UK vision for the EU’s digital economy

Published 20 January 2015

Europe’s electronic communications landscape has transformed into a digital world. A world dominated by internet platforms, constantly altered by new and at times disruptive technologies, and full of opportunities for start-ups that pay no heed to geographical boundaries when creating new products and services.

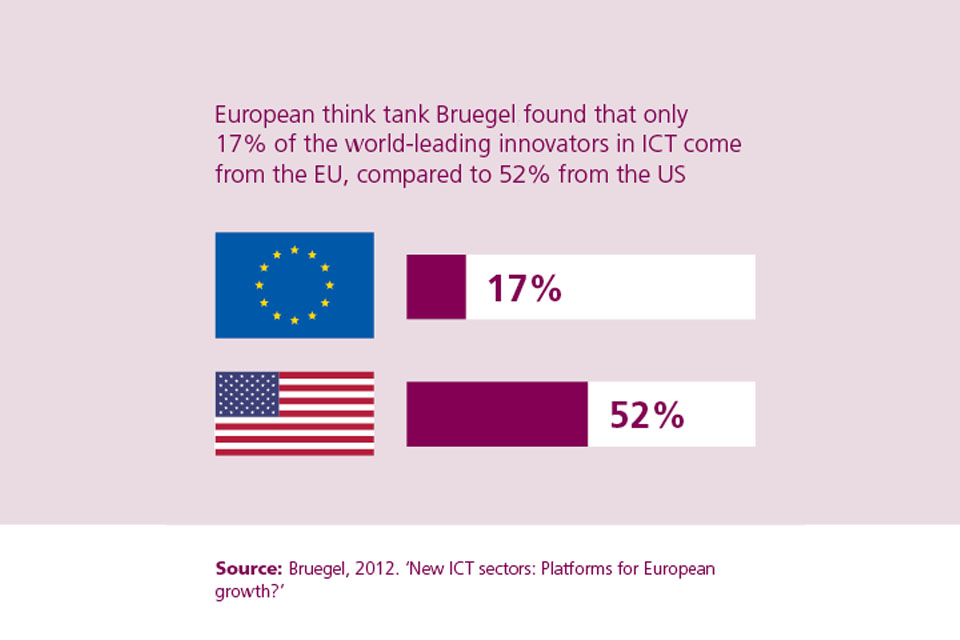

Europe starts from a great position – Estonia’s public service reforms, Germany’s start-up scene or the UK’s ‘fintech’ ecosystem are examples of real progress. Many European countries, such as Ireland, Belgium, and Sweden have high broadband speeds - with the Netherlands’ faster than the US average. But the continent’s patchwork of national markets and outdated legislation looks increasingly anachronistic in this new world. Compared especially to the United States, it is still too hard to start, fund and scale-up a digital business so that it can compete globally.[footnote 1]

Problems fall into a number of categories:

- Consumers are disadvantaged: customers of streaming services providing films, music or TV programmes should be able to access the services they have paid for when travelling in the EU – they currently cannot. And, similarly, customers shopping online just over the border should be able to take advantage of the buy-one-get-one free or 50% off offers that they would have accessed if they had driven to the shop in person.

- Start-ups don’t have easy access to a large market to work and trade in and so are disadvantaged compared to non-European firms. For example, new startups offering digital products and services across Europe currently have to meet the administrative requirements necessary to pay VAT in every country they sell to – rules designed for much larger businesses – and if they want to set up a web domain name in some Member States they have to have a physical address there.

- Innovation is being stifled in many parts of Europe. New exciting digital business models such as peer-to-peer services and ‘sharing economy’ businesses are restricted by regulations being introduced in some Member States. For a number of pan-European companies, this will diminish their potential market share compared to larger non-European Competitors.

- Public services across Europe are in many cases not yet digital by default, with some Member States offering a range of digital services, and others very few, and European citizens are not always clear about their rights online nor how their data will be used by different companies and governments, which stops them from shopping across borders. The UK proposes that the EU take bold steps to create an open, flexible market with a regulatory framework that reflects the dynamic nature of the digital economy. We must avoid knee-jerk reactions to the risks that accompany change, managing these by establishing a clear, simple set of rules that safeguard the rights of all those legitimately taking advantage of the online economy. We must also ensure that in an interdependent world, where supply chains are not just global but virtual and where trade negotiations now cover services and regulation, we use trade agreements to build a global digital economy.

This non-paper looks at the digital single market from two points of view: that of consumers, and that of entrepreneurs trying to break into the market. The market still doesn’t work for either of these groups in the way it does for the global players. We should not flinch from disrupting the status quo: in this phase of digitisation, even the giants of today – not long ago start-ups themselves – need to be open to challenge.

Our vision for the digital single market is one which is digital by default, where it is even easier to operate online across Europe than it is to do things offline in a single state. Where online businesses go through administrative processes once, not 28 times, and where football fans can stream matches they’ve already paid for wherever they go.

Below we set out what we think the EU should deliver over the next five years to achieve this vision.

1. Mobility and security – a Europe for digital consumers

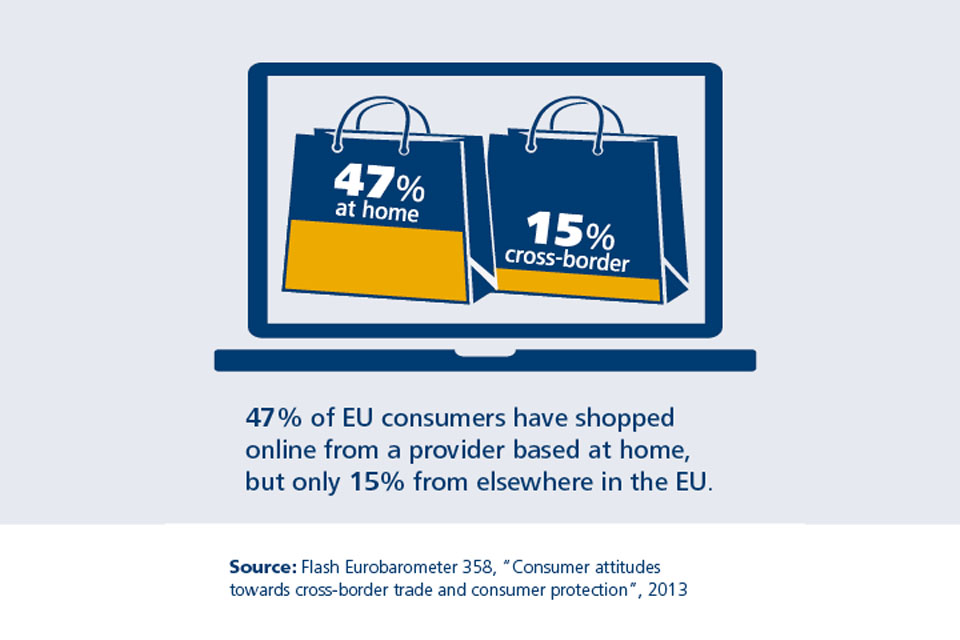

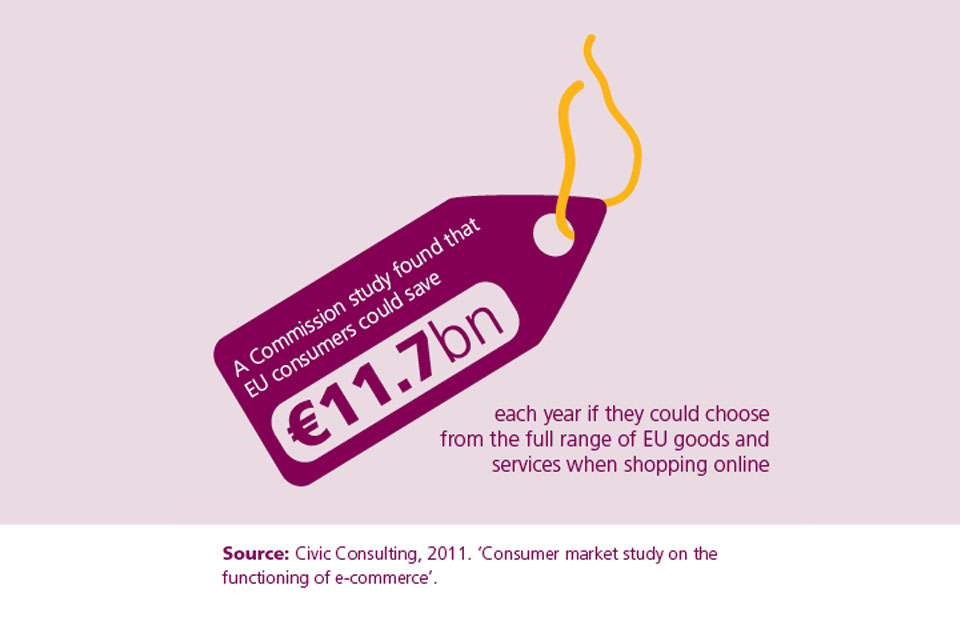

Having the internet in your pocket means you feel you should be able to shop anywhere, at any time, and buy from the widest range of providers. Consumers should not be penalised for using digital services or buying goods outside their home Member State, and they should be given confidence that their rights will be protected and their data used in a responsible and transparent way, on the basis of informed consent.

1.1 Consumers should be able to buy a wide range of digital products and services and use them wherever they are in the EU, just as they can with physical products

Their online subscriptions to music or film should still be available when they travel and they should be able to buy online content not easily accessible from a home provider: Europe’s creative output is one of its richest resources, and those who want to enjoy it should be able to pay to do so, even when it is only sold in another Member State. At the same time, Europe needs to maintain choice and diversity by protecting intellectual property in a way that ensures a flourishing and innovative creative sector. Our enforcement of the intellectual property regime must have teeth.

The Commission should ensure that consumers can access lawfully-available content on fair and reasonable terms across borders.

1.2 Prices for digital products and services should not change unfairly on the basis of where consumers come from in the EU [footnote 2]

When businesses raise their prices unfairly on the basis of the nationality of a consumer, their Internet Protocol or physical address, consumers suffer – and trust in the market decreases. Prices of course can differ legitimately, for example because of sales tax or delivery costs, but there should be no extra charges for making a payment simply because an online retailer is in one Member State and your card issuer in another, and national rules on promotions should not be allowed to stop consumers from one country taking advantage of an online offer that others can access. Consumers assume that they will not be discriminated against online on the basis of the country they live in. There ought to be transparency about pricing and businesses shouldn’t unfairly exploit consumers’ trust in the single market.

The Commission should review the extent to which consumers are discriminated against online on the basis of the country they live in and the economic and consumer consequences of this; and propose the necessary steps to address any unfair discrimination.

1.3 There should be a clear set of online consumer rights that are 100% enforceable by consumers.

It can be daunting enough to buy cross-border without worrying that your parcel won’t be delivered quickly or that a rogue business will mean it’s impossible to get help if there’s a problem. The EU needs a common set of consumer rights tailored to the purchase of digital content. These – and Europe’s other consumer protections – need to be easy for consumers to understand and act on, and properly enforced by all Member States working together. Some businesses are simply unaware of their obligations, so they need be better informed of how they should be protecting consumers. The EU must also find creative ways of making it easier for businesses to meet their obligations, as it can be difficult to understand the legal requirements of a consumer’s home market.

The Commission should review the implementation and enforcement of consumer rights, set out how consumer rights apply to digital products, and ensure that consumers and businesses understand their rights and have confidence that they will be enforced.

1.4 Consumers must be able to exert better control over their data and should be aware of how it will be used by businesses

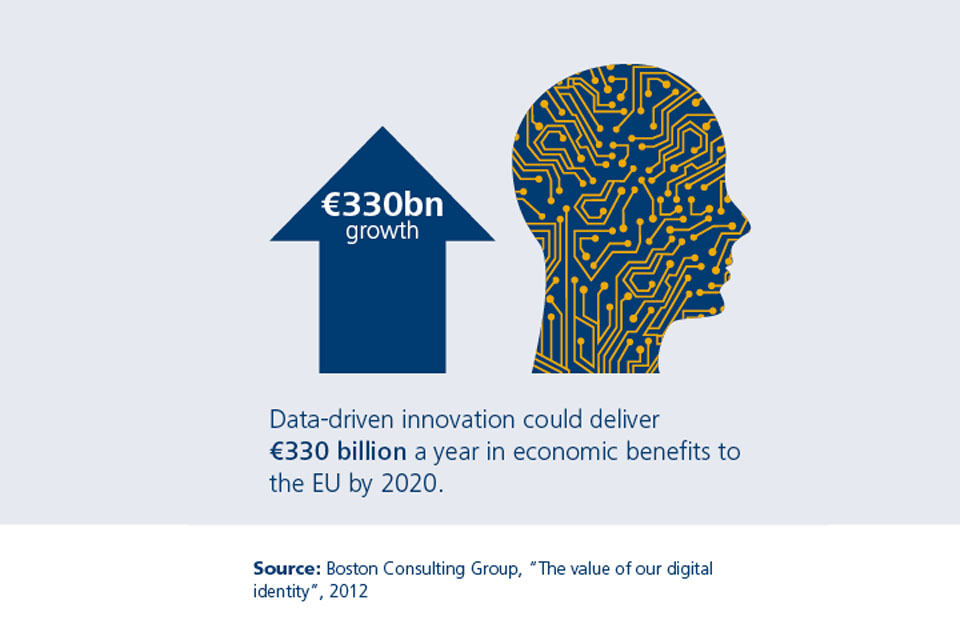

Data is the lifeblood of the digital economy. We all benefit from greater insight into consumer behaviour, which drives innovation. But consumers need a data protection framework they can trust if they are to be willing for their data to be used to unlock new and better services. We need to be prepared for the next evolution in the digital economy, which will be driven by consumers making choices about how to use their own data. So people must be able to obtain the data collected on them by service providers, so they can move it from one provider to another, or use it themselves. Of course new technologies also bring new risks and we need to set data protection in a broader framework that ensures the security of citizens. But the proliferation of data is inevitable and if we don’t create the right climate for seizing the opportunities this brings, we can be confident that data-driven innovation will continue elsewhere and simply be sold into the EU.

The data protection framework should be agreed as soon as possible, but it must be in a form that doesn’t suppress growth, supports data-driven innovation, and guarantees the protection of consumers’ data.

1.5 It must be possible to get online whilst in other European countries on the same terms as at home

In a mobile world, being charged a fortune to receive emails or use apps when there’s supposed to be a single market feels unfair. SMEs also need to be free to do business on the move. But the end of roaming charges must not create a disproportionately difficult environment for the challenger operators that are keeping home prices low, so the freedom for consumers to use their devices anywhere must go hand in hand with the freedom for operators to operate anywhere. That means infrastructure access for operators at a reasonable price via a reduction in wholesale costs.

The end of mobile roaming charges must be agreed during the current telecoms negotiations, with the viability of smaller operators protected.

1.6 Public services should be available to use online, saving people time, money, and the frustration of paper-based processes

Online processes can make it easier for users to see how their requests are being dealt with at the click of a button. By digitising services and requiring consumers to submit data less frequently, public services could also be provided more efficiently and more securely for everyone. The development of services which allow consumers to prove they are who they say they are when they access public services online, whilst safeguarding their privacy and civil liberties, should be supported. Where barriers prevent this also being available in the private sector, they should be tackled. These tools have the potential to give consumers access to banking, transport and other services online, without having to go through paper-based identification processes.

Member States should provide access to at least their 10 most-used public services online and reduce legislative barriers to all public and private sector services being accessed online across borders.

2. Innovation through competition – an economy for digital entrepreneurs

The internet offers innovators unlimited ways of offering better products and services, as long as we don’t have regulation that is easy to comply with for the big incumbents but a struggle for all other businesses. We have to design rules that help new entrants by providing a level playing field, not an obstacle course that defeats many would-be online exporters at the first hurdle. The Commission’s new investment plan highlights the need to remove barriers to service provision across the EU – this approach should apply equally to the digital market.

2.1 Online businesses should register once to operate everywhere in the EU

That’s how the digital single market should work. There should be a single process, valid across the EU, for:

- Registering a website domain name, with no requirement for a physical address in the country providing the name.

- Enabling companies to be formed within 24 hours, with all company law requirements able to be fulfilled electronically.

- Registering to pay VAT on all e-commerce within the EU.

- Navigating national identity requirements through a secure, business-friendly, cross-border electronic identity process.

- Finding information on how to trade online in any Member State.

The Commission should bring forward a package of legislative and non-legislative measures to deliver these outcomes for business.

2.2 New entrants with new ideas must not be frozen out of established markets

The importance of data has changed the dynamic of the online economy. The EU needs to look again at whether the competition framework remains fit for purpose, but we need an accurate understanding of online markets before jumping to conclusions. The European competition regime has a history of robust enforcement which breaks down incumbent power where there is abuse, and we need to continue to deliver these benefits in the context of a data-driven economy.

If, and only if, the economic evidence shows that there are unacceptable distortions of the market, then the Commission should of course consider all the remedies available to it to stop abuse. And as digital markets change rapidly, it should conclude cases much more quickly.

An open internet is absolutely essential to ensure the emergence of new and innovative business models. It’s therefore vital to prevent operators from blocking or throttling rival services, but in safeguarding net neutrality we must not be too prescriptive. By creating conditions which support challenger businesses, Europe will be doing the single most important thing to help launch winning European ideas into global markets.

The Commission should carry out an assessment of competition in online services markets. This should form the basis of an analysis of whether the competition framework meets the needs of the data-driven economy.

2.3 Online businesses should pay the right amount of tax

Within Europe, tax rules should be applied consistently to all companies, and digital businesses should pay the appropriate rate of tax on their profits in the countries where they generate those profits. Member States and the Commission should work together to ensure that internationally agreed rules can be introduced into the EU once they are finalised, as this will be the most effective means of tackling tax avoidance.

The OECD will consider specific solutions to address digital business models by the end of 2015 if recommendations on other base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) Action Points such as transfer pricing and permanent establishment do not go far enough. Member States should consider specific proposals upon conclusion and assessment of the OECD work.

2.4 The European tax regime should encourage entrepreneurship

The process for collecting VAT has to work for small and micro businesses operating across borders, otherwise many will be discouraged from selling outside their home Member State. The changes to VAT rules due to take effect from 1 January 2015 will ensure that large corporates pay tax fairly. But they were agreed before the rise of small, agile online businesses, some of which may face disproportionate difficulties in meeting these requirements. So, in addition to a single point for VAT registration and guidance, consideration should be given to a single cross-border VAT threshold below which businesses should not have to pay VAT or file a VAT return. Once a micro-business is big enough to reach this threshold, the Mini One Stop Shop service should relieve the burden where they operate across borders.

The Commission should consult business on the impact of the changes to VAT collection and propose reforms which lift the burden on small businesses.

2.5 The way that Europe legislates must meet the requirements of the digital economy

The internet allows start-ups to gain millions of new customers in a matter of months. This phase can make or break their business. If we want European companies to compete globally, we need to support them whilst they’re growing. While innovative businesses are scaling up, the EU should take steps to lighten the load from some of the excess regulation designed for bigger players.

All new legislative proposals should be innovation friendly and subject to a digital stress test as part of their impact assessment. And the existing body of law needs to be reviewed to ensure it’s still fit for the digital age.

The forthcoming review of the inter-institutional agreement on better lawmaking should consider the scope for reforming the legislative process to ensure that regulation meets the requirements of the digital economy. The REFIT process should determine which parts of the acquis should be reformed.

2.6 New technologies need to be interoperable and transferable across borders, so they develop in a continent-wide market[footnote 4]

Cloud computing, data science, manufacturing breakthroughs like 3D printing and the ‘internet of things’ will be enormous sources of growth, under the right conditions. The EU needs to help European firms to be early adopters of these technologies. It should ensure that Europe is in the lead in establishing or exploiting common definitions for off-the-shelf products and services, simple contracts that can be used cross-border by both businesses and consumers, and technical standards that allow interoperability where it’s needed, while retaining the flexibility necessary for continual innovation. This will stimulate the development of European players in new global markets. In telecoms markets, operators should be able to purchase standardised infrastructure access across the EU at a reasonable price. This will enable them to provide competitive telecommunications services to businesses operating across borders.

The Commission should work with the European standards bodies to promote, with industry and other ICT standards organisations, coherent digital standards that avoid market fragmentation. It should also ensure that national regulatory authorities define a single set of wholesale access products.

2.7 Data fuels creativity and innovation – we must make sure that anonymised data is available to be used

Researchers and entrepreneurs can put open data to work, and the bigger the data sets, the better the results. Member States and the Commission should support data-driven creativity by adopting the Open Data Charter and revise existing legislation to guarantee common standards for the publication of government data. This would mean that public sector open data from across Europe would be available for everyone to use and reuse – social problems would be better understood and public services would be improved.

Likewise, the EU should support copyright exceptions to allow research, education and text and data mining to take place across the market, and reject copyright levies in all forms, providing a major boost to European innovation. A Council Recommendation should propose the faithful adoption by all Member States of the Open Data Charter and the Commission should support easier data sharing within and between public service deliverers, underpinned by robust safeguards.

3. Continue the conversation

- Read the European Parliament’s assessment of the Cost of Non Europe - including estimates for savings from the digital single market

- Read the latest from the European Commission on its digital agenda

- Join the conversation on Twitter at #digitalagenda

4. Useful links and resources

- Making the single market more effective from the UK’s Department for Business, Innovation and Skills

- Reforming the single market

- The UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office

- The UK’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport

- The UK Intellectual Property Office

-

The economic benefits of completing the Digital Single Market are well recognised. The European Commission refers to €250 billion of potential additional growth over the course of the mandate of the new Commission. The European Parliament in its “Costs of Non-Europe – Digital Single Market” report on the Digital Single Market estimates the “gaps” they identify in the areas of cloud computing, payments, and postal and parcel delivery alone, correspond to €36 billion to €75 billion per annum. Work by Copenhagen Economics in 2010 (“The Economic Impact of a European Digital Single Market”) estimated that the EU could gain 4% of GDP by stimulating fast development of the Digital Single Market by 2020. ↩

-

A report undertaken by Matrix Insight for the European Commission in 2009 (“Study on business practices applying different condition of access based on the nationality or the place of residence of the service recipients”) found prima facie evidence for different treatment based on the place of residence of the customer across the four sectors covered in the study – car rental, digital download, online sale of electronic goods and tourism. ↩

-

For example, the European Parliament’s “Cost of Non-Europe – Digital Single Market” report identifies cloud computing as an area where there is limited uptake, noting that unclear, complex and legally uncertain contracts deter traders and individuals from using and adopting the cloud. They estimate that the ‘Costs of non-Europe’ in this area amount to €31.5 billion to €63 billion per annum. ↩