HM Government transparency report: disruptive powers 2018 to 2019 (accessible version)

Published 19 March 2020

HM Government Transparency Report: Disruptive Powers 2018/19

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for the Home Department by Command of Her Majesty

March 2020

CP212

1. Foreword

The threat posed by serious crime, terrorism and hostile state activity is becoming increasingly complex. The horrific attacks at Fishmongers’ Hall last November 2019, and in Streatham earlier this year, are a shocking reminder of the challenges we continue to face.

In January, the Government announced a raft of measures to strengthen the UK’s response to terrorism. These measures included a new Counter-Terrorism (Sentencing and Release) Bill to ensure tougher sentences and longer licence periods for terrorist offenders; a doubling of the number of CT specialist probation staff; an independent review of Multi Agency Public Protection Arrangements (MAPPA) being led by Jonathan Hall QC; and funding for counter- terrorism policing increasing to £906m in 2020/21, a £90m year-on-year increase.

The Government also introduced emergency legislation last month to ensure an end to terrorist offenders getting released early automatically and that anyone released before the end of their sentence will be dependent on a risk assessment by the Parole Board. On 26 February, the Terrorist Offenders (Restriction of Early Release) Act 2020 received Royal Assent. Its provisions, which came into force with immediate effect, mean that around 50 terrorist prisoners already serving affected sentences will see their automatic release halted.

Of course, we must not lose sight of what we are striving to achieve: a democratic, safe and secure society underpinned by fundamental values like tolerance and respect for the rule of law. This is what sets us apart from our adversaries. Therefore, we take great steps to ensure the powers described in this report are used only when it is necessary and proportionate. While much of the work undertaken to protect our national security necessarily goes unseen, we remain as committed as ever to being as transparent as possible about how these powers are used. This report is part of that commitment.

This is the fourth edition of this report and, as was the case in the previous iterations, it brings together and seeks to explain information, both in relation to the threats we face and the various disruptive powers used to counter them.

Through this process, we seek to provide a comprehensive understanding of the tools that are available to our dedicated law enforcement and security and intelligence agencies, and the essential part those tools play in protecting the public and defending our national security.

Priti Patel Home Secretary

2. Introduction

The first priority of any Government is keeping the United Kingdom safe and secure.

Under the Government’s counter-terrorism strategy CONTEST, we work to reduce the risk to the UK and its interests overseas from terrorism, so that people can go about their lives freely and with confidence. Drawing on lessons learned from the attacks in London and Manchester in 2017, an updated and strengthened CONTEST was published in June of 2018.

The UK is facing a number of different and enduring terrorist threats. Despite their loss of geographic territory, Daesh retain their ability to inspire and direct attacks across the world, while Al Qa’ida remains a persistent threat. Extreme right wing terrorism is increasing, as the heinous attacks in Christchurch and El Paso show. And, there continues to be an ongoing threat from Northern Ireland Related Terrorism.

Serious and organised crime (SOC) is an inherently transnational security threat and evolves at pace. Its impact is wide-ranging, continuous and cumulatively damaging. Serious and organised criminals target vulnerable individuals, public services and the private sector. The resulting harm to the economy, communities and citizens is extensive; SOC affects more UK citizens, more often, than any other national security threat and leads to more deaths in the UK each year than all other national security threats combined.

To counter these and other threats, it is crucial that we have the necessary powers and that they are used appropriately and proportionately.

This report includes figures on the use of disruptive and investigative powers. It explains their utility and outlines the legal frameworks that ensure they can only be used when necessary and proportionate, in accordance with the statutory functions of the relevant public authorities.

There are limitations concerning how much can be said publicly about the use of certain sensitive techniques. To go into too much detail may encourage criminals and terrorists to change their behaviour in order to evade detection.

However, it is extremely important that the public are confident that the security and intelligence and law enforcement agencies have the powers they need to protect the public and that these powers are used proportionately. The agencies rely on many members of the public to provide support to their work. If the public do not trust the police and security and intelligence agencies, that mistrust would result in a significant operational impact.

The purpose of this report is therefore to provide the public with a complete guide, in one place, of the powers used to combat threats to the security of the United Kingdom, the extent of their use and the safeguards and oversight in place to protect against their misuse.

Unlike previous iterations of this report, material that is now consolidated into the Investigatory Powers Commissioners (IPC) report is not included. The first IPC report was published on 31 January 2019. The IPC report covers statistical information on the use of investigatory powers and an account of the oversight work of IPC and predecessor organisations of the use of investigatory powers.

This is the first report to include statistics on MI5 investigations and Closed SOIs (Subjects of Interest).

3. Terrorism Arrests and Outcomes

Conviction in a court is one of the most effective tools we have to stop terrorists. The Government is therefore committed to pursuing convictions for terrorist offences where they have occurred. Terrorism-related arrests are made under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE). They can also be made under the Terrorism Act 2000 (TACT) in circumstances where arresting officers require additional powers of detention or need to arrest a person suspected of terrorism-related activity without a warrant. Whether to arrest someone under PACE or TACT is an operational decision to be made by the police.

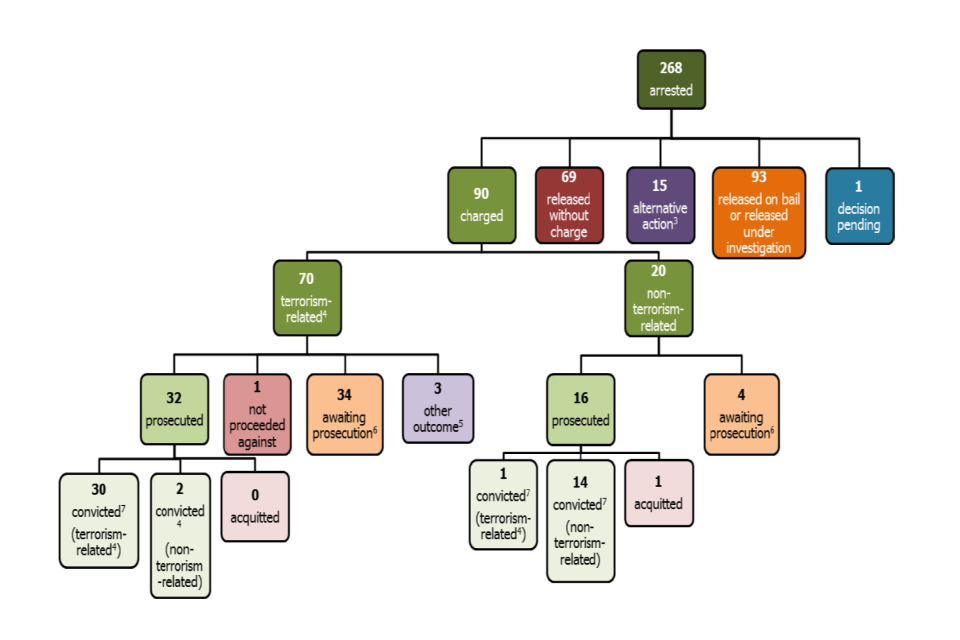

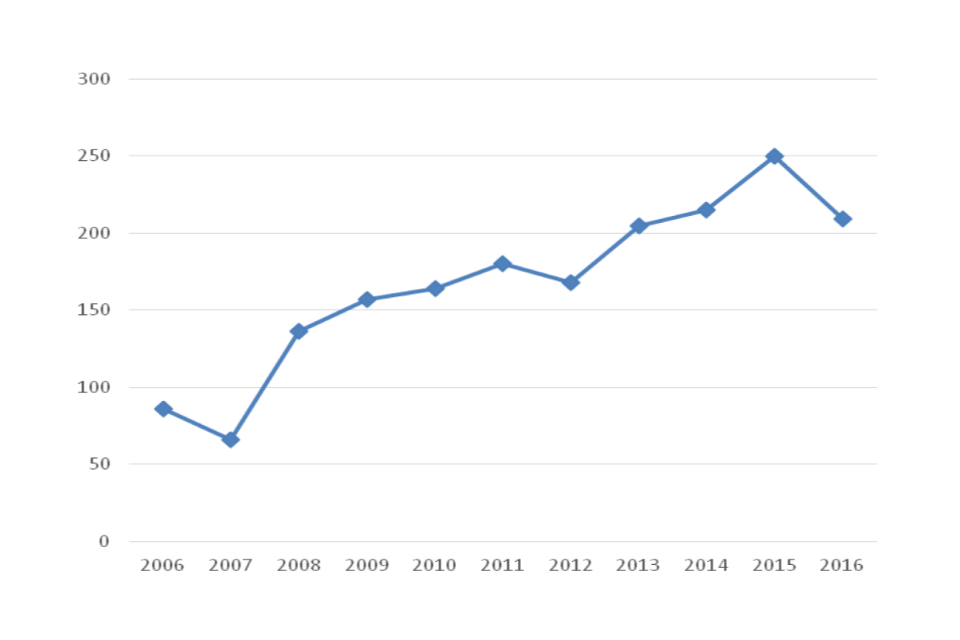

In the year ending 31 March 2019, 268 persons were arrested for terrorism-related activity, a decrease of 40% from the 443 arrests in the previous year. This was the lowest number of arrests in a year since the year ending March 2014.

Of the 268 arrests, 90 (34%) resulted in a charge, and of those charged, 70 were considered to be terrorism-related. Many of these cases are ongoing, so the number of charges resulting from the 268 arrests in the year ending 31 March 2019 can be expected to rise over time.

Of the 70 people charged with terrorism-related offences, 32 have been prosecuted and 34 are awaiting prosecution. All 32 of the prosecution cases led to individuals being convicted of an offence: 30 for terrorism-related offences and two for non-terrorism related offences.

As at 31 March 2019, there were 223 persons in custody in Great Britain[footnote 1] for terrorism-related offences. This total was comprised of 178 persons (80%) in custody who held Islamist-extremist views, 33 (15%) who held far right-wing ideologies and a further 12 other persons. This was an increase of 5 persons compared to the 228 persons in custody as at 31 March 2018. The number of individuals in custody for terrorism-related offences has shown a steady increase in recent years, across all ideologies.

Terrorism arrests and outcomes are often highly reliant on the investigatory powers and tools outlined in this report.

Figure 1: Arrests and outcomes year ending 31 March 2019

The flow chart is designed to summarise how individuals who are arrested on suspicion of terrorism-related activity are dealt with through the criminal justice system. It follows the process from the point of arrest, through to charge (or other outcomes) and prosecution.

Source: Home Office, ‘Operation of police powers under the Terrorism Act 2000 and subsequent legislation’, data tables A.01 to A.07

Flow Chart Notes:

- Based on time of arrest.

- Data presented are based on the latest position with each case as at the date of data provision from National Counter Terrorism Police Operations Centre (NCTPOC) (23 April 2019).

- ‘Alternative action’ includes a number of outcomes, such as cautions, detentions under international arrest warrant, transfer to immigration authorities etc. See table https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/operation-of-police-powers-under-the-terrorism-act-2000-financial-year-ending-march-2019 for a complete list.

- Terrorism-related charges and convictions include some charges and convictions under non-terrorism legislation, where the offence is considered to be terrorism-related.

- The ‘other’ category includes other cases/outcomes such as cautions, transfers to Immigration Enforcement Agencies, the offender’s details being circulated as wanted, and extraditions.

- Cases that are ‘awaiting prosecution’ are not yet complete. As time passes, these cases will eventually lead to a prosecution, ‘other’ outcome, or it may be decided that the individual will not be proceeded against.

- Excludes convictions that were later quashed on appeal.

4. Serious Organised Crime Arrests and Outcomes

The National Crime Agency (NCA) is responsible for leading and coordinating the fight against serious and organised crime affecting the UK.

The NCA published its latest Annual Report and Accounts on 22 July 2019[footnote 2]. This report explains the NCA’s response to the threat we face from serious and organised crime between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2019. An outline of this activity is below.

It should be noted that these figures provide only an indication of the response to serious and organised crime. The NCA is focused on the disruptive impact of its activities against priority threats and high priority criminals and vulnerabilities, rather than simply numbers of arrests or volumes of seizures. Furthermore, the UK’s overall effort to tackle serious and organised crime also involves a wide range of other public authorities, including police forces, Immigration Enforcement, Border Force and HM Revenue and Customs.

Arrests and Convictions

A significant part of the NCA’s activity to disrupt serious and organised crime is to investigate those responsible in order that they can be prosecuted. In the period from 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019, 731 individuals were arrested in the UK by NCA officers, or by law enforcement partners working on NCA-tasked operations and projects. In the same period, there were 375 convictions in relation to NCA casework in the UK and 1,723 disruptions. NCA activity also contributed to 618 arrests overseas. Disruptions, in this context, refers to the impact of law enforcement activity against serious organised crime.

Interdictions

Between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2019, activity by the NCA resulted in the interdiction of over 130 tonnes of drugs, including 76.4 tonnes of cocaine and 0.8 tonnes of heroin. In addition, during this period NCA activity resulted in the seizure of 174 guns and 26 other firearms.

Criminal Finances

In the period from 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 the NCA recovered assets worth £20.5 million. In addition, the agency denied assets of £53.4 million. Asset denial activity included cash seizures, restrained assets and frozen assets.

Child Protection

In this reporting period, NCA activity led to 2,721 children being protected or safeguarded. Child protection is when action is taken to ensure the safety of a child, such as taking them out of a harmful environment. Child safeguarding is a broader term including working with children in their current environment, such as working with a school or referring a child for counselling. As with terrorism arrests and convictions, serious and organised crime outcomes such as those outlined above are often highly reliant on the investigative powers outlined in this report.

5. Disruptive Powers

5.1 Stops and Searches

Powers of search and seizure are vital in ensuring that the police are able to acquire evidence in the course of a criminal investigation and are powerful disruptive tools in the prevention of terrorism.

Section 47A of the Terrorism Act 2000 (TACT) enables a senior police officer to give an authorisation, specifying an area or place where they reasonably suspect that an act of terrorism will take place. Within that area and for the duration of the authorisation, a uniformed police constable may stop and search any vehicle or person for the purpose of discovering any evidence – whether or not they have a reasonable suspicion that such evidence exists – that the person is or has been concerned in the commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism, or that the vehicle is being used for such purposes.

The authorisation must be necessary to prevent the act of terrorism which the authorising officer reasonably suspects will occur, and it must specify the minimum area and time period considered necessary to do so. The authorising officer must inform the Secretary of State of the authorisation as soon as is practicable, and the Secretary of State must confirm it. If the Secretary of State does not confirm the authorisation, it will expire 48 hours after being made. The Secretary of State may also substitute a shorter period, or a smaller geographical area, than was specified in the original authorisation.

Until September 2017, this power had not been used in Great Britain since the threshold of authorisation was formally raised in 2011. This reflects the intention that the power should be reserved for exceptional circumstances, and the requirement that it only be used where necessary to prevent an act of terrorism that it is reasonably suspected is going to take place within a specified area and period. However, following the Parsons Green attack, on 15 September 2017, the power was authorised for the first time, by four forces: British Transport Police (BTP), City of London Police, North Yorkshire Police and West Yorkshire Police. There were a total of 128 stop and searches conducted (126 of which were conducted by BTP), which resulted in 4 arrests (all BTP).

In the year ending 31 March 2019, 685 persons were stopped and searched by the Metropolitan Police Service under section 43 of TACT (this data is not available in relation to other police forces). This represents a 15% decrease from the previous year’s total of 808. However, over the longer term, there has been a 44% fall in the number of stop and searches, from 1,229 in the year ending 31 March 2010 (the first comparator year that figures are available for). In the year ending 31 March 2019, there were 70 resultant arrests; the arrest rate of those stopped and searched under section 43 was 10%, up from 8% in the previous year.[footnote 3]

5.2 Port and Border Controls

Schedule 7 to the Terrorism Act 2000 (Schedule 7) helps protect the public by allowing an examining police officer to stop and question and, when necessary, detain and search individuals travelling through ports, airports, international rail stations or the border area. The purpose of the questioning is to determine whether that person appears to be someone who is, or has been, involved in the commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism. The Schedule 7 power also extends to examining goods to determine whether they have been used in the commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism.

Prior knowledge or suspicion that someone is involved in terrorism is not required for the exercise of the Schedule 7 power. Examinations are also about talking to people in respect of whom there is no suspicion but who, for example, are travelling to and from places where terrorist activity is taking place, to determine whether those individuals are, or have been, involved in terrorism.

The Schedule 7 Code of Practice for examining officers provides guidance on the selection of individuals for examination. The most recent version of the Code, which came into effect on 25 March 2015[footnote 4], is clear that selection of a person for examination must not be arbitrary or for discriminatory reasons and so should not be based on protected characteristics alone. When deciding whether to select a person for examination, officers will take into account considerations that relate to the threat of terrorism, including known and suspected sources of terrorism, specific patterns of travel and observation of a person’s behaviour.

When an individual is examined under Schedule 7 they are given a Public Information Leaflet, which is available in multiple languages and outlines the purpose of Schedule 7 as well as any rights and obligations relating to use of the powers. No person can be examined for longer than an hour unless the examining officer has formally detained them. Any person detained under Schedule 7 powers is entitled to receive legal advice from a solicitor and have a named person informed of their detention. A more senior ‘review officer’ who is not directly involved in the questioning of the individual must then consider on a periodic basis whether the continued detention is necessary.

The Public Information Leaflet and Code of Practice also include relevant contact details in case a person wishes to make a complaint regarding their examination. An individual can complain about a Schedule 7 examination by writing to the Chief Officer of the police force for the area in which the examination took place. Additionally, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation is responsible for reporting each year on the operation of the Schedule 7 power.

Statistics on the operation of Schedule 7 powers are published by the Home Office on a quarterly basis[footnote 5]. In the year ending 31 March 2019, a total of 11,154 persons were examined under this power in Great Britain, a fall of 28% on the previous year. Throughout the same period, the number of detentions following examinations increased by 3% from 1,776 in the year ending 31 March 2018 to 1,832 in the year ending 31 March 2019.

Of those individuals that were detained (excluding those who did not state their ethnicity), 30% categorised themselves as ‘Asian or Asian British’. The next most prominent ethnic groups were ‘Chinese or other’ at 28% and ‘White’ at 12%. The proportion of those that categorised their ethnicity as ‘Black or Black British’ or ‘Mixed’ made up 10% and 7% respectively.

Use of Schedule 7 is informed by the current terrorist threat to the UK and intelligence underpinning the threat assessment. Self-defined members of ethnic minority communities do comprise a majority of those examined under Schedule 7. However, the proportion of those examined should correlate not to the ethnic breakdown of the general population, or even the travelling population, but to the ethnic breakdown of the terrorist population. In successive reports the former Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, David Anderson QC, declared that he had no reason to believe that Schedule 7 powers are exercised in a racially discriminatory way. Indeed, the most recent former Reviewer, Max Hill QC, did not depart from this position, suggesting it is not as simple as assertions put forward by some critics that the powers are being used in a discriminatory way against certain ethnicities.

Since April 2016, the Home Office has collected additional data relating to the use of Schedule 7 powers. This data includes the number of goods examinations (sea and air freight), the number of strip searches conducted, and the number of refusals following a request by an individual to postpone questioning. In the year ending 31 March 2019, a total of 1,590 air freight and 4,159 sea freight examinations were conducted in Great Britain. Regarding strip searches over the same period, there were three instances carried out under Schedule 7. Postponement of questioning (usually to enable an individual to consult a solicitor) was refused on three occasions.

5.3 Terrorist Asset-Freezing

Terrorist asset-freezing is an important disruptive tool, which aims to stop terrorist acts by preventing funds, economic resources or financial services from being made available to, or used by, someone who might use them for terrorist purposes. The power to freeze assets does not require a criminal prosecution. The UK currently imposes an asset freeze against individuals and entities under UK, EU and/or United Nations sanctions regimes.

The UK’s autonomous asset-freezing regime (set out in the Terrorist Asset-Freezing etc. Act 2010 - “TAFA”)[footnote 6] meets obligations placed on the UK by UN Security Council Resolutions and associated European Union legislation. Meeting these obligations is, in turn, also part of the 40 standards on anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing set out by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). FATF evaluated the UK’s compliance with its standards in 2018 and has given the UK the highest possible ratings on the UK’s system to combat terrorist financing. The full report can be found here: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer4/MER-United-Kingdom-2018.pdf.

TAFA gives the UK Treasury the power to impose financial restrictions on individuals and entities. These restrictions have the effect of freezing any funds or economic resources owned, held, or controlled by a designated person or entity. They also make it an offence for any person to make funds, financial services or economic resources available (directly or indirectly) to, or for the benefit of, a designated person or entity where that person knows, or has reasonable cause to suspect, the individual or entity is designated. Offences under TAFA can be committed by anyone in the UK and extends to conduct by a UK national or UK incorporated/constituted company that takes place wholly or partly outside the UK. The Treasury does not proactively identify targets for asset freezes. Rather, the Treasury is advised by operational partners, including the police and the United Kingdom Intelligence Community, who identify possible targets for asset freezes and present the evidence supporting the freeze to the Treasury to consider. It is also possible for third countries to identify possible targets.

The UK’s terrorist asset-freezing regime contains robust safeguards to ensure the restrictions remain proportionate. Under section 2(1)(a) of TAFA, the Treasury may only designate persons where it has reasonable grounds to believe that they are, or have been, involved in terrorist activity, or are owned, controlled (directly or indirectly) or acting on behalf of or at the direction of someone who is, or has been, involved in terrorist activity. Under section 2(1)(b), financial restrictions may only be applied where the Treasury considers it necessary for purposes connected with protecting members of the public (anywhere in the world) from terrorism. The requirements of both section 2(1)(a) and 2(1)(b) must be met for a designation to be made. In addition to meeting the statutory test, a designation will only be imposed where an asset freeze is considered to be the most proportionate tool available.

In addition, there are a number of other safeguards to ensure that the UK’s terrorist asset- freezing regime is operated fairly and proportionately, which include the following:

- The Treasury may grant licences to allow exceptions to the asset freeze, ensuring that human rights are taken account of, whilst also ensuring that funds are not diverted to terrorist purposes.

- Designations expire after a year unless reviewed and renewed. The Treasury may only renew a designation where the requirements under sections 2(1)(a) and (b) of TAFA continue to be met.

- Designations must generally be publicised but can be notified on a restricted basis and not publicised when one of the conditions in section 3(3) of TAFA is met. Those conditions are that:

the Treasury believe that the designated person is under 18;

or the Treasury consider the disclosure of the designation should be restricted:

- i) in the interests of national security;

- ii) for reasons connected with the prevention or detection of serious crime; or

-

iii) in the interests of justice.

- Where a designation is notified on a restricted basis, the Treasury can also specify that people informed of the designation treat the information as confidential.

- A designated person (or entity) has a right of appeal against a designation decision in the High Court, and anyone affected by a licensing decision (including the designated person (or entity)) can challenge on judicial review grounds any licensing or other decisions of the Treasury under TAFA. There is a closed material procedure available for such appeals or challenges using specially cleared advocates to protect closed material whilst ensuring a fair hearing for the affected person.

- Individuals are notified, as far as it is in the public interest to do so, of the reasons for their designation. This information is kept under review and if it becomes possible to release more detailed reasons the Treasury will do so. The Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, Jonathan Hall QC, may conduct a review of, and report on, the operation of TAFA.

- The Treasury is required to report to Parliament, quarterly, on its operation of the UK’s asset freezing regime. In addition, the Treasury also reports on the UK’s operation of the EU and UN terrorist asset-freezing regimes. A link to these reports can be found here: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/operation-of-the-uks-counter- terrorist-asset-freezing-regime-quarterly-report-to-parliament

The following table sets out the volumes of funds frozen, and number of accounts frozen as at 31 December 2018 under TAFA:

| TAFA 2010 | |

|---|---|

| Total funds frozen (GBP equivalent at the end of the quarter) | £9,000 |

| Total accounts frozen (at the end of the quarter) | 6 |

| Accounts frozen (during the quarter) | 0 |

| Accounts unfrozen (during the quarter) | 0 |

The following table sets out the number of natural and legal persons, entities or bodies designated under TAFA as at 31 December 2018:

| TAFA 2010 | |

|---|---|

| Total number of designations (at the end of the quarter) | 20 |

| Total number of designated individuals | |

| (at the end of the quarter) | 14 |

| Total number of designated groups and entities (at the end of the quarter) | 6 |

| New public designations (during the quarter) | 0 |

| New confidential designations[footnote 7] (during the quarter) | 0 |

| Total number of current confidential designations (at the end of the quarter) | 0 |

| Total delistings (during the quarter) | 0 |

| Total renewals of designations by HMT (during the quarter) | 5 |

Listings

- 1. TAFA is one of several CT financial sanctions regimes. Information on all the regimes and the current financial sanctions designations can be found on the OFSI website: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/office-of-financial-sanctions-implementation

- 2. Consolidated list of all the individuals, organisations and businesses subject to financial sanctions in the UK: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/financial-sanctions-consolidated-list-of-targets/consolidated-list-of-targets

- 3. Current designations under the UN ISIL-AQ regime & EU Regulation 2016/1686 (Designations under this regulation will be identified as “EU Listing only”): https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/current-list-of-designated-persons-al-qaida

-

4. Current designations under TAFA and EU 2580/2001 found at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/current-list-of-designated-persons-terrorism-and-terrorist-financing

- ‘UK listing only’ – listed under TAFA 2010 only

- ‘Both UK and EU listing’ – designated under TAFA 2010 and under the EU’s asset freezing regime 2580/2001

- ‘EU listing only’ – listed under EU’s asset freezing regime. The prohibitions are found in Council Regulation (EC) No 2580/2001 with enforcement and associated penalties provided by TAFA 2010

UK’s withdrawal from the EU

In connection with the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, the government intends to repeal Part 1 of the Terrorist Asset-Freezing etc. Act 2010 (TAFA). This repeal is provided for in section 59 of the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (SAMLA).

The Counter-Terrorism (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 and Counter-Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, which were made in March 2019 using SAMLA powers, will enable the UK to continue to impose autonomous counter-terrorism sanctions when TAFA is repealed. The first sanctions regime aims to further the prevention of terrorism in the UK or elsewhere and protect UK national security interests, and will be led by HM Treasury. The second aims to further the prevention of terrorism in the UK or elsewhere and will be led by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Together they will ensure the UK implements its international obligations under UN Security Council Resolution 1373.

Finally, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office has also made the ISIL (Da’esh) and Al-Qaida (United Nations Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, which will give effect to the UK’s obligations under UNSCR 2368 and implement the UN sanctions regime in relation to ISIL (Da’esh) and Al-Qaida.

Further information about the regimes can be found here:

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-counter-terrorism-sanctions, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-international-counter-terrorism-sanctions, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-sanctions-on-isil-daesh-and-al-qaida.

5.4 Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures

Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPIMs) allow the Home Secretary to impose a powerful range of disruptive measures on a small number of people who pose a real threat to our security but who cannot be prosecuted or, in the case of foreign nationals, deported. These measures can include overnight residence requirements (including relocation to another part of the UK), police reporting, an electronic monitoring tag, exclusion from specific places, limits on association, limits on the use of financial services and use of telephones and computers, and a ban on holding travel documents.

It is the Government’s assessment that, for the foreseeable future, there will remain a small number of individuals who pose a real threat to our security but who cannot be either prosecuted or deported, and there continues to be a need for powers to protect the public from the threat posed by these people.

The use of TPIMs is subject to stringent safeguards. Before the Secretary of State decides to impose a TPIM notice on an individual, he must be satisfied that five conditions are met, as set out at section 3 of the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011 (TPIM Act)[footnote 8].

The conditions are that:

- the Secretary of State considers, on the balance of probabilities, that the individual is, or has been, involved in terrorism-related activity (the “relevant activity”);

- where the individual has been subject to one or more previous TPIM orders, that some or all of the relevant activity took place since the most recent TPIM notice came into force;

- the Secretary of State reasonably considers that it is necessary, for purposes connected with protecting members of the public from a risk of terrorism, for Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures to be imposed on the individual;

- the Secretary of State reasonably considers that it is necessary, for purposes connected with preventing or restricting the individual’s involvement in terrorism-related activity, for the specified Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures to be imposed on the individual; and

- the court gives permission, or the Secretary of State reasonably considers that the urgency of the case requires Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures to be imposed without obtaining such permission.

The Secretary of State must apply to the High Court for permission to impose the TPIM notice on the individual, except in cases of urgency where the notice must be immediately referred to the court for confirmation.

All individuals upon whom a TPIM notice is imposed are automatically entitled to a review hearing at the High Court relating to the decision to impose the notice and the individual measures in the notice. They may also appeal against any decisions made subsequent to the imposition of the notice, i.e. a refusal of a request to vary a measure, a variation of a measure without their consent, or the revival or extension of their TPIM notice. The Secretary of State must keep under review the necessity of the TPIM notice and specified measures during the period that a TPIM notice is in force.

A TPIM notice initially lasts for one year and can only be extended for one further year. No new TPIM may be imposed on the individual after that time unless the Secretary of State considers, on the balance of probabilities, that the individual has engaged in further terrorism-related activity since the imposition of the notice.

The Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 enhanced the powers available in the TPIM Act, including introducing the ability to relocate a TPIM subject elsewhere in the UK (up to a maximum of 200 miles from their normal residence, unless the TPIM subject agrees otherwise) and a power to require a subject to attend meetings as part of their ongoing management, such as with the probation service or Jobcentre Plus staff. The Home Secretary published factors that are considered appropriate to take into account when considering whether to relocate a subject under the overnight residence measure[footnote 9]. These are: the need to prevent or restrict a TPIM subject’s involvement in terrorism-related activity; the personal circumstances of the individual; proximity to travel links including public transport, airports, ports and international rail terminals; the availability of services and amenities, including access to employment, education, places of worship and medical facilities; proximity to prohibited associates; proximity to positive personal influences; location of UK resident family members; and community demographics.

The last Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation review of the operation of the TPIM Act was published in October 2017. Changes made to the Independent Reviewer’s remit through the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 allowed for a more flexible arrangement in respect of the frequency of this review.

Under the TPIM Act the Secretary of State is required to report to Parliament, as soon as reasonably practicable after the end of every relevant three month period, on the exercise of his TPIM powers.

The most recent published reports cover the period from 1 December 2018 to 28 February 2019 and 1 March 2019 to 31 May 2019.

As at 28 February 2019, there were four TPIM notices in force, all of which related to British citizens. During the reporting period:

- no notices were extended

- no notices were revoked

- no notices were revived

- two individuals were subject to the relocation measure.

As at 31 May 2019, there were three TPIM notices in force, all of which related to British Citizens. During the reporting period:

- No notices were extended

- One notice was revoked

- One TPIM subject was subject to the relocation measure.

5.5 Royal Prerogative

The Royal Prerogative is a residual power of the Crown which is used widely across Government in a number of different contexts. Secretaries of State exercise a range of prerogative powers in different contexts and the courts have upheld the legitimacy of prerogative powers that are not based in primary legislation.

A passport remains the property of the Crown at all times. HM Passport Office issues or refuses passports under the Royal Prerogative and there are a number of grounds for withdrawal or refusal. The Home Secretary has the discretion, under the Royal Prerogative, to refuse to issue or to withdraw a British passport on public interest grounds. This criterion supports the use of the Royal Prerogative in national security cases. The Royal Prerogative is therefore an important tool to disrupt individuals who seek to travel on a British passport to engage in terrorism-related activity and who would return to the UK with enhanced capabilities to do the public harm.

On 25 April 2013, the Government redefined the public interest criteria to refuse or withdraw a passport in a Written Ministerial Statement to Parliament[footnote 10].

The policy allows passports to be withdrawn, or refused, where the Home Secretary is satisfied that it is in the public interest to do so. This may be the case for:

“A person whose past, present or proposed activities, actual or suspected, are believed by the Home Secretary to be so undesirable that the grant or continued enjoyment of passport facilities is contrary to the public interest.” (Written Ministerial Statement to Parliament 25 April 2013)

The application of discretion by the Home Secretary will primarily focus on preventing overseas travel, but there may be cases in which the Home Secretary believes that the past, present or proposed activities (actual or suspected) of the applicant or passport holder should prevent their enjoyment of a passport facility whether or not overseas travel is a critical factor.

Under the public interest criterion, in relation to national security, the Royal Prerogative was exercised to deny access to British passport facilities to:

- five individuals in 2018;

- 14 individuals in 2017;

- 17 individuals in 2016;

- 23 individuals in 2015;

- 24 individuals in 2014; and

- six individuals in 2013.

An individual may ask for a review of the decision or apply for a new passport at any time (prompting a review of the decision). In addition, if significant new information comes to light a case review may be triggered. Since 2014, there have been:

- 10 reviews in 2018;

- 21 reviews in 2017;

- six reviews in 2016;

- nine reviews in 2015; and

- two reviews in 2014.

As a result of these reviews, as of 31 December 2018, passport facilities have been restored to 13 individuals.

5.6 Seizure and Temporary Retention of Travel Documents

Schedule 1 to the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 enables police officers at ports to seize and temporarily retain travel documents to disrupt immediate travel, when they reasonably suspect that a person intends to travel to engage in terrorism related activity outside the UK.

The temporary seizure of travel documents provides the authorities with time to investigate an individual further and consider taking longer term disruptive action such as prosecution, exercising the Royal Prerogative to withdraw or refuse to issue a British passport, or making a person subject to a TPIM order.

Travel documents can only be retained for up to 14 days while investigations take place. The police may apply to the courts to extend the retention period but this must not exceed 30 days in total.

Since January 2015, the power has been exercised:

- five times in 2018

- 14 times in 2017;

- 15 times in 2016; and

- 24 times in 2015.

Of the above, travel documents were retained beyond the 14-day period in 38 instances.

5.7 Exclusions

The Secretary of State (usually the Home Secretary) may decide to exclude a non-European Economic Area (EEA) national if he or she considers that the person’s presence in the UK would not be conducive to the public good. If a decision to exclude is taken it would need to be reasonable, consistent and proportionate based on the evidence available. The exclusion power arises under the Royal Prerogative. It is normally used in circumstances involving national security, unacceptable behaviour (such as extremism), international relations or foreign policy, and serious and organised crime. European Economic Area nationals and their family members may be excluded from the UK on grounds of public policy or public security, if they are considered to pose a genuine, present and sufficiently serious threat affecting one of the fundamental interests of society.

Between 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2017 the government excluded 26 people from the United Kingdom, all on national security grounds. There were 36 exclusions made between 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2018, including 32 exclusions on national security grounds, 3 exclusions on unacceptable behaviour grounds, and one on the basis of organised crime concerns.

The Secretary of State uses exclusion powers when justified and based on all available evidence. In all matters, the Secretary of State must act reasonably, proportionately and consistently. Exclusion powers are very serious and the Government does not use them lightly. This power can be used to prevent the return to the UK of foreign nationals suspected of taking part in terrorist related activity in Syria due to the threat they would pose to public security.

5.8 Temporary Exclusion Orders

The Counter Terrorism and Security Act 2015 introduced temporary exclusion orders (TEOs). This is a statutory power which allows the Secretary of State (usually the Home Secretary) to disrupt and control the return to the UK of a British citizen who has been involved in terrorism- related activity outside the UK. The tool is important in helping to protect the public from any risk posed by individuals involved in terrorism-related activity abroad, including in Syria or Iraq.

A TEO makes it unlawful for the subject to return to the UK without engaging with the UK authorities. It is implemented through cancelling the TEO subject’s travel documents and adding them to watch lists (including the authority to carry (‘no fly’) list), ensuring that when individuals do return, it is in a manner which the UK Government controls. The subject of a TEO commits an offence if, without reasonable excuse, he or she re-enters the UK not in accordance with the terms of the order.

A TEO also allows for certain obligations to be imposed once the individual returns to the UK and during the validity of the order. These might include reporting to a police station, notifying the police of any change of address, or attending appointments such as a de-radicalisation programme. The subject of a TEO also commits an offence if, without reasonable excuse, he or she breaches any of the conditions imposed.

There are two stages of judicial oversight for TEOs. The first is a court permission stage before a TEO is imposed by the Secretary of State. The second is an optional statutory review of the decision to impose a TEO and any in-country obligations after the individual has returned to the UK.

The power came into force in the second quarter of 2015. No TEOs were imposed in 2016. The number of TEOs imposed from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2017 is 9, on 3 males and 6 females. Between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2018, 16 TEOs were imposed on 14 males and 2 females.

Of this number, 4 (1 male and 3 females) returned to the UK in 2017, and 5 (2 males and 3 females) returned to the UK in 2018.

5.9 Deprivation of British Citizenship

The British Nationality Act 1981 provides the Secretary of State with the power to deprive an individual of their British citizenship in certain circumstances. Such action paves the way for possible immigration detention, deportation or exclusion from the UK and otherwise removes an individual’s right of abode in the UK.

The Secretary of State may deprive an individual of their British citizenship if satisfied that such action is ‘conducive to the public good’ or if the individual obtained their British citizenship by means of fraud, false representation or concealment of material fact.

When seeking to deprive a person of their British citizenship on the basis that to do so is ‘conducive to the public good’, the law requires that this action only proceeds if the individual concerned would not be left stateless (no such requirement exists in cases where the citizenship was obtained fraudulently).

The Government considers that deprivation on ‘conducive’ grounds is an appropriate response to activities such as those involving:

- national security, including espionage and acts of terrorism directed at this country or an allied power;

- unacceptable behaviour of the kind mentioned in the then Home Secretary’s statement of 24 August 2005 (‘glorification’ of terrorism etc)[footnote 11];

- war crimes; and

- serious and organised crime.

By means of the Immigration Act 2014, the Government introduced a power whereby in a small subset of ‘conducive’ cases – where the individual has been naturalised as a British citizen and acted in a manner seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the UK – the Secretary of State may deprive that person of their British citizenship, even if doing so would leave them stateless. This action may only be taken if the Secretary of State has reasonable grounds for believing that the person is able, under the law of a country outside the United Kingdom, to become a national of that country.

In practice, this power means the Secretary of State may deprive and leave a person stateless (if the vital interest test is met and they are British due to naturalising as such), if that person is able to acquire (or reacquire) the citizenship of another country and is able to avoid remaining stateless.

David Anderson QC undertook the first statutory review of the additional element of the deprivation power, as required by the Immigration Act 2014. His report was published on 21 April 2016[footnote 12]. A subsequent review of this power is anticipated to be conducted during 2019. Since its introduction in July 2014, there have been no individuals deprived of British citizenship through the use of this power.

The Government considers removal of citizenship to be a serious step, one that is not taken lightly. This is reflected by the fact that the Home Secretary personally decides whether it is conducive to the public good to deprive an individual of British citizenship.

Between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2018, 21 people were deprived of British citizenship on the basis that to do so was ‘conducive to the public good’[footnote 13].

5.10 Deportation with Assurances

Where prosecution is not possible, the deportation of foreign nationals to their country of origin may be an effective alternative means of disrupting terrorism-related activities. Where there are concerns for an individual’s safety on return, government to government assurances may be used to achieve deportation in accordance with the UK’s human rights obligations.

Deportations with Assurances (DWA) enables the UK to reduce the threat from terrorism by deporting foreign nationals who pose a risk to our national security, while still meeting our domestic and international human rights obligations. This includes Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which prohibits torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Assurances in individual cases are the result of careful and detailed discussions, endorsed at a very high level of government, with countries with which we have working bilateral relationships. We may also put in place arrangements – often including monitoring by a local human rights body – to ensure that the assurances can be independently verified. The use of DWA has been consistently upheld by the domestic and European courts.

The then Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, David Anderson QC, reviewed the legal framework of DWA and examined whether the process can be improved, including by learning from the experiences of other countries, his report was published in July 2017[footnote 14]. Mr Anderson noted that the UK had taken the lead in developing rights-compliant procedures for DWA; that future DWA proceedings were likely to take less time now that the central legal principles have been established by the highest courts; that for as long as the UK remains party to the ECHR, the provisions of the ECHR will remain binding on the UK in international law; that the key consideration in developing safety on return processes was whether compliance with assurances can be objectively verified; and that assurances could be tailored to particular categories of deportee, or to particular outcomes.

The Government published a response to Mr Anderson’s report in October 2018[footnote 15]. The Government response acknowledged Mr Anderson’s positive views on the UK’s use of DWA and advised that future use of DWA respond to operational needs via a flexible, adaptable approach, with urgently negotiated agreements being made as needed. The response confirmed that DWA remained appropriate in relevant cases, and would remain one of the tools available to this Government

A total of 12 people have been removed from the UK under DWA arrangements. There have been no DWA removals since 2013 and new agreements would need to be negotiated for any future cases.

5.11 Proscription

Proscription is an important tool enabling the prosecution of individuals who are members or supporters of, or are affiliated with, a terrorist organisation. It can also support other disruptive powers including prosecution for wider offences, immigration powers such as exclusion, and terrorist asset freezing. The resources of a proscribed organisation are terrorist property and are therefore liable to be seized.

Under the Terrorism Act 2000, the Home Secretary may proscribe an organisation if they believe it is concerned in terrorism. For the purposes of the Act, this means that the organisation:

- commits or participates in acts of terrorism;

- prepares for terrorism;

- promotes or encourages terrorism (including the unlawful glorification of terrorism); or

- is otherwise concerned in terrorism.

“Terrorism” as defined in the Act means the use or threat of action which: involves serious violence against a person; involves serious damage to property; endangers a person’s life (other than that of the person committing the act); creates a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or section of the public; or is designed seriously to interfere with or seriously to disrupt an electronic system. The use or threat of such action must be designed to influence the government or an international governmental organisation or to intimidate the public or a section of the public and be undertaken for the purpose of advancing a political, religious, racial or ideological cause.

If the statutory test is met, there are other factors which the Home Secretary will take into account when deciding whether or not to exercise the discretion to proscribe. These discretionary factors include:

- the nature and scale of an organisation’s activities;

- the specific threat that it poses to the UK;

- the specific threat that it poses to British nationals overseas;

- the extent of the organisation’s presence in the UK; and

- the need to support other members of the international community in the global fight against terrorism.

The proscription offences are set out in sections 11 to 13 of the Terrorism Act 2000 and were amended by the Counter Terrorism and Border Security Act 2019 by adding the offences of:

- the reckless expression of support for a proscribed organisation;

- publishing an image of an article such as a flag or logo.

This means it is now a criminal offence for a person in the UK to:

- belong, or profess to belong, to a proscribed organisation in the UK or overseas (section 11 of the Act);

- invite support for a proscribed organisation (the support invited need not be material support, such as the provision of money or other property, and can also include moral support or approval) (section 12(1));

- express an opinion or belief that is supportive of a proscribed organisation, reckless as to whether a person to whom the expression is directed will be encouraged to support a proscribed organisation (section 12(1A));

- arrange, manage or assist in arranging or managing a meeting in the knowledge that the meeting is to support or further the activities of a proscribed organisation, or is to be addressed by a person who belongs or professes to belong to a proscribed organisation (section 12(2)); or to address a meeting if the purpose of the address is to encourage support for, or further the activities of, a proscribed organisation (section 12(3));

- wear clothing or carry or display articles in public in such a way or in such circumstances as to arouse reasonable suspicion that the individual is a member or supporter of a proscribed organisation (section 13); and

- publish an image of an item of clothing or other article, such as a flag or logo, in the same circumstances (section 13(1A)).

The penalties for proscription offences under sections 11 and 12 are a maximum of 10 years in prison and/or a fine. The maximum penalty for a section 13 offence is six months in prison and/or a fine not exceeding £5,000.

Under the Terrorism Act 2000, a proscribed organisation, or any other person affected by a proscription, may submit a written application to the Home Secretary, asking that a determination be made whether a specified organisation should be removed from the list of proscribed organisations. The application must set out the grounds on which it is made. The precise requirements for an application are contained in the Proscribed Organisations (Applications for Deproscription etc) Regulations 2006 (SI 2006/2299).

The Home Secretary is required to determine a deproscription application within 90 days from the day after it is received. If the deproscription application is refused, the applicant may appeal to the Proscribed Organisations Appeals Commission (POAC). POAC will allow an appeal if it considers that the decision to refuse deproscription was flawed, applying judicial review principles. Either party can seek leave to appeal POAC’s decision at the Court of Appeal.

If the Home Secretary agrees to deproscribe the organisation, or an appeal by the applicant is successful, the Home Secretary will lay a draft order before Parliament removing the organisation from the list of proscribed organisations. The Order is subject to the affirmative resolution procedure so must be agreed by both Houses of Parliament.

Under the same legislation proscription decisions in relation to Northern Ireland are a matter for the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, including deproscription applications for Northern Ireland groups.

Since 2000, the following four groups have been deproscribed;

- the Mujaheddin e Khalq (MeK) also known as the People’s Mujaheddin of Iran (PMOI) was removed from the list of proscribed groups in June 2008 as a result of judgments of POAC and the Court of Appeal;

- the International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF) was removed from the list of proscribed groups in March 2016 following receipt of an application to deproscribe the organisation;

- Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin (HIG) was removed from the list of proscribed groups in December 2017 following receipt of an application to deproscribe the organisation; and

- Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) was removed from the list of proscribed groups in November 2019 following receipt of an application to deproscribe the organisation.

There are currently 75[footnote 16] terrorist organisations proscribed under the Terrorism Act 2000. In addition, there are 14 organisations in Northern Ireland that were proscribed under previous legislation.

The most recent proscription orders came in to force in February 2020, proscribing Sonnenkrieg Division (SKD), consolidating the Partiya Karkeren Kurdistani (PKK) and Teyre Azadiye Kurdistan (TAK) proscriptions and also recognising Hêzên Parastina Gel (HPG) as an alias of the PKK. In addition, an Order was also laid to recognise the System Resistance Network (SRN) as an alias of National Action.

Information about these groups’ aims is given to Parliament at the time that they are proscribed. These details, for each proscribed international terrorist organisation, are included at ANNEX A.

5.12 Closed Material Procedure

The Justice and Security Act 2013 introduced a statutory closed material procedure (CMP), which allows for sensitive material, i.e. material the disclosure of which would be damaging to national security, to be examined in civil court proceedings[footnote 17]. CMPs ensure that government departments, the UK Intelligence Community, law enforcement bodies and indeed any other party to proceedings have the opportunity to properly defend themselves or bring proceedings in the civil court, where sensitive national security material is considered by the court to be involved. CMPs allow the courts to scrutinise matters that were previously not heard because disclosing the relevant material publicly would have damaged national security.

A declaration permitting closed material applications is an “in principle” decision made by the court about whether a CMP should be available in the relevant case. This decision is normally based on an application from a party to the proceedings, usually a Secretary of State. However, the court can also make a declaration of its own motion.

Where a Secretary of State makes the application, the court must first satisfy itself that the Secretary of State has considered making, or advising another person to make, an application for public interest immunity in relation to the material. The court must also be satisfied that material would otherwise have to be disclosed which would damage national security and that closed proceedings would be in the interests of the fair and effective administration of justice. Should the court be satisfied that the above criteria are met, then a declaration may be made. During this part of proceedings, a Special Advocate may be appointed to act in the interests of parties excluded from proceedings.

Once a declaration is made, the Act requires that the decision to proceed with a CMP is kept under review, and the CMP may be revoked by a judge at any stage of proceedings, if it is no longer in the interests of the fair and effective administration of justice.

A further hearing, following a declaration, determines which parts of the case should be dealt with in closed proceedings and which should be released into open proceedings. The test being considered here remains whether the disclosure of such material would damage national security.

The Justice and Security Act requires the Secretary of State (in practice, the Justice Secretary) to prepare (and lay before Parliament) a report on CMP applications and subsequent proceedings under section 6 of the Act. Under section 12(4) of the Act, the report must be prepared and laid before Parliament as soon as reasonably practicable after the end of the twelve-month period to which the report relates. The first report covered the period 25 June 2013 (when the Act came into force) to 24 June 2014[footnote 18]. The most recent report, relating to the period 25 June 2017 to 24 June 2018, was published on 13 December 2018[footnote 19].

In the latest reporting period from 2017 to 2018, there were 13 applications for a declaration that a CMP application may be made (eleven of them by a Secretary of State, and two by persons other than a Secretary of State). There were five declarations that a CMP application may be made in proceedings during the reporting period (three in response to applications made by the Secretary of State during the reporting period, and two in response to applications made by the Secretary of State during previous reporting periods). No declarations were revoked during the reporting period.

There were two final judgments made during this period regarding the outcome of the application for a CMP. None were closed judgments. There were four final judgments made during this period to determine the outcome of substantive proceedings. One of these was a closed judgment.

5.13 Tackling Online Terrorist Content

Terrorist groups use the internet to spread propaganda designed to radicalise, recruit and inspire vulnerable people, and to incite, provide information to enable, and celebrate terrorist attacks. Our objective is to ensure that there are no safe spaces online for all forms of terrorists to promote or share their extreme views.

In 2010, we set up the police Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU), based in the Metropolitan Police. The CTIRU has referred over 310,000 pieces of online terrorist content to tech companies for removal, and the Unit has also informed the design of the EU Internet Referral Unit based at Europol.

The Government has been clear that tech companies cannot be reliant on government referrals, and that they need to act proactively and more quickly to remove all forms of terrorist content from their platforms. We have pressed companies to increase the use of technology to automate the detection and removal of content where possible. As a result of continued engagement, companies have expanded the use of automated removals. Additionally, we have developed technical solutions to aid in detection and removal of terrorist content. Working in partnership with UK Data Science companies, these tools are offered free of charge and help to prevent terrorist content from ever reaching the internet as well as enabling companies to take quicker action on terrorist content that has been uploaded.

As the threat of terrorism disperses across a range of different and new platforms, it is critical that a broad sweep of companies tackle the terrorist threat working together as one body. As part of this, we continue to work closely with the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT), which is an international, industry-led forum to tackle terrorist use of the internet. We welcome the GIFCT’s announcement at the 2019 UN General Assembly to become an independent organisation led by an Executive Director and supported by dedicated teams, and look forward to sitting on the newly-established Independent Advisory Committee.

In recognition that more needs to be done to tackle online harms, including terrorist use of the internet, the Government published the Online Harms White Paper in April 2019. The White Paper set out our plans to make the UK the safest place in the world to be online and hold companies to account for tackling a wide range of online harms. It included proposals for companies to take particularly robust action against the most serious illegal online offending, such as terrorism and child sexual exploitation and abuse. A public consultation on the White Paper ran April-July 2019. The Queen’s Speech committed the Government to ‘develop legislation to improve internet safety for all’. Similarly, the Conservative manifesto for the 2019 General Election set out a commitment to address online harms. An initial consultation response was published in February 2020 clarifying further details and announcing that government was minded to appoint Ofcom as the online harms regulator. The initial response will be followed by the publication of a full response and two interim codes of practice in relation to terrorist and CSEA content or activity in Spring 2020. The Government will be undertaking further work to address online harms, such as the publication of a media literacy strategy and an interim government transparency report.

In addition to encouraging technology companies to play their part in preventing terrorist use of the internet, the Government has changed the law through the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act 2019, so that people who view terrorist content online could face up to 15 years in prison. This change strengthens the existing offence, so that it applies to material that is viewed or streamed online.

Alongside our effort to squeeze the space terrorists operate online, we work with a range of civil society groups to counter extremist ideologies and to support people in communities already working to reject those narratives.

5.14 Tackling Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

The Government is undertaking a significant programme of work to enhance the UK’s response to online child sexual exploitation and abuse (CSEA).

The then Home Secretary made a speech in September 2018 where he demanded industry to do more to tackle Online CSEA. He outlined five key asks of industry:

- block child sexual abuse material as soon as companies detect it being uploaded.

- stop child grooming taking place on their platforms.

- work with us to shut down live-streamed child abuse. 4. be more forward-learning in helping law enforcement agencies deal with these types of crimes.

- display a greater deal of openness and transparency, and a willingness to share best practice and technology between companies

In April 2019, the then Home Secretary annouced an Online Harms White Paper in collaboration with the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. The Online Harms White Paper sets out our plans for world-leading legislation to make the UK the safest place in the world to be online. This will establish in law a new duty of care on companies towards their users, especially children and other vulnerable groups, which will be overseen by an independent regulator. An initial response to the Online Harms White Paper consultation was published in February 2020, and a full consultation response will be published in Spring 2020, alongside an interim Code of Practice on online CSEA. This interim Code of Practice will provide guidance to companies on how to tackle online CSEA content and activity on a voluntary basis until the new regulator becomes operational.

Collaborative working between Police forces and the NCA is resulting in an average of around 500 arrests each month for online CSEA offences, and the safeguarding of around 700 children each month. A Joint Operations Team, a collaborative venture between the NCA and GCHQ, is targeting the most sophisticated offenders. In addition, the Home Secretary recently announced an additional £20 million funding over three years has been provided to the Regional Organised Crime Units (ROCUs) to significantly increase the undercover online (UCOL) capability which is being used to target online grooming of children.

Internet users in the UK, including members of the public, who find illegal images of child sexual abuse can report them to the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF). The web pages containing such images can be blocked by Internet Service Providers (ISPs). The IWF is an independent organisation that proactively searches the internet for child sexual abuse images and acts as the UK hotline for the reporting of criminal content online. The purpose of the IWF is to minimise the availability of child sexual abuse images hosted anywhere in the world and non- photographic child sexual abuse images hosted in the UK.

The IWF has authority to hold and analyse this content through agreement with the Crown Prosecution Service and the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) - now the National Police Chief’s Council (NPCC). In 2019, the IWF found 132,700 URLs containing child sexual abuse imagery – a 26% increase from 2018. If the site hosting the image is hosted in the UK, the IWF will pass the details to law enforcement (the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Command of the National Crime Agency or local police forces) and the website host will be asked to take down the webpage.

If outside the UK, the IWF will alert the hotline in the relevant country to enable them to work with law enforcement in that country to take down the webpage. In countries where a hotline does not exist, this liaison is carried out via INTERPOL. Although the IWF is not part of Government, the Home Office maintains regular contact with the organisation, and Ministerial responsibility for policy relating to online child sexual exploitation. The responsibility for the legislation in respect of illegal indecent imagery of children and sexual contact with a child online sits with the Ministry of Justice.

The Home Office continued its investment in Project Arachnid, which is a collaboration between international hotlines that includes web-crawler technology developed by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection that is being deployed across websites, forums, chat services and newsgroups to detect known illegal content on the open web. Project Arachnid speeds up the time it takes to locate a known indecent image on the internet, without the need for human eyes. It also provides an Application Programming Interface (API) which allows companies who wish to make use of the tool to upload images suspected of being child abuse material to be checked against Arachnid’s database of imagery or to be reviewed by analysts. It also enables companies who provide hosting to websites to check URLs against Arachnid’s crawler. As of 13 June 201920, more than 71 billion images have been processed, more than 3.8 million notices have been sent to providers and 85% of the notices issued relate to victims who are not know to have been identified by the police. The Crawler is currently detecting over 500,000 unique images per month. The Canadian Centre for Child Protection has partnered with the US National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children to expand the pool of analysts and to reduce duplication between organisations as part of the Project.

The WePROTECT Global Alliance strategy, published in 2015, sets out the high-level strategic goals of the initiative: to build national action with countries and to galvanise global action through high-level political engagement and work with the technology industry. To-date WePROTECT Global Alliance has focused on implementing its public strategy, to engage high- level decision makers and achieve action on the ground. Its multi-stakeholder nature is unique in this field, with 97 countries, 27 global technology companies, 30 leading Non-Governmental Organisations and eight regional organisations signed up to the initiative. All member governments have signed commitments to develop a comprehensive national response to tackle online child sexual exploitation.

To date, our £30 million investments in the Fund to End Violence Against Children have supported over 30 projects in 20 countries delivering; support to victims, technical solutions to detect and prevent offending, support to law enforcement and educational campaigns on ways to keep children safe online. Through our investment, over 48,000 children have been reached by prevention and awareness raising campaigns in over 20 countries, as well as 4,500 caregivers and educational providers. In February 2018, WePROTECT Global Alliance published the Global Threat Assessment highlighting the growing dangers posed to children by the growth of smart phone technology and an expanding online community of tech offenders. Its second Global Threat Assessment was published in December 2019 and was accompanied by a Global Strategic Response framework to coordinate global action across governments, industry and civil society against online child sexual exploitation. These two products were launched at a global summit to tackle online child sexual exploitation, co-hosted by the WePROTECT Global Alliance, the UK Government and the African Union in December 2019 at the African Union’s headquarters in Addis Abba, Ethiopia. The summit brought together over 400 senior representatives from governments, industry and civil society organisations.

At the 2019 Five Country Ministerial, Five Countries agreed with industry representatives to collaborate to design a set of voluntary principles that will ensure online platforms and services have the systems needed to stop the viewing and sharing of child sexual abuse material, the grooming of children online, and the livestreaming of child sexual abuse and the ability to report such offences to law enforcement.

As a result, the Five Countries developed the Voluntary Principles to Counter Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, in consultation with six leading technology companies and a broad range of other experts from industry, civil society and academia. The Voluntary Principles were published on 5 March 2020.

The Five Country governments have partnered with the WePROTECT Global Alliance—an international body comprising government, industry and civil society members—to promote the Principles globally and drive collective industry action. The WePROTECT Global Alliance will also connect subject matter experts to share best practice and analyse the evolving threat environment to identify gaps in the global response. Five Country Governments will work closely with the WePROTECT Global Alliance to ensure the Principles remain fit-for-purpose for emerging trends and threats.

6. MI5 Investigations and Closed SOI’s

MI5 is investigating approximately 3000 subjects of interest (SOIs) across 600 priority investigations. Each SOI will have a different amount of investigative resource allocated to them depending on the threat they are judged to post. A significant number of these 3,000 SOIs are located overseas.

MI5 only investigates SOIs when it believes the individual may pose a threat. As soon as MI5 judges that an SOI no longer poses a threat, that SOI is downgraded and placed in a ‘Closed’ category (called ‘CSOI’, or Closed Subject of Interest). This does not mean these SOIs will never pose a threat again, but merely that their current level of threat is not judged to be sufficient to prioritise allocating investigative resource against them. This situation could change at any time requiring MI5 to re-assess the threat they pose and, where necessary, begin investigating them again. For example, a CSOI might re-engage in their previous terrorist activity.

Since 2017, as part of the joint MI5-Counter-Terrorism Policing Operational Improvement Review following the 2017 terrorist attacks, MI5 has reviewed the way it manages this pool of CSOIs to ensure the right monitoring measures are in place to alert MI5 if the CSOI begins to pose a threat that might justify renewed investigation. To assist with efficiently managing this pool of CSOIs, a new system of sub-categories has been applied so that each CSOI is allocated to a specific category depending on the potential risk of them re-engaging. In the sub-categories where MI5 judges there to be some risk of re-engaging in terrorist activity (this risk varies dependent on the sub-category), there are currently over 40,000 CSOIs.

In 2017, the public figure for the number of CSOIs was 20,000. A substantial element of the increase to over 40,000 is the inclusion of individuals who have never travelled to the UK but whose details have been passed to MI5 by foreign intelligence services, in order that MI5 be alerted should they enter the UK. This new figure is not, therefore, directly comparable to the previous 20,000 figure and it does not mean there are now over twice as many CSOIs at risk of re-engagement.

Nevertheless, by its very nature, the CSOI figure will always increase year on year. MI5 is constantly opening new investigations into individuals who come to its attention and then closing SOIs when it is confident it has mitigated any threat they pose. Individuals generally remain in a CSOI category unless they re-engage in terrorist activity (in which case they are moved back into a priority investigation), or until a substantial amount of time has passed. This inevitably means that more individuals enter the CSOI pool than leave it.

7. Oversight

7.1 The Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation

The current Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation (IRTL), Jonathan Hall QC, took up his appointment on 23 May 2019. The IRTL is appointed by the Home Secretary through open competition in accordance with the Governance Code on Public Appointments.

The role of the IRTL is to keep under review the operation of a range of UK counter-terrorism legislation to ensure that it is effective, fair and proportionate. This helps to provide transparency, inform public and political debate, and maintain public and Parliamentary confidence in the exercise of counter-terrorism powers, by providing independent and ongoing oversight of UK terrorism legislation as the legislative landscape and the threat from terrorism changes.

The IRTL is required by section 36 of the Terrorism Act 2006 (TACT 2006) to report annually on the operation of Part 1 of that Act and the Terrorism Act 2000. Beyond this, he has discretion to set his work programme and can also review a range of other Acts depending on where he feels he should focus his attention, or if requested to do so by the Home Secretary or the Economic Secretary. The full remit of the IRTL includes:

- Terrorism Act 2000;

- Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (Part 1, and Part 2 in so far as it relates to counter-terrorism);

- Part 1 of the TACT 2006;

- Counter-Terrorism Act 2008;

- Terrorist Asset-Freezing Act 2010;

- Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011;

- Part 1 of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015; and

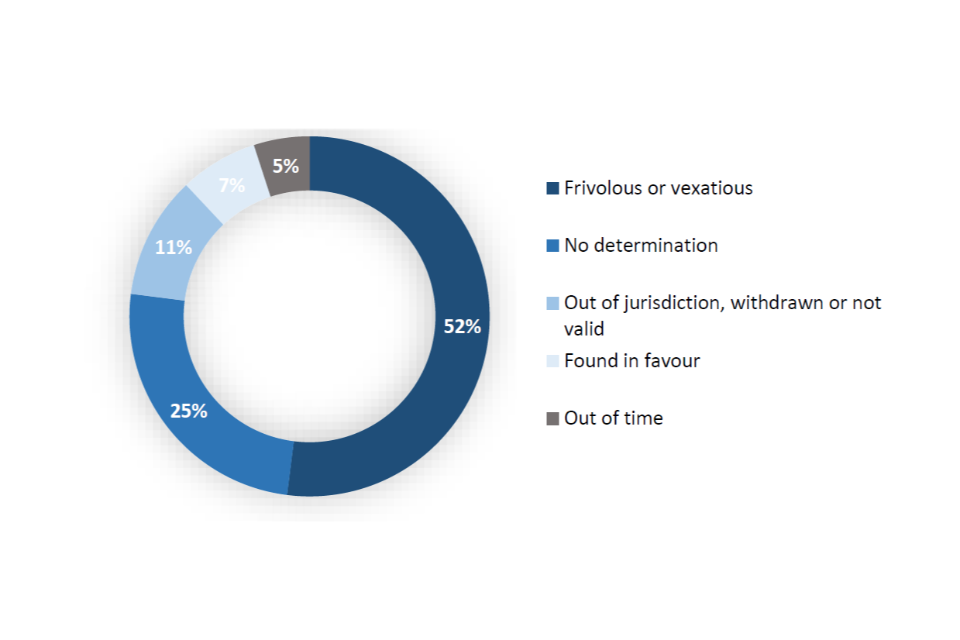

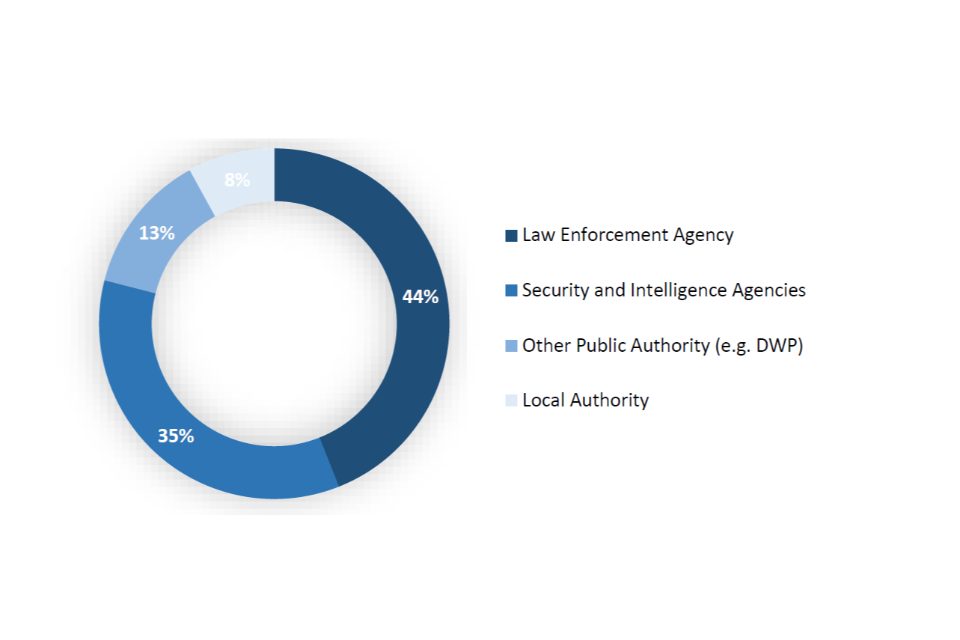

- Regulations made under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 with a counter-terrorism purpose.