Iain Walker recounts experience with the Duke of Edinburgh's International award

The British High Commissioner to Ghana authored an op-ed on his experience with the Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award.

This week, Accra hosts the Global Forum for the Duke of Edinburgh International Award scheme (known in Ghana as the “Head of State Awards”). Celebrating its 30th anniversary, it is the first time this Forum has ever been held in Accra. The Earl of Wessex, who has taken over the Chairmanship from his father the Duke of Edinburgh, is actively shaping this body’s global ambition.

I am particularly pleased that Accra is hosting this important gathering. For me, the Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme was a formative experience.

At my school, the Award was run by a teacher called Mr Stibbles. During our Bronze Award we all found him fearsome, but by the time we had earned our Gold, he was – and still is – our favourite teacher. He, along with other teachers and volunteers, invested so much in us we will forever be in their debt. He has inspired many of us to share similar opportunities with young people today.

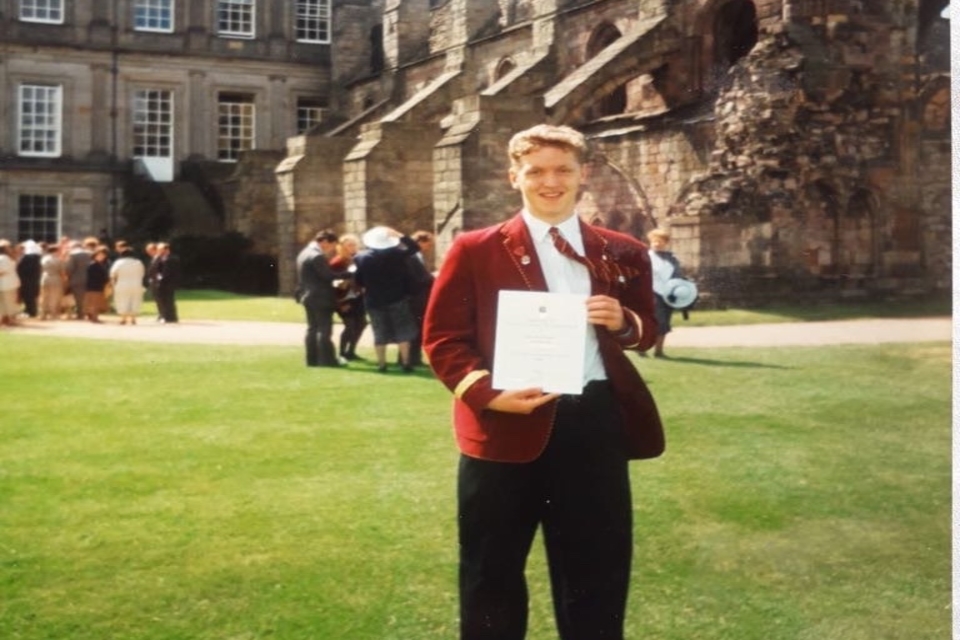

A young Mr. Walker back in school with his Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award mates

I loved doing the Duke of Edinburgh Award when I was at school. It encouraged me to try new things and to help other people. It gave me a taste of freedom and adventure. It showed me the importance – the sense of accomplishment - of seeing something through.

The award takes 3 years: first the Bronze Award, then the Silver and then – finally, if you make it that far – the Gold. Each level becomes a little more demanding. Each level is a little more fun:

- To meet the criteria for the “physical” component, I trained and qualified as a lifeguard. Years later - during a summer break from University– this skill took me to a US summer camp for underprivileged children in upstate New York, where I taught children to swim.

- To meet the requirement for “volunteering”, I helped teach at my local church Sunday school. I found it terrifying at first. Although it seemed insignificant at that moment in time, it helped develop my confidence in talking to others. And it showed me the importance of communicating clearly.

- For the “skills” component, I focussed on learning to play the clarinet. In truth, I often wanted to quit to go and play sport. But I stuck with it – I needed to demonstrate commitment - and went on to play in various local and regional orchestras.

Best of all, each level of the Bronze, Silver and Gold award culminates in an “expedition” where – as a team – you plan and then undertake a training and then assessment hike (with backpack, map, compass, tent). For me, that was undertaken in the Scottish Highlands. It was exhilarating, exhausting and extremely good fun.

I wasn’t particularly brilliant at any of the examples I’ve highlighted above. But in later life, I’ve found them all to be helpful in their own way. The importance of making a plan, and tenaciously seeing it through, is a discipline I’ve found important throughout my life. More than that, I made real friends as I did my Duke of Edinburgh award Scheme. Many of those people remain my closest friends to this.

And even more than that, the Head of State Awards remind me of the importance of community. Of how, as a young person, I benefitted from the investment of others in my development. And how, in a world of many competing priorities, making personal time to invest in the youth is more important now than it has ever been before.

I truly hope this Global Forum continues to grow the Award, so that it can generate opportunities and empower more young people to harness their potential.