How qualifications can reflect the FELTAG recommendations

Jeremy Benson speaks to the FELTAG conference about technology in assessment.

Good afternoon.

I can’t hope to compete with Bob Harrison’s presentation earlier, but I thought I’d kick off with a family story and a couple of amusing photos to illustrate a theme for the day and for what I want to say: technology should be a tool with a clear purpose, not an end in itself. And it needs to be used well.

Thinking about today’s conference, I asked my daughter about the on-line homework management service used by her school and she rolled her eyes and said, ‘well it’s fine when the teachers remember to update it’.

And I rather like this, playing back into the discussion before lunch. Even back in the 1960s the Jetsons were predicting that robots would be stood at the front of a classroom.

Although interestingly here, the robot appears to be stood in front of a good old-fashioned chalkboard, maybe about to throw a board rubber.

Whereas in reality it tends to be the other way round: humans stood there at the front, but using more up to date technology.

That interaction between learning and technology, between humans and machines, between the potential for IT and how it’s used in practice; all issues that apply equally to assessment.

And I’m going to concentrate today on assessments - that is, summative assessments - and the qualifications they lead to; you’d expect that from the qualifications regulator.

I’m going to discuss the opportunities to make better use of technology in assessment. How should innovation in qualifications sit alongside innovation in teaching? And what should Ofqual’s role be in that, as the regulator?

To provide some context for those questions, I’m going to start by giving a run-through of our regulatory approach and thinking, and some changes we’re making at the moment.

Let me start with validity: the ambition of every assessment and every qualification - measuring what needs to be measured.

That applies to any sort of assessment, from an old fashioned pen-and-paper exam to a dynamic on-line assessment. It should be the best way of measuring what needs to be measured.

We have no bias in favour of, nor against, technology in assessments. But we have an unapologetic bias in favour of good, valid assessments.

Of course there is often no single best way of assessing something - assessment is so often a compromise. And sometimes different approaches are needed - to test, for example, whether someone has a skill, and also whether they have the knowledge and understanding to know when and how to use that skill.

One good example of this, albeit not a qualification, is the driving test. Students must pass their theory test, but this only examines knowledge of the rules of the road, not the techniques of driving. For that we have the practical driving test. Only if you pass both are you deemed fit to drive.

The theory test is done on screen, because that is a valid, efficient way of doing that test. The practical test, though, remains practical: the most valid way to test whether someone can drive is to watch them drive and to see how well and how safely they cope with being on the road.

So validity is important. How do we regulate for it?

Well, to be clear, we’re not in the business of checking the validity of every single assessment of every single one of the thousands of qualifications we regulate. Even if we had the capacity and expertise to do that, it would not be an efficient, proportionate approach to regulation.

Rather, we set requirements of the awarding organisations we regulate. It is their job to be the experts in the types of assessments they’re offering: to design, deliver and award valid qualifications. Our job is to set clear requirements and check, on the basis of risk, whether those requirements are being met - and of course to consider taking action where they are not.

Awarding organisations therefore need the right capacity and capability. And I’ve set out here some of our expectations of their assessments; they:

- should be fit for purpose - that means, of course, they need to have a clear purpose

- can be delivered efficiently - an assessment must be manageable by the college or other provider offering it

- are cost effective - we know budgets are under strain

- permit reasonable adjustments to be made so people with disabilities can be fairly assessed

- allow learners to generate evidence that can be authenticated, so everyone can be confident in the integrity of the assessments

But as the regulator, it’s not our job to decide what should be studied or how it should be studied, or what qualifications should be available, or what should be funded from the public purse. It’s our job to make sure that whatever qualifications are offered, they’re valid in the widest sense.

Nor is it our job to specify approaches to assessment. Whether they should use essay questions or multiple choice, or both, or neither, and whether they are on-line or on paper: what matters is, are they valid, and how can the awarding organisation demonstrate that?

I want to make one final, important point about our regulatory approach.

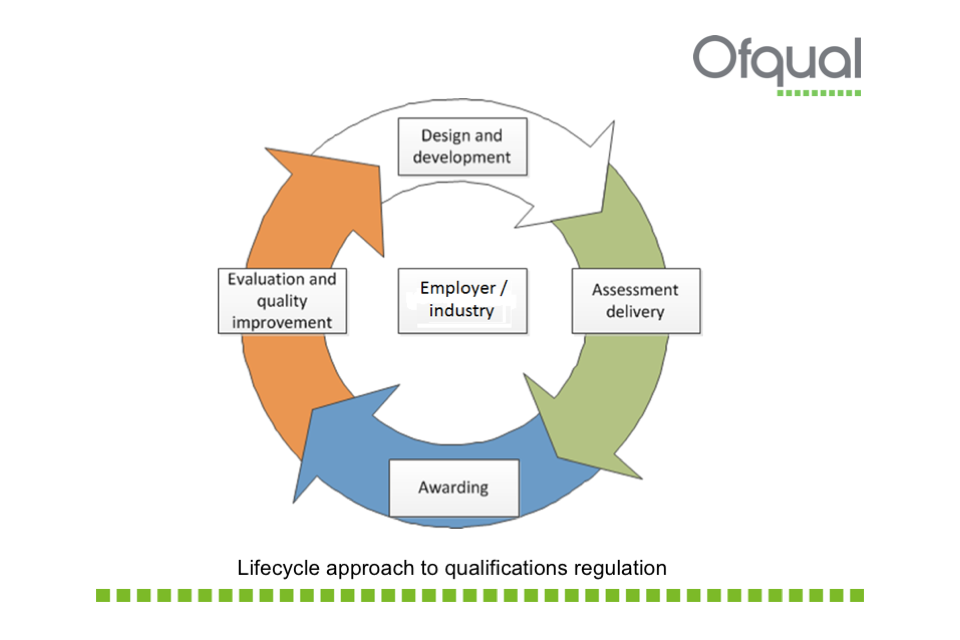

We need to look at the whole lifecycle of a qualification, and to test awarding organisation compliance with our conditions at different points in that lifecycle.

Too often it’s assumed that it’s enough to check a qualification up-front and then let it happen. But in fact, that’s not enough. Every bit of the lifecycle needs to be right. A well-designed qualification can be poorly delivered.

So, whatever type of assessment is used, the processes for securing consistency in the standards of ongoing assessment need to be right. The arrangements for standardising assessor judgements need to be right. The standard-setting decisions need to be consistent. The arrangements for reviewing how qualifications are used need to be effective, and to feed back into the ongoing improvement of the design and operation of the qualifications.

That’s why we removed the accreditation process from our regulatory approach, except for certain qualifications - like GCSEs and A levels - where there’s a good case for it.

We are taking a risk-based approach to determining validity, systematically analysing the information we gather about qualifications and then judging where to focus our regulatory activities. These activities include audits, investigations and technical evaluations of awarding organisations and of their qualifications.

At all times we are testing compliance with our rules and we are ready to take action when we find non-compliance, from directing improvement to fining, or at the most extreme, forcing an awarding organisation from the regulated market.

In other words, regulating.

In case you are not aware, today is an historic day. The last day of September is the last day of the Qualifications and Credit Framework rules. Following extensive review, consultation and discussion over the last couple of years we are removing the QCF rules as of tomorrow. This will free up the awarding organisations to do more interesting, innovative things with their qualifications - a more important change, I think, than anything else we could have done, and of course fully in line with the first of the FELTAG recommendations on regulation.

When the QCF was introduced, the idea was to have a building block approach to learning where students could piece together units of learning, using credit to build qualifications and support their individual progression needs. The QCF therefore set detailed rules about how qualifications should be designed. The problem was that this approach did not work for all types of qualifications or subject areas, and it did not provide any guarantee of quality.

The specific rules introduced to make the QCF work placed much focus on consistency around how qualifications should be structured, but did not focus nearly enough on validity. The rigidness of the rules also meant that awarding organisations found that they could not always take the approaches to assessment that most suited what was being taught. Awarding organisations also told us that the rules, at times, stopped them from innovating.

We weren’t really surprised then, that when we consulted on removing the QCF rules last year, there was widespread agreement with our proposals. We’ve worked closely with awarding organisations, government and other agencies to take the best approach to withdrawing the rules.

Note that I’ve talked about removing the QCF rules, not removing QCF qualifications. If awarding organisations are satisfied that their qualifications designed to meet the QCF rules are valid, then we will not require them to be changed just because the rules are no longer in force. Unlike when the QCF was introduced, we are not requiring a big, disruptive investment in changing existing qualifications.

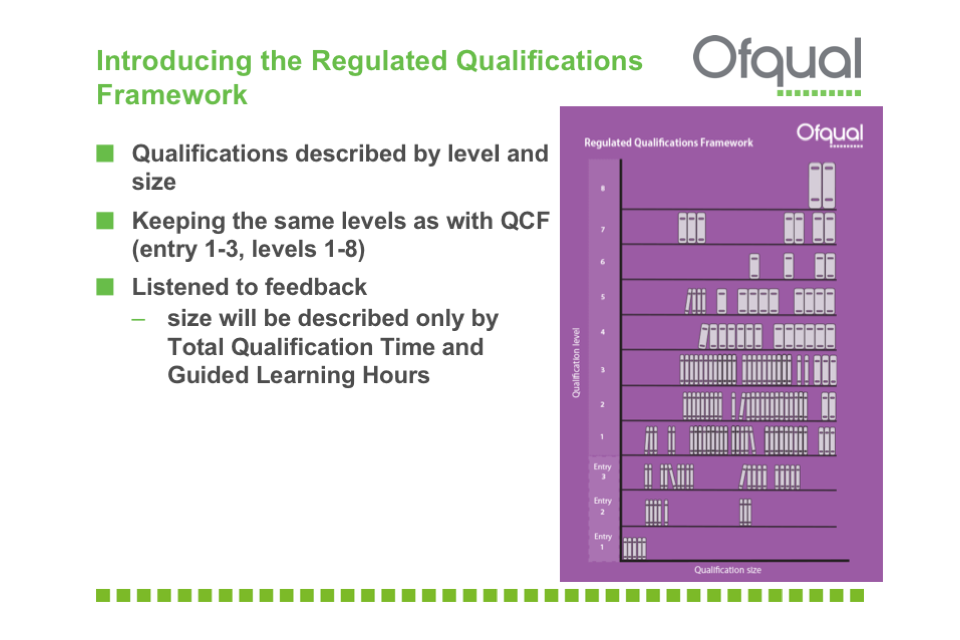

I hesitated a bit before including this slide, which tries to explain our new regulated qualifications framework using the analogy of a bookcase.

Unlike the QCF, which took a prescriptive approach - prescribing how qualifications should be designed - our new framework, called the RQF, is a descriptive framework. It seeks to help people to understand something about the qualifications we regulate: how demanding they are and how big they are.

Just like books on a bookshelf: you can tell something about a book from which shelf it’s on. The RQF carries forward the previous levels, though with some changes to the detailed descriptors, from Entry Level up to Level 8, which is doctorate level. You can also see at a glance how big the book is.

But of course what really matters is what is in the book - just as what matters in a qualification is what skills and knowledge it is testing. For that, you need to look in more detail. We do have an online solution to that - we are developing a new, more user-friendly register of qualifications with greatly improved search functionality. Do have a look at the alpha version on our website.

I should mention too that there was concern from Bob and some of his colleagues that our original proposals weren’t sufficiently e-friendly. We considered these concerns and decided that they were right. So we changed and simplified our plans. Qualification size will now be measured through Total Qualification Time, or TQT, with Guided Learning Hours as a subset of that. These values make no assumption about delivery or assessment methods.

So the removal of the QCF and the changes to the framework serve to free up a clogged regulatory space, and say to the awarding organisations: right, over to you now. The way is clear for you to produce the best qualifications you can, and to innovate if you will.

So let me turn now to the question of innovation in assessment.

As ever, our main question for assessments - innovative or not, technology-enabled or not - is: are they valid? And I would suggest that this is a good starting point for awarding organisations and others thinking about innovation too.

But there are other questions to consider as well, when thinking about the reasons for innovating. As I said at the beginning, technology is not an end in itself.

Technology can enhance assessment - allow skills or knowledge to be assessed in more valid or efficient ways. It may be fairer if it reflects more closely how students have been taught - though it’s not essential for innovations in teaching to feed through into assessment approaches; they are different types of things. People should not assume that things taught on-line need to be assessed on-line, or vice versa. Assessment needs to be consistent enough across the country that the awarding organisations can be confident that the standard is the same; that the qualification awarded in Newquay means the same as the qualification awarded in Newcastle.

Perhaps assessment can engage students - though not at the expense of validity of course.

And technology can make some assessment risks easier to manage, but introduce some new ones too.

So by all means innovate in assessment. But be clear why you’re doing it. Focus on validity. And don’t bundle assessment in with teaching, or assume that the approaches that work there will always work for assessment.

So what does this mean for how we regulate?

The main risk for any regulator is always that we get in the way of innovation. We might set rules that assume particular ways of doing things or prevent risk-taking. As I’ve said, the QCF was a good example of that.

That’s why we have a legal duty to have regard to the desirability of innovation. A duty, of course, that we take very seriously. Our aim is to allow and to enable awarding organisations to innovate, including in the use of technology, and not to be constrained by our rules. Our rules are therefore outcome-focused, looking at what qualifications are aiming to do and trying not to make assumptions about how they might do it. And we invite awarding organisations to tell us where we’re getting this wrong - this very issue was discussed through the FELTAG process.

So of course we are keeping our rules under review with innovation and technology in mind. We intend to set out by spring next year our approach to innovation. We will shortly be starting discussions, initially with awarding organisations, to check that our approach to regulation isn’t preventing innovation. Other regulators will be producing innovation plans too.

Let me emphasise, though, that it’s not our job to push innovation. The world needs people who challenge existing thinking, encourage risk-taking, rethink what a qualification should be in an e-enabled world. But if we were to do that, there would be no one to do that boring but important task of making sure that the qualifications, so important to students’ life-chances, could be trusted.

No, the best a regulator can do is enable, and not get in the way. We cannot and should not try to force technology on awarding organisations: if there are old-fashioned approaches to assessment that remain valid and appropriate, it’s not our job to try and stop that. The leadership for and the demand for innovation needs to come from elsewhere: from the market, from employers, from policy-makers, from funders. All of you in this room can play a role here.

We will also be looking at how we can make better use of technology ourselves.

While we have been consulting about removing the QCF rules, we have also been in discussion about replacing our current regulatory IT system, to develop something that is more responsive to the rules that will be in place in the future. We have been careful to refer to those who have to use the system, to make sure that the new system minimises burden, streamlines the data we collect and doesn’t have a negative impact on the system’s users when it’s introduced. It will also enable us to better interpret the data we collect, giving us even more intelligent insight into the qualifications market. And it will support the new register of qualifications which I’ve already mentioned.

** slide 11 So it will not surprise you to learn that we were broadly comfortable with the first half of the FELTAG recommendation. If others want to encourage e-assessment, fine. Our only stipulation: yes, it should be valid.

But should half of all vocational assessments be online from 2018/19? I don’t know. That might be too much or even too little, and I don’t know how that figure was arrived at.

In particular, I don’t see how some of the critical assessments of occupational competence - such as plumbing or welding - could be validly assessed on-line, and I found it quite disappointing that the FELTAG report did not acknowledge or engage with that issue. And such a blanket target risks looking like ‘technology for the sake of it’. I don’t think that’s what anyone wants.

That said, I take this recommendation in the spirit I think it was intended: as a healthy challenge to the qualifications industry. And there is much still to be done to make the case and engage with assessment experts on the issues it raises.

Though we should acknowledge that there has been investment in technology by the awarding organisations.

** slide 12

Here are some of the things that already happen in different parts of the qualifications world.

The bigger exam boards offering GCSEs and A levels conduct almost all of their marking on screen now, using technology to scan and then issue questions to markers around the country - even the world in some cases - and carrying out training and standardisation of markers through online forums and webinars as well.

Many functional skills and other qualifications are now assessed online, using on-demand assessment. Some awarding organisations offering high volume qualifications have found that it’s made both operational and commercial sense to move course administration and some testing online. Technology is being used to streamline processes for student registration, monitoring of student progress, requesting moderation and printing certificates.

Assessment has moved online, for example multiple choice tests, where online portals can provide individualised tests in what are effectively internet ‘safe zones’. Organisations use algorithms that pull questions randomly from question banks, and these algorithms ensure the standards of the tests remain at the right level of demand, while making sure that all the students do not receive the same questions, thus preventing too much predictability in the test.

What’s important is that the technology is being used to support the validity and efficient delivery of some assessments, by some awarding organisations.

** slide 13

But I know that some of you will feel that there is so much more that could and should be done. That ‘some assessments by some awarding organisations’ is not good enough for 2015.

So let me finish with what I hope is a constructive suggestion.

If I was one of those of you frustrated by the slow pace of change, I would be developing a three-point action plan that - in outline - looked something like this.

First, make the case. What are the opportunities that technology offers assessment? How can it improve validity, reliability or efficiency? What global examples can you point to that show what can be achieved? What can ‘thinking differently’ look like for assessment? Where is there a need to disrupt conventional thinking about qualifications? And what does that mean in practice?

Second, try and create demand. Particularly in tough times, awarding organisations - whether they are commercial or charitable bodies - will respond to what their customers are looking for. When colleges demand more interesting, innovative assessments; when they start asking for advice and support on improving technology through qualifications - then awarding organisations will have an incentive to start investing in them; as David said earlier, to use technology well requires investment - it’s not a cheap option for assessment more than any other area. As someone said recently, don’t wait for Westminster; don’t expect a top-down target to do the trick. And, by the way, don’t expect Ofqual to mandate e-assessment, because we won’t.

Third, recognise that there are some real challenges as well as opportunities in rolling out e-assessment. Talk to the awarding organisations about how you can help them to learn from good practice including overseas, to research what works and what doesn’t, and to try out different approaches.

I think there’s a gaping space here where there could be leadership, vision and innovation, to take the qualifications industry forward.

And what about Ofqual? We’ll be watching with interest. We’ll help you if we can to try and make connections with the awarding organisations. We’ll be trying not to get in the way. And - yes - we’ll keep focusing unashamedly on validity. On-line or on paper, what we’re about is good qualifications.

Thank you.