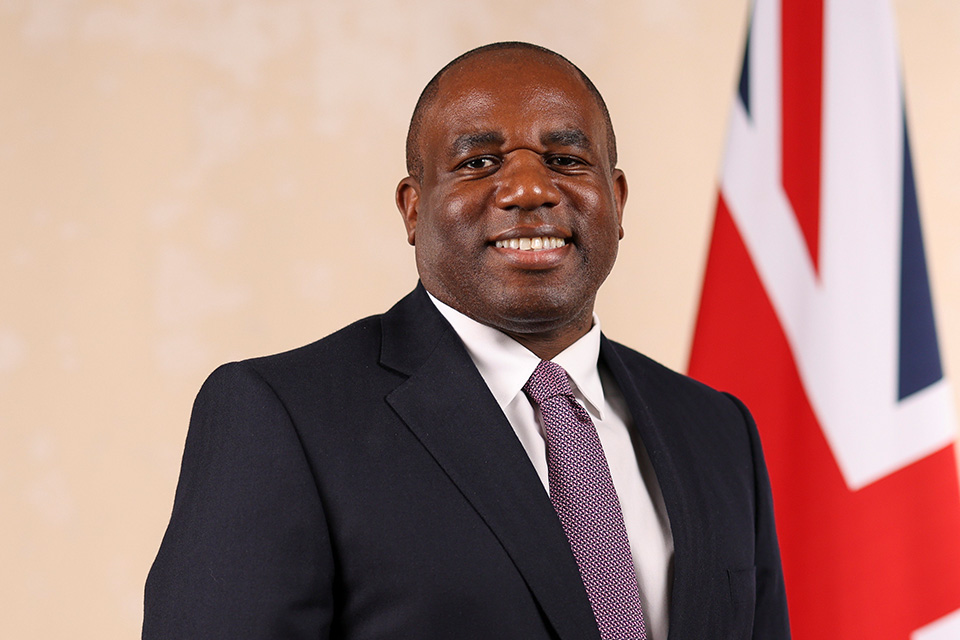

David Lammy’s speech to the National Police Conference

David Lammy’s speech to the National Police Conference

Thank you very much.

Today I release some of the emerging findings from my review of race and the Criminal Justice System.

So it is great to be here, with some of the key players represented.

This is a room full of experienced people – and you may have noticed something different about this review.

Typically, race reviews have been triggered by high profile events – a murder, a riot, a scandal within an institution.

That was the story of the Scarman report, the Macpherson report and the Cantle report.

This review is different because it emerges from something more gradual than that: a growing cross-party consensus.

A consensus that something must be done about the disproportionate representation of individuals from Black, Asian and Minority ethnic backgrounds in our criminal justice system.

- Ethnic minorities represent 25% of our prison population but just 13% of the country.

- 12% of prisoners are Black, compared with just 3% of the population.

- The number of Muslim prisoners has almost doubled in the last decade.

- Asians are over-represented. Gypsies and Travellers are over-represented.

- 4 in 10 of those in youth prisons are from minority backgrounds, up from less than 3 in 10 just a decade ago.

This is what led to a Conservative Prime Minister, David Cameron, asking me, a Labour backbencher, to carry out an independent review earlier this year.

And the concern is there across governments, not just across parties.

The new Prime Minister, Theresa May, raised the issue of racial equality of the steps of Downing Street on her first day in the job.

So in one sense this is an unusual review, but it also represents a rare opportunity.

Starting assumptions

I began work on the Review with a few starting assumptions.

The first is that I don’t believe that all the causes of over-representation lie in the criminal justice system – or that all the answers do either.

People end up in prison when they make bad choices.

But the people who make bad choices are often those who lack any real stake in society, from financial security to settled relationships in families and communities.

Our justice system can’t resolve all that on its own and we shouldn’t imagine that it can.

But what a Review like this can do is ensure that our system is scrupulously fair, that it does not waste a single penny by locking up those it should not, and that it does everything it can to help offenders turn their lives around.

So I am realistic about what is achievable through a review like this and what is not.

My second starting point was that we are not the only country that faces this challenge.

Cast your eye around the world and you find some equally stark figures.

- In America, one in 106 White men are incarcerated, compared with one in 15 African American men.

- In Canada, indigenous adults make up 3 percent of the population but 25 percent of the prison population.

- In Australia, Aboriginal prisoners make up 2 percent of the population but 28 percent of prisoners.

- In New Zealand a majority of those behind bars come from Maori backgrounds.

- In France, the estimate is that Muslims make up 8 percent of the population and 70 percent of prisoners.

So we are not alone.

I mention this not as cause for complacency, but because I am determined that this review will draw on the very best research, ideas and practice from around the world.

Third, for a review like this to be credible, it has to be both inclusive and evidence-based.

I know that this is an emotive subject.

It speaks to issues of personal and professional identity.

It concerns the treatment of individuals and the legitimacy of important public institutions.

I know that some minds are made up already – from those who believe the system is racist to others who don’t see any problem at all.

My position is that all those voices must be heard.

I have spoken to prisoners and prison officers, lawyers and judges, politicians and community groups, academics and campaigners.

I will continue to do that.

And I want to test what I hear against the best available evidence.

So, in addition to consulting widely, I have commissioned analysis that will break new ground in our understanding of race and the criminal justice system in this country.

Emerging findings

Today is the day I publish some of that analysis.

The work is peer-reviewed analysis, published as a stand-alone paper.

It is accompanied by an official statistics publication on race and sentencing.

In addition to those documents I am also publishing an open letter to the Prime Minister, setting out some of the areas I have concerns about – and the themes I intend to explore in more detail in the second half of this review.

My review focusses on issues arising from the involvement of the Crown Prosecution Service onwards, including the court system, prisons and young offender institutions and rehabilitation in the community.

But to put the rest of the system in context, we have also to understand arrest rates too.

So the analysis today finds that arrest rates are generally higher for ethnic minorities in comparison to the White population.

For example, Black boys were just under three times more likely than white boys to be arrested, while Black men were more than three times more likely to be arrested than White men.

That, of course, affects the number of defendants proceeding through the courts system and ultimately into prison if convicted and sentenced.

I don’t want to dwell on policing other than to say that it is impossible to conduct a review like this without receiving significant representation on Stop and Search in particular.

That is something the Prime Minister was right to address during her time as Home Secretary. It is something the new Home Secretary has commented on already.

And it is an issue the College of Policing continues to look at through its training regime, which now encompasses how to avoid bias in decision-making.

It is clear to me these changes are part of an important, ongoing reform agenda.

The rest of the criminal justice system presents a mixed picture.

There are some bright spots.

In the analysis, to date, the CPS comes out well.

There are not large disparities in charging decisions. The staff base of the organisation looks much like the rest of the country, with 16% of its employees coming from ethnic minority backgrounds.

The organisation also has a series of checks and balances to ensure charging decisions have proper oversight.

The picture looks positive for the jury system as a whole too. Again, there are not large disparities to report, reflecting similar findings from the excellent work of Professor Cheryl Thomas at University College London.

There are some anecdotal concerns about jury trials for minorities outside of metropolitan areas – certainly defendants report feeling on the back foot in those contexts. I will examine the evidence further to see if there is something in this.

There are, though, some findings from the work published today that do raise concerns.

Sentencing at crown court is one of those areas.

The analytical paper published today shows, for example, that of those convicted at Crown court, 112 Black men were sentenced to custody for every 100 White men.

The equivalent figure is 125 Black women sentenced to custody for every 100 White women.

When more fine-grained analysis is done, controlling for offence group, age, gender, plea decision and offending history there are still disparities – with ethnic minority defendants more likely to receive prison sentences.

This is, of course, something I intend to look at very closely in the coming months.

Prisons are another area where the analysis throws up some things to worry about.

It finds that Black men are more likely than White men to be placed in high security prisons for some categories of offence.

This can restrict access to opportunities like work experience on day release, which can be vital for rehabilitation.

It is also the case that Black prisoners are more likely to face adjudications for misconduct but less likely to see those adjudications upheld when they are reviewed.

The great danger is that this breeds a culture of ‘them and us’ – a culture not helped, I must say, by the lack of diversity in prison staff – which all the evidence suggests can contribute to disorder in prisons and hamper rehabilitation.

The probation system, as people here are aware, has been through a period of quite significant change. I am looking closely at the impact of that but it is important also to mention our criminal records regime at this point.

It is an issue I have had significant representation on – with many describing it as a ‘second sentence’, locking people out of the labour market even if they are no longer locked up in prison.

The danger is that we entrench patterns of disproportionality by making it hard for the ex-offenders to break the cycle. I will be looking further at that issue, with a particular eye on the under 18s.

Key themes

So there are some parts of the Criminal Justice System that the review will need to look more closely at in its second phase, between now and the middle of next year when the final publication is due.

But there are also some cross-cutting themes I want to mention briefly today.

The first of those is the question of data.

I think it is to the Government’s credit that this review is taking place. But in the future I want others, outside of government circles, to be able to scrutinise the data that I have been given access to.

I also want to be sure that when data is held on individuals it is both accurate and used in the appropriate way.

People in this audience may be aware that I have concerns about the Gangs Matrix, for example, as I have indicted in previous speeches. In London that database contains more than 3,500 names and almost 9 in 10 of those are from ethnic minority backgrounds.

There is also something important about new technology and the use of data in the future.

It is clear that ‘Big Data’ is making its way into criminal justice systems around the world, with statistical analysis used to make risk assessments about individuals.

That approach may well be an opportunity to screen out human biases and make more accurate assessments, but there are risks too.

We need to be clear what data is permissible to use. For example, should someone’s postcode, or their parents’ offending history, count against them even if it makes the model more accurate?

The risk of those things entrenching disproportionate representation is obvious.

These are not hypothetical questions. There are live debates over the use of such models in the United States. We need to be ready with answers to those questions here in the UK.

The second theme is oversight.

Today is about presenting findings rather than conclusions from this review.

But I will offer a hypothesis.

Those parts of the justice system that seem to be working well look to be those where decision-makers can be held accountable.

Members of juries must justify their opinions to others, for example,

The CPS, meanwhile, systematically reviews charging decisions to ensure rigour and balance.

Each prosecutor will have at least one randomly selected case reviewed each month. If a particular issue is identified then the level of scrutiny increases, both of that prosecutor and of decisions concerning that offence. This culture of peer review is common in other public services, from lesson observations in schools to multi-disciplinary case reviews in medicine.

It may well be something that other institutions in the criminal justice system could learn from.

The third theme is trust.

This matters immensely in tangible and intangible ways.

On a practical level, it is a concern that ethnic minority defendants are more likely, across offence types, to plead not guilty when charged.

This means individuals face longer sentences if found guilty.

It can start with the ‘no comment’ interview in the police station, continue with mistrust of the duty solicitor and culminate in a sense of grievance when people receive lengthy sentences in court.

That costs money and, of course, impacts on disproportionate representation.

But there are intangible issues too.

When 51% percent of ethnic minorities born in this country agree with the statement that ‘the Criminal Justice System discriminates against particular groups or individuals’ we have a problem.

We must have respect for the rule of law in this country.

This requires the key institutions in the justice system to command not just legal power but also public legitimacy. So I will be looking at how we build trust in those institutions.

One aspect of that must be diversifying professions like the judiciary, so that we break down this perception of ‘us and them’ that I have heard so often during the review.

The fourth theme is vulnerable groups.

It is well established that there are a series of vulnerable groups who are at risk of entering the justice system. I am talking, for example, about children from the care system and individuals with learning difficulties or mental health conditions.

Analysis for this review indicates that ethnic minorities may be over-represented within some of those groups themselves.

This may well be linked to income and for that reason is likely to be an issue for White working class communities too.

I will be looking at how the criminal justice system is set up to deal with these vulnerable groups. Getting this right could reduce racial disparities whilst benefitting other groups too.

The final theme I want to mention is the role that those beyond government can play in reducing racial disparities, principally by reducing reoffending rates.

Here I am thinking not only of those institutions with a formal role, such as the many employers and charitable organisations who do great work with offenders and ex-offenders.

I am also thinking of family members and local communities too.

I mentioned earlier my determination to draw on the best practice in this country and from around the world.

I am very interested in the ways some jurisdictions are working to build closer relationships between courts and communities.

That ranges from well-known initiatives like the Red Hook Community Justice Centre in New York to innovations I have seen in New Zealand and Australia which seek to draw communities into the court room to encourage, support and challenge offenders.

In this country I know the police have made significant efforts to builder closer relationships with local communities in recent years. The question I want to ask is what the equivalent steps are for other parts of our justice system.

Conclusion

That, I hope, gives a sense of my thinking at this stage in my review.

It is not a comprehensive list – there is more analysis to be done and I will continue to consult on these and other issues right up until the moment the ink dries on the final report.

But I do think it is important to give people some sense of direction at this half way point.

I am very grateful for the opportunity to do that in a little detail today – and wish you luck with the rest of the conference.

Thank you.