Report: Understanding and tackling spiking (accessible)

Updated 30 January 2024

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 71 of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022

19 December 2023

Foreword - Laura Farris MP, Minister for Victims and Safeguarding

Spiking is an insidious and violating crime, catching its victims off-guard and often leaving them with little recall of what happened beyond the fact that they have been a victim of crime and in the worst instances, horrendous secondary offences.

In Autumn 2021, the police recorded an increase in spiking incidents, both drink spiking and a new phenomenon of needle spiking. The greatest number of incidents occurred in university towns, coinciding with Freshers’ Week and students returning to higher education following lockdown. Following the peak in Autumn 2021, the number of spiking incidents has progressively decreased. However we recognise that not all incidents of spiking are reported to the police and that true levels may be somewhat higher than current data suggests. That is why Government is taking action to tackle this crime.

Spiking can be traumatic and have long-lasting effects. For the predominantly female victims there is not only the immediate risk to their physical health, but also the shock and distress at having been targeted; the concern about going out socially in future; and, in cases of needle-facilitated spiking, the ongoing worry around testing for blood-borne diseases. We have heard of people saying spiking is being done “for a laugh” or a bit of fun – let me say now: it isn’t.

My ministerial colleagues and I have listened to victims and worked closely with the police on the nature of this threat. Whilst the offence is nominally covered by existing laws, this comprises a patchwork of different laws – some now well over a hundred years old - which were drafted to cover other kinds of offending. We consider there to be a strong case for amending the law to delineate the nature and threat of spiking and, we hope, to improve public awareness and encourage victims to come forward.

Alongside legislative amendments we bring forward, we are committed to ensuring our approach also includes a range of practical actions the government and partners will take to tackle this crime; including research into reliability of rapid drug testing kits; expanding the ways people can report spiking and improved information sources for all.

As Minister for Victims and Safeguarding, my focus is on making sure we have the laws, powers and resources in place to protect vulnerable people from harm. Spiking is as disgraceful as it is dangerous, and we are clear we will do whatever it takes to keep the public safe.

Introduction

In Autumn 2021, the police recorded an increase in spiking incidents, both drink spiking and a new phenomenon of needle spiking. The greatest number of incidents occurred in university towns, coinciding with Freshers’ Week and students returning to higher education following lockdown. Following the peak in Autumn 2021, the number of reported spiking incidents has fallen month on month. Whilst the data shows that spiking is not on the scale of previous years, we recognise that not all incidents of spiking are reported to the police. We estimate that the true level of spiking may be somewhat higher than current data but well below the volume in Autumn 2021. No one should feel unsafe on a night out, and that is why Government is taking action to tackle this crime.

Spiking, in whichever form, is a horrendous and invasive crime. While the data indicates the majority of victims are women and girls, men and boys can also be targeted. It is against the law and anyone who commits this crime faces up to ten years in prison. A victim does not need to be assaulted for it to constitute a crime. The simple act of adding something to a drink or injecting someone with a needle (without their knowledge or consent) is enough.

Alongside this report, we have launched a series of information and support pages about spiking on Gov.UK, which aim to clarify organisations’ roles and responsibilities in tackling spiking within their areas of responsibility, sets out the existing legal framework that captures this type of offending, and seeks to standardise approaches, training, and protocols. It also provides links to a range of helpful information, guidance and resources for businesses and the broader public.

The Government would like to thank all those brave victims for their contributions to this important work; they have been invaluable in developing our understanding of these crimes and in enabling us to respond more effectively.

Chapter 1: Understanding Spiking

History

In his oral evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee’s (HASC) inquiry on spiking, Michael Kill, Chair of the Night-Time Industry Association (NTIA) noted that “despite the rise in reported incidents, this has been happening for some 20 or 30 years within the industry”.[footnote 1]

But we know that spiking is by no means a new phenomenon, going back significantly further than the 20–30-year estimate; there were reports in the 1800s about the use of ‘knockout drops’ – a sedative, chloral hydrate, became known as a ‘Mickey Finn Special’; named after a bartender who used this in cocktails to sedate and subsequently steal from patrons. There is also evidence of the chemical chloroform being used in the late 19th century to incapacitate victims in order to steal their watches.[footnote 2] Chloroform has long been associated with its ability to immobilise people, given its widespread use as an anaesthetic in the UK and German-speaking countries between 1865 and 1920.[footnote 3]

The Offences against the Person Act (OAPA) was passed in Parliament in November of 1861 and brought into force one of the earliest examples of what we could refer to today as anti-spiking legislation[footnote 4]. Sections 23 and 24 of the OAPA specifically look to tackle circumstances where an individual administers a poison or any noxious substance to another person, via any method, without their consent. Recorded crime figures also show that police have been using these offences to stop criminals consistently over the years.

The following examples are within the range of behaviours that would be considered spiking, under the existing legislation:

-

Putting alcohol into someone’s drink without their knowledge or permission. This includes adding measures to someone’s drink that they have not asked for.

-

Putting prescription or illegal drugs into another person’s alcoholic or non-alcoholic drink without their knowledge or permission

-

Injecting another person with prescription or illegal drugs without their knowledge or permission

-

Putting prescription or illegal drugs into another person’s food without their knowledge or permission

-

Putting prescription or illegal drugs into another person’s cigarette or vape without their knowledge or permission.

Most experiences we know about centre on the administering of substances through “drink spiking.” So when we began hearing about a new trend of “needle spiking” in public spaces in Autumn 2021[footnote 5], there was understandable public concern and fear, particularly amongst young women. These concerns focused on the greater risk faced by young women of being spiked when on nights out and experiencing the adverse effects of such, including being at an increased level of vulnerability to further harm but also the long-term physiological impacts. The Home Secretary at the time asked the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) to urgently review the situation.

The Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC) launched an inquiry into spiking and published its report (HC 967) on 26 April 2022[footnote 6]. The Committee heard oral evidence from witnesses, received more than 50 submissions of written pieces of evidence, and issued a survey for spiking victims and witnesses. Responses were received from more than 3,000 spiking victims or witnesses.

The report included twelve recommendations for government, which fell into four themes: the scale of the problem; the legal framework; preventing and deterring spiking; and detecting and investigating spiking. Since the report was published in April 2022, government has provided several updates to the committee on general progress to tackle spiking, alongside providing updates against each recommendation.

The Home Office committed during the passage of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts (PCSC) Act 2022 to publish a report into the scale and nature of spiking and to carry out a review of the existing legislative landscape to determine whether there is a need for a new, specific criminal offence for spiking (or whether the existing laws criminalising spiking were sufficient and there were other factors at play).

This report will fulfil these commitments and set out what action government has taken, and will continue to take, to tackle this crime.

Improving our understanding

Since Autumn 2021, we have made great strides to understand and more effectively tackle spiking, as well as placing a significant focus on a victim-first approach. Our priority has been to ensure that victims have the confidence to come forward and report these crimes and that they are taken seriously when they do so.

National Police Chiefs’ Council

In response to the newly identified threat of needle spiking, and the ask of the then Home Secretary, the NPCC established a Gold Group under the name ‘Operation Lester’ to coordinate the national policing response to spiking. All police forces were required to appoint dedicated spiking leads and the NPCC organised regular meetings to collate insight, share national learning and respond to any local trends. Spiking leads were required to feed regular data on needle spiking into NPCC.

The NPCC developed a forensic strategy and worked with Eurofins Forensic Services to develop a dedicated testing process for spiking samples. This capability has enabled law enforcement to build a better understanding of what drugs are being used and how common (or not) they are in these crimes.

Forces created local investigative plans, conducted a range of spiking-related training and awareness sessions for both staff and partners, and established local partnerships to address spiking.

Operation Lester transferred across to DCC Maggie Blyth, the National Policing Lead for Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) in May 2022, recognising the importance and benefit of incorporating spiking into law enforcement’s wider work to tackle VAWG crimes and improve victim experience. At the same time, force data requirements were expanded to include all types of spiking, not just those cases where the use of a needle is reported. Work by the police to tackle spiking is ongoing, and law enforcement are looking to improve based on lessons learned.

Government review

As part of our work to understand the nature and prevalence of spiking and to help build our understanding around legislative gaps, the Home Office undertook an internal research project which included desk research, stakeholder engagement, and interviews with people with experience of current processes, including police, healthcare providers and members of the public. We also undertook a short desk-based review of how spiking was being addressed internationally.

In their report, the Home Affairs Select Committee recommended that the Home Office commission academic research into the motivations and profile of offenders, to feed into a national strategy for preventing, detecting, and prosecuting spiking offences.

Before commissioning any new research, we collaborated with Dr Amy Burrell and Professor Jessica Woodhams from the University of Birmingham and colleagues from the National Crime Agency (NCA) who conducted a systematic search of the existing research on spiking to help us understand more about perpetrator motivations.[footnote 7]

Working across government and with local partners

We established a cross-government Spiking Programme Board which sat beneath a Ministerial Roundtable chaired by the previous Minister for Safeguarding, with the core membership bringing together partners from across:

-

Home Office

-

Department for Education

-

Ministry of Justice

-

Department for Culture, Media, and Sport

-

Department for Health and Social Care

-

Other Departments and agencies, including across the Criminal Justice System (as needed)

We engaged with the Local Government Association and local authorities to understand how spiking was playing out in their communities, and action being taken to address it, to build our understanding of the crime and share good practice. We spoke to local councillors and licensing committee representatives, as well as partners in the night-time economy sector and the security industry.

Festivals and outdoor events

The Home Office worked closely with the Festivals and Outdoor events sector and the NPCC to ensure sufficient data collection, protocols, training, communications, and guidance was in place for event organisers, the police, security personnel and audiences ahead of summer events. We established weekly meetings with key stakeholders to review the situation at festivals in ‘real time’ to ensure swift responses and facilitate the sharing of learning and good practice.

What do we know now?

We have focussed much of our efforts on developing a better understanding of the problem, as well as implementing practical measures to address spiking.

Underreporting

We know that these crimes can be underreported. This can be due to a range of factors, including embarrassment, pressure from perpetrators or fear of further violence, lack of trust in the police or assumption that the police could not help, and fear of not being believed.

This means there are challenges in understanding the true prevalence, motivations of perpetrators, substances being used, and the nature of needle spiking. Spiking in all its forms is a challenging crime to assess; victims may not be aware that the effects they are experiencing are the result of being spiked. Victims may also be dealing with the trauma of a related offence, such as sexual assault, which could impact their willingness to pursue reporting the crime. The following statements were shared with us during the interviews conducted as part of our internal research:

I felt like I could have said it ‘til I was blue in the face that I was spiked but my friends would think I was too drunk […] if your friends don’t believe you, are the police going to believe you?

Victim of Spiking

I think two things I would need [to report]. I would need to be personally confident, and I would need lots of evidence. Perhaps the evidence would give me confidence.

Victim of Spiking

I’ve had history of having to report stuff to the police before. I’ve had my house broken into before. I remember that being a waste of time. I didn’t want to do it again.

Victim of Spiking

I would think of it [reporting], but I wouldn’t expect anything to come of it. You should make sure it gets logged in case it happens a lot in one club. I have 0% faith they would do an interview or look at the club CCTV or whatever it takes to get the ball rolling. It’s not the top of their list.

General Public

The police said they’ll check it out. They asked if I was aware if the pub had CCTV. I was on the phone for less than 10 minutes and it was like tick, tick, tick, going through a list, in their derogatory tone. Didn’t hear back.

Victim of Spiking

Those around a victim may also struggle to identify a spiking incident. In addition to the challenges to recognising that an incident has occurred, our interviews with participants highlighted several factors that could be contributing to underreporting particularly focused on societal and cultural challenges.

It’s really important to communicate the urgency of getting forensic tested after the incident happens. [It’s] Really unclear which substances are being used to spike victims’ drinks, and whether alcohol is playing a part in that. Even though we’re getting more data, it still feels like we don’t know enough…there are still a lot of gaps.

Police

Additionally, the perception is that victims of spiking are young, typically white, women who are in clubs in larger cities. While most victims are younger women, this image of a spiking victim can leave some feeling less likely to act if they don’t feel they fit this image.

If it happened to a female, I might have been a bit more supportive but if it was a male friend whether they were straight or gay I would have thought that they might have drunk a bit too much or taken something.

Victim of Spiking

The worry is wasting their time. I come from Zimbabwe. In Africa, police are meant to be feared. You see a police officer and you run the other way.

Victim of Spiking

Prevalence

The underreporting challenges discussed have made it difficult to truly understand the scale, nature and prevalence of this type of offending, however we do know that reports of spiking have not reached the peaks that we saw in Autumn 2021 (though we still believe that there is underreporting). We would encourage anyone who thinks they have been spiked to report as quickly as they feel able so that the Police can take immediate action.

Between May 2022 and April 2023, the police received 6,732 reports of spiking, which included 957 needle spiking reports. On average, the Police receive 561 reports a month, with the majority coming from females who believe their drink has been spiked – though spiking can affect anyone. It is important to note that needle spiking reports are significantly lower than those reported in the autumn of 2021 and the majority of reports are for drink spiking.

Analysis of the numbers of relevant spiking crimes recorded by police in England and Wales, shows a significant increase in victim reports in the fourth quarter of 2021. This followed the extensive media reporting of needle spiking incidents in September of that year.

Number of spiking reports made between January 2021 and June 2023[footnote 8]

| Apr - Jun 2023 | Jan - Mar 2023 | Oct - Dec 2022 | Jul - Sep 2022 | Apr - June 2022 | Jan - Mar 2022 | Oct - Dec 2021 | Jul - Sep 2021 | Apr - Jun 2021 | Jan - Mar 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1746 | 1813 | 2171 | 2076 | 2180 | 2790 | 4861 | 918 | 476 | 316 |

There was a clear rise in the latter part of 2021 which, once significant media attention developed, turned into a very significant rise. From the beginning of January 2022, the levels of reporting reduced significantly but remained at levels higher than prior to October 2021. Since then we have seen very steady reporting rates which are elevated from before Q3 2021. A key period was Q3 2022 where we did not see a huge increase (as in 2021).

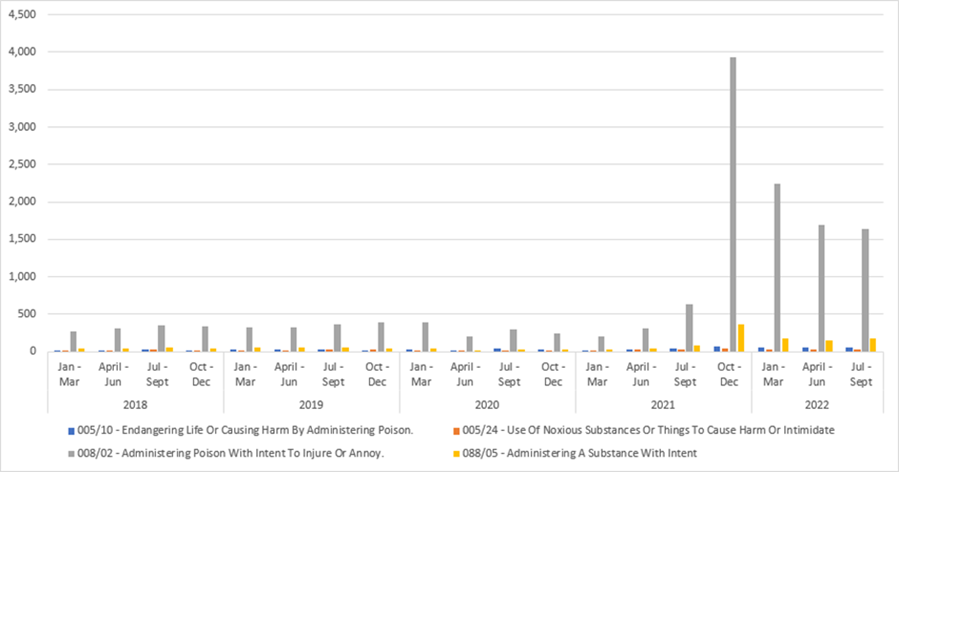

The following graph shows a fairly constant reporting level to the police between January 2018 and September 2021 for crimes that might be considered ‘spiking’ , rising significantly from October 2021. The below also highlights the four main offence codes used to capture spiking up until September 2021. The offence most commonly used by police to record this crime type is section 24 of the OAPA (offence code 008/02).

Bar chart showing the rise in 'Administering poison with intent to injure or annoy' in autumn 2021.

We believe that the current levels we are seeing more accurately reflect the true picture and result from greater consistency in police recording combined with improved victim confidence to report these crimes.

This data is echoed by that collected by NPCC. They began collecting data on needle spiking from all forces in September 2021 and that of drink and other forms of spiking from May 2022. The chart below shows the dramatic rise and peak in needle spiking incidents occurring across Autumn 2021, then dropping significantly across 2022.

Total reported spiking offences per month, Sept 21 - Oct22

| Sep 2021 | Oct 2021 | Nov 2021 | Dec 2021 | Jan 2022 | Feb 2022 | Mar 2022 | Apr 2022 | May 2022 | Jun 2022 | Jul 2022 | Aug 2022 | Sep 2022 | Oct 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drink | 376 | 462 | 459 | 431 | 380 | 502 | ||||||||

| Needle | 16 | 602 | 588 | 320 | 176 | 156 | 128 | 78 | 108 | 100 | 93 | 125 | 93 | 106 |

| Other | 71 | 58 | 40 | 24 | 17 | 13 |

Literature review

We asked the University of Birmingham and NCA team to review the available literature on spiking prevalence. Their review[footnote 9] reinforced that prevalence of this crime is difficult to measure.

Of the 87 papers reviewed, 47 included some relevant information on spiking (i.e., a substance administered covertly) but the prevalence levels varied widely from under 1% of cases to over 66% of cases.[footnote 10] The authors suggest that this is most likely to be a result of the different types of data samples used across papers. For example, samples ranged from under 100 to over 40,000 cases, some only sampled one gender or a particular age group, some only considered spiking in the context of a secondary offence, and some used as their information source toxicology reports or hospital records whereas others used survey/interview/focus group data.

The scale of the differences between samples makes meaningful comparisons across papers difficult and so the overall prevalence of spiking is difficult to determine. Another challenge identified by the review was that many researchers struggled to determine if all the cases they were analysing were spiking incidents. Even where toxicology test results were positive for a substance, without information on voluntary versus involuntary consumption of substances (including alcohol), confirming a case of spiking remains difficult. In other cases, the short half-life of some drugs could result in false negatives (i.e., someone testing negative when they were, in fact, spiked). These issues can mean that prevalence might be under- or over-estimated which adds further complications to determining genuine prevalence.

Finally, the review identified no papers that were specifically on needle spiking. There were only two references to injection as a method of administration. In summary, their overarching finding is that it is hard to determine actual levels of spiking from the existing literature and they recommend more focused research work in this area, which we will consider moving forward.

International Picture – the Global Drug Survey

The 2022 Global Drug Survey[footnote 11] (GDS) included questions to explore the experiences of people who thought their drink had been spiked. However, it is important to note that the GDS is not representative of the general population, for example, GDS respondents tend to be younger and more experienced with illicit drugs.

The survey began in mid-November 2021 and closed at the end February 2022 - over 45,000 people had taken part. 5,221 respondents completed the drink spiking section of the survey.

Most participants of that section were from the UK (24%), New Zealand (19%), Australia (16%), USA (10%), Finland (8%), and Italy (4%). In relation to drink spiking specifically, the interim findings showed that:

- 18.2% (N=951) reported that they thought their drink had ever been spiked and 1.8% (n=94) reported that they thought their drink had been spiked in the last 12 months[footnote 12].

- 50% of participants stated that spiking incidents occurred in a bar or club, 22% in a private home, 14% in a pub, 3% in a festival and 11% were other venues (e.g., college, work, concerts).

- 35% of participants declared having 5-9 drinks on the date of the spiking incident, 32% declared 3-4 drinks, 18% had 2 or less and 15% had 10 or more

- Reasons why participants suspected they had been spiked included: 50% declaring they ‘felt weird/not drunk’, 45% declared a loss of memory, 28% declared passing out, 26% declared started seeing/hearing things or generally confused, 23% declared waking up somewhere strange, 23% declared their vision or hearing ‘went weird’, and 4% felt a sharp pain/like a needle had been stuck in their body. A further 26% declared there were ‘other’ reasons as to why they suspected they had been spiked.

- 80% thought someone added a drug to their drink (excluding alcohol), 5% thought they were injected with a drug, 5% thought alcohol was added to their drink, and 15% declared having no idea. [footnote 13]

- 54% thought a stranger spiked them, 24% thought someone known to them spiked them, and 22% had no idea who had spiked them.

- 9% declared attending the hospital, 8% declared reporting to the police, and 13% declared reporting the incident to the venue.

- 14% declared being a victim of a sexual assault during the spiking incident, 2% declared being a victim of an assault (excluding sexual assault) during this incident and 84% declared not being the victim of assault during this incident.[footnote 14]

The nature of these crimes

Who is being targeted?

When it comes to spiking, young women are disproportionately affected. Data published by the NPCC in December this year shows us that almost three-quarters (74%) of all reported spiking victims are women, and that the average age of those reporting spiking (either needle or drink) is 26. [footnote 15]

However, the GDS suggests it is not just young women who report drink spiking, with 40% of the those reporting an episode in the last 12 months being male (none were gay men). This may suggest that males are less likely to report that they have been a victim of spiking to the police.

Where are these incidents happening?

Spiking takes places across a variety of location types, mostly in public spaces such as night-time economy venues (80%). NPCC data indicates that almost half of spiking incidents took place in a bar. Nightclubs were the second most common venue across both needle and non-needle spiking. Respondents to the GDS survey also indicate a bar or a club being the most common place that spiking took place.

The proportion of offences in nightclubs which featured spiking via needle was higher (38%) compared to drink spiking (17%) indicating offenders may be taking advantage of more crowded and loud venues to facilitate needle spiking offending.

A small proportion of spiking incidents took place in residential addresses, most of which were in the context of a house party. Other venues reported include Student Unions, Pubs, Restaurants as well as a Festival/Carnival, a Garage, and a Live Music Arena.

More than half of the reported incidents took place in busy town centres or locations where there was a high density of night-time economy venues.

The literature review by University of Birmingham / NCA team[footnote 16] also identified a number of contexts in which spiking occurs. Similar to the NPCC data, contexts included night-time economy / entertainment environments (including house parties), where victims were often female, and timings clustered late at night on weekend evenings. Some incidents occurred in domestic situations – for example, as part of a pattern of domestic abuse[footnote 17].

What drugs are being used?

We know that, according to NPCC data, between December 2021 and October 2023, 1261 urine samples from suspected victims of spiking had been submitted for forensic analysis.

Forensic testing has shown that 5% of those samples tested contained a controlled drug that supported a spiking incident (64 cases), and the most commonly detected drugs were cocaine, ketamine and MDMA.

The majority (52%) of samples tested contained a drug of no concern or no drug at all. A drug of no concern is one that would not have a rapid sedative effect or cause confusion to a victim. The most common drugs of this type detected are paracetamol and quinine, which is a natural component found in tonic water.

A further 28% of samples tested contained at least one controlled drug where the police force has not established if the drugs detected were knowingly used by or prescribed to the victim. Some of these will remain undetermined because the complainant has stopped engaging with policing or because the investigation has been closed as there is no additional evidence to identify an offender.

Figure 1- A breakdown of forensic result as of October 2023

Contains a controlled drug that supports a spiking incident: 64 (5%)

In these cases the police force shared the results with the victim who 64 confirmed that the drug detected was not knowingly used by them. The most common drugs detected were cocaine, ketamine, and MOMA.

Contain a controlled drug declared by the victim: 76 (6%)

The majority of drugs found in this sample set are illegal drugs associated with 76 the night-time economy such as ketamine, cocaine or MOMA but also includes some controlled prescription drugs.

Contain a medicinal drug: 98 (8%)

This can be a prescription or over the counter drug such as anti-histamines which can have sedative side effects.

Contain a drug of no concern or no drug at all: 651 (53%)

A drug of no concern is one that would not have a rapid sedative effect or cause confusion to a victim. The most common drugs of this type detected are paracetamol and quinine, which is a natural component found in tonic water.

Contained at least one controlled drug: 372 (28%)

In these cases the police force has not established if the drugs detected were knowingly used or prescribed to the victim. Some of these will remain undetermined because the complainant has stopped engaging with policing or because the investigation has been closed as there is no additional evidence to identify an offender.

Literature review

‘Date rape drugs’ – such as GHB, flunitrazepam (Rohypnol), and Ketamine - have historically been associated with spiking incidents. However, a review of the literature[footnote 18] found that these drugs were not found as often as might be expected in suspected spiking cases. In fact, in some studies they were found very rarely (e.g., no covert use Rohypnol found by Scott-Ham and Burton (2005), and ‘date rape drugs’ found in just 3 out of 152 cases of drug-facilitated sexual assault by Caballero et al., 2017). While delays in testing could explain why some drugs are not found in some cases (especially GHB which has a short detection window), many of the toxicology papers only include participants who presented for testing quickly after suspected ingestion and so it might be expected these drugs, if present, would be identified (though some authors do note false negatives are possible).

The University of Birmingham/NCA review highlights a consistently raised issue in the literature, namely that more attention should be paid to the risks from alcohol rather than drugs[footnote 19]This is understandable as alcohol (ethanol) was the most commonly found substance during testing and this can easily be used to spike drinks (e.g., putting an extra shot in someone’s drink or giving them an alcoholic drink instead of a non-alcoholic one).

What is a perpetrator’s motivation?

There continues to be limited data available on offenders and the reasons why they might perpetrate these crimes, particularly needle spiking. Data collated by the NPCC indicates that most spiking offences continue to have no secondary offence (meaning that spiking was used to facilitate another crime, such as theft, fraud, or Rape and Serious Sexual Offences (RASSO). In the year to October 2022, 16% of all spiking featured secondary offending. Where secondary offending does occur, it is significantly higher in drink spiking (63%) than other forms of spiking, and 88% of those are female victims. The NPCC is concerned that perpetrators may be taking advantage of interactions with victims (i.e., on dates) where there may already be alcohol involved, to extend their offending.

Breakdown of secondary offending type

| Assault/Violence | Fraud | RASSO | Theft/Robbery |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12% | 2% | 57% | 29% |

A summary of the key findings from the review[footnote 20] undertaken by Burrell et al (2023) - in relation to motivation - are as follows:

- Motivation to commit spiking was rarely stated explicitly but could potentially be inferred from the topics of the papers under review (e.g., if the paper was on drug-facilitated rape, it might be inferred that spiking in this context would be to commit a sexual offence).

- Some papers in the review listed offences that have been committed against victims of spiking. These included sexual assaults, robbery/theft, homicide, and/or kidnapping.

- Victims of spiking sometimes reported that a follow-on offence had occurred (such as rape or robbery) which could imply motivation. However, it is noted that follow-on offences did not always occur in spiking cases.

- Only two papers were identified which presented results on perpetrator reports of motivations for spiking[footnote 21].

- Swan et al. (2017) reported that 83 of their participants admitted they had perpetrated spiking (the total sample was 6,064). Of these, 51 provided reasons for their actions. These included to have fun, to have sex with/sexually assault someone, to calm someone down/make them sleep, to observe effects of drugs, and to be mean or exact revenge.

- McPherson (2007) reported that over 40% of motivations related to fun (as reported by participants who had committed drink spiking at least once). Other motivations included getting people drunk, and/or to facilitate sexual activity. A full list can be found in McPherson’s thesis (p.223-224)[footnote 22].

- As Swan et al. (2017) and McPherson (2007) are international papers – USA and Australia respectively – Burrell et al. (2023) conclude that additional research is needed to examine motivations for spiking in the UK context.

Barriers to prosecution

A key insight from our internal research is that challenges to prosecuting spiking cases do not result from insufficient laws but most likely occur at the investigative/evidence gathering stages.

As part of our review to determine the case for a specific criminal offence for spiking, we discovered that the police and CPS, in order to charge and prosecute a spiking incident (without a secondary offence), must have, at a minimum: an identified suspect, evidence of the substance used and its impact on the individual.

Assessing the impact of the offence on an individual can be simple to do through victim and witness testimony/statements. Identifying a suspect, (particularly when these incidents tend to occur in busy, night-time economy venues), testing the victim quickly and collecting any evidence that may have been used (drink receptacles, syringes and other paraphernalia) prove more challenging.

The primary issue is where the evidential gaps are. A key piece to review would be the forensics and identification of the suspect…We would only see a case where a suspect has been identified.

CPS

Suspect identified

- CCTV evidence of a suspect spiking the victim and whether by needle or drink

Challenges: CCTV coverage may not capture the suspect administering the drug at a visible angle; if not gathered quickly enough, CCTV may be overwritten by the venue

Or:

- Credible eyewitness(es) of a suspect spiking the victim

Challenges: Unless police are called to the venue at the time of the incident, It’s hard to identify eyewitnesses; the act of spiking is subtle and may not be seen by anyone

And:

Evidence of the drug and its impact

- Positive toxicology report (that can be used in court)

Challenges: samples need to be taken in a timely manner for tests to get an accurate reading; without an identified suspect, police are unlikely to pursue this line of action as it is expensive; victims need to confirm which substances they have willingly taken to identify those they haven’t

And:

- Evidence or the Impact of the drug on the Individual

Challenges: If the victim is late to reporting, it may be difficult to gather substantial evidence

In data published by the NPCC, only 12.5% (378) of reports were able to identify a suspect. Of those, only 4 (of 378 reports) resulted in a charge. However, it is important to note that these are of the cases being reported through the NPCC’s Operation Lester process. There may be other successful criminal justice outcomes received in spiking cases which have not been reported in through Operation Lester. Additionally, principal crime rules apply meaning that if an offence involved spiking, but also involved, for example, a sexual assault, the sexual assault crime is recorded and prosecuted and we cannot extract the data related to the spiking elements of that crime. That is why our interventions have been, and will continue to focus on improving awareness, enabling quicker testing, and promoting victim confidence, as well as identifying perpetrators and gathering evidence.

As already mentioned, there are societal and cultural reasons why spiking incidents may not be reported (and therefore cannot reach the charge or prosecution stages). During our internal research, the Home Office heard from victims and others who felt that without a secondary offence being committed, spiking was not serious enough to report on its own, or they felt unsure who to report to, or how.

No, I didn’t think to go to the police. I don’t know if it was because I wasn’t so confident […] But I also didn’t feel like I had a bad enough experience to bother the police. I felt like was really lucky.

Victim of spiking

[My friend who had been spiked] had been speaking to hotel staff so we didn’t know who we could trust there. We told the people at our apartments but didn’t really know who else to tell.

General Public

The voluntary consumption of drugs may also prevent a victim from coming forward to report. They might feel as though they will get into trouble for taking an illegal substance, or they may be concerned that the police will take them less seriously for doing so. The NPCC and CPS have issued guidance that makes clear that a victim should be considered a victim first and foremost, but it could still be a deterrent for reporting.

Support for victims

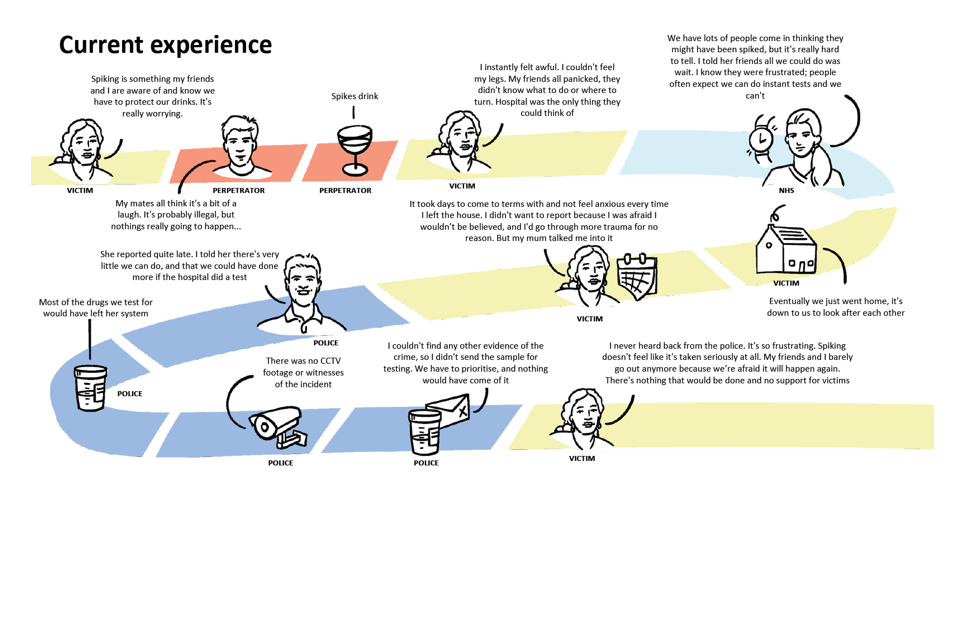

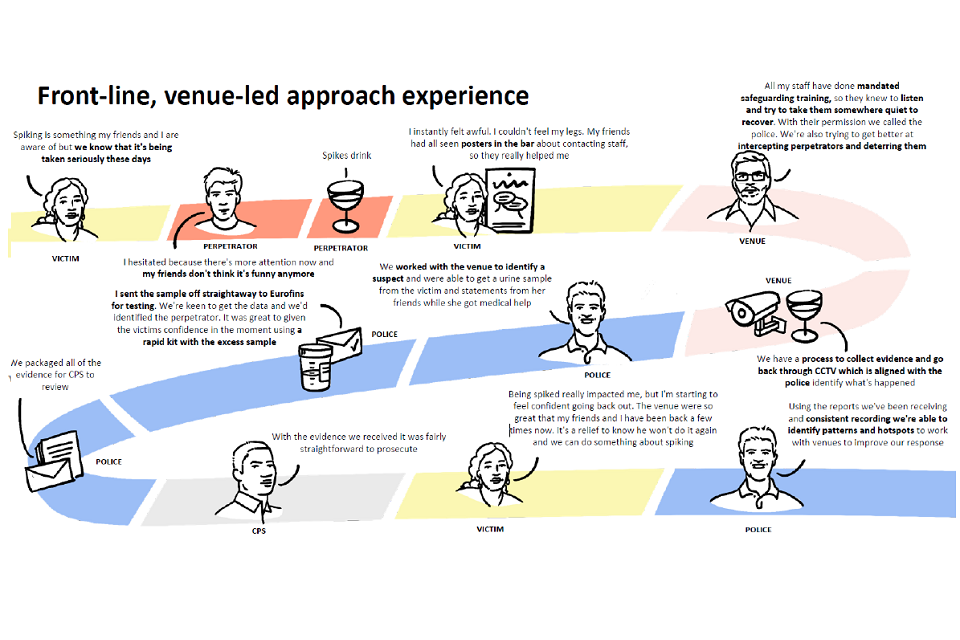

Figure 2 - “Current” Spiking Experience (as of Summer 2022)

Venues that operate in the night-time economy are areas of opportunity for safeguarding and prosecutorial support and so the early collection of evidence, identification of perpetrators and their ability to support customers is key. Where venues have training, proactive staff and communications and clear processes, they have been able to support victims, identify and hold perpetrators, and collect evidence to support investigations. Our spiking information and support pages aim to provide further information, guidance, and good practice for venues to draw upon and improve their safeguarding practice.

In one venue, 3 people came forward to say that someone was behaving suspiciously. The staff followed the process and alerted security who searched him. They used a testing kit to identify the person was trying to give out ketamine laced drinks. They called the police who were then able to act. The evidence was gathered in the night while the evening was still going on. The police were there within 15 minutes…” “Within the first four days of the campaign, we had our first arrest.” “People can see venues as the issue, but they’re part of the solution. People can be spiked in restaurants and pubs and house parties, where there aren’t security staff or our measures in place” “I have an open door to talk about it and can talk about it with venues to identify improvements even where someone doesn’t want to report.

Night-time Economy

If someone comes forward to say they think they’ve been spiked, the first step is to test the drink and then to wind back through the CCTV to see if they can identify someone.

Night-time Economy

if you’re spiked, you’re most likely to go to the bar, those people aren’t necessarily trained in the same way [as security staff]. That needs to be incentivised that those people are trained to deal with safeguarding situations.

Night-time Economy

It can sometimes be hard to tell if an individual is suffering from a health issue or has been the subject of a criminal act, including being spiked. We know that at times people can feel passed back and forth between the emergency services with a lack of clarity as to what the right approach is. The priority of those around the victim may simply be to ensure they are safe, and often reporting is not their first consideration.

I guess on the night if someone’s completely incapacitated you do everything you can to help them and notify the venue or the bar. Make sure they don’t end up somewhere they shouldn’t […] I’m not 100% sure really [where to go for support]

General Public

Assessment of the current law

With our criminal justice partners, we undertook a thorough review of the existing legislative framework to assess its fitness for the purposes of spiking.

Although some of the offences use archaic language and may not readily be identifiable as offences that ‘capture’ spiking behaviour, these existing offences can (and are) used to prosecute spiking crimes today, with some offences attracting maximum penalties of up to 10 years imprisonment. These include offences primarily focused on the harm caused, ranging from common assault and battery to grievous bodily harm (GBH), and their inchoate versions, for example attempting or conspiring to commit an offence. There are also offences that would cover spiking which are more prescriptive to how the harm is caused. These include sections 23 and 24 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 (“the 1861 Act”) and section 61 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (“the 2003 Act”).

Section 23 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861- Maliciously administering poison, so as to endanger life or inflict grievous bodily harm. “Whoever shall unlawfully and maliciously administer to or cause to be administered to or taken by any other person any poison or other destructive or noxious thing, so as thereby to endanger the life of such person, or so as thereby to inflict upon such person any grievous bodily harm, shall be guilty of felony, any being convicted thereof shall be liable”

Section 24 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 - Maliciously administering poison with intent to injure, aggrieve, or annoy any other person. “Whosoever shall unlawfully and maliciously administer to or cause to be administered to or taken by any other person any poison or other destructive or noxious thing, with intent to injure, aggrieve, or annoy such person, shall be guilty of a misdemeanour, and being convicted thereof shall be liable”

The offences in sections 23 and 24 of the 1861 Act contain identical definitions on the “conduct” element and only differ in relation to the “consequence” elements of the offences. The conduct element here is the unlawful and malicious administering or causing to be administered or taken “any poison or other destructive or noxious thing” and covers three differing circumstances:

-

administering a noxious thing to any person (substance is administered directly, i.e., injected);

-

causing a noxious thing to be administered to any other person (substance is administered by an innocent third party for example); or,

-

causing a noxious thing to be taken by any other person (for example, if a noxious substance is put in food, which is subsequently eaten).

Lord Bingham of Cornhill illustrated the three distinct offences in the case of Kennedy[footnote 23]:

Offence (1) is committed where D administers the noxious thing directly to V, as by injecting V with the noxious thing, holding a glass containing the noxious thing to V’s lips, or (as in R v Gillard (1988) 87 Cr App R 189) spraying the noxious thing in V’s face.

Offence (2) is typically committed where D does not directly administer the noxious thing to V but causes an innocent third party (TP) to administer it to V. If D, knowing a syringe to be filled with poison instructs TP to inject V, TP believing the syringe to contain a legitimate therapeutic substance, D would commit this offence.

Offence (3) covers the situation where the noxious thing is not administered to V but taken by him, provided D causes the noxious thing to be taken by V and V does not make a voluntary and informed decision to take it. If D puts a noxious thing in food which V is about to eat and V, ignorant of the presence of the noxious thing, eats it, D commits offence.

The section 23 offence has a required consequence; not only must the substance be administered, caused to be administered or taken, but it must also endanger the life of or inflict grievous bodily harm to the victim. The section 24 offence requires only the intent to “injure, aggrieve or annoy”; a much lower evidential threshold.

The maximum penalty for the section 23 offence is 10 years imprisonment, and 5 years imprisonment for section 24.

Section 61 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003: Administering a substance with intent

(1) A person commits an offence if he intentionally administers a substance to, or cause a substance to be taken by, another person (B) -

a. knowing that B does not consent, and

b. with the intention of stupefying or overpowering B, so as to enable any person to engage in a sexual activity that involves B.

(2) A person guilty of an offence under this section is liable-

a. on summary conviction, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months or a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum or both;

b. on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years.

Section 61 of the 2003 Act could apply where the victim is overpowered or stupefied by a person who administers a substance in order to make the victim sexually submissive. This offence may cover the use of so-called ‘date-rape’ drugs where it is administered without the victim’s knowledge or consent. It may also cover the use of any other substances that are intended to have the same effect. The maximum penalty for this offence is 10 years imprisonment.

By way of illustration, the section 61 offence has been found applicable to cases where the perpetrator spiked the victim’s drink and then went on to sexually assault them[footnote 24], or spiked the victim’s drink, intending to engage in sexual activity, but sexual activity did not occur[footnote 25]. This offence also applied in cases where social media had been used to lure victims to a model photoshoot, where they were then subsequently drugged, raped and/or sexually assaulted.[footnote 26]

We surveyed 29 Police forces, asking them specifically whether they had ever:

- identified a gap in the law/encountered spiking behaviour for which they were unable to identify an appropriate offence to record/charge

- encountered an incident which was recorded/charged using existing offences but where those offences were considered to be an inadequate fit for the behaviour in question

We found that none of the respondent forces reported any issues with identifying an appropriate offence, nor had they identified any spiking behaviour that wouldn’t be adequately covered by existing legislation.

Participants in our internal research project told us that there was already an assumption that spiking is illegal, even if they were not sure what specific offence covered it or what sentence was available. They were less certain, however, that spiking with additional alcohol was illegal.

Writing something down in the statute book isn’t going to stop someone doing something. Someone going around with a needle full of a drug looking to stab someone knows that isn’t allowed.

AGO

The problem of a specific offence – the more you put in, the more evidential burden you’ve got to prove it… The more obscure and specific you make it, the more difficult it is for the police to use it. They use the Offences against the Person Act because they know where it is, and they’re used to using it. If you’re not used to it, you don’t know it exists. You begin to lose that focus.

MoJ

Yes, it is definitely illegal. I would assume it is in the line of doing something with intent to harm… the intention of spiking is to violate them or do something against their will. So, I would assume it would be quite serious. I would assume someone is doing with the feeling that they’re never going to get caught.

Victim of Spiking

Festivals and events

The NPCC established a weekly process to prepare, monitor and review spiking at festivals and events during 2022. This ran for a 12-week period from 25th June 2022 using intelligence from National Police Coordination Centre Strategic Intelligence and Briefing [NPoCC SIB], but also information directly from force spiking leads and industry colleagues. Festival organisers and police command teams put in place a range of preventative and investigative measures to respond to spiking and although incidents of both drink and needle spiking were reported, the levels were not as high as anticipated. For this period:

-

Total number of all reported spiking offences for this period – 1324

-

Number of spiking offences at festivals/events – 96 – 7% of the total

- 65% of offences were needle spiking, 31% drink spiking, remainder other/unknown.

-

Where details were provided 73% victims were Female and 26% victims were Male

-

Average age of victim was 21 years old, with age ranging from 14 to 61.

- There was only one offence with a recorded secondary offence (RASSO)

Students and universities

A peak in spiking incidents reported to police, occurred between October – December 2021.This coincided with the start of the Autumn university term and ‘freshers’ week’. Similarly, in data collected by NPCC, ‘student’ was the highest recorded occupation (13.5%) in October 2022 which is an increase from both August (2%) and September (7.5%) figures.[footnote 27]

This increase in reporting in Autumn 2021 led to concerns that spiking offences would surge again around Fresher’s week in 2022. Data collected by the NPCC does not indicate that this happened. Although NPCC did see an increase in reporting (for all forms of spiking) in October 2022 it was not at the levels seen in 2021.

Conclusions and findings

The legislation

A range of offences currently exists to prosecute incidents of spiking and the police are confident that, where they have the evidence to charge an offender with this crime, the law supports that. However we have heard from stakeholders that the offences used to prosecute cases involving spiking, are not necessarily seen nor understood to be ‘spiking’ offences and therefore the language used in those offences prevents victims from reporting such incidents. Additionally, the police have said that when they do get a spiking report the ability to identify perpetrators and swiftly collect toxicology samples and other evidence remains the most significant barrier to a successful outcome. We understand that while spiking is already covered by existing statute, many of these address spiking incidentally, not by design. We therefore intend to bring forward a legislative amendment in the Criminal Justice Bill to modernise the language of the current offence(s) which may help increase public awareness of the illegality of spiking and encourage the reporting of such incidents. We will also need to ensure that any action we take to modernise the language of the current offences, is done alongside the introduction of measures which improve upon identification and evidence collection to secure better outcomes for victims.

Specificity and data

Introducing a new offence for the sake of specificity would overlap with existing offences, which would add unnecessary complexity not only within our statute books but for prosecutors in terms of what offence they should apply to any given case.

Additionally, introducing new offences to improve crime reporting and data analysis could potentially confuse the data analysis picture further because a new offence would add to the existing offences that a spiking incident could be recorded under, rather than replace those offences.

It is for these reasons that modernising the language of the current offence(s), rather than introducing something new to an already vast statute book, could be a better way to address the concerns that have been raised.

Scale, nature and prevalence

As with other crime types which disproportionately affect women and girls, underreporting remains a significant barrier to improving our understanding.

However, from the data we do have available, we believe that the initial peak of needle spiking incidents that occurred in Autumn 2021 has passed, though drink spiking has remained at consistent levels throughout the period. Drink spiking incidents are linked to the largest proportion of secondary offending (compared to incidents utilising needles/food/vapes).

Young women are particularly vulnerable, and busy and crowded venues/events, such as bars and clubs, are likely to put them at a greater risk of needle spiking.

We do not know enough about why perpetrators spike, but we do know that in cases of needle spiking, a secondary offence does not always occur. This may suggest that perpetrators think it is ‘fun’ or ‘get off’ on raising the alarm and consider it easy to do without fear of being detected.

Results from the Police’s rapid urine screening capability shows that in those cases where a urine sample has been taken, 5% of those suggest that spiking has occurred – though the drugs being used tend to be those more associated with the night-time economy, rather than traditional ‘date-rape’ drugs. The majority (53%) of samples tested contained a drug of no concern or no drug at all. However, these tests cannot identify whether someone has been spiked with additional alcohol, and if a victim does not feel confident to report straight away it could be that the drugs used, have left their system at the point they are tested.

Chapter 2: Tackling spiking

In Chapter 1 we discussed the work Government and other partners have been doing to better understand the scale and nature of spiking in order that we can best address it. We believe that in order to provide the best support for victims and the greatest opportunity to identify and prosecute offenders, there needs to be a whole-system approach.

Why do we need to tackle spiking?

This is an invasive, upsetting and dangerous crime. Perpetrated covertly and, as we have seen, sometimes because it’s viewed as ‘funny’ or ‘a joke’. This is not funny, and we must ensure that message is clear. A person has an absolute right to be in public spaces without the risk of being spiked.

We know that there are often societal pressures that may prevent an individual reporting this crime, including mistrust in the police, thinking that the police won’t be able to do anything or, in the case of some victims, a sense of shame.

We are clear that anybody who reports that they have been spiked will be taken seriously – this chapter will set out the range of activities that have been carried out to improve the reporting experience and subsequent care of victims, alongside the issues faced in terms of bringing spiking cases to trial.

What has the government done so far?

The government’s priority has been, and continues to be, to support victims and bring perpetrators to justice.

Supporting victims

Practical efforts

We have made a £30 million investment to date for projects with a particular focus on protecting women in their communities through Round Three of the Safer Streets Fund and the Safety of Women at Night Fund. We have invested £50 million for 111 projects, and allocated an additional £42 million for 121 projects, through Rounds Four and Five of the Safer Streets Fund, respectively, which have a focus on tackling violence against women and girls in public places, as well as neighbourhood crime and anti-social behaviour.

This funding has supported a range of interventions which seek to tackle violence against women and girls, including bystander training programmes, taxi marshals and educational awareness-raising initiatives. Through the Safety of Women at Night Fund and fourth round of the Safer Streets Fund we have awarded funding for a range of initiatives to tackle drink spiking directly, including:

-

Acquisition of drug testing machines

-

Provision of training and accreditation schemes for businesses and in the NTE, as well as outreach programmes for youth, and bystander training

-

Support for awareness-raising activity and communications campaigns (such as the “Good Night Out” campaign and “Ask for Angela”)

-

Installation of additional CCTV and streetlighting

-

Physical barriers to drink spiking including “StopTopps” and “bottle spikes” (which narrow the neck of bottles to reduce the risk of spiking)

-

Personal safety alarms/apps

-

Support for organisations like the Street Pastors

Festivals and events

The Home Office worked closely with the Festivals and Outdoor Events sector in 2022 and 2023 to ensure the safety of the public at summer events.

For the 2022 season, the NPCC developed practical solutions including joint letters with partners, and comms campaigns at specific festivals, including those targeting would-be offenders. Local policing teams were briefed on how to respond to a spiking incident and clarity was provided to ensure that investigating the spiking incident was prioritised over pursuing a victim for taking illegal drugs.

The sector undertook a number of actions in preparation:

-

Multiple festivals committed to have pre-show comms programmed on their social media channels regarding spiking and awareness, with awareness posters visible at each bar on site.

-

Training packages for bar and event staff.

-

All festivals had medical and welfare teams onsite, with exact provisions and plans provided for in their individual Event Management Plans (EMPs) and in discussion with Safety Advisory Groups (SAGs) and relevant agencies at local level.

The Association of Independent Festival’s (AIF) “Safer Spaces initiative” launched a charter of best practice in 2017 with subsequent updates in 2022 and 2023. More than 90 Festivals signed up. The charter sets out the sector’s commitment to tackling violence against women and girls at their events and sits alongside other campaigns such as Stamp Out Spiking and Ask for Angela. Post 2022 season, the sector surveyed their 92 members. Some key findings shared with us include:

- 87.5% had a specific policy to address sexual assault and harassment onsite

-

92% had a disclosure/reporting process for onsite sexual assault/harassment. The majority of these included a phone number/email address to report to onsite or post-event and provided connection to their nearest SARC.

-

Many events had additional support teams onsite alongside their standard welfare provision, including UN Women, Safer Spaces Now, Safe Gigs for Women, trained safe-guarders.

-

77% implemented Ask for Angela onsite.

-

45% had participated in, or members of their team had participated in, specialist training from organisations such as Rape Crisis or Good Night Out.

- Many events also implemented other measures, (including physical measures like drink toppers) to help prevent spiking.

Students and universities

Because of the particular vulnerability in the student population, in May 2022 Home Office and Department for Education Ministers co-chaired a roundtable for education sector leaders to aid policy development and share effective practice. The event focused on prevention, reporting and victim support. This led to the formation of a working group chaired by Professor Lisa Roberts, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Exeter. The working group was charged with examining how best to drive spiking incidents out of University towns and cities. The group comprises of university vice-chancellors, Universities UK (UUK), police, campaigners, students, and victims. This forms part of the wider Government mission to tackle violent and sexual crimes and strengthen victims’ rights.

The group collaborated on the development of guidance[footnote 28] for the sector – a ‘Practice Note’ published by UUK in August 2022, in preparation for the start of the Autumn 2022 term and Freshers’ Week. This was complemented by an NPCC communications campaign targeted at students highlighting the importance of reporting and testing. The level of reported spiking in these settings over this period was significantly lower than the previous year.

The recommendations within the practice note included:

-

Universities’ plans should recognise the complexity of spiking – for example anyone can be a victim of spiking, and it is not always connected to sexual assault. It can be via needles or drink spiking, and may not always involve illegal drugs;

-

Ensuring university communications place the problem with perpetrators, not victims, avoiding communication campaigns that may be viewed as ‘victim blaming’;

-

Disciplinary processes for perpetrators must be clear and well-explained;

-

Universities should have clear internal reporting and support systems;

-

Universities should work in partnership with student unions, police, night-time venues, and other partners.

It’s vital that all students feel safe at university and can enjoy their student experience without fear of being harmed. It is important that universities take spiking seriously, and work alongside their local partners and authorities to ensure that we reduce the risk of spiking and raise awareness of the support available, so victims of spiking can come forward for support in confidence.

Professor Lisa Roberts, Vice Chancellor of the University of Exeter, and Chair of Department for Education’s Spiking Working Group

The practice note has been positively received by the sector and has been used by universities to inform and improve their response to spiking. In January 2023, UUK published an update to the practice note, including further good practice and resources for universities. [footnote 29]

Case study

Middlesex University created a spiking campaign film, ‘What happened to you last night?,’ which was produced by Middlesex film students. The film was produced to support the launch of UUK’s practice note on helping universities to prevent and respond to spiking. The University has also produced an information sheet about spiking and information about how to report spiking through its ‘report it to stop it tool’ which has the capacity for anonymous reporting. The resources were used as part of an awareness campaign during induction and will be used throughout the academic year.

‘Report it to stop it’ Middlesex University

Universities UK’s annual conference in March 2023 included a follow-up presentation “Supporting student safety in the night-time economy and public spaces”, chaired by Professor Lisa Roberts and involving members of the spiking working group.

Health first

Spiking can affect victims’ physical and mental health and emotional wellbeing. The initial effect on a victim’s physical health can mean that some victims present to health care providers such as A&E. The primary responsibility for an emergency department is to address the medical needs of the victim, rather than collect forensic samples. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine, in conjunction with the NPCC, published a position statement for emergency departments on the treatment of victims of spiking in July 2022.[footnote 30] The document clarifies the distinct roles of emergency departments and the police in responding to spiking. As well as addressing the patient’s medical needs, the statement advises that emergency departments encourage victims to contact the police and, where the victim gives consent, help facilitate this. It also encourages emergency departments to implement local measures to enable anonymous data sharing with local crime prevention partnerships (as with other forms of assault) of any reported incidents of spiking.

In addition, the NHS website, and the FRANK website[footnote 31] provided updated information and advice for the public on spiking.

UKHSA issued a briefing note to health protection teams on responding to spiking enquiries and NHS England also issued the following messages to their Emergency Preparedness, Resilience and Response communications team:

-

If an individual has been spiked and sexual assault has not happened / is not suspected, then they should seek urgent medical advice at an emergency department.

-

If sexual assault or abuse has happened / is suspected and they are in a conscious state, then they should go to a Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC), where tests can be undertaken, including bloods.

ENOUGH.

Spiking has been incorporated into the Government’s “Enough” campaign to tackle violence against women and girls.

-

This includes spiking being listed and defined as a VAWG harm on the campaign website, and victims being able to filter support services available for victims of spiking. As of March 2023, as part of Phase 2 of “Enough”, a suite of spiking-specific assets were developed and circulated for use in venues and as part of an organisation’s own efforts to tackle spiking.[footnote 32]

-

In September 2022, the National Police Chiefs Council produced a direct communications campaign designed to communicate to students what to do if they had been spiked. Universities were also encouraged to promote ‘Enough’ campaign materials aimed at tackling violence against women and girls ahead of the Autumn 2022 term.

-

Campaign materials have also been shared with the wider education sector via the Department for Education, and further supported by the Russell Group.

Pursuing perpetrators

Evidence gathering

The Police have worked with the forensic provider Eurofins to develop a rapid testing capability which enables law enforcement to better support victims and pursue perpetrators and has assisted in building our understanding of what drugs are being used and how common or not they are. The Home Office has provided an additional £70,000 in funding to law enforcement to support additional testing efforts. This funding enables police forces to examine an additional 200 urine samples from suspected victims and provide a greater understanding of the range of substances being used in spiking incidents.

Partners, such as those working with the night-time economy and licensing partners have issued guidance and best practice to venues on how to secure evidence following an incident.

We have worked with NCA and academics from the University of Birmingham to better understand the motivation of perpetrators so that we can target a response accordingly.

Zero tolerance to drug possession

In April 2022, the Government reclassified Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid (GHB) and the related substances Gamma-Butyrolactone (GBL) and 1,4-Butanediol (1,4-BD), from Class C to B under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. These are so-called “date rape” drugs, which have been used in drug-facilitated crime (though as we have discussed there is little evidence to link these drugs to needle-spiking specifically). This followed expert advice from the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), which conducted a review of the harms of these substances.

The move to Class B will increase the maximum penalty for unlawful possession from two years’ imprisonment, or a fine, or both, to five years’ imprisonment, or a fine, or both. This will signal to the public that offences involving these substances are treated seriously and subject to appropriate penalties, acting as a deterrent for their possession and supply.

Targeted communications

The Police Crime Prevention Initiative (PCPI) is a police-owned organisation that works on behalf of police forces throughout the UK to deliver a wide range of crime prevention and police demand reduction initiatives. In 2022, its Licensing Security and Vulnerability Initiative – Licensing SAVI – in conjunction with NPCC, developed a range of communication products and guidance[footnote 33] for use by owners and operators of licensed premises to provide a safe and secure environment for their managers, staff, customers, and local communities.

Review of the current law

We undertook a full and thorough assessment of the legislative framework and concluded that existing law covers a broad range of behaviours and incidents that include and extend beyond spiking, with tough penalties attributed to them. However, we do recognise that there is not a single defined offence, nor were the existing laws drafted with the offence of what we currently define as spiking (i.e., through drinks and needles) in mind. Given the modern realities of the offence we think there is a case for a legislative change and hope this will encourage victims to come forward.

System wide response

Security Industry Authority

The Security Industry Authority (SIA) has ensured that the training which door supervisors and security guards must undergo in order to obtain an SIA licence includes specific content on preventing violence against women and girls, and it is running campaigns to remind the industry and operatives of their role and responsibility in keeping people safe, with a focus on women’s safety.

To ensure private security operatives are sufficiently equipped to protect the public, the mandatory training requirements include topics such as identifying factors that make someone vulnerable and identifying the actions they should take to help vulnerable individuals. It identifies behaviours that may be exhibited by sexual predators such as close monitoring of people who may be in vulnerable situations, buying them drinks or gifts, and suspicious behaviour around certain times and venues. The inappropriate use of technology e.g. upskirting with phones is also referenced. Mandatory training also covers awareness of the use of drugs in facilitating sexual assaults, with particular reference to GHB or drugs commonly known as ‘date rape’ drugs and will include specific training on spiking.

Licence holders’ training includes understanding when it is appropriate to step in to call a friend for assistance, to call for a licensed taxi, or to seek help from other professionals or services better placed to help. They are taught how to deal with allegations of sexual assault, namely by following the organisation’s policies and procedures, notifying the police, and recording and documenting all available information. Door supervisors are required to achieve a First Aid certificate and understand the appropriate First Aid response to a potential spiking incident.

The Safer Business Network, supported by the SIA, are delivering an e-learning package of Welfare and Vulnerability (WAVE) training for security business, which includes a module on spiking.

The Night-Time Industries’ Association (NTIA)

In 2022, the NTIA developed guidance and good practice[footnote 34] for its membership. It includes practical information on what to do if someone has been spiked, training and education tools for staff and volunteers, and a checklist for venues in keeping people safe.

The Local Government Association (LGA)

In response to the increase in reports of spiking, the LGA developed a short guidance note[footnote 35] for councils which provides a brief overview of spiking, suggests some preventative actions licensed premises and licensing authorities can take, highlights best practice case studies, and shares a checklist that the LGA encourages licensing authorities to consider. Examples of good practice can be found via our spiking information and support pages.

They also issued a joint press release[footnote 36] with the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners (APCC) to raise awareness of spiking (specifically spiking by adding extra alcohol to a person’s drink without telling them) as students headed to university for freshers’ week.

Chapter 3: What further action will Government and others take to continue to tackle this issue?

As set out under Chapters 1 and 2, we have taken significant steps to develop our understanding of and take action to tackle spiking. It is our hope that the action taken to date provides long-lasting results in stamping out this abhorrent crime and provide the best possible support to potential and suspected victims.

Although we are not seeing the levels of spiking reported in Autumn 2021, we are determined to do what is necessary to tackle this crime. There are continued gaps in our understanding around motivations of perpetrators. The ability to identify and bring perpetrators to justice is also an area that needs focus, requiring a holistic response across police, business, and others. That is why we believe that ongoing commitment from our partners and long-lasting solutions are key.

Enhancing our understanding

Prevalence, scale and nature

Whilst it’s encouraging that we are not seeing the levels of needle spiking we did in Autumn 2021, drink spiking continues to be a problem that we must address. We need to continue to build our understanding of this crime. That is why:

-

The Home Office and the Office for National Statistics will consider the value of adding a question into the Crime Survey for England and Wales to better assess the public’s experiences of spiking in order to provide a more robust prevalence estimate.

-

The Home Office is working closely with police forces to ensure that a consistent approach is taken in relation to recording crimes where victims make reports. This includes developing methods for better identifying the use of drugs, alcohol and needles and will also lead to better understanding where other crimes, in addition to the spiking crime, have been committed.

-

The NPCC, NCA and others will consider further academic research to strengthen our understanding of perpetrator motivations.

Research into the capability of existing test kits with potential development for a rapid spiking test kit

We understand the need for venues and members of the public to feel assured in the moment and that they want to have the capability to immediately test their drinks if they suspect they may have been spiked. Some areas, like Bristol, have even received funding from the Home Office to carry out activity to tackle spiking, including the use of self-testing kits.

We recognise that these kits can provide a quick result, but we also need to be clear that there is no formal benchmarking/accreditation process and therefore the results may not be consistently accurate. It remains the Government’s position that currently, the only reliable method of testing a spiking sample is through the Eurofins rapid testing capability.

That said, we will be giving up to £150,000 to the Police’s Forensic Capability Network (FCN) to begin research into the capability of existing rapid drug-testing kits.

This project will look at existing rapid testing kits to assess their accuracy and efficacy, with a view to identifying if any currently available kit meets the police requirement or conclude that either a new product is needed or that the existing process of using a Forensic Service Provider remains the best option.

Supporting victims

Our work over the past 18 months has revealed that much of our efforts need to be focussed on putting victims first by giving them the confidence to report and ensuring their safety in public spaces.

Modernising the language of offences on our statute book

We have not identified any gaps in the law that a new, bespoke, offence would fill.

However, we have listened to some views expressed by victims and stakeholders and recognise that better reflection of modern terminology within the existing legislation may help deter offenders and encourage more people to come forward to report incidents of spiking.

We intend, therefore, to bring forward a legislative amendment in the Criminal Justice Bill to modernise the language of the current offence(s) which may help increase public awareness of the illegality of spiking and encourage the reporting of such incidents.

Online reporting tool and spiking advice

-

Since 12 April, a small number of police forces have been piloting a new online reporting tool for spiking, alongside a wide range of supporting advice pages. This has been developed as part of the NPCC’s wider action to tackle Violence Against Women and Girls.

-

There are a number of specific advice and information pages, which cover a broad range of spiking advice, ranging from “What to do first if someone has spiked you” and “spiking myths” to pages on “What happens during a spiking investigation” and “What happens if a spiking case goes to trial.”

-

The reporting tool allows individuals to report incidents of spiking anonymously or not and has been tested with a user group of individuals who had been spiked in the past.

-

Initial feedback on the service with the user group indicated that they felt they were being listened to, given the right information, and acknowledged this sort of information would have been useful when they were spiked in the past.

The tool is currently being rolled out to all force areas and the Home Office will work with policing to scope this work aiming to begin development of a national reporting method as part of the police’s Single Online Home platform’s 24/25 roadmap. This piece of work builds on previous communication campaigns stressing the importance of reporting and testing so that policing can understand the true nature of spiking and tailor its response accordingly.