MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine: advice for pregnant women

Updated 20 January 2025

Introduction

Immunisation with rubella, measles-rubella (MR) or MMR vaccine whilst pregnant or shortly before becoming pregnant has no known risk. MMR vaccine is not recommended in pregnancy as matter of caution.

Vaccine in pregnancy surveillance was established in 1981 specifically for rubella vaccine, originally under the National Congenital Rubella Surveillance Programme. Rubella vaccine has since been replaced with combined MMR vaccine. The Surveillance Programme was set up to address theoretical concerns from vaccinating pregnant women with live rubella vaccine virus. This was because of the known risk of congenital rubella syndrome after natural rubella infection (German measles) in early pregnancy. Information from surveillance of these cases in the UK has helped provide additional assurance of the lack of a specific risk from the rubella vaccine virus in pregnancy.

The safety of rubella-containing vaccines in pregnancy

In the USA, UK and Germany, hundreds of women have been followed through active surveillance since the 1970s. This includes 293 who were vaccinated with rubella-containing vaccine within 6 weeks of their last menstrual period. None of the babies had permanent abnormalities compatible with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) (1). A small number of babies (around 16) had evidence that they had been exposed to the weakened vaccine virus (from blood tests) but there was no sign that the vaccine had affected the development of the infant.

Very large measles-rubella vaccination campaigns, run between 2001 and 2008, have targeted women of child-bearing age in South America and Iran (2, 3, 4, 5, 6). Comprehensive, prospective surveillance of pregnant women during these campaigns has provided further substantial evidence of the safety of measles and rubella containing vaccines in pregnancy. During these campaigns over 30,000 pregnant women inadvertently received MR vaccine. The vaccine had been given either during pregnancy (the majority were less than 12 weeks pregnant) or up to 30 days before these women had conceived.

In the above studies about 3,000 women were susceptible to rubella, meaning they were not already immune and so at potential risk of the virus passing to the baby. Extensive follow-up of the outcome of these pregnancies was very reassuring. Whilst a very small number of babies were shown to have been exposed to the weakened vaccine virus in the womb, no babies developed congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). There was also no increase in the risk of miscarriage or stillbirth in pregnant women who were susceptible (non-immune) when they were vaccinated when compared to those protected by prior immunity (7).

These large-scale vaccination programmes were carried out at a time when natural rubella infection was high in those countries and so it is was very unlikely that an infant with the clinical features of CRS would be missed (2). During 2001 to 2002, 56 infants with CRS were reported to the San Paulo State Health Department. None of these were born to mothers vaccinated in pregnancy and so it was concluded that all were due to natural infection (7).

Pregnant women who have received MMR vaccine

Therefore, there are no safety concerns, either for the mother or the baby, when rubella-containing vaccine is given in pregnancy or shortly prior to pregnancy. Women who have been immunised with MMR or single rubella vaccine in pregnancy can be immediately reassured. Such an incident would not be a reason to recommend termination of pregnancy (8).

The UK Vaccine in Pregnancy Surveillance Programme

All exposures to MMR vaccine from 30 days before conception to any time in pregnancy should be reported to the UK Vaccine in Pregnancy Surveillance programme. This is run by the Immunisation Department of UK Health Security Agency. The objectives of the UK Vaccine in Pregnancy Surveillance are to compile additional information on women who are immunised with specified vaccines whilst pregnant to monitor the safety of such exposures. These data will be used to better inform pregnant women who are inadvertently immunised, their families and health professionals who are responsible for their care.

Natural rubella infection in pregnancy and congenital rubella syndrome

Natural rubella infection in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy if a woman is not immune also puts the baby at risk from the infection. Rubella infection in the baby during the first 16 weeks of pregnancy is associated with a high risk of major and varied congenital abnormalities, commonly known as congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). If rubella infection occurs between 16 and 20 weeks of pregnancy in a woman who is not already immune, the child may be deaf but is unlikely to have other features of CRS.

In contrast, rubella containing vaccine contains a weakened strain of the rubella virus and there is no known risk associated with giving rubella or MMR vaccine whilst pregnant or shortly before becoming pregnant. Rubella infection prior to the date of conception, or after 20 weeks of pregnancy, carries no documented risk to the baby.

Reducing congenital rubella syndrome by immunisation

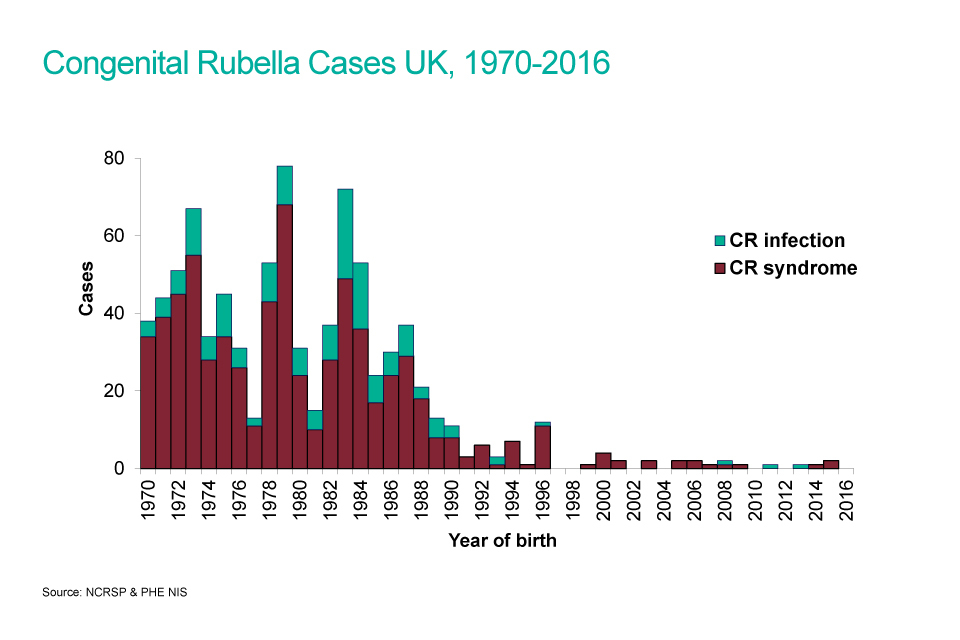

In 1970 a schoolgirl rubella immunisation programme was introduced in the UK. This selective policy was effective in reducing the number of children born with CRS (see graph) but rubella continued to circulate and any remaining non-immune women were often exposed via their own or other young children. Measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine was introduced in 1988 for all children in the second year of life, with the aim of interrupting circulating rubella.

In 1994, a national measles and rubella vaccine campaign targeted all school aged children (5 to 16 years) in 1994 and the schoolgirl vaccination programme was discontinued. A routine second MMR immunisation at 4 years of age was subsequently introduced in 1996.

Before rubella vaccine became available, an estimated 200 to 300 babies were born each year with CRS in the UK. In the 10 years between 2005 and 2014 there have been 7 cases of CRS born in the UK.

A bar chart showing congenital rubella cases from 1970 to 2016.

References

- Best JM, Cooray S, Banatvala JE. Rubella. In: Mahy BMJ and ter Meulen V (editors) Topley and Wilson’s Virology, 10th edition. London (2004): Hodder Arnold

- Castillo-Solorzano C, Reef SE, Morice A and others. ‘Rubella Vaccination of unknowingly pregnant women during mass campaigns for rubella and congenital rubella syndrome elimination, The Americas 2001 to 2008’ Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011: volume 204, pages S713 to S717

- Da Silva e Sa GR, Camacho LAB, Stavola MS and others. ‘Pregnancy outcomes following rubella vaccination: a prospective study in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2001 to 2002’ Journal of Infectious Disease 2011: volume 204, pages S722 to S728

- Soares RC, Siqueria MM, Toscano CM and others. ‘Follow-up study of unknowingly pregnant women vaccinated against rubella in Brazil, 2001 to 2002’ Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011: volume 204, pages S729 to S736

- Hamkar R, Jalilvand S, Abdolbaghi MH and others. ‘Inadvertent rubella vaccination of pregnant women: evaluation of possible transplacental infection with rubella vaccine’ Vaccine 2006: volume 24, pages 3,558 to 3,563

- Namaei MH, Ziaee M and Naseh N. ‘Congenital rubella syndrome in infants of women vaccinated during or just before pregnancy with measles-rubella vaccine’ Indian Journal of Medical Research 2008: volume 127, pages 551 to 554

- Sato HK, Sanajotta AT, Moraes JC and others. ‘Rubella vaccination of unknowingly pregnant women: the Sao Paulo Experience, 2001’ Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011: volume 204, pages S737 to S744

- Tookey PA, Jones G, Miller BH, Peckham CS. ‘Rubella vaccination in pregnancy. Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre Review 1991: volume 1, issue 8, pages R86 to R88