The United Kingdom’s exit from, and new partnership with, the European Union

Updated 15 May 2017

Foreword by the Prime Minister

We do not approach these negotiations expecting failure, but anticipating success.

Because we are a great, global nation with so much to offer Europe and so much to offer the world.

One of the world’s largest and strongest economies. With the nest intelligence services, the bravest armed forces, the most effective hard and soft power, and friendships, partnerships and alliances in every continent.

And another thing that’s important. The essential ingredient of our success. The strength and support of 65 million people willing us to make it happen.

Because after all the division and discord, the country is coming together.

The referendum was divisive at times. And those divisions have taken time to heal.

But one of the reasons that Britain’s democracy has been such a success for so many years is that the strength of our identity as one nation, the respect we show to one another as fellow citizens, and the importance we attach to our institutions means that when a vote has been held we all respect the result. The victors have the responsibility to act magnanimously. The losers have the responsibility to respect the legitimacy of the outcome. And the country comes together.

And that is what we are seeing today. Business isn’t calling to reverse the result, but planning to make a success of it. The House of Commons has voted overwhelmingly for us to get on with it. And the overwhelming majority of people – however they voted – want us to get on with it too.

So that is what we will do.

Not merely forming a new partnership with Europe, but building a stronger, fairer, more Global Britain too.

And let that be the legacy of our time. The prize towards which we work. The destination at which we arrive once the negotiation is done.

And let us do it not for ourselves, but for those who follow. For the country’s children and grandchildren too.

So that when future generations look back at this time, they will judge us not only by the decision that we made, but by what we made of that decision.

They will see that we shaped them a brighter future.

They will know that we built them a better Britain.

Prime Minister Rt Hon Theresa May MP, Lancaster House, 17 January 2017

Preface by the Secretary of State

The people of the United Kingdom (UK) have voted to leave the EU and this Government will respect their wishes. We will trigger Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union by the end of March 2017 to begin the process of exit. We will negotiate the right deal for the entire UK and in the national interest.

With our economy proving resilient, the UK enters these negotiations from a position of strength.

We approach these negotiations from a unique position. As things stand, we have the exact same rules, regulations and standards as the rest of the EU. Unlike most negotiations, these talks will not be about bringing together two divergent systems but about managing the continued cooperation of the UK and the EU. The focus will not be about removing existing barriers or questioning certain protections but about ensuring new barriers do not arise.

The links between the UK and the rest of Europe are numerous and longstanding – and go beyond just the EU. They range from our shared commitment to NATO to the shared values underpinning our societies, such as democracy and the rule of law.

The UK wants the EU to succeed. Indeed it is in our interests for it to prosper politically and economically and a strong new partnership with the UK will help to that end.

We hope that in the upcoming talks, the EU will be guided by the principles set out in the EU Treaties concerning a high degree of international cooperation and good neighbourliness.

On 17 January 2017 the Prime Minister set out the 12 principles which will guide the Government in fulfilling the democratic will of the people of the UK. These are:

- Providing certainty and clarity

- Taking control of our own laws

- Strengthening the Union

- Protecting our strong historic ties with Ireland and maintaining the Common Travel Area

- Controlling immigration

- Securing rights for EU nationals in the UK and UK nationals in the EU

- Protecting workers’ rights

- Ensuring free trade with European markets

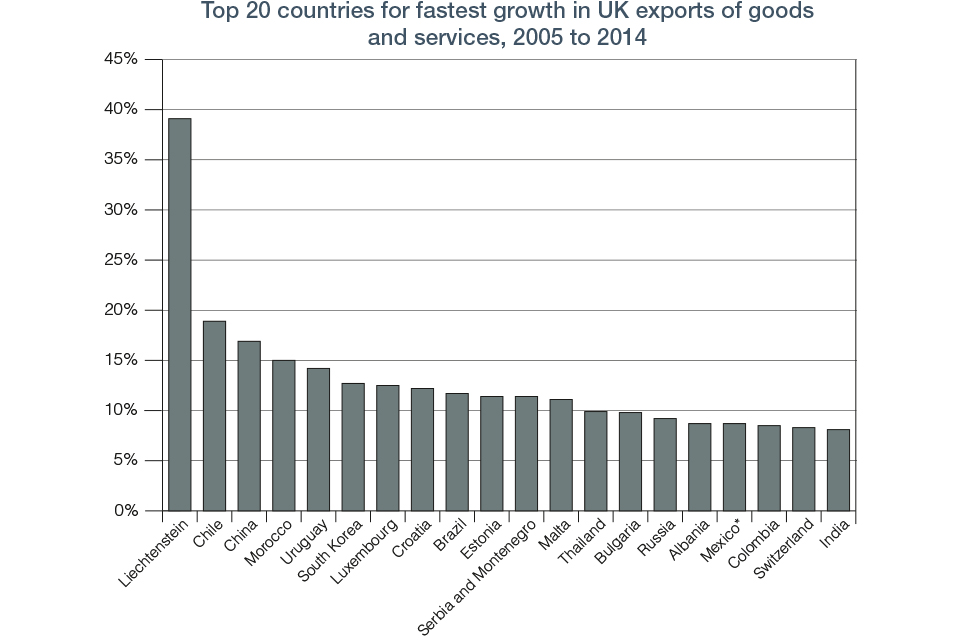

- Securing new trade agreements with other countries

- Ensuring the United Kingdom remains the best place for science and innovation

- Cooperating in the fight against crime and terrorism

- Delivering a smooth, orderly exit from the EU

In this paper we set out the basis for these 12 priorities and the broad strategy that unites them in forging a new strategic partnership between the United Kingdom and the EU.

We have respected the decision of Parliament that we should not publish detail that would undermine our negotiating position.

However, we are committed to extensive engagement with Parliament and to continuing the high degree of public engagement which has informed our position to date. We will continue to engage widely and seek to build a national consensus around our negotiating position.

The referendum result was not a vote to turn our back on Europe. Rather, it was a vote of confidence in the UK’s ability to succeed in the world – an expression of optimism that our best days are still to come.

This document sets out our plan for the strong new partnership we want to build with the EU. Whatever the outcome of our negotiations, we will seek a more open, outward-looking, con dent and fairer UK, which works for all.

Rt Hon David Davis MP, Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union

1. Providing certainty and clarity

We recognise how important it is to provide business, the public sector and the public with as much certainty as possible. So ahead of, and throughout the negotiations, we will provide certainty wherever we can. We will provide as much information as we can without undermining the national interest.

Providing legal certainty

1.1 To provide legal certainty over our exit from the EU, we will introduce the Great Repeal Bill to remove the European Communities Act 1972 from the statute book and convert the ‘acquis’ – the body of existing EU law – into domestic law. This means that, wherever practical and appropriate, the same rules and laws will apply on the day after we leave the EU as they did before.

1.2 This approach will preserve the rights and obligations that already exist in the UK under EU law and provide a secure basis for future changes to our domestic law. This allows businesses to continue trading in the knowledge that the rules will not change significantly overnight and provides fairness to individuals whose rights and obligations will not be subject to sudden change. It will also be important for business in both the UK and the EU to have as much certainty as possible as early as possible.

1.3 Once we have left the EU, Parliament (and, where appropriate, the devolved legislatures) will then be able to decide which elements of that law to keep, amend or repeal.

1.4 We will bring forward a White Paper on the Great Repeal Bill that provides more detail about our approach.

1.5 Domestic legislation will also need to reflect the content of the agreement we intend to negotiate with the EU.

The Great Repeal Bill

The Great Repeal Bill was announced to Parliament on 10 October 2016. The Bill has three primary elements:

-

First, it will repeal the European Communities Act 1972, and in so doing, return power to UK politicians and institutions.

-

Second, the Bill will preserve EU law where it stands at the moment before we leave the EU. Parliament (and, where appropriate, the devolved legislatures) will then be able to decide which elements of that law to keep, amend or repeal once we have left the EU - the UK courts will then apply those decisions of Parliament and the devolved legislatures.

-

Finally, the Bill will enable changes to be made by secondary legislation to the laws that would otherwise not function sensibly once we have left the EU, so that our legal system continues to function correctly outside the EU.

The Government’s general approach to preserving EU law is to ensure that all EU laws which are directly applicable in the UK (such as EU regulations) and all laws which have been made in the UK, in order to implement our obligations as a member of the EU, remain part of domestic law on the day we leave the EU.

In general the Government also believes that the preserved law should continue to be interpreted in the same way as it is at the moment. This approach is in order to ensure a coherent approach which provides continuity. It will be open to Parliament in the future to keep or change these laws.

Public and parliamentary involvement and scrutiny

1.6 We will continue to build a national consensus around our negotiating position by listening and talking to as many organisations, companies and institutions as possible. Government ministers have led widespread engagement with their sectors and ministers from the Department for Exiting the EU alone have held around 150 stakeholder engagement events, covering all sectors of the economy. The majority have been outside London and right across the UK, including Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England. This has helped inform Government understanding of the key issues for business and other stakeholders ahead of the negotiations. This engagement will continue throughout the period before we leave.

1.7 The devolved administrations will continue to be engaged through the Joint Ministerial Committee (JMC), chaired in plenary by the Prime Minister and attended by the First Ministers of Scotland and Wales and the First and deputy First Ministers of Northern Ireland, and the JMC sub-committee on EU Negotiations (JMC(EN)), chaired by the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, with members from each of the UK devolved administrations.

1.8 Parliament also has a critical role. First, legislation will be needed to give effect to our withdrawal from the EU and the content of such legislation will of course be determined by Parliament. This includes the Great Repeal Bill, but any significant policy changes will be underpinned by other primary legislation – allowing Parliament the opportunity to debate and scrutinise the changes. For example, we expect to bring forward separate bills on immigration and customs. There will also be a programme of secondary legislation under the Great Repeal Bill to address deficiencies in the preserved law, which will be subject to parliamentary oversight.

1.9 Both Houses, the House of Commons Select Committee on Exiting the EU and other select committees will help to scrutinise and inform the decisions made. Since September, and in addition to debates that have been scheduled by opposition parties or the Backbench Business Committee, and debates in the House of Lords, the Government has provided for four debates in the House of Commons in Government time on the impact of EU exit on a variety of sectors, such as:

- workers’ rights

- transport policy

- science and research

- security, law enforcement and criminal justice

That programme of debates will continue.

1.10 The Government has made five Oral Statements to Parliament on the subject of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU and answered over 500 Parliamentary Questions. Ministers from the Department for Exiting the EU have also appeared 12 times in front of select committees, and those committees have undertaken, or are currently undertaking, 36 inquiries on EU exit-related issues. Government ministers will continue to provide regular updates to Parliament and the Government will continue to ensure that there is ample opportunity for both Houses to debate the key issues arising from EU exit.

1.11 To enable the Government to achieve the best outcome in the negotiations, we will need to keep our positions closely held and will need at times to be careful about the commentary we make public. Our fundamental responsibility to the people of the UK is to ensure that we secure the very best deal possible from the negotiations. We will, however, ensure that the UK Parliament receives at least as much information as that received by members of the European Parliament.

1.12 The Government will then put the final deal that is agreed between the UK and the EU to a vote in both Houses of Parliament.

Funding commitments

1.13 We recognise the importance to business of having certainty about funding arrangements over the coming years. We have already acted quickly to give clarity about farm payments, competitive grants, including science and research funding, and structural and investment funds.

Funding commitments already made by this Government

All European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIFs) projects signed, or with funding agreements that were in place before the Autumn Statement 2016, will be fully funded, even when these projects continue beyond the UK’s departure from the EU. This includes agri-environment schemes under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

For projects signed after the Autumn Statement 2016 and which continue after we have left the EU, HM Treasury will honour funding for projects if they provide strong value for money and are in line with domestic strategic priorities.

For bids made directly to the Commission by UK organisations (including for Horizon 2020, the EU’s research and innovation programme and in funds for health and education), institutions, universities and businesses should continue to bid for funding. We will work with the Commission to ensure payment when funds are awarded. HM Treasury will underwrite the payment of such awards, even when specific projects continue beyond the UK’s departure from the EU.

HM Treasury has also provided a guarantee to the agricultural sector that it will receive the same level of funding that it would have received under Pillar 1 of CAP until the end of the Multiannual Financial Framework in 2020.

In the case of the devolved administrations, we are offering the same level of reassurance as we are offering to UK government departments in relation to programmes they administer, but for which they expected to rely on EU funding.

The Government will consult closely with stakeholders to review all EU funding schemes in the round, to ensure any ongoing funding commitments best serve the UK’s national interests.

2. Taking control of our own laws

We will take control of our own affairs, as those who voted in their millions to leave the EU demanded we must, and bring an end to the jurisdiction in the UK of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

Parliamentary sovereignty

2.1 The sovereignty of Parliament is a fundamental principle of the UK constitution. Whilst Parliament has remained sovereign throughout our membership of the EU, it has not always felt like that. The extent of EU activity relevant to the UK can be demonstrated by the fact that 1,056 EU-related documents were deposited for parliamentary scrutiny in 2016. These include proposals for EU Directives, Regulations, Decisions and Recommendations, as well as Commission delegated acts, and other documents such as Commission Communications, Reports and Opinions submitted to the Council, Court of Auditors Reports and more.

2.2 Leaving the EU will mean that our laws will be made in London, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast, and will be based on the specific interests and values of the UK. In chapter 1 we set out how the Great Repeal Bill will ensure that our legislatures and courts will be the final decision makers in our country.

Ending the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the European Union in the UK

2.3 The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is the EU’s ultimate arbiter on matters of EU law. As a supranational court, it aims to provide both consistent interpretation and enforcement of EU law across all 28 Member States and a clear process for dispute resolution when disagreements arise. The CJEU is amongst the most powerful of supranational courts due to the principles of primacy and direct effect in EU law. We will bring an end to the jurisdiction of the CJEU in the UK. We will of course continue to honour our international commitments and follow international law.

Dispute resolution mechanisms

2.4 We recognise that ensuring a fair and equitable implementation of our future relationship with the EU requires provision for dispute resolution.

2.5 Dispute resolution mechanisms ensure that all parties share a single understanding of an agreement, both in terms of interpretation and application. These mechanisms can also ensure uniform and fair enforcement of agreements.

2.6 Such mechanisms are common in EU-Third Country agreements. For example, the new EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) established a ‘CETA Joint Committee’[footnote 1] to supervise the implementation and application of the agreement. Parties can refer disputes to an ad hoc arbitration panel if necessary. The Joint Committee can decide on interpretations that are binding on the interpretation panels[footnote 2]. Similarly, the EU’s free trade agreement with South Korea also provides for an arbitration system where disputes arise[footnote 3].

2.7 Dispute resolution mechanisms are also common in other international agreements. Under the main dispute settlement procedure in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the governments concerned aim to resolve any potential disputes amicably, but if that is not possible, there are expeditious and effective panel procedures. Similarly, under the treaties establishing Mercosur, disputes are in the first instance resolved politically, but otherwise the parties can submit the dispute to an ad hoc arbitration tribunal. Decisions of the tribunal may be appealed on a point of law to a Permanent Review Tribunal Under the New Zealand-Korea Free Trade Agreement, where the focus is also on cooperation and consultation to reach a mutually satisfactory outcome. The agreement sets out a process for the establishment of an arbitration panel. The parties must comply with its findings and rulings, otherwise compensation may be payable or the benefits of the FTA may be suspended. Within the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the Dispute Settlement Body (made up of all the members of the WTO) decides on disputes between members relating to WTO agreements[footnote 4]. Recommendations are made by dispute settlement panels or by an Appellate Body which can uphold, modify or reverse the decisions reached by the panel. Such mechanisms are essential to ensuring fair interpretation and application of international agreements.

2.8 The UK already has a number of dispute resolution mechanisms in its international arrangements. The same is true for the EU. Unlike decisions made by the CJEU, dispute resolution in these agreements does not have direct effect in UK law.

2.9 As with any wide-ranging agreement between states, the UK will seek to agree a new approach to interpretation and dispute resolution with the EU. This is essential to reassure businesses and individuals that the terms of any agreement can be relied upon, that both parties will have a common understanding of what the agreement means and that disputes can be resolved fairly and efficiently.

2.10 There are a number of examples that illustrate how other international agreements approach interpretation and dispute resolution[footnote 5]. Some of these are set out in Annex A. Of course, these serve only as examples of current practice. The actual form of dispute resolution in a future relationship with the EU will be a matter for negotiations between the UK and the EU, and we should not be constrained by precedent. Different dispute resolution mechanisms could apply to different agreements, depending on how the new relationship with the EU is structured. Any arrangements must be ones that respect UK sovereignty, protect the role of our courts and maximise legal certainty, including for businesses, consumers, workers and other citizens.

3. Strengthening the Union

It is more important than ever that we face the future together, united by what makes us strong: the bonds that unite us, and our shared interest in the UK being an open, successful trading nation.

3.1 We have ensured since the referendum that the devolved administrations are fully engaged in our preparations to leave the EU and we are working with the administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to deliver an outcome that works for the whole of the UK. In seeking such a deal we will look to secure the specific interests of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, as well as those of all parts of England. A good deal will be one that works for all parts of the UK.

3.2 The Prime Minister has already chaired two plenary meetings of the Joint Ministerial Committee, which brings together the leaders of the devolved administrations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The first meeting agreed to set up a Joint Ministerial Committee on EU Negotiations (JMC(EN)), so ministers from each of the devolved administrations can contribute to the process of planning for our departure from the EU. At the January plenary session of the Joint Ministerial Committee, ministers agreed to intensify their work ahead of the triggering of Article 50 and to continue at the same pace thereafter.

The Joint Ministerial Committee on EU Negotiations (JMC(EN))

The JMC(EN) is chaired by the Secretary of State for Exiting the EU and its members include ministers from each of the UK devolved administrations.

JMC(EN) has met on a monthly basis since its inception, and will continue to meet regularly to understand and consider each administration’s priorities; to seek to agree a UK approach to, and objectives for, negotiations, and to consider proposals put forward by the devolved administrations.

At the first meeting, held in November, ministers set out their priorities for discussion at JMC(EN) and agreed to develop further the proposed work programme to ensure its connection to and involvement with the process of negotiations. Ministers agreed to meet monthly to share evidence and to take forward joint analysis, which would inform that work programme.

At the second meeting, held in December, ministers discussed their priorities relating to law enforcement, security and criminal justice, civil judicial cooperation, immigration and trade. There was a follow up discussion from the last meeting of JMC(EN) on market access. Ministers agreed that officials should take forward joint analysis across the range of issues being considered by JMC(EN) and captured in the work programme. Ministers agreed to continue to engage bilaterally ahead of the next meeting in January.

At the third meeting in January, the Scottish Government presented its paper on Scotland’s Place in Europe and the Committee agreed to undertake bilateral official-level discussions on the Scottish Government proposals.

UK government departments also continue their significant bilateral engagement on the key issues relating to the UK’s withdrawal from the EU and on ongoing business.

3.3 The current devolution settlements were created in the context of the UK’s membership of the EU. All three settlements set out that devolved legislatures only have legislative competence – the ability to make law – in devolved policy areas as long as that law is compatible with EU law.

3.4 This has meant that, even in areas where the devolved legislatures and administrations currently have some competence, such as agriculture, environment and some transport issues, most rules are set through common EU legal and regulatory frameworks, devised and agreed in Brussels. When the UK leaves the EU, these rules will be set here in the UK by democratically elected representatives.

3.5 As the powers to make these rules are repatriated to the UK from the EU, we have an opportunity to determine the level best placed to make new laws and policies on these issues, ensuring power sits closer to the people of the UK than ever before. We have already committed that no decisions currently taken by the devolved administrations will be removed from them and we will use the opportunity of bringing decision making back to the UK to ensure that more decisions are devolved.

The recent history of devolution

The UK’s constitutional arrangements have evolved over time and been adapted to reflect the unique circumstances of the world’s most successful and enduring multi-nation state. These arrangements provide all of the UK with the space to pursue different domestic policies should they wish to, whilst protecting and preserving the benefits of being part of the wider UK.

The current arrangements for governing the UK have been in place for almost 20 years. In September 1997, referendums were held in Scotland and Wales and a majority of voters chose to establish a Scottish Parliament and a National Assembly for Wales. In Northern Ireland, devolution was a key part of the Belfast Agreement, which was supported by voters in a referendum in May 1998. The UK Parliament passed legislation in 1998 to establish the three devolved legislatures and administrations and set out their powers. Throughout the last two decades, the settlements have continued to evolve; for example, new tax raising powers were devolved to the Scottish Parliament under the Scotland Act 2016 and the model of Welsh devolution was altered by the Wales Act 2017.

The UK Government acts in the interests of the whole UK and is responsible for the UK’s international relations, including negotiations with the EU. It transacts those responsibilities in close consultation with the devolved administrations, underpinned by the principles set out in the Memorandum of Understanding agreed by all the administrations.

3.6 We must also recognise the importance of trade within the UK to all parts of the Union. For example, Scotland’s exports to the rest of the UK are estimated to be four times greater than those to the EU27 (in 2015, £49.8 billion compared with £12.3 billion).[footnote 6] So our guiding principle will be to ensure that – as we leave the EU – no new barriers to living and doing business within our own Union are created. We will maintain the necessary common standards and frameworks for our own domestic market, empowering the UK as an open, trading nation to strike the best trade deals around the world and protecting our common resources.

3.7 On the basis of these principles, we will work with the devolved administrations on an approach to returning powers from the EU that works for the whole of the UK and reflects the interests of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

3.8 We will also continue to champion devolution to local government and are committed to devolving greater powers to local government where there is economic rationale to do so.

Devolved administrations’ proposals

In addition to the broad programme of engagement through JMC(EN), the UK Government has committed to examine any proposals brought forward by the devolved administrations. To date papers have been published by the Scottish and Welsh Governments.

In December, the Scottish Government published Scotland’s Place in Europe[footnote 7], which was presented to JMC(EN) in January.

The paper set out three priorities:

- influencing the overall UK position so that the UK remains in the European Single Market, through the European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement and also in the EU Customs Union

- exploring differentiated options for how Scotland could remain a member of the European Single Market and retain aspects of EU membership, even if the rest of the UK leaves

- safeguarding and significantly expanding the powers of the Scottish Parliament

The UK and Scottish Governments are taking forward further discussions on the proposals detailed in the paper.

In January, the Welsh Government published Securing Wales’ Future,[footnote 8] which set out a joint position with Plaid Cymru. The paper, which will be discussed at a future JMC(EN) meeting, set out the Welsh Government’s views on six areas:

- the importance of continued participation in the Single Market

- a balanced approach to immigration linking migration to jobs and good, properly enforced employment practices

- on finance and investment, Wales should not lose funding as a result of the UK leaving the EU

- a fundamentally different constitutional relationship between the devolved governments and the UK Government

- maintaining social and environmental protections

- proper consideration of transitional arrangements

The Northern Ireland Executive has not published a White Paper on EU exit. However, the former First and deputy First Ministers wrote to the Prime Minister setting out the key priorities for Northern Ireland last August. Ministers from the Northern Ireland Executive have participated in JMC(EN) discussions and presented evidence on the impact of EU exit in Northern Ireland and the priorities for Northern Ireland from the new relationship with the EU.

Bilateral discussions will now be taken forward between each of the devolved administrations and the UK Government to fully understand their priorities, which will inform the continuing discussions.

There are many areas where the devolved administrations and the UK Government agree, including on the importance of providing certainty for businesses across the UK, maintaining strong trading links with the EU, protecting the status of EU nationals in the UK and UK nationals in the EU and protecting workers’ rights.

3.9 As the UK leaves the EU, the unique relationships that the Crown Dependencies of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands and the Overseas Territories have with the EU will also change. Gibraltar will have particular interests, given that the EU Treaties apply to a large extent in Gibraltar, with some exceptions (for example, Gibraltar is not part of the Customs Union).[footnote 8]

3.10 We have ensured that their priorities are understood through a range of engagement including new fora dedicated to discussing the impact of EU exit: the Joint Ministerial Council on EU Negotiations, with representatives of the governments of the Overseas Territories, a new Joint Ministerial Council (Gibraltar EU Negotiations) with the Government of Gibraltar, and formal quarterly meetings with the Chief Ministers of the Crown Dependencies. We will continue to involve them fully in our work, respect their interests and engage with them as we enter negotiations, and strengthen the bonds between us as we forge a new relationship with the EU and look outward into the world.

4. Protecting our strong and historic ties with Ireland and maintaining the Common Travel Area

Maintaining our strong and historic ties with Ireland will be an important priority for the UK in the talks ahead. This includes protecting the Common Travel Area (CTA).

4.1 The UK and Ireland are inescapably intertwined through our shared history, culture and geography. It is a unique relationship: there are hundreds of thousands of Irish nationals residing in the UK and of UK nationals residing in Ireland. There are also close ties and family connections, particularly across the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland. Further information is provided in Annex B.

4.2 The relationship between the two countries has never been better or more settled than today, thanks to the strong political commitment from both Governments to deepen and broaden our modern partnership. Two recent State Visits, by Her Majesty The Queen in May 2011 and by President Higgins in April 2014, have helped cement this partnership; no one wants to see a return to the borders of the past. The Prime Minister is committed to maintaining the closest of ties and has already met the Taoiseach several times since taking office, most recently in Dublin in January 2017.

Economic ties

4.3 The UK and Irish economies are deeply integrated, through trade and cross-border investments, as well as through the free flow of goods, utilities, services and people. Annual trade between the UK and Ireland stands at over £43 billion,[footnote 9] while around 60 per cent of Northern Ireland’s goods exports to the EU are to Ireland.[footnote 10],[footnote 11] Cross-border movement of people is an important part of this economic integration. Over 14,000 people regularly commute across the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland for work or study.[footnote 12]

4.4 We recognise that for the people of Northern Ireland and Ireland, the ability to move freely across the border is an essential part of daily life. When the UK leaves the EU we aim to have as seamless and frictionless a border as possible between Northern Ireland and Ireland, so that we can continue to see the trade and everyday movements we have seen up to now.

4.5 We will work closely to ensure that, as the UK leaves the EU, we find shared solutions to the economic challenges and maximise the economic opportunities for both the UK and Ireland.

Rights

4.6 The close historic, social and cultural ties between the UK and Ireland predate both countries’ membership of the EU and have led to the enjoyment of additional rights beyond those associated with common membership of the EU. The special status afforded to Irish citizens within the UK is rooted in the Ireland Act 1949 and, for the people of Northern Ireland, in the 1998 Belfast Agreement.

4.7 Both the UK and Irish Governments have set out their desire to protect this reciprocal treatment of each other’s nationals once the UK has left the EU. In particular, in recognition of their importance in the Belfast Agreement, the people of Northern Ireland will continue to be able to identify themselves as British or Irish, or both, and to hold citizenship accordingly.

The Common Travel Area (CTA)

The CTA is a special travel zone for the movement of people between the UK, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. It was formed long before the UK and Ireland were members of the EU and reflects the deep-rooted, historical ties provided for by the free movement of respective members’ nationals within the CTA and the synergies between our countries. We are committed to protecting this arrangement.

The adoption of the CTA was linked to the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, with separate legislative provision for the Crown Dependencies in 1919 and 1920. It originally arose as an administrative practice allowing free travel between CTA countries. It has since been reflected in each state’s application of national immigration policy, with all countries pursuing a common approach. With the exception of a short period during the Second World War there have not been immigration controls on journeys between CTA members.

Protocol 22 of the EU Treaties provides that the UK and Ireland may continue to make arrangements between themselves relating to the movement of people within the CTA. Nationals of CTA members can travel freely within the CTA to the UK without being subject to routine passport controls.

4.8 We want to protect the ability to move freely between the UK and Ireland, north-south and east-west, recognising the special importance of this to people in their daily lives. We will work with the Northern Ireland Executive, the Irish Government and the Crown Dependencies to deliver a practical solution that allows for the maintenance of the CTA, while protecting the integrity of the UK’s immigration system.

Our commitment

4.9 We are determined that our record of collaboration, built on shared experience and values and supported by personal, political and economic ties, continues to develop and strengthen after we leave the EU.

4.10 We will work with the Irish Government and the Northern Ireland Executive to find a practical solution that recognises the unique economic, social and political context of the land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland. An explicit objective of the UK Government’s work on EU exit is to ensure that full account is taken for the particular circumstances of Northern Ireland. We will seek to safeguard business interests in the exit negotiations. We will maintain close operational collaboration between UK and Irish law enforcement and security agencies and their judicial counterparts.

5. Controlling immigration

We will remain an open and tolerant country, and one that recognises the valuable contribution migrants make to our society and welcomes those with the skills and expertise to make our nation better still. But in future we must ensure we can control the number of people coming to the UK from the EU.

5.1 As we leave the EU and embrace the world, openness to international talent will remain one of our most distinctive assets.

5.2 We welcome the contribution that migrants have brought and will continue to bring to our economy and society. That is why we will always want immigration, including from EU countries, and especially high-skilled immigration and why we will always welcome individual migrants arriving lawfully in the UK as friends.

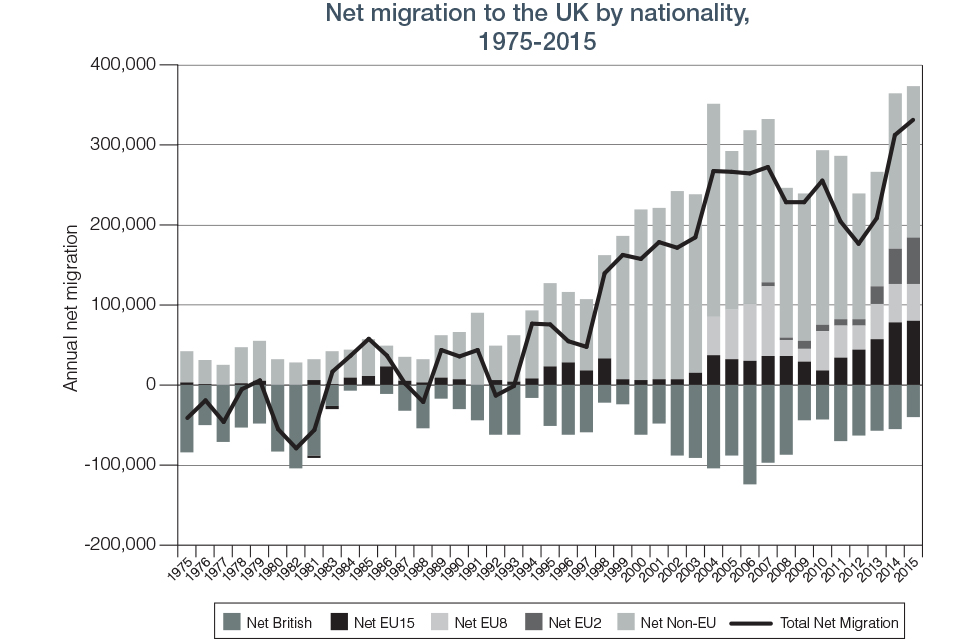

5.3 However, in the last decade or so, we have seen record levels of long term net migration in the UK,[footnote 13] and that sheer volume has given rise to public concern about pressure on public services, like schools and our infrastructure, especially housing, as well as placing downward pressure on wages for people on the lowest incomes. The public must have confidence in our ability to control immigration. It is simply not possible to control immigration overall when there is unlimited free movement of people to the UK from the EU.

5.4 We will design our immigration system to ensure that we are able to control the numbers of people who come here from the EU. In future, therefore, the Free Movement Directive will no longer apply and the migration of EU nationals will be subject to UK law.

Chart 5.1 – Net migration to the UK

Source – ONS[footnote 14]

Our approach to controlling migration

5.5 Immigration can bring great benefits – filling skills shortages, delivering public services and making the UK’s businesses the world-beaters they often are. But it must be controlled.

5.6 We will create an immigration system that allows us to control numbers and encourage the brightest and the best to come to this country, as part of a stable and prosperous future with the EU and our European partners.

5.7 The UK will always welcome genuine students and those with the skills and expertise to make our nation better still. We have already confirmed that existing EU students and those starting courses in 2016-17 and 2017-18 will continue to be eligible for student loans and home fee status for the duration of their course. We have also confirmed that research councils will continue to fund postgraduate students from the EU whose courses start in 2017-18.

5.8 The Government also recognises the important contribution made by students and academics from EU Member States to the UK’s world class universities. A global UK must also be a country that looks to the future.

5.9 We are considering very carefully the options that are open to us to gain control of the numbers of people coming to the UK from the EU. As part of that, it is important that we understand the impacts on the different sectors of the economy and the labour market. We will, therefore, ensure that businesses and communities have the opportunity to contribute their views. Equally, we will need to understand the potential impacts of any proposed changes in all the parts of the UK. So we will build a comprehensive picture of the needs and interests of all parts of the UK and look to develop a system that works for all.

5.10 Implementing any new immigration arrangements for EU nationals and the support they receive will be complex and Parliament will have an important role in considering these matters further. There may be a phased process of implementation to prepare for the new arrangements. This would give businesses and individuals enough time to plan and prepare for those new arrangements.

Free movement of people

The main EU Treaty provisions relevant to the free movement of people (and associated provisions on social security and welfare provision in cross-border situations) are:

- Article 18 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) on non-discrimination

- Articles 20 and 21 TFEU which deal with EU citizenship and free movement rights

- Articles 45-48 TFEU on the free movement of workers and social security coordination

- Articles 49-53 TFEU as they relate to the freedom of establishment of self-employed persons

Free movement rights can be exercised by EU citizens, their dependants and – in certain circumstances – other family members. These rights are largely set out in the EU Treaties and in secondary EU legislation. These rights have also been extended to nationals of the European Economic Area (EEA) states who are not members of the EU (Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein) and to Switzerland by virtue of two separate agreements. EU citizens also have the right to exercise free movement rights in these states.

EU secondary legislation provides further detail on the rights contained in the EU Treaties. There are key pieces of secondary EU legislation that are most relevant. The Free Movement Directive[footnote 15] sets out the rights of EU citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the EU. This Directive replaced most of the previous European legislation facilitating the migration of the economically active and it consolidated the rights of EU citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the EU. The Directive is implemented in the UK via the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2016, which also apply to Swiss nationals and nationals of those EEA States which are not EU Member States.

6. Securing rights for EU nationals in the UK, and UK nationals in the EU

We want to secure the status of EU citizens who are already living in the UK, and that of UK nationals in other Member States, as early as we can.

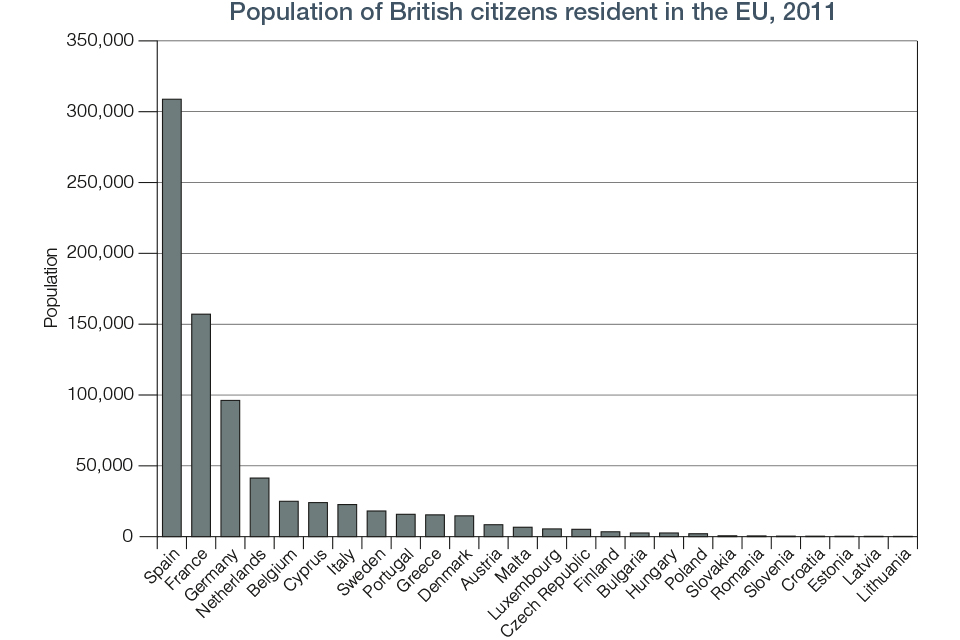

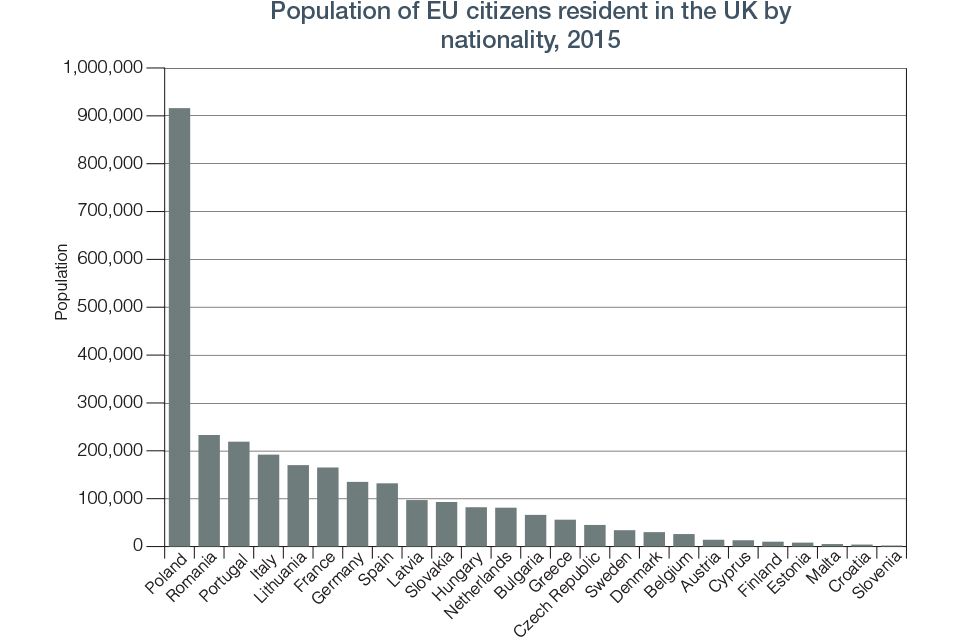

6.1 Around 2.8 million EU nationals[footnote 16] were estimated to be resident in the UK, many of whom originate from Poland.[footnote 17] It is estimated that around 1 million UK nationals are long-term residents of other EU countries, including around 300,000 in Spain. France and Germany also host large numbers of British citizens.[footnote 18]

Chart 6.1 – British citizens resident in the EU

Source – ONS[footnote 19],[footnote 20]

6.2 While we are a member of the EU, the rights of EU nationals living in the UK and UK nationals living in the EU remain unchanged. As provided for in both the EU Free Movement Directive (Article 16 of 2004/38/EC) and in UK law, those who have lived continuously and lawfully in a country for at least five years automatically have a permanent right to reside. We recognise the contribution EU nationals have made to our economy and communities.

Chart 6.2 – EU nationals resident in the UK

Source – ONS[footnote 21],[footnote 22]

6.3 Securing the status of, and providing certainty to, EU nationals already in the UK and to UK nationals in the EU is one of this Government’s early priorities for the forthcoming negotiations. To this end, we have engaged a range of stakeholders, including expatriate groups, to ensure we understand the priorities of UK nationals living in EU countries. This is part of our preparations for a smooth and orderly withdrawal and we will continue to work closely with a range of organisations and individuals to achieve this. For example, we recognise the priority placed on easy access to healthcare by UK nationals living in the EU. We are also engaging closely with EU Member States, businesses and other organisations to ensure that we have a thorough understanding of issues concerning the status of EU nationals in the UK.

6.4 The Government would have liked to resolve this issue ahead of the formal negotiations. And although many EU Member States favour such an agreement, this has not proven possible. The UK remains ready to give people the certainty they want and reach a reciprocal deal with our European partners at the earliest opportunity. It is the right and fair thing to do.

7. Protecting workers’ rights

UK employment law already goes further than many of the standards set out in EU legislation and this Government will protect and enhance the rights people have at work.

7.1 As we convert the body of EU law into our domestic legislation, we will ensure the continued protection of workers’ rights. This will give certainty and continuity to employees and employers alike, creating stability in which the UK can grow and thrive.

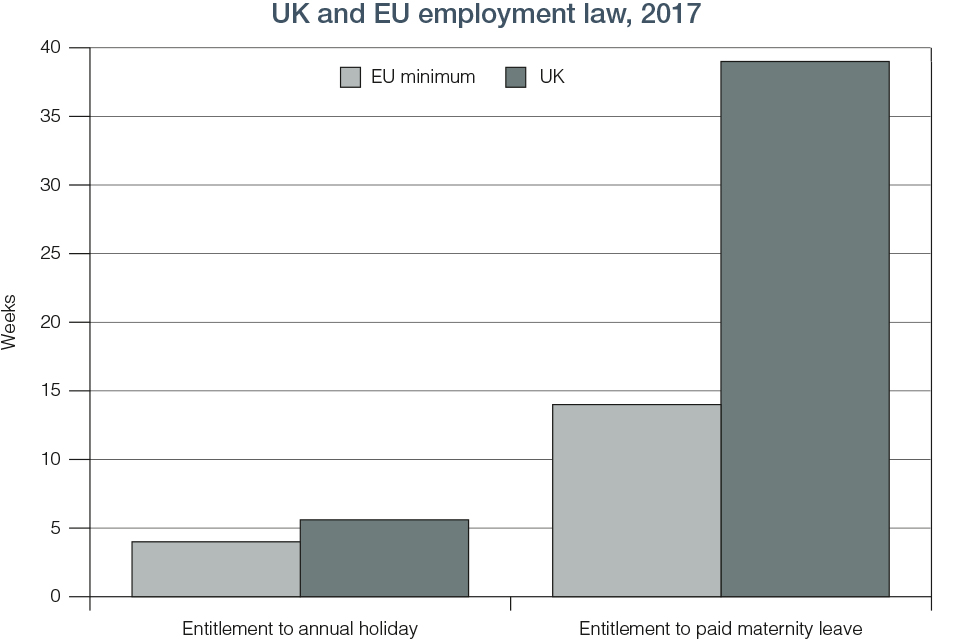

7.2 Our labour market is a great strength of our economy: there are 31.8 million people in work in the UK and the employment rate is at a near-record high.[footnote 23] The Great Repeal Bill will maintain the protections and standards that benefit workers. Moreover, this Government has committed not only to safeguard the rights of workers set out in European legislation, but to enhance them. The past few years have seen a number of independent actions by the Government to protect UK workers and ensure they are being treated fairly, and in many areas the UK Government has already extended workers’ rights beyond those set out in EU law. For example, UK domestic law already provides for 5.6 weeks of statutory annual leave,[footnote 24] compared to the four weeks set out in EU law.[footnote 25] In the UK, women who have had a child can enjoy 52 weeks of statutory maternity leave and 39 weeks of pay,[footnote 26] not just the 14 weeks under EU law.[footnote 27] The UK also provides greater flexibility around shared parental leave, where, subject to certain conditions, parental leave can be shared by the father of a child, giving families choice as to how they balance their home and work responsibilities. In addition, the UK offers 18 weeks’ parental leave, and that provision goes beyond the EU directive because it is available until the child’s 18th birthday.[footnote 28]

Chart 7.1 – UK and EU employment law

Source – HM Government and European Commission[footnote 29],[footnote 30]

7.3 These rights were the result of UK Government actions and do not depend on membership of the EU. The Government is committed to strengthening rights when it is the right choice for UK workers and will continue to seek out opportunities to enhance protections.

7.4 In April 2016 we introduced the National Living Wage and saw a 6.2 per cent pay increase for the lowest paid workers in our country over the previous year.[footnote 31] We have complemented this measure with strong enforcement action, increasing the enforcement budget for the National Minimum and Living Wage to £20 million for 2016/17, up from £13 million in 2015/16.[footnote 32]

7.5 We have increased penalties for wilfully non-compliant employers and have set up a dedicated team to tackle the more serious cases. Furthermore, we are appointing a statutory Director of Labour Market Enforcement and Exploitation. These actions demonstrate our commitment to ensuring that hard working people are entitled to a fair wage and that they receive the pay to which they are entitled.

7.6 We are committed to maintaining our status as a global leader on workers’ rights and will make sure legal protection for workers keeps pace with the changing labour market. Specifically, an independent review of employment practices in the modern economy is now underway.[footnote 33] The review will consider how employment rules need to change in order to keep pace with modern business models, such as: the rapid recent growth in self-employment; the shift in business practice from hiring to contracting; the rising use of non-standard contract forms and the emergence of new business models such as on-demand platforms.

7.7 Moreover, we will ensure that the voices of workers are heard by the boards of publicly-listed companies for the first time. We need business to be open, transparent and run for the benefit of all, not just a privileged few. It is for this reason that we launched a Green Paper on corporate governance in November 2016.[footnote 34] This paper seeks a wide range of views on our current corporate governance regime, and particularly on executive pay, employee and customer voice and corporate governance in large private businesses. It represents a decisive step towards corporate governance reform and is yet another example of this Government’s commitment to building an economy that works for everyone, not just those at the top.

8. Ensuring free trade with European markets

The Government will prioritise securing the freest and most frictionless trade possible in goods and services between the UK and the EU. We will not be seeking membership of the Single Market, but will pursue instead a new strategic partnership with the EU, including an ambitious and comprehensive Free Trade Agreement and a new customs agreement.

8.1 It is in the interests of the EU and all parts of the UK for the deeply integrated trade and economic relationship between the UK and EU to be maintained after our exit from the EU. Our new relationship should aim for the freest possible trade in goods and services between the UK and the EU. It should give UK companies the maximum freedom to trade with and operate within European markets and let European businesses do the same in the UK. This should include a new customs agreement with the EU, which will help to support our aim of trade with the EU that is as frictionless as possible.

8.2 We do not seek to adopt a model already enjoyed by other countries. The UK already has zero tariffs on goods and a common regulatory framework with the EU Single Market. This position is unprecedented in previous trade negotiations. Unlike other trade negotiations, this is not about bringing two divergent systems together. It is about finding the best way for the benefit of the common systems and frameworks, that currently enable UK and EU businesses to trade with and operate in each others’ markets, to continue when we leave the EU through a new comprehensive, bold and ambitious free trade agreement.

8.3 That agreement may take in elements of current Single Market arrangements in certain areas as it makes no sense to start again from scratch when the UK and the remaining Member States have adhered to the same rules for so many years. Such an arrangement would be on a fully reciprocal basis and in our mutual interests.

UK and EU trade

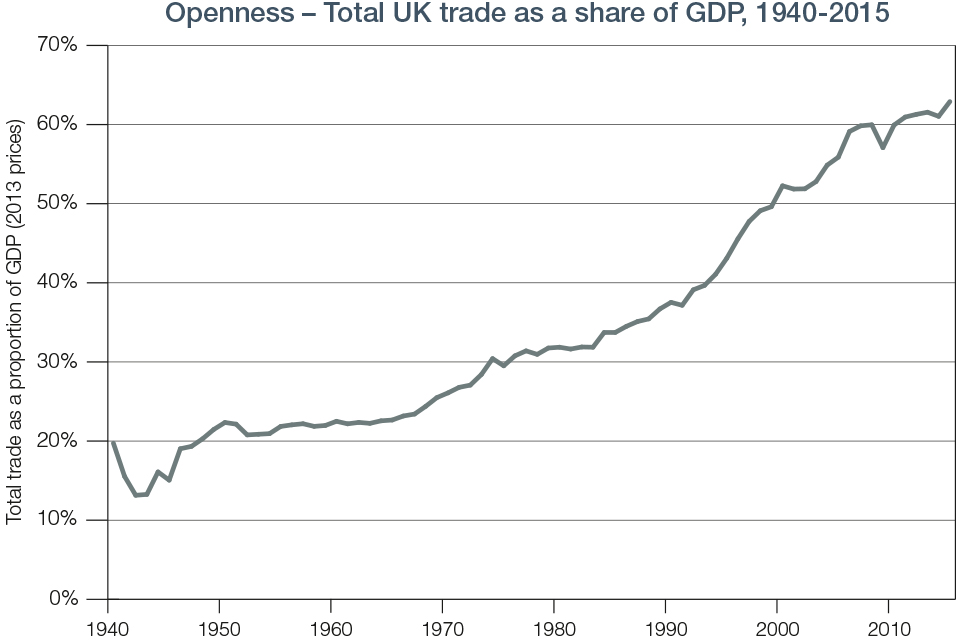

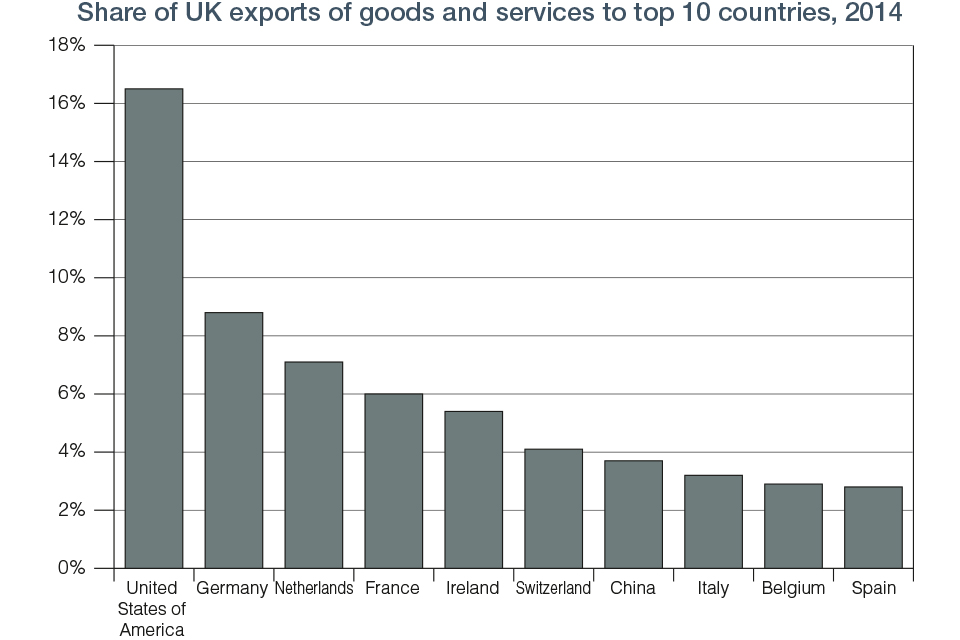

8.4 Both the UK and EU Member States benefit from our close trading relationship. The EU is the UK’s largest export market[footnote 35] and the UK is the largest goods export market for the EU27 taken as a whole.[footnote 36] However, the EU currently exports more to the UK than vice versa. In 2015, while the UK exported £230 billion worth of goods and services to the EU, the UK imported £291 billion worth of goods and services from the EU.[footnote 37] The UK’s £61 billion trade deficit with the EU was made up of an £89 billion deficit in goods and a £28 billion surplus in services.[footnote 38]

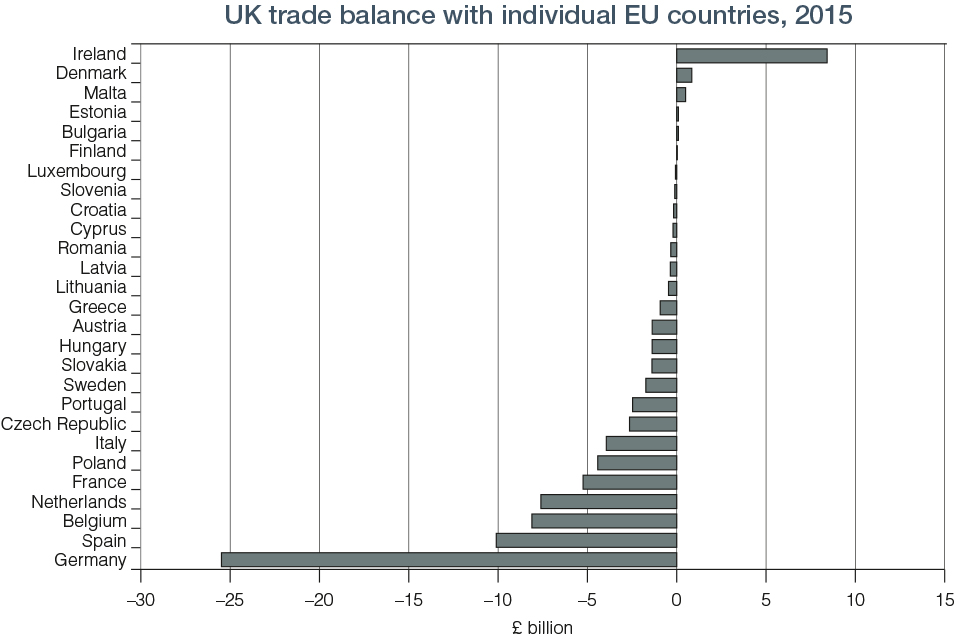

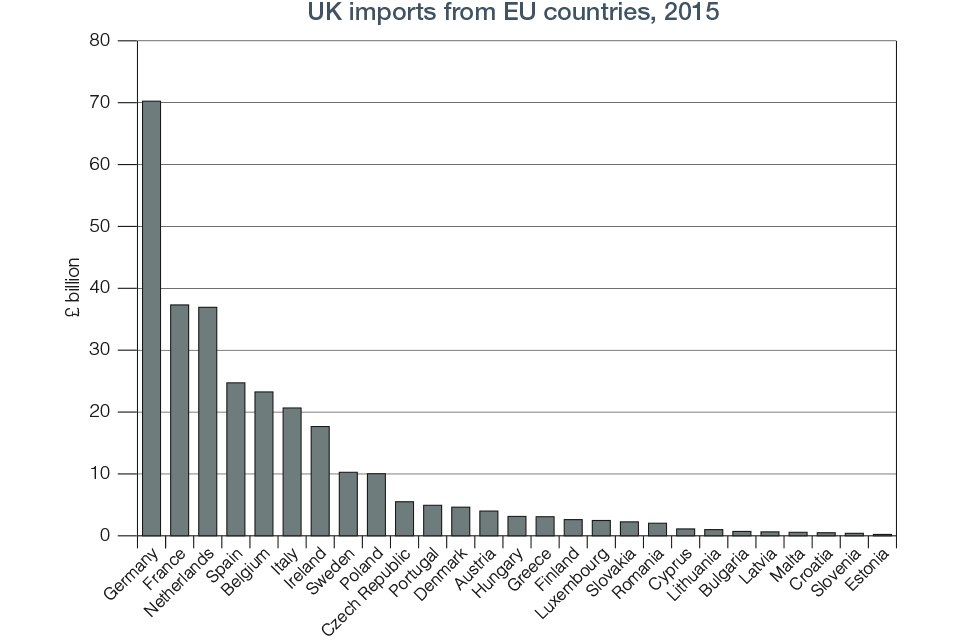

8.5 With the exception of trade with Ireland, the UK’s trade balance with other EU Member States is close to zero or negative. The UK imports more from the largest Member States than the UK exports to them. UK imports from Germany in 2015 were around £25 billion more than UK exports to Germany (Chart 8.1). UK imports from the Netherlands and France were each more than £37 billion, whilst UK imports from Italy, Belgium and Spain were each over £20 billion (Chart 8.2).[footnote 39]

Chart 8.1 – UK trade balance with EU countries

Source – ONS[footnote 40]

Chart 8.2 – UK imports from EU countries

Source – ONS[footnote 41]

8.6 Close trading relationships with the EU exist across a range of sectors. The UK is a major export market for important sectors of the EU economy, including in manufactured and other goods, such as automotives, energy, food and drink, chemicals, pharmaceuticals and agriculture. These sectors employ millions of people around Europe.

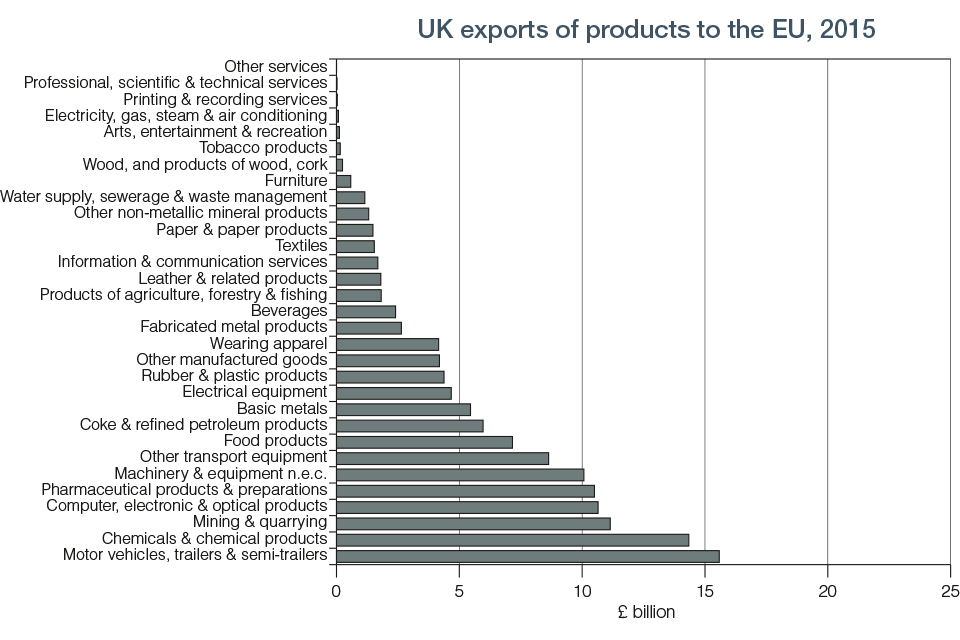

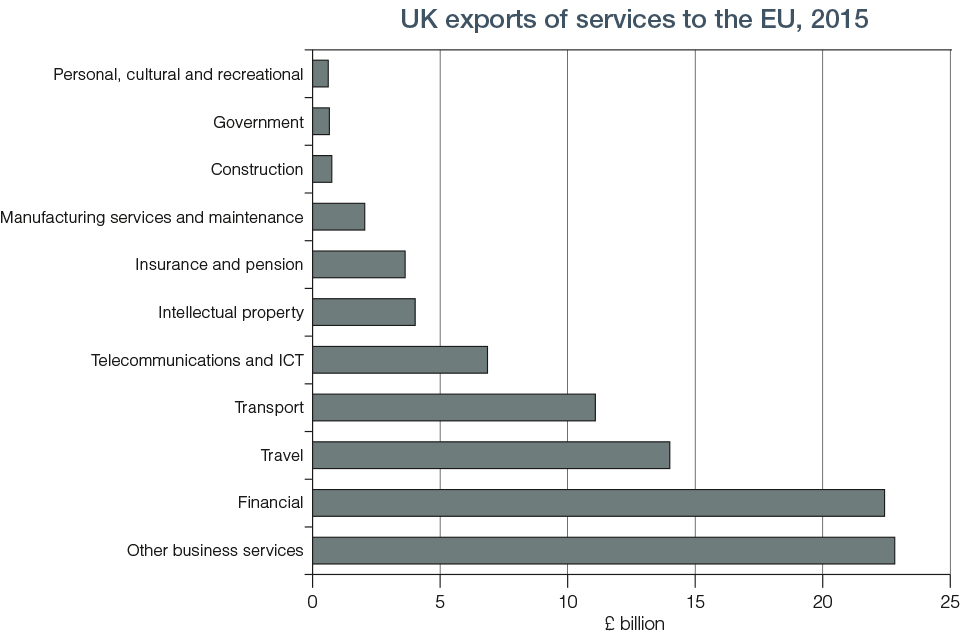

8.7 The UK exports a wide range of products and services to the EU. For example, exports of motor vehicles, chemicals and chemical products, financial services and other business services all account for significant shares of total UK exports to the EU.

Charts 8.3 and 8.4 – UK exports of products and services to the EU by sector[footnote 42]

Source – ONS[footnote 43]

Source – ONS[footnote 44]

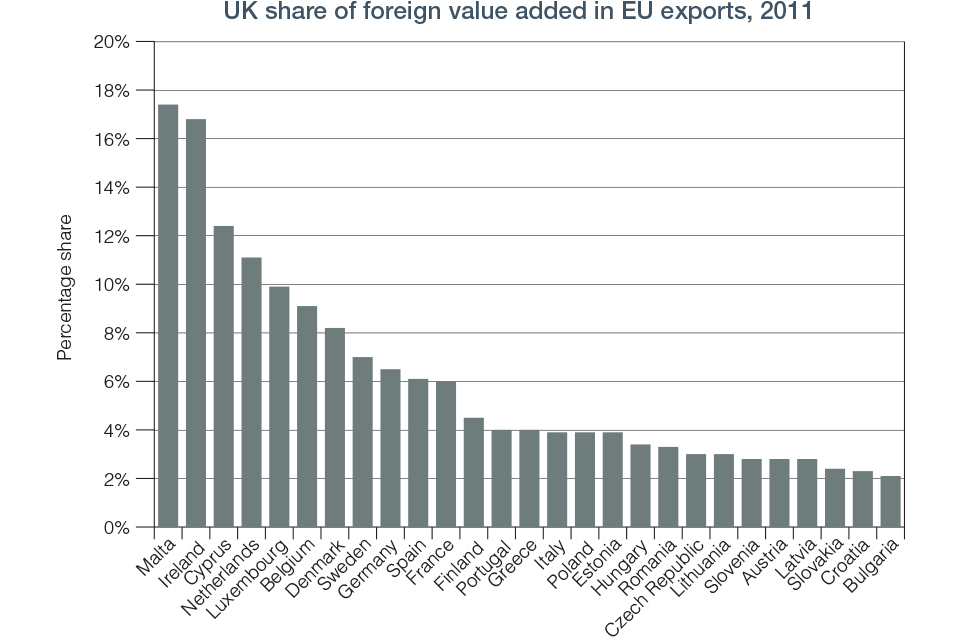

8.8 Producers in other EU Member States also rely on UK firms in their supply chains and vice versa. The integration of supply chains, which also benefits the UK, means that the UK often contributes a significant share of the foreign content in the EU countries’ exports. Chart 8.5 shows the UK share of foreign content in EU exports, which varies from two per cent for Bulgaria to over 17 per cent for Malta.[footnote 45]

8.9 This applies to services sectors, which are a growing component of global supply chains; and to many goods sectors, where parts and components move backwards and forwards across borders. For example, in Aerospace the wings for the Airbus A350 XWB are produced in the UK. The wings are made from many parts, drawing from expertise and excellence across the UK and EU. Although the wings are assembled in North Wales, they are designed and produced through cooperation between specialist teams in Germany, Spain, France and Filton, near Bristol.[footnote 46]

Chart 8.5 – UK share of foreign content in EU exports

Source – OECD[footnote 47]

8.10 We continue to supplement our analysis of trade data with a wide range of other analysis and engagement. We have structured our approach by five broad sectors covering the breadth of the UK economy: goods; agriculture, food and fisheries; services; financial services; and energy, transport and communications networks, as well as areas of crosscutting regulation. Within this, our stakeholder engagement and analysis covers over 50 specific sectors.

Goods

8.11 Free movement of goods within the EU is secured through a number of mechanisms, including through the principle of mutual recognition (which means that goods lawfully marketed in one Member State can be sold in all Member States), the harmonisation of product rules (where the same rules apply for a range of goods, such as for fertilisers, in all Member States) and agreement that manufacturers can use voluntary standards as a way of demonstrating compliance with certain essential characteristics set out in EU law (such as for toy safety). In a number of sectors covering typically higher risk goods (such as chemicals or medicines), the EU has also agreed more in-depth harmonised regulatory regimes, including for testing or licensing.

Standards

Standards are voluntary technical agreements about the best way to do something, such as how to manufacture a certain product. They are developed by industry and other stakeholders through processes that seek consensus. The majority of standards have been developed for purely commercial reasons to support the interoperability of firms and international trade.

Over time, standards have been increasingly developed at a global level, through the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). These international standards are then adopted at regional, including European, and national levels. The British Standards Institution (BSI) will retain its membership of these organisations after exit and we expect the UK to continue to play a leading role in driving the development of global standards.

The European Standards Organisations are not EU bodies, though they have a special status in the EU. Approximately 25 per cent of published European standards have, in part, and whilst still voluntary, been developed by the European Standards Organisations as a result of requests from the European Commission.[footnote 48] This subset of standards provides businesses with a way of demonstrating compliance with EU product laws, such as with respect to gas appliance rules.

We are working with BSI to ensure that our future relationship with the European Standards Organisations continues to support a productive, open and competitive business environment in the UK.

8.12 In many cases EU rules are based on global requirements. For example, the UN Economic Commission for Europe sets global vehicle safety standards. As part of our vision for an outward-facing global UK we will continue to play a leading role in such international fora.

8.13 Our new partnership should allow for tariff-free trade in goods that is as frictionless as possible between the UK and the EU Member States.

Agriculture, food and fisheries

8.14 The UK’s agriculture, food and fisheries sectors are currently heavily influenced by EU laws, through frameworks such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Common Fisheries Policy, and through other rules meeting multiple objectives, such as high levels of environmental protection or animal welfare.

8.15 With respect to agriculture and food, the UK is a net importer of agri-food goods. Whilst UK exports of agriculture, fisheries and food products to the EU were £11 billion in 2015, imports were £28 billion and over 70 per cent of our annual agri-food imports come from the EU.[footnote 49] This underlines the UK and EU’s mutual interest in ensuring continued high levels of market access in future. In addition, and with EU spend on CAP at around €58 billion in 2014 (nearly 40 per cent of the EU’s budget),[footnote 50] leaving the EU offers the UK a significant opportunity to design new, better and more efficient policies for delivering sustainable and productive farming, land management and rural communities. This will enable us to deliver our vision for a world-leading food and farming industry and a cleaner, healthier environment, benefiting people and the economy.

8.16 In 2015, EU vessels caught 683,000 tonnes (£484 million revenue) in UK waters and UK vessels caught 111,000 tonnes (£114 million revenue) in Member States’ waters.[footnote 51] Given the heavy reliance on UK waters of the EU fishing industry and the importance of EU waters to the UK, it is in both our interests to reach a mutually beneficial deal that works for the UK and the EU’s fishing communities. Following EU exit, we will want to ensure a sustainable and profitable seafood sector and deliver a cleaner, healthier and more productive marine environment.

Services (excluding Financial Services)

8.17 The services sector is large and diverse, including areas such as retail, accountancy, consulting, legal services, business services, creative industries – like film, TV, design, music and fashion – medical services, tourism and catering.

Integration of services sectors with the rest of the economy

Services sectors are a large and export-rich part of the UK economy and an important and growing integrated component of value chains. For example, services inputs represented 37 per cent of the total value of UK exports of manufactured goods in 2011.[footnote 52]

Firms increasingly use logistics, communications services and business services to facilitate the effective functioning of their supply chains. In particular, the professional and business services sector provides valuable consultancy and administrative services to a range of sectors including financial services.

8.18 The Single Market for services is not complete. It seeks to remove barriers to businesses wanting to provide services across borders, or to establish a company in another EU Member State, through a range of horizontal and sector-specific legislation. This includes the mutual recognition of professional qualifications. The EU’s Digital Single Market measures are designed to ensure the regulatory environment keeps pace with the evolving digital economy.

8.19 We recognise that an effective system of civil judicial cooperation will provide certainty and protection for citizens and businesses of a stronger global UK.

8.20 The EU is a party to negotiations on the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) with more than twenty other countries. The UK continues to be committed to an ambitious TiSA and will play a positive role throughout the negotiations.

8.21 In our new strategic partnership we will be aiming for the freest possible trade in services between the UK and EU Member States.

Financial Services

8.22 The financial services sector is an important part of our economy. It is not just a London-based sector; for example, two thirds of financial and related professional services[footnote 53] jobs are based outside the capital, including 156,700 in Scotland, 54,300 in Wales and 32,000 in Northern Ireland.[footnote 54] The UK is a global leader in a range of activities, including complex insurance, wholesale markets and investment banking, the provision of market infrastructure, asset management and FinTech.

8.23 There are a range of provisions across many different pieces of EU financial regulation, which allow firms in Member States to provide financial services across the EU under a common set of rules and a single authorisation from their regulator – these are often referred to as financial services passports. Both UK and EU firms benefit from these arrangements – there are over 5,000 UK firms that utilise passports to provide services across the rest of the EU, but around 8,000 European firms that use passports to provide services into the UK.[footnote 55]

8.24 Additionally, there are provisions that allow firms from ‘third countries’ to provide services across the EU, provided that their relevant domestic regulations have been deemed equivalent to those of the EU.

8.25 In our new strategic partnership agreement we will be aiming for the freest possible trade in financial services between the UK and EU Member States.

8.26 In highly integrated sectors such as financial services there will be a legitimate interest in mutual cooperation arrangements that recognise the interconnectedness of markets, as so clearly demonstrated by the financial crisis. Since that time, the EU has taken a number of steps to strengthen collective oversight of the sector. As the UK leaves the EU, we will seek to establish strong cooperative oversight arrangements with the EU and will continue to support and implement international standards to continue to safely serve the UK, European and global economy.

A European global financial centre

The financial services sector is an important part of the European economy, contributing significantly to the funding and growth of European business. It is in the interests of the UK and the EU that this should continue in order to avoid market fragmentation and the possible disruption or withdrawal of services.

The UK’s financial services sector is a hub for money, trading and investment from all over the world and is one of only two global, full service financial centres – and the only one in Europe. In 2016 the Global Financial Centres Index once again ranked London as the number one financial centre.[footnote 56]

Citizens, businesses and public sector bodies across the continent rely on the City to access the services that they need. Over 75 per cent of the EU27’s capital market business is conducted through the UK.[footnote 57] The UK industry manages £1.2 trillion of pension and other assets on behalf of European clients.[footnote 58] The UK is also responsible for 37 per cent of all European Initial Public Offerings, while the UK receives more than one-third of all venture capital invested in the EU.[footnote 59]

EU27 firms also have an interest in continuing to serve UK customers.

The fundamental strengths that underpin the UK financial services sector, such as our legal system, language and our world-class infrastructure will help to ensure that the UK remains a pre-eminent global financial centre.

Energy, transport and communications networks

8.27 There are three UK-wide network industries and associated services which interact extensively with the EU: transport, energy and communications. All three are important in their own right and are key ‘enablers’ to the functioning and success of the economy as a whole.

8.28 With respect to energy, EU legislation underpins the coordinated trading of gas and electricity through existing interconnectors with Member States, including Ireland, France, Belgium and the Netherlands. There are also plans for further electricity interconnections between the UK and EU Member States and EEA Members. These coordinated energy trading arrangements help to ensure lower prices and improved security of supply for both the UK and EU Member States by improving the efficiency and reliability of interconnector flows, reducing the need for domestic back-up power and helping balance power flows as we increase the level of intermittent renewable electricity generation. We are considering all options for the UK’s future relationship with the EU on energy, in particular, to avoid disruption to the all-Ireland single electricity market operating across the island of Ireland, on which both Northern Ireland and Ireland rely for affordable, sustainable and secure electricity supplies.

8.29 The Euratom Treaty provides the legal framework for civil nuclear power generation and radioactive waste management for members of the Euratom Community, all of whom are EU Member States. This includes arrangements for nuclear safeguards, safety and the movement and trade of nuclear materials both between Euratom Members such as France and the UK, as well as between Euratom Members and third countries such as the US.

8.30 When we invoke Article 50, we will be leaving Euratom as well as the EU. Although Euratom was established in a treaty separate to EU agreements and treaties, it uses the same institutions as the EU including the Commission, Council of Ministers and the Court of Justice.[footnote 60] The European Union (Amendment) Act 2008 makes clear that, in UK law, references to the EU include Euratom. The Euratom Treaty imports Article 50 into its provisions.

8.31 As the Prime Minister has said, we want to collaborate with our EU partners on matters relating to science and research, and nuclear energy is a key part of this. So our precise relationship with Euratom, and the means by which we cooperate on nuclear matters, will be a matter for the negotiations – but it is an important priority for us – the nuclear industry remains of key strategic importance to the UK and leaving Euratom does not affect our clear aim of seeking to maintain close and effective arrangements for civil nuclear cooperation, safeguards, safety and trade with Europe and our international partners. Furthermore, the UK is a world leader in nuclear research and development and there is no intention to reduce our ambition in this important area. The UK fully recognises the importance of international collaboration in nuclear research and development and we will ensure this continues by seeking alternative arrangements.

8.32 In the transport sector, there is a substantial body of EU law covering four transport modes (aviation, roads, rail and maritime), which governs our current relationship with the EU, and which will need to be taken into consideration as we negotiate our future relationship. For example, in aviation, the standard international arrangement is that air services operate under rights granted through bilateral air services agreements between nation states. In the late 1980s and early 1990s the EU created an internal aviation market whereby any carrier licensed in the EU is entitled to operate any service in the EU, superseding the old bilateral arrangements. As we exit the EU, there will be a clear interest for all sides to seek arrangements that continue to support affordable and accessible air transport for all European citizens, as well as maintaining and developing connectivity. We will also seek to agree bilateral air services agreements with countries like the US, where our air services arrangements are currently covered by an agreement between the EU and the US.

8.33 Similar issues are raised with respect to Road Haulage, where it is the EU’s regulatory framework that guarantees rights for HGV operators to carry goods to, from, through and within other EU countries. Around 99 per cent of total international road freight for the UK is to and from the other EU27 nations. Approximately 80 per cent of this cross-border haulage is handled by foreign hauliers.[footnote 61], [footnote 62]

8.34 With respect to communications networks, telecoms operators are regulated in the UK by the EU’s ‘Electronic Communications Framework’, which promotes competition and choice. As we exit the EU, we will want to ensure that UK telecoms companies can continue to trade as freely and competitively as possible with the EU and let European companies do the same in the UK.

8.35 Content that is carried over electronic communication networks is regulated in the EU by the Audiovisual Media Services Directive. This underpins the operation of the internal market for broadcasting by ensuring the freedom to provide broadcasting services throughout the EU. The UK is currently the EU’s biggest broadcasting hub, hosting a large number of international broadcasting companies. In the course of the negotiations, we will focus on ensuring the ability to trade as freely as possible with the EU and supporting the continued growth of the UK’s broadcasting sector.

Cross-cutting regulations

8.36 A range of cross-cutting regulations underpin the provision and high standards of goods and services, maintaining a positive environment for businesses, investors and consumers. For example, a common competition and consumer protection framework deals with mergers, monopolies and anti-competitive activity and unfair trading within the EU on a consistent basis, and EU-wide systems facilitate the protection of intellectual property.

8.37 As we leave the EU, the Government is committed to making the UK the best place in the world to do business. This will mean fostering a high quality, stable and predictable regulatory environment, whilst also actively taking opportunities to reduce the cost of unnecessary regulation and to support innovative business models.

8.38 The stability of data transfer is important for many sectors – from financial services, to tech, to energy companies. EU rules support data flows amongst Member States. For example, the EU data protection framework outlines the rights of EU citizens, as well as the obligations to which companies must adhere when processing and transferring this data. There is also an ongoing consultation regarding the free flow of data, including considering whether legislation is necessary to limit Member States’ requirements for data to be stored nationally.

8.39 The European Commission is able to recognise data protection standards in third countries as being essentially equivalent to those in the EU, meaning that EU companies are able to transfer data to those countries freely.

8.40 As we leave the EU, we will seek to maintain the stability of data transfer between EU Member States and the UK.

8.41 The Government is committed to ensuring we become the first generation to leave the environment in a better state than we found it. We will use the Great Repeal Bill to bring the current framework of environmental regulation into UK and devolved law. The UK’s climate action will continue to be underpinned by our climate targets as set out in the Climate Change Act 2008 and through our system of five-yearly carbon budgets, which in turn support our international work to drive climate ambition. We want to take this opportunity to develop over time a comprehensive approach to improving our environment in a way that is fit for our specific needs.

European Union agencies

8.42 There are a number of EU agencies, such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European (Financial Services) Supervisory Authorities (ESAs), which have been established to support EU Member States and their citizens. These can be responsible for enforcing particular regulatory regimes, or for pooling knowledge and information sharing. As part of exit negotiations the Government will discuss with the EU and Member States our future status and arrangements with regard to these agencies.

A mutually beneficial new customs arrangement

8.43 After we have left the EU, we want to ensure that we can take advantage of the opportunity to negotiate our own preferential trade agreements around the world. We will not be bound by the EU’s Common External Tariff or participate in the Common Commercial Policy. But we do want to ensure that cross-border trade with the EU is as frictionless and seamless as possible. These are our guiding objectives for the future customs arrangements with the EU.

8.44 The UK is currently a member of the EU’s Customs Union. As we look to build our future customs relationship with the EU and the rest of the world, we start from a strong position. As a large trading nation, we possess a world-class customs system which handles imports and exports from all over the world. We already have highly efficient processes for freight arriving from the rest of the world – the vast majority of customs declarations in the UK are submitted electronically and are cleared rapidly. Only a small proportion cannot go through so rapidly, for instance where risk assessment indicates that compliance and enforcement checks are required at the border. The World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index shows that HMRC operates one of the world’s most efficient customs regimes.[footnote 63]

The EU Customs Union

A customs union is an arrangement between two or more countries designed to allow goods to circulate freely within the area of the customs union, by the introduction of a common external tariff for its members and the removal of tariffs between them. It does not cover trade in services or free movement of capital or people.

A customs union facilitates the movement of goods between its members. However the requirement to have a common external tariff, applied equally by all members, by its nature restricts members’ ability to enter into separate free trade agreements (FTAs) with third countries, by preventing members from applying a different tariff to the common external tariff.

The EU Customs Union is a deep model, which comprises the 28 EU Member States. Turkey, San Marino and Andorra also have their own customs unions with the EU.[footnote 64] The Overseas Territories of the UK (with the exception of Gibraltar and the Sovereign Base Areas on Cyprus) are not part of the EU, nor are they in the EU Customs Union. EU law applies to a large extent to Gibraltar, but it is not in the EU Customs Union.[footnote 65] The UK’s Sovereign Base Areas on Cyprus, together with Monaco, are considered to be part of the Customs Union.[footnote 66] The Crown Dependencies are not in the EU,[footnote 67] but are in the EU Customs Union.[footnote 68]

Goods in the EU Customs Union move freely without tariffs, quotas or routine customs controls. Tariffs, quotas and customs controls for goods moving between the EU and non-EU countries are determined at EU, rather than national, level.

Under the EU Customs Union, customs policy is the exclusive competence of the EU. All EU Member States are required to operate customs procedures in accordance with EU legislation (the ‘Union Customs Code’). The UK decides which government department or agency is responsible for implementing and enforcing customs law in the UK. Within the last decade, the UK has seen various customs functions performed by HM Revenue and Customs, the UK Border Agency and Border Force. Currently customs functions are performed by HM Revenue and Customs and Border Force.

Services are not directly included in a customs union (they are subject to neither tariffs nor customs controls) but have become increasingly embedded in goods production. So a customs union could indirectly affect trade in services industries, for example, in parallel to exporting cars, an automotive firm might also provide financial services.

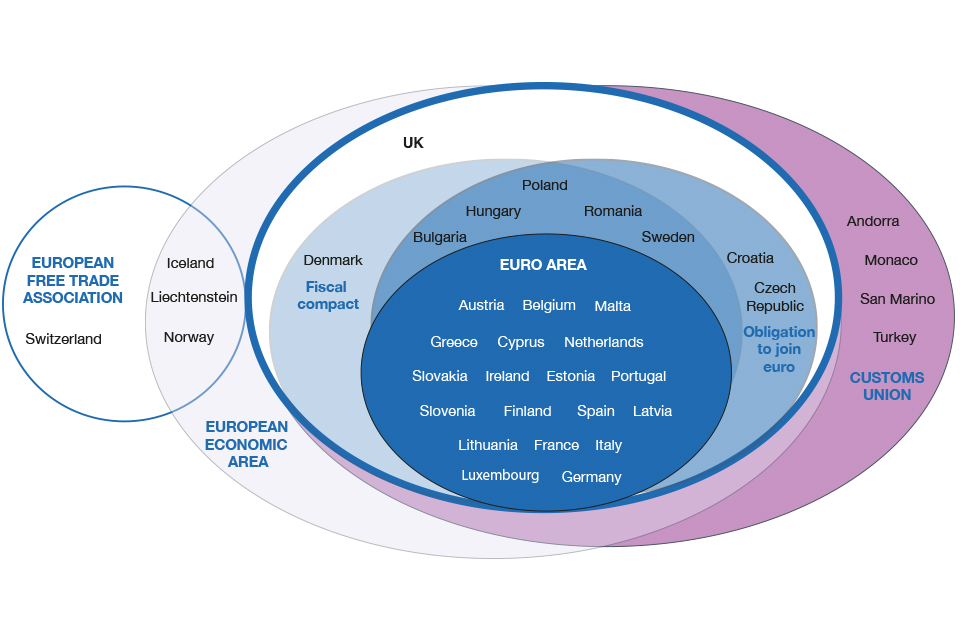

EU and related membership groupings

The diagram below shows which countries are members of the various groupings associated with the EU. As set out above, all EU Member States are in the EU Customs Union. A number of additional countries also have a customs union arrangement with the EU, such as Turkey.

8.45 In leaving the EU, the UK will seek a new customs arrangement with the EU, which enables us to make the most of the opportunities from trade with others and for trade between the UK and the EU to continue to be as frictionless as possible. There are a number of options for any new customs arrangement, including a completely new agreement, or for the UK to remain a signatory to some of the elements of the existing arrangements. The precise form of this new agreement will be the subject of negotiation.

8.46 It is in the interests of both the UK and the EU to have a mutually beneficial customs arrangement to ensure goods trade between the UK and EU can continue as much as possible as it does now. This will form a key part of our ambition for a new strategic partnership with the EU.

8.47 Whatever form that customs arrangement takes, and whatever the mechanism to deliver it, we will seek to maintain many of the facilitations that businesses currently enjoy, whilst aiming that, if there are requirements for customs procedures, these are as frictionless as possible. Whilst we will look at precedents set by customs agreements between other countries, we will not seek to replicate another country’s model and will pursue the best possible deal for the UK.