Summary report

Published 22 October 2019

Introduction

This briefing summarises an evidence review on the barriers that women face to progression in the workplace and what we know about how to overcome them.

What evidence is this report based on?

The research summarised the evidence from 175 academic papers studying the topic of gender and the workplace.

“Women’s progression in the workplace continues to be held back by tensions between current ways of organising work and caring responsibilities.”

For more information: please see the full report. You can also read guidance on the evidence-based actions you can take to address the barriers to women’s progression.

The gender divide in workplace progression

A steady upward trajectory for men, a plateau in their late 20s for women.

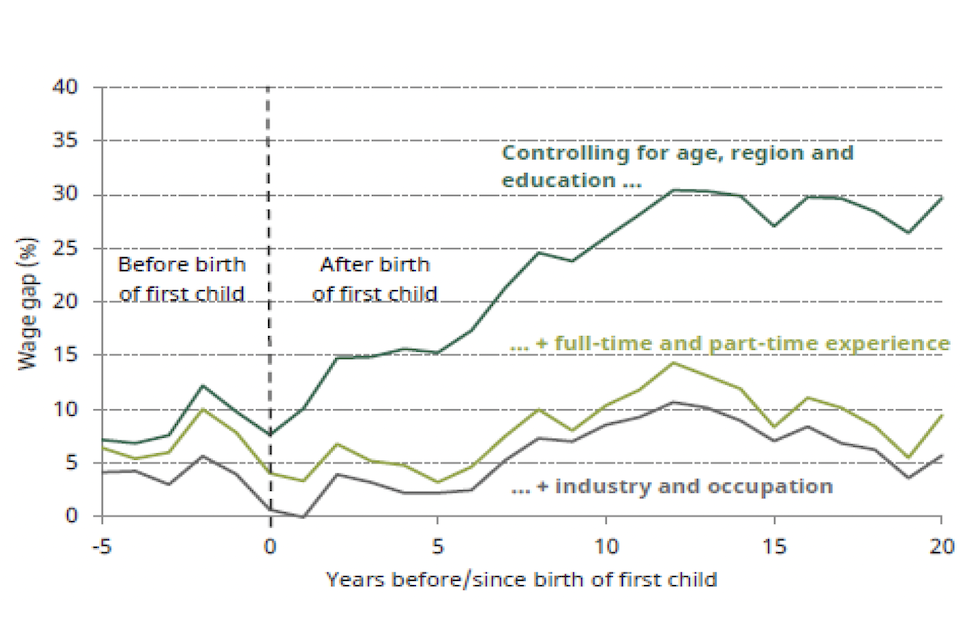

There is very little difference between the wages of men and women when they enter the workplace. From the late 20s and early 30s a large gap appears as women’s wage progression plateaus, and men’s continues to rise. Gender differences in part-time work are important explanations for these differences, but a substantial amount remains unexplained.

Figure 1: Gender wage gap by time to/since birth of first child

Source: Costa a Dias, M., Joyce, R., Parodi, F., 2018. Wage progression and the gender wage gap: the causal impact of hours of work. The Institute of Fiscal Studies

Another key difference is that women who enter the labour market in low-paid jobs experience ‘sticky floors’ – rarely progressing upwards.

By contrast such jobs are ‘springboards’ for men into higher paid positions. This springboard vs sticky floor dichotomy has worsened over time.

Barriers to women’s progression in the workplace

Organisational processes for progression that open up space for bias.

In many workplaces decisions about pay and promotion are made through processes that disadvantage women.

Promotion via networks

Networks can play a key role in deciding who gets certain work assignments and promotions. Some networks are male dominated, especially at the top, and networking events often take place out of hours, making them less accessible to women.

Promotion via social cloning

Those in positions of power often champion those who are like themselves, or who look like the candidates that have gone before. This can lead to a disadvantage for women because women are less likely to possess, or be seen to possess, the relevant qualifications of the archetypal candidate.

Some workplaces lack clear standards for pay and promotion. This makes it harder for employees to know what they need to do to progress, or to realise when they are being undervalued.

In the absence of clear systems:

- decisions are more likely to be made through the processes that disadvantage women listed above

- decision makers are more likely to rely on subjective (and potentially biased) judgements rather than objective indicators based on past performance, when making decisions on pay and promotion

- employees are more likely to be reliant on a patron or sponsor to progress – a requirement that men are more likely to fulfil

“In many workplaces decisions about pay and promotion are made through processes that disadvantage women.”

Interventions to overcome barriers to women’s progression in the workplace

What works to overcome these?

Transparency and formalisation have been found to be successful in reducing gender bias, when combined with senior oversight of these processes.

Changes which make the processes for promotion and progressive standardised and transparent are linked with improved career outcomes for women. This means, for example, formal career planning, clear salary standards and job ladders.

It is also important to ensure that processes are followed. This means:

- training line managers in implementing processes

- senior figures should have oversight of pay and promotion decisions and have the power to challenge them

- taking steps to ensure that objective, rather than subjective criteria are used when making promotion decisions – this could include evaluating candidates for promotion in pairs or groups

Some research suggests that this helps to place focus on criteria that are important, such as performance data, and reduce reliance on instinctive judgement.

What is less successful?

Diversity training to remove bias. There is currently no evidence that diversity or unconscious bias training can have a long-term impact on attitudes or behaviour.

Reliance on out-of-hours mentoring or networking schemes. Mentoring or networking schemes rely on women opting in and devoting extra time to participate, something that won’t be possible for all.

“Transparency and formalisation have been found to be successful in reducing gender bias.”

Conflicts between out of work responsibilities and current ways of working

In many workplaces persistent norms of overwork, expectations of constant availability and excess workloads conflict with unpaid caring responsibilities – the majority of which still fall on women.

Long working hours reduce the possibility of combining work with any external responsibilities.

Alternative ways of working do not currently offer parity

Alternative ways of working, including part-time and flexible work are currently the key solutions to overcome the conflict between current ways of working and caring responsibilities described in the previous section.

However, while the evidence suggests that they are essential in helping women maintain their labour market position after the transition to motherhood, taking advantage of alternative ways of working can lead to a reduced likelihood of career progression.

Part-time work can be difficult to find, and career limiting:

- there continues to be a shortage of quality part-time work and part-time experience offers very little return on experience in terms of wage growth

- while there has been an increase in the proportion of female senior part-timers the evidence suggests this is largely as a result of already senior women negotiating a reduction in hours

Meanwhile part-timers in lower occupational jobs (most of whom are female) receive low wages with limited opportunities for progression.

Emerging evidence suggests there is also the potential for flexible workers to suffer negative career consequences.

“Taking advantage of alternative ways of working can lead to a reduced likelihood of career progression.”

What works to overcome these barriers?

The evidence suggests that without changes to underlying organisational cultures, and while such working practices are taken up only by women, they risk embedding gender inequality in contexts where full-time workers are the norm, and part-time and flexible working is seen as signalling a lack of commitment.

Alternative working time policies need to go alongside efforts to reform organisational culture to include them.

These include destigmatising part-time and flexible work by:

- seeing them as the rule, rather than the exception – advertise all jobs as being available on a flexible and part-time basis

- communicating that work-life policies are for everyone, not just for parents

- showing ongoing top-down commitment to supporting part-time and flexible workers

- senior role models talking openly about balancing work and family life, or who work part-time

They also include supporting line managers to be supportive. Training for line managers can be effective in ensuring that they are able to support flexible and part-time workers. One model is to develop case studies of line managers successfully working with part-time employees.

Another is to provide training to part-time or flexible staff in order to help them rebalance their workload, and then have those staff train their own managers. Training of this sort can also have a positive impact on employee wellbeing.

“Full-time workers are the norm, and part-time and flexible working is seen as signalling a lack of commitment.”