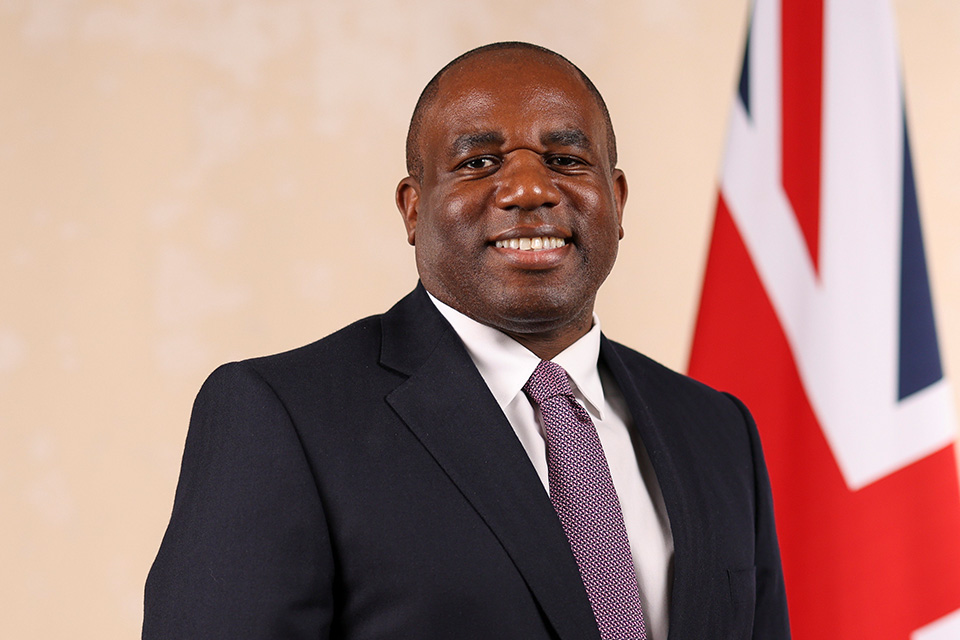

David Lammy's key note speech at the Lammy Review Trust in the CJS event

David Lammy’s key note speech at the Lammy Review Trust in the Criminal Justice System event.

Good morning and welcome to the Ministry of Justice.

I have to admit that as I watched the results come in on election night last year I did not expect to be making speeches from inside government buildings any time soon.

So you can imagine my curiosity in January when, as an Opposition backbencher, I received a cryptic message from Michael Gove, then the Justice Secretary, asking if we could meet privately.

As it turned out, the meeting was to sound me out, on behalf of the Prime Minister, about leading an independent review on race and the criminal justice system.

One of the many reasons that invitation took me by surprise is that this review is quite unusual.

Unlike other moments in our recent history, when race has been put under the spotlight, there was no single event that you could say triggered this review.

It was riots in Brixton that led to the Scarman report in 1991.

It was the murder of Stephen Lawrence that eventually produced the Macpherson report in 1999.

It was more riots in Bradford, Burnley and Oldham that led to the Cantle report in 2001.

Zahid Mubarek’s murder at at Feltham Young Offenders Institute led to the enquiry held in his name in 2006.

But this review is the result of something else: a fledgling political consensus in the UK that more must be done on race equality.

That’s how a Labour member of parliament ends up leading an independent review at the request of a Conservative Prime Minister.

And I think it is significant that the impetus for this review has survived not just a change of Ministers in this Department but also a change of Prime Minister.

One of the first things that Theresa May said on steps of Downing Street as Prime Minister was that “If you’re Black, you’re treated more harshly by the criminal justice system than if you’re White”.

One of the first things that she has done as Prime Minister is to begin an audit of whether ethnic minorities have equal access to public services.

Now I have been an MP for 16 years. I am not naïve enough to think that there will be no more political disagreements on race, or that all the battles have now been fought and won.

Martin Luther King said that “Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable… Every step toward the goal of justice requires sacrifice, suffering, and struggle”.

He was right, of course.

But I do think that we have an opportunity to take another step forward in Britain. That’s why I said yes to David Cameron and it is why I take what Theresa May says in good faith.

The Review

My Review, as many of you know, has been running since January this year.

It looks at why Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups are over-represented in our criminal justice system, and what can be done about it.

It addresses issues arising from the Crown Prosecution Service onwards, including the court system, prisons and young offender institutions and rehabilitation in the community.

From a race perspective, these are parts of the justice system that have been subject to much less scrutiny over the years than has been the case with the police.

So whilst this is not a year zero moment – because we stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before us – I do expect to break new ground in the evidence that we produce and the recommendations that I make.

Because this review has one big advantage: it is independent, but government sponsored.

That means we have access the vast store of data that the Criminal Justice System holds, but those outside the system often cannot access.

And it means we have the resources to analyse the data in new ways, bringing us closer to the truth about how the system works.

Trust

Today we are here to talk about how to build trust in the justice system among ethnic minority communities – and that subject provides a good example of what I am talking about.

One of the first things I did when the review was announced was to bring together leading academics to set out precisely what work had already been done and how best we could build on it.

In that discussion, one of them said something surprising.

On average, he said, ethnic minorities actually have higher trust in the Criminal Justice System than those from White backgrounds. You should consider what that means.

The facts are there in the Crime Survey for England and Wales, he said.

So we checked the figures and there it is:

64% of White respondents believe the Justice System is fair, compared with 71% of those from ethnic minority backgrounds.

This was unexpected, to say the least.

So we re-analysed the data to check we were not missing something.

And we found something important. Where you were born makes a big difference.

If you are born abroad but move to Britain then you tend to arrive in the UK with very high trust in its institutions.

94% of ethnic minorities who have recently arrived in the county say they believe the justice system is fair, for example.

As people live in the country for longer their trust in the system falls, whether they are White or from an ethnic minority background.

Among ethnic minorities who have lived in the country for more than five years, that 94% figure for recent arrivals has fallen to 77% saying they believe the system as a whole is fair.

And when you look just at those born in this country, you find that trust in the justice system tends to be lower for ethnic minorities than it is for the White population. So among those born in this country:

- 64% of White respondents say they ae confident that ‘the Criminal Justice System as a whole is fair’, compared with 60% from the ethnic minority backgrounds

- 35% of White respondents agree that ‘the Criminal Justice System discriminates against particular groups or individuals’, compared with 51% of those from ethnic minority backgrounds

- 74% of White respondents believe that ‘the Criminal Justice System treats those who have been accused of a crime as innocent until proven guilty’, compared with 70% of from ethnic minority backgrounds

On some measures ethnic minorities score higher – for example on whether punishments tend to fit the crime – but overall the trend is clear.

Now that isn’t just an academic exercise.

It tells us some important things.

It tell us that we have a better system than many, many countries around the world, where the rule of law is much weaker. That’s why new arrivals express such high levels of trust in it.

But it also says that we have problems. Trust falls away as people spend longer in the country. And when you compare like–for-like – those born in this country – ethnic minorities have lower faith in the fairness of the system.

Why trust matters

All this matters.

The first reason for that is that a lack of trust can be an sign of injustice.

That is why the government chooses to track confidence in the system.

And the evidence from my visits across England and Wales, supported by the survey analysis that I have just described, is that it is not just the Prime Minster who thinks that “If you’re Black, you’re treated more harshly by the criminal justice system than if you’re White”.

I have heard this story from offenders who feel they were treated differently because of the colour of their skin.

In this country 25% of the prison population and over 40% of the youth prison population come from ethnic minority backgrounds. That compares to 14% of the overall population.

I don’t believe all the causes of this lie in the criminal justice system, or that all the answers do either. But a deficit of trust set alongside an imbalance like that has to be taken very seriously indeed.

The second reason trust matters is that it can affect the decisions that individuals themselves take when they come into contact with the Criminal Justice System.

One of the most striking findings in the review is that defendants from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to plead ‘not guilty’ across almost every type of offence.

Some, of course, are not guilty.

But I have spoken to numerous prisoners who now admit to having committed the crime – yet for one reason or another pled ‘not-guilty’ anyway.

It can start with young men and women refusing to cooperate with the police and offering only ‘no comment’ in police stations.

This can be compounded by a lack of trust in the motives and competence of lawyers provided through legal aid. So legal advice can be refused or ignored by those who think their lawyer is simply part of ‘the system’.

It can mean defendants arriving in court with little prospect of an acquittal, but having spurned the chance for their sentence to be reduced by up to a third with an early guilty plea.

The result is wasted resources in the criminal justice system and many more years in prison for ethnic minority men and women than could have been the case.

One prisoner at Grendon prison in Buckinghamshire said to me that only now had he realised that the law is there to protect him against unfair treatment, not to catch him out.

When I talk about the importance of trust in the system I am thinking of people like him.

Third, there is a growing body of evidence to show the importance of trust in a successful prison system.

A pioneering study in Holland has tracked offenders during the course of their sentence and for 18 months after their release.

The results are significant.

Researchers found that when prisoners believed that they were being treated fairly, mental health was better, misconduct was lower and even reoffending rates were reduced.

As part of the study, prisoners were asked respond to a series of questions, producing a score of 0 to 5 on how fair they thought their treatment in prison was.

The difference between a score of 4 out of 5 and a score of 3 out of 5 was a 5.3 percentage point reduction in reoffending.

This evidence is compelling but the problem is that many of the ethnic minority prisoners that I have spoken to in this country do not have that sense that they are being treated like every other inmate.

Many complain that access to training and work experience on day-release is uneven, with assessments of risk bound up in racial stereo-types.

Others say that the earned privileges scheme, which rewards prisoners for good behaviour, can be arbitrary, opaque and even biased.

My team is examining the statistical evidence on these issues, amongst others.

But whether these complaints show up in the data or not, we have a problem if prisoners from ethnic minority backgrounds carry a sense of injustice as they serve their sentences.

Successful rehabilitation has to involve cooperation between prison officers and prisoners themselves. Without trust we won’t see that cooperation.

Today’s event

So trust matters.

It matters if it highlights injustice.

It matters if it affects the decision-making of offenders.

And it matters if it impacts on recidivism in the longer term.

That’s why we are holding the event today, as part of this wider review of race and the criminal justice system. Because we want to hear from you about where you think the problems lie and what you think the solutions are.

I know that many of you have already contributed to the review.

Over 300 individuals and organisations responded to the public call for evidence.

Each one of those submissions is being carefully read and analysed at the moment.

Others here have given up their time to meet me and members of my team to share their knowledge and ideas.

Some have gone further to host events and deliver research to inform our work.

- Catch 22 have hosted discussion groups with offenders at Thameside prison. We will hear more about that shortly

- BTEG are bringing together ex-offenders to share their experiences.

- Clinks have hosted consultation events in different parts of the country to bring together the views of voluntary sector organisations.

- Women in Prison and The Women and Girls Alliance have been analysing the challenges for female offenders from ethnic minority backgrounds.

- Friends, Families and Travellers have been hosting discussion groups with Gypsies and Travellers at HMP Coldingley.

I am incredibly grateful for all that – and I am asking for more from you today.

We need evidence, not just assertion.

We need solutions, not just problems.

Those are the things that will allow us to make the very best of this opportunity.

After this session we will break into smaller groups, to discuss everything from how the system works to who works in our criminal justice system – and how we get it looking more like the country it serves.

Members of my team will be with you taking notes.

And we will all come back together this afternoon to share the key points from each group.

So I hope you have a fruitful discussions and I will look forward to hearing what you have to say.