UK-Australia free trade agreement: the UK's strategic approach

Updated 17 July 2020

Chapter 1: strategic case

Introduction

A free trade agreement (FTA) with Australia is part of delivering the government’s top strategic trade priority of using our voice as a new independent trading nation to champion free trade, fight protectionism and remove barriers at every opportunity. The government’s ambition is to secure FTAs covering 80% of UK trade within the next three years, to become a truly Global Britain.

More trade is essential: it can give us security at home and opportunities abroad – opening new markets for business, bringing investment, better jobs, higher wages and lower prices just as we need them most. At a time when protectionist barriers are on the rise, all countries need to work together to ensure long-term prosperity, and international trade is central to this co-operation. The UK sees accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) as an important way to combat such protectionism and an FTA with Australia as a key step towards that.

Australia is already an important partner for the UK, and an FTA offers the opportunity to strengthen this relationship. An FTA with Australia could increase UK exports to Australia by up to £900 million.[footnote 1] UK businesses traded £18.1 billion worth of goods and services with Australia in 2019[footnote 2] and boosting our trade with an FTA will aid our mutual economic recovery. We are Australia’s seventh largest trading partner and second largest outside the Asia-Pacific.[footnote 3] The UK was the second largest direct investor in Australia and the second largest recipient of Australian foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2019.[footnote 4] The stock of UK FDI in Australia was £35.6 billion in 2018, while Australia invested £15.9 billion in the UK.[footnote 5]

An FTA with Australia needs to work for the UK. We have been clear that any future agreement with Australia must work for UK consumers, producers and companies. We remain committed to upholding our high environmental, labour, food safety and animal welfare standards in our trade agreement with Australia. The government has been clear that when we are negotiating trade agreements, we will protect the National Health Service (NHS). Our objectives reinforce this.

An FTA with Australia supports the key elements of our trade strategy:

A medium-term recovery from the impact of coronavirus

Coronavirus has shown us the importance of keeping trade flowing and building diverse supply chains that are robust in a crisis. To secure our future prosperity we must now adapt and trade more with all parts of the world to ensure we are not too reliant on any one region.

An FTA between the UK and Australia will keep markets open and help diversify UK businesses’ supply chains, helping to promote resilience and ensure a sustained global economic recovery. In the face of an increase in export restrictions as a result of coronavirus, we are already working with Australia on immediate challenges, including work in the G20 to ensure supply chains continue to operate smoothly. Now, more than ever, we need to strengthen relationships with key allies to send a strong message that modern, interdependent trade is the best way to tackle global challenges. A UK-Australia FTA is an opportunity to demonstrate UK leadership in international trade as a tool to support the global economic recovery.

An FTA with a like-minded and key ally

With Australia, we share a language, a Head of State, a common law system, and societal values as well as the many family ties, friendships, and sporting rivalries. We also share a distinguished record of defence co-operation around the globe and the UK and Australia have a close intelligence and security relationship as members of ‘Five Eyes’ intelligence alliance and the Five Power Defence Arrangement. We work closely together in many multilateral fora including the United Nations, G20, World Trade Organization and the Commonwealth. A trade agreement is one of the next chapters in our shared story.

The UK and Australia also have strong and enduring people-to-people links with UK nationals accounting for the greatest number of foreign-born residents in Australia.[footnote 6] There is strong support for an FTA with Australia amongst the British public, with research[footnote 7] showing that 70% of the public support a UK-Australia FTA.[footnote 8]

For all these reasons, an FTA with Australia offers a golden opportunity to further cement our existing relationship. There are few countries with which we could negotiate as advanced an FTA as we can with Australia in the areas that matter to the UK.

Strengthening the position of UK businesses in the Asia-Pacific and moving towards joining CPTPP

Trading more with the Asia-Pacific could deliver greater prosperity for the whole of the UK. The impact of coronavirus will inevitably affect near term growth, but the Asia-Pacific remains a region with significant long-term potential.

Australia is a key partner in the Asia-Pacific. An FTA will create opportunities for the UK in this important region, be it by giving access to new supply chains or enabling UK businesses to use Australia as a launchpad into Asia.

An FTA with Australia is also a logical first step towards CPTPP membership, laying the groundwork by demonstrating the UK’s commitment to high quality and modern global trading rules.

Australia is also a leading member of CPTPP. The UK government sees joining CPTPP (one of the world’s largest free trade areas, collectively representing 13% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2018), as a key part of its economic strategy and tilt towards the Asia-Pacific. We did more than £112 billion-worth of trade in 2019 with countries in this expansive free trade area and we are determined to turbocharge our trade with these economies.[footnote 9] As an agreement that crosses the dynamic Asia-Pacific Region, CPTPP offers a crucial route to strengthen the diversity of the UK’s trading arrangements.

The UK government believes that accession to CPTPP, alongside our bilateral FTA negotiations, and wider trade policy agenda, will promote a liberal free trading agenda in the Asia-Pacific that creates an environment for long-term prosperity.

Delivering a cutting-edge agreement that creates opportunities for UK businesses, consumers, and workers

The UK and Australia produce a different mix of goods and services, suggesting that there is an opportunity to boost our mutually compatible economies by deepening our trade ties. In the long run, a UK-Australia FTA could increase UK GDP by £500 million and UK workers’ wages by £400 million.[footnote 10]

Key benefits of an FTA with Australia include:

-

Providing certainty and additional access to markets for UK services businesses by building on our similar economies, rules and systems and supporting the industries that already makes up most of our trade with Australia. Services accounted for 60% of our total exports to Australia and were worth £6.9 billion in 2019. An FTA with Australia could enhance the ability of professionals in key areas of UK strength, such as accountancy, audit and legal services, as well as engineering and architecture, to move more easily and support the facilitation of recognition of professional qualifications in priority industries such as these. For example there are opportunities for British architects, engineers and construction firms to build new railways, airports and skyscrapers across Australia, whether this is through supporting the construction of the Western Sydney International Airport, the Sydney Metro upgrade to Australia’s biggest and busiest Central Station, or Melbourne’s new housing plan. An FTA will also strengthen the existing bilateral investment relationship between Australia and the UK.

-

Reduced barriers to trade in goods, which will make trade easier and cheaper for the UK’s existing exporters to Australia, whilst at the same time benefitting UK consumers. For example, in the year to March 2019, the UK was the largest importer of Australian wine by volume,[footnote 11] while Australia imported 20 million bottles of Scotch Whisky in 2018, worth £114 million.[footnote 12]

-

Shaping the rules for digital trade in a rapidly changing world: Australia has a track record of innovation on digital trade, having recently agreed the Australia-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement (DEA).[footnote 13] An FTA with Australia provides the perfect opportunity to reduce barriers to e-commerce and stimulate investment in new technologies.

-

Strengthening our economic ties, by promoting collaboration on shared global and economic challenges. As a like-minded partner, an FTA with Australia provides an opportunity to enhance co-operation on technological change, innovation, research and development (R&D), and climate change; including the development of low carbon technologies.

-

13,400 UK SMEs (including micro enterprises and sole traders) already export goods to Australia, representing over 85% of all UK goods exporters to Australia. Yet SMEs are often disproportionately affected by barriers to trade. An ambitious and wide-ranging FTA could benefit SMEs across the country through providing clearer information, the easing of customs processes and improved conditions of entry for professionals into Australia. We will seek to reduce trade barriers that will benefit the many SMEs across the UK already exporting their goods to Australia and helping to encourage more to do so.

Creating opportunities for businesses across the nations and regions of the UK

Towns and cities across the UK are already taking advantage of global connections to succeed as competitive international businesses. In 2018, 15,300 UK businesses exported goods to Australia, employing 3.6 million people.[footnote 14]

The highest regional benefits from an UK-Australia FTA are expected to go to Scotland, the North East and the North West of England, the West Midlands, the South East and London. Opportunities for the regions and nations of the UK include:

- Reducing tariff barriers for our world class food and drink industry could bolster Scotch Whisky exports, with a third of Scotland’s exports being beverages. London businesses would also stand to benefit, since they exported over £40 million of beverages to Australia in 2019.[footnote 15]

- Medicinal and pharmaceutical products are important exports for Wales, the South East, and East of England. These regions could feel the benefits of reduced barriers to trade in these goods.

- The North West of England has recently seen a significant growth in its clothing exports and could benefit from trade liberalisation in this industry.

- Australia has an advanced financial services market and London could gain from reduced barriers to trade in financial services, which are the UK’s fifth highest services export to Australia.

- Liberalisation of Australian tariffs could benefit the Machinery and Transport equipment industry, which is the cornerstone of many regions’ exports to Australia. The automotive industry is important to the UK and Australia’s bilateral trading relationship; cars are the UK’s second highest goods export to Australia. The following regions could benefit in particular: Northern Ireland, the North East of England, the West Midlands and East of England.

The outline approach published in Chapter 2 sets out the UK’s overall objectives for these negotiations. These objectives are informed by one of the biggest consultations ever undertaken with the UK public, businesses and civil society, covering trade with the US, Australia, New Zealand, and our potential accession to the CPTPP. Our response to the consultation on Australia can be found in Chapter 3.

Chapter 2: outline approach

Overall objectives

Agree an ambitious and comprehensive free trade agreement (FTA) with Australia that strengthens our economic relationship with a key like-minded partner, promoting increased trade in goods and services and greater cross-border investment.

Strengthen our economic partnership focusing on technology, innovation and research and development (R&D). An FTA with Australia provides an opportunity to enhance co-operation on shared global and economic challenges, including supporting innovation and R&D across our economies. We will seek to set a new precedent with Australia by establishing an ambitious framework for co-operation in these areas, focusing on the role of trade policy in facilitating innovation.

Increase the resilience of our supply chains and the security of our whole economy by diversifying trade.

Futureproof the agreement in line with the government’s ambition on climate and in anticipation of rapid technological developments, such as artificial intelligence.

The government has been clear that when we are negotiating trade agreements, the National Health Service (NHS) will not be on the table. The price the NHS pays for drugs will not be on the table. The services the NHS provides will not be on the table. The NHS is not, and never will be, for sale to the private sector, whether overseas or domestic.

Secure an agreement which works for the whole of the UK and takes appropriate consideration of the UK’s constitutional arrangements and obligations.

Throughout the agreement, ensure high standards and protections for UK consumers and workers and build on our existing international obligations. This will include not compromising on our high environmental protection, animal welfare and food safety standards.

Trade in goods

Goods market access

Secure broad liberalisation of tariffs on a mutually beneficial basis, taking into account UK product sensitivities, in particular for UK agriculture.

Secure comprehensive access for UK industrial and agricultural goods into the Australian market through the elimination of tariffs.

Develop simple and modern rules of origin that reflect UK industry requirements and consider existing, as well as future, supply chains supported by predictable and low-cost administrative arrangements.

Customs and trade facilitation

Secure commitments to efficient and transparent customs procedures which minimise costs and administrative burdens for businesses.

Ensure that processes are predictable at, and away from, the border.

Technical barriers to trade

Reduce technical barriers to trade by removing and preventing trade-restrictive measures in goods markets, while upholding the safety and quality of products on the UK market.

Seek arrangements to make it easier for UK manufacturers to have their products tested against Australian rules in the UK before exporting.

Promote the use of international standards, to further facilitate trade between the parties.

Sanitary and phyto-sanitary standards

Uphold the UK’s high levels of public, animal, and plant health, including food safety.

Enhance access for UK agri-food goods to the Australian market by seeking commitments to improve the timeliness and transparency of approval processes for UK goods.

Good regulatory practice and regulatory co-operation

Reduce regulatory obstacles, facilitate market access for UK businesses and investors, and improve trade flows by ensuring a transparent, predictable and stable regulatory framework to give confidence and stability to UK exporting businesses and investors.

Secure commitments to key provisions such as public consultation, use of regulatory impact assessment, retrospective review, and transparency, as well as regulatory co-operation.

Transparency

Ensure world class levels of transparency between the UK and Australia, particularly with regards to the publication of measures (such as laws and regulations) affecting trade and investment, public consultation, and the right of appropriate review of these measures.

Commit, subject to the UK’s compliance with its data protection legislation, to prompt and open information sharing between the UK and Australia by setting up regular data sharing to support understanding of the usage and effectiveness of the agreement.

Trade in services

Secure ambitious commitments from Australia on market access and fair competition for UK services exporters.

Agree best-in-class rules for all services sectors, as well as sector-specific rules, to support our world-leading services industry, including key UK export sectors such as financial services, professional and business services and transport services.

Ensure certainty for UK services exporters in their continuing access to the Australian market and transparency on Australian services regulation.

Public services

Protect the right to regulate public services, including the NHS and public service broadcasters.

Continue to ensure that decisions on how to run public services are made by governments, including the devolved administrations, and not our trade partners.

Business mobility

Increase opportunities for UK service suppliers and investors to operate in Australia by enhancing opportunities for business travel and supporting the Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications (MRPQs).

Digital trade

Secure cutting-edge provisions which maximise opportunities for digital trade across all sectors of the economy.

Include provisions that facilitate the free flow of data, whilst ensuring that the UK’s high standards of personal data protection are maintained and include provisions to prevent unjustified data localisation requirements.

Promote appropriate protections for consumers online and ensure the government maintains its ability to protect users from emerging online harms.

Support the reduction or abolition of business and consumer restrictions relating to access to the Australian digital market.

Ensure customs duties are not imposed on electronic transmissions.

Promote a world-leading eco-system for digital trade that supports businesses of all sizes across the UK.

Telecommunications

Promote fair and transparent access to the Australian telecommunications market and avoid trade distortions.

Secure greater accessibility and connectivity for UK consumers and businesses in the Australian market.

Financial services

Expand opportunities for UK financial services to ease frictions to cross-border trade and investment, complementing with co-operation on financial regulatory issues.

Investment

Agree rules that ensure fair and open competition, and address barriers to UK investment across the Australian economy.

Establish comprehensive rules which guarantee UK investors investing in Australia the same types of rights and protections they receive in the UK, including non-discriminatory treatment and ensuring that their assets are not expropriated without due process and fair compensation.

Maintain the UK’s right to regulate in the national interest and, as the government has made clear, continue to protect the NHS.

Intellectual property (IP)

Secure copyright, provisions that support UK creative industries through a balanced and effective global framework.

Secure patents, trade marks, and designs provisions that:

- protect the UK’s existing IP standards and seek an effective and balanced regime which encourages and supports innovation

- protect UK brands and design-intensive goods whilst keeping the market open to fair competition

- do not lead to increased medicines prices for the NHS

- ensure consumer access to modern technology

- are consistent with the UK’s existing international obligations, including the European Patent Convention, to which the UK is party

Secure provisions that promote the transparent and efficient administration and enforcement of IP rights, and facilitate cross-border collaboration on IP matters.

Restate the UK’s continued commitment to the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, and agreed flexibilities that support access to medicines, particularly during public health emergencies in developing countries.

Promote effective protection of UK geographical indications in a way that ensures consumers are not misled about the origins of goods while ensuring they have access to a range of products.

Competition

Provide for effective competition law and enforcement that promotes open and fair competition for UK firms at home and in Australia.

Provide for transparent and non-discriminatory competition laws, with strong procedural rights for businesses and people under investigation.

Ensure core consumer rights are protected.

Promote effective co-operation between enforcement agencies on competition and consumer protection matters.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs)

Provide for open and fair competition between commercially oriented SOEs and private businesses by preventing discrimination and unfair practices.

Secure transparency commitments on SOEs.

Ensure that UK SOEs, particularly those providing public services, can continue to operate as they do now.

Government procurement

Secure access that goes beyond the level set in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) and is based on clear and enforceable rules and standards.

Develop improved rules, where appropriate, to ensure that procurement processes are simple, fair, open, transparent and accessible for all potential suppliers in a way that supports and builds on our commitments in the WTO GPA.

Ensure appropriate regard to public interests and services, including the need to maintain existing protections for key public services, such as NHS health services.

Sustainability

Seek sustainability provisions, including on environment and climate change, that meet the ambition of both parties on these issues.

Ensure parties reaffirm their commitment to international standards on the environment, climate change and labour.

Ensure parties do not waive or fail to enforce their domestic environmental or labour protections in ways that create an artificial competitive advantage.

Include measures which allow the UK to maintain the integrity, and provide meaningful protection, of the UK’s world-leading environmental and labour standards.

Secure provisions that support and help further the government’s ambition on climate change and achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050, including promoting clean growth, trade in low carbon goods and services, supporting research and development collaboration, maintaining both parties’ right to regulate in pursuit of decarbonisation and reaffirming our respective commitments to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement.

Apply appropriate mechanisms for the implementation, monitoring and dispute resolution of environmental and labour provisions.

Anti-corruption

Secure provisions that address the trade-distorting effects of corruption on global trade and fair competition to help maintain the UK’s high standards in this area.

Ensure appropriate mechanisms for the implementation, monitoring and dispute resolution of anti-corruption provisions.

Trade and development

Seek to ensure that relevant parts of the agreement support the government’s objectives on trade and development, including through co-operation on the monitoring of, and response to, the impact of FTAs on developing countries.

Support the continued delivery of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Trade remedies

Ensure provisions support market access, uphold our WTO commitments, and are underpinned by transparency, efficiency, impartiality and proportionality.

Secure provisions which facilitate trade liberalisation while protecting against unfair trading practices.

Dispute settlement

Establish appropriate mechanisms that promote compliance with the agreement and seek to ensure that state-to-state disputes are dealt with consistently, fairly and in a cost-effective, transparent and timely manner whilst seeking predictability and certainty for businesses and stakeholders.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)

Support UK SMEs to seize the opportunities of UK-Australia trade by:

- ensuring a dedicated SME chapter to facilitate co-operation between the UK and Australia on SME issues of mutual interest

- ensuring that SMEs have easy access to the information necessary to take advantage of the trade opportunities generated by the agreement

- ensuring that throughout the agreement SME-friendly provisions are included that support businesses trading in both services and goods

Trade and women’s economic empowerment

Seek to advance women’s economic empowerment and seek co-operation on this aim.

Promote women’s ability to access the benefits of the UK-Australia agreement in recognition of the disproportionate barriers that women can face in economic participation.

General provisions

Ensure flexibility for the government to protect legitimate domestic priorities by securing adequate general exceptions to the agreement.

Provide for prompt and open information sharing between the UK and Australia, including via preference utilisation data sharing to support understanding of the usage and effectiveness of the agreement.

Seek opportunities for co-operation on issues related to economic growth, with a particular focus on services, digital innovation, R&D and the low-carbon economy.

Provide for regular review of the economic relationship between the UK and Australia and the operation of the agreement, including taking into account developments in emerging markets and technologies. Allow for the agreement to be amended when necessary.

Territorial application

Provide for application of the treaty to all four constituent nations of the UK, taking into account the effects of the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol.

Provide for further coverage of the agreement to the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories as appropriate.

Chapter 3: public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: government response

Introduction

Consultation background

On 20 July 2018, the Department for International Trade (DIT) launched a public consultation seeking views on a potential free trade agreement (FTA) with Australia. The public consultation closed on 26 October 2018 after 14 weeks.

There were 146,188 responses received in total on this consultation. 145,905 individual responses were submitted by campaigning groups, of these, 52,396 respondents included specific individual comments in addition to the campaigns’ proposed template response. The remaining 283 non-campaign respondents were categorised into five groups: 1) individuals – 122 responses (2) businesses – 39 responses (3) business associations – 69 responses (4) non-government organisations (NGO’s) – 40 responses (5) public sector bodies – 13 responses.

You can read a full breakdown of responses below, including those by specific campaign groups.

Respondents identified a wide range of priorities for a future UK-Australia FTA and their feedback was summarised and grouped according to the 15 policy areas outlined in the consultation. An additional section entitled ‘other policy issues’ was also included to cover broader comments provided.

This report sets out the government’s response to the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia. All points raised were analysed and continue to inform the government’s overall approach to our future trading relationship with Australia, including our approach to negotiating a future trade agreement. Points that might reveal the government’s negotiating position are not responded to in the government’s response. We will continue to draw on consultation responses to inform the government’s policies during negotiations with Australia.

The government is committed to pursuing a trade policy which is inclusive and transparent. Furthermore, we will continue to engage as collaboratively as possible with a wide range of stakeholders as we look ahead to commencing negotiations.

Policy response

This section contains the governments’ explanation of its policy in relation to the comments raised by respondents in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses document, outlining the government’s position on each of the 15 policy areas covered and how this has informed the negotiating objectives set out in Chapter 2.

The public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses contains a full summary of what respondents said regarding the policy areas below. Relevant page numbers for that text are included in each of the corresponding policy sections.

The policy areas are:

- tariffs

- rules of origin (RoO)

- customs procedures

- services

- digital

- product standards, regulation and certification

- sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures

- competition

- government (public) procurement

- intellectual property (IP)

- investment

- sustainability

- trade remedies[footnote 16]

- dispute settlement

- small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) policy

- other policy issues raised by respondents

| Comments raised by respondents in the ‘Summary of responses’ under alternative headings | Policy area containing the government’s response addressing the comments |

|---|---|

| Public services including the NHS, Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications (MRPQs), visas and mobility | Services |

| Product standards, product quality, levels of protection and labelling | Product standards, regulation and certification |

| Food exports | Sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures |

| Protection of industry and imports | Competition |

| Geographical indications (GIs), the disclosure of source codes, safe harbours, copyright and algorithms | Intellectual property (IP) |

| Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) | Investment |

| Human rights | Other issues raised by respondents |

During the consultation process respondents also noted that our negotiations with Australia will take place alongside forging our new relationship with the European Union (EU).

Across all sets of negotiations, we will look to maximise opportunities for the UK. The strengths and requirements of the UK economy will be a key driver of the government’s approach to both Australian and EU negotiations. The government is committed to upholding the UK’s high standards for businesses, workers and consumers.

We will continue to listen and respond to our stakeholders’ views on this as we develop both our independent trade policy and future relationship with the EU.

Tariffs

The summary of what respondents said regarding tariffs can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

Trade in goods between the UK and Australia has increased over the last 10 years, supported by low tariffs on a large number of UK and Australian exports. The government shares the view that a further reduction or removal of Australian tariffs can offer great opportunities for UK businesses.

In a UK-Australia FTA, we will seek to remove tariffs for all UK exports, making them more competitive in the Australian market. Similarly, Australia has indicated its intention to seek to reduce or remove UK tariffs on Australian exports in a UK-Australia FTA. Increased imports from Australia could provide savings and wider choice to UK consumers and cheaper inputs to UK businesses. However, concerns have also been raised about the impact of increased competition from cheaper Australian exports on the UK market, as well as on preferential access enjoyed by developing countries into the UK market. The government will therefore ensure a balanced approach to tariff negotiations that considers the best possible outcome for products where tariff liberalisation could have a significant impact.

Rules of origin (RoO)

The summary of what respondents said regarding RoO can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

RoO are a key component of any trade agreement, as they define which goods can benefit from the liberalisation achieved in the agreement. They also ensure that only goods from countries which are party to the agreement benefit from lowered tariffs.

The government shares respondents’ views that RoO need to be prioritised in an agreement with Australia. We will seek simple and modern rules that facilitate trade between the UK and Australia, while also addressing any unfair and unreasonable practices to circumvent tariffs or quotas. Equally, we will reflect UK industry requirements and consider existing (as well as opportunities for future) supply chains.

We note respondents’ concerns over the complexity and cost of administrative arrangements to comply with RoO, and particularly recognise the case for RoO which are, as far as feasible, simple and easy to understand.

Customs procedures

The summary of what respondents said regarding customs procedures can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

Ensuring that customs procedures at the border are as facilitative as possible makes importing and exporting easier. Reducing customs delays and costs could increase the ability of businesses, especially SMEs, to trade efficiently with Australia. The government recognises the views that customs procedures need to be efficient for both UK importers and exporters, and that, to ensure compliance burdens are minimised in customs, the UK should seek to be at the forefront of global customs policy and committed to reducing customs frictions.

In our negotiations with Australia, the government recognises the case for seeking efficient, predictable and transparent customs procedures that reflect the needs of UK exporters and importers, promote supply chain security and advance customs cooperation in a way that minimises compliance burdens for businesses. The government has taken note of the view that fees and charges related to customs should not act as a barrier to trade. Furthermore, comments made by respondents on the UK’s custom arrangements with the EU will be discussed as part of the UK’s future economic relationship with the EU.

Services

The summary of what respondents said regarding services can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

The UK and Australia share a common commitment to support the further global liberalisation of trade in services. A UK-Australia FTA will provide significant opportunities to both UK services exporters and suppliers. Australia was our tenth largest services export market in 2019, with services accounting for more than half of our total (goods and services) exports. The UK exported more than £6.9 billion of services to Australia in 2019.[footnote 17]

As the second largest exporter of services in the world as of 2018,[footnote 18] the government wants to ensure that UK services businesses and individuals maintain their world-leading position by seeking greater trade liberalisation across services sectors, providing certainty and improved access to Australia’s services markets. In addition, the government will seek to create and enhance opportunities in key UK export sectors identified by stakeholders, including financial services and professional business services.

The government acknowledges that some respondents highlighted the physical distance between the UK and Australia. It also notes that for some respondents this presents an opportunity to work across time zones and boost productivity.

The government recognises that facilitating temporary movement of business people is important to promoting cross-border trade in professional services between the UK and Australia. The government will aim to increase opportunities for service suppliers and investors to operate in Australia and the UK by enhancing opportunities for business people and supporting further Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications (MRPQ) whilst maintaining the UK’s high professional standards.

The government has listened to concerns on business mobility raised by UK respondents and will be looking to include business mobility with Australia in an FTA. More broadly, it should be noted that the UK government is already working to improve the travel environment in relation to business mobility, as, for example, since May 2019 eligible Australian passport holders have been able to use eGates at UK airports and Eurostar terminals, improving security and fluidity at the border for eligible business travellers.

The government recognises the significant potential to expand opportunities for UK financial services and ease frictions to trade and investment in financial services sectors highlighted by respondents. The government will seek an ambitious agreement with Australia for financial services and will consider how to promote deeper cooperation on regulatory issues and build on existing precedents of cooperation, such as the UK-Australia FinTech bridge.

The government notes the concerns from respondents on protecting UK public services under a UK-Australia FTA. The government has been clear that it will protect the UK’s right to regulate in the public interest and protect public services, including the NHS, in a future trade deal with Australia.[footnote 19]

The government’s position is definitive: the NHS is not, and never will be, for sale to the private sector, whether overseas or domestic. When we are negotiating trade agreements, the NHS will not be on the table. The price the NHS pays for drugs will not be on the table. The services the NHS provides will not be on the table. The government is fully committed to the guiding principles of the NHS – that it is universal and free at the point of need. The government will ensure that no trade agreement will alter these fundamental facts and that decisions about public services are made by the government, including the devolved administrations (DAs), not our trade partners.

Digital

The summary of what respondents said regarding digital can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

Digital trade underpins the UK economy and is vital to both services and goods exporting businesses. In recognition of this fact, the government will ensure that a future FTA with Australia includes cutting-edge digital trade provisions and builds on existing best practice to maximise opportunities across the UK economy. The UK’s digital trade provisions will aim to reduce the costs of international trade, facilitate the coordination of global value chains, reduce barriers to digital trade, and help connect businesses and consumers.[footnote 20]

The government has listened to responses from stakeholders on the desire for robust online protections for consumers, and the need for provisions to support innovation and cyber co-operation. The government also agrees that protecting an open internet is an important principle.

The government notes stakeholders’ concerns regarding data protection and privacy standards in the UK and will ensure that robust protections for personal data are maintained. The government will seek to guarantee the free flow of data and eliminate unjustified data localisation requirements. Cross-border data flows are an important facilitator of both digitally enabled and digitally delivered trade in goods and services. For example, it is estimated that more than 52% of UK services exports to Australia (approximately £2.8 billion) were delivered remotely in 2018, a large proportion of which was due to cross-border data flows.[footnote 21] Eliminating unjustified data localisation requirements further reduces costs to businesses trading overseas, which can be prohibitive for SMEs.

The government has listened to responses on the benefits of telecommunications trade for consumers and businesses, and recognises the value of ensuring more competitive market conditions for the UK telecommunications sector. The government agrees that there is value in seeking to improve market access for UK service providers to Australia.

The government recognises the key role of the UK’s audio visual (AV) and creative industries sectors to the UK economy and consumers. The UK AV sector exported £177.4 million of services to Australia in 2018,[footnote 22] while the creative industries sector exported £741.6 million of services to Australia in the same year.[footnote 23] The government notes the strong case for ensuring both world-leading sectors are supported by a UK-Australia FTA, including by ensuring the UK’s high standards are maintained and the UK’s public service broadcasting model is protected.

Product standards, regulation and certification

The summary of what respondents said regarding product standards, regulation and certification can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

One of the main barriers to international trade, especially for SMEs, comes from differences between countries in what producers need to do to show that their products are safe and effective for that market. Trade agreements can help to overcome obstacles to trade, for example through bringing together experts to scrutinise different approaches and identify where these achieve the same levels of safety and performance.

The government agrees with respondents that there are opportunities available in this area in a UK-Australia FTA, while also acknowledging that it is crucial to ensure that UK requirements for product safety and performance remain high. We further agree that there are opportunities to reduce administrative costs for UK exporters when exporting to Australia and will seek to pursue such opportunities where possible. The government will continue to ensure the safety and quality of products on sale in the UK, recognising the important role that international standards play.

The government is fully committed to upholding the UK’s high levels of consumer, worker, and environmental protections in trade agreements. The UK’s reputation for quality, safety, and performance drives demand for UK goods and is key to our long-term prosperity. The government has no intention of harming this reputation in pursuit of a trade agreement.

The UK is committed to the transparent and predictable development of regulation and will therefore seek provisions in a future FTA with Australia that ensure good regulatory practices.

Sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures

The summary of what respondents said regarding SPS can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

The government recognises respondents’ concerns about food standards and animal welfare. Now we have left the EU, the UK will decide how we set and maintain our own standards and regulations and we have been clear that we will not compromise on our high standards of food safety and animal welfare. The UK’s reputation for high quality food and agricultural products is recognised internationally and underpins our exports of these products. Any trade agreement with Australia must work for UK consumers, farmers and companies and the government will strongly defend our right to regulate in these areas in the public interest.

The government’s manifesto has made it clear that ‘in all of our trade negotiations, we will not compromise on our high environmental protection, animal welfare and food standards’.

The UK’s independent food regulators will continue to ensure that all food imports into the UK comply with those high standards. Without exception, imports into the UK will meet our stringent food safety standards - all food imports into the UK must be safe and this will not change in any future agreement. In line with responses from business, we recognise the opportunities through a trade agreement to streamline procedures for UK food exports into Australia.

Competition

The summary of what respondents said regarding competition can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

The UK and Australia are both countries with robust competition rules, which allow businesses to compete freely and fairly to the benefit of consumers. The government recognises respondents’ views that UK businesses should be protected from unfair competition. The government can see a sound case for an ambitious competition chapter that reflects and reinforces these strong regimes.

Provisions for fair, effective and transparent competition rules could underpin liberalisation of trade between the UK and Australia. The government will also seek provisions for co-operation with Australia on competition matters.

Government (public) procurement

The summary of what respondents said regarding government procurement can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

In trade agreements, the government will look to secure more extensive market access to international procurement markets, creating much greater opportunities for UK businesses. The Australian procurement market is valued at £140 billion[footnote 24] and we currently have some access under the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA), which Australia joined in 2019. Bilateral trade negotiations provide an opportunity for the government to pursue the greater UK access that stakeholders have called for. During these negotiations, the government will seek to maintain our high standards for businesses, workers, consumers and the environment.

There were some comments calling for the UK’s international procurement obligations to favour UK domestic suppliers, but the UK’s domestic regulations that apply to government procurement require contracting authorities and contracting entities to treat suppliers equally and without discrimination. These principles continue to apply now that the UK has left the EU.

The government can endeavour to maximise UK access to Australian markets via a number of routes, ensuring that a UK-Australia FTA is mutually beneficial. This is likely to include seeking additional market access commitments from Australia; addressing specific procurement trade barriers which the GPA does not already address to ensure greater access for UK businesses and ensuring that the procurement process in Australia is simple, fair, open, transparent and accessible for all potential suppliers, especially SMEs.

There were a number of comments from respondents relating to the protection of public services. The UK’s obligations under the WTO GPA do not apply to the procurement of clinical healthcare services. Furthermore, they do not apply to the procurement of goods or services indispensable for national security or defence purposes. This will not change in any future trade deal, and we will not include such procurement in a deal with Australia. Moreover, the government will ensure that any commitments in a UK-Australia FTA have regard to areas of public interest, whilst ensuring that we remain in line with our existing international commitments under the GPA. Nor will these commitments undermine our ability to maintain the high standards for goods and services that are procured for the public sector, including where these reflect environmental or safety considerations.

Intellectual property (IP)

The summary of what respondents said regarding IP can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

A balanced and effective IP regime is an essential element of a vibrant and creative economy and an effective global trading system, providing confidence and protection for investors, entrepreneurs, inventors and creators to turn new ideas and innovations into products and services, contributing to economic growth. At the same time, it ensures consumers are clear about the origins and quality of products that they buy. The UK has a balanced and effective IP regime that is widely recognised as world-leading and respondents expressed the importance of maintaining this. A UK-Australia FTA serves as an opportunity to promote this balance between rights holders, users and consumers and to continue to set global standards.

Respondents raised concerns around copyright protection in Australia, with several acknowledging the Australian government’s recently held consultation on copyright modernisation. The government agrees with some respondents’ views that the copyright framework should encourage growth and support creativity and innovation, whilst ensuring there is an appropriate balance between creators being fairly remunerated for their work and providing fair access to that content.

Several respondents called for the protection of existing UK geographical indications (GIs) through a UK-Australia FTA. The government will seek to ensure consumers are not misled about the origins or quality of a product, balanced against the need to ensure fair competition and consumer choice. The government will continue to engage with industry on how we protect UK food and drink as we consider future trade opportunities across the world, where our GI products will play an important role as exemplars of high-quality British food and drink.

With regard to the enforcement of IP, respondents identified the opportunity for the UK and Australia to become more joined up in fighting various forms of piracy. The government is committed to promoting the transparent and effective administration and enforcement of IP rights, and views this FTA as an opportunity to raise standards of IP enforcement, particularly in the digital environment.

Respondents raised concerns around the compatibility with international obligations to which the UK is already bound, such as in the European Patent Convention (EPC). The government recognises the responsibility of continuing to comply with international treaties on IP, to which it is already party, such as the EPC, when negotiating with Australia. There are clear benefits for countries seeking a trade agreement with the UK to have access to patent protection in the UK and other EPC parties through the European Patent Office (EPO).

Some respondents called for greater protection of undisclosed test data in Australia. The government is committed to ensuring adequate protection of undisclosed test data submitted during the marketing approval process for new pharmaceutical products, agri-chemicals and biologics.

The importance of access to medicine for patients both in the UK and other countries was raised by some respondents. The government understands the need for an IP regime to be effective and that it needs to support a balance between promoting research and innovation in new medicines and technology and the wider public interest. In negotiating the UK-Australia FTA, we remain committed to maintaining this balance. The UK is already committed to the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health and will continue to support it. Furthermore, the government is committed to ensuring that patients have access to the medicines they need through the NHS and that the cost of medicines remains affordable to the NHS.

Investment

The summary of what respondents said regarding Investment can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

The government recognises the importance of maintaining and increasing investment flows between the UK and Australia, which make a valuable contribution to both economies through creating jobs and increasing competition and choice for consumers. The government will ensure that the trade agreement provides legal certainty for businesses seeking to invest in Australia, through reducing barriers to investment and ensuring legal certainty.

The government has noted the responses on ensuring investors have accurate information to support investment decisions and on the need to ensure that investors can move their capital. Such provisions are consistent with international best practice and the UK will seek to ensure this in future agreements.

The government notes the views expressed on the potential inclusion of investment protection and as associated Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism. The government believes that UK investors operating in Australia should receive the same standard of treatment as Australian investors investing in the UK. The government notes the views that have been expressed on ISDS and is clear that that any legal mechanism for resolving investment disputes must reflect modern approaches, deliver fair outcomes of claims, require high ethical standards for arbitrators, and include transparent proceedings. The government will ensure that its right to regulate in the public interest continues to be protected, particularly with regard to the environment and provision of public services.

Sustainability

The summary of what respondents said regarding sustainability can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

The government is firmly committed to maintaining our high domestic standards of environmental protection, as well as to reaffirming and maintaining our commitments to international environmental standards. The responses to the consultation made clear that the public strongly shares these views. We will continue to consider how our FTAs can be used to pursue strong environmental commitments and, in particular, to support the government’s aims in the low carbon economy.

Respondents were equally clear in their desire for upholding the UK’s high labour standards and respecting our international commitments in this area. We share this desire and are committed to securing a deal that in a way promotes our own high standards and meaningful protections for workers. We will also seek, where appropriate through our FTAs, to improve protections such as the elimination of all forms of forced labour and modern slavery. Some concerns were also expressed around the impact on jobs from more trade with Australia. It is a fundamental objective of FTAs to promote growth of the economy and jobs, therein increasing opportunities for UK workers.

We will apply appropriate mechanisms for implementation and monitoring labour and environment provisions.

Trade remedies

The summary of what respondents said regarding trade remedies can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

Trade remedies act as a safety net to protect UK businesses from injury caused by unfair trading practices, such as dumping and subsidies, or injury caused by unforeseen surges in imports. The UK has developed a new trade remedies framework which will help to create fair competition for British industries so they can compete with overseas producers that benefit from unfair practices.

We recognise the respondents’ desire for the UK to promote free and fair trade in a way that is transparent, proportionate, in-line with our existing commitments in the WTO and in a way that ensures appropriate protection for industries where necessary. As a result, the UK government is committed to seek trade remedy provisions in free trade agreements which support market access, uphold our WTO commitments, and aim to ensure trading relationships encourage alignment with the key principles underpinning the new UK trade remedies regime of transparency, efficiency, impartiality and proportionality.

The UK will seek to negotiate trade remedy chapters which facilitate trade liberalisation, act as an appropriate safety net for industries threatened by import surges or unfairly traded imports.

Dispute settlement

The summary of what respondents said regarding dispute settlement can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

Dispute settlement is commonly used in reference for the formal state-to-state mechanism for resolving disputes where one or more parties consider that there has been a breach of obligations under the relevant international trade agreement and it has not been possible to resolve the dispute informally.

The government considers an effective dispute settlement mechanism to be an appropriate part of an FTA. Effective dispute settlement mechanisms give the parties and stakeholders the confidence that commitments made under the agreement can be upheld, and that any disputes will be addressed fairly and consistently.

The government recognises that respondents want a dispute settlement mechanism that is robust, transparent, and based on existing international mechanisms such as those found at the WTO and under many existing FTAs.

Some respondents stated that stakeholders should, where possible, be involved in the dispute settlement process. The government recognises the importance of this issue and is interested in engaging with stakeholders on this further. Respondents were also clear that they did not want lengthy or costly dispute settlements in a future FTA with Australia. The government recognises this and sees the case for establishing appropriate mechanisms that enable disputes to be resolved in a timely manner, while also providing predictability and certainty for businesses and stakeholders.

Small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) policy

The summary of what respondents said regarding SME’s can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

SMEs are an integral part of the UK economy. Over 99% of private sector businesses in the UK are SMEs. However, barriers to trade disproportionately affect SMEs and may even stop them from exporting altogether. The government is committed to seeking an FTA that reduces potential barriers to trade so as to benefit the 13,400 SMEs[footnote 25] that exported goods to Australia in 2018 and create opportunities for new SME exporters. The government recognises the varied needs around the opportunities and the risks for SMEs. We will want to discuss further with stakeholders on how even SMEs, including those with limited capacity to engage on trade policy issues, can best take advantage of the benefits achieved through the agreement as regards to a potential specific SME chapter and SME-friendly provisions throughout the agreement. We will also seek commitments from Australia to make information about rules relating to trade and investment more transparent and easily accessible, and to co-operate with the UK on trade issues beneficial to SMEs.

Other policy issues raised by respondents

The summary of what respondents said regarding other policy issues raised by respondents can be found in the public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia: summary of responses.

Policy explanation

Women’s economic empowerment

We recognise that gender equality is an important issue for the public. We further recognise that the distributional impacts of trade can be gendered, and that women continue to face barriers in accessing the opportunities of free trade.

The UK is committed to exploring trade policy best practice in order to develop our own approach to advancing women’s economic empowerment through trade. We will also explore opportunities with our partners to reflect this in our future FTAs. We will seek to build our evidence base on how the impacts of trade vary by gender, including by exploring options for conducting gender-focused trade analysis.

Human rights

We recognise that respondents highlighted the protection of human rights more generally as a part of their concerns. The UK has a strong history of protecting human rights and promoting our values globally and we will continue to encourage all states to uphold international human rights obligations.

Trade and development

Some respondents raised issues that specifically addressed the government’s commitment to support developing countries to reduce poverty through trade enshrined in the White Paper Preparing for our future UK trade policy.

To deliver on our public commitment to ensure our trade and development policies remain mutually reinforcing, we will assess the impacts of trade agreements on developing countries and consider measures to address risks and maximise opportunities for development.

Next steps

As we have been developing our independent UK trade policy, DIT continues to consult with stakeholders through both informal and formal mechanisms. These include dialogues with the Secretary of State for International Trade, ministers and officials.

To ensure that our new agreements and our future trade policy work for the whole of the UK and its wider UK family; Parliament, the devolved administrations (DAs), crown dependencies, overseas territories, local government, business, trade unions, civil society and the public from every part of the UK will have the opportunity to engage and contribute.

This will be delivered by:

- open public consultations, to inform our overall approach and the development of our policy objectives

- use of the Strategic Trade Advisory Group (STAG), to seek informed stakeholder insight and views on relevant trade policy matters

- use of Expert Trade Advisory Groups (ETAGs), to contribute to our policy development at a detailed technical level

- engagement outreach events across the UK nations and regions

The STAG’s principal purpose is for the government to engage with stakeholders on trade policy matters as we shape our future trade policy and realise opportunities across all nations and regions of the UK through high level strategic discussion. The STAG’s remit extends across the breadth of trade policy. Find out who are the current members of STAG.

The objective of the ETAGs is to enable the government to draw on external knowledge and expertise to ensure that the UK’s trade policy is backed up by evidence at a detailed level and is able to deliver positive outcomes for the UK. We will draw on the expertise of these groups to gather intelligence for informing the government’s policy positions.

DIT is committed to ensuring we will have appropriate mechanisms in place during negotiations to inform the government’s position. As we move forward, we will review our approach to engagement, and consider whether existing mechanisms are fit for purpose. We welcome further and ongoing feedback and input from stakeholders during this process.

The government is committed to ensuring that our trade policy is transparent and subject to appropriate parliamentary scrutiny. During negotiations, the ogvernment will publish regular updates on negotiations.

After launching negotiations, we will be working closely with our Australian partners to agree a high-quality and mutually beneficial trade agreement which furthers the UK’s key interests. Throughout this process we will reflect on the responses to the public consultation conducted in 2018 and work closely with our domestic partners, including the DAs, and stakeholders to deliver high quality agreements for the whole of the UK.

Chapter 4: scoping assessment for a bilateral free trade agreement between the United Kingdom and Australia

Summary

The Department for International Trade (DIT) is preparing for negotiations with Australia. This scoping assessment provides a preliminary assessment of the potential long run impacts of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the UK and Australia prior to the launch of negotiations.

The importance of trade and investment links between the UK and Australia

Australia is the UK’s 11th largest non-EU trading partner and 20th largest globally. Total trade between the two countries was worth £17 billion in 2018, with just under half of this being goods trade. UK exports to Australia have been on an upward trend – growing from £4.3 billion in 2000, to £11.9 billion in 2018.[footnote 26] The UK is the second largest recipient of Australian foreign direct investment, and the UK is the third largest direct investor in Australia.[footnote 27]

UK businesses and UK jobs

- In 2018, 15,300 VAT registered businesses exported goods to Australia, employing 3.6 million people. 5,600 businesses employing 3.1 million people, imported goods from Australia.

- 15,300 UK business export

- 3.6 million employees work in these businesses

Goods trade

- The UK’s largest good export to Australia is cars and trucks. The UK’s largest imported good from Australia is lead.

- £757 million car and truck exports

- £267 million lead imports

Services trade

- Personal travel is the UK’s largest export and import service to and from Australia.

- £1.2 billion personal travel exports

- £794 million personal travel imports

Source: HMRC and ONS data, 2016-2018 annual averages.

Scope to further enhance trade and investment

A UK-Australia FTA has the potential to generate benefits for the UK. Australia has removed trading barriers for other major economies, such as South Korea, the US, and members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). This means UK firms face higher barriers. An FTA provides the UK with the opportunity to remove barriers and increase opportunities for UK businesses and investors.

The aim of enhancing the UK-Australia trading and investment relationship through an FTA is supported by the public. A recent DIT survey found that 70% of UK public support the UK establishing an FTA with Australia.[footnote 28]

The potential impact of a UK-Australia FTA

International evidence suggests that FTAs can reduce the costs of trade and investment, by eliminating tariffs and reducing non-tariff measures (NTMs) and regulatory restrictions to services trade. The analysis in this scoping assessment draws on robust evidence and the best tools available for assessing the impacts of an FTA. The results should be interpreted with caution, due to inherent uncertainty, and should not be considered as an economic forecast for the UK economy.

As the final details of the negotiated FTA are not yet known, ahead of negotiations the modelling is based on two plausible scenarios representing different depths of agreement.

Scenario 1 represents substantial tariff liberalisation by the UK, full tariff liberalisation by Australia, and a 25% reduction in the levels of actionable NTMs affecting goods and regulatory restrictions to services affecting services trade between the UK and Australia.

Scenario 2 represents a deeper trade agreement, with full tariff liberalisation and a 50% reduction in actionable NTMs and regulatory restrictions to services.

The scenarios used for modelling are based upon the UK’s current tariff schedule (the EU’s ‘Common External Tariff’). Following a consultation, the UK has recently announced the UK Global Tariff (UKGT) schedule, which will apply following the end of the transition period. The estimates do not take into account the UKGT.

Coronavirus has had a major impact on most major economies. Its economic impact is expected to be highly significant for the next few years. However, the analysis of the impact of a trade agreement with Australia relates to the long-term. It is too soon to say what the lasting impacts of the pandemic will be on international trade and domestic sectors. Our analysis therefore implicitly assumes that in the long term, the UK, Australian and global economies will have recovered from the impacts of the coronavirus. At this point in time it is too early to identify whether or how the estimated impacts in this document might be affected by the current situation.

In the short term, changes in barriers to trade and investment in response to the coronavirus pandemic will affect the flow of trade, as countries take measures to address the crisis. In the longer term, the economic benefits from FTAs are driven by a sustained reduction in barriers to trade and investment, with greater benefits derived from reducing larger barriers, enabling a larger increase in trade to follow. Where barriers to trade and investment have increased in response to the coronavirus pandemic, the economic benefits from reducing barriers via an FTA could also increase, if those increases in trade and investment barriers were to be sustained in to the long term. And similarly, where barriers are reduced in response to the coronavirus pandemic, such as a reduction in tariffs on imports of medical goods, an FTA provides an opportunity to sustain those reductions and the equivalent benefits.

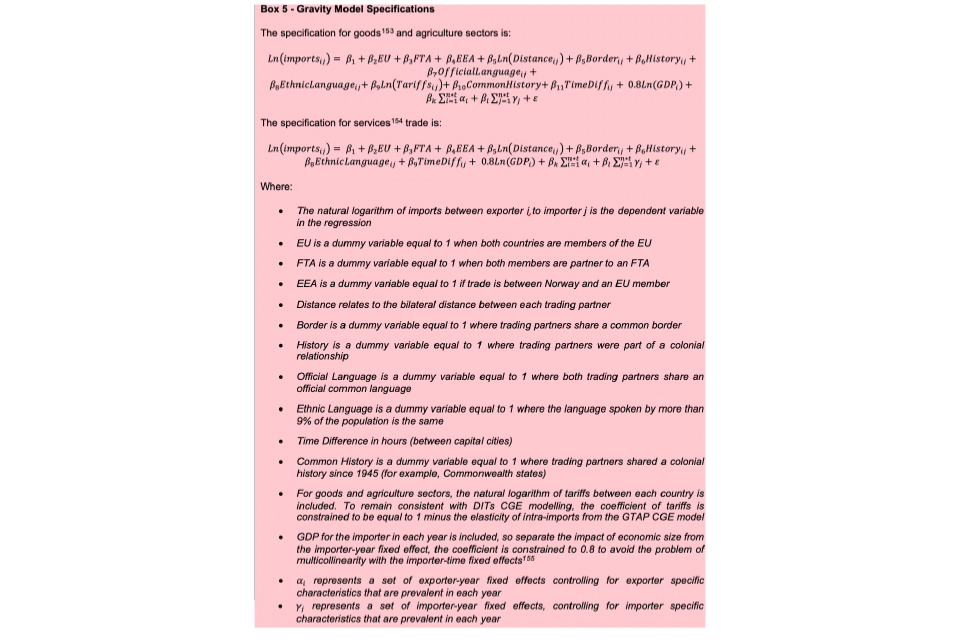

The image show scenario 1 and 2

Source: DIT modelling; central estimates for GDP impacts. £ values in 2018 terms

A trade agreement with Australia could increase UK GDP in the long run by around 0.01% or 0.02% under scenario 1 and scenario 2, respectively. This is the equivalent to an increase of £200 million or £500 million compared to its 2018 level. This increase reflects changes to the underlying economy brought about by a reduction in barriers with Australia through an FTA. These reduced costs for firms and consumers, result in changes to domestic specialisation and the composition of imports. Productivity gains are driven by resources moving to where they are more productive, including between sectors and industries, as well as between firms within sectors.

In the long run, overall UK output is estimated to increase under both scenarios, with deeper liberalisation (scenario 2) indicating higher productivity gains from further specialisation within and between sectors through the reallocation of resources to more productive firms. Increases in UK output reflect increases sectoral output across the majority of UK sectors in scenario 2. In both scenarios, productivity gains are expected to drive increases in take-home pay for workers. In the deeper liberalisation, the agriculture and semi-processed food sectors are estimated to see a fall in output and employment relative to the baseline as resources move towards expanding sectors. The reallocation of resources drive some of the overall gains from the agreement.

UK goods and services are expected to become relatively more competitive in Australia, and exports to Australia are expected to increase by 3.6% or 7.4%, depending on the scenario. Firms would be able to expand trade as the result of the reduction in trade costs on both imported inputs and exported outputs to Australia, generating productivity gains. This could also lead to an increase in the global competitiveness of UK firms, as exports to other countries outside of the agreement are also estimated to grow.

Imported goods and services from Australia facing lower trade costs could drive efficiency gains for UK businesses relying on or switching to inputs from Australia. UK consumers may also benefit if cheaper consumer goods become available. In the long run prices adjust to higher demand, but under both scenarios, imports from Australia increase by 7.3% in scenario 1 and 83.2% in scenario 2. The large increase in imports from Australia reflects assumed tariff and NTM reductions in sectors where Australian producers are relatively competitive, including categories such as semi-processed foods and agriculture.[footnote 29] Changes on imports of specific products are not modelled, but given the current pattern of UK imports of semi-processed foods from Australia, it is expected that the increase in imports would, in part, comprise sheep meat (including lamb) and bovine meat. While UK imports from Australia could increase by an estimated 83.2%, overall UK imports estimated increase by a more modest 0.1% in the long run. In 2018 UK imports from Australia were just under £5.1 billion (1% of UK total imports).

The modelling estimates an increase in the long run level of the average real wage in the UK of around 0.01% (£100 million) in scenario 1 and 0.05% (£400 million) in scenario 2.

The UK economy is expected to grow as a result of a UK-Australia FTA. Based on the distribution of sectoral value added, a scenario with less liberalisation has the potential to increase long run output across all nations and regions of the UK. Under a scenario of greater liberalisation, output may fall relative to the baseline in Northern Ireland, reflecting a higher concentration in sectors where output falls relative to the baseline.

The lowering of tariffs through a UK-Australia FTA could reduce both the price of imported consumer goods and of imported intermediate goods (used as inputs for domestic production) from Australia. Both consumers and importing businesses may directly benefit from lower tariffs, with total annual tariffs on Australian imports under the UK’s current tariff schedule, estimated to be between £32 million and £41 million per year. Non-tariff trade cost reductions can drive import prices even lower, creating further direct benefits captured in the macroeconomic analysis above.

The economic impacts of a UK-Australia FTA may have wider social and environmental implications. A preliminary assessment of the labour market impacts finds that there is no evidence to suggest that workers with protected characteristics are disproportionately concentrated in sectors where employment is estimated to fall relative to the baseline. The exception is older workers (65+), who represent 4% of the overall labour force, but represent 15% of the workers within sectors where employment falls relative to the baseline in scenario 2.

The extent to which the UK-Australia FTA impacts the environment is dependent on the negotiated outcome, which will determine changes in the pattern of trade and economic activity. Changes in the UK’s production and global trading patterns could favour UK sectors which are currently more emissions-intensive and could impact transport emissions. This government is committed to ensuring that a UK-Australia FTA will not threaten the UK’s ability to meet its environmental commitments, or its membership of international environmental agreements, and will pursue opportunities to further environmental and climate policy priorities.

Finally, GDP in Australia is estimated to increase by 0.01% or 0.06% in scenario 1 and 2, respectively, equivalent to an increase of £100 million or £700 million compared to its 2018 level, demonstrating that a UK-Australia FTA can drive economic gains for both countries.

Next steps

Following the conclusion of negotiations and once the text of a UK-Australia agreement is known, a full impact assessment will be published prior to implementation. DIT will continue to review the potential economic impacts of FTAs, and the final impact assessment will update and refine the preliminary estimates of the scale and distribution of impacts outlined in this scoping assessment.

Background

An FTA is an international agreement which seeks to increase trade and investment between its signatories by removing or reducing tariffs, NTMs and regulatory restrictions to services prohibiting trade and investment between partner countries.[footnote 30]

Trade and investment barriers make it more difficult and costlier to trade or invest overseas. By removing or reducing them, FTAs can make it easier for businesses to export, import and invest. FTAs can also benefit consumers by providing a more diverse and affordable range of imported products.

The government is committed to a transparent, inclusive and evidence-based approach to trade policy. A public consultation on a potential FTA between the UK and Australia was held between July and October 2018.

The aim of the scoping assessment is to provide Parliament and the public with a preliminary assessment of the broad scale of the potential long run impacts of an eventual FTA between the UK and Australia prior to the launch of negotiations. The content of any eventual FTA is not yet known. Once the provisions of the agreement have been negotiated, the government will publish a full impact assessment based upon the provisions of the agreement.

This scoping assessment includes the rationale for an FTA with Australia, a description of the approach used for assessing its potential impacts, the results from modelling two scenarios for a UK-Australia FTA and sensitivity analysis.

The analysis throughout the scoping assessment is based upon the UK’s current tariff schedule and does not account for the introduction of the UKGT following the end of the transition period.

The economic impact of the coronavirus is expected to be significant in the near future. It will affect both the supply and demand for goods and services and could drive significant changes to the pattern of trade between the UK and Australia. However, the analysis of the impact of a trade agreement with Australia relates to the long-term. It is too soon to say what the lasting impacts of the pandemic will be on international trade and domestic sectors. Our analysis therefore implicitly assumes that in the long term, the UK, Australian and global economies will have recovered from the impacts of the coronavirus. At this point in time it is too early to identify whether or how the estimated impacts in this document might be affected by the current situation.