Foreign Secretary sets out his vision to improve media freedom around the world

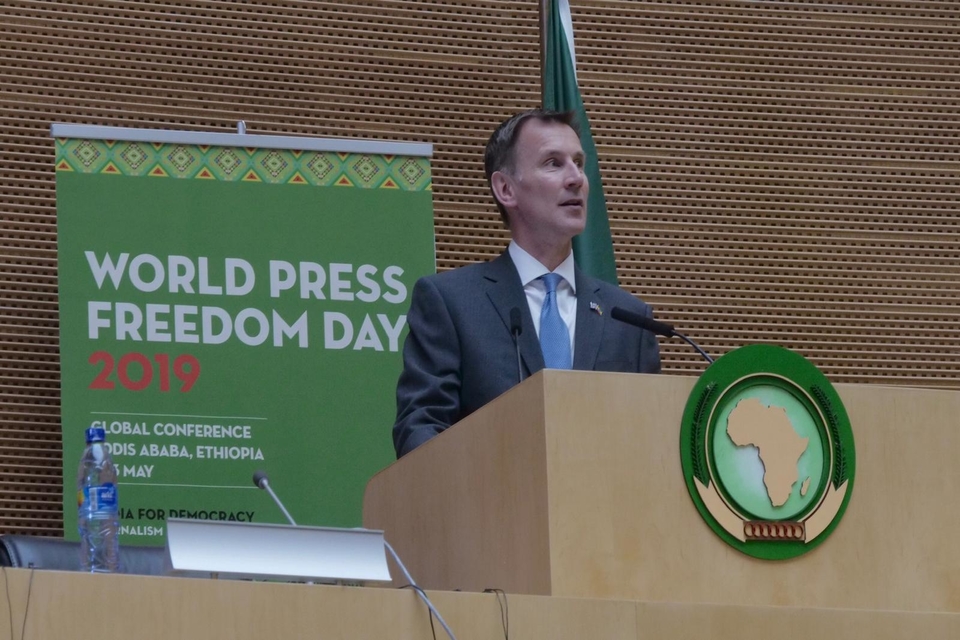

Speaking at the UNESCO World Press Freedom Day event hosted by the African Union in Addis Ababa, Jeremy Hunt set out his vision to improve media freedom.

I’m delighted to be in Ethiopia, where under Prime Minister Abiy’s leadership the new government has transformed political discourse by allowing the creation of hundreds of websites, blogs and newspapers.

Since the Prime Minister assumed office last year, Ethiopia has climbed the World Press Freedom Index faster than any other country, rising 40 places and showing just how much can be achieved when the political will exists.

In a world where 99 journalists were killed last year – and another 348 locked up by governments – some of the brightest spots are perhaps where some would least expect: right here in Africa. Gambia, for example, has climbed 30 places in the Index. Namibia has moved up again to keep its place as the country with the freest media in Africa.

So as we mark World Press Freedom Day, I want to start by celebrating the best of African journalism.

Whether it is the courageous investigations of Anas Aremeyaw Anas, who I was privileged to meet in Ghana, or Patrick Gathara’s insights into Kenyan politics, Charles Onyango-Obbo’s incisive commentary on Uganda, or the cartoons of Gado in East Africa and Zapiro in South Africa which show that a skilful caricature is worth a thousand words.

Whether it is the editors who bring out independent newspapers against the odds; the journalists who brave threats and intimidation; or the bloggers who keep a vigilant eye on their leaders; all know better than anyone that a lively and free media provides the best possible safeguard against corruption and misrule.

I congratulate BBC Africa for their investigation in Cameroon last year, which established that the army murdered 2 women and 2 children in a massacre in 2015 that was repeatedly denied by the authorities. As a result, soldiers have been arrested and face justice.

And I pay tribute to the memory of Mohammed Amin, the Kenyan photojournalist, who strove to make the suffering of Ethiopians in the 1980s known to the world.

A force for progress

Today, my argument is simple: media freedom is not a ‘Western’ value, still less a colonial-style imposition, but instead a force for progress from which everyone benefits.

The Indian Nobel Laureate, Amartya Sen, defined the “expansion of freedom” as what he called the “pre-eminent objective” of development. Far from being in tension, he showed that freedom and development were one and the same, and a flourishing media should be seen as part of the broader progress of a nation.

Whatever we politicians claim during election campaigns, no single party or leader or philosophy has a monopoly on wisdom. Instead the progress of humanity clearly shows that wisdom arises from the open competition between ideas when different viewpoints are given the oxygen to contend freely and fairly.

And by testing those ideas – including questioning authority – ordinary citizens achieve something else too: the precious dignity of being able to decide for themselves what they believe about their country’s future and then make informed decisions as to who their leaders should be.

When everyone is able to exchange ideas freely, a society benefits not just from the brains of the people at the top, but from the originality and creativity of the entire population.

That’s why half of the ten most inventive countries, as ranked by the Global Innovation Index, are also in the top 10 for media freedom. That’s also why, however fashionable it may be becoming in some countries, the authoritarian model of development is ultimately flawed.

Because even if you reject the dignity of the human spirit as an end in itself and believe the only priority for a poor nation should be economic progress – that progress itself requires innovation, which in turn needs creativity, itself also requiring openness.

So the argument that a free press is a ‘luxury’ which developing countries might ‘embrace when they are ready’ fundamentally misunderstands the role it plays. A free press is quite simply the first secure basis for prosperity in a world where innovation and technological advance are the central conditions for progress.

By their courage and determination, the people of Sudan have won the chance to reject the authoritarian model and achieve the democracy that is their right. No-one should stand in their way as they make this journey.

But progress – as we see regularly with the displacement of entire industries – is inherently disruptive, which brings me to the second key benefit of a free media. Because it also provides a channel for people to voice discontent without resorting to violence.

If problems and tensions are bottled up then they are far more likely to boil over. Stopping journalists from reporting a problem does not make it go away.

In February, The Citizen in Dar-es-Salaam reported a decline in the value of the Tanzanian shilling. How did the Government of Tanzania respond? By forcing the newspaper to close for a week. This might have helped the Government to vent its frustration, but it did nothing to revalue the shilling.

The truth is that when governments start closing newspapers and suppressing the media, they are more likely to be storing up trouble for the future than preserving harmony.

And far from being a cause of instability, responsible journalism and free media should help to avoid it.

Corruption is one of the biggest sources of anger in many countries. But far more effective than the crackdowns regularly launched by authoritarian regimes is the sunlight of transparency – just witness the striking overlap between the least corrupt countries in global indices and those with the freest media.

Indeed no fewer than seven of the top 10 cleanest nations in the world, as ranked by Transparency International, are also in the top ten for Press Freedom. And there is no mystery why. Powerful people care about their reputations. They are therefore far less likely to abuse their positions if there is a real risk of exposure.

But I make these arguments as someone who has grown up in a country with a free media. However I only timidly follow in the footsteps of many brave African writers, thinkers and journalists who have been fighting for the cause of media freedom at great personal risk.

Chinua Achebe, the late Nigerian author, said that his country needed a “flourishing free press that will exert checks and balances and put anti-corruption laws on a firm footing”.

And perhaps the greatest freedom fighter that Africa has known, Nelson Mandela, described a “critical, independent and investigative press” as the “lifeblood of any democracy”.

He added: “It is only such a free press that can temper the appetite of any government to amass power at the expense of the citizen…It is only such a free press that can have the capacity to relentlessly expose excesses and corruption.”

Media Freedom campaign

I want Britain too to play its part in championing media freedom.

So I’ve joined my Canadian counterpart, Chrystia Freeland, to launch a global campaign to protect journalists doing their job and promote the benefits of a free media. In July, we will host the world’s first ministerial summit on media freedom in London.

Amal Clooney will serve as my Special Envoy, bringing to bear her expertise as a human rights lawyer. She will convene a panel of experts to recommend ways of strengthening the legal protection of journalists.

On this and other subjects, we want to work closely with the African Union and UNESCO, who I thank for hosting us today.

Our overriding aim is to shine a spotlight on abuses and raise the price for those who would murder, arrest or detain journalists just for doing their jobs.

At the same time, we shouldn’t forget the international context Channels like RT – better known as Russia Today – want their viewers to believe that truth is relative and the facts will always fit the Kremlin’s official narrative. Even when that narrative keeps changing.

After the Russian state carried out a chemical attack in the British city of Salisbury last year, the Kremlin came up with over 40 separate narratives to explain that incident. Their weapons of disinformation tried to broadcast those narratives to the world.

The best defence against those who deliberately sow lies are independent, trusted news outlets. So the British Government is taking practical steps to help media professionals improve their skills.

In Ethiopia, our Embassy has provided training from international experts for 100 journalists in the last 2 years.

And today I can announce 2 further elements of support.

Firstly, Britain will provide £15.5 million to support next year’s election in Ethiopia, including by helping the National Election Board to run a free and fair contest.

Secondly, I am today inviting applications for a new Chevening Africa Media Freedom Fellowship. This will create an opportunity for 60 exceptional African journalists over the next 5 years to gain experience in the newsrooms of Britain’s leading media organisations. This year, applicants from 11 African countries will be eligible, including Ethiopia.

Conclusion

Let me close with the words of the South African novelist, A.C. Jordan, who wrote in the Xhosa tongue and whose books were only recently translated.

In his book The Wrath of the Ancestors, Jordan portrays ‘truth’ as a formidable wrestler, locked in combat with ‘falsehood’.

He writes: “But truth there is, without doubt. And it is the greatest force of all. For however you much you beat him with your sticks, however fast you chain him, I swear there will be a time when truth will escape from his chains and throw you to the ground, hurt and ashamed.”

That describes, quite simply, what the best journalism is all about. By helping truth to prevail, a free media ultimately helps us all to flourish.

Leading experts discuss media freedom around the world

How to watch this YouTube video There's a YouTube video on this page. You can't access it because of your cookie settings. You can change your cookie settings or watch the video on YouTube instead: Leading experts discuss media freedom around the world

Watch leading experts discuss media freedom around the world.

Find out more about: