UKHSA Advisory Board: preparedness for chemical, radiological and nuclear threats

Updated 10 May 2023

Date: Tuesday 14 March 2023

Sponsor: Isabel Oliver

Purpose of the paper

The purpose of this paper is to describe the current chemical, radiological and nuclear threats to health and highlight the specialist scientific emergency response functions, capabilities and responsibilities of the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) to prepare and respond to these threats.

UKHSA also has important responsibilities in relation to other environmental risks including extreme weather events and natural hazards but those will be covered in a separate future paper.

Recommendations

The Advisory Board is asked to:

- note the activities underway in UKHSA to build capacity and capability to protect health from chemical, radiological and nuclear threats

- comment on the current work and development work underway in UKHSA and identify any significant gaps in the approach

- comment on the important choices that UKHSA and government may need to make to improve preparedness

Summary

Chemical and radiation hazards are a major cause of ill health and mortality.

The risks to health from these hazards, both accidental and deliberate are increasing; the burden of ill health is greatest among the most disadvantaged groups in society.

The UK National Security Risk Assessment (NSRA) and the National Risk Register (NRR) identify specific risk scenarios that include chemicals and radiation. As a Category 1 responder under the Civil Contingencies Act, we must plan for and be able to respond to these risks.

Several agencies and government departments have responsibilities in this area. UKHSA’s unique role is the health risk assessment and protection of the public’s health.

UKHSA has identified the need to strengthen capabilities to respond to chemical, radiological and nuclear incidents as one of its strategic priorities. Additional funding was allocated to this priority in August 2022 following the 2022 to 2023 financial settlement.

An action plan is being implemented that will ensure we have increased numbers of trained specialist staff, a cadre of staff able to provide surge support from across the organisation and a better understanding of the surge capacity elsewhere in government, academia and industry. Once the enhanced capacity and capability are in place, this will allow UKHSA to better respond to such incidents.

Background

The aim of this paper is to give an overview of the work that UKHSA is doing to protect the health of the UK population from chemical, radiological and nuclear threats and to discuss the planning and preparedness work being done within the organisation to strengthen our capacity and capability to respond to these threats. This paper complements the one the Board considered on infectious diseases threats in January 2023.

Chemicals and radiation, whether of natural origin or produced by human activities, are part of our daily life and environment. As well as the risk of release of harmful chemicals, nuclear material and radiation into the environment as part of acute incidents such as fires and explosions, we are all exposed, every day to varying levels of hundreds of different substances present in air, food and water.

UKHSA is the expert body legally responsible for ensuring health security in relation to chemical, radiological and nuclear threats and is a Category 1 responder under the UK Civil Contingencies Act (2004). The response to chemical, radiological and nuclear incidents is always a multi-agency response; however, for the majority of emergency incidents the lead rests with other bodies for example the police, local authorities or other government departments.

UKHSA’s unique role is the health risk assessment and protection of the public’s health.

All parts of UKHSA contribute to our work to secure health from these threats. The health protection teams (HPTs) lead the local response, and the Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards (RCE) Directorate provides specialist advice, science and technical services to protect the public from exposure to chemicals and poisons, ionising and non-ionising radiation, and other environmental hazards. RCE also has staff co-located with HPTs to support local areas, as well as in Wales to help support Public Health Wales with chemical and environmental hazard response.

UKHSA uses event-based surveillance (EBS) for situational awareness of chemical incidents occurring globally including those that have the potential to cross international borders, which require a joined-up approach from multiple sectors and countries. UKHSA works closely with and for partners across Europe and globally, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and international organisations such as the International Atomic Energy Agency, for provision of mutual support in terms of horizon scanning, planning and emergency preparedness.

Risk assessment

Chemical, radiological and nuclear threats to health are included in the NSRA and the public-facing NRR with several risks identified:

- deliberate attacks involving chemicals

- deliberate attacks involving radiation

- accidents at major hazard (control of major accident hazards, or COMAH) sites or on fuel infrastructure

- civil nuclear accidents or exposures from stolen or lost goods

- natural and environmental hazards (for example, extremes of temperature, flooding, wildfires, volcanic eruptions, space weather, poor air quality)

The ever-increasing number and variety of substances manufactured, transported and used globally is increasing the risk of human exposures and subsequent adverse health effects from these substances.

CBRN is the acronym used to describe the malicious use of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear agents (CBRN) with the intention to cause significant harm or disruption. CBRN incidents are rare (see Appendix 1 for additional information), but the risk is considered to be changing globally due to advances in technology and increased likelihood of terrorists using unconventional weapons. These risks are assessed in the NSRA. Armed conflicts around the world can pose risk to nuclear installations.

The development of the national threat assessments has involved UKHSA expert input to a Cabinet Office standardised framework throughout 2021 to 2022. In addition, UKHSA All Hazards Intelligence division (AHI) is developing a health security threat assessment which will compare a range of current public health threats that the UK faces and examine how these may evolve over the next 5 to 10 years. UKHSA is also currently reviewing its response capabilities against these risks.

The main hazards of concern are considered under the separate sections below on chemicals, and radiological and nuclear threats.

Impact on chemical and radiation risks

Societal and other factors that impact chemical and radiation risks

Exposure to chemical and radiation hazards is a major cause of ill health and deaths. The deliberate release of toxic and harmful substances is linked to terrorism, political instability, and conflict. The burden of disease linked to exposure to environmental hazards is not equally distributed, with the most disadvantaged having greater risk of exposure and the consequent impacts on health.

While the burden of disease from environmental hazards is not well understood, it is almost certainly underestimated. The skills and expertise in some of the main scientific disciplines, such as toxicology, that are required to understand and mitigate risks to health are very limited, not only in the UK but internationally.

Pollution is the largest environmental cause of disease and premature death in the world today, killing, disproportionately, the poor and the vulnerable. In countries at every income level, disease caused by pollution is most prevalent among the most disadvantaged groups in society. Children are also especially vulnerable and even extremely low dose exposures to pollutants during the early stages of life can result in disease or disability. Behavioural factors also play a role. For example, behaviours and attitudes to sunlight and sun bed exposure, both sources of ultraviolet (UV) light, impact on skin cancer risk.

UK regulation that relates to radiation and chemical exposure health risks has, for many years, been based on European Union (EU) legislation. This is changing following EU exit, impacting UKHSA’s workload as we will need to provide substantial input into developing future regulatory frameworks. UK REACH (registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals) was brought into UK law in January 2021, which regulates chemicals placed on the market in Great Britain. Legislation aims to mirror EU REACH by providing high level of protection to public health and the environment from the use of chemicals.

Chemical hazards

Chemicals have contributed significantly to global improvements in human health, food security, productivity and quality of life. The production and consumption of chemicals is rising. Global chemical sales were valued at €3.4 trillion in 2017 with China, the EU and US the largest producers. The industry contributes £18 billion to the UK economy each year.

The European Commission estimates there are over 100,000 chemicals on the EU market, only a small proportion of which have been evaluated for their impact on human health and the environment. Most chemicals in use today have not been tested for their safety or toxicity and there is growing awareness about chemicals of emerging concern, substances where toxicity had not been previously recognised such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). There are strong health inequalities associated with exposure to chemical hazards.

Exposure to harmful chemicals is thought to be increasing with new or emerging risks being identified regularly. Over 60% by tonnage of the chemicals on the EU market are hazardous to human health or the environment. We are exposed to chemical substances through inhalation, ingestion or contact with the skin or eyes. Exposure to hazardous chemicals can be acute or chronic and can have immediate as well as long-term health effects.

Some chemicals are carcinogens, endocrine disruptors or allergens or can cause neurological disorders and other acute of chronic health effects. Chemicals can affect intellectual development, immunity and reproduction and some are known to have transgenerational effects. The health effects are determined by:

- the type of chemical

- the quantity

- duration

- mechanism of exposure

- individual susceptibility factors

WHO estimates that just over one third of coronary heart disease, the leading cause of deaths and disability worldwide, and about 42% of stroke, the second largest contributor to global mortality, could be prevented by reducing or removing exposure to chemicals such as from ambient air pollution, household air pollution, second-hand smoke and lead.

UKHSA responds to approximately 1,000 incidents per year, the majority of which are relatively short-lived fires releasing toxic smoke, or accidental releases or incidents involving known chemicals and for which health advice and response plans are in place and well exercised. UKHSA responds to major or large-scale fires at industrial, commercial, or agricultural sites, where toxic smoke or secondary hazards such as asbestos will potentially adversely affect local communities.

A chemical incident is defined as “an unexpected, uncontrolled release of a chemical from its containment”. Chemical incidents may be caused by accidental (for example, chemical spillages, fires) or deliberate (for example, terrorist) factors.

Globally, there are multiple chemical incidents involving the exposure, or potential exposure of tens of thousands of people every year. Recent accidents include the 2013 Lac-Mégantic rail disaster and the 2015 Tianjin explosions. This has been accompanied by an alarming rise in the criminal dumping of chemical waste and deliberate use of chemical agents including:

- acid attacks

- Sarin in Syria

- VX in Malaysia

- Novichok in the UK and Russia

These all highlight the ever-present threat from chemical incidents.

There are numerous other longer-term chemical hazards of concern. We have programmes of work to reduce health harm from lead, carbon monoxide, chemical contaminants of drinking water, such as:

- PFAS

- poor indoor air quality from volatile organic chemicals or mould

- bioaerosols

- microplastics

- nanoparticles

Much of this work is funded through health protection research units (HPRUs), and other collaborations with academia and industry.

Legislation and regulation of chemical hazards

There is multiple and complex legislation in relation to chemicals and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has the policy lead for regulations controlling the use of chemicals in the UK. UKHSA provides expert toxicological and public health risk assessment advice to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), Environment Agency (EA) and Defra for chemical regulation. This is tailored to provision of scientific advice, and support for strategic priority setting for regulation of substances where there is exposure to the general public and where public communication and engagement are required.

UKHSA contributes to the Defra Chemicals Delivery Board, which provides the strategic direction and takes non-ministerial positions on chemical regulation issues. UKHSA and Defra work together on the development of internationally agreed protocols for chemical safety testing assessments at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Input into OECD processes is especially important following EU exit.

Although Defra, HSE and EA have the lead for chemical regulation in the UK, they do not cover public health risk assessment. UKHSA plays a crucial role within the UK’s chemical regulation system to make sure that health is protected by ensuring that chemicals of concern for public health are sufficiently prioritised for regulatory action, while striking a balance in supporting economic growth.

Chemical hazards: UKHSA’s roles and responsibilities

Prepare

Surveillance of environmental exposures is vital to understanding the impact of chemical exposures on health. UKHSA’s environmental surveillance is less developed and resourced than our infectious diseases surveillance.

Our environmental public health surveillance system (EPHSS) is designed for the public health community to interrogate data and information on environmental hazards, exposures, and related health outcomes from various sources, most significantly the UKHSA’s chemical and environmental hazards incident database. This information is used to prepare and prevent harm.

UKHSA provides expert public health advice to government departments and agencies as a statutory consultee to inform their regulatory activities and to minimise risks to health.

Through our environmental public health programme, UKHSA works with important stakeholders including the devolved administrations to coordinate preparedness and prevention programmes.

UKHSA contributes to the development of multiagency incident response plans and participates in regular multi-agency exercises to test our response.

Respond

UKHSA has a unique role as part of the multi-agency response to accidental or deliberate chemical releases. UKHSA provides the public health risk assessment and advice on appropriate protective actions to be implemented, including medical countermeasures.

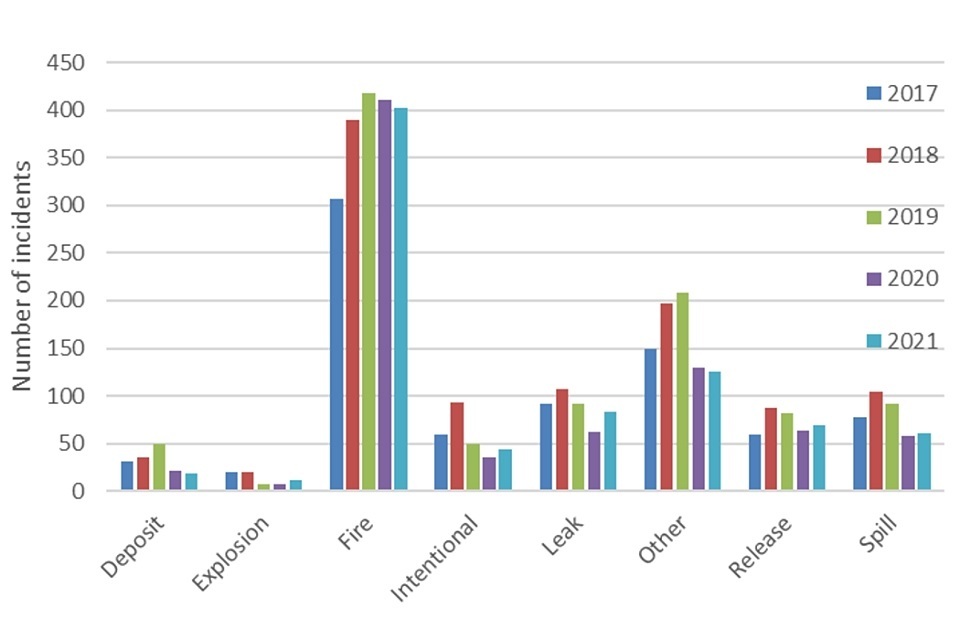

Appendix 2 gives a summary of RCE chemical incident response. Regional distribution of incidents between 2014 and 2021 are shown in Table 1, and Table 2 indicates the total number of waste fires managed during this time. Figure 1 is a bar chart showing trends by incident type between 2017 and 2021.

Although total figures for incidents were slightly reduced during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the total number of waste fires remained stable. During the pandemic, public health advice to ensure health protection had to be altered to accommodate COVID-19 protection advice.

Table 1. Annual regional distribution of incidents for the period 2014 to 2021

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North East | 23 | 21 | 17 | 17 | 22 | 29 | 29 | 32 |

| North West | 61 | 69 | 61 | 72 | 87 | 72 | 54 | 49 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 100 | 67 | 101 | 85 | 96 | 78 | 51 | 76 |

| East Midlands | 68 | 72 | 42 | 79 | 93 | 77 | 53 | 58 |

| West Midlands | 78 | 102 | 99 | 112 | 114 | 143 | 113 | 156 |

| East of England | 35 | 54 | 65 | 74 | 100 | 75 | 86 | 51 |

| London | 120 | 116 | 95 | 125 | 211 | 235 | 193 | 155 |

| South East | 191 | 133 | 139 | 110 | 121 | 131 | 83 | 109 |

| South West | 116 | 109 | 87 | 122 | 189 | 158 | 122 | 128 |

| Total | 792 | 743 | 706 | 796 | 1,033 | 998 | 784 | 814 |

Table 2. Waste fires sites for the period 2014 to 2021

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of incidents | 43 | 30 | 27 | 34 | 28 | 39 | 29 | 24 |

Figure 1. Trends for the incident type for the period 2017 to 2021

UKHSA has strong links with the emergency services. Unlike notifiable infectious diseases, there is no requirement to inform UKHSA of chemical exposures. In this context, we have developed arrangements with fire and rescue and ambulance services to facilitate rapid and effective public health action. Our real-time syndromic surveillance system collects information from ambulance services, emergency departments and GPs and provides warnings of unusual patterns of illness that may be related to a release of toxic or hazardous substances.

UKHSA commissions the UK National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) that provides expert advice on all aspects of acute and chronic poisoning. NPIS provides active surveillance and toxicovigilance for chemical and radiological exposures and ensures that UKHSA are aware of any actual or potential incidents. NPIS is the frontline NHS for advice on the diagnosis, treatment and care of patients who may have been poisoned accidentally or intentionally.

UKHSA maintains emergency response arrangements and facilities in readiness for a wide range of chemical and environmental emergencies which may impact upon public health. These arrangements are designed to dovetail with the wider UKHSA Incident Response Plan. The UKHSA response to a chemical incident is delivered collaboratively drawing on skills and resources from groups across the organisation. Unlike with infectious diseases, there is not normally a lead time to build response capacity.

The emergency services respond frequently to chemical incidents. The majority are accidental exposures, but some involve the use of chemicals for criminal purposes, for example acid attacks, production of illegal drugs or the making of explosives. Deliberate releases are rare, and in the early stages of an incident the intent may not be known, however the principles of the health protection response are the same.

UKHSA’s contribution to the multi-agency response is primarily through the Emergency Coordination of Scientific Advice (ECOSA) and the local Scientific and Technical Advisory Cell (STAC) of the Strategic Coordination Group or through the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), at the national level.

UKHSA leads or supports the following:

- hazard identification and characterisation

- exposure assessment

- public health risk assessment and health protection advice to the public including protective actions such as sheltering, or decontamination

- clinical management advice (NPIS) and deployment of medical countermeasures (UKHSA)

- laboratory assessments and human and environmental biomonitoring (UKHSA under development)

- advice on remediation methods and advice on reasonable residual hazard levels

- monitoring of the public’s health

UKHSA is a partner with the Environment Agency in the National Air Quality Cell arrangements for air quality monitoring in major incidents. During 2022, the Air Quality Cell was set up 14 times during 2022 with monitoring to aid public health risk assessment carried out for 3 incidents.

Build

UKHSA works in partnership with academia to better understand environmental health threats and develop the evidence for health security. We build capacity through our National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) HPRUs that also support incident response and recovery.

UKHSA plays an important role internationally. We host the WHO Collaborating Centre for the Management of Chemical Exposures that provides specialist advice during chemical incidents and supports global training. We represent the UK at OECD, which is vital for the development of chemicals regulation in the UK following departure from the EU and participate in international programmes. We also contribute to global health security through capacity building programmes to help strengthen compliance with the International Health Regulations (IHR).

We contribute to global health security by supporting countries with capacity building activities. We have developed and successfully delivered in-country and online training, guidance and tools to 20 partner countries. We support WHO and foreign national agencies to strengthen poison centres and toxicological capacity internationally.

UKHSA provides the secretariat for 4 independent expert government committees:

- the Committee on Carcinogenicity of chemicals in food, the environment and consumer products (COC)

- the Committee on Toxicity (COT)

- the Committee on Mutagenicity (COM)

- the Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollution (COMEAP)

This work, as well as our research, academic collaborations and PhD studentships, strengthens our expert workforce and capacity.

Health protection from chemical threats

UKHSA’s unique skills and expertise are recognised internationally. Our strengths include:

- our multidisciplinary workforce

- our national to local infrastructure

- our academic partnerships

- our toxicological expertise, including partnerships with NPIS clinical toxicologists

Priorities to strengthen preparedness from chemical threats

Chemical hazards cause morbidity and mortality. The risks of natural, accidental and deliberate exposure are all increasing. It is likely that a terrorist group will launch a successful CBRN attack by 2030. A plan to strengthen our capabilities has been agreed with additional investment secured in 2022 to 2023 for this purpose.

Important components of the plan include:

- increasing the capabilities and capacities of specialist staff across and our current laboratory capacity

- identifying and training a cadre of staff across UKHSA able to provide surge support for chemical incidents

- working with system partners, including national (for example, Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL), Food Environment Research Agency (FERA), Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and NHS) and international partners, to determine their ability to provide specialist surge support to UKHSA in the event of an incident; exploring with partners what surge capacity, including from academia and industry, is available

Radiation

Some exposure to radiation is unavoidable as it exists naturally in our environment including air, soil and water, for example, UV light from sunlight or radon from soil and rocks. There are many applications of ionising radiation in industry and medicine, all of which are well regulated.

Longer term health effects from exposure to radiation

Ionising radiation damages our DNA and is a known carcinogen and the health effects are dose dependent. In the UK, it is estimated that approximately 1,000 lung cancers per year are due to radon exposure.

UV light is carcinogenic to the skin, with around 16,000 melanoma cases per year in the UK and around 200,000 non-melanoma skin cancers. In addition to the increased risk of cancer, there are increasing concerns that low level exposures may lead to cardiovascular diseases and cognitive dysfunction.

The long-term health effects of exposure to non-ionising radiation, such as radiofrequency electric and magnetic fields (EMF), are of significant public concern. These are associated with the rise in the use of mobile telecommunications and its evolutions through the successive generations, known as 4G or 5G. UKHSA works to understand, assess and communicate these risks. Extensive research to date has not identified any ill health effects at the levels of exposure experienced by the general population.

Acute health effects

Exposure to high levels of radiation can occur following an accident or a malicious release as a result, for example of a terrorist attack. Acute exposures to high levels of radiation can cause immediate or severe health effects, damage to tissues and even death (see Appendix 3 for more information on ionising radiation effects on health and health burdens under routine and incident scenarios).

UKHSA protects health from the adverse health effects associated with radiation exposure and provides health security in both acute and chronic exposures. We deliver a range of radiation protection functions that can flex between routine protection activities and be drawn upon in case of a radiation emergency or incident. These cover all forms of ionising and non-ionising radiation. Under routine conditions, the functions facilitate the safe use of radiation in industry and medicine and protect the wider public.

Protection from radiation under both routine and emergency conditions requires the ability to detect and quantify sources and exposures and assessment of health impacts. UKHSA maintains these capabilities to respond to radiological or nuclear incidents.

Reasonable worst-case scenarios for planning

There is a wide range of potential incidents across a wide range of environments and sites involving sources of radiation or nuclear materials that would require an enhanced public health response, thus there is no one typical radiological or nuclear incident scenario.

The range encompasses operating and decommissioned nuclear facilities, nuclear powered vessels and satellites, accidental or deliberate release events and space weather.

Past experiences also highlight the range of scenarios that may present themselves in the future, including the:

- 1986 Chornobyl accident that led to some 30 direct deaths and injuries plus increased thyroid cancer incidence

- 2006 poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko, causing one death and leading to 129 contaminated persons and multiple locations across London with contamination with polonium-210

- 2011 Fukushima incident where no direct casualties were reported, and elevated cancer risks will be challenging to detect

UKHSA continues to contribute to revisions to the NSRA in relation to radiological and nuclear threats. These provide the basis for reasonable worst case scenario planning.

Radiation and nuclear incidents: UKHSA roles and responsibilities

UKHSA has a legal responsibility to deliver a health protection response to radiation and nuclear incidents. UKHSA provides specialist technical components of the response to radiation incidents across the whole UK and in support of UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

Prepare

UKHSA maintains the capabilities needed to respond to large scale and high impact incidents. We currently respond to 5 to 10 incidents per year, which are generally small scale. Additionally, we contribute to regulatory emergency exercises required at all UK nuclear sites with off-site plans, local and national counter terrorism exercises, and international cooperation exercises. These currently number 15 to 20 per year.

International events involving radioactive material are of high interest to UK government. UKHSA works closely with partners internationally to prepare for and respond to these.

Respond

As noted previously, UKHSA takes a lead on public health matters in radiation incidents as part of a well-developed multi-agency response. Input is primarily through the STAC at the local level and SAGE at the national level and is underpinned by specific activities as documented in the UKHSA radiation emergency plan.

The main specialist roles and responsibilities include:

- environmental monitoring and coordination or deployment of monitoring resources

- assessments of the public health impacts of radiological releases to inform the need for protective actions

- internal dose assessments

- biological dosimetry

- continued advice during the transition to recovery and in the recovery period

These functions, including the provision of advice through STAC or SAGE, require support functions which are included within the UKHSA radiation emergency plan. Within UKHSA, specialist radiation staff work in close cooperation with local HPTs and the senior medical advisors in Public Health Clinical Response. The Behavioural Science and Insights Unit and Communications teams support the development and delivery of advice to the public.

UKHSA provides both technical and secretariat support to the Joint Agency Modelling (JAM) process. This is a multi-agency arrangement to provide co-ordinated information on the impacts of radiation emergencies to SAGE.

On behalf of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), UKHSA coordinates the National Arrangements for Incidents involving Radioactivity (NAIR). This is a set of national arrangements to assist the emergency services in situations where radioactive material is suspected, the public may be at risk and, crucially, for which there are no formal or adequate alternative arrangements. NAIR typically assists with small scale incidents of which there are approximately 5 per year.

Deployed NAIR response comes from NHS medical physics departments and the nuclear industry at the request of the police or other emergency services. Most ‘NAIR incidents’ are small scale. UKHSA is directly involved in the response to any complex incident of where there is an actual or potential risk to public health.

Build

We maintain our expertise and our capabilities ready to respond through research and commercial activities. We work to strengthen the evidence-base for health security building capacity to support our health protection functions including through 4 NIHR HPRUs:

- chemical and radiation threats and hazards (Imperial College London)

- environmental change and health (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine)

- environmental exposures and health (Imperial College London)

- environmental exposures and health – developmental (University of Leicester)

UKHSA’s radiation protection services support the safe use of radiation in industry, medicine and the academic sector. We issue and process 500,000 personal radiation dosemeters per year, we have over 2,000 clients for our Radiation Protection Advisor service, we carried out nearly 4,500 dental x-ray set assessments, we analysed and shared around 11,000 voluntary radiotherapy error reports to reduce such errors in the future.

We work internationally to prepare and to protect health. We work with all the main international bodies responsible for developing radiation protection standards internationally (United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, International Commission on Radiological Protection, International Atomic Energy Agency and WHO) and with institutes and universities in many countries.

Our specialist radiation protection workforce and the work conducted are recognised internationally and develop the specialist workforce of the future, for example through our 22 PhD students fully or partly-funded through the HPRUs and 9 PhD students funded through UKHSA’s internal PhD funding scheme.

Radiation threats to health: prevention and preparation

UKHSA’s strengths to prevent and prepare for radiation threats to health

UKHSA has a full range of capabilities that ensure that the public are protected from the risks of exposure to all forms of radiation while benefiting from its uses. Under routine conditions, UKHSA’s specialist radiation protection workforce is deployed flexibly to maintain high standards of radiation protection across the UK, maintaining the skills required in case of an emergency incident.

We have notable strengths in radiation monitoring and both internal and external dose assessment. The regular programme of civil and military radiation emergency exercises keeps the workforce prepared for actual incident response.

We maintain assets such as our national registry for radiation workers that are major contributors to global efforts to improve the assessment of health risks to low dose and chronic radiation exposures. This long-standing epidemiological study follows the health of the UK radiation or nuclear workforce and provides direct evidence of risk to UK citizens (1) in relatively low dose and chronic exposure situations. Our epidemiological studies are complemented by a programme of experimental studies to improve the assessment of radiation risks (2) where direct human data is not available.

We deploy our capabilities to meet our wider health security needs. For example, our radiological expertise has been instrumental in scoping and implementing studies assessing whether UV air disinfection devices can reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and other airborne pathogens in high-risk settings.

Priorities to strengthen preparedness for radiation incidents

The situation in relation to radiation protection is similar to chemical hazards with increasing risks. Additional investment was secured in 2022 to 2023 to strengthen our capabilities to respond to radiation and nuclear incidents. The programme of work includes:

- strengthening the specialist workforce, notably for Radiation Protection Advisors

- the development and delivery of basic training materials to widen the understanding of our radiation protection responsibilities across the Agency

- the development of novel innovative high throughput methods for biological dosimetry of radiation exposure in individuals

- bolstering our capacity to undertake environmental monitoring through the purchase of new equipment

- building our emergency radiochemistry capacity

- improving our radiological incident consequence predicative computer models and the skilled workforce to maintain these

- developing a programme of internal training and exercising to ensure newly recruited staff have the skills and experience required for emergency response activities

Important system factors to prepare and coordinating cross-government departments

UKHSA would like to engage more with DHSC, including with ministers, to highlight its chemical, radiological and nuclear responsibilities and capabilities.

UKHSA works closely with various government departments as important NSRA risk owners for chemical, radiological and nuclear incidents, such as:

- Home Office

- Defra

- the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT)

- Cabinet Office

UKHSA needs to work closely with these departments and DHSC to ensure system-wide preparedness and to protect health.

Toxicology laboratory capacity

UKHSA is building its capability and intends to collaborate with other public sector research establishments (PSREs) to strengthen system-wide capacity and capability.

Coordination, contingency and communication

Preparedness and response to chemical and radiation incidents requires close working across government departments. Clarity on governance arrangements, roles and responsibilities communications is vital.

The regular exercising of emergency plans related to major nuclear sites in the UK is required by the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and involves multiple players, including UKHSA; DSIT, ONR, the police, ambulance and fire services among others. UKHSA works with local partners in the planning and delivery of such exercises.

Regulations

The UK has repatriated a range of regulatory functions that rest primarily with Defra. The additional workload means that UKHSA is currently challenged to provide all the resource necessary in support of Defra and other government departments to support chemical regulation nationally and internationally.

Conclusions

Chemical and radiation hazards are a leading cause of ill health and mortality.

The risks to health from these hazards, both accidental and deliberate are increasing; the burden of ill health is greatest among the most disadvantaged groups in society.

The UK NSRA and NRR identifies specific risk scenarios that include chemicals and radiation. As a Category 1 responder under the Civil Contingencies Act, we must plan for and be able to respond to these risks.

Several agencies and government departments have responsibilities in this area. UKHSA’s unique role is the health risk assessment and protection of the public’s health.

UKHSA has identified the need to strengthen capabilities to respond to chemical, radiological and nuclear incidents as one of its strategic priorities. Additional funding was allocated to this priority in July 2022 following the 2022 to 2023 financial settlement. A workforce development plan has been put in place and urgent recruitment of a range of specialist staff is underway.

Our plan includes work to strengthen wider health security capacity and identify and train a cadre of staff able to provide surge support for chemical, radiological and nuclear incidents.

Work is in progress with UK system partners including:

- DSTL

- FERA

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ)

- DSIT

- NHS

- international partners to determine their ability to provide specialist surge support to UKHSA

This work is being extended to industry and academia.

Once the enhanced capacity and capabilities are in place as a result of this new investment, UKHSA will be better able to respond effectively to chemical, radiological and nuclear threats.

Professor Isabel Oliver

Chief Scientific Officer

March 2023

References

1. Examples: Hunter and others, Extended analysis of solid cancer incidence among the Nuclear Industry Workers in the UK: 1955-2011. Radiat Res. 2022 Jul 1;198(1):1-17; Hinksman and others, Cerebrovascular Disease Mortality after occupational Radiation Exposure among the UK National Registry for Radiation Workers Cohort. Radiat Res. 2022 May 1;197(5):459-470).

2. Examples: Abdelhalim and others, Higher Incidence of Chromosomal Aberrations in Operators Performing a Large Volume of Endovascular Procedures. Circulation. 2022 Jun 14;145(24):1808-1810; Karabulutoglu and others. Oxidative Stress and X-ray Exposure Levels-Dependent Survival and Metabolic Changes in Murine HSPCs. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Dec 22;11(1):11; Cruz-Garcia and others. Transcriptional Dynamics of DNA Damage Responsive Genes in Circulating Leukocytes during Radiotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2022 May 26;14(11):2649).

Appendix 1

CBRN incidents

CBRN incidents are rare and very large-scale events have not taken place in the UK, but the risk is considered to be increasing due to advances in technology and increased likelihood of terrorists using unconventional weapons.

Attacks could vary from small, targeted incidents, to large catastrophic events, such as the widespread dispersal of a biological agent or the detonation of an improvised nuclear device.

Chemical

Chemical agents of concern include nerve agents (organophosphorus compounds such as sarin), vesicant (blistering) agents such as mustard gas or cyanide and arsenic-based blood agents, as well as the misuse of toxic industrial chemicals.

In the UK, on 4 March 2018, an ex-Russian intelligence officer, his daughter and a police officer became seriously ill following exposure to the nerve agent Novichok. The incident occurred in the small city of Salisbury. Investigations initially focused on a pub and restaurant visited by those affected.

Members of the public who had visited the pub or restaurant at the time of the incident were advised to wash the clothes they had been wearing, wipe or wash personal items such as mobile phones or jewellery, and seal dry-clean-only clothing in plastic bags. Dry-clean-only clothing was collected and incinerated. The incident had a very significant impact on the local society and economy, with decontamination efforts continuing until March 2019.

Biological

Biological agents are organisms or toxins to harm humans, animals or plants. An example is anthrax, which can cause contamination lasting many years.

Heavy contamination of soil exists in enzootic foci in many parts of the world. Spores may be recovered many years after the last known case. Artificial contamination of Gruinard Island off the northwest coast of Scotland occurred in 1942 to 1943 caused by tests of a biological warfare bomb containing live anthrax spores. Even by 1979 spores could still be detected in a 3-hectare area of the island.

In the 1980s, the area was decontaminated by burning the vegetation and spraying with 5% formaldehyde in seawater. By 1987, the ground was declared anthrax-free. After reseeding, sheep were able to graze safely. UKHSA predecessor organisations worked closely with Defra and Ministry of Defense to achieve this outcome.

Radiological

Radiological materials are characterised by the type of ionising radiation they emit: alpha, beta, gamma or neutrons.

A high-profile related incident is the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko with polonium-210. Environmental polonium-210 contamination was found at several locations in London, including parts of 2 hospitals, several hotels, restaurants, and office buildings. At each location, risk assessments were undertaken to identify persons with significant risk of contamination with polonium-210. Those potentially exposed were actively monitored including taking samples, to assess their own exposure directly and to inform further public health actions. Urine samples from 753 people were processed. Of these, 139 measurements were above the reporting level set by our predecessor organisation for this incident of 30 mBq d-1, showing the likely presence of polonium-210 from the incident.

Nuclear

Nuclear incidents involve release of the energy resulting from a nuclear chain reaction or from the decay of the products of chain reaction such as the release from a nuclear power plant.

On 11 March 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake caused a tsunami that inundated part of the east coast of Japan causing catastrophic damage to 3 of the 4 operational reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Over the following few days, due to loss of power and cooling in the reactors, radioactive material was released into the atmosphere.

The surveillance systems of UKHSA’s processor organisation detected an increased level of radiation in the air in the UK. As a result, monitoring was increased including air, milk, water, soil and grass. Very low levels of radiation were detectable for a few weeks. Our radiations experts provide advice and support internationally.

The health protection capabilities that we need to respond to CBRN incidents are largely those required to protect health from large incidents involving hazardous materials. However, there are some specific issues that require additional planning and preparedness efforts including, staff training and awareness, adequate security clearance and the procurement, storage and deployment of countermeasures.

Appendix 2

The greatest burden of disease from exposure to chemical hazards is due to long term exposures. Chronic health effects do not subside when exposure stops and include cancer and respiratory diseases such as asthma.

Acute chemical incident summary, 2021

Chemical specialists from the Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards Directorate (RCE) were involved with the response of 815 acute chemical incidents for the period 1 January to 31 December 2021.

Important findings from the analysis of the data recorded in the online database, CRCE Incident Response Information System (CIRIS), are summarised below.

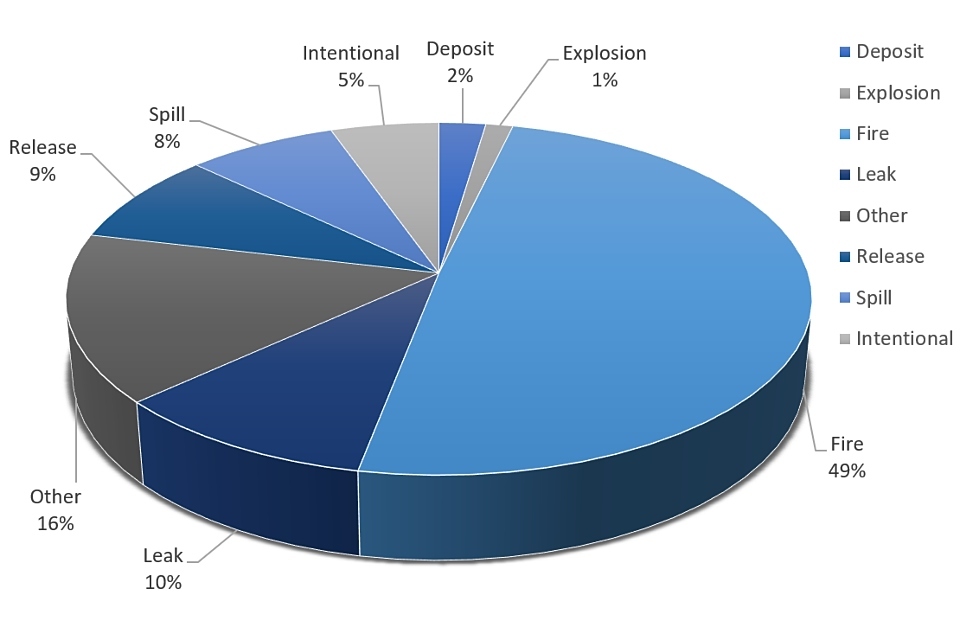

Figure 2 is a bar chart of incident types, showing that 49% (n=402) of all acute incidents in 2021 were fires.

The number of waste fires decreased from 43 in 2014 to 24 in 2021 due to RCE chemical specialists collaborating with the EA to develop plans for safer waste storage. The Fire and Rescue Services have also introduced Waste Tactical Advisors who provide advice to the waste industry when their plans are being developed.

RCE chemical specialists provide training on the Waste Tactical Advisors course to ensure that health security is considered both during the planning stage and when incidents occur.

Figure 2. Types of incidents in England in 2021 [note]

[note] Examples of ‘Other’ include odour, nuisance, air quality issues, water contamination.

In 2021, chemical specialists gave advice during the management of 3 wildfires that had the potential to affect health security. However, during the first 9 months of 2022, chemical specialists have been involved with giving advice to more than 35 wildfires.

Chemicals involved

Given that fires are the most common type of chemical incidents, it follows that products of combustion (POC) are the most commonly identified agent (51%, n=412). POC is a cocktail of toxic pollutants, hence chemical specialists provide guidance that helps to minimise public exposure and, where necessary, manage exposure.

Fatalities from chemical incidents

Thirty-six fatalities resulted from 35 incidents. The majority of the fatalities were intentional with sodium nitrate/nitrite being the causal agent. This highlighted the need for chemical specialists to continue to collaboration with the Police National CBRN Centre to further develop guidance on the management of such incidents, focusing on secondary contamination, responders and potential interment.

Population exposure to chemical incidents

It is difficult to estimate with a high degree of accuracy those who were directly exposed given that protective measures – such as sheltering indoors or, if there is an imminent risk to life, evacuation – will be implemented. Furthermore, chemical specialists provide guidance to those who were advised to shelter on how to safely vent their property to prevent the build-up of pollutants indoor, which further reduces exposure.

An estimated 288 individuals developped symptoms due to exposure to pollutants in 95 incidents. Timely advice provided by chemical specialists to Category 1 responders minimises the numbers of those who may have been exposed becoming symptomatic.

Incident location

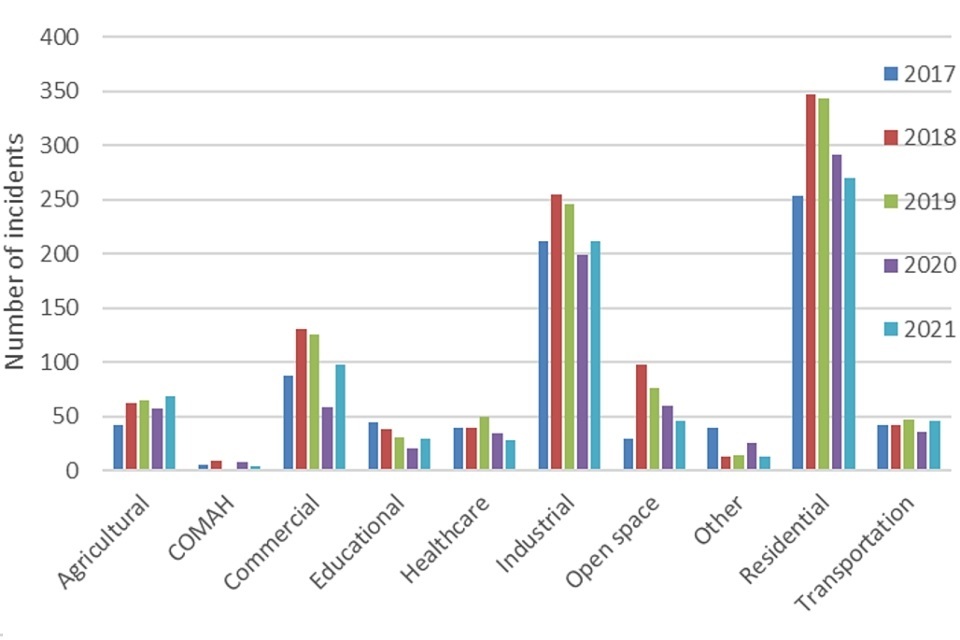

Figure 3 is a bar chart showing that in 2021, most incidents occurred in residential settings (33%, n=270) followed by industrial locations (26%, n=212). This has been the trend for a number of years and requires further investigation to ascertain whether there are inherent disparities with regards to socio-economic status of those affected.

Figure 3. Incident location trend for the period 2017 to 2021

Every year, the review of management of acute chemical incidents results in identification of gaps with regards to public health protection and sometimes highlights resources and capabilities needed to effectively and efficiently deal with these events. Tools developed as a result of the annual review, such as the mercury spill guidance for the public, have resulted in a vast reduction in the number of calls from members of the public requiring advice following a mercury spill.

In addition, in 2021, a toolkit for the management of health security issues around wildfires was developed, which was extensively tested and revised during the summer of 2022.

Appendix 3

At high doses, 4 Gray (Gy) and above, whole-body exposure to ionising radiation can be lethal. With high-quality medical care, doses of 6 to 8 Gy can be survived. High dose exposures can also lead to severe but non-fatal damage to tissues; for example, skin burns, effects on the circulatory system, nervous system, lungs and others.

Radiation exposures in the UK are well controlled and these high-level exposures only very rarely occur outside of clinical radiotherapy, the notable exception being the death of Alexander Litvinenko.

In radiotherapy, Cancer Research UK reports that 27% of cases are treated with radiotherapy, and that there are approximately 375,400 new cases per year. Typically, 5% of these radiotherapy patients develop severe normal tissue reactions, therefore over 5,000 people per year are expected to suffer such severe reactions. Lower-level exposures carry a risk of cancer and heritable effects, for which there is no dose, however low, where the risk is zero (that is, a linear non-threshold dose response model is applied).

While it is not possible to accurately assess the burden of radiation cancer in the UK population, a very rough approximation can be made. The risk of cancer following exposure is 5% per Sievert (Sv) and the average population exposure is 2.7 mSv/year (but there is significant variation on this due to medical exposures being non-random and the variation in radon concentrations in buildings around the country). On this basis, around 10,000 cancer cases would be predicted per year. More accurate information is available in the case of the burden of lung cancer due to radon exposures, and this is 1,000 cases per year.

The impact of acute radiation incidents can be demonstrated by past experiences. As a consequence of the Chornobyl accident, the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation reports 30 deaths directly from high dose exposures, and many hundreds of cases of tissue injury. Over 300,000 persons were displaced from their homes and around 6,000 additional cases of thyroid cancer occurred.

An example of a smaller scale incident is that in Goiania in Brazil, where a clinical caesium-137 source was stolen from a former hospital site. This resulted in 4 deaths. The scale of the response to such an incident is demonstrated by the number of people that had to be assessed for radiation contamination – some 112,000, of which 249 were found to be significantly contaminated.

The long-term recovery from radiation incidents takes significant time and resource. For example, the recovery from the 2011 Fukushima incident is ongoing and it is estimated that the final cost will be $15 billion.

Over many years, UKHSA staff and those of its predecessor organisations have been involved in a range of incident responses.

Windscale, UK: 1957

Although the release from the Windscale nuclear facility (now called Sellafield) occurred well before the establishment of UKHSA, the incident has been well-studied since. The response to this incident was one of the primary drivers for the creation of the National Radiological Protection Board (NRPB), a predecessor organisation to what is now UKHSA.

Three Mile Island, USA: 1979

This incident has also been well-studied.

Chornobyl, Ukraine: 1986

Extensive work was performed by our staff during the incident response and a multitude of follow-up studies, for example, work on the continuation of milk restrictions in the UK, and criteria for ending those restrictions.

Goiania, Brazil: 1986

Our staff was part of the international response to this incident in Brazil. This incident highlighted the fact that, while an event may be comparatively small, public perception of radiation risks can result in a need to monitor a large number of people for reassurance purposes (113,000 in this case).

Tokaimura, Japan: 1999

This was a criticality incident, and is interesting because there was no contamination, only irradiation.

Litvinenko, UK: 2006

Our staff was heavily involved in the response to this poisoning and contamination event. In particular, assessments of the spread of contamination in inhabited areas were performed, and criteria established for lifting restrictions; extensive monitoring activities of locations and people to assess internal exposures to polonium.

Wildfires in the Chornobyl affected area: 2010, 2020

Our staff contributed to government briefings on the consequences of fires that resuspended contamination back into the air with the potential of becoming an inhalation hazard.

Fukushima, Japan: 2011

Our staff was heavily involved in providing briefing to UK government and contributing to guidance to British nationals in Japan. Based on estimated source terms provided by the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR), working with Met Office, the Department calculated the dose consequences and potential extent of protective actions (this work lead to the development of JAM). The recovery phase of this incident has also been studied to provide input to the UK Recovery Handbook for Radiation Incidents.

Unexpected release of Ru-106: 2017

This scenario had no obvious source location and therefore Met Office (and others) explored the use of inverse modelling approaches. This is an area where development is required.

Elevated levels of radionuclides detected across Europe: 2020

The response to this event prompted BEIS to consider how UK agencies should come together to provided briefing to government when no SAGE has been set-up, and how monitoring data from overseas organisations should be collated and shared.