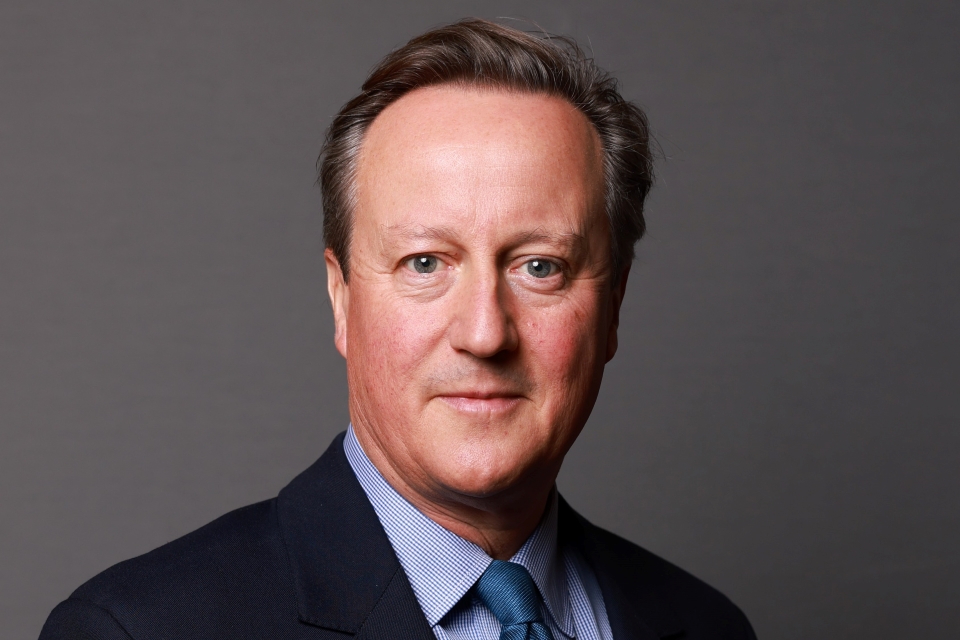

David Cameron's address to the United Nations General Assembly

"I am convinced that we need to focus more than ever on the building blocks that take countries from poverty to prosperity."

Mr President, Deputy Secretary General, Excellencies, Distinguished Delegates, Ladies and Gentlemen.

I am proud that this year Britain welcomed the world to the Olympic and Paralympic games and put on a great display showing that while we may only have the 22nd largest population, we can roll out one of the warmest welcomes in the world.

I am honoured too that in this coming year I have been asked to co-chair the High Level Panel to build one of our greatest achievements with the Millennium Development Goals.

Britain takes this very seriously.

I am convinced that we need to focus more than ever on the building blocks that take countries from poverty to prosperity. The absence of conflict and corruption. The presence of property rights and the rule of law. We should never forget that for many in the world the closest relative of poverty is injustice. Development has never been just about aid or money, but I am proud that Britain is a country that keeps its promises to the poorest in the world.

Mr President, a year ago I stood here and argued that the Arab Spring represented an unprecedented opportunity to advance peace, prosperity and security.

One year on, some believe that the Arab Spring is in danger of becoming an Arab Winter.

They point to the riots on the streets, Syria’s descent into a bloody civil war, the frustration at the lack of economic progress and the emergence of newly elected Islamist-led governments across the region.

But they are in danger of drawing the wrong conclusion.

Today is not the time to turn back - but to keep the faith and redouble our support for open societies, and for people’s demands for a job and a voice.

Yes, the path is challenging. But democracy is not - and never has been - just about simply holding an election. It is not one person, one vote, once. It’s about establishing the building blocks of democracy, the independence of the judiciary and the rule of law, with the majority prepared to defend the rights of the minority, the freedom of the media, a proper place for the army in society and the development of effective state institutions, political parties and wider civil society.

I am not naive in believing that democracy alone has some magical healing power. I am a Liberal Conservative, not a Neo-Conservative. I respect the different histories and traditions that each country has. I welcome the steps taken in countries where reform is happening with the consent of the people. I know that every country takes its own path. And that progress will sometimes be slow.

Some countries have achieved stability and success based on tradition and consent. Others have endured decades in which the institutions of civil society were deliberately destroyed.

Political parties banned. The free media abolished. The rule of law twisted for the benefit of the few. We cannot expect the damage of decades to be put right in a matter of months. But the drive for opportunity, justice and the rule of law and the hunger for a job and a voice are not responsible for the problems in the region. Quite the opposite.

The building blocks of democracy, fair economies and open societies are part of the solution, not part of the problem. And we in the United Nations must step up our efforts to support the people of these countries as they build their own democratic future. Let me take the key arguments in turn.

First of all, there are those who say there has been too little progress, that the Arab Spring has produced few tangible improvements in people’s lives. This isn’t right. Look at Libya since the fall of Gaddafi. We have seen elections to create a new Congress.

And now plans to integrate armed groups into the national police and army. None of this is to ignore the huge and sobering challenges that remain. The murder of Ambassador Chris Stevens was a despicable act of terrorism. But the right response is to finish the work Chris Stevens gave his life to. And that’s what the vast majority of Libyans want too.

As we saw so inspiringly in Benghazi last weekend, they are taking to the streets in their thousands, refusing to allow extremists to hijack their chance for democracy. The Arab Spring has also brought progress in Egypt where the democratically elected President has asserted civilian control over the military, in Yemen and Tunisia where elections have also brought new governments to power and in Morocco where there’s a new constitution - and a Prime Minister appointed on the basis of a popular vote for the first time. And even further afield, Somalia has also taken a vital step forward by electing a new President.

So there has been progress. And none of it would have come about without people standing up last year and demanding change and this United Nations having the courage to respond.

Second, there is the argument that the removal of dictators has started to unleash a new wave of violence, extremism and instability. Some argue that in a volatile region only an authoritarian strong man can maintain stability and security. Or even that recent events prove that democracy in the Middle East brings terrorism not security and sectarian conflict not peace. Again I believe we should reject this argument.

I have no illusions about the danger that political transition can be exploited by violent extremists. I understand the importance of protecting people and defending national security.

And Britain is determined to work with our allies to do this. But democracy and open societies are not the problem.

The fact is that for decades, too many were prepared to tolerate dictators like Gaddafi and Assad on the basis that they would both keep their people safe at home .and promote stability in the region and the wider world. In fact, neither was true. Not only were these dictators repressing their people, ruling by control not by consent, plundering the national wealth and denying people their basic rights and freedoms, they were funding terrorism overseas as well.

Brutal dictatorship made the region more dangerous not less. More dangerous because these regimes dealt with frustration at home by whipping up anger against their neighbours, the West and Israel. And more dangerous too, because people denied a job and a voice were given no alternative but a dead end choice between dictatorship or extremism.

What was heartening about the events of Tahrir Square was that the Egyptian people found their voice and rejected this false choice. They withheld their consent from a government that had lost all legitimacy. And they chose instead the road to a more open and fair society. The road is not easy - but it is the right one and it can make countries safer in the end. Next, there are those who say that, whatever may have been achieved elsewhere, in Syria, the Arab Spring has unleashed a vortex of sectarian violence and hatred with the potential to destroy the region.

Syria does present profound challenges. But those who look at Syria today and blame the Arab Spring have got it the wrong way round. You can not blame the people for the behaviour of a brutal dictator. The responsibility lies with the brutal dictator himself. Assad is today inflaming Syria’s sectarian tensions, just as his father did as far back as the slaughter in Hama 30 years ago.

And not only in Syria. Assad has colluded with those in Iran who are set on dragging the region in to wider conflict. The only way out of Syria’s nightmare is to move forward towards political transition and not to give up the cause of freedom.The future for Syria is a future without Assad. It has to be based on mutual consent as was clearly agreed in Geneva in June.

But if anyone was in any doubt about the horrors that Assad has inflicted on his people, just look at the evidence published by Save the Children this week; schools used as torture centres, children as target practice. A 16 year old Syrian called Wael who was detained in a police station in Dera’a said: “I have seen children slaughtered. No, I do not think I will ever be ok again…If there was even 1% of humanity in the world, this would not happen”.

The blood of these young children is a terrible stain on the reputation of this United Nations. And in particular, a stain on those who have failed to stand up to these atrocities and in some cases aided and abetted Assad’s regime of terror. If the United Nations Charter is to have any value in the 21st Century we must now join together to support a rapid political transition. And at the same time no-one of conscience can turn a deaf ear to the voices of suffering. Security Council Members have a particular responsibility to support for the UN appeal for Syria.

Britain, already the third biggest donor, is today announcing a further $12 million in humanitarian support, including new support for UNICEF’s work helping Syrian children. And we look to our international partners to do more, as well.

Of course the Arab Spring hasn’t removed overnight the profound economic challenges these countries face. Too many countries face falling investment, rising food prices and bigger trade deficits. But it’s completely wrong to suggest the Arab Spring has created these economic problems. It’s a challenging time for the world economy as a whole. And there was never going to be an economic transformation overnight, not least because far from being successful, open, market-based economies, many of these countries were beset by vested interests and corruption, with unaccountable institutions. And this created a double problem.

Not just fragile economies, but worse, people were told they had experienced free enterprise and open markets - when they had experienced nothing of the sort.

We must help them unwind this legacy of endemic corruption, military expenditure they can’t afford, natural resources unfairly exploited - in short, mass kleptocracy that they suffered under for so long.

And while I’m on the subject of stolen assets, we also have a responsibility to help these countries get back the stolen assets that are rightfully theirs, just as we have returned billions of dollars of assets to Libya. It is simply not good enough that the Egyptian people continue to be denied these assets long after Mubarak has gone.

Today I am announcing a new British Task Force to work with the Egyptian government to gather evidence, trace assets, work to change EU law and pursue the legal cases that will return this stolen money to its rightful owners the Egyptian people.

Finally, and perhaps most challenging of all for Western countries like mine, is the argument that elections have simply opened the door to Islamist parties whose values are incompatible with truly open societies. My response to this is clear. We should respect the outcome of elections. But we should not compromise on our definition of what makes an open society. We should judge these Islamists by what they do. The test is this.

Will you entrust the rights of citizenship to your countrymen and women who do not share your specific political or religious views? Do you accept that - unlike the dictators you replaced - you should never pervert the democratic process to hold onto power if you lose the consent of the people you serve? Will you live up to your commitments to protect the rule of law for all citizens, to defend the rights of Christians and minorities and to allow women a full role in society, in the economy and in politics? Because the truth is this: you can not build strong economies, open societies and inclusive political systems if you lock out women. The eyes of the world may be on the Brothers, but the future is as much in the hands of their mothers, sisters and daughters.

Holding Islamists to account must also mean that if they attempt to undermine the stability of other countries or if they encourage terrorism instead of peace and conflict instead of partnership, then we will oppose them. That is why, Iran will continue to face the full force of sanctions and scrutiny from this United Nations until it gives up its ambitions to spread a nuclear shadow over the world. And it is also why we will not waver from our insistence that Hamas gives up violence. Hamas must not be allowed to dictate the way forward.

Palestinians should have the chance to fulfil the same aspirations for a job and a voice as others in region and we support their right to have a State and a home. And Israelis should be able to fulfil their own aspirations to live in peace and security with their neighbours.

So, of course there are challenges working with governments that have different views and cultural traditions. But there’s a fundamental difference between Islam and extremism.

Islam is a great religion observed peacefully and devoutly by over a billion people. Islamist extremism is a warped political ideology supported by a minority that seeks to hijack a great religion to gain respectability for its violent objectives. It’s vital that we make this distinction. In Turkey, we see a government with roots in Islamic values, but one with democratic politics, an open economy and a responsible attitude to supporting change in Libya, Syria and elsewhere in the region. I profoundly believe the same path is open to Egypt, Tunisia and their neighbours. And we must help them take it. Democracy and Islam can flourish alongside each other. So let us judge governments not by their religion - but by how they act and what they do. And let us engage with the new democratic governments in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya so that their success can strengthen democracy not undermine it.

Mr President, there is no doubt that we are in the midst of profound change and that many uncertainties lie ahead. But the building blocks of democracy, fair economies and open societies are part of the solution not part of the problem. Indeed, nothing in the last year has changed my fundamental conviction.

The Arab Spring represents a precious opportunity for people to realise their aspirations for a job, a voice and a stake in their own future.

And we, in this United Nations, must do everything we can to support them.