Modernising Development Finance: the future of Official Development Assistance (ODA)

Mark Lowcock delivered a presentation on “Modernising Development Finance”.

Slide 2

ODA system has been very successful in motivating efforts for development. Modernising is about ensuring that it remains so.

I will structure my presentation in three parts:

- Provide context on the history of development finance, especially ODA and its changing role.

- Explain why we want to engage in a discussion on development finance and the ODA definition.

- Share UK perspective on priorities for modernising ODA.

Slide 3

- UK will hit 0.7% this year – as the first G8 member to honour our promise to spend 0.7 per cent of Gross National Income on development.

- This is the right thing and the smart thing to do. Tackling poverty in the world’s poorest places means tackling the root causes of global problems such as disease, drugs, migration, terrorism, and climate change. It creates a safer and more prosperous world and matters to us in Britain.

- Coalition Agreement said we would achieve 0.7% in compliance with DAC rules and the International Development Act 2002.

Slide 4

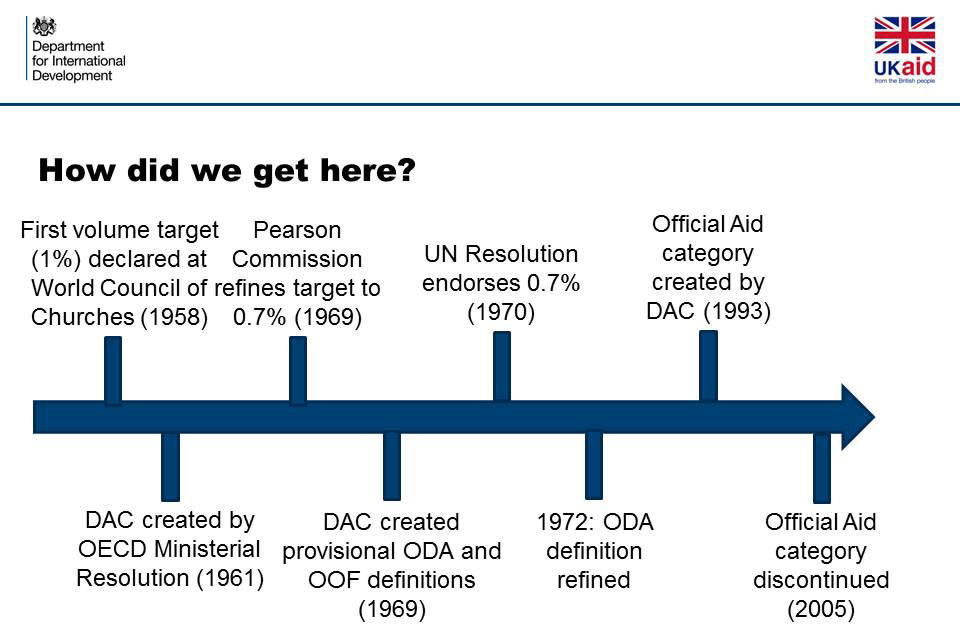

- First introduction of volume target in 1958 through Geneva-based World Council of Churches: “(…) if at least one per cent of the national income of countries were devoted to these purposes, the picture would become much more hopeful”.

- This 1% target already included private flows, it was a round number that roughly represented a doubling of capital flows from the levels of the mid-1950s.

- All the then DAC members subscribed to it in 1968. But no means of programming or even predicting the private element of capital flows, which in many years are more than half the total.

- This stimulated efforts to define a separate sub-target for official flows. The Dutch Economist and Nobel Prize winner Jan Tinbergen – as Chairman of the United Nations Committee on Development Planning - estimated the capital inflows developing economies needed to achieve desirable growth rates, and proposed a target for official flows - both concessional and non-concessional - of 0.75% of GNP, to be achieved by 1972. This target was then refined by the Pearson Commission which deducted net value of non-concessional flows and reached 0.7% ODA target.

- Political context: In UN negotiations country groups already used crude trade-offs between ODA and other commitments.

- Formal recognition in October 1970 in UN General Assembly: “each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7% of its gross national product at market prices by the middle of the decade.”

- This built on the definition of this concept by the DAC in 1969 (refined in 1972).

Slide 5

- 5 core elements of the 1972 definition form the ODA definition we still use today:

- the type of flows (equity, grants, loans or technical cooperation);

- the source (official sector of donor countries);

- the recipients (they must be on the DAC list);

- the development/welfare purpose of the related transactions; and

- their concessional character.

- Many aspects of the current debate were already present in 1972: private versus public, concessional vs. non-concessional

- Other official flows (OOF) category introduced in 1969.

- OOF captures transactions from the official sector with countries on the DAC list of ODA recipients which do not meet ODA eligibility criteria.

- As not counted towards 0.7 target very little traction in political debates and arguably low donor incentives.

- From 1993 to 2005 we had a more differentiated system with two DAC lists – one for “traditional” developing countries/ ODA and a separate list, for “more advanced” developing and Eastern European Economies, then called “official aid”. Official aid was on top of ODA and did not count towards the 0.7 target. Since 2005 only one list of DAC ODA recipients in place.

Slide 6

- The ODA system has three core pillars:

- The definition

- The volume target

- The governance system

- The ODA system is characterized by unusual governance: target definition and measurement in peer pressure are based in the OECD-DAC but target setting and accountability take place in the UN. This distinction present from the beginning.

- Dual purpose/perspective of ODA definition – outcomes and total resource flows versus burden sharing and donor effort.

- Past debates mainly about inclusion or exclusion of specific areas, current debates more focused on how to capture financing instruments that do not fit the ODA definition.

- New frontier transparency: Busan common transparency standard. We have now over 160 IATI publishers of all shapes and sizes, G8 agreed Open Data Charter.

Slide 7. Chart: Development Initiatives, 2013, Guide to ODA, p. 4.

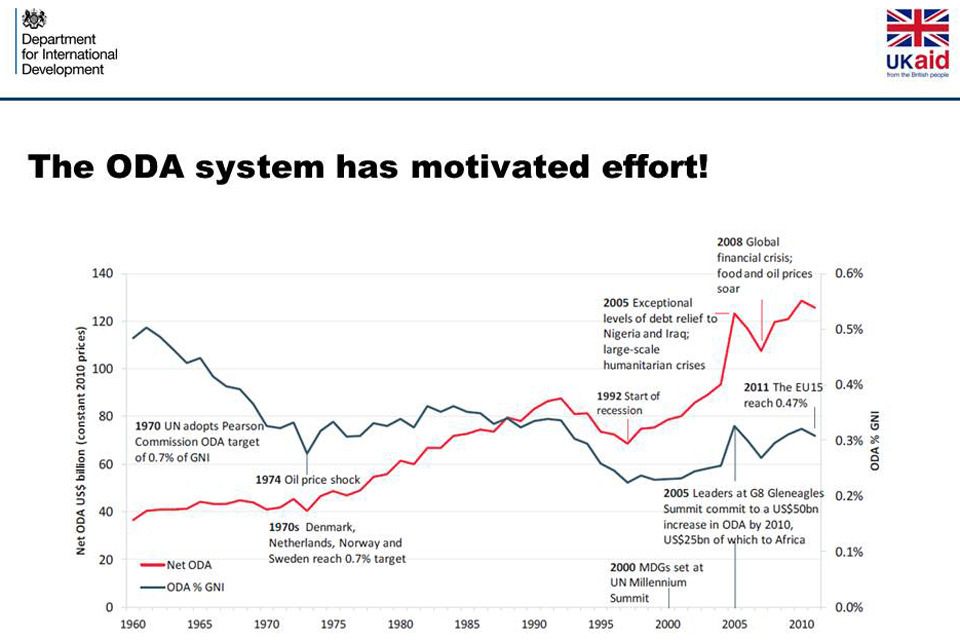

- The ODA system has encouraged effort: Powerful combination of MDGs and 0.7% target has contributed to a significant increase in political support for official development finance and a sharp increase in ODA levels since 2002.

- ODA has increased from 78.7 billion in 2000 to 125.5 billion in 2011, i.e. by 63%.

- EU Heads of States and Governments Commitment in 2005 with specific timetable and highest level accountability mechanism and G8 commitment in Gleneagles.

- While no comparable relevance of 0.7 target, European action spurred debate in US.

- Comparison with “national expenditure” shows that ODA all in all a good measure of donor effort.

Slide 8. Chart: Development Initiatives, 2013, Guide to ODA, p. 7.

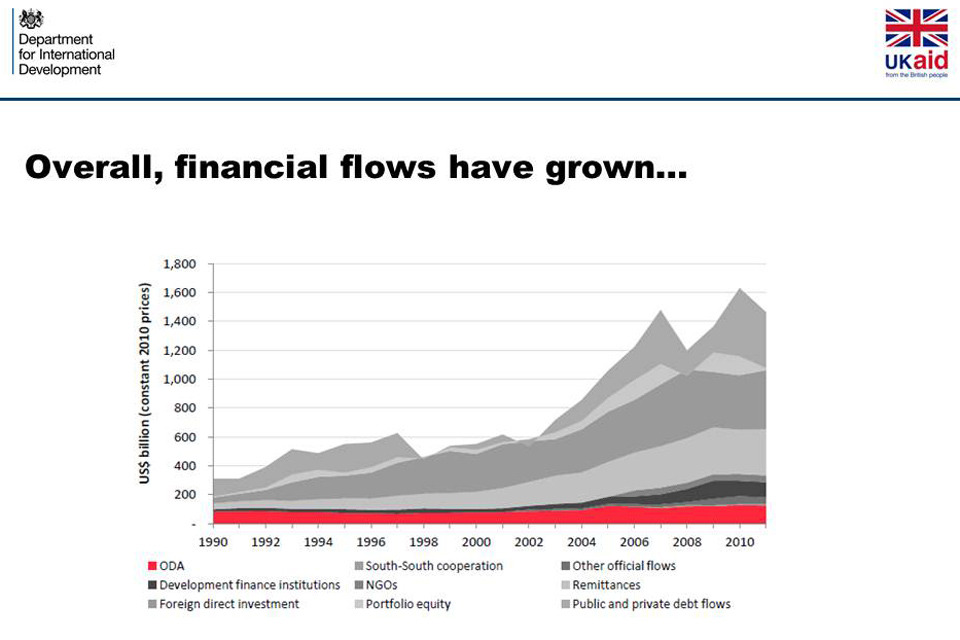

ODA in context – Overall financial flows have grown….

- Over the past 23 years financial flows other than ODA have increased dramatically.

- Public and private debt flows, remittances, Other Official Flows (OOF) and portfolio equity have undergone drastic growth.

- These developments affect the financial landscape that ODA operates in but do not decrease the importance of ODA

Slide 9. Chart: Development Initiatives, 2013, Guide to ODA, p. 8.

However, ODA is still very important in LDCs

- Government expenditure is increasing in all developing countries (Figure A) but it is significantly lower in LDCs (Figure B)

- ODA also plays a much greater role in these countries

Slide 10. Chart: Development Initiatives, 2013, Guide to ODA, p. 24.

ODA in context continued

- The current ODA definition and development assistance providers have recognised where ODA makes an important contribution.

- The share of ODA going to LDCs has been increasing since 2005.

- However, in 2012 bilateral net ODA to LDCs fell by 12.8%. In real terms this reduced the total figure to $26 billion.

- This increase goes hand in hand with a surge in the number of loans by a some donors indicating the need to protect ODA for LDCs.

Slide 11

- ODA definition has been a credible quality standard focused on broad development objectives, maintained by DAC governance structure, peer pressure to provide data, and rigour of DAC Secretariat’s reporting.

- Wider system encourages aid and development effectiveness

- Peer reviews

- Good practice guidelines

- Untying of aid

- Paris/Accra/Busan Agenda

Slide 12

- Credibility: 0.7% target has not been met collectively in 40 years. Sweden and the Netherlands reached the target in 1975, Norway and Denmark reached it in 1976 and 1978 respectively, and all four countries have consistently met it since. Finland achieved it once, in 1991. Luxembourg reached it in 2000 and continues to do so. Since then UK will be first country to join this group.

- Relevance: in the changing landscape of development financing is ODA still relevant?

- Actors: Important flows from non-DAC donors are outside the system, preventing scrutiny of quality, assessment of burden share.

- Instruments: ODA definition can create perverse incentives. Political recognition is almost exclusively for ODA; there are few incentives to provide other official flows (OOFs) of development finance. Little incentive for innovative financing mechanisms that could mobilise significant amounts of private investment through risk mitigation instruments (e.g. guarantees) as they are not adequately captured as ODA. More credit given to investment projects (equities) that fail, since proceeds of equity sales all count as negative ODA.

Slide 13

- There has been a lively debate on relevance and modernisation of ODA

- Three influential papers:

- Severino’s 2009 paper on the “End of ODA: Death and Rebirth of a Global Public Policy”

- Minouche’s 2011 paper on the “Future of Development Finance”

- Rogerson/Kharas 2012 Horizon 2025 paper “Creative Destruction in the Aid Industry” which identified three “disruptors” to traditional aid:

- Private giving (high-impact philanthropy and non-governmental channels)

- South-South Cooperation (combining trade/finance and public-private funding)

- Climate finance (political traction and different allocation logic)

- Letter to FT from former DAC Chair Richard Manning on DAC interpretation of “concessional in character”: “OECD is encouraging OECD finance ministries to get away with murder as they seek to massage reported aid upwards at minimum cost”

- The DAC agreed at December 2012 High Level Meeting in London to develop:

- A new measure of donor effort

- A new measure of recipient benefit

- A new category of total official support

- In light of results revisiting ODA?

- But also: UN Development Cooperation Forum at meeting this spring:

A renewed global partnership must build on ODA as a vital part of development finance. The commitment of realizing 0.7% of GNI as ODA must be fulfilled. The modalities, principles and conditionality of ODA need to be revisited. It should become more comprehensive and serve as a catalyst for promoting trade, investment and technology transfer for development.

- The HLP Report called for a renewed global partnership and suggests goal No 12 “to create a global enabling environment and catalyse long-term finance.” It covers ODA, voluntary targets for complementary financial assistance as well as tax evasion, illicit flows and stolen asset recovery.

Slide 14

- To recap: we want a development finance system that builds on the success of the ODA system, focused above all on the MDGs/post MDGs.

- For us, this is a discussion about motivating effort on development – in terms of volume and quality. We’re interested in total support for development, not just ODA.

- It is about encouraging all actors to do the right thing in the right places with the right instruments.

Slide 15

- To motivate effort effectively we must consider:

- Effort from whom?

- Effort for whom?

- Effort for what?

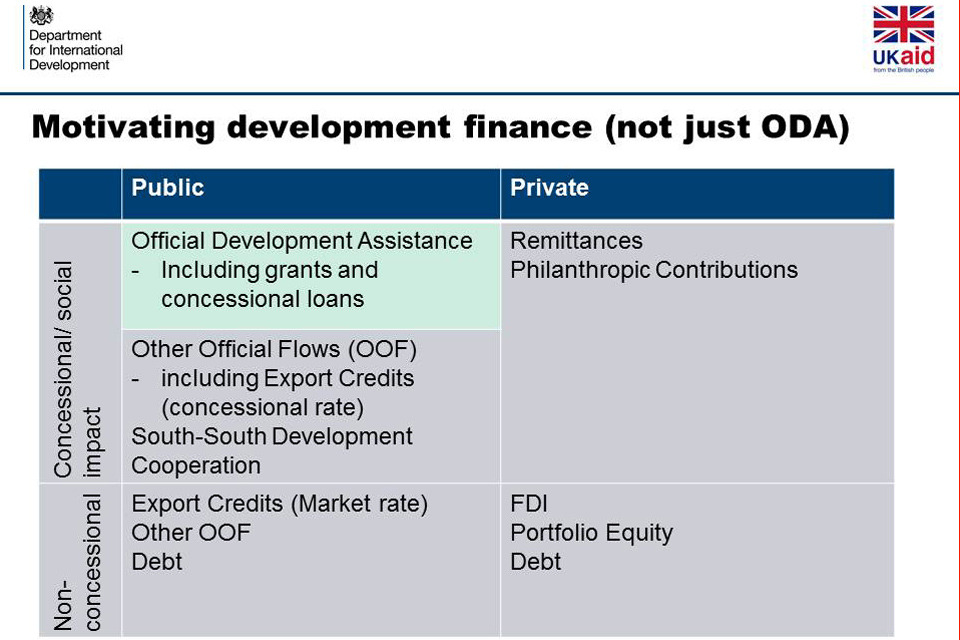

Slide 16

- The questions mentioned are of course relevant for ODA, but they are relevant in each of the four boxes. Important to keep this in mind.

- We are interested in motivating effort in each box independently.

- How ODA can be used to maximise the development impact of private nonconcessional flows.

- DFID currently works on the following areas:

- Directly: sharing risk with private investors in frontier markets and sectors to demonstrate that these investments can be commercially viable. Can be to overcome:

- information failures (e.g.. not as risky as perceived);

- first-movers costs in new countries, sectors, markets where the first investor faces additional cost which are essentially a public good (e.g.. how does a regulatory system work in practice etc);

- risks the private sector cannot manage (e.g.. political risk)

- Indirectly: We also support the development of an investment climate that enable private investors to have confidence to invest.

- We support market development, to put in place or strengthen the market infrastructure or systems that are required for the market to grow and succeed.

Slide 17

- Domestic efforts are the most important, but this is not my topic today.

- DAC members still the most important group, and are drawing in others, e.g. Turkey, Russia, Kuwait, UAE, Gates, who report their flows.

- But also: DAC is perceived by some as “donor-club”, not right forum for South- South cooperation providers which view their cooperation as distinct from DAC donors ODA by motivation and instruments.

- UK bilateral relationships with aid agencies and ministries in China, India, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Gulf etc.

- Is there potential to establish a dialogue on external development financing, which would bring South-South Cooperation as well as DAC members into an agreed framework, perhaps with major foundations and charitable providers. Could this help to provide transparency, clarity about scale, analysis of development impacts and shared learning?

- Role of Global Partnership on Effective Development Cooperation.

Slide 18

- If goal is achievement of MDGs/post MDGs, there is a strong efficiency argument to focus grant resources on the poorest.

- However, the current system does not differentiate between a country such as Mali with a GNIof $660 per capita and Seychelles with a GNI per capita of $11,640.

- Countries graduate only when they reach high-income level or join the G8 or EU. The last revision of the DAC list of ODA recipients included the graduation of Oman and Croatia but not, e.g. Mauritius, Mexico or Brazil.

- And there is a worrying trend: the OECD Outlook on Aid, a survey on donors’ forward spending plans 2013-2016, states that while overall aid levels are expected to bounce back in 2013, there is no additional money for the poorest countries. It notes that: “the major increases […] in country programmable aid are projected for middle-income countries in the Far East and South and Central Asia, primarily China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan and Vietnam.” For the countries that experience the largest MDG gaps and poverty levels, the survey reveals a significant reduction in programmed aid.

- So we need a better and faster process for graduating from ODA.

- Graduating richer countries from ODA earlier should go hand in hand with establishment and upgrading of a new category which continues to motivate effort (not only finance but expertise/experience and ideas) for no longer ODA-eligible countries. Should we re-introduce the “official aid” category?

Slide 19

- The ODA definition – which requires expenditure to have economic development and welfare in developing countries as its main objective - is largely fit for purpose.

- But some improvement desirable, especially to remove some perverse incentives.

- Example 1: current system for recognising effort through Development Finance Institutions for promoting private sector development rewards failed equity investments and penalises successful ones.

- Example 2: many countries are held back by conflict and insecurity. Efforts to help tackle that are weakly recognised. So (a) only 6% of contributions to UN mandated peace keeping operations score as ODA despite many modern missions having significant civilian components, and (b) demining operations carried out by civilian contractors are eligible, while those carried out by military personnel are mostly not.

- Example 3: because ODA is a flow concept, no recognition is given for other support. Lots of scope for using guarantees, for which donors take a fiscal risk but get no credit (unless the project fails and the guarantee is called!).

- Another example of this relates to the International Finance Facility for Immunisation which uses long term legally binding pledges from donors as security to raise finance on the private capital markets. The funding raised in this way supports childhood immunisation programmes in poor countries.

- From 2006-March 2013 IFFIm disbursed $2.3bn to the GAVI Alliance for immunisation programmes, delivering about half of GAVI’s overall programme spend since its inception. To date, GAVI has immunised over 370 million children and saved 5.5 million lives, using a mixture of core and IFFIm funding.

- DFID is the major financier of GAVI and we take on to our balance sheet the full risk at the time of each bond issue, which is also when the development benefit arises. But the ODA system recognises our effort only as we service the bonds over the next, say, 20 years.

Slide 20

- Example 4 relates to the current definition of concessionality used by the DAC. The current arrangements could permit some members to borrow at 1-2%, lend on at a profit (at say 3-5%, still cheaper money than many ODA recipients can access from the markets) and claim the whole transaction as ODA. Richard Manning, former Chair of the DAC, in a noteworthy letter to the Financial Times earlier this year, likened this to “getting away with murder”.

Slide 21

- ODA system has been an important global public good – has motivated high quantity and quality of development effort.

- Need for better development finance debate informed by rigorous analysis.

- Need to be clear what behaviour we will incentivise. What are 2nd and 3rd order impacts?

- We must meet ODA commitments and build a re-invigorated system for the post-2015 world.

- Not covered all the relevant issues today – a lot more to be said on domestic resource mobilisation, support for global public goods, tax issues (addressed at last month’s G8), transparency and reinforcing a stronger focus on results.

- Looking to you for leadership in this debate. Welcome strongly your commitment in recent letter from IFI Heads to UN SG to “help construct a robust framework for financing the Post-2015 Development Framework”, and “work to maximise the impact of ODA, support new development partnerships, leverage the private sector, deliver global and regional public goods, and tap new sources of finance”.