UK Pesticides National Action Plan 2025: Working for a more sustainable future

Updated 24 October 2025

This National Action Plan (NAP) is framed against our statutory obligations in pesticides regulation. It has been developed in partnership between the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government, and the Northern Ireland Executive (collectively referred to in this document as ‘we’ or ‘our’ or the ‘4 governments’), and applies to the whole of the United Kingdom. It is also in conformance with the Chemicals and Pesticides Provisional Common Framework which formalises ways of working between the 4 governments on pesticides policy.

Pesticides, and wider environmental policy, are devolved to each government. This means different decisions can be taken in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and different policies can be followed. Whilst respecting the statutory and executive freedoms of the individual administrations to take different policy approaches and make different decisions, all 4 governments, along with the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) as the regulator acting on behalf of all parts of the UK, seek consistency of decision-making where this is appropriate and desirable.

Introduction

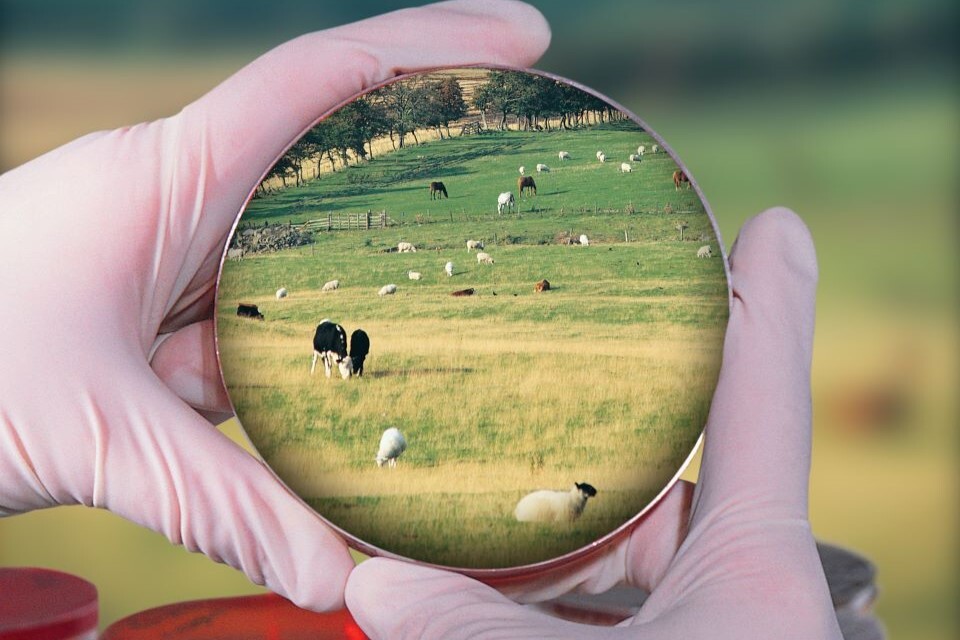

In a world where food security, nature recovery and environmental sustainability are increasingly intertwined, the responsible use of pesticides, also known as plant protection products (PPPs), is pivotal to maintaining the delicate balance.

Pesticides play an important role in protecting crops to support domestic food production, preserving natural landscapes, and maintaining vital public spaces, such as road, rail networks, and sports pitches.

However, overuse or incorrect use of pesticides can contribute to biodiversity loss and unacceptable human exposure levels. Prolonged use of pesticides can also lead to pesticide resistance as has been identified in the case of black-grass herbicides (Varah A and others, 2020).

We are committed to reducing the risks of pesticide use. The National Action Plan (NAP) sets out the strategy for managing pesticide use and minimising risk. It reflects the priorities and ambitions of all 4 governments in the UK and aims to promote the sustainable use of pesticides to minimise impacts on the environment and human health, whilst managing pests and pesticide resistance effectively and ensuring farmers have the tools they need for food production.

This NAP focusses on our actions against our statutory obligations (see Annex 1), and covers:

- encouraging the development and uptake of integrated pest management (IPM) and alternative approaches or techniques to reduce dependency on the use of pesticides

- establishing timetables and targets for the reduction of the risks and impacts of pesticide use, including monitoring and setting targets for the reduction of use of pesticides containing active substances of particular concern

- ensuring storage, handling, cleaning and disposal operations do not endanger human health or the environment through effective inspection, enforcement and other official control activities

At the 15th meeting of the Conference of Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 15) in December 2022, a global target was set to reduce “the overall risk from pesticides and highly hazardous chemicals by at least half” by 2030, as part of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

The UK already performs well on pesticide usage relative to the rest of the world. Whilst the total weight of pesticide active substance applied in agriculture increased globally by around 90% between 1990 and 2020, the UK saw a near 60% decrease over the same period (see Annex 3 for further detail).

However, to contribute even further to the global target, this NAP introduces a domestic reduction target for pesticides in the UK. The target is based on the UK Pesticide Load Indicator (PLI), which combines data on pesticide usage with information on pesticide properties (hazard and environmental behaviour) to illustrate and track trends in the potential pressure that pesticides are placing on the environment. The PLI consists of 20 metrics that cover the potential harm pesticides pose to different indicator species (for example, how toxic they are to bees) and their behaviour in the environment (for example, how long they persist). We are setting a target of reducing each of the 20 metrics of the PLI by at least 10% by 2030, using 2018 as a baseline year. Achieving the target will demonstrate that the actions we are taking are reducing the potential impact associated with pesticide use.

We are determined to explore how we can go further in reducing our use of pesticides across all sectors and achieve continuous improvement against our indicators whilst supporting sustainable crop production and amenity management. This will mean regular review of progress, and collaboration with pesticide users and consumers to identify where there may be future opportunities.

We will also consider ways in which we can improve the regulatory system so that it works as effectively and efficiently as possible, provides greater clarity and predictability and better supports availability of crop protection options for food production. Any changes to the regulatory system in the future in Northern Ireland, will take into account the Windsor Framework.

This is the start of a new and ambitious journey. We intend to supplement the NAP with further detail that will outline our emerging priorities and provide a more comprehensive framework for achieving our vision for pesticides going forward.

Objective 1: Encourage uptake of Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

Farmers, growers, foresters and amenity managers need a diverse range of pest management solutions to support sustainable food production and management of amenity areas. Over-reliance on individual products is a driver of pesticide resistance, which could reduce the availability of effective active substances for tackling pest problems over time.

IPM is a holistic and sustainable approach which makes use of a range of methods, and promotes preventative measures, to keep the use of conventional chemical pesticides to levels that are ecologically and economically justified, minimising risks and impacts to human health and the environment (see Annex 2 for further information).

In farming, preventative measures can reduce the risk of pests becoming established or reaching dangerous levels, and can include:

- crop rotation

- cultivation and tillage practices (how the land is prepared to grow crops)

- growing pest-resistant varieties

- hygiene measures (such as regular cleansing of machinery and equipment)

- encouraging natural predators

IPM approaches also include using precision application technologies for targeted application of chemical pesticides where needed, when alternative methods are ineffective or unavailable.

IPM aligns with the concepts of circular economy and sustainable resource consumption. It reduces reliance on the use of chemical pesticides by managing the risk of pest damage, making use of alternatives, for example, biological or physical control and promoting natural processes. It can have significant benefits in reducing pressures on biodiversity and the environment. When applied as part of a longer-term, whole farm management approach, several IPM techniques have been shown to improve natural capital, including soil health and water quality, leading to increased abundance and diversity of beneficial insects and other non-target species, which are vital to improving sustainability of ecosystems and protecting food security. IPM has also been shown to support the resilience, health, and productivity of crops, therefore, helping to maintain and enhance yield and reduce input costs (He and others, 2016).

Most farmers and growers are already using IPM practices, but the extent may depend on crop sector, farm size and sources of advice, as these IPM uptake case studies highlight. Evidence shows that some farmers consider IPM as a higher-risk approach to protecting their crops, which could potentially compromise economic return, and perceptions of financial risks can be barriers to IPM uptake. Defra has set up IPM NET, in collaboration with ADAS, which is a network of farmers using IPM. Both agronomic and economic data are being collected from these farms to try and understand any financial impacts.

For more information, see the review of evidence on IPM.

IPM research and development projects

All 4 governments already support a broad range of IPM research and development projects across the UK.

In England, Defra’s Plant Health Research and Development programme has supported several research projects prioritising IPM and alternative pest control management methods, particularly those using nature-based solutions. The Forestry Commission has also supported multiple projects through the Tree Production Innovation Fund (TPIF) and Woods into Management Forestry Innovation Funds (WiMFIF), for example, the ‘Autonomous Smart Spot-Precision Application of Herbicide’, and the ‘Will earwigs predate green spruce aphid over winter to provide early season control?’ projects.

Forest Research (a part of the Forestry Commission) is undertaking research that aims to enhance the use of IPM approaches in UK forestry, and research into direct reduction of pesticide use in the sector.

Defra, in partnership with Innovate UK, has committed over £127 million through the Farming Innovation Programme (FIP) for industry-led research and development in agriculture and horticulture. This programme aims to drive innovation that will transform the productivity, profitability, and environmental sustainability of farming in England. Examples of projects funded through FIP include designing and testing robotic weeders to remove black-grass and developing slug resistant wheat.

In Wales, Defra and the Welsh Government have funded projects through the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI), trialling the use of biocontrol to manage invasive plants, for example, using rust fungus to control Himalayan balsam (Pollard and others, 2021).

In Scotland, the Plant Health Centre aims to improve resilience to plant health threats by connecting science to applied research to inform policy, planning responses and solutions. It has undertaken a range of IPM-related projects, including, for example, perceptions of pest risk and differences in IPM uptake by arable farmers and agronomists (Creissen and others, 2021). It also maintains IPM plan templates available for use by Scottish businesses. The recently refreshed IPM plans for Scottish growers improve on the previous version by allowing growers’ progress in adopting IPM to be measured.

In Northern Ireland, collaboration between the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI), DAERA, and the College of Agriculture, Food and Rural Enterprise (CAFRE) has led to the development of a monitoring network for aphids, which can severely damage potato and cereal crops. The results of this monitoring, published weekly on the AFBI webpage and shared through social media, provide an easily accessible decision-making tool, with some growers already reporting economic savings through reduced insecticide use.

Supporting IPM uptake in agriculture and horticulture

We are committed to supporting all pesticide users to fully embrace IPM approaches. In England, there are currently 4 IPM actions and 3 pesticides precision application actions available within the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) scheme. The scheme pays farmers to adopt and maintain sustainable farming practices that can protect and improve the environment. The SFI actions for IPM are focused on increasing knowledge and identifying opportunities for an IPM approach, for example:

- creating habitats for natural crop pest predators

- using companion cropping for suppressing weeds, reducing diseases and providing protection from crop pests

- minimising use of insecticides

The Welsh Government is in the process of developing agri-environment schemes to replace previous EU-wide schemes. These schemes will likely include measures to support the uptake of IPM actions.

In Scotland, the Agricultural Reform Programme will transform how we support farming and food production to deliver the Vision for Agriculture and become a global leader in sustainable and regenerative agriculture.

Work is also underway across the UK to encourage and support the uptake of IPM through provision of information. For example, each government has published a toolkit of useful IPM resources on their respective websites. This aims to support farmers and growers by providing information on IPM approaches that work, creating an IPM plan and using decision support systems to manage and respond to different pest, weed and disease pressures. Defra has also worked with ADAS to develop a series of videos which provide in-depth knowledge of IPM theory and practice to support farmers, growers and agronomists. These videos are available to farmers across the UK.

Case studies: IPM in agriculture

Nonington Farm, James Loder-Symonds

Farmer and agronomist James Loder-Symonds has found that by using preventative and natural pest management, he has been able to work without insecticides on his farm for the last 4 years.

He has adopted techniques like habitat creation for beneficial insects, using barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) resistant varieties, reducing soil disturbance, extending rotations and cover and companion cropping. Where chemical inputs are needed, precision spraying through Global Positioning Satellite-linked machinery has increased efficiency. As a result, his variable costs on winter wheat have been reduced by around £200 per hectare without any drops in yield and quality for harvest from 2020 to 2022. James expects his costs to fall further as crop and soil health continue to improve, and for farm profitability to be more consistent year on year.

400-hectare arable farm, managed by J Llewellin & Co

The Llewellin family has farmed Trewarren since 1955. The introduction of IPM has allowed the Llewellin family to grow crops productively and profitably while improving soil health and the natural environment – with crop yields maintained, or in the case of oilseed rape, increased.

Three-quarters of Trewarren Farm is used for arable crop production, including wheat, winter oilseed rape and beans. The IPM practices introduced on the farm include cover cropping, reduced tillage and crop rotation to support beneficial insects, and break pest, weed and disease cycles. Pest monitoring and GPS technology are used to ensure chemical inputs are targeted and proportionate, with insecticides only used when pest populations exceed thresholds.

The farm has seen a significant improvement in soil health since IPM techniques were introduced, which has, in turn, had a dramatic effect on populations of birds and beneficial insects. A recent count of ladybirds revealed 5 different species, and a butterfly count identified 12 different kinds. Because the soil is disturbed as little as possible, populations of deep burrowing worms have increased, and the soil’s water filtration properties have improved. The family has also planted hedges and ponds for irrigation and to provide habitats for wildlife and pollinators.

Science and technology underpin many of the farm’s IPM practices. GPS technology has allowed the farm to reduce inputs and increase efficiency through automatic sprayer shut-off, and field mapping by soil type and nutrition means crops can be drilled using variable seed rates to get even plant establishment. The resistance scores of seed varieties are carefully considered, to minimise vulnerability to disease.

Apple Scab (Venturia) monitoring in Northern Ireland

The combination of climate and the fact that the dominant apple cultivar grown in the region is Bramley, which is moderately susceptible to apple scab, means that it is considered the major disease that affects orchards in Northern Ireland. Apple scab infections occur during wetting periods when moisture stimulates the spores to germinate and penetrate plant tissue. Failure to control infections greatly depress yield and quality of apples produced, and as a result nearly 87% of all fungicides used by growers in NI are for scab control. Monitoring is carried out using Bukard volumetric spore traps.

To help growers maximise the efficacy of their spray programme, the College of Agriculture Food and Rural Enterprise (CAFRE) sends out alerts known as apple scab infection periods (ASIPs) to growers during periods of high disease pressure so that appropriate spray decisions can be made. These alerts are generated by the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) which has a research centre in Loughgall in County Armagh.

ASIPs are based on combination of a revised Mills table (scab prediction table used to determine whether conditions have been sufficient for infection) along with assessing the daily ascospore release from the data collected in a Bukard volumetric spore trap. The environmental data (leaf wetness and temperature) needed to calculate infection periods with the Mills table is collected on site at Loughgall.

The severity of infection can be estimated based on the numbers of spores counted on the slide and are categorised as light (less than 5 spores), medium (5 to 10 spores) and heavy scab pressure (more than 10 spores). Spore counts start on 17 March every year and continue until no more ascospores are generated. In Northern Ireland this is usually June, but depending on weather may continue well into July.

Supporting IPM uptake in the amenity and amateur sectors

Although many IPM measures were initially developed for agricultural and horticultural applications, it is a sustainable approach that can be applied to the amenity and amateur sectors and is also used in forestry.

The amenity sector is diverse, covering, for example:

- transport infrastructure

- sports pitches

- golf courses

- utility areas

- areas managed by local authorities, such as public parks and streets

We know that efficacy, availability of alternatives, public perception, safety and compliance with legal requirements all play a role in influencing pest, weed and disease management decisions in the amenity sector (Garthwaite and others, 2020).

We want to address some of the key barriers to IPM uptake in the amenity sector and reduce reliance on pesticides, whilst recognising the continuing role pesticides will play for example, in ensuring public highways are accessible and safe.

Those who work with professional pesticides must ensure that they have undertaken the relevant pesticide training or that they are supervised by someone who has, and that equipment is regularly tested and calibrated. To maintain good practice, it is important that organisations and individuals involved in the sector refresh their training. We want to encourage operators to regularly update their training and certification to include IPM elements. Membership of an assurance scheme can be a way of ensuring best practice is followed and industry standards are met.

Some pesticides are formulated and authorised for amateur use, for example, in home and community gardens, as well as allotments. The term IPM is likely to be unfamiliar to many members of the public. However, there is a level of interest which gives us scope to build upon the good work already being done by organisations such as the Royal Horticultural Society with their ‘Guide to controlling pests and diseases without chemicals’ and Dwr Cymru Welsh Water.

Case study: IPM in the amenity sector

Herbicide Reduction Plan, Cambridge City Council

Cambridge City Council implemented an IPM approach as part of its Herbicide Reduction Plan (HRP) following their declaration of a Biodiversity Emergency in 2019. This initiative aimed to minimise the use of herbicides in public spaces such as highway verges and pavements, seeking alternative methods to manage weeds.

The council’s strategy included establishing herbicide-free zones, starting with trial areas in Newnham and Arbury, and expanding to other wards. The trial explored the use of specialised street-cleaning mechanical equipment and hot foam treatments. Mechanical methods were particularly effective, reducing the need for herbicide applications. This resulted in a notable reduction in herbicide use, from 3 applications in 2021 to none in 2023.

The HRP emphasised community engagement through the ‘Happy Bee Street Scheme,’ fostering local involvement in maintaining herbicide-free areas. Feedback from stakeholders, including community groups and residents, played a vital role in refining the project. This IPM approach demonstrates how mechanical alternatives can effectively maintain urban green spaces while minimising environmental impact.

Scottish Local Authority Weed Control Survey, Scottish Government

The Scottish Government conducted a survey of Scottish local authority weed control activities during 2019. This was the first survey of its kind carried out in Scotland, and of the 32 local authorities contacted, herbicide use data was received from 27 and details of integrated weed management practices from 28.

All responding local authorities employed integrated control methods, adopting a combination of herbicide and non-chemical weed control strategies. The most commonly used non-chemical methods were mechanical control (for example, strimming, mowing, weed brushing and ripping), hand weeding and supressing weed growth with mulches.

A range of reasons for using non-chemical approaches were reported, with the main drivers being concern about environmental impacts and a desire to reduce operator and public exposure to herbicides.

Where herbicides were applied, all respondents stated that they took steps to reduce their use, primarily by evaluating whether there were alternative non-chemical control measures and by targeting herbicide use.

The surveyed local authorities collectively applied 15.2 tonnes of herbicide active substance in 2019. Eighty-six per cent of the responding authorities stated that they planned to continue to reduce the amount of herbicide applied in the future.

Role of innovation in IPM

As part of an IPM approach, new technologies can be used to prevent the need for conventional chemical control (for example, robotic weeding) or to ensure any necessary pesticide use is targeted (for example, using precision application technologies to minimise environmental risks) (Anastasiou and others, 2023). Precision application can also contribute to reducing input costs, as pesticide application is more efficient. In England, grant funding has been available for farmers and growers through the Farming Investment Fund to support purchase of capital items aimed at improving farming productivity, alongside environmental sustainability, such as precision farming and robotic solutions.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or drones, could enable better targeted application of pesticides, and replace hand-held equipment in some circumstances. The result could be environmental and health benefits from reduced pesticide use and economic benefits to farmers in terms of reduced input costs and the ability to treat land that is otherwise hard to reach.

The use of drones for this purpose is an emerging technology and is currently only allowed under restrictive permits.

We will work across departments and with stakeholders to understand fully the potential benefits and drawbacks of pesticide application by drone. We will consider whether changes to the current guidance and rules, for example, those which require permitting of individual spray operations, would help to realise the benefits.

Horizon scanning

We will develop an evidence-led UK horizon scanning capability, consulting with a range of experts, to ensure we have a proactive approach to understanding the potential impacts of any pest control gaps that arise due to the withdrawal of pesticides from the market. This will allow us to see where alternatives most need to be developed and to identify priority research and development areas. Horizon scanning would focus on those sectors most vulnerable to further loss of pesticides and will be used to explore possible management and mitigation options, including new technologies and alternative pest control options.

Development of lower risk biopesticides

Biopesticides include microbials (bacteria, fungi and viruses), semiochemicals (for example pheromones), plant-derived chemicals and other novel alternative products. Biopesticides are an area of growth – only 2 biopesticide active substances were approved in the UK in 1997, with that number increasing to 44 in 2020 – and with continued innovation we expect more novel biopesticides to emerge in the future.

Not all biopesticides are classified as low-risk, but of the 24 low-risk active substances currently approved in Great Britain, 20 are biopesticides. We want to improve their availability across a broader range of crops, therefore increasing the tools that can be used as part of an IPM approach to ensure an environmentally and economically sustainable future. Biopesticides can be complex to regulate, resulting in lengthy approval procedures that are a financial hurdle to smaller manufacturers.

Those applying for Great Britain approval currently benefit from the tailored advice and lowered fees in the existing Biopesticides Scheme. Northern Ireland is subject to EU approvals of active substances by virtue of the Windsor Framework and therefore is not covered by this scheme.

Case study: Biopesticides

Reducing dependence on synthetic fungicides in wheat production by using biologicals

Farmers and scientific experts joined forces to investigate the effectiveness of biological crop protection products as replacements, or supplements, to synthetic fungicides in wheat production in the North of England.

There is a growing concern that farmers will lose the tools they rely on to treat fungal pathogens in wheat crops due to increased pathogen resistance to conventional pesticides. The Farmer Scientist Network, supported by Yorkshire Agricultural Society, led a project to test different treatment strategies on several varieties of wheat over 3 years in 3 different northern UK locations. The locations were chosen to test the efficacy of biopesticides in diverse geographical areas.

Treatments consisted of conventional pesticides only, biopesticides only, or an IPM approach consisting of both biopesticides and conventional pesticides. They found that wheat can be produced using biopesticides, alone or in combination with conventional crop chemistry, while still obtaining similar yields and grain quality. To encourage knowledge transfer, open days were held at all 3 trial sites and results have been disseminated through various fora including the Association of Independent Crop Consultants annual conference and Farmers Weekly.

Actions to encourage uptake of IPM

Action 1

Increase awareness and knowledge of IPM strategies through the promotion of decision support and planning tools, practical guidance and access to learning and evidence from research and development.

Action 2

Work with farming advice services to improve the current IPM advice offer, so that it supports increased IPM uptake.

Action 3

Work with training providers to review the IPM offer to identify any gaps and areas of improvement to support IPM uptake.

Action 4

Explore opportunities for IPM facilitation funding for farmer, grower and forester led networks.

Action 5

Gather more data on IPM and pesticide usage in the amateur and amenity sectors to better understand use, how these contribute to overall pesticide load and potential IPM approaches.

Action 6

Review regulatory barriers to innovation, particularly around precision application technologies: explore the potential benefits and drawbacks of pesticide application by drones and consider whether rules and guidance need to be amended.

Action 7

Develop an internal evidence-based horizon scanning capability to identify, understand and mitigate pest control gaps.

Action 8

Continue to provide additional support to biopesticide applications.

Action 9

Consider how we can make improvements to the arrangements for GB biopesticides to reduce burdens without compromising environmental and human health standards.

Action 10

Continue to direct funding to facilitate applied research and development on priority areas where alternatives to conventional chemical pesticides are lacking, particularly in major crops.

Objective 2: Set clear targets and measures to monitor use of pesticides

We are setting a domestic reduction target for pesticides in the UK. Crucially, this is being done on the basis of potential environmental pressures rather than solely weight or volume applied. In setting a pesticides reduction target for the NAP, we want a target based on quantifiable outcomes, which is stretching, measurable, time bound and requires sustained action by all delivery partners.

Setting an ambitious target could act as a catalyst for innovation and improvement, for example, by promoting better practice. However, it is important to consider the achievability of targets and ensure we can monitor progress and be accountable, whilst maintaining the competitiveness of UK agriculture.

Our target takes account of the chemical properties of pesticides as well as the quantity used. Simply focusing on the quantity of pesticides applied (in weight) and the area they are applied over, ignores variation in the chemical properties of the active substances applied and their potential impacts on the environment. Such targets could risk creating unintended consequences: for example, a reduction in weight applied would not necessarily mean a reduction in risk, if lower-risk pesticides were replaced with higher-risk ones. We need metrics that provide a good indicator of the potential pressure that pesticides are placing on the environment, to identify and monitor the use of more hazardous pesticides and substances of particular concern. We are therefore proposing a target based on the UK Pesticide Load Indicator (PLI).

Pesticide Load Indicator (PLI)

Over the past 4 years, we have developed the first UK Pesticide Load Indicator (PLI). The PLI is a multi-component indicator, which combines data on pesticide usage with information on pesticide properties. The PLI considers:

- the harm pesticides could potentially cause to different species groups

- the way pesticides behave in the environment

- the quantity used

The PLI consists of 4 behaviour metrics and 16 potential harm metrics. These 20 metrics are designed around the standard regulatory tests for approval of active substances and are quantified according to a rigorous scientific methodology. The data used to calculate the PLI comes from the UK Pesticide Usage Survey (PUS) and the Pesticide Properties Database (PPDB).

The PLI currently applies only to the agricultural arable sector, which accounts for around 90% of overall pesticide use in agriculture and horticulture. The PLI can therefore be reported on every 2 years based on the arable PUS cycle. We also have data on how pesticides are used on non-arable crops, but these are not currently incorporated into the PLI. We do not currently have robust data on usage in the amenity and amateur sectors. However, we will consider how we can secure more comprehensive information about the nature of pesticide use in these sectors to inform thinking about any further actions we can take to manage pesticide use and risk.

Potential harm metrics

The PLI considers the acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) toxicity of individual active substances to a range of organisms that are not the pesticide’s intended targets. These organisms represent groups such as invertebrates (including pollinators), birds, mammals and fish, and are listed below. The acute metrics focus on the dose or concentration of pesticide that causes death after short-term exposure. The chronic metrics focus on the dose or concentration of pesticide below which no harm is observed in each indicator species and are assessed using important measures of health such as growth and reproduction. The potential harm metrics are:

- fish (acute)

- fish (chronic)

- daphnia (acute)

- daphnia (chronic)

- algae (acute)

- aquatic plants (acute)

- mammals (acute)

- mammals (chronic)

- birds (acute)

- birds (chronic)

- earthworms (acute)

- earthworms (chronic)

- bees (contact acute)

- bees (oral acute)

- parasitic wasps (acute)

- predatory mites (acute)

Behaviour metrics

The PLI also considers how pesticides behave in the real world. Four additional metrics help to understand:

- how long a pesticide remains in the environment before it degrades

- how easily it moves into and through water and soil – and therefore how easily it could spread within the local environment

- a pesticide’s tendency to bioaccumulate or be taken up into plants or animals and stay in their tissue over extended periods of time

The behaviour metrics are:

- persistence (in soil)

- drain flow (surface water mobility)

- groundwater mobility

- bioconcentration factor

Quantity used

For each metric, the scores for every pesticide are combined with the quantity of that pesticide applied across the UK in a given year. These values are then summed to produce an overall score for each year assessed, which allows us to assess trends in the PLI metrics over time. In this way, we can measure how the potential pressure on the environment from pesticide use is shifting. The ability of the PLI to characterise these trends, and to link change to the contribution of specific active substances (and identify substances of concern), greatly enhances the ability to monitor the impact of policy actions.

Target level

In this NAP, we are setting a minimum domestic target to reduce each of the UK PLI metrics by at least 10% by 2030, taking figures for 2018 as a baseline. We have chosen 2018 as the baseline year for the target because this was a relatively typical year for pesticide usage, that provides at least a 10-year timespan over which to assess progress to 2030. We have avoided figures from 2020 as this was a year in which pesticide usage was substantially lower than all previous years, due mainly to challenging weather conditions affecting cropping patterns.

The target considers the individual metrics, rather than a single overall indicator of pesticide load. It ensures we are focused on driving action across the breadth of the metrics rather than, for example, making progress on reducing potential harm to fish but not paying attention to bees.

All 20 metrics are important. However, some will be much more challenging to achieve. Meeting the target will require action from all 4 governments, industry and land managers. It will necessitate a step change in the uptake of IPM, adoption of lower-risk alternatives and use of lower-risk pesticides, such as biopesticides.

It will be important to track progress towards our domestic target as this will provide assurance that we are doing everything we can to act responsibly and sustainably. Achieving this target will demonstrate that we are reducing potential environmental pressures associated with pesticide use.

We know that pesticide usage is driven by factors such as weather, which will impact the levels of different pests, weeds and diseases seen in a particular year. We will therefore be sure to present any point-to-point comparison between specific years in the context of overall trends.

Importantly, the target will be kept under review. We will be led by the evidence, and we will continually review progress against the target and consider whether it needs to be adjusted to ensure it continues to be ambitious. Given that Pesticide Usage Surveys are biennial and there can be a lag of up to one to 2 years in receiving the results, we are not likely to have sufficient data to track UK-wide progress until 2026.

For a detailed explanation of the Pesticides NAP target and how it will be achieved, read the ‘NAP target explainer’ document.

International targets

The domestic target will also contribute to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Target 7 agreed at COP15, to reduce the overall risks from pesticides and highly hazardous chemicals by at least half by 2030.

We have submitted to the Convention on Biological Diversity the UK targets which fully align with the goals and targets of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. These UK-wide targets commit us to meeting each of the global targets (including Target 7). We have published our National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) and will consider how all our domestic targets and actions contribute to these UK commitments.

Measuring progress

Alongside the headline target based on the Pesticide Load Indicator (PLI), we also plan to continue monitoring and reporting against a broader framework of:

- action-based indicators, for example uptake of IPM (number of plans completed), availability of biopesticides, and numbers of professional PPP users who have completed training

- outcome-based indicators, such as those covering pesticide usage, exposure, and risks to both the environment and human health. Trends in the use of substances presenting particular risks, including to human health, can be tracked through the Harmonised Risk Indicators (HRIs), which monitor trends in the sales and number of emergency authorisations of 4 categories of substances: low risk, standard risk, higher risk (candidates for substitution) and non-approved

We propose to maintain monitoring of the indicators used in the previous 2013 indicator framework to show how we are progressing against objectives within Directive 2009/128/EC on the sustainable use of pesticides (SUD), updating and expanding on these to clearly demonstrate progress. Further context will be provided through links to other relevant reports giving detail on how we identify priority issues that need to be addressed. We will align the indicators with the following objectives in the NAP:

- encouraging and supporting integrated pest management

- supporting compliance

Actions to set targets, measures and indicators to monitor progress

Action 11

Contact organisations responsible for collecting the underlying data behind the indicators included in the previous NAP to determine any potential to update, improve or replace the existing indicators.

Action 12

All 4 governments to hold discussions with internal and external partners, for example HSE and UK Environmental Regulators, to agree an indicator framework, and develop a plan for production of monitoring reports (on who will input, how they will be reviewed and quality assured).

Action 13

Assess progress against the target, reviewing the available evidence to assess whether the minimum target level should be adjusted to maintain a stretching level of ambition.

Action 14

Publish biennial reports on results of the indicator monitoring, including progress against the PLI target.

Objective 3: Strengthen compliance to ensure safety and better environmental outcomes

Legislation governing the sale and use of pesticides (the Plant Protection Products Regulations 2011, The Plant Protection Products Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2011, and the Plant Protection Products (Sustainable Use) Regulations 2012) is in place to ensure that anyone working with pesticides does so safely. We want to support awareness and understanding of these legal requirements to ensure good levels of compliance across all sectors.

Supporting best practice

Distributors and professional users of pesticides must take all reasonable precautions to ensure that their operations do not endanger human health or the environment. These are set out in the Codes of Practice for using pesticides (CoP), which are published by all 4 nations of the UK (see the CoP for England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland).

The CoP provides an important source of practical advice for those working in agriculture, amenity, horticulture and forestry sectors on how to use pesticides safely and, by doing so, meet the legal obligations which cover the use of pesticides. Additionally, the Code of Practice for suppliers of pesticides to agriculture, horticulture and forestry, provides practical guidance to suppliers of pesticides in Great Britain. The CoP also provides advice on how professional users can prevent pesticides from contaminating surface water and groundwater and therefore protecting drinking water.

Farmers are further supported through agri-environment schemes, and industry-led schemes. Government programmes such as Catchment Sensitive Farming also provide advice and access to grants to help protect the aquatic environment.

There are also protections built into the regulatory system when products are authorised so that pesticide users must follow conditions of use. For example, a product that can pose an unacceptable risk to the aquatic environment can still be authorised with the risk mitigation measure that it cannot be used within a certain distance of waterbodies.

Storage, handling and disposal

Professional users of pesticides must take all reasonable precautions to ensure that storage, handling, dilution, mixing, cleaning, and disposal operations do not endanger human health or the environment. Users must confine applications to target areas, use as low a frequency and amount as possible in certain areas, and may be required to meet additional requirements when working in or around the aquatic environment.

We will update the CoP for users and for suppliers to reflect current regulatory standards established by the SUD and better support those working with pesticides.

Equipment requirements

Testing arrangements of equipment have been in place for several years, as required by the 2012 Regulations. These ensure that application equipment in professional use is inspected regularly. The National Sprayer Testing Scheme (NSTS) is used to implement equipment inspection systems within the UK and is designated by the HSE on behalf of all 4 governments. The legislation sets out the regularity of inspection requirements. Professional users are required by legislation to conduct regular calibration and technical checks of PPP application equipment.

Pesticides application equipment in professional use and falling within the categories listed in regulation 11(1) of the 2012 Regulations, which includes spraying equipment mounted on trains or aircraft, boom sprayers longer than 3 meters and certain vehicle mounted or drawn sprayers, must be inspected within 5 years of the purchase date and every 3 years thereafter. Other pesticides application equipment for professional use (other than handheld equipment and knapsack sprayers) must be inspected every 6 years. A list of equipment testing requirements is available on the NSTS website.

Training

Distributors, advisors and professional users of pesticides have access to training by bodies approved by the regulator (list of UK designated bodies and recognised specified certificates), as required by the 2012 Regulations. It is also a statutory requirement for end users of pesticides authorised for professional use to hold an accredited certificate (unless they are working under the direct supervision of someone who holds one, for example, in a situation where they are being trained).

The private market provides systems of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for ongoing training, development and assurance. For example, agronomists must achieve CPD points to maintain their membership of the BASIS Professional Register and there is also an annual BASIS Store Inspection scheme which requires that the facilities and management arrangements of the stores are assessed annually by a suitable independent expert.

Under the 2012 Regulations, distributors (other than micro-distributors, with less than 10 employees for most of a financial year) who sell plant protection products to end users are required to have staff available at the time of sale who hold an advisor’s certificate. All distributors of non-professional products are required to provide general information regarding the risk for human health and the environment of plant protection product use.

Official controls and risk-based inspections

The Official Controls (Plant Protection Products) Regulations 2020 and The Official Controls (Plant Protection Products) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2020 enable regulatory authorities to enforce legal requirements that apply to the placing on the market and safe use of PPPs.

These regulations create an obligation on those working with pesticides professionally to register with the relevant Competent Authority (Secretary of State for England, the Scottish Ministers for Scotland, the Welsh Ministers for Wales and DAERA for Northern Ireland). In Great Britain, Defra manages these registrations on behalf of Scottish and Welsh Governments, and a comparable register has been developed by DAERA for operators in Northern Ireland. The register helps regulators to deliver a programme of risk-based inspection visits, which will help us to better understand compliance with the legislation. Pesticide users can indicate whether they are a member of an assurance scheme when they register.

Pesticide Enforcement Officers (PEO) at the HSE carry out these inspections across Great Britain and a similar programme will be undertaken by DAERA. Our aim is to target proactive support to where it is needed most, while recognising the good practice that is already happening. The inspections check that operators are using PPPs in accordance with the conditions specified on the label, keeping records of usage and meeting the requirements of the 2012 Regulations aimed at ensuring the safe use of PPPs. Read further information from the HSE about PEO visits. They also advise on how to comply with requirements of the pesticides legislation. Over the lifespan of this NAP, information gained through these visits will provide a picture of compliance. We will want to evaluate whether it meets our objectives to be proportionate, targeted, consistent, transparent and accountable.

We will use the evidence from inspection, enforcement and other official control activities, as well as wider intelligence gathering, to inform a targeted approach to intervention, including future inspection.

Case study: Official Controls Regulations — distributor visits

A visit to a country store distributing professional PPPs was conducted, during which several issues were identified. The company was storing their professional-use PPPs in a non-bunded area meaning that accidental release of pesticide could have harmed the surrounding environment. There were no trained staff to provide advice and guidance at the time of sale to customers on which PPPs they should use, the associated health and environmental risks from those products, and the safety instructions to manage those risks. In addition, professional use products were being used on the store property by a member of staff who was not appropriately trained.

Enforcement action was taken, and support and advice given to help the company attain compliance. In the immediate term, the professional-use products were moved to a temporary area capable of containing spillages, following which the company purchased a bunded chemical cabinet for product storage. The company also reached an agreement with their suppliers to provide the necessary advice to their customers at the time of sale. Finally, the company engaged competent contractors to carry out future spraying operations on their own site.

Online sales of PPPs

We also want to improve our understanding of where there are gaps in compliance in particular sectors and how they can be closed. Studies that we commissioned in 2022 and in 2023 to gather evidence of online sales of PPPs, showed that members of the public who are not qualified to use professional PPPs could make potentially unsafe purchase choices, without awareness that restrictions apply to a product and its usage. This use could risk causing harm to the environment or to public health.

We subsequently commissioned pesticide online sales banner testing research to design and test banners or warnings that could be incorporated into online sales listings to inform purchasers which products they are legally allowed to use. We will take forward the recommendations of this research with the aim of improving awareness online of the restrictions on sale of PPPs.

Actions to build and strengthen compliance

Action 15

Commission an evidence project to review where data from a range of indicators and metrics can further inform a risk-based approach to compliance.

Action 16

Review how membership of industry/assurance schemes might be taken into account as part of assessing users’ risk profiles, so inspections are better targeted.

Action 17

Ensure guidance on the use of PPPs, in particular, the ‘Codes of Practice for using plant protection products’ (and the ‘Code of Practice for suppliers of pesticides to agriculture, horticulture and forestry’), are updated to be current, remain clear and easily accessible, support compliance and embed IPM as a key part of our long-term approach to pest control.

Action 18

Engage with online marketplaces to discuss findings of research regarding online sales of professional PPPs, and approaches to increasing visibility of the legal requirements of their use for the general public.

References

Anastasiou E and others, ‘Precision Farming Technologies for Crop Protection: A Meta-analysis’ Smart Agricultural Technology 2023, volume 5, Article 100323 (viewed 18 September 2024)

Beaumelle L and others ‘Pesticide Effects on Soil Fauna Communities – A Meta-analysis’ Journal of Applied Ecology 2023, volume 60, issue 7, pages 1239-1253 (viewed 20 September 2024)

Cook S and others ‘Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for Biodiversity Enhancement. NECR575’ Natural England 2024 (viewed 20 September 2024)

Creissen HE and others, ‘Identifying the Drivers and Constraints to Adoption of IPM Among Arable Farmers in the UK and Ireland’ Pest Management Science 2021, volume 77 (issue 9), pages 4148-4158. (viewed 18 September 2024)

Garry F and others. ‘Future Climate Risk to UK Agriculture from Compound Events’ Climate Risk Management 2021, volume 32, Article 100282 (viewed 20 September 2024)

Garthwaite D and others, ‘Pesticide Usage Survey Report 302: Amenity Pesticide Usage in the United Kingdom’ Fera Science Ltd 2020 (viewed 18 September 2024)

Gunstone T and others ‘Pesticides and Soil Invertebrates: A Hazard Assessment’ Frontiers in Environmental Science 2021, volume 9, Article 643847 (viewed 20 September 2024)

Hallman C and others ‘More Than 75 Percent Decline Over 27 years in Total Flying Insect Biomass in Protected Areas’ PLoS ONE 2017, volume 12, issue 10, article e0185809 (viewed 20 September 2024)

He D and others ‘Problems, Challenges and Future of Plant Disease Management: from an Ecological Point of View’ Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2016, volume 15, issue 4, pages 705-715 (viewed 18 September 2024)

Pollard KM and others ‘Battling the Biotypes of Balsam: the Biological Control of Impatiens glandulifera Using the Rust Fungus Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae in GB’ Fungal Biology 2021, volume 125 (issue 8), pages 637-645 (viewed 20 September 2024)

Serrao J and others ‘Side-effects of Pesticides on Non-target Insects in Agriculture: a Mini-review’ The Science of Nature 2022, volume 109, Article 17 (viewed 20 September 2024)

Varah A and others ‘The Costs of Human-induced Evolution in an Agricultural System’ Nature Sustainability 2020, volume 3, pages 63-71 (viewed on 20 September 2024)

Annex 1: Statutory obligations for a Pesticides National Action Plan

Regulation 4 of the 2012 Regulations requires that the NAP:

- includes quantitative objectives, targets, measures and timetables to reduce risks and impacts of pesticide use on human health and the environment and to encourage integrated pest management (IPM) and use of alternative approaches or techniques to reduce dependency on the use of pesticides

- includes indicators to monitor the use of plant protection products containing active substances of particular concern (especially if alternatives are available) and targets for the reduction of their use

- describes how to ensure that the general principles of integrated pest management (set out in Annex 2) are implemented by all professional users by 1 January 2014

- lists plant protection product application equipment to which regulation 12(1) applies (in accordance with Article 8 (3)(a) of the SUD) (as described under Objective 3 ‘Equipment requirements’)

- describes how measures pursuant to Articles 5 to 15 will be implemented, which is set out below.

Summary of Articles 5 to 15 of the SUD and how they have been implemented

-

Requires that appropriate training (provided by designated bodies) is made available for professional users, distributors and advisors (Article 5 implemented by Regulation 5 of the 2012 Regulations)

-

Requires distributors to have sufficient staff available at the point of sale, and that the sale of pesticides authorised for professional use be restricted to persons who are certificated to use such pesticides (Article 6 implemented by Regulation 9 of the 2012 Regulations)

-

Requires distributors selling pesticides to non-professional users to provide general information regarding risks to human health and the environment (Article 6 implemented by Regulation 9 of the 2012 Regulations)

-

Requires that the general public is made aware of the risks and potential effects to human health, non-target organisms and the environment from the use of pesticides and the use of non-chemical alternatives (Article 7 implemented through the Prospective Investigation of Pesticide Applicators’ Health and the UK National Poisons Information Service)

-

Requires bodies responsible for implementing inspection systems to be designated and for certain pesticide application equipment in professional use to be subject to inspections at regular intervals (Article 8 implemented by Regulation 6 of the 2012 Regulations)

-

Requires that aerial spraying is prohibited. Allows derogation from prohibition of aerial use in certain special cases (via request for an aerial spraying permit which has specific conditions) (Article 9 implemented by Regulation 15 and 16 of the 2012 Regulations)

-

Requires that appropriate measures to protect the aquatic environment and drinking water supplies from the impact of pesticides are adopted (Article 11 implemented by Regulation 10 of the 2012 Regulations)

-

Requires the reduction of pesticide use or risks in specific areas (Article 12 implemented by Regulation 10 of the 2012 Regulations)

-

Requires that necessary measures are adopted to ensure that storage, handling, dilution, mixing cleaning and disposal operations do not endanger human health or the environment; that necessary measures are taken regarding pesticides used by non-professional users to avoid dangerous handling operations; and that storage areas for pesticides for professional use are constructed in such a way as to prevent unwanted releases (Article 13 implemented by Regulation 17 of the 2012 Regulations)

-

Requires that all necessary measures are taken to promote low pesticide-input pest management, giving priority to non-chemical methods wherever possible, so that professional users of pesticides switch to practices and products with the lowest risk to human health and the environment among those available for the same pest problem (Article 14 implemented by Regulation 4 of the 2012 Regulations, the 2013 and this National Action Plan)

-

Requires calculation of risk indicators, identification of trends and identification of priority areas and good practices that can be used to support achievement of the objectives of the SUD (Article 15, implemented through the 2013 and this National Action Plan)

Annex 2: Integrated pest management principles

Integrated pest management (IPM) is a holistic approach which:

- carefully considers all available plant protection methods and uses appropriate measures to (a) discourage the development of populations of harmful organisms (which includes invertebrates, diseases and weeds), or (b) control an established population

- keeps the use of plant protection products and other forms of intervention to levels that are ecologically and economically justified

- minimises risks to human health and the environment

IPM develops and maintains resilient ecosystems to pests and diseases, while supporting natural pest control mechanisms.

Although many IPM measures were initially developed for agricultural and horticultural applications, it is a sustainable approach that can be applied to the amenity and amateur sectors, as well as forestry.

What does IPM mean in practice?

IPM involves following some key general principles. These are referenced in the 2012 Regulations, which came into force on 18 July 2012 and transpose the SUD, 2009/128/EC, in relation to the use of pesticides that are plant protection products (PPPs).

Prevention

The use of preventative and cultural methods reduces the risk of pests becoming established. These can include crop rotation, cultivation and tillage practices (how the land is prepared to grow crops), growing pest-resistant varieties, hygiene measures (for example, regular cleansing of machinery and equipment), sweeping hard surfaces and encouraging natural predators.

Monitoring

Not all potentially damaging insects and weeds require control. Animals and plants classified as pests or weeds may be important to the structure and function of local ecosystems.

Effective monitoring includes inspection, pest identification, forecasting and assessing levels of pest populations. It ensures that pesticides are only used when necessary and that the correct control is selected and is applied in the right way at the right time.

Monitoring should include observations in person and where feasible, scientifically sound forecasting and early diagnosis systems, as well as the use of advice from professionally qualified individuals, advisers or agronomists.

Thresholds

Robust and scientifically sound thresholds (considering pest pressure, region, crops and particular climatic conditions) are essential components for decision making and rely on effective monitoring.

Once a threshold, or predicted threshold, has been exceeded, such as when pest population levels, pest damage or weed prevalence become economically or environmentally unsustainable, actions should be taken to control the pest. The emphasis is on control rather than eradication, as allowing a pest population or weeds to survive at reasonable levels may not only benefit natural predators and pollinators but also help prevent resistance developing by reducing pest exposure to pesticides.

Intervention and control

The methods of pest control should be selected based on both effectiveness and risk. Sustainable physical, biological and other non-chemical methods must be preferred to chemical methods if they are practical and provide satisfactory pest control.

Physical – including hand weeding, mechanical weeding, physical barriers such as netting over small fruits and vacuuming to remove insects.

Biological – including the use of predatory species, insect mating disruption techniques and biopesticides. It is important to recognise that there are different categories of biopesticides, and they do not inherently pose less risk to the environment. They should also be used in a targeted and responsible way.

When chemical pesticides are used, they should be applied at levels which are necessary. For example, minimum effective dose and application frequency as well as targeted application to minimise potential negative impacts. Use of precision technology, spot treatments, weed wipers, drift reduction, and other similar tools and techniques will help with optimising the application.

Managing resistance

Anti-resistance strategies should be utilised. Where the risk of resistance against a plant protection measure is known and where the level of harmful organisms requires repeated application of pesticides to the crops, available anti-resistance strategies should be applied to maintain the effectiveness of the products.

Review and evaluation

The success of all plant protection and pest control measures should be reviewed regularly so that effectiveness can be assessed, adjusted and tailored to each situation. This may be done through effective IPM plans which are reviewed year on year.

Annex 3: Pesticide facts and figures

The following data has been sourced from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nation (FAO) and was correct as of August 2024.

Agricultural pesticide use across the world has been gradually increasing since 1990. The FAO estimates that 3,441 metric kilotons (kT) of pesticides were used globally in 2020. This demonstrates a 91% increase from 1990 when an estimated 1,806 kT were used (these values are subject to retrospective updates by FAO if new data is received).

Over the same period in the UK, the total weight of active substance applied by farmers and growers has decreased by nearly 60% since 1990 (including sulphuric acid) or by one third (excluding sulphuric acid) (PUS).There were 19.96 kT applied to arable crops in 1990 (excluding sulphuric acid), compared with 12.55 kT in 2020 (Pesticide Usage Survey, 2020). Sulphuric acid was used as a desiccant (drying agent) on potatoes and was phased out between 2004 and 2010. It was applied at rates several orders of magnitude greater than other pesticides but over small spatial areas (around 0.2% of total cropped area). It consequently made up a disproportionate share of weight applied.

There are a range of factors which are likely to impact which pesticides are being used in the future – affecting both weight applied and load. Some of the major factors — biodiversity loss, pesticide resistance, climate change, and availability of products are discussed below.

Biodiversity and insect abundance are crucial for our economic prosperity. Pollinators provide benefits of around £630 million per year to UK crop production. The factors contributing to biodiversity loss are complex and varied, especially as other drivers of biodiversity loss like land use change and habitat loss are also often associated with intensive agricultural practices. However, there is growing evidence that pesticides can impact non-target species such as pollinators and soil-dwelling invertebrates (Beaumelle and others, 2023). A review of 400 studies found that pesticides had a negative effect on 70.5% of biodiversity measures for soil invertebrates (Gunstone and others, 2021) demonstrating that they are a contributing factor to the biodiversity decline we are seeing. As another example, a recent review highlighted the harmful effects of pesticides on beneficial insects such as pollinators and parasitoids (Serrao and others, 2022).

Biodiversity has been in decline for decades (Hallman and others, 2017) and halting the decline of species in the timeframe of the 2030 species abundance target in England (and 2030 target under development in Wales) will be a substantial challenge and require action across the full range of environmental pressures. IPM can have significant benefits in reducing pressures and improving the environment. Studies have shown that IPM can help to improve natural capital, including soil health and water quality, and can lead to increased abundance and diversity of beneficial insects (Cook and others, 2024).

Over-reliance on individual products is a driver of pesticide resistance, which leads to issues whereby pesticides no longer provide effective control. In England, black-grass resistance to herbicides is extremely widespread and is estimated to cost farmers nearly £400 million per year in lost gross profits (2014 prices) (Varah and others, 2020).

It is also likely there will be additional pest control challenges resulting from climate change in future years because of more unpredictable weather and changes to the range and frequency of some pests and diseases (find information on the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations website). In the longer term (30 to 50 years’ time), it is predicted that late blight — a disease affecting potato crops which occurs in warm, humid weather — is likely to occur more often across the UK, with the greatest increases in western and northern regions. In east Scotland, a region which currently has a high concentration of potato farming, potato blight may occur around 70% more often (Garry and others, 2021).

The makeup of available products will change over time. A number of approved active substances may be withdrawn in future years. This could be because they have not passed the risk assessment with updated scientific knowledge, or because authorisation holders have decided not to apply for review for commercial reasons. There are now around 14% fewer active substances available in Great Britain than there were in 2016.

The choices users make about certain pesticides will also change with the adoption of alternative techniques and innovations in technology.