The road not taken: drivers of course selection (HTML)

Published 30 March 2021

The road not taken: the drivers of course selection

The determinants and consequences of post-16 education choices

Research report

March 2021

Executive summary

It’s more important than ever to consider how students from all backgrounds can access high-quality academic and technical education, due to the severe disruption to their schooling and the level of economic shock experienced during the pandemic.

A crucial point to consider is what happens when young people reach the age of 16. This is when students make decisions about their education and choose what type of course to follow, as well as the level and subjects that they would like to study. These choices are pivotal as they can strongly influence their future educational opportunities, employment prospects and even how much they will go on to earn.

This report uses a mixed-methods approach to investigate the socio-economic differences in post-16 choices, factors driving these differences and the likely social mobility consequences of picking the most popular options. We have achieved this by using administrative data linking the education and earnings of young people who took post-16 qualifications in the mid-2000s.

In addition, to better understand the key behaviours driving the choices, we undertook in-depth interviews with senior leaders, curriculum managers, teachers and learners from 5 learning providers. This has been supplemented by a review of relevant literature and survey evidence.

Definitions and data

Academic qualifications/routes: For this report, we have focused exclusively on A levels.

Technical qualifications/routes: We have focused on vocational or specialised applied learning such as BTECs and apprenticeships (a very broad range of qualifications).

High-/low-earning courses: We grouped academic and technical routes by subject and level and ranked them by average earnings among young people who took that pathway. This allows us to see which courses are in the top 50% and 25% of earnings amongst students, and how this varies by socio-economic background. For brevity’s sake, we often refer to “x% of courses” to mean “x% of students on courses.”

Socio-economic disadvantage: We created an index of socio-economic disadvantage by combining individual measures of disadvantage and other area-based indicators.

Time frame: We focused on young people who took their post-16 qualifications between 2002 and 2007. This allowed us to follow them into the labour market and observe their earnings as they started their prime earning phase in their late 20s. We also examined socio-economic differences among more recent cohorts. The patterns are very similar.

Key findings

The highest earning routes are A levels or a combination of A levels and technical courses

Academic courses are associated with the highest earnings. 80% of A level courses are ranked in the top 25% of earnings. This partly reflects the fact that academic courses often facilitate access to higher education.

Courses combining academic and technical qualifications are relatively high-earning too, with 70% of students ending up in jobs ranked in the top 50% of earnings.

Technical qualifications are mostly associated with low earnings. 62% of classroom-based technical qualifications and 40% of apprenticeships are in the bottom 25% of earnings.

The small number of high-earning technical routes are mostly taken by men

The technical qualifications with highest earnings potential are Level 3, particularly Level 3 apprenticeships.

Men are more likely to take courses in higher-earning subject areas, such as engineering, construction and planning. Women are more likely to study subjects associated with low earnings, such as retail, commerce, health, care and public services.

Young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to choose low-earning courses (particularly women)

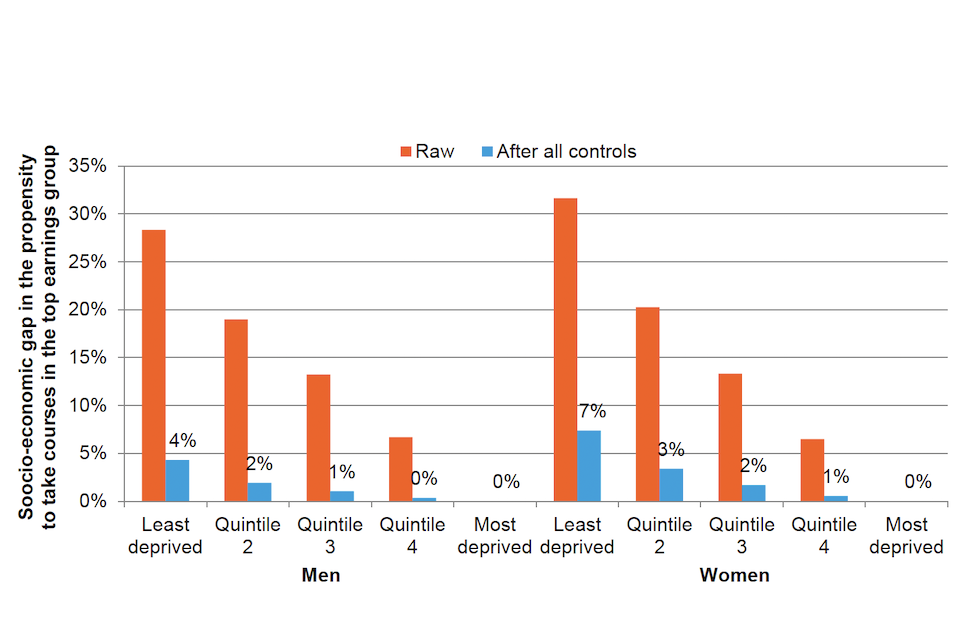

The most privileged men are 28 percentage points more likely to take a course in the top 25% of earnings than men in the most deprived group; the equivalent gap for women is 31 percentage points.

Men and women with ‘just above average’ levels of deprivation are 20–25 percentage points less likely to take a course in the top 25% of earnings than the most affluent group.

About 50% of disadvantaged women take low-earning courses ranked in the bottom 25% of earnings, which compares with about 31% of disadvantaged men.

Women are 10 percentage points more likely than men to choose the courses in technical education that pay the least well.

Some disadvantaged groups are more likely to choose low earning courses

Prior attainment mostly explains why young people choose the highest-earning courses. However some groups are more likely to choose the lowest paying routes, regardless of their achievements.

High achieving disadvantaged students are less likely to choose the higher-earning academic routes than students from privileged backgrounds.

Disadvantaged women with middle and low levels of prior attainment are more likely to choose low-earning technical courses than women from privileged backgrounds.

Course choices explain more of the earnings inequalities for women than for men

Disadvantage has persistent effects on early-career earnings, even after controlling for prior attainment. Men’s choice of subject or course does not make this any worse. However, there is a further ‘earnings penalty’ for disadvantaged women of around 4 to 5 percentage points linked to their subject and course choices.

Those choosing low-earning courses including disadvantaged Black Caribbean students and disadvantaged White British women

Only 27% of women and 22% of men from disadvantaged Black Caribbean backgrounds took courses in the top 50% of earnings.

Only 24% women and 33% men from disadvantaged White British backgrounds took courses in the top 50% of earnings.

There are significant gaps in the provision of careers guidance

Only 3 in 5 young people report receiving any career guidance before the age of 16. Learners and providers also feel that much less information is provided about technical routes than academic routes. This is despite the implementation in 2018 of the ‘Baker Clause’, which stipulates that all schools must allow colleges and training providers access to all pupils in years 8–13 to discuss non-academic routes.

Young people taking higher-level courses are usually better informed about education pathways and other opportunities open to them.

Disadvantaged young people are more likely to be disappointed by their choices

Interest and enjoyment are important motivations for many students choosing courses. Higher-achieving learners are typically more able to pick a course they enjoy. Low-achieving learners frequently find some choice replaced by mandatory, corrective content so they enjoy less freedom.

Aspirations are generally high. However young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to experience disappointment because of low attainment at the end of their course. As a result, they are more likely to find themselves on low-earning routes that they hadn’t intended to take.

Gender norms remain pervasive

There are strong gender disparities in subjects such as engineering, IT, beauty and childcare. Teachers say that this replicates the gender bias present in the various industries. They also note that course choice can be strongly influenced by a student’s role models.

Geography and the availability of courses play an important role

The cost of travel and how long it takes to get somewhere can influence a learner’s choice of provider and course. This is particularly the case for apprentices who need to travel to both their place of study and work.

Disadvantaged students are more likely to take higher level courses (for example, Level 3 courses) in areas such as London where there is a wide availability of school sixth forms. They are much less likely to take these higher-earning courses in places such as the north-west and north-east of England, where there is the lowest availability of school sixth forms.

Policy implications

Focus on educational inequalities up to 16 and target specific disadvantaged groups

Prior educational attainment has a large impact on choices, so it’s important to reduce inequalities before children reach 16. Educational progress is likely to be more restricted for students whose attainment was poor throughout school.

Specific groups are being penalised by their choices and could benefit from extra careers guidance and support. Beneficiaries could include disadvantaged women with low or average prior attainment; disadvantaged Black Caribbeans; and disadvantaged White British women.

Better guidance is needed on technical routes before the age of 16, particularly for disadvantaged pupils

Welcome steps are being made to improve careers guidance. There has been widespread implementation of the Gatsby principles which are a series of benchmarks created by the Gatsby Charitable Foundation and adopted as part of the government’s career strategy for schools and colleges. Local careers hubs have also been established.

The white paper, ‘Skills for jobs: lifelong learning for opportunity and growth’, proposes toughening the so-called ‘Baker Clause’ which should improve students’ knowledge of non- academic routes. The white paper, published in January 2021, also proposes presenting more data on the returns for different qualifications.

The challenges faced by disadvantaged pupils still need to be addressed. It is crucial that the government provides the necessary targeted resources to support them.

Interventions need to be trialled to target the key drivers of behaviour

It would be valuable to explore the impact of gender norms and role models. Trials could also explore parental influences and the benefits of work experience for technical occupations.

Look at how to promote progression, and combine academic and technical courses

The recent white paper focuses on the potential strengths of new T levels (2 year courses which are equivalent to 3 A levels). These courses have been developed in collaboration with employers and businesses and combine classroom learning with ‘on-the-job’ experience. They should enable more young people to gain Level 4 and 5 technical qualifications. Research shows that students combining technical and academic qualifications have relatively high earnings as the skills gained are valued in the labour market. Another benefit is that students can switch between routes as they establish what suits them best.

It’s very positive that more young people will be able to progress to Level 4 and 5. However, promoting social mobility will also require supporting students from Level 2 to Level 3, so that they can then move on to the higher technical qualifications. Targeted support and flexible provisions for disadvantaged young people is crucial to avoid future educational inequalities opening up at Levels 4 and 5.

16-year-olds with low attainment often require compulsory learning to fix knowledge gaps in core maths, English and IT. Corrective learning should be contextualised with vocational subjects to provide interest.

Help with travel and easy availability of higher-level courses can encourage take-up

Disadvantaged students who are mid-attaining are more likely to take Level 3 qualifications if they can study at a local school sixth form.

Disadvantaged pupils can be discouraged from taking certain courses or apprenticeships if it’s expensive for them to get there. Help with travel costs can remove this barrier.

1. Introduction

It’s more important than ever to consider how students from all backgrounds can access high-quality academic and technical education, due to the severe disruption to their schooling and the level of economic shock experienced during the pandemic.

At the age of 16, young people make critical decisions about their education. They can choose between academic routes, technical courses, a blended approach or an apprenticeship. They can select what level of course to take, including Level 3 (A level equivalent) and Level 2 (GCSE equivalent) or below. They can choose whether to study in school sixth forms, sixth form colleges, further education colleges or with other providers. They must also decide what to study. Often these choices are bundled together, with sixth forms more likely to offer A levels and further education colleges more likely to offer technical courses.

The choices that students make are influenced by what’s on offer in their area and heavily shaped by their prior educational attainment, with A levels or Level 3 courses only available to them if they’ve got good GCSE results.

The path they take could determine the educational opportunities available to them at the end of the course, their employment prospects and even their future earnings. The choices also have the potential to impact on social mobility.

Existing evidence shows that young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to study at further education colleges and choose lower-level courses.[footnote 1] Clear evidence has also emerged of differences in earnings that are linked to the subject taken at higher education level, as well as vocational courses and apprenticeships.[footnote 2]

There is burgeoning evidence that young people from poorer families often ‘under-match’ on university choices (do not apply for competitive universities that they are academically qualified for). Important explanations given for this phenomenon include the effects of local availability and school or neighbourhood contexts.[footnote 3]

This report investigates the drivers of socio-economic differences in post-16 course choices and their likely social mobility consequences. We do this through a mixed-methods approach. This combines new quantitative analysis of linked education-employment administrative data; qualitative analysis; case studies based on in-depth discussions with providers and learners; and a review of relevant literature, survey data and policy options.

In section 2, we start by using linked data to analyse the courses associated with the highest levels of earnings in the labour market. This includes the broad route (academic, technical, apprenticeship or a combination), level of study and subject(s) studied. This provides a typology of whether courses are high- or low-earning, with courses split into one of 4 earnings groups.

In section 3, we detail the socio-economic differences in young people’s likelihood of taking high- and low-earning courses. We focus mostly on technical and apprenticeship courses, given that young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to take these courses. We analyse how much of these socio-economic differences can be explained by prior attainment and pupil characteristics and how much can be explained through post-16 choices. We also detail the likely social mobility implications of post-16 choices by examining differences in early- career earnings (when individuals are aged 25–30).

In section 4, we examine the behavioural factors driving post-16 choices. This includes differences in capabilities, such as prior attainment and knowledge; geographical availability of different courses, information and careers guidance; and aspirations and motivations. The analysis draws on detailed interviews and testimony from a range of learners and providers.

In the final section, we discuss the policy implications of this report’s findings. This includes examining the best ways to tackle inequalities, including assessing the design of the educational system and careers guidance for young people, as well as reflections on the recent white paper on further education and skills.[footnote 4]

Throughout the report, we also draw on a literature review of the factors shaping aspirations and motivations to take technical courses, which is published as a separate annex.

2. Methodology: defining high- and low-earning courses

To investigate the social mobility implications of course choices, we have analysed new administrative data linking the education and earnings records of young people over time. This enables us to assess the socio-economic differences, the factors driving these differences and their implications for earnings in the labour market.

In this section, we outline the data and explain how we use it to address our research questions. We focus on our methods for categorising the education options into 4 groups based on their earnings potential.

Key findings

Academic course routes are associated with the highest earnings; 80% of A level-focused course routes are in the top 25% of earnings.

Course routes combining academic and technical qualifications are relatively high-earning too, with 70% in the top 50% of earnings.

Technical qualifications are mostly associated with low earnings, with 62% of classroom- based technical qualifications and 40% of apprenticeships in the bottom 25% of earnings.

The small number of technical qualifications with higher earnings potential are at Level 3, particularly Level 3 apprenticeships.

Women from low socio-economic backgrounds are much more likely to take technical subjects associated with low earnings, such as retail, commerce, health, care and public services. Men are much more likely to take higher-earning subjects, such as engineering, construction and planning.

Data and sample selection

We use data on the choices and earnings of individuals who completed their GCSEs in England between 2001/02 and 2004/05. We necessarily focus on these older cohorts so that we can track their actual earnings up to age 30. To ensure that this analysis is still relevant today, we also show what the socio-economic differences in post-16 course choices would look like for more recent cohorts, if the earnings potential of different courses were unchanged over time.

This sample includes about 2.5 million young people over 4 years; or about 600,000 to 650,000 per year (see Appendix Table A1 for full details).

Education and earnings information

We use the Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) dataset, which provides us with information on background characteristics,[footnote 5] post-16 education choices and labour market earnings of individuals. This dataset links 3 sources of data:

-

The National Pupil Database (NPD), which contains information on pupil characteristics (such as eligibility for free school meals and ethnicity) and on school achievement from Key Stage 1 (KS1) through to Key Stage 4 (KS4) and Key Stage 5 (KS5) where applicable

-

Individualised Learner Record (ILR) data collected by publicly funded colleges, training organisations, local authorities and other further education (FE) providers, which includes technical education records

-

Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) earnings data between 2010/11 and 2016/17, which provides a measure of annual employment earnings (from PAYE records) for ages 25 to 30;[footnote 6] earnings data is missing for individuals who are not in employment, and we do not observe hours worked in the data

The sample used in analysis

In our analysis, we focus on students who continued into post-16 education after completing their GCSEs. An individual must have either KS5 NPD records and/or ILR data as well as earnings data to be included in our analysis sample. The final sample is about 70% of the original GCSE cohort (see Appendix Table A2 for further details).[footnote 7]

Categorising post-16 course choices

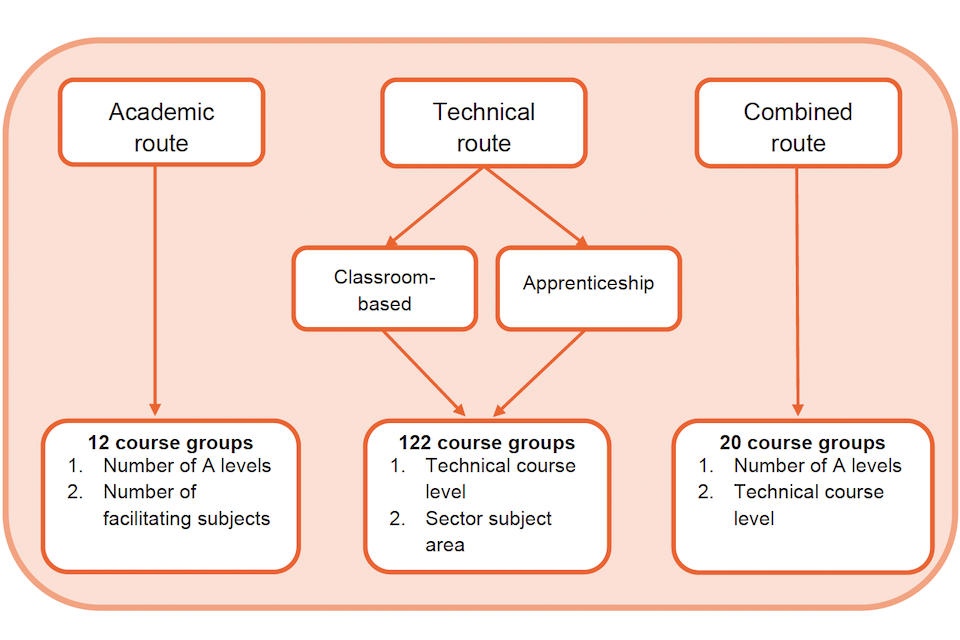

At age 16, young people can make countless educational choices. They can study academic or technical qualifications in a range of subjects and at various levels. To effectively analyse these choices, we have classified all possible post-16 educational choices into a finite number of course groups using the following set of criteria (Figure 2.1 illustrates the course groups we define):

First, we classify each individual’s post-16 educational choices into one of 3 routes:

- academic route: A levels

- technical route: classroom-based technical qualifications or an apprenticeship

- combined route: a combination of academic and technical qualifications

We further classify each of these 3 routes based on the following rules.

For the academic route, we define 12 distinct course groups using a combination of the number of A levels studied and the number of these A levels that are in facilitating subjects:[footnote 8]

- we group the number of A levels into 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more

- the number of facilitating subjects is sorted into 0, 1, and 2 or more

For the technical route, we separate apprenticeships and classroom-based courses and then create 61 course groups for each of these routes based on the course level and subject area studied:

- we group each course into Level 0, Level 1, Level 2, Level 3, and Level 4 and above

- we classify each course above Level 0 into one of 15 Ofqual-defined subject areas[footnote 9]

For the combined route, we define 20 course groups by the number of A levels and the highest level of technical course studied:

- we group the number of A levels into 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more

- we group each technical course into Level 0, Level 1, Level 2, Level 3, and Level 4 and above

In Figure 2.1 we illustrate this categorisation of post-16 choices into course groups. We provide a full list of the course groups and the number of individuals in each group in Appendix Table A3.

We focus on courses taken up to Level 3 to focus attention on options generally taken by young people between ages 16 and 18. However, the earnings associated with each of these course choices will clearly also be determined by the extent to which they allow young people to progress to different types and higher levels of qualifications.

A potential issue with these criteria is which course to focus on for individuals who study multiple technical courses. In such instances, we focus on the highest-level technical course that the individual begins between the ages of 16 and 20. Furthermore, for individuals who have taken multiple courses at their highest level, we give precedence to apprenticeships over classroom-based courses, and then to the first course started after the individual turned 16.

Figure 2.1: Post-16 education course groups

Categorising course groups by earnings

The criteria, set out above, classify each potential set of post-16 choices into one of 154 course groups. However, it is necessary to further categorise these groups to make our analysis tractable.

We categorised each of the post-16 education course groups illustrated in Figure 2.1 based on their earnings potential. Specifically, we calculated average earnings between the ages of 25 and 30 for individuals in each course group and then categorised course groups with similar earnings potential. In total, we defined 4 earnings categories.

In Table 2.1 we show the interquartile range of the earnings associated with each of the 4 earnings groups. We set the earnings thresholds so that each group contains roughly 25% of the individuals in our sample.

Table 2.1 shows that there are large differences between our defined earnings groups. While individuals who select a course in the low earnings groups have annual average earnings of

£11,200 between the ages of 25 and 30, those who take a course in the high-earnings groups have annual average earnings of £25,500.

The earnings categories are defined with men and women considered together. This allows us to examine gender differences in the likelihood of young people taking post-16 courses associated with high and low earnings.

Table 2.1: Interquartile range of average annual earnings between the ages of 25 and 30 for each earnings group

| Earnings group | 25th percentile | Median | 75th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | £10,100 | £11,200 | £12,100 |

| Middle-lower | £15,000 | £16,700 | £17,300 |

| Middle-upper | £19,200 | £21,100 | £21,600 |

| High | £23,800 | £25,500 | £26,600 |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. Figures are rounded to the nearest hundred.

Low and high-earnings course groups

There is a great deal of variation in the earnings associated with different educational routes. In Figure 2.2 we show the share of learners in each earnings group from the main post-16 educational routes.

First, the left-most bar in Figure 2.2 shows that individuals are roughly evenly spread across the 4 earnings groups. The share is not exactly 25% across groups as some course groups can be quite large. As one might expect, there is not an even share of individuals in each earnings group across the different routes. Students in the A level and combined routes are far more likely to be in higher earnings groups. Almost 80% of students on the A level route are in the highest earnings group, and nearly 100% of individuals on this route are in the top 2 (high and middle-upper) earnings groups. The high earnings associated with A level routes will partly reflect the fact that academic courses facilitate access to higher education.

Almost 70% of students taking courses in the combined route are in these top 2 earnings groups. In contrast, the majority of individuals who have taken technical qualifications (either classroom-based or apprenticeships) are in the 2 lowest earnings groups (middle-lower and low). Almost 62% of students on the classroom-based route and 40% of apprentices are in the bottom earnings group.

Figure 2.2: Percentage of learners taking post-16 courses in each earnings group by education route

| Earnings group | All learners | Academic | Technical classroom | Apprenticeship | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 26% | 79% | - | 14% | 24% |

| Middle upper | 23% | 20% | - | 12% | 46% |

| Middle lower | 27% | - | 35% | 33% | 30% |

| Low | 24% | - | 62% | 40% | - |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. All cell sizes are greater than 1,000.

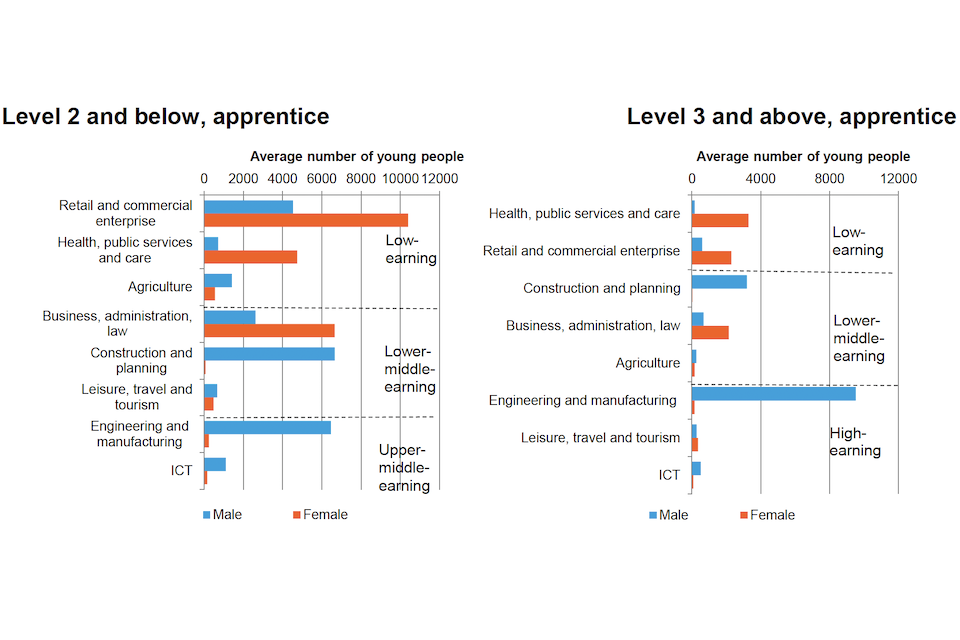

While technical routes are on average associated with lower earnings, there are certain technical courses that do lead to high earnings. In Figure 2.3, we divide technical routes by their level and show the share of students in each earnings group.

Figure 2.3 shows that higher-level technical students are more likely to be in higher earnings groups. While all classroom-based students at Level 2 and below are in the bottom 2 earnings groups, 9% of students taking classroom-based courses at Level 3 and above are in the top 2 earnings groups. Furthermore, while only 17% of apprentices at Level 2 and below are in the top 2 earnings groups, 43% of apprentices at Level 3 and above are in the highest earnings group.

Figure 2.3: Learners taking technical post-16 courses in each earnings group

| Earnings group | Level 2 and below classroom | Level 3 and above classroom | Level 2 and below apprentice | Level 3 and above apprentice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | - | - | - | 43% |

| Middle upper | - | 8% | 17% | 3% |

| Middle lower | 33% | 38% | 36% | 27% |

| Low | 67% | 53% | 47% | 27% |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. All cell sizes are greater than 1,000.

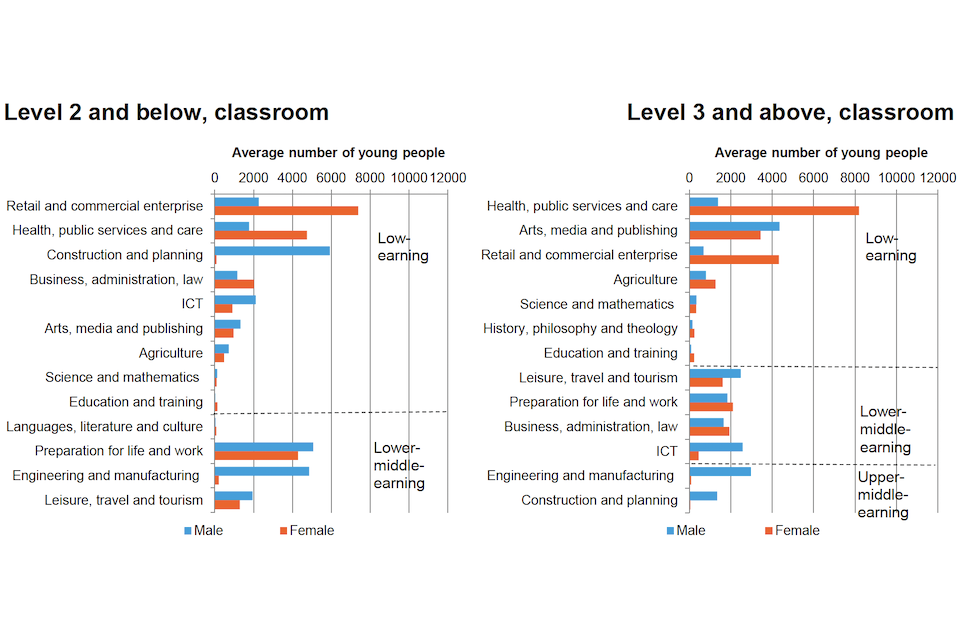

There are also significant gender differences in the numbers of students taking different technical courses, with men far more likely to take technical courses associated with high earnings. This is demonstrated in Figures 2.4 and 2.5, which provide a breakdown of the number of men and women studying technical courses by subject area.

Figure 2.4 tells us that women tend to take low-earnings classroom-based courses in subject areas such as retail and commercial enterprise, health, public services and care. Men take the few classroom-based technical courses that are relatively high-earning, such as engineering and manufacturing; and construction and planning (at Level 3 and above).

Figure 2.5 demonstrates that women are also much more likely to undertake low-earning apprenticeships in subject areas such as retail and commercial enterprise, as well as health, public services and care. The high-earnings apprenticeships – especially in engineering and manufacturing – are overwhelmingly taken by men.

This chimes with other recent evidence showing that girls are much less likely to take post-16 courses in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects.[footnote 10]

Figure 2.4: Classroom-based learners studying each subject area by gender

Figure 2.5: Apprentice learners studying each subject area by gender

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. All cell sizes are greater than 50, with figures showing the average number of students across years. Three subject groupings were removed from Figure 2.5 due to low sample sizes, to prevent secondary disclosure.

3. Socio-economic differences in course choices

In this section, we look at which post-16 choices are socially graded and the role they may play in shaping social mobility. We use an index of socio-economic background, which combines individual eligibility for free school meals and area-level characteristics (see box below).

Key findings

The most privileged men are 28 percentage points more likely to take a course in the top 25% of earnings than men in the most deprived group; the socio-economic gap is 31 percentage points for women.

Students with ‘just above average’ levels of deprivation are 20–25 percentage points less likely to take a course in the top 25% of earnings.

About 50% of disadvantaged women take low-earning courses in the bottom 25% of earnings, which compares with about 31% of men from similarly disadvantaged backgrounds.

Among those taking technical qualifications, women are 10 percentage points more likely to take courses in the lowest earnings group.

While prior attainment is the most likely predictor for taking higher-earning courses, some specific groups are less likely to take them, even if they are high achieving:

- disadvantaged students, with high levels of prior attainment, are less likely to take higher-earning academic routes

- disadvantaged women, with low/middle levels of prior attainment, are more likely to take low-earning technical courses

Disadvantage has persistent effects on early-career earnings, even after controlling for detailed measures of prior attainment. Very little of these inequalities can be explained by subject or course choices for men. However, about 4 to 5 percentage points of the earnings penalty for disadvantaged women reflects their post-16 subject and course choices.

Only 27% of women and 22% of men from disadvantaged Black Caribbean backgrounds took higher-earning courses in the top 50% of earnings.

Disadvantaged White British women are much less likely to take higher-earning courses than men from the same background (24% vs 33%).

Disadvantaged women in London are over 10 percentage points more likely to take high- earning courses than disadvantaged women in all other regions of England. Disadvantaged women in the north-east and north-west are the least likely to take high-earning courses. The same patterns hold for men, but the differences are much less pronounced.

These regional disparities are likely to be linked to the differing availability of courses and institutions, with school sixth forms much more common in London.

Measuring socio-economic status

A central component of our analysis is investigating socio-economic differences in education and earnings, which requires us to have a measure of socio-economic status. We have calculated a measure of each individual’s socio-economic background during their time in secondary school using information on a range of individual- and local-area-level measures of deprivation:

- eligibility for free school meals during their time at school

- the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI)[footnote 11] score in the local area

- local measures of housing tenure – the share of people that own their homes

- local measures of adult education levels – the share of adults with no qualifications

- the occupational share of adults in the local area

We have performed a principal-components analysis using information on these variables, which produces a socio-economic score for each person. In later analysis we assign individuals into 5 groups from the most-deprived quintile to the least-deprived quintile based on their socio-economic score. We are unable to calculate socio-economic scores for individuals who attended an independent school; instead we include independent school students in our analysis as a separate socio-economic group. This group attending independent schools is likely to be more advantaged and privileged than the most-advantaged quintile attending state-funded schools.

Overall socio-economic differences

Men and women from advantaged socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to take high- earning courses than those from disadvantaged backgrounds. About 38% of men and women from the most advantaged backgrounds (quintile 1) took high-earning (top 25%) courses. This compares with 10% of men from the most disadvantaged backgrounds (quintile 5) and just 7% of disadvantaged women. This creates a socio-economic gap of 28 percentage points for men in the likelihood of taking a high-earning course, and an even larger gap of 31 percentage points for women.

It is also clear that socio-economic differences extend well beyond the most disadvantaged group. For example, men and women in the most advantaged group are still more than twice as likely to take high-earning courses than the second most disadvantaged group, those with just above average levels of deprivation.

If we look at the top 50% earning courses (high and upper-middle combined), there is a socio- economic gap of 47 percentage points for women and a 37 percentage points gap for men.

The gender and socio-economic divides become even starker if we look at the share of men and women taking low-earning courses (bottom 25%). Women are much more likely to take low-earning courses than men if they’re from disadvantaged backgrounds (50% vs 31%). There is also a gradual effect of socio-economic background. Men and women from average socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to take low-earning courses than those from the most advantaged group, as are those with below-average socio-economic background scores.

In contrast, men and women from independent schools are much more likely to take high- earning courses. About two-thirds of men and women from independent schools take high- earning courses, which is about 30 percentage points greater than the proportion of men and women from the most advantaged backgrounds in state-funded schools (quintile 1). This results from a greater focus on A levels and other academic qualifications in independent schools.

Figure 3.1: Percentage of learners taking post-16 courses in each earnings group by socio-economic status (private school + quintiles)

Men:

| Earnings group | Private school | Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 68% | 38% | 29% | 23% | 17% | 10% |

| Middle upper | 20% | 28% | 26% | 25% | 22% | 19% |

| Middle lower | 9% | 23% | 30% | 34% | 38% | 40% |

| Low | 4% | 10% | 14% | 18% | 24% | 31% |

Women:

| Earnings group | Private school | Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 67% | 39% | 28% | 21% | 14% | 7% |

| Middle upper | 22% | 29% | 27% | 24% | 20% | 15% |

| Middle lower | 6% | 16% | 21% | 25% | 27% | 27% |

| Low | 5% | 16% | 24% | 31% | 39% | 50% |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. All cell sizes are greater than 1,000.

Socio-economic differences within technical routes

Figure 3.2 shows the share of men and women taking technical qualifications in the different earnings groups by socio-economic background. A much greater share of technical courses are in lower earnings groups: over 80% of learners on technical routes are taking low- or middle-to low-earning courses.

There are, however, still socio-economic and gender differences. About 58% of the most disadvantaged men (quintile 5) taking technical courses are on low-earning courses – that’s about 13 percentage points more than the most advantaged men doing so. Among women, 67% of the most disadvantaged women on technical routes are taking low-earning courses, which is 9 percentage points more than among women in quintile 1. There is also a gradual effect of socio- economic disadvantage increasing the likelihood of taking low-earning technical courses. Across all groups, women on technical routes are about 10 percentage points more likely to take low-earning courses than men (see Figure 3.2).

Higher-earning technical courses tend to be Level 3 classroom courses and apprenticeships, particularly those in the areas of construction and engineering. Given that these areas are male- dominated, it is not surprising to see such larger gender divides. Women are much more likely to take technical courses in care, public service and retail, which tend to be low-earning.

Figure 3.2: Percentage of learners taking technical post-16 courses in each earnings group by socio-economic status (private school + quintiles)

Men:

| Earnings group | Private school | Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 4% | 9% | 9% | 8% | 6% | 4% |

| Middle upper | 6% | 7% | 8% | 8% | 7% | 7% |

| Middle lower | 41% | 39% | 37% | 36% | 34% | 32% |

| Low | 49% | 45% | 46% | 48% | 52% | 58% |

Women:

| Earnings group | Private school | Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Middle upper | 3% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| Middle lower | 41% | 38% | 36% | 35% | 33% | 30% |

| Low | 55% | 58% | 60% | 61% | 64% | 67% |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. All cell sizes are greater than 50.

Differences for more recent cohorts

The main analysis focuses on individuals who took their GCSEs and made their post-16 choices during the mid-2000s, so that we can track their earnings up to the age of 30. As a check on the relevance of this, we also looked at a more recent cohort (students taking GCSEs between 2009 and 2012, versus 2002 to 2005 for our main cohort).

Generally speaking, the socio-economic differences in post-16 choices are extremely similar for both cohorts. This assumes that courses that are high- and low-earning have remained similar over time.

Figure 3.3 shows that the share of men and women in each quintile taking higher-earning courses fell by about one to 3 percentage points in independent schools and across quintiles 1–4. There is a slight rise of one percentage point in quintile 5 (for women).

Appendix Figure A1 shows the full splits by each earnings group for the most recent cohorts.

Figure 3.3: Percentage of students taking post-16 courses in the top 50% of earnings groups by socio-economic status (private school + quintiles)

| Earnings group | Private school | Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (2002 to 2004) | 87% | 67% | 55% | 48% | 39% | 29% |

| Men (2009 to 2012) | 85% | 65% | 53% | 45% | 37% | 29% |

| Women (2002 to 2004) | 88% | 68% | 55% | 45% | 34% | 22% |

| Women (2009 to 2012) | 86% | 66% | 52% | 43% | 33% | 23% |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005, and from 2009 to 2012. All cell sizes are greater than 1,000.

Explanations for socio-economic differences

As Figure 3.3 shows, the likelihood of someone taking a post-16 course associated with high future earnings depends on which socio-economic group they are in. The higher the socio- economic group, the greater the chance of high earnings. This is partly because students from well-off backgrounds are more likely to choose A levels, which are more strongly linked with well paid careers. There is a huge disparity between groups and these differences are most pronounced for women.

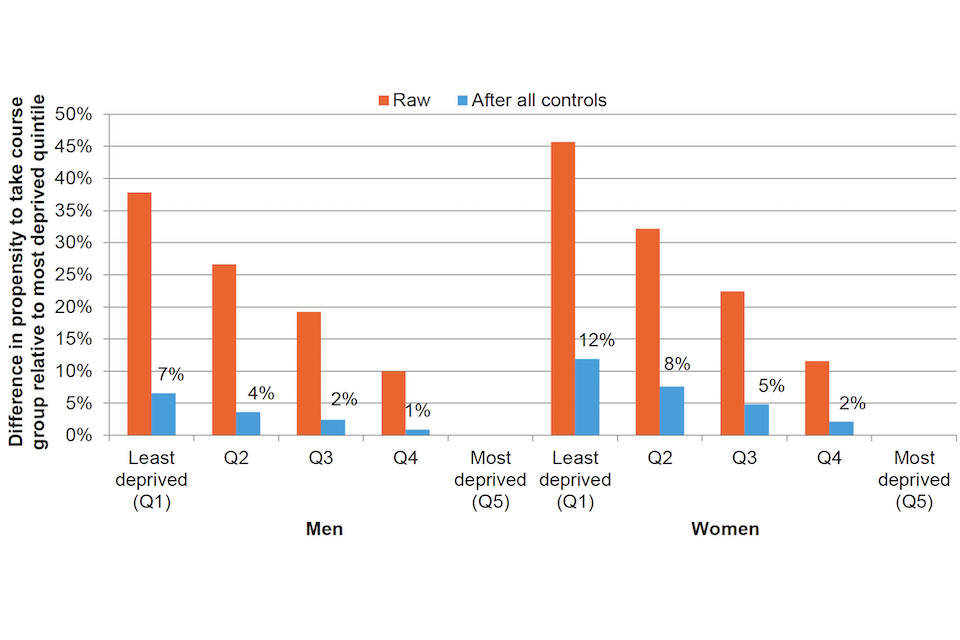

The effects are smaller, but still notable, among those taking technical qualifications. There is also a larger gender split, with women 10 percentage points more likely to take courses in the lowest earnings group.

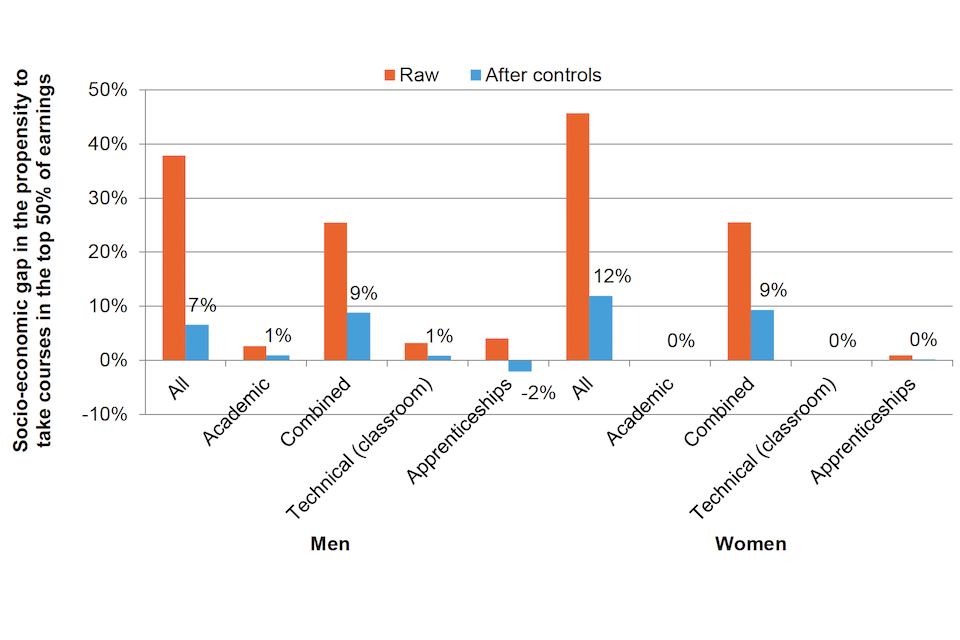

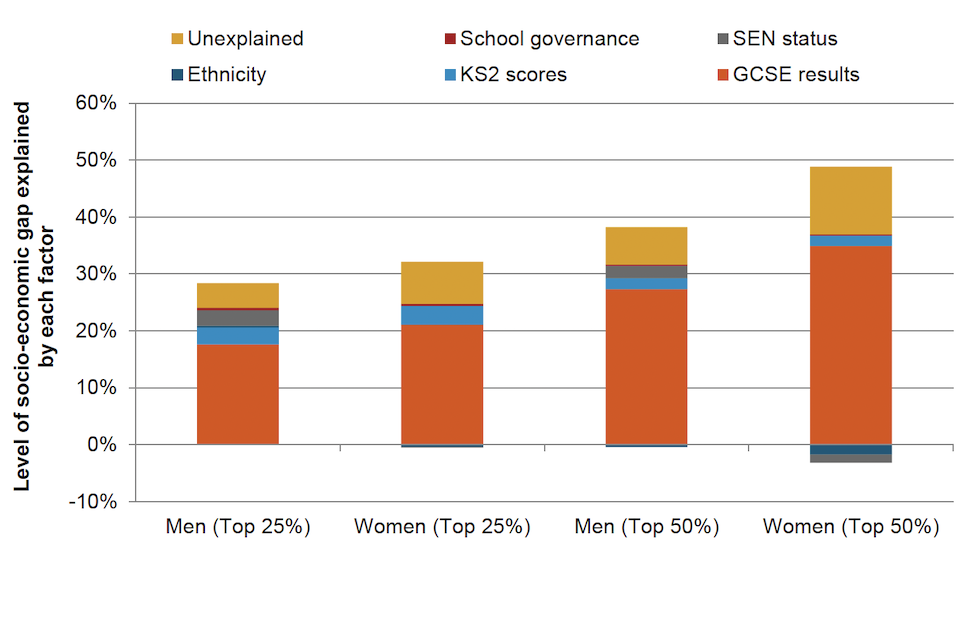

After controlling for prior attainment and pupil characteristics,[footnote 12] the likelihood of taking a course in the top 50% for earnings varies by 7 percentage points for men and 12 percentage points for women (comparing the most disadvantaged group with the most advantaged group). Similar results can be seen for the likelihood of taking courses in the top 25% for earnings (see Appendix Figure A2 for further details). In both cases, prior attainment can explain about 70% to 80% of the socio-economic gap (Appendix Figure A3).

Individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to take courses associated with lower earnings even after accounting for lower prior attainment. This is particularly the case for women. The chances of them choosing a course in the top 50% vary by 12 percentage points across quintiles (compared with a 7 percentage points for men).

Figure 3.4: Socio-economic differences in the propensity to take high-earning courses (top 50%) before and after controls

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005.

Figure 3.5 shows that an individual’s broad choice of route is most likely to determine the later financial outcome (academic or combined as opposed to technical or apprenticeship). There is a socio-economic gap of 8 to 9 percentage points with the combined route.

Figure 3.5: Socio-economic gap in the propensity to take post-16 courses in the top 50% of earnings (shown separately for men and women)

The socio-economic gap is defined as the difference in percentage points between the most and least deprived groups. The figures below are shown before and after controls.

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005.

The above analysis looks at men and women of all levels of prior attainment.

We have also examined differences within groups for students with similar levels of prior attainment. The men and women have been divided into 3 equally sized groups based on their GCSE results (high, middle and low prior attainment). We have then looked at the propensity to take academic and combined courses in the top 25% for earnings for the high- and middle-attainment groups (Figure 3.6), and at the propensity to take technical and apprenticeship courses in the top 75% for earnings for the low- and middle-attainment groups (Figure 3.7).

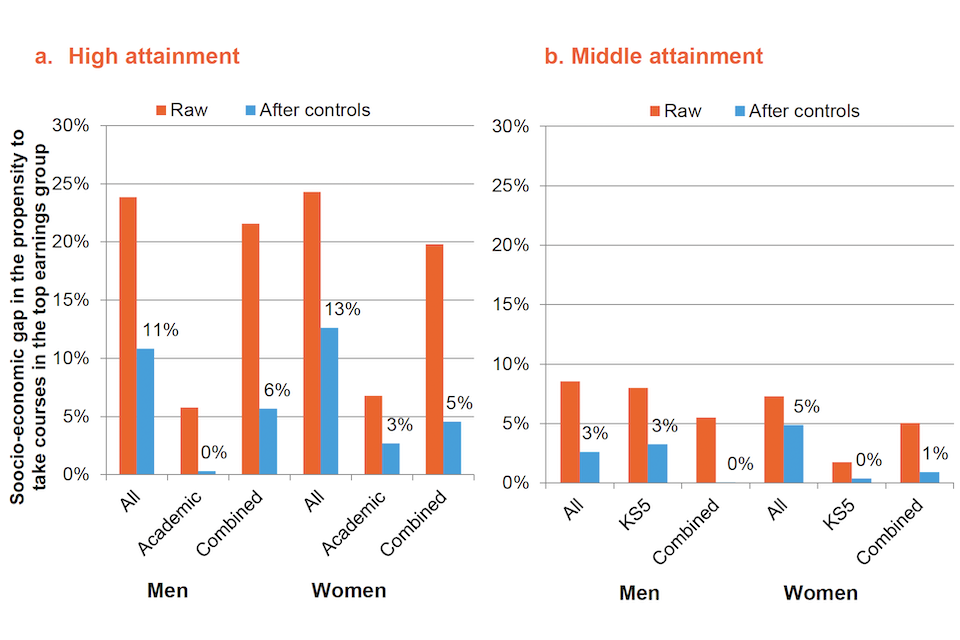

Disadvantaged men and women with high levels of prior attainment are less likely to take high- earning courses, and this is largely down to their choice of broad route – that is, their lower likelihood of taking an A level-focused route. As Figure 3.6 shows, there are significant socio-economic gaps of about 11 to 13 percentage points in the likelihood of taking a high-earning (top 25%) course between men and women with high levels of GCSE attainment, even after accounting for detailed measures of prior attainment and pupil characteristics. These gaps are generally much lower (less than 5 percentage points) within the academic and combined routes. They are also much smaller within the middle-attainment group.

Figure 3.6: The socio-economic gap in propensity to take post-16 courses in the top 25% of earnings

The socio-economic gap is defined as the difference in percentage points between the most and least deprived groups. The figures below are shown before and after controls.

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005.

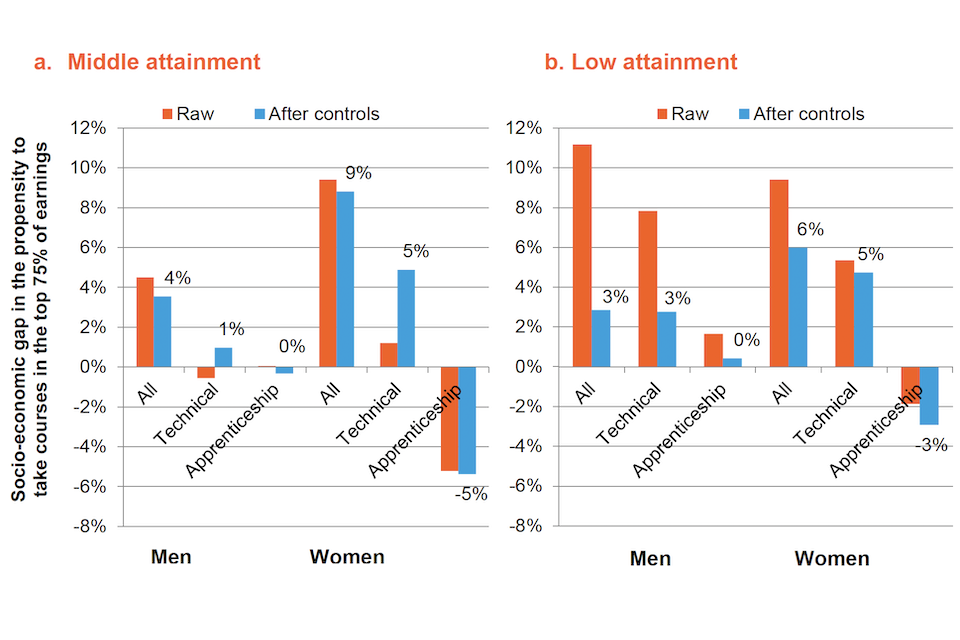

Figure 3.7 shows the socio-economic disparities in courses linked to the top 75% for earnings – you can see the overall figures and breakdowns within the technical and apprenticeship course routes. For men, there are relatively small socio-economic gaps after controlling for prior attainment (around 3 to 4 percentage points for the middle- and low-attainment groups).

For disadvantaged women, the socio-economic gaps are much larger, even after controlling for prior attainment. Overall, these women are 6 to 9 percentage points less likely to take a course in the top 75% for earnings. If they study classroom-based technical courses, they are 5 percentage points less likely to take a course in the top 75% for earnings. For instance, as we saw in section 2, they’re more likely to choose low-earning courses in retail, commerce, public services and care. Within the apprenticeship route, if they have low or middle attainment, they’re actually more likely to take courses in the top 75% for earnings – but it’s a very small group in practice.

Figure 3.7: The socio-economic gap in propensity to take post-16 courses in the top 75% of earnings

The socio-economic gap is defined as the difference in percentage points between the most and least deprived groups. The figures below are shown before and after controls.

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005.

Social mobility implications

We have estimated the relative role that course choices play in explaining the differences in early-career earnings for men and women. This is so that we can quantify the potential social mobility consequences.

We treat men in the least deprived quintile as our reference group and compare earnings with those of men and women from other socio-economic backgrounds. This allows us to examine the joint role played by socio-economic background and gender.[footnote 13] It is important to note that we are looking at earnings among those in employment, not wage rates per hour, and any differences could reflect differences in both the wages and hours worked.

As expected, men in the most deprived quintile earn substantially less than men in the least deprived quintile (30% less in raw terms). This reduces substantially to 6% after accounting for differences in prior attainment and pupil characteristics. Controlling for detailed course choices has little further effect. It therefore seems to be the case that differences in prior attainment explain the vast majority of the socio-economic differences in early-career earnings among men, though the outstanding 6% can’t be accounted for by prior attainment or subject/course choices.

Figure 3.8: Difference in earnings relative to the least deprived men at age 26, with and without controls

| Socio-economic status | Raw differences | Plus controls for pupil characteristics | Plus controls for detailed course route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most deprived males | Minus 30% | Minus 11% | Minus 47% |

| Least deprived females | Minus 6% | Minus 15% | Minus 33% |

| Most deprived females | Minus 6% | Minus 12% | Minus 28% |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, IPR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. Figures show the estimated percentage differences between each group and the least deprived quintile of men. Full details in Appendix Tables A4 and A5.

In raw terms, figure 3.8 shows that women in the least deprived group earn 11% less than men from similar backgrounds. This increases to 15% when we account for the higher levels of prior attainment. It’s down to 12% once we control for detailed course groups, such as level and subject.

The most deprived women earn substantially less than the least deprived men. Even after adding controls for lower levels of prior attainment, there’s a 33% difference. That reduces to 28% once we control for detailed course choices by level and subject.

The effects of socio-economic background are also much more impactful for women than they are for men. Addressing these barriers early on could have significant impacts on their future earning potential and close the gender pay gap.

Among the least deprived group, women earn about 12% less than men. Amongst the most deprived group, this increases to 22%.[footnote 14]

These effects aren’t influenced by employment rates, as our focus is on individuals who are earning money. They could, however, be partially driven by different choices on hours of work. Unfortunately, a lack of data on hours worked means that we cannot estimate the size of any such effect.

Conclusion

The evidence shows that prior attainment plays a dominant role in explaining socio-economic differences in earnings, particularly for men. However, even when attainment is accounted for, clear differences remain, with women from deprived backgrounds being the most negatively impacted. Detailed post-16 choices have minimal impact on men’s earnings. However for deprived women, the choice made could explain 4% of the 47% earnings gap with the least deprived group. That 4% may seem small but it could still result in notable social mobility consequences.

Ethnic and regional differences

There are strong differences in post-16 choices by ethnicity. Figure 3.9 shows the variations among ethnic groups for students in the 2 most disadvantaged quintiles taking courses in the top 50% for earnings (also Appendix Figure A4).

Disadvantaged men and women from Chinese and Indian backgrounds are the most likely to take higher-earning courses (over 50% take courses in the top 50% for earnings). In contrast, disadvantaged men and women from Black Caribbean backgrounds are among the least likely to take higher earnings courses (about 27% of the women and 22% of the men).

Differences were smaller among other ethnic groups, with about 35% to 40% of disadvantaged men and 40% to 50% of disadvantaged women taking higher-earning courses. There are, however, some notable gender differences. Over 50% of disadvantaged women from Black African backgrounds took higher-earnings courses, compared with 39% of the disadvantaged men. In almost all cases, disadvantaged women were more likely than men to take higher- earning courses. However, women from White British backgrounds were less likely (24%) to take higher-earning courses than men from White British backgrounds (33%). This has an impact on the overall figures.

Differences by region are much smaller than by socio-economic background or by ethnicity (full differences are shown in Appendix Figure A5). The share of disadvantaged women taking high- earning courses is highest in London and lowest in in the north-east and north-west. There are similar patterns for men, though the disparity is smaller. These regional patterns seem likely to be driven by differing socio-economic structures and potentially local availability. For example, London has the largest share of school sixth forms and ready access to high-earning academic qualifications, while the north-east and north-west of England have the lowest share of school sixth forms.[footnote 15]

Figure 3.9: Percentage of men and women in the most disadvantaged 40% taking post-16 courses in the top 50% of earnings, by ethnicity

| Ethnic group | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 64% | 73% |

| Indian | 52% | 62% |

| Black African | 39% | 53% |

| Bangladeshi | 38% | 48% |

| White Other | 37% | 39% |

| Pakistani | 36% | 43% |

| Other | 34% | 31% |

| White British | 33% | 24% |

| Black Caribbean | 22% | 27% |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. All cell sizes are greater than 50.

Figure 3.10: Percentage of men and women in the most disadvantaged 40% group taking post-16 courses in the top 50% of earnings by region

| Home region at age 16 | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Inner London | 36% | 42% |

| Outer London | 38% | 40% |

| East Midlands | 36% | 29% |

| East of England | 34% | 28% |

| West Midlands | 33% | 28% |

| South East | 33% | 27% |

| South West | 34% | 25% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 33% | 25% |

| North West | 33% | 25% |

| North East | 32% | 23% |

Notes and sources: Authors’ calculations using linked data from NPD, ILR and HMRC earnings data. Sample of young people taking GCSEs between 2002 and 2005. All cell sizes are greater than 1,000.

4. The drivers of post-16 education choices

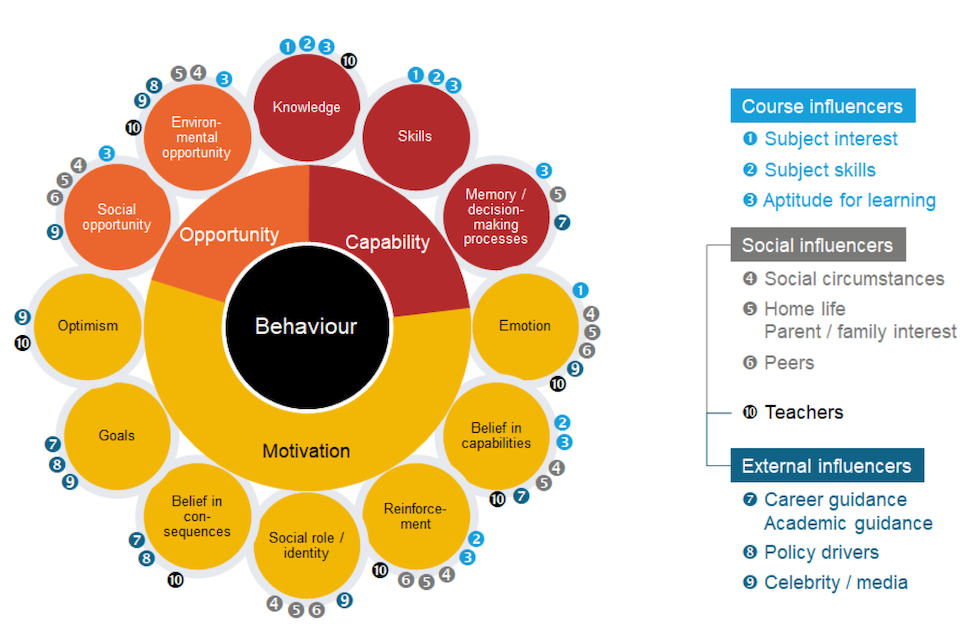

This chapter uses interviews with providers and learners to describe the wider behavioural drivers affecting course decisions (see the box below for a description of the overall approach).

Key findings

Young people taking higher-level courses are usually better informed about the education pathways and opportunities open to them compared with those taking lower-level courses.

Only 3 in 5 young people say they received careers guidance before the age of 16, suggesting a major gap in current provision. Lack of knowledge at age 16 about related education and career pathways can inhibit the learners’ course choice.

FE colleges and providers play an important role in shaping choices and go to significant lengths to improve knowledge, through outreach materials, taster sessions and an initially varied curriculum.

Higher-achieving learners are more likely than others to be able to access the course they enjoy and are often better able to articulate their career goals. The choices available to lower-achieving learners are limited by requirements to address gaps in their knowledge of core subjects critical to post-16 courses.

Gender roles remain a pervasive influence on learners’ course selections and there is a lack of role models on learners’ course choices.

Apprentices value the financial stability this route provides.

Public transport links and the cost of travel can influence learners’ choice of provider and courses, particularly for apprentices. If they are able to, providers should subsidise public transport costs for learners to increase access to their courses.

Behavioural approach:

We conducted in-depth interviews with senior leaders, teachers and learners from 5 learning providers – 4 general further education colleges (GFECs) and one independent training provider (ITP) – plus a senior leader from an additional ITP and one employer. The COVID-19 pandemic meant that only half of the anticipated interviews were completed. The findings have been analysed using the COM-B behavioural framework of Michie, Atkins and West (2014). Full details of the fieldwork approach can be found in Appendix B.

Capabilities

Prior skills and knowledge of progression routes are critical factors in learners’ course selection decisions. In this section, we discuss the role played by prior attainment, learners’ knowledge of how to navigate the system, and how providers seek to influence and inform choices.

Role of prior attainment

The quantitative analysis shows that prior attainment is the key determinant of learners’ course selection, influencing the level and type of course chosen, as well as the provider. Learners’ prior achievement in English and maths was considered by many staff, and learners, as critical to their course choice. Learners without at least a GCSE grade 4 in English and maths typically retake these exams in order to access Level 3 courses.[footnote 16] Government policy has also been targeting shortfalls in English and maths for some time and directed the FE sector to support learner attainment in these subjects.

Similarly, some learners said they chose a particular provider or lower-level technical course by default as a result of lower achievement. These learners said that their low GCSE English and maths grades meant they could not take academic subjects at sixth forms and so they became apprentices or directly entered Level 2 or 3 technical courses instead.

Knowledge of system, opportunities and pathways

Knowledge of available options, and the related education and career pathways, is an important factor in course choice. Learners’ prior attainment levels, access to careers advice, the quality or availability of advice from family contacts, and prior experience are perceived as key to the decision making. Many staff interviewed for the study, particularly in FE colleges, commented that some learners had not acquired the skills or knowledge to determine the suitability of courses based on their abilities, interests and careers aspirations.

Lower-level courses or courses applicable for a variety of occupations, such as ‘business’, are sometimes considered by the staff to attract learners who are uncertain about their education or career. Learners with lower achievement are more likely to be channelled towards these courses because they are accessible and keep learners’ options open. However the students are more likely to drop out or change course.

Learners on higher-level and more technical courses were viewed by some staff to be better informed about progression routes, often because they had a clearer idea of their future direction.

“Anyone below Level 2 has poor information with regard to their next steps and why they’re going on to a programme. With Level 3 and above, especially with science and engineering, they’re a little bit more informed about what they want, with almost a destination in mind.” (GFEC, senior manager)

Sources of information

Learners gain information and knowledge of the post-16 education system from a variety of sources: careers guidance at school before age 16; their own research and experience; and active efforts by providers.

Role of careers guidance at school:

Many staff believe that learners’ lack of knowledge stems from insufficient access to careers guidance prior to enrolling post-16. The survey evidence shows that only 61% of young people aged 13 or 14 report having received any careers advice (see accompanying literature review, Table 3). At age 14 or 15, a similar proportion (59%) received support from a careers adviser coming into their school. Similar levels of careers guidance were reported by students of all backgrounds.

Learners’ own research and experience:

Some learners undertook their own research about onward academic and career progression routes before selecting their first course post-16. For example, research by some learners identified that business and travel courses offered a breadth of career options. Other learners reviewed providers’ websites to identify and understand the courses offered, or attended providers’ open days and consulted prospectuses. As a result, they said they felt more informed about their options and this influenced their choices.

Other sources of knowledge noted by interviewees include prior experience in an industry or understanding gained through developing a skill relevant to a vocation, such as:

- previous employment or part-time jobs

- learners with a talent or hobby-based skill, such as IT or creative arts

Other research also notes the effect that wider media and celebrity can have in influencing educational choices.[footnote 17]

Active efforts by providers:

Providers undertake a wide range of activities to increase learners’ knowledge and hence improve course decision-making. For example:

-

providing promotional materials and hosting events to inform learners about available courses and associated career pathways – staff interviewees were particularly positive about the role played by alumni and employers.

- offering multiple taster sessions to improve prospective learners’ knowledge of course options and progression routes

- working with schools to inform learners and parents/guardians about potential courses and resulting career options[footnote 18]

- providing personal interactions in combination with promotional materials – some learners said they would not have considered taking up their courses without face-to-face contact and discussion with post-16 teachers

- offering pre-course interviews to potential learners – staff said that these help learners to choose courses that reflect their skills, interests and aspirations

- offering tasters of the lower-level courses with wide-ranging curriculums so that learners can explore the different subjects

“A lot of learners aren’t sure what they want to do, particularly at the lower levels, so it’s important to give them a broad exposure, to enable them to progress and specialise as they go. For example, at 16, at Level 2, you might not really know what ‘events management’ is. But if you get a taster of it, within your first year, you can then progress through the course.” (ITP, senior leader)

Case study: Stanmore College – supporting and advising learners to follow non-academic career routes

This is a relatively small general FE college in north west London with 3,000 learners aged 16+. It offers a broad range of non-trade-based vocational qualifications (business studies and engineering) from Levels 1 to 6. They offer all new students a taster day ‘so they get a good flavour of what they might enjoy.’

Senior leaders believe that a key strength is giving learners a second chance. A leader said: ‘It gives them a second opportunity to do better than they did at school where some had a pretty poor experience’. The staff describe how important it is to help nurture and develop learners.

The college takes a ‘rounded approach’ to education, helping students to identify their own interests and career paths. They would like young people to be informed about the vocational pathways available, ‘much much earlier’, so that they can make informed course choices post-16.

Summary of capabilities

Interviewees emphasised that young people taking higher-level courses are usually better informed about the education pathways and opportunities open to them compared with those taking lower-level courses. The latter are more likely to take generic courses. Providers also go to significant lengths to improve knowledge, through outreach materials and taster sessions.

Motivations

Our literature review shows that aspirations to continue in education or training are high, with 80% to 90% of young people wishing to continue in education. There is, however, a clear socio- economic gradient, as 94% of young people from professional backgrounds aspire to stay in education compared with 82% of those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

There are also large socio-economic differences in specific pathway aspirations. Just over three-quarters (77%) of young people from professional backgrounds express a desire to progress to a sixth form, compared with half (50%) of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. Young people from more disadvantaged backgrounds are much more likely to prefer a course at an FE college.

The qualitative evidence shows that a wide range of motivational factors influence learners’ course selections. Learners often articulated a reason for selecting their course based on their aspirations, likes and interests, emotive experiences, and career goals.

Interests and past emotive experiences

Using interests in decision-making:

Prior interest in and enjoyment of a subject were recognised by staff as important drivers for learners’ course choices. Learners also frequently articulated at interview how their course selection was driven by their love or enjoyment of a subject. This emotive reaction covered a range of courses, from automotive to travel and business, across all educational levels.

“I think the primary driver for a lot of learners is interest and passion in that subject area… for a lot of learners, within the creative sector, it’s something that they’ve got an existing interest in anyway and it’s the chance to take it to the next level.” (ITP, senior leader)

Several learners demonstrated a strong passion for subjects in which they had developed prior skills and experience through a hobby or talent – for example, gaming and coding in IT, or singing and dancing. In these cases, the capability and motivational aspects of behaviour are symbiotic: the learner’s interest leads them to develop skills which, in turn, feeds their interest.

For some provider staff, helping learners to identify subjects that relate to their areas of interest and enjoyment is considered an important way to guide course selection, and can improve subsequent retention on those courses.

The motivational impact of past experiences:

Past emotive experiences are also important drivers behind some learners’ course selection decisions. For example, according to staff at one FE college, courses in health and social care often attract learners who have personal experience of mental health issues or have observed family members experiencing the challenges of addiction.

Aspirations

Prior attainment influenced the way some learners articulated future aspirations. Learners who achieved the grades that enabled them to follow their preferred course held clearer, longer-term goals compared with the more limited choices available to those missing grades. Staff said that more technical courses which require high prior grades (such as engineering) are taken by learners with a clearer idea of future goals.

Conversely, learners who achieved lower grades than expected, and were unable to choose the course they had originally anticipated, appeared less certain about their future. These learners faced a knock in confidence, leading them to reconsider if and how they could achieve their goals.

“I had a small little goal in mind of what I had wanted to do… then my grades were actually worse than they should have been, for what I wanted, so I ended up getting put onto a BTEC route rather than what I had originally wanted.” (GFEC, Level 3 learner)

Staff also recognised that a learner’s belief about their capability plays an important role in their aspirations. Learners taking lower-level courses because of lower GCSE achievement are perceived by provider staff as less confident about their abilities and holding lower aspirations. A learner’s choices are limited by poor prior attainment, leading to an increase in mandatory, corrective courses. Some, or all of the choice, is taken away from the learner.

“I think that it’s most difficult to aspire to achieving higher [grades] for the students that have really failed at school… They’re coming in at Level 1, and having to do their functional skills, or their GCSE English and maths.” (GFEC, senior leader)

Evidence shows that young people from more deprived backgrounds, or with low attainment at age 16, are more likely to find themselves on non-academic routes, including technical courses.[footnote 19] This is regardless of their earlier (high) aspirations. The disappointment which results from taking an unfavoured route with mandatory elements can hinder informed decision-making after age 16, particularly given the gaps in career advice provision and perceived lack of knowledge of technical routes.

A number of providers offer support to address motivation affected by low attainment. Some providers support learners with aspirations towards higher education by demonstrating the alternative routes they can take to achieve their original goal. One provider works with the learner to help them identify alternative courses of interest. Another invests significant time in interviewing learners prior to enrolment to fully understand their aspirations.

Career goals

The extent to which learners can select courses based on their longer-term goals varies. Based on the interview evidence, apprentices often have the strongest vocational aspirations of learners taking non-academic options post-16.

“[Apprentices] are motivated, they do want to progress … I think a lot of them are motivated by the chance to get work experience… they want to start their career, they want to progress.” (Employer)

Anticipated employment opportunities were perceived by some learners and staff to motivate learners to choose specific courses. Some provider staff from ITPs and colleges believe that courses such as IT and accounting attract learners because of their association with ample employment opportunities and relatively high salaries. As a result, some providers purposefully include the likely employment and salary outcomes of courses in their promotional materials.

“We’re always really clear in making those links to the sector, so in really simple terms this course could lead to X,Y, or Z… That is quite prevalent in our promotional literature and in the discussions that we have with learners.” (ITP, senior leader)

Some learners’ course selections (construction and beauty within our interviews) were influenced by parents, family members or friends who work in these sectors. Some learners also saw skilled trades as an opportunity to earn a high income and run their own businesses.

External influences

External factors influence some learners’ course selection decisions. These include:

- apprenticeships, which are perceived to offer financial stability and an opportunity to gain work experience and earn money at the same time

- the learning environment - some provider staff felt that their environment is to be considered more attractive than sixth forms by many learners, particularly those who have had a negative experience of school

- a number of factors linked to disadvantage, which were cited by staff at one provider, including local unemployment levels, drug addiction and mental health issues

Summary of motivations

Disadvantaged learners are more likely to take a technical route, even if they initially aspired to an academic route. The depth and quality of careers guidance is variable, and learners often lack experience of non-academic routes before age 16. Such inexperience can inhibit informed decision-making. Providers play a key role in helping to guide young people to courses based on their interests and career goals. Interest and past experiences are often key drivers of aspirations and choices. However, learners can be influenced by views on expected earnings, financial stability and the learning environment.

Opportunities

The local availability of provision, social factors and structural features of the FE system also influence post-16 course selection.

Local availability of provision

The academic literature shows that geography and local availability/choice of provision strongly influence the options available to learners from disadvantaged backgrounds. Students in poorer areas are 14 percentage points more likely to choose an FE college over a sixth form college, even after allowing for academic achievement at GCSE.[footnote 20] Some of this is explained by a combination of regional variation in the number of sixth form places available, and the fact that regions with fewer sixth forms tend to have more limited choices of A level subjects. For example, London has a high share of school sixth forms, with much lower availability in the north-west and north-east. In areas with more school sixth forms, mid-level attainers are less likely to study in FE colleges and more likely to take Level 3 qualifications compared with the national average.[footnote 21] In contrast, they are less likely to take Level 3 qualifications in areas with fewer school sixth forms. This shows that the easy and clear option of school sixth forms can encourage middle attainers to take a Level 3 course.

“Some transportation systems [in rural areas] are city prices. So, if you’ve got someone on an apprenticeship and only earning £4 to £5 an hour for the first year, suddenly being hit with an £8 or £9 return fare on public transport can have quite an impact on that individual.” (GFEC, teacher)

The evidence from qualitative interviews shows that transport costs and limited subsidies result in many learners choosing courses from providers closest to home. Financial and temporal costs are felt keenly by learners in rural areas and those who are badly positioned within urban transport networks. Travel can also be challenging for apprentices split between a workplace and a learning provider. Staff at one rural college noted that some of their learners wish to learn close to home and so they look for degree-level progression routes at the local college rather than more distant higher education institutions.

Case study: Truro and Penwith College – meeting the challenges faced by rural learners

- A large FE college with 2 main sites: the city of Truro and the Penwith area.

- Has 5,000 16- to 19-year-olds split fairly equally across academic and vocational, technical or occupation education, as well as around 600 apprentices.

- Offers a range of qualifications from Level 1 to Level 6 in most subjects except for land-based specialisms.

Truro and Penwith College draws learners from across the largely rural country of Cornwall, which is characterised by limited public transport services and areas of socio-economic deprivation. The travel issue is reflected in the relatively long commute of one of its learners studying a Level 2 motor vehicle course: ‘I live in Falmouth but Falmouth School didn’t offer the diploma… The college is about 45 to 50 minutes on the bus.’ The travel distance can act as an environmental barrier for disadvantaged learners.

The college provides bus bursaries to help learners from lower income families access its courses. One member of the senior management said: ‘We subsidise bus travel and there’s a bursary system depending on salary. So if you’re on a low income, you can get a bus pass for something like £30 or £50 for the whole year and that will get you to and from the college from anywhere in Cornwall.’ In addition, the college has recently opened its third campus at the Callywith site in Bodmin to serve learners in the more rural east of the county and reduce their need to invest as much time and money in commuting. ‘It’s 30 miles to the east of here because some learners were travelling 2 hours each way to get to us’ (senior leader).

Examples of actions taken by providers

Staff at a number of providers attempt to overcome cost barriers in a variety of ways:

- offering transport bursaries or subsidised bus passes

- working with employers to increase understanding of how costs affect learners’ course choices – this has resulted in some employers increasing their salaries for apprentices or supporting learners with public transport costs

- offering a range of high-quality courses to attract learners in rural areas

Staff at one provider said that travel barriers were less concerning for learners who had a clear idea about career pathways, had prior attainment or were taking courses at Level 3 or above. In short, they had stronger course-related incentives to travel.

For some, a provider further away from home can be attractive. Senior leaders and teachers cited the threat of gangs as one such push factor.

“We’ve had students chased down the road with people wielding knives, we’ve had acid attacks… this almost becomes their safe space.” (GFEC, senior leader)

Social influences

Gender roles remain a strong social influence on course selections, as do the actions and choices of peers. Parents also play a role. Where school staff offer guidance, they academic over technical routes for higher achievers, especially if the school operates a sixth form.

Gender roles:

A number of teachers said that traditional gender roles influence course selection. Men are much more likely to take technical courses such as engineering and IT, automotive or construction; women are more likely to take caring courses such as childcare or social care, and hair and beauty. Note the use of ‘obviously’ in the quote below, which suggests that long- standing norms run down the course choice pathway.

“Obviously, hair and beauty is very female-orientated. It’s very similar in automotive and construction [which are very male-dominated]… we work quite hard to inspire more females to go into automotive and construction [and vice versa] with hair and beauty.” (GFEC, senior leader)

Provider staff think the gender disparities in course choice replicate the gender bias in the respective industries. Senior leaders at one FE college also suggested that gendered choices are particularly common among learners with negative learning experiences at school, and those studying courses with fewer qualification prerequisites (construction for males and hairdressing for females).

Case study: Highbury College – gender stereotypes influencing course selection

- A medium-sized general FE college serving Portsmouth and surrounding areas of east Hampshire.

- Provides a range of academic and vocational courses across 6 centres, from pre-entry level through to foundation degrees.