Enteric fever (typhoid and paratyphoid) England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2022

Updated 22 August 2024

Applies to England, Northern Ireland and Wales

Enteric fever (also known as typhoid and paratyphoid) is an illness caused by the bacteria Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi (typhoid) or serovars Paratyphi A, B or C (paratyphoid). Typhoid fever is a serious disease and can be life-threatening unless treated promptly with antibiotics. The disease may last several weeks, and convalescence takes some time. In the literature, paratyphoid is considered to be typically milder than typhoid and of shorter duration (1, 2).

The bacteria that cause typhoid and paratyphoid only occur in humans. Humans acquire infection through eating food or drinking water that has been contaminated with infected faeces or through direct faecal-oral transmission. Transmission occurs following the ingestion of food or water that has been heavily contaminated (10 or more organisms may be required to cause illness) by the bacterium S. Typhi or S. Paratyphi. In the UK, most cases of typhoid and paratyphoid are acquired abroad in countries and regions of the world where hygiene or sanitation is poor.

This report summarises the epidemiology of laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi reported in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (EWNI) in 2022. It includes both reference laboratory and enhanced enteric fever surveillance data. Additional summaries of asymptomatic, probable and possible cases for England are presented at the end of this report.

Case definitions

Typhoid and paratyphoid case definitions (3).

Confirmed case

A confirmed case is defined as an individual who has S. Typhi or S. Paratyphi infection confirmed by the UKHSA (UK Health Security Agency) Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU) Salmonella Reference Service (SRS) [footnote 1].

Probable case

A probable case is defined as an individual who either:

- has a local laboratory presumptive (locally confirmed) identification of Salmonella Typhi (S. Typhi) or S. Paratyphi on faecal and/or blood culture, or culture of another sterile site (for example, urine), with or without clinical history compatible with typhoid/paratyphoid

- is a returning traveller giving a clinical history compatible with typhoid/paratyphoid and documentation of a positive blood/faecal culture (or positive PCR for S. Typhi / S. Paratyphi on blood)

Possible case

A possible case is defined as an individual who either:

- has a clinical history compatible with typhoid/paratyphoid and where the clinician suspects typhoid/paratyphoid is the most likely diagnosis

- has a clinical history of fever and malaise and/or gastrointestinal symptoms compatible with typhoid/paratyphoid and an epidemiological link such as contact with a case or a source of typhoid/paratyphoid, for example, from ‘warn and inform’ information

- is a returning traveller reporting a diagnosis made abroad with salmonella PCR from faeces but no documented evidence of a positive blood or faecal culture for typhoid or paratyphoid

Data sources

Confirmed symptomatic cases of S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are diagnosed by the UKHSA Salmonella Reference Service (SRS), within the Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU). Data for laboratory-confirmed cases from 2007 onwards were extracted from the reference laboratory database using the ‘date received by the laboratory’.

All S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi isolates referred to the SRS undergo identification using whole genome sequencing (WGS) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) typing (4, 5).

Cases are occasionally tested multiple times for confirmation and to check the infection has cleared, therefore data has been deduplicated so that only one laboratory report for each case is counted.

Epidemiological information was obtained from enhanced enteric fever surveillance (6). For England cases, additional details were sourced from the UKHSA case management system (HPZone), while Wales and Northern Ireland provided surveillance information directly for their respective cases.

All data was analysed using Excel for Office 365 (Version 2208, Microsoft).

General trend

Data on travel to and from the UK, obtained from the ONS International Passenger Survey, represents the most up to date travel data currently available.

In 2022, UK residents made 71.0 million visits abroad, a four-fold increase compared to 2021 (19.1 million). There were 31.2 million visits made by overseas residents to the UK, a five-fold increase compared to 2021 (6.4 million) (7). These increases can be attributed to the easing of COVID-19 travel restrictions at the end of 2021. However, travel to and from the UK in 2022 still remained below the pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels of 2019 (8). For both UK visits abroad and overseas visits to the UK in 2022, seasonality of travel returned to pre-COVID-19 patterns, with most travel occurring during the summer months of June, July and August, reaching its peak in August 2022 (7).

The most popular reasons for travel by UK residents in 2022 were holidays, with 45.6 million visits, followed by visiting friends and relatives (19.0 million) and business travel (4.8 million). The top 5 most visited countries were Spain, France, Italy, Greece and Portugal (7).

Holiday travel was also the most popular reason for overseas residents visiting the UK in 2022, with 12.1 million visits, followed by visiting friends and relatives (11.8 million) and business travel (5.1 million). This is a change compared to 2021 when visiting friends and relatives was the most popular reason for travel to the UK. Residents of the USA, France, Republic of Ireland, Germany and Spain represented the highest numbers of overseas residents visiting the UK (7).

In 2022, 470 laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi infection were reported by the UKHSA SRS in EWNI, a significant increase of 209% compared to the 108 cases reported in 2021 (see Table 1 and Figure 1). This is the largest annual increase in cases observed since 1980 (9, 10, 11) coinciding with the increase in overseas travel by UK residents after the lifting of COVID-19-related travel restrictions. Of these cases, 67% were caused by S. Typhi, 29% by S. Paratyphi A and 4% by S. Paratyphi B (see Table 1). There were 4 additional cases of mixed infection (cases co-infected with both S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi). Notably, one of these cases was infected with S. Typhi, S. Paratyphi A and S. Paratyphi B. No cases of S. Paratyphi C were reported in 2022.

Table 1. Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of enteric fever, England, Wales and Northern Ireland by organism: 2013 to 2022

| Year | S. Typhi | S. Paratyphi A | S. Paratyphi B | S. Paratyphi C | Mixed infection | Total | % S. Typhi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 181 | 121 | 5 | - | - | 307 | 59% |

| 2014 | 185 | 113 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 310 | 60% |

| 2015 | 168 | 108 | 26 | - | - | 302 | 56% |

| 2016 | 172 | 133 | 8 | - | - | 313 | 55% |

| 2017 | 187 | 103 | 15 | - | - | 305 | 61% |

| 2018 | 205 | 126 | 19 | - | - | 350 | 59% |

| 2019 | 321 | 166 | 19 | 1 | - | 507 | 63% |

| 2020 | 127 | 57 | 6 | - | - | 190 | 67% |

| 2021 | 108 | 31 | 13 | - | - | 152 | 71% |

| 2022 | 313 | 135 | 18 | - | 4 | 470 | 67% |

Figure 1. Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi, with % change year to year, England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2013 to 2022

Age and sex

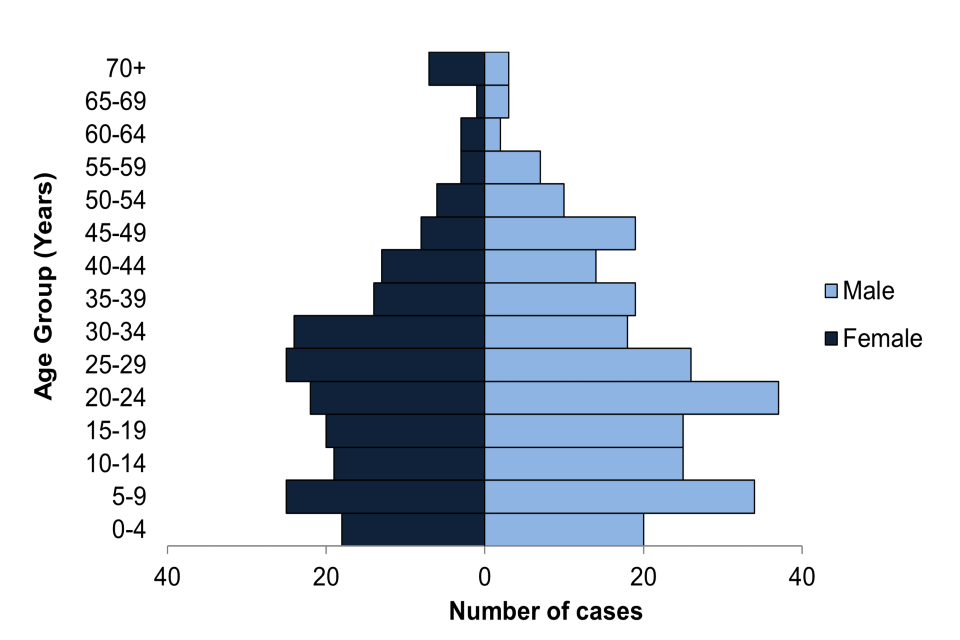

In 2022, age and sex were known for all 470 confirmed symptomatic cases; 39% were adults between 20 and 39 years (see Figure 2); the median age was 24 years (range 1 to 84 years). Those under 15 years accounted for 30% of cases, with 1% (5 cases) of the total in children under 2 years (and thus not routinely eligible for vaccination). Overall, there were slightly more male (56%) than female cases.

Figure 2. Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of enteric fever, England, Wales and Northern Ireland by age and sex where sex is known: 2022 (total 470 cases)

Geographical distribution

Geographical areas were assigned based on patient postcode; in a small number of cases patient postcode was missing and the sending laboratory postcode was used. In 2022, the largest proportion of cases of S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi in England were reported in London (34%), a slight decrease compared to the previous year (35% in 2021) (see Table 2). All regions across England, Wales and Northern Ireland saw a significant increase in cases compared to the previous year. However, these changes are difficult to interpret due to the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021.

Table 2. Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi, England, Wales and Northern Ireland by geographical distribution: 2021 and 2022

| Geographical area (UKHSA) | 2021 | 2022 | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | 54 | 160 | 196% |

| West Midlands | 18 | 63 | 250% |

| North West | 24 | 50 | 108% |

| South East | 17 | 55 | 224% |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 17 | 38 | 124% |

| East of England | 11 | 35 | 218% |

| East Midlands | 7 | 35 | 400% |

| North East | 1 | 12 | 1100% |

| South West | 1 | 11 | 1000% |

| England Total | 150 | 459 | 206% |

| Wales | 2 | 8 | 300% |

| Northern Ireland | 0 | 3 | N/A |

| EWNI Total | 152 | 470 | 209% |

Disease presentation and outcomes

In 2022, symptom information was known for 99% (466 out of 470) of laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of enteric fever. Hospital admission data was available for 467 cases, with 401 (85%) requiring hospitalisation due to their illness. Additionally, where data was available, 76% (278 out of 366) cases reported absence from work or school as a result of their illness.

The most common symptom for all cases combined was fever, with 94% of S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi A cases, 78% of S. Paratyphi cases, and was reported in all cases of mixed infections. Diarrhoea was the second most frequent symptom, present in 66% in S. Typhi cases, 58% in S. Paratyphi A cases, 78% in S. Paratyphi cases, and reported in all mixed infection cases. Vomiting was a frequently reported symptom in S. Typhi cases (41%). Headache was a frequently reported symptom in S. Paratyphi A cases (44%) and in cases of mixed infections 75%).

A high proportion of enteric fever cases required hospitalisation as a result of their illness, with 89% of S. Typhi, 82% of S. Paratyphi A, 61% of S. Paratyphi B, and all mixed infection cases requiring medical care.

Where data was available, 58% of S. Typhi cases, 64% of S. Paratyphi A cases, 39% of Paratyphi B cases, and all mixed infection cases reported missing work or school as a consequence of their illness.

Travel history

In 2022, 99.6% (468 out of 470) of laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi had travel history information recorded (that is, whether they had travelled abroad or not) (see Figure 3). Of these, 96% (448 out of 468) reported onset of illness within 28-days of travel to an endemic region of the world (and therefore were presumed to have acquired the infection abroad) (see Figure 4). This represents an increase from 87% in 2021. Of cases in 2022, 94% (419 out of 448) were UK residents who had travelled abroad from EWNI, while the remainder were either new entrants (23 cases, 5%) or foreign visitors (6 cases, 1%) to EWNI. For 20 cases no foreign travel was reported in the 28 days prior to becoming symptomatic).

Figure 3. Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of enteric fever, England, Wales and Northern Ireland by travel history: 2013 to 2022

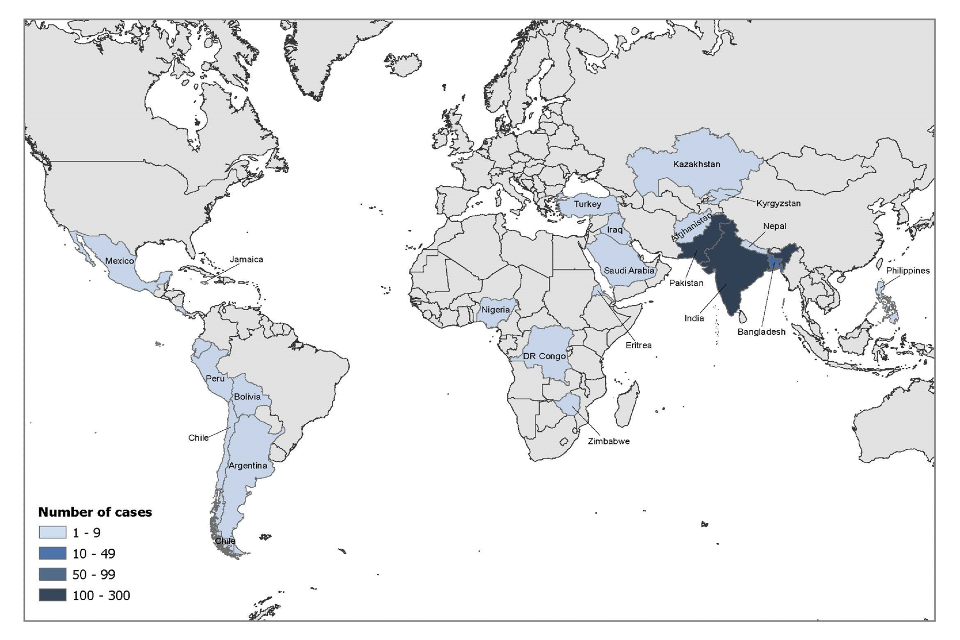

Figure 4. Presumed country of infection for laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of enteric fever that travelled abroad from England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2022 (total 419 cases)

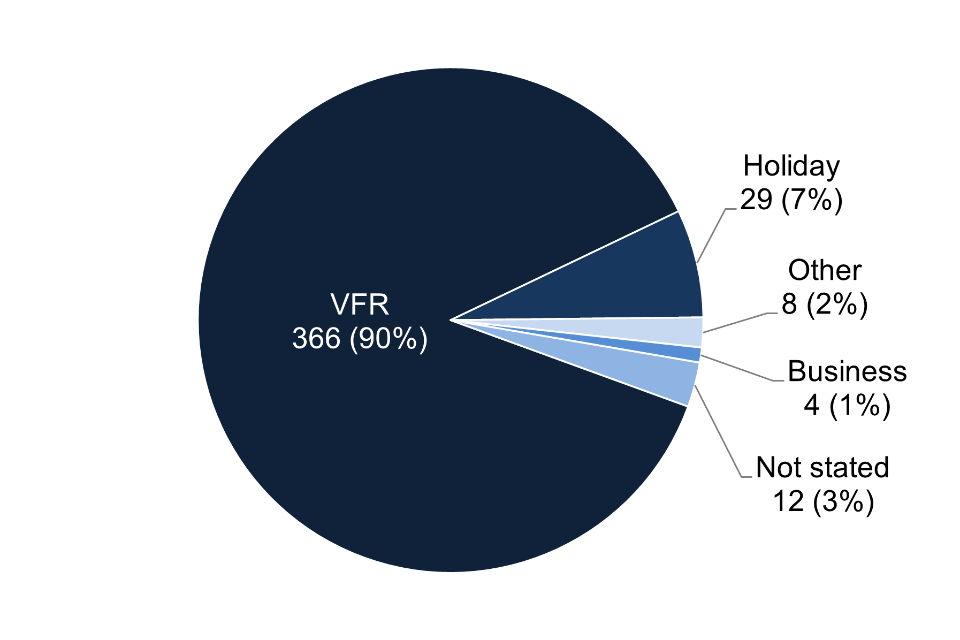

Where reason for travel was documented (407 cases), 90% of cases travelled abroad from EWNI to visit friends and relatives (VFR) (366 out of 407) (Figure 5). The majority travelled to countries in Southern Asia (Table 3) and acquired the infection while visiting friends or relatives abroad in Pakistan and India. Ethnicity was not known for 16 cases that travelled abroad to visit friends and relatives, these individuals travelled to Pakistan (12), India (2), Afghanistan (one) and Turkey (one).

For those UK resident cases who did not visit friends and relatives (41 cases), where reason for travel was known this included holidays (29), business (4) and other, such as studying abroad (8). These cases travelled to a number of countries, including Pakistan (17), India (8), Bangladesh (3), and countries in the Americas (8), Asia (4) and Africa (one).

For the 12 cases where reason for travel was not stated, 8 travelled to Pakistan, 2 to India, one to Mexico, and one case travelled to Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Chile.

Figure 5. Reason for travel for laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of enteric fever that travelled abroad from England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2022 (total 419 cases)

Table 3. Country of travel and ethnicity for laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of enteric fever that travelled abroad from England, Wales and Northern Ireland to visit friends and relatives: 2022 (a total of 367 cases, see note 1)

| Presumed country of infection | Pakistani | Indian | Bangladeshi | Asian other | Black African | Black Caribbean | White British | Other/mixed | Ethnicity not stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | 168 | 1 | - | 3 | - | - | 1 | 5 | 12 | 190 |

| India | - | 121 | - | 3 | - | - | 5 | 2 | 131 | |

| Bangladesh | - | - | 27 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 28 |

| Other Asia | - | - | - | 5 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Africa | - | - | - | - | 6 | 1 | - | - | - | 7 |

| Americas | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Total | 168 | 122 | 27 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 14 | 16 | 367 |

Note 1: some cases travelled to more than one country; all countries are included here so the totals will be higher than the actual number of cases

Clusters

Whole genome sequencing, carried out for all S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi cases, identifies clusters based on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Those described here are 5-SNP clusters, which indicate closely genetically linked organisms. Due to the low mutation rate of typhoidal salmonella and the recognition of specific clones circulating endemic countries, strains within the same 5 SNP cluster can indicate potential source of travel (12).

S. Typhi

In 2022, a total of 41 clusters of S. Typhi were identified, the largest of these, cluster t5.1, consisted of 79 cases, accounting for 25% (79 out of 317) of all laboratory-confirmed symptomatic cases of S. Typhi. Within this cluster, 91% (72 cases) reported travel history to Pakistan, mainly to Karachi and Lahore. In addition, 41 cases in this cluster were linked to an ongoing outbreak of an extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strain of S. Typhi first identified in 2016 in Sindh province, Pakistan. This strain is resistant to most antibiotics used to treat enteric fever, including ampicillin, chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole (which confers multidrug-resistant (MDR) S. Typhi), fluoroquinolones and third generation cephalosporins (bla CTX-M-15 extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producers) (13, 14). Since 2019, the XDR strain has been found circulating in other areas of Pakistan and is no longer restricted to the Sindh province (14, 15). Following a peak of 34 cases in 2019 (12, 13), the number of imported XDR S. Typhi within this cluster decreased in the subsequent two years during the COVID-19 pandemic, then increased to 41 cases in 2022. Since 2020, the XDR cases have been identified as part of a 5-SNP cluster, indicating expose to a common source of infection (3). Of the cases identified in 2022, all had travel history to Pakistan. See clinical guidance for the management of these extensively drug-resistant cases. The second largest S. Typhi cluster, t5.355, consisted of 23 cases reported in 2022, all reporting travel to India, particularly the Punjab region in the north. This cluster was first identified in 2017, with 52 cases in total, all with history of travel to India.

S. Paratyphi A

For S. Paratyphi A, 16 clusters were identified in 2022. The largest cluster, t5.49, consisting of 18 cases in 2022, has had 52 cases since it was first identified in 2014. All cases had travelled to Pakistan except for one case who travelled to Saudi Arabia and one case with no travel reported in 2019.

The second largest S. Paratyphi A cluster in 2022, t5.17, consisted of 14 cases. This cluster was first identified in 2015 with 38 cases in total. The majority of cases had travelled to Pakistan (34 cases), except for one case who did not travel in 2015 and three cases in 2022 who travelled to Saudi Arabia.

S. Paratyphi B

For S. Paratyphi B, 5 clusters were identified in 2022. The largest, t5.129, involving 5 cases, was linked with travel to the Americas: Bolivia (three), Costa Rica (one) and Argentina (one). This cluster, first identified in 2015, has been mainly linked to travel to South America, particularly Bolivia. In total, 13 cases have reported travel to Bolivia out of the 21 cases reported. One case in 2015 and three cases in 2018 had no travel history reported.

The second largest S. Paratyphi B cluster in 2022, t5.141, consisted of 4 cases who reported travel to Iraq (2), Kazakhstan (one) and Kyrgyzstan (one). This cluster was first identified in 2015 (16) and has 21 cases overall, mainly associated with travel to Iraq (18 cases). There was one case with no travel history reported in 2018.

Non-travel-associated cases

In 2022, there were 20 cases classified as non-travel-associated cases, these were confirmed cases of symptomatic enteric fever where the case reported that they did not travel in the 28 days prior to becoming symptomatic. 13 were caused by S. Typhi, 5 were caused by S. Paratyphi A and 2 were caused by S. Paratyphi B.

S. Typhi

Of the 13 non-travel-associated cases caused by S. Typhi:

- Three cases had household contacts who had recently returned from an endemic country. Two of these cases were in the same household and part of a 5-SNP cluster first identified in 2018, mainly associated with travel to Pakistan. The third case was part of a separate cluster linked to a household member who travelled to India in 2022

- Five cases had been in contact with a family member or a friend who had recently returned from an endemic country. Two of these cases were part of a 5-SNP cluster linked with travel to Nigeria, first identified in 2015. Another case was part of a cluster linked to travel to Pakistan, first identified in 2018. Another case was part of a cluster linked to a case who travelled to Pakistan in 2022

- No potential sources of infection were identified for the remaining five cases

S. Paratyphi A

Of the 5 non-travel-associated cases caused by S. Paratyphi A:

- One case had a household contact who had recently returned from an endemic country. This case was part of a 5-SNP cluster linked to travel to Pakistan, first identified in 2017

- One case had contact with a family member or a friend who had recently returned from an endemic country. This case was part of a 5-SNP cluster linked to travel to Pakistan, first identified 2018

- No potential sources of infection were identified for the remaining three cases

S. Paratyphi B

No potential sources of infection were identified for either of the two S. Paratyphi B cases.

Confirmed asymptomatic cases

In 2022, there were 3 confirmed asymptomatic cases of enteric fever caused by S. Paratyphi A (one case) and S. Paratyphi B (two cases). Of these, one case travelled to Pakistan and was identified as part of a 5-SNP cluster, while another case travelled to Eritrea and was identified as part of a separate 5-SNP cluster. Both cases were identified through contact tracing as household contacts and co-travellers of known symptomatic cases. The remaining case, a non-travel-associated case, had been admitted to hospital for unrelated condition, prompting consideration of enteric fever. This case had previous extensive travel and absence of recent travel suggesting possible carriage. A possible carrier is defined as a person with no recent history of travel or a relevant medical history but may have lived in or travelled extensively to endemic regions (6).

Probable and possible cases

In 2022, there were 7 probable and 6 possible cases of enteric fever as defined in the UK Health Security Agency Public Health Operational Guidelines for Typhoid and Paratyphoid (Enteric Fever) (6). Of these, 12 had travelled abroad from EWNI and the remaining case did not travel abroad. Travel history information for the probable and possible cases is detailed below in Table 5. Caution should be used when interpreting this data as it has not been confirmed by the UKHSA reference laboratory.

Table 4. Country of travel and reason for travel for probable and possible cases of enteric fever that travelled abroad from England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2022 (total 12 cases)

| World region of travel | VFR | Holiday | Business | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 3 | 2 | - | 5 |

| Pakistan | 3 | - | - | 3 |

| Bangladesh | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Sierra Leone | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Thailand | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Uganda | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 9 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

Information resources

NaTHNaC typhoid and paratyphoid fact sheet

NaTHNaC food and water hygiene advice

UKHSA typhoid and paratyphoid page

Typhoid: health advice for travellers (Asian languages)

Travelling overseas to visit friends and relatives – health advice

Gastrointestinal bacteria reference unit – reference and diagnostic services

References

- Cook GC and Zumla A. ‘Manson’s tropical diseases’ Elsevier Health Sciences 2009

- Heymann DL. ‘Control of communicable diseases manual’ American Public Health Association 2008

- UK Health Security Agency. Public health operational guidelines for typhoid and paratyphoid (enteric fever)

- Chattaway MA and others. ‘The Transformation of Reference Microbiology Methods and Surveillance for Salmonella With the Use of Whole Genome Sequencing in England and Wales’ Frontiers in Public Health 2019, volume 7, page 317. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00317

- Dallman, TJ and other. ‘SnapperDB: A database solution for routine sequencing analysis of bacterial isolates’ bioRxiv 189118, doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/189118

- UK Health Security Agency. Typhoid and paratyphoid: guidance, data and analysis. Health Protection Collection

- Office for National Statistics. ‘Travel trends: 2022’

- Office for National Statistics. ‘Coronavirus and the impact on the UK travel and tourism industry’

- Health Protection Agency. ‘Salmonella Typhi & Salmonella Paratyphi. Laboratory reports (cases only). England and Wales, 1980 - 2005’

- Public Health England. ‘Typhoid and paratyphoid: laboratory confirmed cases in England, Wales and Northern Ireland’

- UK Health Security Agency. ‘Typhoid and paratyphoid: laboratory confirmed cases in England, Wales and Northern Ireland’

- Chattaway MA, and others. ‘Phylogenomics and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella Typhi and Paratyphi A, B and C in England, 2016-2019’ Microbial Genomics 2021, volume 7, issue 8, 000633.

- Nair S, and others. ‘ESBL-producing strains isolated from imported cases of enteric fever in England and Wales reveal multiple chromosomal integrations of blaCTX-M-15 in XDR Salmonella Typhi’. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2021, volume 76, issue 6, pages 1459-1466.

- World Health Organisation Disease Outbreak News Item. ‘Typhoid fever - Islamic Republic of Pakistan’

- Rasheed F and others. ‘Emergence of Resistance to Fluoroquinolones and Third-Generation Cephalosporins in Salmonella Typhi in Lahore, Pakistan’ Microorganisms 2020, volume 8, page 1336. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8091336

- Chattaway MA and others. ‘Genomic sentinel surveillance: Salmonella Paratyphi B outbreak in travellers coinciding with a mass gathering in Iraq’ Microbial Genomics 2023, volume 9. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000940

-

As we only collect data from the UKHSA Salmonella Reference Service, local reports of cases of enteric fever may differ for Wales and Northern Ireland. ↩