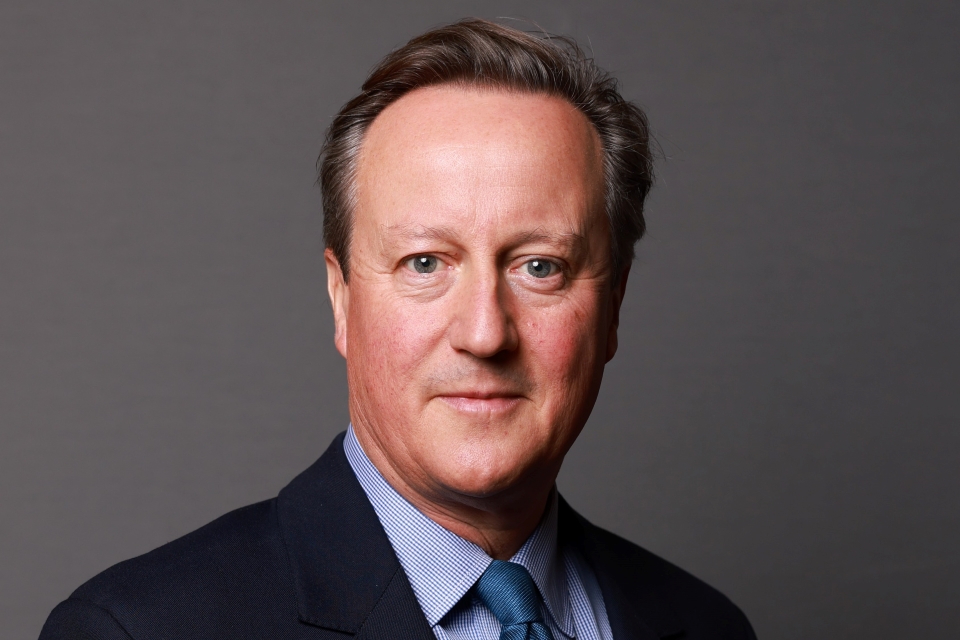

Economy speech delivered by David Cameron

David Cameron speaks about the economic situation and the plans to fix the fundamental problems in the economy.

Well, thank you very much for that introduction and welcome everyone. And can I say what a pleasure it is to be here, and what a pleasure it is to be here in a business like this because this is exactly the sort of business Britain needs more of: making more things, designing more things, inventing more things, exporting more things and recognising that engineering, manufacturing are an important part a vital part of Britain’s economic future.

And today I want to talk very plainly and clearly about our economic situation. I know that things are tough right now. Families are struggling with bills at the end of the month; some are just a pay check away from going into the red. Parents are worried about what the future holds for their children, and whole towns are wondering about where their economic future really lies. And I know that’s particularly true of people here in Yorkshire and in many parts of the north of our country, people who didn’t benefit properly from the so-called ‘boom’ years and who worry that they won’t do so again.

But I’m here today to say that is not going to happen because we have a plan to get through these difficulties and to get through them together. It is a plan to fix the fundamental problems in our economy, to get the jobs and the growth that can make our country a success in the global race, and to back the aspirations of hard-working families who want to get on in life. And my argument today is simple: if we stick to the plan and if we reject the false choices, we can come through this together with a stronger, more resilient and more balanced economy.

But first we’ve got to start with what went wrong because if we don’t understand what went wrong in our economy, we’ll never understand what is truly needed to put it right. Now our economy has been beset by three fundamental problems: the biggest budget deficit in post-war history; a build-up of private debt, accompanied by a global banking crash; and third, an erosion of our competitiveness in an era when global competition and the global race for our economic future has rapidly accelerated.

Now, I want to take each in turn. First, the deficit. Now this deficit didn’t suddenly appear purely as a result of the global financial crisis. It was driven by persistent, reckless and completely unaffordable government spending and borrowing over many years. By 2008, we already had a structural deficit of more than 7%, the biggest of any G7 country. And in the cold reality of the bust that followed, we saw the true scale of the myth of the boom that had preceded it. We saw the broken model of growth that was propelling our economy into an increasingly unsustainable position. We will not be able to build a sustainable recovery with long-term growth, unless we fix this fundamental problem of excessive government spending and borrowing that undermines our whole economy.

Now, second, we had over-indebted households borrowing from over-indebted banks. Banks lent more than they could afford to, spurred on by an irresponsible banking culture that rewarded short-termism and unmanageable risk-taking. And households borrowed more than they could afford to, spurred on by an assertion that we had, somehow, ended boom and bust. So when the crash came, we in Britain did not just have over-indebted banks, over-indebted households and a big budget deficit, we had the most over-indebted banks, the most over-indebted households as well as the biggest budget deficit of virtually any country anywhere in the world.

Now, third, there was this fundamental erosion of our competitiveness. Let me put this simply: Britain is in a global race. There’s a fierce battle for our economic future with great shifts in wealth taking place from West to East. And yet while this race was speeding up, under the last government we fatally undermined our competitiveness with layers of red tape and bureaucracy: £77 million of red tape with over 36,000 new regulations, more than 12 for every working day of that last decade. Our corporate tax regime went from being the 11th most competitive in the world to the 23rd most competitive. And the UK fell out of the top ten places for the ease of starting a business, meaning it took twice as long to start a new business here in the UK as it did in America, almost twice as long as in France and the same length of time as it does in Mongolia. Innovation was stifled and the ability of British business to compete internationally was seriously damaged. We fell from ninth in the global competitiveness league to thirteenth.

And the growth achieved in these years of the so-called ‘boom’ was far too dependent on unsustainable factors: excessive government spending, housing boom and uncontrolled immigration. None of these is a sustainable way to deliver long-term economic growth. When you look now at the reality of what happened in these years, you can see the true picture. Even at the end of the so-called ‘boom’, there were five million people in our country of working age on out of work benefits.

One fact I think tells the story of just how unbalanced the growth was. And that is the stunning fact that in the West Midlands, traditionally one of the engine rooms of our private sector economy, between 1999 and 2008, the number of people in private sector jobs not just manufacturing but in private sector jobs in that region of the country, an engine room of the economy, the number of people in private sector jobs actually fell.

The competitiveness problems in our country go very deep. The welfare system has failed to incentivise people to work. And our schools, in the past, have badly let down too many of our children. Approaching half of all 16 year olds in 2010 failed to get GCSE at Grade C or better in both English and Maths. We can argue forever about the importance of vocational education and I will have a lot more to say about that next week but there is not a job in the world that doesn’t need competent English and competent Maths. You’ve got to get that right. And we were left, as well, with over five million functionally illiterate adults.

Our plan to fix our broken economy takes each of these three problems head on. First, we have a clear plan to deal with the deficit. And it is fair. The richest 20% are making the greatest contribution to the deficit reduction and paying the most. And in every single year of this Parliament, the richest - the top 1% - will pay a greater share of our nation’s tax revenues than in any one of the thirteen years that preceded this government.

As important as it being fair, our plan is also pro-growth. In spite of making difficult cuts, we are protecting the science budget. We are protecting the money that flows to our schools. We are avoiding big increases in the taxes people pay on the money they earn. And we’ve actually added to the plans that we inherited for investment for vital infrastructure. For example, in spite of all that we are having to do to deal with the deficit, we have invested more in major road schemes in each of the last two years than in any year of the last Parliament.

We are making big cuts in bureaucracy, including by reducing the size of government. We now have the smallest civil service in Britain since the war. Some government departments are being cut in half. And we have already reduced the deficit by a quarter. We’ve cut the structural deficit that’s the bit of the deficit that doesn’t go away even after the growth has returned we’ve cut that by 3 percentage points. That is more than any other G7 country. And in contrast to some other major economies that, like us, are battling against big deficits, we’ve been able to pass the necessary legislation through Parliament. So, markets can be confident that we are implementing our plan and we will stick to our plan.

And dealing with the deficit gives us the credibility in world markets to maintain low interest rates. And it is, I think, hard to overstate the fundamental importance of low interest rates for an economy as indebted as ours, and also hard to underestimate the unthinkable damage that a sharp rise in interest rates would cause. When you’ve got a mountain of private sector debt, built up during the boom, low interest rates mean indebted businesses and families don’t have to spend every spare pound just paying their interest bills. In this way, low interest rates mean more money to spare to invest for the future. A sharp rise in interest rates as has happened in other countries which have lost the world’s confidence would put all of this at risk, with more businesses going bust and more families losing their homes. By sticking to our deficit reduction plans we can keep interest rates low.

Second, with the banking system badly damaged, it is absolutely vital to recognise that you need more than just fiscal responsibility, more than just a tough approach on the deficit, to turn low interest rates into the affordable loans essential for businesses and the low mortgage rates which keep the cost of living down and enable young people to be able to get on the property ladder for the first time. Why? Well, because when you’ve had such a catastrophic collapse in the banking system, as we experienced here in the UK, the mechanisms which provide this transition from low interest rates on paper to real low interest rates that businesses and households can access, the mechanisms for this transition are badly damaged. So we’re sorting out the financial system, we’re reforming our banks so they serve the economy, and we’re supporting this damage transition mechanism.

Now, we’ve already made some big strides in reforming the banking system and 2013 is the year when we’ll deliver much of this vital work. For the first time, it is clear where responsibility lies. No more of the so-called tripartite; it’s the Bank of England that has to support the recovery, without putting financial stability at risk. We’re creating a new law to separate the branch on the high street from the dealing floor in the city, so we protect tax payers where mistakes are made. And we should be clear about what this means.

In future, we’ll be able to sort out failing banks without asking taxpayers to put their money in. We’re also introducing more competition and choice into banking, so people and businesses have more choice about who they bank with, more choice to change their bank if they want a better deal. And we’re supporting these reforms with what I call monetary activism, supporting this damaged banking system that would otherwise struggle and still does struggle, in too many cases to pass on low interest rates.

Now this is inextricably linked to our fiscal credibility, because the low interest rates on our debt gives us gives the government the capacity to use our balance sheet to pass on those low rates through to families and through to businesses. And we’ve been incredibly active in doing this. The Bank of England introduced a funding for lending scheme, which is now being copied around the world. We’ve introduced a new-buy scheme that helps people who only have access to small deposits to buy a newly built home.

And the treasury has, for the first time historically, offered guarantees, Treasury guarantees, for housing and infrastructure investments, using the strength of its balance sheet to kick-start investment throughout the economy.

Now these initiatives, I think, really matter. Take mortgages, for instance. Of course we don’t want to go back to the days of the 110% mortgage, when we encouraged people to take on borrowing they can’t afford, but it is important that people who work hard and do the right thing are able to buy a home of their own. And as I said in my party conference speech, it is a rebuke to those of us who really believe in a property-owning democracy that the average age for someone buying their first home today, without any help from their parents, the average age is 33 years old.

Now I am determined that we are going to tackle that. Now, with the help of funding for lending, the cost of a two-year, fixed rate, 100,000 mortgage, with a 10% deposit, that is now £1,000 cheaper than when the scheme was launched. It’s now possible to buy a new home, anywhere in the country, with only a 5% deposit and at very low interest rates. That is vital.

Housing isn’t all of our economy; it’s not the only vital sector, but if you want to see a strong and good and sustainable recovery, you need a functioning working housing market. And that is what these changes, I believe, will help to deliver. As a result, the Council of Mortgage Lenders forecast that mortgage lending will actually rise this year by £10 billion; that will be the first rise since the financial crisis. As we look ahead to the budget, we’ll consider where there’s more we can do to build on this area of success.

But third, as I said, we are restoring our competiveness. At the forefront of this is our bold plan to cut corporation tax to 21%. That will be the lowest in the G7. As the recent KPMG survey shows, in just over two years we’ve transformed business perceptions of our corporate tax system from one of the least competitive to one of the most competitive in the world. We’re introducing some of the most generous tax breaks for early investment start-ups of any developed economy on the planet. And, by stripping back the red tape that was smothering businesses, we’ve put Britain back in the World Economic Forum’s Top Ten for competitiveness.

We’re getting behind British business, helping to win contracts in tough overseas markets by breaking down barriers to trade, including with today’s new export action plan for the retail sector, which is assisting up to 1,000 companies, including 600 SMEs, to deliver £0.5 billion of new business for Britain over the next two years. And we are getting behind the industries of the future.

This Government is not laissez-faire, but neither is it about picking winners or keeping dead companies on life support, like the failed industrial policies of the 1970s. It is about backing the industrial sectors where Britain has comparative global advantage. Sectors like aerospace, where we are the number one manufacturing sector in Europe, or our automotive industry, which had a trade surplus in 2011 for the first time in nearly 40 years. It is important to sort of stop and think about that. Think of our car industry and think of the decline of our car industry. In 2011, we sold more cars overseas than we imported into the UK. That is something I believe we can be proud of, and we can build on.

Just this morning in Downing Street, I met with leading managers of Global Investment funds, worth many billions of pounds, who are looking at investing in our very exciting, very innovative energy sector. In life sciences, and in other industries, our patent box which is effectively a 10% tax on profits for firms who turn innovation in the UK to manufacturing in the UK is driving millions of pounds of new private sector investment into, example, our world-leading pharmaceutical centre.

But I know this business right here, which is a great innovator, a great inventor, a great creator of IP, is looking at using that patent box, because you’re developing ideas here, you’re manufacturing ideas here, so you should be able to benefit from that 10% rate as well.

We’re also supporting start-ups, making it easier for insurgent companies from across Europe to float on the London Stock Exchange. We’re helping technology clusters, like Tech City in London, which is rapidly becoming one of the fastest growing technology clusters anywhere in the world.

But competitiveness goes much wider than that. So we’re reforming welfare and education, so it pays to work and people have the skills to do so, including new changes being announced today to improve the quality and rigour of vocational education for 16 to 19 year olds. And in the weeks ahead I’ll be talking more about the wider changes we’ll be making to vocational education, as well as apprenticeships, so that we back all of those who want to get on and succeed in life.

Now, some people think that talking about making our economy more competitive is a sort of motherhood and apple pie agenda. It absolutely isn’t. Some of the changes we need to be competitive will be a big fight: housing reform, planning reform, the building of new roads, new bypasses, High Speed Rail. These are fundamental changes; they’re essential for the future of our economy, but they are not and I don’t expect them to be universally supported.

But my message is simple, people should make no mistake, in this battle for the future of Britain and our competitiveness, I’m prepared to roll-up my sleeves and have a fight, if that’s what it takes. So that is our plan: fiscal responsibility, monetary activism and restoring our competitiveness to succeed in the global race.

Now, of course, there are plenty of people out there with different advice about how to fix our broken economy. Some say cut more and borrow less, others say cut less and borrow more; ‘go faster’, ‘go slower’, ‘cut taxes’, ‘put them up’. I think we need to cut through all of this and tell people some pretty plain truths.

So let me speak frankly and do just that. There are some people who think we don’t have to take all these tough difficult decisions to deal with out debts; they say that our focus on deficit reduction is damaging growth and that what we need to do is to spend more and to borrow more. It’s as if they think there is some magic money tree, and let me tell you a plain truth: there isn’t.

Last month’s downgrade, by one of the ratings agency, was the starkest possible reminder of the debt problem that we face. And if we don’t deal with it, interest rates will rise, homes will be repossessed, businesses will go bust, and more and more taxpayers’ money will actually be spent just paying off the interest on our debts. Even a 1% rise in mortgage rates would cost the average family £1,000 in extra debt service payments.

So there is not some choice between dealing with our debts on the one hand, and planning for growth on the other. As the Independent Office for Budget Responsibility has made clear, growth has been depressed by the financial crisis, by the problems in the eurozone and by a 60% rise in oil prices between August 2010 and April 2011. They are absolutely clear, and they are absolutely independent. They are absolutely clear that the deficit reduction plan is not responsible; in fact, quite the opposite. Tackling the deficit is the first essential step for growth and, if we don’t do it, we’ll end up facing even greater austerity.

The Moody’s rating agency, the one that downgraded us, they said that the UK’s credit worthiness remains extremely high; they said this was thanks in part to a strong track record of dealing with our debts and, and I quote, ‘political will’. They make it absolutely clear that they could downgrade the UK’s credit further in event of, and I quote, ‘reduced political commitment to fiscal consolidation’.

So those who think we can afford to slow down the rate of fiscal consolidation by borrowing and spending more are jeopardizing the nation’s finances and they’re putting at risk the livelihoods of families and businesses up and down the country.

[Political content.]

And at the same time as dealing with our debts, we also want to help hardworking families cope with the cost of living. Now that is why, for instance, we’re legislating to insist that families are automatically put on the lowest variable tariff for their electricity and gas bills. We’re cutting the cost of motor insurance by clamping down on some of the, frankly, completely unacceptable practices that have been pursued by some in the legal industry. And, of course, one of the best ways to help hardworking families is to cut their taxes. And as a low-tax conservative, I absolutely believe in doing this. It is, of course, what we’ve done by cutting fuel duty and by freezing the council tax. And from this April, we are delivering the biggest ever increase in the income tax threshold the amount of money that you can earn before you start paying income tax. This move will lift over two million people out of tax altogether since 2010, and effectively half the amount paid by someone working full time on the minimum wage a really important point there. Someone on the minimum wage working a full working week, their income tax bill would have been cut in half since this government came to office.

Now, of course, there is a case for going even further and making even more tax cuts. But the key point is this: you have to be able to fund them. Now, of course, there are times when you can cut a tax and find it almost pays for itself. That was the view of the Independent Office for Budget Responsibility when it came to the 50p income tax rate, which is why we’re getting rid of it. But most of the time, tax cuts don’t completely pay for themselves. Margaret Thatcher understood that a tax cut paid for by borrowed money is really no tax cut at all when she said, ‘I’ve not been prepared ever to go on with tax reductions if it meant unsound finance.’ So, yes, we’re doing a great deal to help hardworking families, but all of these changes have to be paid for and they have been paid for.

Getting taxes down to help hardworking people can only be done by taking tough decisions on spending and that is what we’re doing in our plan. And this month’s budget will be about sticking to the course because there is no alternative that will secure our country’s future.

Now, of course, the challenges are huge and there is, I completely accept, a long way to go. But I believe already there are signs that our plan is beginning to work. The biggest deficit in peace time history, as I’ve said, is already down by a quarter. Interest rates, as I’ve said, are at near record lows. Exports are starting to turn around too. Over the past three years our exported goods to the fastest growing parts of the world have been soaring Brazil, up by half; India, more than half; China, almost doubled; Russia, up by 133%, and I’m proud to say this factory I’m standing in has been contributing to almost all of those statistics.

And these aren’t just statistics. These increases in British exports mean British businesses getting new orders and that means jobs right here back at home. The number of people on out-of-work benefits has fallen and there are one million extra private-sector jobs over the last two and a half years. There are also more people in work than ever before in our history. And today, we welcome the news from British Telecom, from BT, that they’re creating another thousand new jobs, including 400 apprenticeships, as part of their £2.5 billion investment in broadband where Britain has the fastest broadband roll-out scheme anywhere in the developed world.

Now, most importantly of all, our economy which was previously so badly unbalanced now has private-sector employment levels rising in every part of the country and they are rising fastest right here in the North of England. Within one year of this government, we had a faster rate of new business creation than at any time in our history. Today we have more than a quarter of a million new private-sector businesses, the biggest increase in private enterprises on record with more than three quarters of these new businesses created outside London. It is a new generated private sector that we need for our country.

Now, of course, these signs of progress are just the beginning of a long, hard road to a better Britain. But the very moment when we’re just getting some of those signs that we can turn our economy around and make our country a success is the very moment to hold fast to the path that we have set. And, yes, the path ahead is tough, but be in no doubt; the decision we make now will set the course of our economic future for years to come. And while some would falter and plunge us back into the abyss, we will stick to the course.

Now, I know some people think, it is somehow stubborn to stick to a plan, but somehow this is just about making numbers add up without a care, without a proper care for what it means to people affected by the changes we make. As far as I’m concerned, nothing could be further from the truth. My motives, my beliefs, my passion for sticking to this plan are exactly about doing the right thing to help families and to help businesses up and down our country, because the truth is this: because if we want good jobs for our children, we will not get them if we are burdened with debt and outcompeted by India and China. If we want and I do want good public services, we won’t be able to afford them if our economy is weak and we’re spending half of the budget on debt interest. If we want and I passionately want to be able to look after people with dignity in their old age, we won’t be able to do that if we are still squandering billions of pounds on welfare for people who could work but don’t. If we want to help people into work, if we want to break the cycle of poverty that affects too many families in country in our country, we’ve seen that ever-increasing working age welfare is not the answer. If we want to help with the cost of living, and I want to help with the cost living, that means cutting spending to keep taxes down.

So, yes, we are making tough choices about our future but we are making the right choices. If there was another way, some easier way, I would take it, but there is no alternative. The only way we’ll fix our broken economy and compete successfully in the global race is by fixing ourselves to a clear plan and sticking to it. And that is what we’re doing.

When I stood on the steps of Downing Street for the very first time, I said I believe the best days for Britain lie ahead of us, not behind us. I still believe that. And by sticking to the plan, we can prove it to be true. By sticking to the plan, we can together make Britain a great success story in this vital global race. Thank you.