Country policy and information note: humanitarian situation, Ukraine, January 2025 (accessible)

Updated 28 January 2025

Version 1.0, January 2025

Executive summary

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale land, sea and air invasion of Ukraine. The war is ongoing with the heaviest fighting taking place in regions within closest proximity to the Ukraine-Russia border, together with periodic missile strikes on civilian and military infrastructure across the country.

The war is mainly concentrated in the East, Southeast and Northeast of Ukraine in the regions of Donetsk, Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Luhansk, Sumy, Dnipropetrovsk and Chernihiv.

In general, the humanitarian situation in Ukraine is not so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment as defined in paragraphs 339C and 339CA (iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Humanitarian conditions across the country vary, with Kyiv and the western oblasts experiencing comparatively better conditions than areas near the front line, where challenges are more severe. However, overall, basic needs for food, water, hygiene, shelter, and heating are being met.

Ukraine is listed as a designated state under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. However, due to the ongoing conflict, where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded.’

All cases must be considered on their individual facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate they face persecution or serious harm.

Assessment

Section updated: 27 January 2025

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

-

the humanitarian situation is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

-

internal relocation is possible to avoid persecution/serious harm

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely to be certified as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 Decision makers must also consider making an international biometric data-sharing check (see Biometric data-sharing process (Migration 5 biometric data-sharing process)).

1.1.4 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 A severe humanitarian situation does not in itself give rise to a well-founded fear of persecution for a Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.2 In the absence of a link to one of the 5 Refugee Convention grounds necessary to be recognised as a refugee, the question to address is whether the person will face a real risk of serious harm in order to qualify for Humanitarian Protection (HP).

2.1.3 However, before considering whether a person requires protection because of the general humanitarian, decision makers must consider if the person faces persecution for a Refugee Convention reason. Where the person qualifies for protection under the Refugee Convention, decision makers do not need to consider if there are substantial grounds for believing the person faces a real risk of serious harm meriting a grant of HP.

2.1.4 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds, see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status. For guidance on HP see the Asylum Instruction, Humanitarian Protection.

3. Risk

3.1.1 In general, the humanitarian situation in Ukraine is not so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment as defined in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.1.2 Humanitarian conditions across the country vary, with Kyiv and the western oblasts generally experiencing better conditions compared to areas annexed by Russia or those near the front line, where challenges are more severe. Vulnerabilities, such as age, gender, or disability may compound the risks associated with humanitarian issues, as groups like women, children, the elderly and disabled individuals can face increased challenges in accessing assistance, protection, and essential services. However overall, basic requirements for food, water, hygiene, shelter, and heating are being met. Each case must be considered on its own facts.

3.1.3 At the time of writing, the war in Ukraine is concentrated in the eastern, southeastern and northeastern parts of the country, the regions within closest proximity to Russia. However, the situation remains fluid as the conflict is ongoing. Decision makers should consult sources and tools such as ACLED’s Ukraine Conflict Monitor for ongoing and near real-time information when considering cases.

3.1.4 Whilst not country-specific to Ukraine, decision makers should note the Upper Tribunal (UT)’s findings and general approach to assessing humanitarian conditions in OA (Somalia) (CG) [2022] UKUT 33 (IAC) (2 February 2022):

‘In an Article 3 “living conditions” case, there must be a causal link between the Secretary of State’s removal decision and any “intense suffering” feared by the returnee. This includes a requirement for temporal proximity between the removal decision and any “intense suffering” of which the returnee claims to be at real risk. This reflects the requirement in Paposhvili [2017] Imm AR 867 for intense suffering to be “serious, rapid and irreversible” in order to engage the returning State’s obligations under Article 3 ECHR. A returnee fearing “intense suffering” on account of their prospective living conditions at some unknown point in the future is unlikely to be able to attribute responsibility for those living conditions to the Secretary of State, for to do so would be speculative.’ (Headnote 1)

3.1.5 On 24 February 2022 Russia launched a full-scale land, sea and air invasion of Ukraine, entering across Ukraine’s southern, eastern and northern borders. After failing to take Kyiv in the first few months, Russian attacks focused on the south and east of the country. Fighting continues along several fronts in the east of Ukraine as well as periodic missile attacks on civilian and military infrastructure across the country (see Country Policy Information Note: Ukraine Security Situation).

3.1.6 Ukraine’s economy has been severely impacted by the ongoing war, with GDP shrinking by 28.8% in 2022 and GDP per capita falling by approximately 5%. However, in 2023, the economy showed signs of recovery, growing by 5.3% and GDP per capita increasing by approximately 13%. Rural areas and the eastern regions are most impacted by the economic disruption. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has provided critical financial support to Ukraine, including a £12.5 billion loan, which has helped stabilise the economy. Banking, businesses, and public services continue to function (see Economic situation).

3.1.7 The 2022 invasion precipitated large population movements. The United Nations estimated Ukraine’s population dropped from 44.3 million in 2021 to 37.7 million in 2023, before, according to UN data, rising slightly to 38 million by September 2024. In September 2024, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) identified approximately 3.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Ukraine, mainly from the eastern oblasts. The main oblasts of origin that IDPs have fled from are Donetsk (24%), Kharkiv (20%), Kherson (12%), Zaporizhzhia (12%) and Luhansk (7%) (see Locations of origin). Most IDPs have reportedly fled to and resettled in the central-eastern oblasts of Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk and central oblast of Kyiv and its surrounding areas (see Locations of displacement).

3.1.8 In January 2025, OCHA estimated that 12.7 million people in Ukraine, including 2 million children, need humanitarian assistance. Overall, the number of people in need (PIN) has decreased by 13% from 2024, largely due to improvements in humanitarian and security conditions in Kyiv and western oblasts. Needs remain highest in the frontline areas in the east and southeast and particularly in those areas under Russian control (see People in need). Before the war, 9 million Ukrainians were living in poverty, and since the invasion, an additional 1.8 million have fallen into poverty, primarily due to job losses, bringing the total to 10.8 million. However, more than half of households are in receipt of Ukrainian social assistance including pensions and IDP allowances and external financial aid, such as the UNHCR’s cash assistance program, which has provided over £409 million to more than 2.1 million people since March 2022, helping to cater to essential needs (see Poverty).

3.1.9 In June 2023, the World Bank estimated the total cost of damage to Ukraine’s housing sector at over £39.48 billion, with eastern oblasts being the hardest hit. In 2024 they reported that more than 10% of Ukraine’s housing stock was either damaged or destroyed, affecting nearly 2 million households, with damage to housing having increased by 11% since February 2023. According to the OCHA, in 2025, an estimated 6.9 million people or 18% of the population will require shelter and non-food item (SNFI) assistance; a reduction compared with 7.9 million in 2024. These people are primarily located in the eastern crescent/front-line areas, with the regions requiring most assistance being Donetska, Kharkivka, Dnipropetrovska, Khersonska, and Mykolaivska oblasts and the western, central regions and Kyiv requiring the least (see Shelter and non-food items (SNFI)).

3.1.10 Despite damages, the UN and partners continue to operate across Ukraine, providing emergency shelter and essential services to nearly 8 million Ukrainians in 2024 alone. Support includes financial assistance, legal advice, and the installation of prefabricated homes. SNFI aid also covers repairs to homes, clothing, emergency shelters, home insulation, heating appliances and fuel. For 2025, the OCHA SNFI has allocated a budget of £437 million to continue supporting 3 million people estimated to be in need (see Shelter and non-food items (SNFI)).

3.1.11 In 2024, it was estimated that Russian airstrikes had destroyed half of Ukraine’s domestic power generation capacity, including 80% of thermal power. Damage to the electricity supply system impacted on other essential sectors such as water supply, sewage, heating, health, education and the economy (see Energy). Food insecurity persists, but in 2023 and 2024, the World Food Programme (WFP) supported 7.4 million Ukrainians by delivering food supplies, cash-based transfers and efforts to restore food systems. In 2025, the OCHA noted that 97% of the population in surveyed areas excluding frontline areas reported full availability of essential food and that there had been a 33% projected decrease in food insecurity between 2024 and 2025, from 7.5 million people to 5 million. The most affected areas continue to be in the southern, eastern, and northern oblasts, particularly in Khersonska, Zaporizka, and Donetska and which account for around 2.57 million people in need (see Food security and nutrition).

3.1.12 In 2025, OCHA reported that 97% of the Ukrainian population had access to essential hygiene products, though 8.5 million people were estimated to be in need of assistance of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) aid in 2025. The need for WASH-related aid continues to be most severe in frontline areas and those bordering Russia, with one-fifth of households experiencing constrained access to safe water. There were temporary disruptions to water supplies during 2024, particularly in areas on the front line due to Russian airstrikes. During the first nine months of 2024, around 5.8 million people were received WASH aid, mainly through repairs and emergency water supplies (see Water sanitation and hygiene (WASH)).

3.1.13 Health facilities in Ukraine have suffered targeted attacks since the start of the war. The UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission reported 478 attacks causing damage and 68 attacks destroying health facilities between 24 February 2022 and 31 July 2024 and the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported 1,680 attacks negatively impacting healthcare from the start of the war until September 2024. Aid has supported extensive work, installed electricity generators, prefabricated clinics and refurbished damaged health facilities. Between January and September 2024 Ukraine received approximately £104 million in healthcare funding which has provided healthcare support to 2 million people (see Healthcare).

3.1.14 OCHA reported that in 2025, an estimated 9.2 million people across Ukraine will require health assistance. Accessibility to services is hindered by rising costs, with 34% of households facing barriers, especially for medication and consultations. However, the projected healthcare aid budget for 2025 is just over £105 million and will seek to improve services, particularly by prioritising life-saving interventions in high-severity areas and targeting regions like the east, south, north, and Kyiv (see Healthcare).

3.1.15 The conflict has impacted the education system, with thousands of schools and educational facilities damaged or destroyed since 2022. Despite these challenges, efforts to maintain education, both online and in-person, have continued, aided by international funding. The most significant impacts to education are in areas close to the front line. The education sector continues to receive funding from the Humanitarian Response Plan which has reached 600,000 individuals with educational support so far. OCHA estimate 1.6 million children will need educational support in 2025 with a budget of £67.8 million projected to address these needs. Efforts for 2025 focus on providing safe and accessible education (see Education).

3.1.16 Humanitarian support to Ukraine continues to be coordinated through a range of international organisations and national NGOs with the Ukraine Humanitarian Fund (UHF) receiving £145.8 million in 2023. In terms of access, humanitarian aid reached 6.7 million of the 8.5 million targeted in 2024, despite increasing access challenges, mainly due to security incidents, especially near the frontlines in regions like Khersonska and Sumska (see Humanitarian aid).

3.1.17 For guidance on considering serious harm where there is a situation of indiscriminate violence in an armed conflict, including consideration of enhanced risk factors, see the Asylum Instruction, Humanitarian Protection.

4. Protection

4.1.1 The state is not able to provide protection against a breach of Article 3 because of general humanitarian conditions if this occurs in individual cases.

4.1.2 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Ukraine is the second largest country in Europe with an estimated population of 38 million and population density estimated to be 65.35 people per kilometre. It has 24 oblasts (regions), and one Autonomous Republic (Crimea) (see Geography).

5.1.2 A person is likely to be able to internally relocate because in general, there are parts of Ukraine, such as Kyiv and the surrounding region or the western oblasts furthest from direct conflict, for example Chernivitsi, Zakarpattia, Ternopil, Rivne, Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv or Volyn that are, in general safe and offer more access to essential services and humanitarian support. Each case must be considered on its facts, including the individual’s specific vulnerabilities, available resources, and the security situation (see Country Policy and Information Note on Ukraine: Security situation).

5.1.3 Since martial law was declared in February 2022, freedom of movement in Ukraine has been heavily restricted, especially for men aged 18-60 who cannot leave the country. Mandatory evacuations from frontline areas, particularly Donetska, Sumska, Kharkivska, and Khersonska oblasts, have intensified, with over 1,000 people leaving Donetska daily in September 2024. While safety concerns, lack of transport and financial barriers can impact movement, most civilians outside frontline areas report little movement restriction (see Freedom of movement).

5.1.4 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status

6. Certification

6.1.1 Ukraine is listed as a designated state under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. However, due to the ongoing conflict, where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded.’

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This section contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

The COI included was published or made publicly available on or before 27 January 2025. Any event taking place or report published after this date will not be included.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Context

7.1 Russian invasion of Ukraine

7.1.1 The current conflict in Ukraine began on 24 February 2022 when Russian military forces entered the country from Belarus, Russia and Crimea[footnote 1].

7.1.2 For a timeline of events between 2014 and 2022, see the House of Commons Library Research Briefing: Conflict in Ukraine: A timeline (2014 – eve of 2022 invasion)[footnote 2], published 22 August 2023. For a timeline of events on the current conflict from 2022, see the House of Commons Library Research Briefing: Conflict in Ukraine: A timeline (current conflict, 2022 – present) which includes events up until the briefing was published on 16 September 2024 [footnote 3].

7.1.3 See also the Home Office Country Policy and Information Note on Ukraine: Security situation, published 28 January 2025.

8. Geography

8.1 Location and size

8.1.1 Ukraine is bordered by Russia, Hungary, Romania, Moldova, Slovakia, Belarus and Poland[footnote 4].

8.1.2 Ukraine is the second largest country in Europe[footnote 5], with a total area of 603,550 square km (land: 579,330 square km and water: 24,220 square km), including areas occupied by Russia[footnote 6].

8.2 Map of Ukraine

8.2.1 Below is a United Nations (UN) map of Ukraine indicating the country’s 24 oblasts and the Autonomous republic of Crimea[footnote 7]:

8.3 Regions

8.3.1 A UK Ministry of Defence fact file paper, produced by the Permanent Committee on Geographical Names (PCGN), noted that Ukraine was divided into 27 administrative divisions, consisting of 24 oblasts (regions), one Autonomous Republic (Crimea), and 2 cities with special status (Misto Kyiv and Misto Sevastopol). The table below shows anglicised names for the administrative divisions[footnote 8]:

| Region (Romanised Ukrainian) | Anglicised name |

|---|---|

| Avtonomna Respublika Krym | Crimea |

| Cherkaska oblast | Cherkasy |

| Chernihivska oblast | Chernihiv |

| Chernivetska oblast | Chernivtsi |

| Dnipropetrovska oblast | Dnipropetrovsk |

| Donetska oblast | Donetsk |

| Ivano-Frankivska oblast | Ivano-Frankivsk |

| Kharkivska oblast | Kharkiv |

| Khersonska oblast | Kherson |

| Khmelnytska oblast | Khmelnytskyi |

| Kirovohradska oblast | Kirovohrad |

| Kyivska oblast | Kyiv |

| Luhanska oblast | Luhansk |

| Lvivska oblast | Lviv |

| Misto Kyiv | Kyiv City |

| Misto Sevastopol | Sevastopol City |

| Mykolaivska oblast | Mykolaiv |

| Odeska oblast | Odesa |

| Poltavska oblast | Poltava |

| Rivnenska oblast | Rivne |

| Sumska oblast | Sumy |

| Ternopilska oblast | Ternopil |

| Vinnytska oblast | Vinnytsia |

| Volynska oblast | Volyn |

| Zakarpatska oblast | Zakapattia |

| Zaporizka oblast | Zaporizhzhia |

| Zhytomyrska oblast | Zhytomyr |

8.3.2 In July 2024, the House of Commons Research briefing, ‘Ukraine Conflict; An Overview’ stated, ‘In early October 2022 Russia signed annexation treaties recognising Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia as part of the Russian Federation, even though those regions were not totally under Russian control.’[footnote 10]

8.3.3 The below map, published by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), shows areas of Ukraine under Russian military control, (not including Crimea), as of 22 August 2024[footnote 11]:

8.4 Population

8.4.1 Based on the 2024 UN World Population Prospects 2024, the estimated population of Ukraine was just over 38 million as of 13 September 2024, compared to 37.7 million in 2023, 41 million in 2022 and 44.3 million in 2021[footnote 12].

8.4.2 For information on population movement following the Russian invasion, see Internally displaced persons (IDPs).

8.4.3 For an estimated population per oblast (region) of Ukraine as of March 2022, see the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Ukraine Data Explorer[footnote 13].

8.4.4 As of September 2024, the World Population Review estimated Ukraine’s population density to be 65.35 people per square kilometre[footnote 14]. The US CIA observed that the ‘densest settlement [is] in the eastern (Donbas) and western regions; notable concentrations in and around major urban areas of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Donetsk, Dnipropetrovs’k, and Odesa.’[footnote 15]

8.4.5 The United Nations Population Fund estimated that as of 2024, the majority of the population (65%) was aged between 15 and 64 years, 20% were aged 65 or older and 15% were aged 0 to 14 years[footnote 16].

8.4.6 The last census was conducted in 2001[footnote 17], so available data on ethnic groups and languages spoken should be considered with this context in mind.

8.4.7 In September 2024, The US CIA World Factbook reported the populations of major urban areas in 2023 as follows:

-

Kyiv: 3,017 million

-

Kharkiv: 1.421 million

-

Odesa: 1.008 million

-

Dnipropetrovsk: 942,000

-

Donetsk: 888,000[footnote 18].

8.4.8 The same source reported:

‘Ethnic groups (2001 estimates): Ukrainian 77.8%, Russian 17.3%, Belarusian 0.6%, Moldovan 0.5%, Crimean Tatar 0.5%, Bulgarian 0.4%, Hungarian 0.3%, Romanian 0.3%, Polish 0.3%, Jewish 0.2%, other 1.8%.

‘…Languages (2001 estimates): Ukrainian (official) 67.5%, Russian (regional language) 29.6%, other (includes small Crimean Tatar-, Moldovan/Romanian-, and Hungarian-speaking minorities) 2.9%.

‘…Religion (2013 estimate): Orthodox (includes the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU), Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC), and the Ukrainian Orthodox - Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP)), Ukrainian Greek Catholic, Roman Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, Jewish[footnote 19].’

8.4.9 According to the CIA World Factbook, ‘Ukraine’s population is overwhelmingly Christian; the vast majority – up to two thirds – identify themselves as Orthodox, but many do not specify a particular branch; the OCU and the UOC-MP each represent less than a quarter of the country’s population, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church accounts for 8-10%, and the UAOC accounts for 1-2%; Muslim and Jewish adherents each compose less than 1% of the total population.’[footnote 20]

9. Areas of conflict

9.1.1 See the Country Policy and Information Note, Ukraine: Security situation.

10. Economic situation

10.1 Economic overview

10.1.1 In June 2024, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) stated, ‘Russia’s war in Ukraine continues to have a devastating economic and social impact. Skilful policymaking supported by external financing has helped maintain macroeconomic and financial stability despite challenging circumstances, and the authorities continue to advance important structural reforms. Better-than-expected growth outturns in 2023 and in 2024Q1 demonstrate the resilience of the economy.’[footnote 21]

10.1.2 In the most recently published data from the World Bank, Ukraine’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita [‘Gross domestic Product… per capita is an economic metric that breaks down a country’s economic output to a per-person allocation.’[footnote 22]], was $5,069.7 (or £4,082.9[footnote 23]) in 2023. GDP per capita had been $4,827.80 (or £3,887.66[footnote 24]) in 2021 but decreased to $4,576 (or £3,684.46[footnote 25]) in 2022, before recovering in 2023. The World Bank also reported that GDP growth was 3.4% in 2021, dropped to -28.8% in 2022, and rebounded to 5.3% in 2023. Annual inflation was reportedly 12.8% in 2023, down from 20.2% in 2022[footnote 26].

10.1.3 On 31 March 2023, the IMF approved a 4-year, ‘Extended Fund Facility’ (EFF), a $15.6 billion [£12.5 billion[footnote 27]] loan to Ukraine which was part of a $122 billion [97.76 billion[footnote 28]] total support package. The fund immediately provided about $2.7 billion [£2.16 billion[footnote 29]] to the country[footnote 30].

10.1.4 In June 2024, the IMF completed its fourth review of the EFF and approved a further payment of $2.2 billion [1.76 billion[footnote 31]] to Ukraine for budget support. It stated, ‘The economy was more resilient than expected in the first quarter of 2024, with robust growth outturns, continued disinflation, and the maintenance of adequate reserves. However, the outlook for the remainder of the year and into 2025 has worsened since the Third Review, largely due to devastating attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure and uncertainty about the length of Russia’s war against Ukraine; overall, the outlook remains subject to exceptionally high uncertainty.’[footnote 32]

10.1.5 In April 2024, the Ukraine-Third Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA3), undertaken jointly by the World Bank, the Government of Ukraine, the European Commission, and the United Nations and supported by other partners, was published, covering the period from February 2022 to December 2023. The assessment estimated the damage and losses in Ukraine along with recovery and reconstruction needs for 10 years. Note: the assessment includes a cost of reconstruction that improves on structures in place before damage. RDNA3 stated:

‘The RDNA3 follows a globally established and recognized PDNA [post-disaster needs assessment] methodology jointly developed by the World Bank, the European Union (EU), and the United Nations. This approach has been applied globally in post-disaster and war contexts to inform recovery and reconstruction planning…

‘An integral part of the assessment across all sectors is the understanding of the direct and indirect damage and loss and human impacts; application of the build back better (BBB) approach; and use of principles of green, resilient, inclusive, and sustainable recovery and reconstruction in estimating needs. Where information was available, recovery and reconstruction needs already met were deducted from the needs estimates…

‘While focusing on war-related impacts and needs, the RDNA3 contributes to and complements other ongoing efforts related to Ukraine’s reconstruction, modernization, and integration into the European community’[footnote 33]

10.1.6 The RDNA3 estimated the cost of reconstruction and recovery to be $486 billion [approximately £392 billion[footnote 34]] over the next decade[footnote 35].

10.1.7 RDNA3 stated:

‘Housing needs are the highest (over US$80 billion [£64.1 billion[footnote 36]], or 17 percent of the total), followed by transport (almost US$74 billion [£59.3 billion[footnote 37]], or 15 percent), commerce and industry (US$67.5 billion [£54.09 billion[footnote 38]], or 14 percent), agriculture (US$56 billion [£45.87 billion[footnote 39]], or 12 percent), energy (US$47 billion [£37.66 billion[footnote 40]], or 10 percent), social protection and livelihoods (US$44 billion [£35.26 billion[footnote 41]], or 9 percent), and explosive hazard management (almost US$35 billion [£28.04 billion[footnote 42]], or 7 percent).’[footnote 43]

10.1.8 On 15 January 2025, the OCHA published their Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2025 (OCHA HNRP 2025) which ‘provides a shared understanding of the impact of the war on the people of Ukraine, including the most pressing humanitarian needs’[footnote 44]. Considering the effects of the war on the economy, it noted:

‘It is estimated that the direct cost of destruction from the war could be up to US$152 billion [£122 billion[footnote 45]]. The housing sector is the most severely impacted, accounting for nearly $56 billion [£ 45.1 billion[footnote 46]], or 37 per cent of the total damage, followed by transport (about $34 billion [£27 billion[footnote 47]], or 22 per cent), commerce and industry (nearly $16 billion [£12.8 billion[footnote 48]], or 10 per cent), energy (some $11 billion [£8.8 billion[footnote 49]], or 7 per cent) and agriculture ($10 billion [£8.0 billion[footnote 50]], or 7 per cent). As of December 2023, an estimated 2 million housing units were damaged16 predominantly in Donetska, Kharkivska, Luhanska, Zaporizka, Khersonska and Kyivska oblasts. Disruptions to economic activities and production contributed to an estimated economic loss exceeding $499 billion [£399.8 billion[footnote 51]]…’[footnote 52]

10.1.9 The OCHA HNRP report 2025 noted:

‘Ukraine’s economy in 2024 remains heavily impacted by the war, with businesses and livelihood activities badly affected, particularly in regions heavily reliant on agriculture and industry. Relentless airstrikes and artillery bombardments have devastated Ukraine’s industrial hubs in the eastern regions, rendering substantial parts of the country’s economic infrastructure inoperable. In urban areas, the collapse of local economies and insecurity have forced many businesses to close, in some cases temporarily, or reduce operations.’[footnote 53]

10.1.10 The same source noted that ‘Economic recovery is projected to slow to 3.2 per cent compared to 4.8 per cent in 2023.’[footnote 54]

10.1.11 For more information on the effects of the war on the economy, see European Parliament report Two years of war: The state of the Ukrainian economy in ten charts, published February 2024.

10.2 Employment

10.2.1 The World Bank reported unemployment in Ukraine to be 9.8% in 2021[footnote 55].

10.2.2 In January 2024, in an interview for the International Labour Organisation (ILO), Oleksandr Zholud, chief economic expert at the Bank of Ukraine, explained the impact of the war on Ukraine’s labour market. He said:

‘The initial shock in February-March 2022 led to sizable drop in employment. There are data from a survey from early March that suggests that 75 per cent of small businesses halted their work. Public transport in most cities temporarily stopped working, and a massive exodus started from endangered territories. The effect was not as much a hike in unemployment but a record shrinking of the labour force. Most people who lost their jobs were unable (e.g. because public transport stopped) or unwilling (chiefly because of security concerns) to seek a new job. However, already in April 2022 the economy started recovering from the initial shock.

‘One of the main problems is that unemployment turned largely structural; a lot of production assets were destroyed, damaged or occupied, millions of people had to leave their homes and move either within Ukraine or abroad, often to the places where their skills and professions are not in demand.’[footnote 56]

10.2.3 Oleksandr Zholud went on to explain that the usual state labour force survey had not taken place since the start of the war so there was no official data on unemployment. He said, ‘the central bank used household surveys provided by the InfoSapiens research agency and other data to estimate the unemployment rate in 2022 at around 21 per cent, and expects a gradual decrease to 19 per cent in 2023.’[footnote 57]

10.2.4 The OCHA HNRP 2025 noted that, ‘While unemployment is gradually decreasing, it remains high at 11 per cent as of August 2024.’[footnote 58]

10.3 Banking system

10.3.1 In May 2024, the Kyiv Post published a brief guide to the banking sector of Ukraine. It stated, ‘Now, over two years since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s banking system still hasn’t stopped working for a day, remains resilient against numerous cyberattacks, and has become one of the few highly profitable sectors in Ukraine’s economy – contributing to it with more taxes.’[footnote 59]

10.3.2 The same source described the sector as comprising 63 banks, 6 owned by the state, 15 by foreign groups and others privately owned by Ukrainians[footnote 60].

10.3.3 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report noted:

‘A broad range of financial service providers remain, with a robust banking system serving as the main cash delivery mechanism. Improved accessibility was reported in assessed areas, including front-line locations: bank branches (63 per cent), ATMs (85 per cent) and postal service (64 per cent). Accepted payment modalities remain unchanged year-on-year: cash (100 per cent), credit cards (94-96 per cent), debit cards (75-82 per cent) and mobile apps (60-67 per cent).’[footnote 61]

11. Displaced persons

11.1 Cross-border displacement

11.1.1 From 24 February 2022 to 18 November 2024, over 40.5 million cross-border movements (not individuals) from Ukraine and over 37 million cross-border movements (not individuals) into Ukraine were recorded by the UNHCR[footnote 62].

11.1.2 The UNHCR recorded over 6.7 million ‘refugees’ (defined by UNHCR as ‘all individuals having left Ukraine due to the war’) from Ukraine as of 18 November 2024. Around 6.2 million had fled across Europe and 560,200, beyond Europe[footnote 63]. This includes over 3 million people registered for temporary protection or for similar national protection schemes. However, some people may be registered multiple times in different European states, and some may have registered in Europe and then moved onwards beyond Europe[footnote 64]. The majority of those who fled were women and children[footnote 65].

11.1.3 In February 2024, the UNHCR ‘Ukraine population movements factsheet’ noted that there were ‘more than one million monthly movements from and to Ukraine (each) during 2023.’[footnote 66]

11.1.4 In October 2024, the IOM ‘Ukraine Returns Report (URR)’ noted an estimated 4,294,000 individuals had, ‘returned to their habitual residence after a period of displacement of minimum two weeks since February 2022.’[footnote 67] Around a quarter of these returnees had returned from abroad while the others had returned from other parts of Ukraine. The numbers exclude those who returned from abroad but did not return to their normal residence[footnote 68].

11.1.5 The same report stated, ‘The highest proportion of returnees from abroad—those who were most recently displaced abroad and have since returned to their habitual residence—was found in western Ukraine, where 59% of returnees are located in the West macro-region.’[footnote 69]

11.1.6 The IOM map below, published October 2024, shows the location of returnees by oblast and proportions of people either returning from another country, another oblast or another part of their usual oblast of residence[footnote 70]:

11.2 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

a. Number of IDPs

11.2.1 In June 2024, the UNHCR ‘Global Trends: Forced displacement in 2023’ reported:

‘After the escalation of the war in 2022, displacement within and from Ukraine continued, albeit at a slower rate than during the previous year. Approximately three-quarters of a million people became newly internally displaced, primarily in eastern and southern Ukraine, where fighting was most intense during 2023. Reflecting revised estimation methodologies, as well as return movements, the number of people remaining internally displaced in Ukraine by the end of 2023 decreased to 3.7 million.’[footnote 71]

11.2.2 The same source noted, ‘The share of IDPs out of the total estimated resident population in Ukraine decreased from 12.4 per cent at the beginning of the year [2023] to 11.1 per cent at end-year.’[footnote 72]

11.2.3 UNHCR reported that over half of IDPs were female and almost a quarter were children. It stated, ‘Women and girls constituted 51 per cent of all IDPs [worldwide], with significant variations observed between countries (…as high as 58 per cent in Ukraine)’.[footnote 73]

11.2.4 It added, ‘Of note is the fact that the proportion of children among people displaced internally in Ukraine (24 per cent) is significantly higher than the proportion among the Ukrainian population as a whole (18 per cent).’[footnote 74]

11.2.5 In September 2024, IOM published Round 17 of their Ukraine Internal Displacement Report – General Population Survey, based on data from 40,000 respondents in ‘all of Ukraine, excluding the Crimean peninsula and the areas of Donetsk, Luhanska, Khersonska and Zaporizka oblasts’ between 13 July and 12 August 2024[footnote 75]

11.2.6 In the report, IOM defined IDPs as, ‘individuals who have been forced to flee or to leave their homes or who are staying outside their habitual residence in Ukraine due to the full-scale invasion in February 2022, regardless of whether they hold registered IDP status.’[footnote 76] In this context, the IOM report noted that there were approximately 3.7 million IDPs in Ukraine[footnote 77].

b. Locations of origin

11.2.7 In January 2025, the IOM Internal Displacement Report – General Population Survey, Round 19, noted that the Eastern oblasts continued to be the main origin areas of internally displaced people in Ukraine[footnote 78]. It stated, ‘Over two-thirds of IDPs (69%) originated from the Eastern macro-region, followed by the Southern macro-region (17%). Consistent with the previous rounds (R17, August 2024 and R18, October), the main oblasts of origin of IDPs were all located along or near the frontline and included areas previously or currently occupied by forces of the Russian Federation. These oblasts are the origin of 77 per cent of the total IDP population, equivalent to 2,829,000 people.’[footnote 79]

11.2.8 The table below, compiled by CPIT using IOM data, shows the estimated number of IDPs from the 10 main oblasts or regions of origin, as of January 2025[footnote 80]:

| Oblast or region of origin | Estimated number of IDPs |

|---|---|

| Donetska | 1,032,000 |

| Kharkivska | 724,000 |

| Khersonska | 439,000 |

| Zaporizka | 400,000 |

| Luhanska | 236,000 |

| Sumska | 144,000 |

| Kyiv city | 129,000 |

| Dnipropetrovska | 128,000 |

| Mykolavska | 125,000 |

| Kyivska | 85,000 |

| Other | 224,000 |

c. Locations of displacement

11.2.9 The table below, compiled by CPIT using IOM data, shows the estimated number of IDPs displaced to the 10 main oblasts or regions of displacement, as of January 2025[footnote 81]:

| Oblast or region of displacement | Estimated number of IDPs |

|---|---|

| Dnipropetrovska | 520,000 |

| Kharkivska | 447,000 |

| Kyiv city | 399,000 |

| Kyivska | 293,000 |

| Zaporizka | 233,000 |

| Odeska | 217,000 |

| Poltavska | 176,000 |

| Lvivska | 150,000 |

| Mykolavska | 122,000 |

| Cherkaska | 111,000 |

| Other | 998,000 |

11.2.10 In January 2025, the IOM Displacement Report – General Population Survey, Round 19, recorded areas that people had been displaced to. It stated:

‘One-third of IDPs (34%) resided in the Eastern macro-region, while 46 per cent of IDPs from the East resided in different oblasts within the same macro-region. The primary oblast of displacement was Dnipropetrovska Oblast, hosting 14 per cent of estimated IDPs, followed by Kharkivska Oblast (12%), Kyiv City (11%), and Kyivska Oblast (8%). Thirty-one per cent of IDPs (1,128,000 individuals) resided in frontline areas, with 38 per cent of these frontline IDPs having resided in Kharkivska Oblast.[footnote 82]

11.2.11 For nearer real-time IDP estimates and updates, see IOM’s Ukraine: Displacement Tracking Matrix and OCHA’s Ukraine Data Explorer.

11.2.12 See also the Country Policy and Information Note, Ukraine: Security situation for further information.

12. Humanitarian situation

12.1 People in need (PIN)

12.1.1 In January 2025, the OCHA HNRP 2025 report noted:

‘An estimated 12.7 million people in Ukraine need humanitarian assistance, including almost 2 million children. This includes 2.8 million IDPs and 9.9 million non-displaced people who are severely affected by the war, including returnees. The highest concentration of people in need is in the eastern, north-eastern and southern oblasts.

‘…The number of people in need in Ukraine has dropped by 13 per cent, from 14.6 million in 2024 to 12.7 million in 2025. This decline is primarily due to improved conditions in Kyiv City and Kyivska and Lvivska oblasts, which account for almost three-quarters of the 2 million reduction in people in need. Humanitarian aid and stronger socioeconomic conditions have contributed to this improvement…

‘Conversely, PiN has risen by 30 per cent in the central regions of Kirovohradska, Poltavska and Cherkaska oblasts – an estimated 895,000 people. This increase is driven by severe impacts on livelihoods, health, protection and WASH services, with urgent needs for economic support, mental health services, housing restoration and winter heating. In the west, the PiN is driven by health and WASH challenges, particularly mental health care and emergency obstetric services. In the north, east and south, protection and shelter needs dominate due to conflict-related damage to housing, limited social services and unsafe living conditions.

‘Reductions in PiN in Sumska and Kharkivska oblasts result from fewer returns to conflict areas, population decline and improved conditions for non-displaced populations. While overall needs have declined, significant humanitarian challenges persist across these regions.’[footnote 83]

12.1.2 The same source also published the below map to show PIN and the severity of needs by location in Ukraine in 2025[footnote 84]:

12.1.3 The OCHA HNRP 2025 did not specifically explain how the severity of needs (minimal – catastrophic) were measured or defined.

12.1.4 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report also considered the humanitarian impact on different groups in Ukraine:

‘The humanitarian crisis in Ukraine continues to affect various population groups in distinct ways, with war exacerbating pre-existing vulnerabilities, especially along gender, age, disability and socioeconomic lines. Each group faces unique challenges, requiring tailored interventions. Humanitarian assistance remains a lifeline for many IDPs, who report high levels of dependency (40 per cent) compared to returnees (19 per cent) and non-displaced people (13 per cent). The reliance on assistance is particularly high among returnees in Donetska (73 per cent), Khersonska (64 per cent) and Mykolaivska (37 per cent) oblasts, where the security situation severely restricts access to income-generating activities.’[footnote 85]

12.1.5 For regular updates on PIN in Ukraine, see OCHA Situation Reports.

12.2 Shelter and non-food items (SNFI)

12.2.1 In February 2024, the most recently published Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment for Ukraine, covering the period of February 2022 to December 2023 (RDNA3), reported, ‘With over 10 percent of the total housing stock either damaged or destroyed and close to 2 million households affected, housing continues to be one of the most impacted sectors. The total damage to the housing stock has increased by 11 percent since February 2023.’[footnote 86]

12.2.2 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report estimated that 6.9 million people will require SNFI in 2025[footnote 87], a decrease from the 7.9 million people projected in the OCHA HNRP 2024 report[footnote 88].

12.2.3 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report noted, ‘The ongoing war is causing the increased severity of shelter and NFI needs among Ukrainian households, particularly those residing in urban locations in front-line oblasts in the east of the country. The World Bank’s Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment report outlines that at least 10 per cent of the total housing stock in the country is damaged or destroyed. Displaced people are particularly insecure in terms of housing arrangements.’[footnote 89]

12.2.4 The map below, from the OCHA HNRP 2025 indicates the areas of Ukraine where people are in need of aid from the SNFI cluster and the assessment of severity of the needs. The map shows the most severe need near the frontline with some need over most of Ukraine with a few areas in the West having minimal need[footnote 90]:

12.2.5 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report did not specifically explain how the severity of needs (minimal – catastrophic) were measured or defined.

12.2.6 The OCHA HNRP 2024 reported, ‘The budget for the 2024 SNFI Cluster is $604.3 million [£484.2 million[footnote 91]] to assist a targeted 3.91 million people.’[footnote 92]

12.2.7 In July 2024, IOM’s ‘Ukraine Housing Brief’[footnote 93] reported on the housing situation for people living in Ukraine, including IDPs, based on responses to IOM’s General Population Survey, Round 16. For details of methodology see, page 8 of: Ukraine-Housing Brief-Living Conditions, rental costs and mobility factors- July 2024.

12.2.8 The chart below from IOM’s ‘Ukraine Housing Brief’ shows the proportion of respondents living in different types of dwelling, by displacement status, in July 2024. Most IDPs live in an apartment (53%) or a house (33%), while 8% live in a room in a house or apartment and 5% in a collective centre[footnote 94]:

12.2.9 The IOM ‘Ukraine Housing Brief’ states, ‘Security of tenure remains a critical issue, with a significant portion of IDP respondents lacking legal documents for their current tenure situation (37%). The perceived risk of eviction is also higher among IDPs, who report the highest levels of eviction experiences since the invasion began and fear of future evictions among all population groups.’[footnote 95]

12.2.10 The same source reported people in Ukraine needing to spend a high proportion of their income on rent and utilities, since the start of the war. It noted:

‘Internally displaced persons (IDPs) are particularly affected. Not only do the majority of IDPs rent their house (59%), but they are also far more likely to be unemployed and seeking work, and less likely to have a regular salary as a main source of income compared to returnees and non-displaced individuals. This protracted economic strain has forced a growing proportion of IDPs to adopt crisis coping strategies, such as skipping rent payments and moving to poorer quality housing.

‘Access to affordable housing is driving the mobility dynamics and intentions of the displaced population across Ukraine, influencing displacement, re-displacement and returns. The perceived availability of affordable housing is a significant factor influencing IDPs in selecting and residing in their location of displacement, while its lack remains a factor for them to leave their previous locations of displacement.’[footnote 96]

12.2.11 The following chart from The IOM ‘Ukraine Housing Brief’ shows monthly median household income vs housing cost, by displacement status (including cost of rent and utilities). It demonstrates that expenditure on housing was similar for the returnee, non-displaced and IDP groups but this expenditure represented a bigger proportion of the IDPs’ income because their income was smaller in comparison to the other groups[footnote 97]:

12.2.12 In September 2024, in its ‘Emergency Shelter and Housing Factsheet’ UNHCR reported on the installation of prefabricated homes. It stated:

‘For people whose homes were destroyed, UNHCR is providing Ukrainian made, prefabricated homes, installed on families’ own land, enabling them to stay or to return home if they wish to do so. These units offer a longer-term solution and provide a foundation for families to rebuild their lives and to stay within their communities. In 2023, UNHCR installed 99 core homes on land plots where the house was fully or almost fully destroyed, allowing families to return home. This year, UNHCR is currently working on the installation of 290 core homes in Central, Eastern and Southern Ukraine.’[footnote 98]

12.2.13 The Council of Europe (CoE) manages a ‘Register of Damage for Ukraine’, describing the register’s function as, ‘a record of all eligible claims seeking compensation for the damage, loss and injury inflicted…against Ukraine… Eligible claims will be recorded in the Register for future examination and evaluation.’[footnote 99] On 1 October 2024, CoE reported:

‘More than 10,000 claims have now been submitted to the Register of Damage for Ukraine (RD4U) under the category of damage or destruction of residential housing.

‘…Claims are submitted with respect to property in 621 cities, towns and villages across Ukraine, from 20 regions of Ukraine (19 Oblasts and the city of Kyiv). Claims from Donetsk Oblast (close to 35%) represent the biggest share, and Mariupol has most claims among Ukrainian cities – almost 1,150 claims’.[footnote 100]

12.2.14 In an article in November 2024, UNHCR reported that more than 74,000 IDPs were living in collective sites in November 2024 and it described improvements to accommodation provided at the sites[footnote 101].

12.2.15 The same article explained how UNHCR helps people to find longer-term accommodation. It stated:

‘UNHCR also helps find alternative and more durable housing solutions for displaced people, enabling them to move out of collective sites. Through its “Rental Market Initiative”, launched in 2023 and implemented across eight regions in central and western Ukraine, UNHCR provides protection counselling and legal advice, helps displaced people conclude rental agreements, and provides cash assistance to cover several months of rent and utilities. So far, via this programme, UNHCR has helped over 2,000 families in Ukraine find private housing solutions and facilitated their access to job opportunities, building self-reliance amongst displaced families.

‘UNHCR also supports the “Prykhystok” (Shelter) programme by providing financial assistance to host families who shelter internally displaced people across Ukraine. In 2024, UNHCR is disbursing financial support to more than 82,000 as part of the Prykhystok programme managed by the Ministry of Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine.’[footnote 102]

12.2.16 The UNHCR Ukraine: Shelter Cluster dashboard for 2024 shows the achievements of the SNFI cluster in 2024 which included providing 299,654 people with emergency shelter, 15,534 collective site refurbishments, rental support, construction materials and building repairs.

12.2.17 The IOM website states that it, ‘conducts and supports data production and research designed to guide and inform migration policy and practice.’[footnote 103] The regular summary reports on IOM’s website show estimates of how many people in Ukraine they have reached with different types of humanitarian support[footnote 104].

12.2.18 In December 2024, IOM published ‘Overall Achievements October 2024’ which estimated that as of October 2024, IOM had assisted 321,000 people through NFI support such as NFI kits and winter clothes and 154,000 people through shelter activities including repairs to houses, creation and improvement of sleeping spaces, emergency shelter support and provision of winter heating[footnote 105].

12.2.19 In December 2024, in its ‘Ukraine Delivery Updates’, UNHCR reported that between 1 January and 30 November 2024, ‘31,184 people were supported with safe access to multi-sectoral services in collective sites.’[footnote 106]

12.2.20 The same source continued, ‘…since May 2024, over 24,400 evacuees have benefitted from multi-sectoral services provided at four transit centres (Kharkiv, Izium, Pavlohrad and Kramatorsk), including 46% older people and 10% identifying as people with disabilities. In addition, over 7,900 evacuees have been accommodated in 354 collective sites since June 2024’[footnote 107]

12.2.21 In the same report, UNHCR noted that together with local authorities, they had delivered supplies including blankets and solar lamps for shelters within educational settings in both Dnipro city and in Sumska oblast[footnote 108].

12.2.22 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report noted a projected budget of $545 million (approximately £437 million[footnote 109]) to assist 3 million people in 2025[footnote 110].

12.2.23 For information on SNFI need and aid during winter months, see the November 2024 press release by the UNHCR: Winter has arrived in war-torn Ukraine: how UNHCR helps people stay warm in their homes through the cold months.

12.2.24 For more regular updates on SNFI, see OCHA Situation Reports.

12.2.25 For more information on the housing situation in Ukraine see report Ukraine-Housing Brief - Living Conditions, rental costs and mobility factors - July 2024 published by IOM in 2024.

12.3 Energy

12.3.1 The OCHA HNRP 2024 noted ‘The war has seen damage across many regions, with incidents at nuclear power plants and facilities, energy infrastructure, industrial sites and agro-processing facilities…’[footnote 111]

12.3.2 In February 2024, the World Bank RDNA3 reported, ‘The total recovery and reconstruction needs [for energy] are estimated at $47.1 billion [£37.74 billion[footnote 112]] over 10 years… This amount includes $40.4 billion [£32.37 billion[footnote 113]] necessary to rebuild the power generation sector, based on green transition principles and following the agreements with the EU, once the war ends. The regions with the largest estimated needs are Zaporizka, Kharkivska, and Donetska oblasts.’[footnote 114]

12.3.1 In June 2024, the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI), an independent research charity based in the UK[footnote 115], reported on the impact of Russian attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure:

‘Russian strikes had cumulatively destroyed 9 gigawatts (GW) of Ukraine’s domestic power generation by mid-June 2024. Peak consumption during the winter of 2023 was 18 GW, which means that half of Ukraine’s production capacity has been destroyed. At least 80% of Ukraine’s thermal power and one third of its hydroelectric power generation has been destroyed. Most recently, Russia has continued targeting the remaining hydroelectric power stations, and has even targeted the substations linked to solar farms.’[footnote 116]

12.3.2 The same source reported, ‘Most Ukrainians already experience daily blackouts, and backup power storage is common in many homes. This is manageable in the summer, but Ukraine relies on thermal power plants to generate heating for homes as well as power during its long winter months…Ukraine is already working to repair its infrastructure and to restore as much capacity as possible. However, it is estimated that there will be at least a 35% deficit in capacity come winter.’[footnote 117]

12.3.3 In June 2024, the BBC reported, ‘Russia has renewed its campaign of strikes on Ukrainian energy targets over spring and early summer, causing frequent blackouts across the country. President Volodymyr Zelensky recently said Moscow had destroyed half of his country’s electricity-generating capacity since it began pummelling its energy facilities in late March.’[footnote 118]

12.3.4 In September 2024, the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine reported further attacks on the energy infrastructure during 2024. It stated:

‘Between 22 March and 31 August 2024, the Russian Federation armed forces launched nine waves of long range and large-scale coordinated attacks on Ukraine’s electric power system, damaging or destroying numerous power generation, transmission, and distribution facilities. The strikes had reverberating effects causing harm to the civilian population and the country’s electricity supply, water distribution, sewage and sanitation systems, heating and hot water, public health, education, and the economy.

‘…The attacks have caused additional population displacement and have disproportionately impacted groups in a situation of vulnerability, such as older persons, those with disabilities, households with lower incomes, and the internally displaced, with women particularly affected. Any additional attacks will further compound this harm.’[footnote 119]

12.3.5 The same source provided information on the increasing impacts of the war damage. It stated:

‘Prior to the onset of the full scale armed attack of the Russian Federation on 24 February 2022, Ukraine produced 44.1 gigawatts of available electricity, through its nuclear, thermal, and hydroelectric power plants and renewable sources. Pre-war electricity consumption needs required approximately 26 gigawatts of electricity during winter.

‘…By the winter of 2023-2024, Ukraine could only generate around 17.8 gigawatts per hour of electricity. That winter, peak consumption reached 18.5 gigawatts per hour.

‘…While the attacks in 2022-2023 mainly targeted electricity transmission facilities, the 2024 attacks to a much larger extent targeted electricity generation facilities. According to a major energy company, the 2024 attacks damaged three times more of its TPP [Thermal Power Plant] power units than in the winter of 2022-2023.29 Attacks on hydroelectric power plants and dams also nearly tripled in 2024, according to the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine.’[footnote 120]

12.3.6 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report noted, ‘Since early 2024, nine large-scale attacks have targeted Ukraine’s energy sector, with the highest amount of energy infrastructure damaged in Dnipropetrovska, Kharkivska, Khersonska and Sumska oblasts. Rolling blackouts persist, including 12-hour outages in Kyiv…’[footnote 121]

12.3.7 For more information on the extent and impact of damage to the energy infrastructure see Sept.24-Attacks on Ukraine’s Energy Infrastructure: Harm to the Civilian Population published in September 2024 by the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine.

12.4 Food security and nutrition

12.4.1 The OCHA HNRP report 2025 noted that 97% of the population in surveyed areas reported full availability of essential food[footnote 122].

12.4.2 The same report noted:

‘In 2025, nearly 5 million people, representing 15 per cent of the population, are estimated to be food insecure and in need of food and livelihood assistance. This is a reduction of about one-third from 2024. Food insecurity remains most severe in 10 of the most affected southern, eastern and northern oblasts, with the highest number of food-insecure people in Khersonska (55 per cent), Zaporizka (42 per cent) and Donetska (39 per cent). All ten oblasts account for approximately 2.57 million people in need. The destruction of critical infrastructure and collapse of essential services, coupled with widespread displacement and economic impacts, have drastically reduced people’s ability to access food, sustain livelihoods, maintain agricultural production and afford basic food necessities. Food needs are most severe in the areas closest to the front line or active hostilities, where people lack access to functioning markets, income and critical services…’[footnote 123]

12.4.3 The World Food Programme (WFP) live HungerMap provides near real-time updates on food security and nutrition, based on ‘key metrics from various data sources – such as food security information, weather, population size, conflict, hazards, nutrition information and macro-economic data – to help assess, monitor and predict the magnitude and severity of hunger in near real-time.’[footnote 124]

12.4.4 On 26 January 2025, the WFP Hunger Map indicated there were 2.4 million people in Ukraine with ‘insufficient food consumption’. The key to the map explains the definitions used. It states, ‘People with insufficient food consumption refers to those with poor or borderline food consumption, according to the Food Consumption Score (FCS). The Food Consumption Score (FCS) is a proxy of household’s food access…based on household’s dietary diversity, food frequency, and relative nutritional importance of different food groups.’[footnote 125]

12.4.5 The same source provides a definition of ‘poor’, ‘borderline’ and ‘acceptable’ food consumption. It states:

‘Poor food consumption: Typically refers to households that are not consuming staples and vegetables every day and never or very seldom consume protein-rich food such as meat and dairy (FCS of less than 28).

‘Borderline food consumption: Typically refers to households that are consuming staples and vegetables every day, accompanied by oil and pulses a few times a week (FCS of less than 42).

‘Acceptable food consumption: Typically refers to households that are consuming staples and vegetables every day, frequently accompanied by oil and pulses, and occasionally meat, fish and dairy (FCS greater than 42).’[footnote 126]

12.4.6 The WFP HungerMap below from 26 January 2025 showed the prevalence of insufficient food consumption in frontline areas of Ukraine. The prevalence in two frontline oblasts, Donetska and Khersonska, is assessed as ‘moderately high- 20-30%’, while in six other frontline oblasts it is assessed as ‘moderately low- 10-20%’ and in Odeska as ‘low- 5-10%’[footnote 127]:

12.4.7 The OCHA HNRP report 2025 map below showed the assessment of severity of need for the food security and livelihoods cluster aid in different areas of Ukraine. The map indicated ‘severe need’ in frontline areas[footnote 128]:

12.4.8 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report did not specifically explain how the severity of needs (minimal – catastrophic) were measured or defined.

12.4.9 In October 2024, OCHA reported that between January and August 2024: ‘…Food and farming supplies were distributed to nearly 2.9 million people, focusing on front-line communities…Over 600,000 people received multi-purpose cash assistance to meet emergency basic needs’. [footnote 129]

12.4.10 In January 2024, The World Food Programme (WFP) Annual Country report for 2023 (WFP Ukraine report 2023) stated:

‘The war in Ukraine severely impacted food security, disrupting global food supply chains and contaminating vast agricultural lands in Ukraine with mines and explosive remnants, causing casualties among farmers and households. The conflict led to a significant decrease in production and income for rural communities.

‘…According to the Ministry of Economy of Ukraine’s strategy for demining of agricultural lands, 470,000 hectares of agricultural land is suspected to be contaminated by explosives, which led thousands of farmers and rural households to reduce or stop food production. According to the rapid damage and needs assessment, Ukraine production decreased by 37 percent in 2022 compared to pre-war levels. Without rapid action, many households and small-scale farmers will be unable to resume cultivation, which will have a broader regional repercussion and undermine Ukraine’s ability to recover. The population’s reliance on humanitarian assistance or temporary social payments has increased due to the destruction of private houses and mine contamination.’[footnote 130]

12.4.11 The same source reported, ‘WFP helped 4.5 million war-affected vulnerable people meet their needs across its activities in Ukraine in 2023, with 90 percent of these beneficiaries residing in areas close to the frontline. Around 2 million people consistently received support every month, many relying on WFP’s assistance to fulfil their food requirements. WFP also supported the restoration of supply chains and strengthening of food systems, as well as provided services to humanitarian and development partners.’[footnote 131]

12.4.12 The WFP Ukraine 2023 report noted:

‘In the second year of war, the frontline along the east and south persisted with minimal variation. In the areas close to the frontline, more prevalence and acuteness of food insecurity are observed. Moderate to severe food insecurity affects one in five Ukrainian households, and it gets worse during the winter. The Russian-controlled areas remained inaccessible despite continued requests for humanitarian access.

‘As a result, WFP’s crisis response programmes targeted frontline areas with the most severe needs. Food was available in Ukraine, however, the quality of wheat decreased as only 25 percent is of food-grade. Physical, and economic access challenges near the frontline due to damaged infrastructure, dysfunctional markets, and destroyed livelihoods also drove the food insecurity up, as people consistently adopted negative coping strategies and increased reliance on their own food production. Groups with specific vulnerability characteristics have higher likelihood of facing food insecurity: notably, households with people living with disabilities, the elderly, single-headed households, as well as the unemployed or precariously employed.’[footnote 132]

12.4.13 The same source reported details of the beneficiaries and food aid provided. It stated that out of the total 4.5 million beneficiaries in 2023, 61% were female and 39% male. The majority of beneficiaries were residents (3,662,760) while 727, 825 were IDPs and 90,110 were returnees. Around 3 million were helped directly with food supplies (amounting to 163,399 metric tonnes) which were mainly ‘rations’, bread, wheat flour, canned meat, canned pulses, oats, pasta and vegetable oil. Around 2 million beneficiaries were given cash- based transfers (amounting to $206,306,385 [£165,171,571.71[footnote 133]]) or vouchers (total value $6,948,311 [£5,564,146.19[footnote 134]])[footnote 135].

12.4.14 For regular updates on food and financial aid, see OCHA Situation Reports.

12.5 Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)

12.5.1 The OCHA HNRP report 2025 noted that 97% of the population in surveyed areas reported full availability of essential hygiene products[footnote 136].

12.5.2 The same report indicated that there were 8.5 million people in need of assistance from the WASH cluster[footnote 137].

12.5.3 The map below from the OCHA HNRP report 2025 showed the assessment of severity of need for WASH aid in different parts of Ukraine. The most ‘severe’ needs are in frontline areas and those areas bordering Russia[footnote 138]:

12.5.4 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report did not specifically explain how the severity of needs (minimal – catastrophic) were measured or defined.

12.5.5 The same source stated, ‘Overall, one fifth of households have experienced constrained access to safe water, with over half directly associated with the war. These issues are more pronounced near the front line with frequent or prolonged interruptions in service and difficulties in making repairs due to shelling and security challenges. They are also significant in regions far from the front line where interruptions of water supply are often linked to power outages caused by hostilities.’[footnote 139]

12.5.6 In September 2024, OCHA’s update on the humanitarian impact of hostilities in Donetsk, Kharkiv and Suma Oblasts, reported, ‘Strikes on energy facilities temporarily disrupted access to electricity and water for thousands of civilians in urban centres in Donetska and Sumska oblasts.’[footnote 140]

12.5.7 The same source reported delivery of hygiene kits in these areas[footnote 141].

12.5.8 In October 2024 OCHA reported that from January to September 2024, ‘…About 5.8 million people received water, sanitation and hygiene support, primarily through system maintenance, repairs and emergency water supply.’[footnote 142]

12.5.9 For regular updates on WASH see OCHA Situation Reports.

12.6 Poverty

12.6.1 A 2023 blog post from the Kennan Institute, ‘the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia’[footnote 143], at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, a nonpartisan foreign policy research organisation based in Washington,[footnote 144] assessed how the war affected household income. It stated:

‘When refugees and internally displaced persons are included, more than 70 percent of Ukraine’s population (those who remained in country between February and July 2022) have lost income, according to the results of the fifth wave of a survey commissioned by the European Commission and conducted by the Ukrainian research company Gradus Research in partnership with the Center for Economic Recovery. Some 73 percent of Ukrainians reported a decrease in their income compared to before the war. Another 16 percent of those surveyed said that their income had not changed, with only 3 percent reporting an increase. The greatest proportion of citizens who reported a decrease in income was recorded among internally displaced persons (83 percent of IDPs) and the least among those who went abroad (61 percent).’[footnote 145]

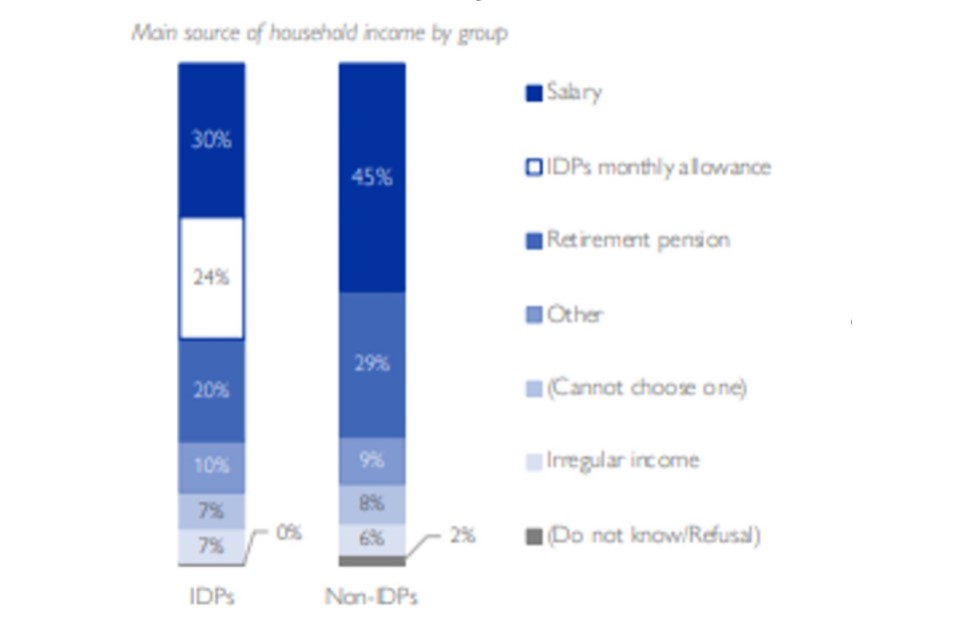

12.6.2 In January 2023, in its Internal Displacement Report, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) reported on the main sources of income for internally displaced persons (IDPs) and non-IDPs in Ukraine, based on Round 12 of the General population survey, a rapid representative assessment conducted with 2,000 respondents. The assessment, as of 23 January 2023, covered the general population across all six macro-regions – West, East, North, Centre, South, and the city of Kyiv, excluding the Crimean Peninsula.[footnote 146] For non-IDPs, ‘salary’ was the most frequently reported source, followed by ‘retirement pension’, together making up 74% of responses. For IDPs, ‘salary’ was also the most frequently reported source, followed by ‘IDPs monthly allowance’ and ‘retirement pension’ which together made up 74% of responses[footnote 147]. Main sources of income have not been considered in any subsequent reports by IOM.

12.6.3 The same IOM report included the below graph to show the main source of income for IDPs and non-IDPs, as of January 2023[footnote 148]:

12.6.4 In May 2024, the World Bank reported findings from the April to December 2023 phase of the ‘Listening to Ukraine Household Phone Surveys’ (L2Ukr), carried out in collaboration with the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. It states, ‘The L2Ukr survey involves phone interviews of between 1,500 and 2,000 households every month, initially drawing from a representative sample of the Ukrainian population in 2021 and using random digital dialing to replace households in the sample since then. This approach has made it possible to cover all parts of Ukraine currently under the government’s control.’[footnote 149]

12.6.5 The World Bank reported the following key findings:

‘The L2Ukr survey reveals that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has increased poverty, primarily due to the loss of jobs and labor income.

‘Poverty, measured according to national standards, is projected to have increased by 1.8 million people among the population remaining in Ukraine in 2023, compared to 2020. Approximately one quarter of Ukrainians, did not have enough money to buy food at some point in June 2023.

‘Declining employment drove the increase in poverty, as more than a fifth of adults employed before the war reported losing their jobs.

‘Income from social transfers such as old-age pensions and social assistance including payments to Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) accounted for just more than half of household incomes in 2023 compared to a fifth in 2021, as income from work became more uncertain and a considerable number of working-age adults migrated.

‘Sustained external financial support from donors kept old-age pensions and social assistance payments flowing, thus partly offsetting the impact of job losses on poverty. Also, a rebound in economic growth in 2023, accompanied by recovering wages and slowing inflation, helped improve food security in the second half of 2023.

‘Without continuous social transfers, especially pension payments to the elderly, almost three million more Ukrainians would have been poor.

‘Significant external funding has helped the government substantially mitigate the welfare impacts of the war…

‘97% of old-age pensions and 85% of social assistance transfers continued to be paid on time every month.

‘Benefits for Internally Displaced Persons reached the most vulnerable among them.’[footnote 150]

12.6.6 Note: the definition of ‘poverty’ by this source is as follows: ‘This is based on the official poverty line – UH 3,847.2 per adult in 2020 prices (equivalent to UH 5,220 [£99.7[footnote 151]] in 2023) – and reflects the welfare standards used for assessing poverty in the country.’[footnote 152]

12.6.7 In October 2024, the World Bank reported, ‘Poverty in Ukraine has increased by at least 1.8 million people to reach 9 million since the start of the war.’[footnote 153]

12.6.1 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report noted that, ‘Since the escalation of the war, the number of people living in poverty has increased by at least 1.8 million – with up to over 9 million people living in poverty…’[footnote 154]

12.6.2 The OCHA HNRP 2025 report noted: ‘Median monthly income dropped from 7,000 hryvna (UAH) (US$184 [or £147.28[footnote 155]]) in 2022 to UAH5,000 ($132 [or £105.65[footnote 156]]) by December 2023, with very low-income households rising from 21 to 30 per cent…’[footnote 157]

12.6.3 In August 2024, UNHCR described how ‘multi-purpose cash assistance’ was helping the people of Ukraine. It stated:

‘By offering financial support through various modalities, UNHCR empowers people to make decisions based on their specific needs and unique circumstances, preserving their dignity and independence while granting them a sense of normality and ownership. This support enables those in need to prepare for winter, pay rent, repair their homes, buy food, and live in dignified conditions. In addition, providing support via cash assistance supports the local economy.

‘…Since March 2022, UNHCR has provided cash assistance to more than 2.1 million people in Ukraine, amounting to more than USD 511 million [£409.4 million[footnote 158]]. This is possible thanks to generous funding of the European Union. The cash assistance program is implemented through a network of multi-service protection centers and mobile teams across 21 oblasts in Ukraine. These centers facilitate cash enrollment and protection screening, ensuring that aid reaches those most in need. The vulnerability criteria for eligibility are regularly updated to reflect the evolving security situation and the growing number of affected Ukrainians.’[footnote 159]

12.6.1 For more information on the economy of Ukraine and the financial effects of the war, see Economic situation.

12.6.2 The UNHCR September 2024 Cash Assistance Factsheet reported on the cash provided for different purposes in 2024:

-

Under the rental market initiative [a scheme to help IDPs to rent accommodation] around $1,830 [£1,465.43[footnote 160]] per household has been provided to 1,059 families (2,789 people), a total of $2.2 million [£1.76 million[footnote 161]] until September 2024.

-

$1 million [£ 0.8 million[footnote 162]] in total had been disbursed for Cash for repairs, between 618 families.

-

Under an agreement between UNHCR, the Ministry of Social Policy and the Pension Fund of Ukraine, as of 30 June 2024, more than 130,000 pensioners had received about $23.5 million [£18.83 million[footnote 163]] to help in covering additional energy needs[footnote 164].