Country policy and information note: ethnic and religious groups, Vietnam, December 2024 (accessible version)

Updated 22 September 2025

Version 4.0, December 2024

Executive summary

Vietnam has an estimated population of 105 million and the government recognises 54 ethnic groups. The majority of the population, 85%, belong to the Kinh ethnic group with the remaining belonging to one of recognised others. There are approximately 26.5 million religious adherents.

The law recognises the rights of members of ethnic groups and the constitution states that people have the freedom to follow any religion.

Some members of ethnic minority groups also belong to a religious minority.

People are unlikely to face persecution or serious harm from the state on the basis of their ethnicity alone. However, where the government believes members of an ethnic group have separatist aims or are advocating for human rights, such as some members of Montagnard ethnic group, then they are likely to face persecution or serious harm.

Religious groups in Vietnam are divided into those that are registered with the Government Committee for Religious Affairs (GCRA) and unregistered groups.

In general, there is no real risk of state persecution or serious harm on account of a person’s religious beliefs for persons belonging to government registered groups.

People are unlikely to face persecution or serious harm from the state on the basis of their membership of an unregistered group alone. Members of unregistered religious groups who also belong to an ethnic minority, who promote religious freedom or are involved in activities which are perceived by the government to advocate separatism, and who come to the attention of the authorities are likely to face persecution or serious harm.

A person who has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state is unlikely to obtain protection or be able to internally relocate.

Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

All cases must be considered on their individual facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate they face persecution or serious harm.

Assessment

Section updated: 16 December 2024

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

-

a person faces a real risk of persecution/serious harm by the state because they are a member of an ethnic and/or religious minority group.

-

the state (or quasi state bodies) can provide effective protection

-

internal relocation is possible to avoid persecution/serious harm

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely to be certified as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 Decision makers must also consider making an international biometric data-sharing check, when such a check has not already been undertaken (see Biometric data-sharing process (Migration 5 biometric data-sharing process)).

1.1.4 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 Actual or imputed race and/or religion. Some cases may also involve actual or perceived political opinion and where this is the case decision makers should additionally refer to the Country Policy and Information Note on Vietnam: Opposition to state.

2.1.2 Establishing a convention reason is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of an actual or imputed Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.3 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds, see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1 Ethnic groups

3.1.1 This note provides an assessment on the situation for ethnic minorities and although sources often refer to them collectively, the experiences of each group may differ. Where information is available, the note will refer to and consider the treatment of each specific ethnic group discretely (see assessment of risk in sections 3.2-3.5 below)

3.1.2 Within the estimated population of 105 million the government recognises 54 ethnic groups. Around 85% belong to the Kinh (Viet) ethnic group. The remaining 15% (approximately 14.1 million people) belong to one of the other 53 minority ethnic groups. 86% of ethnic minority groups live in the mountainous and highland regions of Vietnam (see Demography and geography).

3.1.3 All recognised ethnic minorities are Vietnamese citizens, and the law recognises the rights of ethnic minorities to use their languages and protect and nurture their traditions and cultures. However, whilst the government voted in favour of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), it does not recognise ethnic minorities within Vietnam as Indigenous Peoples meaning they are unable to have the right to autonomy or self-govern but this is well short of constituting persecution/serious harm (see Legal status of ethnic groups).

3.1.4 Although the law prohibits discrimination against ethnic minority groups, they remain disproportionately the poorest citizens, with 90% of the country’s extreme poor belonging to an ethnic minority. However, the government has introduced a National Target Program for sustainable poverty reduction for 2021-2025 and as of August 2024, poverty rates among ethnic minority households have decreased by more than 3% per year during the program (see Poverty and access to services).

3.1.5 Ethnic minority groups benefit from some government concessions, such as exemptions from school fees however, they generally have less access to services compared to the Kinh majority. Lack of documentation can also affect access to public services such as education and healthcare. Some ethnic minorities lack documentation due to legal loopholes, denial of passport applications at a local level or failure of parents to register children at birth (see Legal status of ethnic groups, Government policies, Poverty and access to services and Documentation).

3.1.6 Where a person is a member or perceived to be a member of a group who the government believes to have separatist aims or has been involved in advocating for land rights, decision makers should also refer to the Country Policy and Information Note on Vietnam: Opposition to state.

3.1.7 If the person is a member of a religious group, then reference should be also made to the relevant assessment of risk in sections 4.2 and 4.3 below.

3.1.8 Each case will need to be considered on its facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate that they are at risk of persecution.

3.2 Chinese (Hoa/Han)

3.2.1 Members of the ethnic Chinese (Hoa/Han) group are unlikely to face persecution or serious harm from the state on the basis of their ethnicity alone. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.2.2 Government statistics from 2019 recorded 749,466 people belonging to the Hoa ethnic group, most of the population reside in urban areas in the south of Vietnam (see Ethnic groups - Chinese (Hoa or Han)).

3.2.3 Most people from this group do not belong to a particular religious group. Where they do have a faith, it is most likely to be an ethnic/folk religion or Buddhism (see Ethnic groups - Chinese (Hoa or Han)).

3.2.4 Poverty among ethnic Chinese has decreased more than any other ethnic group and they are well assimilated into Vietnamese society, particularly due to their importance to the Vietnamese economy. In the sources consulted no information could be found detailing specific adverse treatment against Hoa or Han people due to their ethnicity (see State treatment of specific ethnic groups - Chinese (Hoa or Han)).

3.3 Montagnards (or Degar)

3.3.1 Members of the Montagnard ethnic group are likely to face persecution or serious harm from the state, particularly where they are politically active, or perceived to be politically active and/or are Christian.

3.3.2 The Montagnards are a group of more than 30 indigenous communities who traditionally inhabit the Central Highlands. There are between one to 2 million Montagnards in Vietnam (see Ethnic groups - Montagnards (or Degar))).

3.3.3 The majority of Montagnards that follow a religion are Protestant, although there are small communities of Montagnards who Catholic and a small number belong to other religions such as Adventism or Brahmanism. Many Montagnards worship in unregistered house churches and they have been subject to surveillance, discrimination and pressure to join state-approved religious groups (see Ethnic groups - Montagnards (or Degar)) and State treatment of specific religious groups - Protestants).

3.3.4 The Montagnards fought alongside the American and South Vietnamese troops during the Vietnam war (1955-75) and are now still treated with suspicion by the Vietnamese authorities as they are unsure of their loyalty to the communist regime (see Ethnic groups - Montagnards (or Degar))).

3.3.5 In June 2023 armed attacks in the Dak Lak province resulted in the death of 9 people, including 4 police and 2 local officials. The Ministry of Public Security claimed that Montagnard groups were behind the attacks and whilst the motive for the attacks was unclear, one government official acknowledged that the growing wealth gap and poor land management by local officials may have been contributing factors. In early 2024, 100 people were convicted during a mass trial for their involvement in the attacks with most people belonging to the Montagnard ethnic group. All defendants received custodial sentences, the majority being between 3 and a half to 20 years a(see State treatment of specific ethnic groups - Montagnards (or Degar)).

3.3.6 UN Special Rapporteurs expressed concern about the government’s immediate response to the attacks with reports of arbitrary arrests, extrajudicial killings, torture and deaths in custody and the subsequent increase in the surveillance, harassment and intimidation of the Montagnard ethnic group (see State treatment of specific ethnic groups- Montagnards (or Degar)).

3.3.7 Data on the number of Montagnards recorded as being detained varies depending on the source. At the time of writing in December 2024 there were 39 Montagnards recorded as detained across various databases. The details of those detained show all were detained in relation to the religious activity, with nearly all detainees charged with ‘undermining national unity’(see sections below on Catholics and Protestants, State treatment of specific ethnic groups- Montagnards (or Degar) and State treatment of specific religious groups- Catholics and Protestants ).

3.4 Hmong

3.4.1 Members of the Hmong ethnic group are unlikely to face persecution or serious harm from the state on the basis of their ethnicity alone. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.4.2 Members of the Hmong ethnic group who are additionally members of the Protestant Duong Van Minh religious group are likely to face persecution or serious harm from the state.

3.4.3 There are approximately 1.3 million Hmong in Vietnam, and they traditionally inhabit the northern and central highlands, with the majority of those residing in rural areas (see Ethnic groups - Hmong).

3.4.4 The Hmong are mainly non-religious but approximately 247,000 (19% of their population) are Protestant and a small number around 13,000 (1%) are Catholic (see Ethnic groups - Hmong).

3.4.5 Like the Montagnards the Hmong have historical links to the US and are viewed with suspicion by the Vietnamese government. Hmong groups have, in the past, been involved in political protests demanding religious freedom and autonomy (see Ethnic groups - Hmong).

3.4.6 The law requires a birth certificate in order to access public services but thousands of Hmong lack identification papers with the majority of the recorded 30,000 stateless people belonging to the Hmong ethnic group (see Treatment of ethnic groups - Documentation).

3.4.7 The Hmong have been affected by the government’s suppression of the Protestant Duong Van Minh religious group, see also the section on Protestants (see State treatment of specific religious groups - Protestants).

3.5 Khmer Krom

3.5.1 Members of the Khmer Krom ethnic group are unlikely to face persecution or serious harm from the state on the basis of their ethnicity alone. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.5.2 There are approximately 1.3 million Khmer Krom in Vietnam, with the majority living in rural areas in the Mekong delta region (see Ethnic groups - Khmer Krom).

3.5.3 Just over half of all Khmer Krom are non-religious with just under half following Buddhism (see Ethnic groups - Khmer Krom).

3.5.4 Khmer Krom activists who try to promote the rights of indigenous people have faced restrictions on freedom of movement, assembly, expression and harassment. In 2023 at least 6 Khmer Krom were arrested for distributing UN documents on human rights, including Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People. Following these arrests 3 were convicted of “abusing democratic freedoms” and sentenced to 2-4 years in prison (see Treatment of specific ethnic groups - Khmer Krom and Treatment of specific religious groups - Buddhists).

3.6 Religious groups

3.6.1 The constitution allows for religious freedom and states that all religions are equal before the law, although Vietnam is officially an atheist state (see Constitution).

3.6.2 The number of religious adherents varies according to sources with the Government Committee for Religious Affairs (GCRA) stating that 27% of the population follow a religion. Although they also state that 90% of the population follows some sort of faith tradition. The US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) provides a lower estimate of 14% of the total population adhering to a religion. Some religious followers may choose not to officially declare their faith making accurate estimates difficult however, the census data between 2019 and 2021 shows the number of religious adherents who self-reported to have more than doubled to 26.5 million in 2021 (see Religious groups - Religious demography).

3.6.3 Where a person is a member or perceived to be a member of a group who the government believes to have separatist aims or has been involved in advocating for land rights, decision makers should refer to the Country Policy and Information Note on Vietnam: Opposition to state.

3.6.4 If the person is a member of an ethnic group, then reference should be also made to the relevant assessment of risk in sections 3.2-3.5. The assessment of risk to individual groups has been based on a wide range of sources, including analysis of data from various databases. For information on how this was collated and analysed see About the country information.

3.6.5 Each case will need to be considered on its facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate that they are at risk of persecution.

3.6.6 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3.7 Registered religious groups

3.7.1 Members of registered religious groups are unlikely to face persecution or serious harm from the state on the basis of their religion alone. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.7.2 The government recognises 38 religious organisations that are affiliated with 16 distinct religions. According to the law, a religious organisation is defined as a religious group if they have received legal recognition from the authorities. Religious groups can apply for recognition once they have operated for at least 5 years. They are required to submit an application to the provincial or national level GCRA and must include details of their location, structure, membership, history, judicial records and summary of their religious doctrines and activities (see Law on belief and religion - Legal status of religious groups and Registration process).

3.7.3 The government restricts some religious activities and intervenes in the appointment of leaders for some religious organisations. Whilst some activities, require advance approval, certain activities, such as conducting routine religious activities are allowed after notifying the appropriate authority. Registered groups are generally able to operate and believers are able to practise their faith without interference from the state, as long as they comply with regulations and local attitudes and interests and are not a perceived threat (see Treatment of religious groups - Religious activities of registered groups).

3.7.4 Where a person is a member or perceived to be a member of a group who the government believes to have separatist aims or has been involved in advocating for land rights, decision makers should refer to the Country Policy and Information Note on Vietnam: Opposition to state.

3.7.5 If the person is a member of an ethnic group, then reference should be also made to the relevant assessment of risk in sections 3.2-.3.5.

3.8 Unregistered religious groups

3.8.1 Members of unregistered religious groups are unlikely to face persecution or serious harm from the state on the basis of their religion alone. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.8.2 Members of unregistered religions who also belong to an ethnic minority group, who promote religious freedom or are involved in activities which are perceived by the government to advocate separatism and who come to the attention of the authorities are likely to face persecution or serious harm from the state.

3.8.3 Unregistered, unrecognised, independent religious groups can apply to the commune-level peoples committee for permission for specific religious activities, although some groups faced difficulty registering and delays to or denials of their applications (see Treatment of unregistered groups).

3.8.4 Members of unregistered religious groups face official discrimination. Unregistered groups state that they face monitoring, denial of identification papers, arrest and disruption to their religious services. This is more likely in ethnic minority groups as they are often perceived to engage in political or human rights advocacy (see Treatment of unregistered groups).

3.9 Buddhists

3.9.1 The estimated number of Buddhists in the country is 14 million. Buddhism is the major religion in Vietnam and is found throughout the country with Mahayana Buddhism the main faith of the Kinh ethnic majority. Theravada Buddhism is the main religion of the Khmer ethnic group (see Religious groups - Buddhists).

3.9.2 Buddhist groups are divided into those who are registered with the government and those who are unregistered. The Vietnam Buddhist Sangha is the government registered Buddhist group in Vietnam (see Religious groups - Buddhists).

3.9.3 Generally, those who are members of registered Buddhists groups are able to practice their religion freely without government intervention (see State treatment of specific religious groups- Buddhists).

3.9.4 Unregistered Buddhists, particularly those from ethnic minorities such as the Khmer Krom, face pressure to join the state registered Buddhist group. Unregistered Buddhists generally face more interference in their ability to practise their religion freely than registered groups and can also be subject to arrests, property seizure, disruption to their religious activities and destructions of their Buddhist temples (see State treatment of specific religious groups - Buddhists).

3.9.5 At the time of writing in December 2024 there were 10 Buddhists recorded as detained. Most of those detained were from the majority Kinh ethnic group and were charged with ‘carrying out activities aimed at overthrowing the Peoples Administration’. However, the 4 most recent detentions from 2023 were all from the ethnic Khmer Krom minority group and charged with ‘abusing democratic freedom’ (see State treatment of specific religious groups - Buddhists).

3.9.6 For an assessment of risk to Hoa Hao Buddhists please see the country policy and information note Vietnam: Hoa Hao Buddhism.

3.10 Catholics

3.10.1 There are more than 7 million Catholic followers in Vietnam and whilst Catholic followers reside in most provinces the highest concentration of Catholic followers is in central Vietnam (see Religious groups- Catholics).

3.10.2 Most Catholics are able to worship freely, mainly in churches although some groups, particularly those outside of cities, worship in the homes of followers (see Religious groups - Catholics).

3.10.3 In general relationships between the government and the Catholic Church are cordial. However, issues can arise where Catholics become involved in areas the government views as politically sensitive, such as land disputes (see Treatment of specific religious groups - Catholics).

3.10.4 Catholic leaders and some Catholic leaders from ethnic minority areas face harassment. Ethnic minority Catholic groups, especially the Montagnard in the Central Highlands, suffer from pressure to recant, confiscation of land, imprisonment, and suppression of their religious groups. At the time of writing in December 2024 there were 10 Catholics recorded as detained. All of those recorded as detained were Montagnards belonging to the Ha Mon religious group and were charged with ‘undermining national unity policy’ (see Treatment of specific religious groups - Catholics).

3.11 Protestants

3.11.1 There are an estimated 1.2 million Protestants with most members being from an ethnic minority (see Religious groups - Protestants).

3.11.2 There are registered and unregistered Protestant groups. The government recognises 11 Protestant organisations, which include Evangelical, Baptist and Gospel churches (see Religious groups - Protestants).

3.11.3 Registered Protestant groups are generally able to operate without government interference but there have been instances where local authorities have prevented some groups from assembling or registering their organisation (see State treatment of specific religious groups - Protestants).

3.11.4 People associated with unregistered Protestant groups generally face more difficulties and restrictions on religious freedom than members of registered Protestant groups, including in relation to freedom of movement and assembly. Unregistered groups however do operate within the country and can apply for permission to conduct specific religious activities, although local authorities sometimes interpret and enforce the law differently. Some people from unregistered groups can face pressure to renounce their faith or join state sanctioned Protestant groups. (see Treatment of unregistered groups and State treatment of specific religious groups - Protestants).

3.11.5 Unregistered religious groups from ethnic minorities may face additional issues related to their perceived political activism. In December 2023 the Bac Kan provincial government stated they had complied with the government directive to ‘eradicate’ the Protestant Hmong religious group Duong Van Minh as they believe they plan to establish an independent Hmong state (see also section on Hmong). This has included people being forced to renounce their faith and the removal of religious altars from homes (see State treatment of specific religious groups - Protestants and State treatment of specific ethnic groups - Hmong).

3.11.6 At the time of writing in December 2024 there were 32 Protestants recorded as detained. 28 of those belonged to the Montagnard ethnic group, with the majority detained in relation to their affiliation with the Degar Protestant Church, a movement not approved by the government with most charged with ‘undermining national unity policy’. 4 were arrested due to their attendance at the funeral of the religious leader Duong Van Minh (see State treatment of specific religious groups - Protestants and State treatment of specific ethnic groups - Montagnards (or Degar)).

3.11.7 Ethnic minority Protestants, especially the Montagnard in the Central Highlands, suffer from surveillance, pressure to recant, arbitrary detention and imprisonment (State treatment of specific religious groups - Protestants and State treatment of specific ethnic groups - Montagnards (or Degar) and Hmong).

3.12 Cao Dai

3.12.1 There are approximately 1.04 million Cao Dai adherents in Vietnam. There are registered and unregistered Cao Dai groups. The government recognises 10 Cao Dai congregations and one Cao Dai sect. Registered groups can generally practise freely without state interference. (see Religious groups- Cao Daoists).

3.12.2 People associated with unregistered Cao Dai groups generally face more difficulties being able to practice their religious worship than members of registered Cao Dai groups. Unregistered groups have been subject to harassment from the authorities, which can include disruption of their religious worship, and confiscation of their property (see Cao Daoists).

3.12.3 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 A person who has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state is unlikely to obtain protection.

4.1.2 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they are unlikely to be able to relocate to escape that risk.

5.1.2 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This section contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

The COI included was published or made publicly available on or before 10 December 2024. Any event taking place or report published after this date will not be included.

CPIT have used the 88 Project ‘Database of persecuted activists in Vietnam’, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom’s ‘Frank R Wolf Freedom of Religion or belief Victims List’ and the Campaign to Abolish torture in Vietnam’s list of ‘Montagnard Prisoners of Conscience’ within the COI. CPIT have cross referenced these databases, checking the personal details of those listed including the arrest dates, release dates and details of sentences to produce tables showing those who are, at the time of writing in December 2024, recorded as detained on at least one of the databases. The information contained on in the tables is the same across all 3 databases unless otherwise stated.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Ethnic groups

7.1 Demography and geography

7.1.1 Vietnam has an estimated population of just over 105 million (2024 est.), with over 85% belonging to the Kinh (Viet) ethnic group[footnote 1].

7.1.2 The UN Women report ‘Figures on Ethnic minority women and men in Viet Nam - From the findings of Surveys on the socio-economic situation amongst 53 Ethnic Minority Groups 2015-2019’ (the UN Women report) published in 2021 noted that:

‘According to the findings of the Population and Housing Census as of April 1, 2019, the population of Viet Nam amounted to 96.2 million, of which the Kinh ethnicity accounted for 85.3% and the other 53 ethnic minorities represented 14.7%. The actual population size of the 53 ethnic minorities was 14.1 million….

‘Amongst the 53 ethnic groups, only six had a population size of over 1 million people, including the Tay ethnic group of 1.85 million people…, those of Thai ethnicity of 1.82 million people…, Muong ethnicity were 1.45 million people…, Mong ethnicity were 1.39 million people…, Khmer ethnicity of 1.32 million people…, and those of Nung ethnicity constituted 1.08 million people…

‘… In the period from 2009 to 2019, the population size of the 53 ethnic minorities increased by nearly 1.9 million people, with the average annual population growth rate of +1.42%, higher than the corresponding rates of +1.09% for the Kinh ethnicity and of +1.14% for the whole country.’[footnote 2]

7.1.3 The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Country Information Report Vietnam, compiled from a range of sources and on the ground knowledge, published in January 2022 (the 2022 DFAT report), noted:

‘About 85 per cent of Vietnam’s population is ethnically Kinh, according to 2019 census data. The remaining 15 per cent of the population is comprised of 53 other recognised ethnic groups, 11 of which have fewer than 5,000 people. The Kinh traditionally live in the coastal and low-lying areas while ethnic minorities are a larger proportion of the population in the Northwest, Central Highlands and areas of the Mekong Delta. Ethnic minority groups, while mostly associated with remote and mountainous regions, also live in other parts of the country because of internal migration.’[footnote 3]

7.1.4 The US State Department (USSD), ‘2023 Report on International Religious Freedom’ (the 2023 USSD RIRF), noted that: ‘Ethnic minorities constitute approximately 14 percent of the population. Based on adherents’ estimates, two-thirds of Protestants are members of ethnic minorities, including groups in the Northwest Highlands (H’mong, Dzao, Thai, and others) and in the Central Highlands (Ede, Jarai, Sedang, and M’nong, among others). The Khmer Krom ethnic group overwhelmingly practices Theravada Buddhism.’[footnote 4]

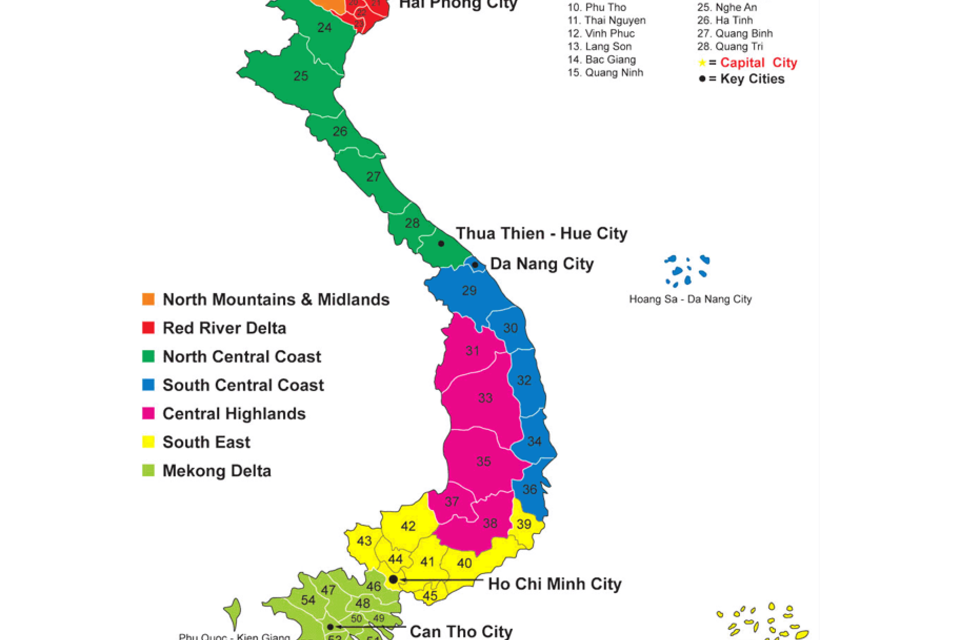

7.1.5 The below map shows the different regions and provinces within Vietnam[footnote 5].

Map showing the different regions and provinces within Vietnam.

7.1.6 The World Bank in their report ‘Improving Agricultural Interventions Under the New National Target Programs in Vietnam’, published in 2020 noted that: ‘About 53 percent of Vietnam’s ethnic minority population lives in the Northern Midlands and Mountain region. Within this region, ethnic minorities account for 56 percent of the population and 98 percent of poor people. The South East and Mekong River Delta regions together account for 56 percent of the country’s population but have less than a tenth of the ethnic minority population between them.’[footnote 6]

7.1.7 The UN Women report noted that:

‘According to the findings of the Population and Housing Census, as of April 1, 2019, ethnic minority people reside in villages and hamlets in 5,453 communes, 463 districts, 51/63 provinces/cities across the country. Almost 90% of ethnic groups live in ethnic minority areas. The Census goes on to show 86.2% of ethnic groups are residing in rural areas and 13.8% in urban areas. By socio-economic region, ethnic minority people live mostly in the Northern Midlands and Mountainous areas accounting for more than 7 million people (49.8%); followed by the Central Highlands with 2.2 million people (15.6%); and North and South-Central Coasts with 2.1 million people (14.7%). The Red River Delta region has the lowest number of resident ethnic minorities, with nearly 0.5 million people (3.3%). The province with the largest ethnic minority population is Son La, with more than 1 million people (7.4%); Ha Giang with more than 0.7 million people (5.3%) and Gia Lai with nearly 0.7 million people (5%).’[footnote 7]

7.1.8 Open Development Vietnam, a coalition of organisations looking into development trends in the Mekong region[footnote 8], noted in an article published in August 2023 that: ‘[Ethnic Minority] EM peoples reside in large areas, except for the Cham, Chinese, and Khmer ethnic groups residing in the plains. Most EMs live in mountainous, highland, and remote regions, concentrated along the northern and western borders of the country.’[footnote 9]

7.1.9 See also Religious demography

7.2 Chinese (Hoa or Han)

7.2.1 According to Minority Rights Group, a ‘human rights organisation working with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples worldwide’[footnote 10]: ‘Most Hoa are descended from Chinese settlers who came from the Guangdong province from about the eighteenth century, and it is for this reason that most of them today speak Cantonese, though there is also a large group who speak Teochew. The majority of ethnic Chinese today live in the south, with a large number living in Ho Chi Minh City.’[footnote 11]

7.2.2 According to the Joshua Project, a US-based research project that gathers ethnological data to support Christian missions abroad[footnote 12], most people from the Chinese Hoa/Han ethnic group are not religious. Those that are religious are more likely to follow ethnic religions or Buddhism[footnote 13].

7.2.3 Using the Government Statistic Office (GSO) 2019 population and housing census, CPIT have put the population numbers and breakdown of urban/rural population for the Hoa ethnic group into the table below[footnote 14].

| Total population | Urban population | Rural population |

|---|---|---|

| 749,466 | 522,327 | 227,139 |

7.2.4 CPIT have used data from Open Development Vietnam to show the distribution of religion within the Hoa ethnic group. Open Development used data from the GSO Results of the 53 ethnic minorities socio-economic census 2019 to compile their data[footnote 15].

| Religion distribution of Hoa ethnic group (%) | |

|---|---|

| Buddhist | 11.8 |

| Catholic | 1.05 |

| Protestant | 0.22 |

| No religion | 86.85 |

7.3 Montagnards (or Degar)

7.3.1 The 2022 DFAT report noted:

‘The Degar or Montagnards (French: ‘mountain dweller’) are a group of more than 30 indigenous highlander communities with distinct cultures and ethnicities, with a combined total population of 1 to 2 million people. They are split between unrelated Austronesian and Mon-Khmer ethnic groups. The Montagnards have long been considered a sensitive group by the Government after they fought alongside American and South Vietnamese troops in the Vietnam war, and following protests in 2004 for land rights and the freedom to practise their Protestant religion.’[footnote 16]

7.3.2 According to the Montagnard Human Rights Organization (MHRO), among the Montagnards there are over 28 tribal groups with the five major tribes being: Bahnar, Jarai, Rhade, Koho and Mnong[footnote 17].

7.3.3 Using the GSO 2019 population and housing census CPIT have put the population numbers and breakdown of urban/rural population for the 5 major tribal groups within the Montagnard ethnic group into the table below[footnote 18].

| Montagnard tribal group | Total population | Urban population | Rural population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gia Rai (Jarai) | 513,930 | 53,951 | 459,979 |

| E De (Rhade or Ede) | 398, 671 | 44,310 | 354,361 |

| Ba Na (Bahnar) | 286,910 | 30,182 | 256,728 |

| Co Ho (Koho) | 200,800 | 22,235 | 178,565 |

| Mnong | 127,334 | 7,930 | 119,404 |

7.3.4 CPIT have used data from Open Development Vietnam to show the distribution of religions for the 5 major tribal groups within the Montagnard ethnic group[footnote 19].

| Tribe | Catholic % | Protestant % | Brahmanism % | Adventism % | Buddhist % | No religion % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gia Rai | 16.14 | 26.07 | 0.17 | 0 | 0.23 | 57.31 |

| Ede | 9.18 | 33.45 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.26 | 56.89 |

| Ba Na | 32.24 | 13.65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53.98 |

| Co Ho | 39.35 | 39.67 | 0 | 2.99 | 0.77 | 17.19 |

| Mnong | 27.78 | 37.12 | 0 | 0.59 | 0.31 | 34.19 |

7.3.5 See also Catholics and Protestants

7.4 Hmong

7.4.1 The Hmong are also referred to as Mong, Na Mieo, Meo, Mieu Ha and Man Trang and tend to reside in northwest areas of Vietnam[footnote 20].

7.4.2 The 2022 DFAT report stated:

‘The Hmong are an ethnic group who speak mutually intelligible languages. They live in the northern and central highlands of Vietnam, traditionally across the borders of Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and China, and they may have Chinese surnames such as “Li” and “Yang”. Like the Montagnards, the Hmong are mostly Evangelical Christian (though other forms of Christianity exist among the Hmong, including Catholicism). Some Hmong retain indigenous beliefs, including ancestor worship, and some syncretic practices also exist.

‘Like the Montagnards, the Hmong have historical links to the US through the Vietnam War era, when some Hmong were reportedly recruited by the Central Intelligence Agency. Hmong groups have also participated in political protests, notably protests in Dien Bien Province in 2011 that saw thousands of Hmong demand religious freedom, land rights and autonomy.

‘Hmong people will often speak various dialects of the Hmong language that are mutually intelligible with Hmong from different communities and across borders. The Vietnamese Hmong dialect is taught in schools, but many Hmong prefer to use the international version. Hmong people have access to healthcare and education, but it is limited practically because of distance and remoteness.’[footnote 21]

7.4.3 Using the GSO 2019 population and housing census, CPIT have put the population numbers and breakdown of urban/rural population for the Hmong ethnic group into the table below[footnote 22].

| Total population | Urban population | Rural population |

|---|---|---|

| 1,393,547 | 45,175 | 1,348,372 |

7.4.4 CPIT have used data from Open Development Vietnam to show the distribution of religion among the Hmong (referred to as Mong in the Open Development data)[footnote 23].

| Religion distribution of Hmong ethnic group (%) | |

|---|---|

| Catholic | 1.48 |

| Protestant | 19.16 |

| No religion | 79.14 |

7.4.5 See also Protestants.

7.5 Khmer Krom

7.5.1 The Khmer Krom, also known as the Kho Me, mostly reside in the Mekong Delta area of Vietnam[footnote 24].

7.5.2 According to Minority Rights Group:

‘The Khmer Krom (literally, the “Khmer from Below” (the Mekong)) mainly inhabit the Mekong delta region in the south-west of Vietnam. They are one of the largest minorities in Vietnam, numbering over 1.26 million, and are the remnants of the society that existed prior to the take-over of the Mekong delta by the Vietnamese in the eighteenth century. Their language, Khmer, is part of the larger Mon-Khmer language family and most are adherents of the Khmer style of Theravada Buddhism, which contains elements of Hinduism and ancestor-spirit worship, whereas most Vietnamese are Mahayana Buddhists.’[footnote 25]

7.5.3 Using the GSO 2019 population and housing census CPIT have put the population numbers and breakdown of urban/rural population for Khmer Krom ethnic group into the table below[footnote 26].

| Total population | Urban population | Rural population |

|---|---|---|

| 1,319 652 | 310,776 | 1,008 876 |

7.5.4 CPIT have used data from Open Development Vietnam to show the religion distribution of the Khmer Krom (referred to as Kho Mein the Open Development data)[footnote 27].

| Religion distribution of Khmer Krom ethnic group (%) | |

|---|---|

| Buddhist | 49.15 |

| No religion | 50.29 |

7.5.5 See also Buddhists

7.6 Poverty and access to services

7.6.1 An Asia Times article from March 2023 noted:

‘Extreme poverty fell from 49% in 1992 to about 4% in 2021, and according to the new multidimensional poverty (MDP) index, multidimensional poverty is now close to 9%. Vietnam was the first country in the Asia-Pacific region to adopt MDP measures, using them since 2015 to monitor poverty and formulate and implement policy. According to the World Bank, the MDP index captures the percentage of households in a country deprived along three dimensions of well-being – monetary poverty, education, and basic infrastructure services.

‘… Among those experiencing chronic poverty, ethnic minority populations are disproportionately over-represented. Comprising about 15% of the population, they account for 90% of the country’s extreme poor, and more than 50% of people suffering from multidimensional poverty. Their average income is only 40-50% of the national average.

‘… For minorities, access to basic social services falls below the national average. More than 30% of minority students do not enter school at the right age, and for some minorities access to services and jobs is challenging, as they are not fluent in Vietnamese.’[footnote 28]

7.6.2 Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2024 Vietnam Country report, which covers the period from 1 February 2021 to 31 January 2023 and assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of governance in 137 countries[footnote 29], noted:

‘The income and wealth gap between the majority ethnic group (Kinh) and most ethnic minorities remains large.

‘… Ethnic minorities, migrants and rural residents are much poorer and have more limited access to services than Kinh and urban residents. They are also de facto discriminated against in terms of access to high-quality education and, within the limits of the party-state, public office.’[footnote 30]

7.6.3 Vietnam VN, an online platform run by the Ministry of Information and Communications of Vietnam, comprised of information from major press agencies and electronic portals of provinces/cities to provide information about Vietnam in many languages[footnote 31], noted in August 2024 that:

‘According to the Ministry of Labor, War Invalids and Social Affairs, the National Target Program for sustainable poverty reduction for the period 2021-2025 has initially reduced the average rate of poor households by 1-1,5%/year; The poverty rate of ethnic minority households decreased by over 3%/year (in poor districts only, the poverty rate decreased by 4-5%/year).

‘With focused investment in improving infrastructure systems, transportation, electricity, roads, schools, and stations, the face of rural areas in ethnic minority and mountainous areas has seen a clear change. Concrete roads have been built to most highland commune centers; Irrigation works, national electricity grids, schools, and medical stations are also invested in new construction and repair; Communications, Internet, and mobile telecommunications networks are widely covered in every village and ethnic minority area.

‘By 2023, 100% of mountainous communes and ethnic minority areas will have electricity from the national grid; Over 98% of communes have public telephone contact points; more than 3,000 public telecommunications access points for people; The mobile phone network has covered all ethnic minority areas with 4G mobile broadband network coverage reaching 99.8% of the total population.’[footnote 32]

7.6.4 The UN Women Report noted that despite improvement in recent years:

‘There are 15 ethnic minority groups which travel a distance of 10 km to less than 20 km to markets and trade centers. Under the road conditions in the mountainous and forest areas, difficulties of the means of transport and no guaranteed safety and security makes travel highly problematic and unreliable. Moreover, a large number of EM women do not know how to ride a motorbike, so a distance of more than 10 km to access services remains a challenge…The remote distance from home to schools, hospitals, markets, etc. can present barriers for EM women and girls in accessing basic social services such as education, health care and participation in social and community activities. Some of the reasons which contribute to this situation include: EM women who own and use a personal means of transport such as cars, motorcycles, bicycles, horses, etc. remains less than men, while public transport is not yet developed in ethnic minority areas. In addition, travel on mountainous roads and paths presents dangerous elements that pose a threat to the security and safety of women and girls such as human trafficking, abuse, robbery, etc. These challenges have made women and girls of ethnic minorities living in remote, hard-to-reach and isolated areas experience greater disadvantages in accessing basic social services.’[footnote 33]

8. Legal status of ethnic groups

8.1.1 There are 54 ethnic groups recognised by the Vietnamese government[footnote 34] with 53 of them being minority ethnic groups[footnote 35]. The law prohibits discrimination against ethnic minorities[footnote 36].

8.1.2 Article 5 of the Constitution states:

‘1. The Socialist Republic of Vietnam is the unified State of all nationalities living together in the country of Vietnam.

2. All the ethnicities are equal, unified and respect and assist one another for mutual development; all acts of national discrimination and division are strictly forbidden.

3. The national language is Vietnamese. Every ethnic group has the right to use its own language and system of writing, to preserve its national identity, to promote its fine customs, habits, traditions and culture.

4. The State implements a policy of comprehensive development, and provides conditions for the ethnic minorities to promote their physical and spiritual abilities and to develop together with the nation.’[footnote 37]

8.1.3 The USSD 2023 Country Report on Human Rights Practices, published in April 2024 and covering events in 2023 (The USSD 2023 report on Human Rights Practices) noted that: ‘The constitution recognized the rights of members of ethnic minorities to use their languages and protect and nurture their traditions and cultures.’[footnote 38]

8.1.4 The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), a network of researchers and human right activists who document the situation of Indigenous Peoples and advocate for an improvement of their rights[footnote 39], noted in their annual report for 2024 that:

‘Vietnam is a party to seven of the nine core international human rights instruments and continues to consider the possibility of acceding to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED) and the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICRMW). Vietnam has not ratified [International Labour Organization] ILO Convention 169 and, although Vietnam voted in favour of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), it does not recognize ethnic minorities as Indigenous Peoples.’[footnote 40]

8.1.5 The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples guarantees various rights to Indigenous people in particular:

-

‘Article 3 Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

-

‘Article 4 Indigenous peoples, in exercising their right to self-determination, have the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs, as well as ways and means for financing their autonomous functions.’[footnote 41]

8.1.6 Article 58 of the Constitution states: ‘The State and society shall make investments to further the protection of and care for the People’s health, implement the universal health insurance, and adopt policies to prioritize health care for ethnic minority people and people living in mountainous areas, on islands, and in areas that have extremely difficult socio-economic conditions.’[footnote 42]

9. Treatment of ethnic groups

9.1 Government policies

9.1.1 Open Development Vietnam noted that:

‘The Government’s most recent policy on ethnic minorities, released in 2016, is the “Decision on Typical Support Policies for Socio-economic Development of Ethnic Minorities and Mountainous Areas 2017-2020”. In addition, a series of National Target Programs [NTP] for Poverty Reduction have been implemented, in which ethnic minorities are the main beneficiary group … Recently, the NTP on New Rural Development also addresses the ethnic minorities in remote mountainous areas. The overall objective of these policies is to foster sustainable poverty reduction and narrow the gaps between ethnic regions and other regions of the country while protecting and preserving ethnic cultures and customs.’[footnote 43]

9.1.2 The 2022 DFAT report noted: ‘Some concessions exist for ethnic minorities; for example, they might receive legal assistance, land grants or subsidised specialist education. Subsidies are available to businesses who invest in areas with large ethnic minority populations. In spite of these efforts, many ethnic minority communities are very poor. The World Bank estimates that 86 per cent of Vietnam’s poor are from ethnic minorities.’[footnote 44]

9.1.3 The USSD 2023 report on Human Rights Practices noted that: ‘By law education was free, compulsory, and universal through age 14, but school fees were common. Under a government subsidy program, ethnic minority students were exempt from paying school fees.’[footnote 45]

9.1.4 On 18 January 2024 at its 5th Extraordinary Session, the 15th National Assembly voted to approve a revised Land Law. The changes to the 2013 Land Law include the allocation of land and support for landless communities and those with insufficient land[footnote 46]. The IWGIA World report for 2024 noted that:

‘… the draft law introduces special provisions to deter violations of land policies concerning ethnic minorities, for example, the unauthorized transfer of land-use rights. …The final version of the draft is… more sensitive to the conditions, customs, and cultural identity of the diverse peoples of Vietnam, including provisions to support ethnic minorities in developing their economy under the forest canopy.’[footnote 47]

9.1.5 The Vietnam delegation told the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in their ‘Report of the working group on the Universal Periodic Review - Vietnam’, published in June 2024 that:

‘The 2021–2025 national target programme for sustainable poverty reduction, with a budget of $ 3 billion, was specifically targeting ethnic minorities and those in mountainous areas. In 2023, the nationwide multidimensional poverty rate had decreased to 5.71 per cent, a decline of 1.49 percentage points compared to 2022 and that of ethnic minorities had reached 16.5 per cent, a decrease of more than 4 percentage points.

‘… The 2021–2030 national target programme for ethnic minorities and those mountainous areas was the first such dedicated programme, with a budget of $ 5.6 billion. Viet Nam placed great importance on the preservation of cultural heritage and writing and teaching in the languages of ethnic minorities. Following its dialogue with the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination on its combined fifteenth to seventeenth periodic reports on implementation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, held in November 2023, Viet Nam planned to issue a comprehensive plan to raise awareness and implement the recommendations of the Committee by the end of 2024.’[footnote 48]

9.1.6 See also Poverty and access to services

9.2 Documentation

9.2.1 The 2022 DFAT report noted:

‘There is a significant backlog for applications in ethnic minority communities. Fewer members of ethnic minority communities have documentation, relative to the general population, which may be caused by language differences and distrust among those communities of the process. UNICEF estimated in 2016 (most recently available estimate) that about 359,000 children under the age of five were not registered, the majority of whom were living in a ‘hard to reach area’, particularly the remote mountains. Birth certificates are required to access education and healthcare for children and a household registration is required to obtain a birth certificate, which means that minority children may be denied access to services in practice.’[footnote 49]

9.2.2 In a joint submission to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (UN CERD) published in September 2023, the Boat People SOS (BPSOS), Evangelical Church of Christ of the Central Highlands (ECCCH), Montagnards Stand for Justice (MSFJ) and H’mong for Human Rights noted:

‘While the Vietnamese Government did take action following the 2012 Concluding Observation, the changes made were superficial and failed to rectify the stateless predicament. From January 1, 2023, household registration books are no longer considered valid documents, based on the Law on Residence 2020. However, this alteration did not significantly impact the lives of these ethnic groups; instead, it introduced several loopholes that perpetuate their stateless condition. Subsequent to the abolition of the household registration, individuals are expected to rely on the following documents for identification:

-

Citizen Identification Card (Căn cước công dân);

-

Identity card (Chứng minh nhân dân);

-

Certificate of residence information (Giấy xác nhận thông tin về cư trú);

-

Notice of personal identification number and citizen information in the National Population Database (Giấy thông báo số định danh cá nhân và thông tin công dân trong Cơ sở dữ liệu quốc gia về dân cư).

‘Ironically, acquiring a Citizen Identification Card may still necessitate a household registration if an individual’s information is not already in the National Population Database. This presents a significant hurdle for individuals, particularly the H’Mong and Montagnard (Degar) ethnic groups who lacked household registrations previously, as they remain unable to obtain national IDs, perpetuating their precarious situation.’[footnote 50]

9.2.3 The USSD 2023 report on Human Rights Practices noted:

‘Many ethnic minority Christians in the Central Highlands reported local authorities denied their passport applications.

‘… According to the [UN High Commissioner for Refugees] UNHCR, there were approximately 30,000 recognized stateless persons and persons of undetermined nationality in the country. In recent years the government increased efforts to identify stateless persons. The bulk of this population were ethnic H’mong living in border areas and undocumented ethnic Vietnamese from Cambodia migrating to Vietnam…

‘… The law required a birth certificate to access public services, such as education and health care. Nonetheless, some parents, especially from ethnic minorities, did not register their children.’[footnote 51]

9.3 State harassment, discrimination and detention

9.3.1 This note provides information on the situation for ethnic minorities and sources often refer to them collectively, but the experiences of each group may differ. Where information is available, the note will refer to and consider the treatment of each group discretely (see State treatment of specific ethnic groups).

9.3.2 Nguyen Dinh Thang, executive director of Boat People SOS, who ‘provide assistance to victims of human rights violations in Vietnam’[footnote 52], told Radio Free Asia in an article published in November 2023 that:

‘… [The] organization plans to denounce the Vietnamese government for implementing religious, economic, and cultural repression policies targeting ethnic groups and minorities such as the Montagnards in the Central Highlands, the H’mong in the north, and the Khmer Krom in the south of Vietnam. “We have had many reports on human rights violations in general, and in fact, the indigenous ethnic groups are the most severely affected, including the Montagnards, the H’mong, and the Khmer Krom,” he said.’[footnote 53] The article didn’t provide any further information on the government policies or examples of any human rights violations.

9.3.3 The UN Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) report ‘Concluding observations on the combined fifteenth to seventeenth periodic reports of Viet Nam’, published in December 2023, noted:

‘The Committee is concerned about reports of persistent racial profiling, torture, ill‑treatment, deaths in custody, abuse of authority and excessive use of force by law enforcement officials against individuals and groups at risk of racial discrimination, as well as those working on the rights of ethnic minorities, Indigenous Peoples and non-citizens, during the investigation led by the Ministry of Public Security following the attacks on the commune police stations in Dak Lak Province on 11 June 2023.

‘… The Committee is concerned by the disproportionate number of individuals belonging to ethnic minority groups charged and convicted under articles 109, 113 and 229 of the Law on Counter-Terrorism (No. 28/2013/QH13) in relation to offences classified as “terrorist”, defined as acts aimed to “oppose the people’s government” or to “cause panic”, including the 81 Montagnards involved in the attacks of 11 June 2023, who were charged and convicted under article 113 of the Criminal Code in relation to terrorism to oppose the people’s government (art. 4).

‘… The Committee is deeply concerned about reports that people working on the rights of ethnic minorities, Indigenous Peoples and non-citizens, as well as leaders of ethno‑religious associations, are systematically targeted using violence, intimidation, surveillance, harassment, threats and reprisals as a consequence of their work. The Committee is particularly concerned by reports of reprisals for cooperating or attempting to cooperate with the United Nations, its representatives and mechanisms in the field of human rights, including the cases of two Montagnards, Y Khiu Niê and Y Sĩ Êban, who attempted to travel to a conference on freedom of religion and belief in 2022, as well as the cases of two Khmers-Krom youths, Duong Khai and Thach Cuong, who were detained by police on three separate occasions between 2021 and 2022, after having translated and disseminated copies of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (art. 5).

‘… The Committee is concerned that, despite its previous recommendation to respect and protect the existence and cultural identity of all ethnic groups, in line with the principle of self-identification, the State party has been reluctant to engage in open and inclusive discussions on the recognition of Indigenous Peoples, including the Khmers-Krom and Montagnards, in line with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Moreover, while noting the ongoing drafting process of the amended Land Law, the Committee is concerned that, in accordance with the present Land Law (No. 45/2013/QH13) and relevant decrees, communities, including those of Indigenous Peoples, are only notified 15 days in advance that their land has been acquired and are subject to relocation, without compliance with the principle of free, prior and informed consent or consultation throughout the development of resettlement plans (arts. 2 and 5).’[footnote 54]

9.3.4 The USSD 2023 report on Human Rights Practices noted that:

‘There were reports, however, that not all members of ethnic minorities were able to engage in decisions affecting their lands, cultures, and traditions. International human rights organizations and refugees continued to allege that authorities monitored, harassed, and intimidated members of certain ethnic minority groups, particularly ethnoreligious minorities in the Central and Northwest Highlands, including Christian H’mong. Authorities used national security laws to impose lengthy prison sentences on members of ethnic minorities for connections to overseas organizations the government claimed espoused separatist aims.’[footnote 55]

9.3.5 The IWGIA noted in their undated profile on Vietnam that:

‘One of the challenges for Indigenous Peoples in Vietnam is land tenure and the allocation of forest land to communities. Policies, laws and regulations related to land and forest tenure vary according to the different provinces of Vietnam. This creates a situation of uncertainty and insecurity for many [Ethnic Minorities] MS, as well as an unequal distribution of land. For example, in 2015, only 26% of the total area of forest land was allocated to households and 2% of that land was allocated to communities for management. However, some communities complained that the quality of the forests allocated to households and communities was low, with no plant cover and difficult to generate income from these forest lands.’[footnote 56]

9.3.6 See also Government policies

9.4 Societal treatment

9.4.1 The UN CERD Concluding observations on the combined fifteenth to seventeenth periodic reports of Viet Nam, published in December 2023 noted:

‘The Committee is concerned about the absence of legislation prohibiting racist hate speech or incitement to racial hatred. The Committee is concerned about the persistent incidents of hate speech and incitement to racial hatred directed at individuals belonging to ethnic and ethno-religious minority groups, … The Committee regrets the lack of information provided by the State party on the existence of legislation recognizing racial discrimination as an aggravating circumstance for all crimes. The Committee is deeply concerned by the persistent hate crimes in the form of attacks committed by “Red Flag Associations”, as well as the lack of information provided on investigations, prosecutions and convictions. The Committee regrets that, in the information provided by the State party, it referred to the individuals who comprise the “Red Flag Associations” as patriots thereby legitimizing their discriminatory actions (art. 4).’[footnote 57]

9.4.2 Freedom House, noted in their Freedom in the World 2024 report, covering events in 2023, that: ‘Members of ethnic and religious minority groups face societal discrimination…’[footnote 58]

9.4.3 The USSD 2023 report on Human Rights Practices noted: ‘The law prohibited violence and discrimination against ethnic minorities, but societal discrimination was longstanding and persistent. The government did not enforce the law effectively. The law did not prohibit discrimination in hiring based on ethnicity.’[footnote 59]

10. State treatment of specific ethnic groups

10.1 Chinese (Hoa or Han)

10.1.1 Open Development Vietnam, noted that: ‘One minority group, the Hoa (ethnic Chinese), is very well assimilated into Vietnamese culture, and are important in the Vietnamese economy. Because of this, they are not usually considered an “ethnic minority”’.[footnote 60]

10.1.2 According to Minority Rights Group International:

‘Not all Chinese (known as Hoa) are officially recognized by the government of Vietnam: the Hoa category excludes the San Diu (mountain Chinese) and the Ngai.

‘The overall situation for Hoa has improved dramatically, especially when compared to the repression, discrimination and loss of property that they experienced before the 1990s. Overall, Hoa Chinese appear to be benefiting from Vietnam’s liberalization of the economy more than other minorities. Indeed, poverty among the Hoa since 1993 has not only decreased more than for any other ethnic minority, it is even lower than the poverty level for majority Kinh.

‘Vietnamese authorities still do not allow private schools teaching in Chinese (Mandarin or Cantonese) to go beyond teaching the actual language. This results in some Hoa parents sending their children to these schools in order to preserve their language and culture rather than to Vietnamese-medium state schools.’[footnote 61]

10.1.3 There was no further information regarding state treatment of Chinese (Hoa or Han) in relation to their ethnicity (see Bibliography).

10.2 Montagnards (or Degar)

10.2.1 This section should be read in conjunction with the section on the state treatment of Protestants and the section on Catholics. Reference should also be made to the Country Policy and Information Note on Vietnam: Opposition to the state for further information on land disputes.

10.2.2 The 2022 DFAT report noted:

‘Land is a particularly sensitive issue for the Montagnards. Traditional land inheritance is facilitated orally between family members and this is not recognised by the state. Land grabbing and development has displaced many Montagnards from their traditional homelands and surrounding natural resources.

‘The Montagnards are majority Evangelical Protestant with some smaller Catholic communities. They may combine their spiritual beliefs with political protest and have been seen by the Government as separatists in the past (for example during protests in the first decade of this century when they demanded greater self-determination and religious freedom).’[footnote 62]

10.2.3 Voice of America (VOA) reported in July 2023 that:

‘Vietnamese authorities reportedly have heightened security and increased the persecution of ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands after a deadly attack last month on government buildings there.

‘The Central Highlands is home to Montagnards, an umbrella term for ethnic minorities native to the region, many of whom identify as Christian. They have historically been at odds with Vietnam’s one-party state and have grievances going back decades, relating to issues including land appropriation and religious persecution. Rights groups and Montagnard refugees living abroad say the government has intensified the crackdown on native highlanders.

‘On June 11 [2023], two groups in the Ea Ktur and Ea Tieu communes of Dak Lak province attacked the local People’s Committee buildings using guns and Molotov cocktails. The incident left nine people dead, including four police officers, two commune leaders, and three residents, according to state media.

‘Rights groups in contact with Montagnards in the region say the attack has exacerbated repression in the region and put Montagnard refugees in nearby Thailand at risk. There are fears the Vietnamese government will use the incident as justification to increase its harsh policing of the region.

‘Authorities responded to the attack in force, bringing in security troops from the Public Security Ministry and the Vietnamese People’s Army.

‘Deputy Public Security Minister Le Quoc Hung on June 12 called the Dak Lak shootings “terrorist acts” with the “instruction and support of hostile parties abroad.” He said the ministry had utilized all its resources to arrest the suspects and seized all weapons from the attack. More than 90 suspects have now been arrested for various crimes including terrorism, according to local media reports.

‘… Although the motive of the attackers is unknown, experts point to the long-running repression of Montagnard rights in Vietnam and a lack of sufficient response from the Vietnamese government.’[footnote 63]

10.2.4 Radio Free Asia (RFA) reported in September 2023 that a government official had stated that land disputes and a growing wealth gap were partly to blame for the Dak Lak attack. The report noted that:

‘… Vice Minister of Public Security Tran Quoc To called the incident “unfortunate,” according to a report by the official Tien Phong (Pioneer) newspaper, and acknowledged that frustration over Vietnam’s growing wealth gap and poor land management by local officials were partly to blame.

‘However, the vice minister, who is also the brother of late President Tran Dai Quang, stressed that “negligence was not the only issue at play” and told the National Assembly Committee reviewing an investigation of the attacks that they were an “inevitable consequence of relentless opposition and sabotage” of the government.

‘The Vietnamese government and state media often refer to peaceful critics of state policies and those who call for greater protections of human rights as “hostile forces” – particularly overseas Vietnamese activists.’[footnote 64]

10.2.5 Radio Free Asia noted in a report from 6 March 2024 that:

‘Vietnam has accused two foreign-based political groups of being “terrorist organizations” that helped plan an attack in Vietnam’s Central Highlands last June leaving nine people dead.

‘The country’s Ministry of Public Security identified them as the United States-based Montagnard Support Group Inc. (MSGI) and Montagnard Stand for Justice (MSFJ), which was formed in Thailand in 2017 and began operating in the U.S. two years later.

‘… MSGI and MSFJ have campaigned for their rights, claiming they struggle to receive official documentation and often lose out in land grabs by local authorities. Many are also harassed and prevented from practicing their religion.

‘Wednesday’s statement from the ministry claimed the two groups recruited and trained people to “carry out terrorist activities, incite protests, kill officials and civilians, sabotage state assets and try to establish their own states.”

‘The claims relate to the attacks on June 11, 2023 when dozens of Montagnards, divided into two groups, attacked the headquarters of the People’s Committee and the police of Ea Tieu and Ea Ktur communes in Dak Lak province. Four police officers, two commune officials, and three civilians died in the attacks.

‘MSFJ co-founder Y Phik Hdok told Radio Free Asia his group never advocated violence. He said it operated peacefully with the goal of fighting for human rights and religious freedom and denied the ministry’s claims.’[footnote 65]

10.2.6 The IWGIA World report 2024 noted in relation to the Dak Lak attacks that:

‘While the motivation and goal of the Dak Lak attackers remains unclear, the Central Highlands is known to be home to around 30 Indigenous Peoples collectively known as Montagnards (sometimes referred to as Dega). For decades, the area has seen tensions between the Kinh people and the Montagnards, as well as protests and clashes targeting the central state, particularly over land, economic difficulties, and crackdowns on evangelical churches. The Vietnamese authorities claim that, during searches related to the case, in addition to weapons, explosives and ammunition, they also seized 10 FULRO flags, further claiming that the assailants aimed to establish an independent Dega state. FULRO – the Front Uni de Lutte des Races Opprimées or the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races – was an armed organization that was dissolved in the early 1990s and which operated in central and southern Vietnam with the objective of achieving autonomy for various Indigenous Peoples and ethnic minorities.’[footnote 66]

10.2.7 On 14 June 2024, in a joint letter sent to the Vietnam government, 13 Special Rapporteurs from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) noted that:

‘Armed attacks on two commune police stations in Dak Lak Province, Central Highlands, on 11 June 2023 killed nine people, including four police officers, two local officials (the Secretary of Ea Ktur commune and the Chairman of Ea Tieu commune) and three civilians, and injured two police officers and a number of others. In response an intense security operation involving heavily armed police and other security units from Viet Nam’s Ministry of Public Security rapidly led to the detention of a large number of people. Local residents were called on by state media to assist the authorities to search for and apprehend persons wearing commonplace “camouflage” clothing, and duly armed themselves with knives, machetes and sticks, leading to individuals being arrested and some being beaten. Some Montagnard residents fled their homes in fear and there were reports of arbitrary arrests, extrajudicial killings, torture, and other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, including of Christian missionaries. The border with Cambodia was closed in cooperation with the Cambodian Government, which declared that anyone crossing the border would be arrested and returned to Viet Nam. Detainees were denied access to lawyers for protracted periods of months following their arrests and were also denied access to family visits.

‘On 20 January 2024, 100 defendants were convicted for their alleged involvement in the attacks by a “mobile court” (xet xu luu dong) of five judges, including the Chief Justice of Dak Lak Provincial People’s Court (verdict 08/2024/HS-ST). The trial was held in Residential Area 11, Ea Tam ward of Buon Ma Thuot city. The trial proceedings took place over a period of five days, with one day of deliberations. Nineteen lawyers were present at the trial to represent the 94 defendants who were present at the trial. However, the six defendants who were tried and sentenced in absentia did not receive legal representation. The Vietnamese authorities claimed that the defendants confessed, expressed remorse, and asked for leniency. The sentences were as follows:

-

Ten defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment for the offence of “terrorism to oppose the people’s government” under article 113 of the Criminal Code of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, Law No. 100/2015/QH13, 27 November 2015;

-

Forty-three defendants received prison sentences of between six to 20 years under the same offence;

-

Forty-five defendants, including six who were tried in absentia, received prison sentences of between three and a half and 11 years for the offence of “terrorism” under article 299 of the Criminal Code 2015;

-

One defendant received a two-year prison sentence for “organizing, brokering others illegally exit, enter or stay in Viet Nam” under article 348 of the Criminal Code 2015; and

-

One defendant received a nine-month prison sentence for “concealment of crimes” under article 389 of the Criminal Code 2015

‘Most of the defendants were indigenous Montagnards … while one is of the majority Kinh ethnic background…The Vietnamese authorities declared that the defendants were incited and directed online by US-based “reactionary” ethnic minority organizations to mount the attack, by forming the armed group “Degar Soldiers”, with the aim to overthrow the Vietnamese government and establish the “Degar State”. The authorities also identified as responsible the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races (Front unifié de lutte des races opprimées) (FULRO), a militant organization founded in 1964 to pursue autonomy of indigenous people and minorities in Viet Nam and dissolved in 1992.

‘… In connection with the 11 June 2023 attack, on 6 March 2024 the Ministry of Public Security listed Montagnards Stand for Justice (MSFJ) (Người Thượng vì công lý) as a terrorist organization. …. MSFJ allegedly engaged the “Degar Soldiers” group to carry out the 11 June 2023 attack, in order to establish a “Degar State”. As a result of the listing, the authorities warn that “anyone who engaged in, propagated, enticed, incited others to participate, sponsored or received sponsorship, or participated in training courses organized by MSFJ, or followed its direction, would be charged with “terrorism” or “supporting terrorism”.

‘MSFJ denies involvement in terrorism or the attack of 11 June 2023 and views the designations as a pretext for suppressing Montagnard groups in exile that document and expose human rights violations against Montagnards in Viet Nam.