12.2 | 14.2 |

| Reliability of the Tests (Coefficient Alpha) | 0.90 | 0.91 |

| Average Percentage of Students Attempting Each Item (%) | 83 | 88 |

These results show that the maths tests also functioned well. The maximum score, or one mark short of it, was attained on all booklets. The average scores were, again, slightly less than half marks for most booklets and lower than in recent years. The standard deviation shows that the scores were well spread out, allowing discrimination between the students. This is confirmed by the reliability coefficients which are at a very good level for a maths test of this length and higher than for English, which is usual. Finally, the average percentage of students attempting each item (between 83% and 88%) was lower than in 2020. There are two potential explanations for the reduction in the percentage of students attempting items, firstly it is possible that given the cancellation of formal GCSE examinations students were slightly less engaged with the test and therefore attempted to answer fewer questions; alternatively this could reflect the fact that some students were not taught the full curriculum given the disruption to teaching and learning since the start of the pandemic and were therefore unable to attempt more questions. In 2021, the average percentage of students attempting each item for maths was also lower than that seen for the English test. However, there are more items for students to attempt in the maths test.

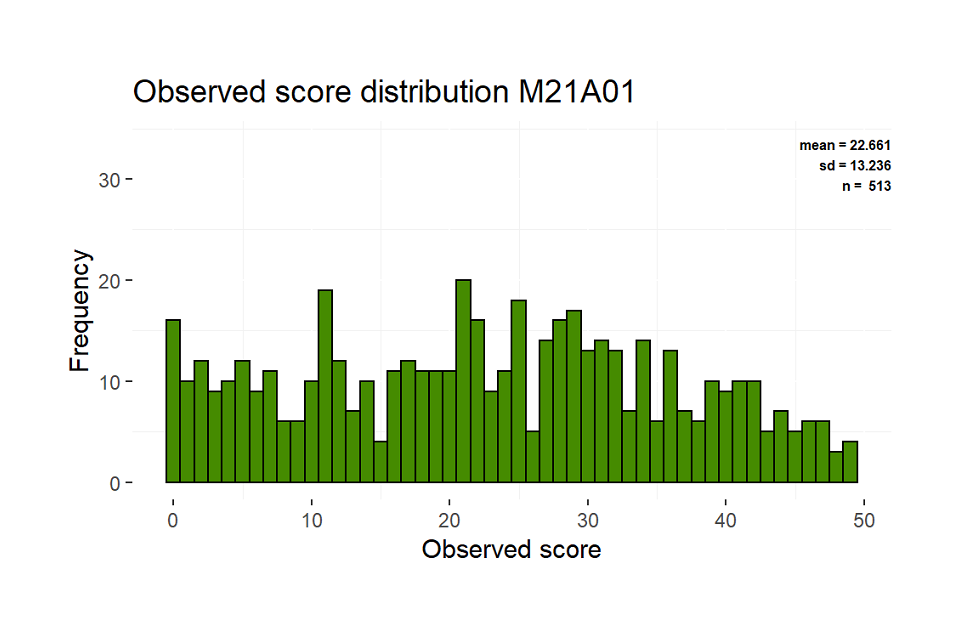

These results were confirmed by the distribution of scores which students achieved on the tests. This is shown for one of the tests in Figure 3.2. The distributions were similar for the other tests. The figure shows that scores were attained over the range of possible marks and that the students were fairly evenly spread over the range.

Figure 3.2. Score distribution for one of the maths tests

In addition, a full item analysis was carried out for each test, in which the difficulty of every question and its discrimination were calculated. These indicated that all the questions had functioned either well or, in a small number of cases, adequately. There was no need to remove any items from the analyses. All were retained for the IRT analyses. Additionally, an analysis was conducted to establish if any items had performed markedly differently in 2021 compared with the previous years. Where there are such indications, a formal procedure is followed for reviewing the items to establish whether there could be an external reason for the change and if there is sufficient evidence to remove the item from the link between years. In 2021, no items were removed from the link.

Using the common items, the IRT analyses equated the eight tests. The IRT analyses also used the items common between years[footnote 3] to equate the tests over years, allowing ability estimates for students in all five years to be on the same scale. After this had been done, the results showed that the mean ability scores for students were similar for all the tests, confirming that the random allocation to tests had been successful. The results also showed that the level of difficulty of the eight tests was fairly consistent, with only small differences between them.

Both the Classical Test Theory results and the IRT results for the maths tests showed that these had functioned well to provide good measures of the ability of students, sufficient for estimating averages for the sample as a whole.

Summary

These initial stages of the analyses, the Classical Test Theory evaluation of test functioning and the Item Response Theory equating of the tests, indicate that the NRT performed as well in 2021 as it had in previous years. This allowed the final stages of the analysis, the estimation of the percentages of students above the same ability thresholds as in 2017 and the calculation of their precision, to be undertaken with confidence. These are described in Sections 4 and 5 for English and maths respectively.

4. Performance in English in 2021

The objective of the National Reference Test (NRT) is to get precise estimates of the percentages of students each year achieving at a level equivalent to three key GCSE grades in 2017: these key grades are 4, 5 and 7. For the NRT in 2017, these baseline percentages were established from the 2017 GCSE population percentages. The NRT ability distribution, based on the Item Response Theory (IRT) analysis, was then used to establish the ability thresholds which corresponded to those percentages. From 2018 onwards, the thresholds correspond to the same level of student ability as the thresholds established in 2017, thus allowing us to estimate the percentage of students above each of those thresholds and track performance over time. Alongside this, based on the sample achieved and the reliability of the tests, we are able to model the level of precision with which the proportion of students achieving the ability thresholds can be measured. The target for the NRT is to achieve a 95% confidence interval of plus or minus no more than 1.5 percentage points from the estimate at each ability threshold.

Ofqual provided the percentages of students at or above the three relevant grades (grades 4, 5 and 7) taken from the 2017 GCSE population. These are shown in Table 4.1. These percentages were mapped to three ability threshold scores in the NRT in 2017.

Table 4.1. English 2017 NRT baseline thresholds

| Threshold | Percentage of students above threshold from 2017 GCSE |

|---|---|

| Grade 7 and above | 16.8 |

| Grade 5 and above | 53.3 |

| Grade 4 and above | 69.9 |

In 2021, the NRT data for the years 2017 to 2021 were analysed together using IRT modelling techniques. By analysing all the data concurrently, ability distributions could be produced for the samples for each year on the same scale. The percentages of students at each of the three GCSE grade boundaries, fixed on the 2017 distribution, could then be mapped onto the distributions for the subsequent years to produce estimates of the percentage of students at the same level of ability in those years. For example, the percentage of students at the ‘Grade 4 and above’ threshold in the 2017 GCSE population was 69.9%. This was mapped onto the 2017 distribution to read off an ability value at that grade boundary. The same ability value on the 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021 distributions can then be found, and the percentage of students at this threshold or above in those years can be established. In this way, we are able to estimate the percentage of students at the same level of ability as represented in the 2017 GCSE population for each year of the NRT going forward. The precision of these estimates is dependent on both the sample achieved and the reliability of the tests as measures.

Table 4.2 presents the percentages of students achieving above the specified grade boundaries for the years 2017 to 2021. Confidence intervals for percentages are provided in brackets alongside the estimates. This is important as it shows that, although there have been changes in performance, these are often within the confidence intervals. The statistical interpretation of the differences is discussed below.

Table 4.2. Estimated percentages at grade boundaries in English

| Year | Estimated percentages at Grade 4 and above | Estimated percentages at Grade 5 and above | Estimated percentages at Grade 7 and above |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 69.9 (67.5 - 72.4) | 53.3 (50.8 - 55.8) | 16.8 (15.5 - 18.1) |

| 2018 | 68.9 (66.5 - 71.3) | 52.5 (50.2 - 54.8) | 16.7 (15.1 - 18.4) |

| 2019 | 65.8 (63.3 - 68.4) | 49.5 (46.9 - 52.1) | 16.3 (15.0 - 17.7) |

| 2020 | 67.5 (65.3 - 69.7) | 51.5 (49.6 - 53.4) | 17.5 (16.2 - 18.8) |

| 2021 | 66.8 (64.1 - 69.5) | 51.6 (49.1 - 54.0) | 18.7 (16.9 - 20.5) |

The 2017 figures in the table above are based on the NRT study, rather than the 2017 GCSE percentages. Note that, because of the way in which they have been computed, they match closely with the GCSE percentages. The confidence intervals for them reflect the fact that the NRT 2017 outcomes carry the statistical error inherent in a sample survey, as per the subsequent years.

Since the percentages for previous years have been re-estimated following the concurrent calibration with the 2021 data, these figures differ slightly from those reported in previous years. Some degree of variation is expected given the addition of more data, and the differences seen are small.

Table 4.3 shows the half widths of the confidence intervals. The confidence intervals for 2021 are wider than for previous years by around 0.5 percentage points, reflecting the smaller sample size this year. The estimates of the precision for earlier years of the NRT have also changed relative to those reported in previous years, with an increase in the width of the confidence intervals at the two lower grade thresholds.

Table 4.3 English NRT half width of confidence intervals each year

| Year | Half width of confidence intervals: Grade 4 and above | Half width of confidence intervals: Grade 5 and above | Half width of confidence intervals: Grade 7 and above |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| 2018 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.7 |

| 2019 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.4 |

| 2020 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

| 2021 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1.8 |

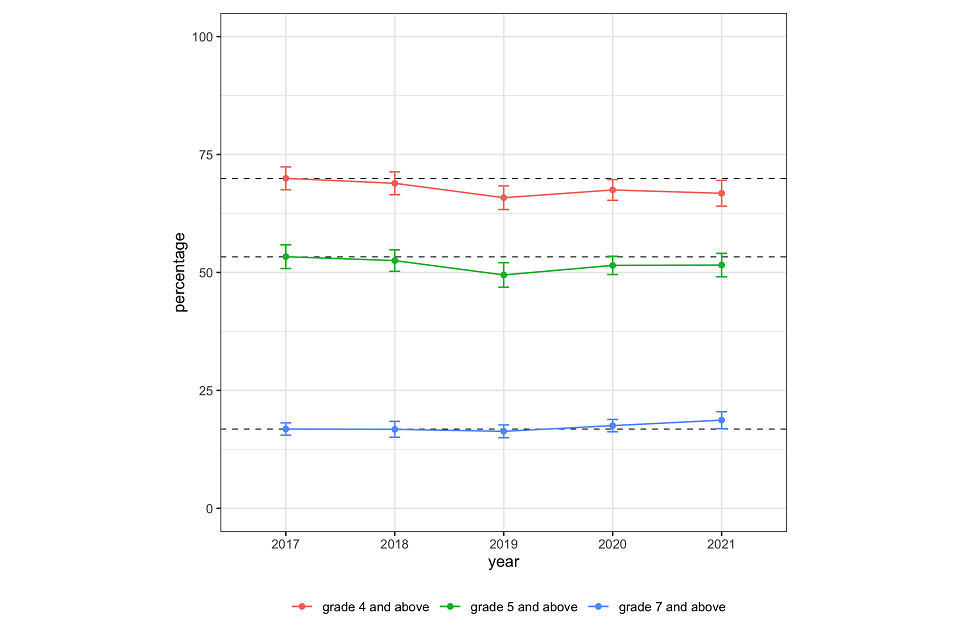

Figure 4.1 presents 95% confidence intervals around the percentages achieving at least the specified grade boundary in 2021, as compared with previous years and the 2017 population baseline percentages. The 2017 population percentages are represented as dotted lines and the trend lines across years as solid lines. This format has been used to encourage the reader to compare the point estimate confidence bands for each year with the 2017 baseline population percentages, bearing in mind the confidence intervals.

Figure 4.1. Long term changes in NRT English over time from 2017 baseline

The chart shows that performance in English is broadly similar to 2020. There had previously been a small decline in the percentage of students achieving at-or-above both grades 4 and 5 from the baseline in 2017 to 2019, but 2020 had seen an upturn in performance, bringing performance much closer to that seen in 2017. This performance has then remained stable in 2021. At grade 7 and above, performance has been relatively consistent across the years, with a slight decline in 2019 followed by a slight improvement in 2020, which has continued into 2021. The slight increase this year in the proportion at grade 7 and above and the slight decrease at grade 4 and above indicates a widening of the underlying ability distribution relative to previous years.

A key question arising for the NRT results in a given year is to determine if differences in outcomes across the years are statistically significant. For the NRT, several comparisons could be made between different pairs of years at different grade boundaries, and this gives rise to a danger that changes arising by chance may seem real. Hence, the criteria for significance that have been used are adjusted for multiple comparisons. (For more information, see Appendix A.)

The research question NFER was asked to address is to compare the performance in 2021 with the performance in 2020 at each of the three grade boundaries. Adjusting for three comparisons, the NRT English data shows that there are no significant differences in performance between 2020 and 2021 at any of the three grade boundaries[footnote 4]

5. Performance in maths in 2021

The objective of the National Reference Test is to get precise estimates of the percentages of students each year achieving at a level equivalent to three key GCSE grades in 2017: these key grades are 4, 5 and 7. For the NRT in 2017, these baseline percentages were established from the 2017 GCSE population percentages. The NRT ability distribution, based on the Item Response Theory (IRT) analysis, was then used to establish the ability scores which corresponded to those percentages. From 2018 onwards, the thresholds correspond to the same level of student ability as the thresholds established in 2017, thus allowing us to estimate the percentage of students above each of those thresholds and track performance over time. Alongside this, based on the sample achieved and the reliability of the tests, we are able to model the level of precision with which the proportion of students achieving the ability scores can be measured. The target for the NRT is to achieve a 95% confidence interval of plus or minus no more than 1.5 percentage points from the estimate at each ability threshold.

Ofqual provided the percentages of students at or above three relevant grades (grades 4, 5 and 7) taken from the 2017 GCSE population. These are shown in Table 5.1. These percentages were mapped to three ability threshold scores in the NRT in 2017.

Table 5.1. Maths 2017 NRT baseline thresholds

| Threshold | Percentage of students above threshold from 2017 GCSE |

|---|---|

| Grade 7 and above | 19.9 |

| Grade 5 and above | 49.7 |

| Grade 4 and above | 70.7 |

In 2021, the NRT data for the years 2017 to 2021 were analysed together using IRT modelling techniques. By analysing all the data concurrently, ability distributions could be produced for the 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020 samples on the same scale. The percentages of students at each of the three GCSE grade boundaries, fixed on the 2017 distribution, could then be mapped onto the distributions for the subsequent years to produce estimates of the percentage of students at the same level of ability in those years. For example, the percentage of students at the ‘Grade 4 and above’ threshold in the 2017 GCSE population was 70.7%. This was mapped onto the 2017 distribution to read off an ability value equivalent to that grade boundary. The same ability value on the 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021 distributions can then be found, and the percentage of students at this threshold or above in those years can be established. In this way, we are able to estimate the percentage of students at the same level of ability as represented in the 2017 GCSE population for each year of the NRT going forward. The precision of these estimates is dependent on both the sample achieved and the reliability of the tests as measures.

Table 5.2 presents the percentages of students achieving above the specified grade boundaries for the years 2017 to 2021. Confidence intervals for percentages are provided in brackets alongside the estimates. This is important as it shows that although there have been changes in performance, these are often within the confidence intervals. The statistical interpretation of the differences is discussed below.

Table 5.2. Estimated percentages at grade boundaries in maths

| Year | Estimated percentages at Grade 4 and above | Estimated percentages at Grade 5 and above | Estimated percentages at Grade 7 and above |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 70.7 (69.4 - 72.1) | 49.7 (48.1 - 51.3) | 19.9 (18.5 - 21.3) |

| 2018 | 73.3 (71.8 - 74.8) | 52.4 (50.8 - 54.1) | 21.5 (20.2 - 22.8) |

| 2019 | 73.5 (72.2 - 74.8) | 51.9 (50.1 - 53.7) | 22.7 (21.4 - 24.0) |

| 2020 | 74.0 (72.7 - 75.3) | 54.4 (53.0 - 55.9) | 24.0 (22.7- 25.4) |

| 2021 | 69.6 (67.5 - 71.6) | 49.2 (47.1 - 51.3) | 21.0 (19.2 - 22.8) |

The 2017 figures in the table above are based on the NRT study, rather than the 2017 GCSE percentages. Note that, because of the way in which they have been computed, they match closely with the GCSE percentages. The confidence intervals for them reflect the fact that the NRT 2017 outcomes carry the statistical error inherent in a sample survey, as per the subsequent years.

Since the percentages for previous years have been re-estimated following the concurrent calibration with the 2021 data, these figures differ slightly from those reported in previous years. Some degree of variation is expected given the addition of more data, and the differences seen are small.

Table 5.3 shows the half widths of the confidence intervals. The confidence intervals for 2021 are wider than for previous years by around 0.5-0.7 percentage points, reflecting the smaller sample size this year. Any changes in the estimates of precision for the earlier years of the NRT due to the addition of 2021 data are minimal.

Table 5.3. Maths NRT half width of confidence intervals each year

| Year | Half width of confidence intervals Grade 4 and above | Half width of confidence intervals Grade 5 and above | Half width of confidence intervals Grade 7 and above |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| 2018 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| 2019 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| 2020 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| 2021 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

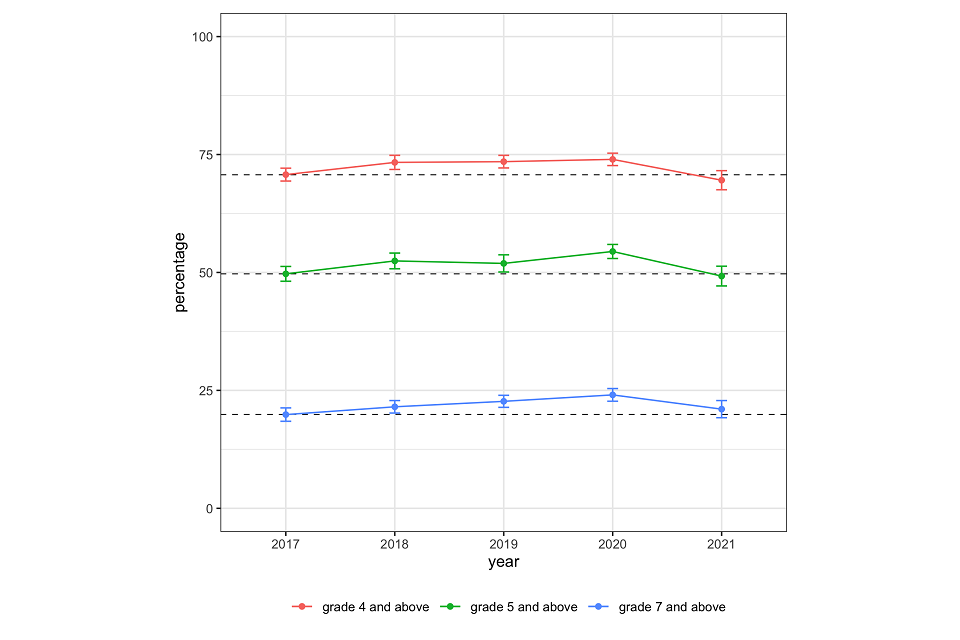

Figure 5.1 presents 95% confidence intervals around the percentages achieving at least the specified grade boundary in 2021, as compared to previous years and the 2017 population baseline percentages. The 2017 population percentages are represented as dotted lines and the trend lines across years as solid lines. This format has been used to encourage the reader to compare the point estimate confidence bands for each year with the 2017 baseline population percentages, bearing in mind the confidence intervals.

Figure 5.1. Long term changes in NRT maths over time from 2017 baseline

The chart shows a relatively steady increase in the percentage of students achieving at-or-above all three grade boundaries from 2017 to 2020, followed by a sharp drop in 2021, back to around the 2017 level of performance. A key question arising for the NRT results in a given year is to determine if differences in outcomes across the years are statistically significant. For the NRT, several comparisons could be made and this gives rise to a danger that changes arising by chance may seem real. Hence, the criteria for significance that have been used are adjusted for multiple comparisons. (For more information, see Appendix A.)

The research question NFER was asked to address is to compare the performance in 2021 with the performance in 2020 at each of the three grade boundaries. Adjusting for three comparisons, the NRT maths data shows that there has been a statistically significant drop in performance between 2020 and 2021 at all three grade boundaries. The differences at grades 4 and 5 and above are significant at the 1% level of significance, whereas the difference at grade 7 and above is significant at the 5% level. [footnote 5]

6. Appendix A: A brief summary of the NRT

English

The English test takes one hour to administer and follows the curriculum for the reformed GCSE in English language. In each of the eight English test booklets, there are two components; the first is a reading test and the second a writing test. Each component carries 25 marks and students are advised to spend broadly equal time on each component.

The reading test is based on an extract from a longer prose text, or two shorter extracts from different texts. Students are asked five, six or seven questions that refer to the extract(s). Some questions of one to four marks require short responses or require the student to select a response from options provided. In each booklet, the reading test also includes a 6-mark question and a 10-mark question, where longer, more in-depth responses need to be given. These focus on analysis and evaluation of particular aspects of the text or a comparison between texts.

The writing test is a single, 25-mark task. This is an extended piece of writing, responding to a stimulus. For example, students may be asked to describe, narrate, give and respond to information, argue, explain or instruct.

Maths

For maths, a separate sample of students is also given one hour to complete the test. The test includes questions on number, algebra, geometry and measures, ratio and proportion, and statistics and probability – the same curriculum as the reformed GCSE. Each of the eight test booklets has 13 or 14 questions with a total of 50 marks and each student takes just one of the test booklets.

Analysis

The analysis process followed a sequence of steps. Initially, the tests were analysed using Classical Test Theory to establish that they had performed well, with appropriate difficulty and good levels of reliability. The subsequent analyses used Item Response Theory techniques to link all the tests together from 2017 to 2021 and estimate the ability of all the students on a common scale for each subject for each year, independent of the test or items they had taken. These ability estimates were then used for calculating the ability level at the percentiles associated with the GCSE grade boundaries in 2017 and mapping these onto the distributions for subsequent years to generate percentile estimates for those years.

Multiple Comparisons

The statistical significance of the difference between two percentages estimated in two years, say 2020 and 2021, may be approached with a two-sample t-statistic. Because of the huge number of degrees of freedom, the value can be compared with the standard normal distribution rather than the t-distribution. For a comparison of two percentages, say the percentage of students at grade 4 or higher between two years, the critical value at a confidence level of 0.05 (5%) would usually be 1.96. However, since there are three grade thresholds across multiple years, there are a number of comparisons which could be made (up to 30 if all pairs of years were compared across all three grade boundaries). As the number of simultaneous comparisons grows, the probability that some of them are significant by chance rapidly increases. To guarantee that the chosen level of significance is guaranteed overall, we have implemented an adjustment for multiple comparisons.

-

The number of independent schools participating in the NRT has varied across the years: seven in 2017 and 2018, nine in 2019 and four in 2020 (the ‘establishment type’ information included in the sampling frame for each school was obtained from Get Information About Schools). Students from independent schools have historically comprised around one per cent of the achieved sample (both weighted and unweighted). ↩

-

The 2021 version of the NRT contained the same items as those used in the tests from 2017 to 2020. A very small number of items are removed from the link from one year to the next if performance has changed on that item relative to others and there is evidence that this is likely to be due to a cause other than a genuine change in performance (for example, a change in the way the item was marked). ↩

-

The 2021 version of the NRT contained the same items as those used in the tests from 2017 to 2020. A very small number of items are removed from the link from one year to the next if performance has changed on that item relative to others and there is evidence that this is likely to be due to a cause other than a genuine change in performance (for example, a change in the way the item was marked). ↩

-

The results of a given year’s NRT can be compared with the NRT results from a previous year (both are sample surveys, and the statistical error is therefore reflected in confidence intervals for each administration) or with the GCSE percentages of 2017, regarded as external constants. The 2018 Results Digest reported comparisons with the GCSE 2017 population percentages. However, in order to make ongoing comparisons from year to year it was decided, for 2019 onwards, that comparing the outcomes between NRT studies (For example, making statistical comparisons with the 2017 NRT study, rather than 2017 GCSE percentages) would be more informative. ↩

-

The results of a given year’s NRT can be compared with the NRT results from a previous year (both are sample surveys, and the statistical error is therefore reflected in confidence intervals for each administration) or with the GCSE percentages of 2017, regarded as external constants. The 2018 Results Digest reported comparisons with the GCSE 2017 population percentages. However, in order to make ongoing comparisons from year to year it was decided for 2019 onwards that comparing the outcomes between NRT studies (For example, making statistical comparisons with the 2017 NRT study, rather than 2017 GCSE percentages) would be more informative. ↩