Opening remarks at the American Bar Association (ABA) Chair’s Showcase on AI Foundation Models

Remarks by Sarah Cardell, CEO of the CMA, delivered during the 72nd Antitrust Law Spring Meeting. Washington DC, USA.

Thank you for the opportunity to open this morning’s discussion with some reflections from the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) on our work on the impact of foundation models – or generative AI – on competition and consumer protection. I’d like to start by taking a step back to reflect on why this work matters - and why we think it’s important that it happens now. We know these models could hold genuinely transformative promise for our societies and economies, massively increasing productivity, transforming many existing products and services for both businesses and consumers, and bringing to market new innovations and as yet unimagined technology developments across all sectors of the economy.

It’s difficult to know when we are witnessing a true paradigm shift. By their very nature, pivotal moments in history are often characterised by heightened uncertainty. But we can be alert for signals that something is unfolding which we will later look back on and recognise as genuinely transformative.

As the Chief Executive of the CMA, looking across the fast-moving developments in both the development and deployment of these models, I feel a keen responsibility to ensure that we’re using the full range of the CMA’s powers to make sure those markets are underpinned by fair, open and effective competition, as well as strong consumer protection. And I think if you look at the statements and actions of various authorities around the world, including in Europe and here in the US, you can see a shared focus on this.

Why do I feel that responsibility? Because it is those conditions of fair, open and effective competition that will drive greater innovation, choice and lower prices for businesses and consumers, as generative AI is increasingly used across the whole economy. And it is those market conditions which enable independent start-ups and challenger firms to bring forward disruptive innovations, gaining ground on, and potentially upending, the entrenched market positions of today’s large, digital firms.

The foundation models ecosystem has experienced some genuinely groundbreaking advances recently, and is consequently moving at pace. That’s why we launched an initial review in May last year, publishing our analysis in a report last September. Whilst our analysis recognised the multitude of benefits these models might bring, we also identified a risk that the markets could develop in ways which would cause us concern from a competition and consumer protection standpoint.

To mitigate that risk, we proposed a set of underlying principles to help sustain vibrant innovation and to guide the markets toward positive outcomes. These are:

-

access: meaning ongoing ready access to key inputs

-

diversity: to ensure sustained diversity of models and model types

-

choice: enabling sufficient choice for businesses and consumers to decide how to use foundation models

-

fair dealing: by which we mean, for example, no anti-competitive bundling, tying or self-preferencing

-

transparency: in terms of consumers and businesses having the right information about the risks and limitations of models

-

accountability: ensuring developer and deployer accountability for outputs

Without fair, open, and effective competition and strong consumer protection, underpinned by these principles, we see a real risk that the full potential of organisations or individuals to use AI to innovate and disrupt will not be realised, nor its benefits shared widely across society.

Since last September, we have continued to track market developments and have engaged widely with a range of different stakeholders. We will be publishing an update report today, so this is an excellent opportunity to share some key highlights.

The foundation models ecosystem has continued to develop at a whirlwind pace, with a spate of industry announcements spanning new model launches, investments and partnerships, high-profile hirings (and in some cases firings), and a remarkable drumbeat of innovation and new use cases.

As exciting as this is, our update report will also reflect a marked increase in our concerns about the directional trend of these developments. Specifically, we believe the growing presence across the foundation models value chain of a small number of incumbent technology firms, which already hold positions of market power in many of today’s most important digital markets, could profoundly shape these new markets to the detriment of fair, open and effective competition, ultimately harming businesses and consumers, for example by reducing choice and quality and increasing price.

And in assessing this risk, we are determined to apply the lessons of history. As I look back at the rise of digital markets over the last 10 to 15 years, of course I ask myself whether competition authorities could, or should, have better predicted the pace and scale of digital transformation. Could we have responded faster to the competitive threats posed by large digital platforms, recognising earlier that the tools we had would need adapting to address the unique challenges posed by this new breed of businesses? With the benefit of hindsight, I think the answer is almost certainly “yes”.

Now we understand much more about digital markets. And it’s important to emphasise always the enormous benefits that technology has unlocked. But we have also seen the winner-take-all dynamics which have led to the rise of a small number of powerful platforms. And we have seen instances of those incumbent firms leveraging their core market power to obstruct new entrants and smaller players from competing effectively, stymying the innovation and growth that free and open markets can deliver for our societies and our economies. We have also seen that those firms can engage in behaviours that exploit people and businesses, like undermining choice and control through harmful online architecture, or through anti-competitive tying and bundling of products and services. So, while the eventual outcomes of the paradigm shift we may be witnessing in generative AI are currently uncertain, it’s important we take what we have learned into account as we consider our response.

The increased presence of the largest and most established technology firms across multiple levels of the foundation models value chain is happening both through direct vertical integration but also through partnerships and investments – including in the supply of critical inputs such as data, compute and technical expertise, in model development, and in the provision of products and services (like apps and platforms) allowing businesses and end consumers to access and deploy foundation models.

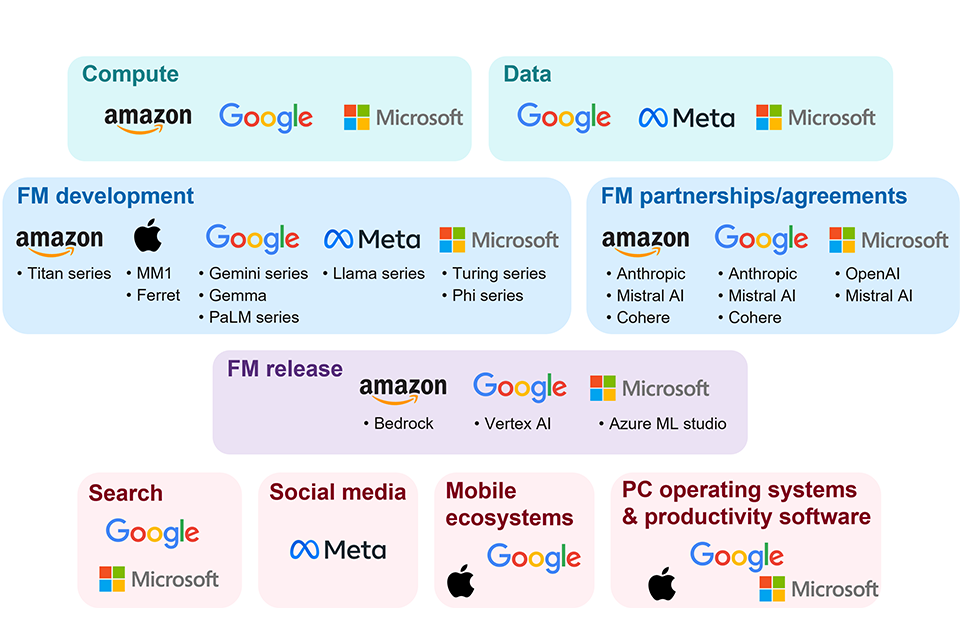

I’d like to share a chart from our update report which illustrates the point.

Figure 1: Illustration of the presence of GAMMA firms across the FM value chain [Footnote 1]

A description of this image can be found in the alt text section.

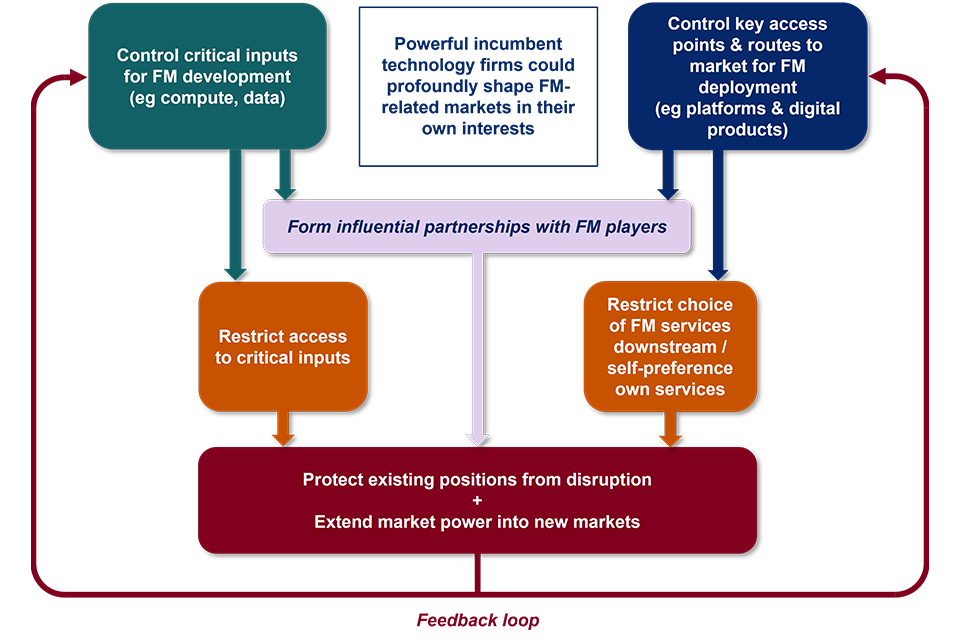

Some of these firms have strong positions in one or more critical inputs for upstream model development, while also controlling key access points or routes to market for downstream deployment. That creates a particular risk that they could leverage power up and down the value chain. At the same time, it’s possible that AI could have genuine disruptive potential in some markets where these firms currently have market power. In combination, this could mean that the incumbents have both the ability and incentive to shape the development of foundation model-related markets in their own interests - both to protect their existing market power and to extend it into new areas.

This chart from our update report neatly illustrates the point.

Figure 2: Incumbent technology firms could shape FM-related markets in their own interests

A description of this image can be found in the alt text section.

I’d like to be crystal clear here. We recognise that today’s largest technology firms likely have an important role to play as the markets for foundation models evolve. They have a huge wealth of resources and expertise to bring and, in some cases, have themselves been drivers of innovation in this space, as well as more broadly of course. But the benefits we wish to see flowing from all of this - for businesses and consumers, in terms of quality, choice and price, and the very best innovations, are much more likely in a world where those firms are themselves subject to fair, open and effective competition, rather than one where they are simply able to leverage foundation models to further entrench and extend their existing positions of power in digital markets. So, this really matters from an end user perspective.

It also matters because diversity and choice underpin resilience in our economy and avoid over-dependence on a handful of major firms – a particularly critical concern considering the breadth of potential use cases. Key sectors predicted to be impacted, in some cases already being impacted, include finance, healthcare, education, defence, transport and retail, to name just a few. They touch every area of our lives.

So we believe it is important to act now to ensure that a small number of firms with unprecedented market power don’t end up in a position to control not just how the most powerful models are designed and built, but also how they are embedded and used across all parts of our economy and our lives. Especially at the same time as authorities around the world are working so hard to address the market power held by the same companies in adjacent digital markets.

That takes us back to 2 of our proposed principles: Diversity and Choice. It is essential to preserve fully independent, competing offerings between different developers; and equally to protect genuine diversity and choice in the deployment of foundation models in any given use case. Particularly because history tells us technology markets can tip quickly to a winner-takes-all outcome. We think that means encouraging, protecting, and preserving sharp-edged competition both from innovative independent players but also, importantly, between the largest incumbents.

In the update report, we identify 3 key interlinked risks to fair, open and effective competition:

-

first, that firms that control critical inputs for developing foundation models may restrict access to them to shield themselves from competition

-

second, that powerful incumbents could exploit their positions in consumer or business facing markets to distort choice in foundation model services and restrict competition in foundation model deployment

-

and third, that partnerships involving key players could exacerbate existing positions of market power through the value chain

We set out how each of these would be mitigated by our proposed principles, as well as what action we are taking now, and considering taking in the near future, to address these concerns. We make clear that we are carefully considering how to apply the full range of our legal powers most effectively, both existing measures like market investigations and merger review, but also new anticipated powers to promote and safeguard competition in digital markets through the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill, which is currently going through Parliament in the UK.

As we did in our first report, we urge firms to align their business practices with our proposed principles; and to work with us to help shape positive market outcomes.

To conclude, the essential challenge we face is how to harness this immensely exciting technology for the benefit of all, while safeguarding against potential exploitation of market power and unintended consequences. Making sure we are not sleepwalking into systemic change which could harm business users and end consumers and stunt the benefits that should flow from fair, open and effective competition. For the CMA, it is a fine balance that requires objective and evidence-based assessment, vigilance, foresight, and a steadfast commitment to acting in the interests of those we serve. There is more to come, but I will leave it there for now.

Thank you.

Can you talk us through the 3 key risks you identified in a little more detail and what action you are taking or proposing to take?

Our first concern is that large firms controlling critical inputs for foundation model development may have both the ability and incentive to restrict access to those inputs to shield themselves from competition.

For example, materially restricting access to key inputs like compute, data or expertise would prevent challengers from building effective, competitive models. It might also reinforce incumbents’ positions in related markets like search and productivity software, by making it harder for potential rivals there to develop or deploy capable models that could provide the building blocks for a next generation competitive alternative to those services.

There is possibly a degree of inevitability to some of the concentration of control over key inputs we are seeing. But that is where our principles are crucial. Notably our Access principle - to ensure independent foundation model developers can get access to key inputs without undue restriction – and our Diversity principle to safeguard the viability of independent model development. In that context we would also be concerned to see further concentration of control over key inputs.

I’ll say a word here specifically about what have recently been described as the AI ‘talent wars’. Of course, it is open to businesses to hire talent in a competitive market. But specialist expertise is one of the key inputs we’ve identified for building competitive models. It would clearly be damaging to competition if the battle for talent amongst these deep-pocketed companies resulted, in practice, in it becoming impossible for challengers to hire and retain the limited pool of people capable of building and developing them. We also need to be vigilant where arrangements related to talent result in an outcome which may be similar to a full-scale acquisition of a company.

In terms of action, we are taking now to address this first risk, I’ll give you 3 examples:

-

first, as part of our ongoing Cloud Market Investigation, we are assessing the market position of the main cloud service providers and the investigation will include a forward-looking assessment of the potential impact of foundation models on how competition works in the provision of cloud services

-

second, we are examining Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI to understand how it could affect competition in various parts of the ecosystem

-

and third, we are examining the competitive landscape in AI accelerator chips and the impact on the foundation model value chain

We will also evaluate developments in foundation model markets as part of our consideration of which digital activities to prioritise for investigation under the new Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill. This might, for example, consider key inputs like compute, including via cloud services. We haven’t yet taken any provisional decisions on prioritisation for the new regime, but any designation would be subject to a prior investigation and would, of course, take into account findings from related work, such as market investigations.

The second risk is that powerful incumbents could exploit their positions in consumer or business facing markets to restrict competition in model deployment and distort choice in foundation model services.

We must be realistic that the choices of people and businesses will very likely be shaped by current familiarity or preference for digital products and platforms, like mobile, search engines, productivity software or cloud-based developer platforms. So, firms that already control these ecosystems could wield significant power over model deployment and choice of services.

Again, our Diversity principle is obviously vital here. So too our Choice principle, which is designed to mitigate against lock-in. And our Fair-Dealing principle, which supports the best products winning out, unimpeded by anti-competitive practices.

There are several potential areas here to consider as part of our prioritisation for investigation under the DMCC Bill. These could include digital activities that serve as critical access points or routes to market for foundation model deployment, like mobile ecosystems, as well as search and productivity software.

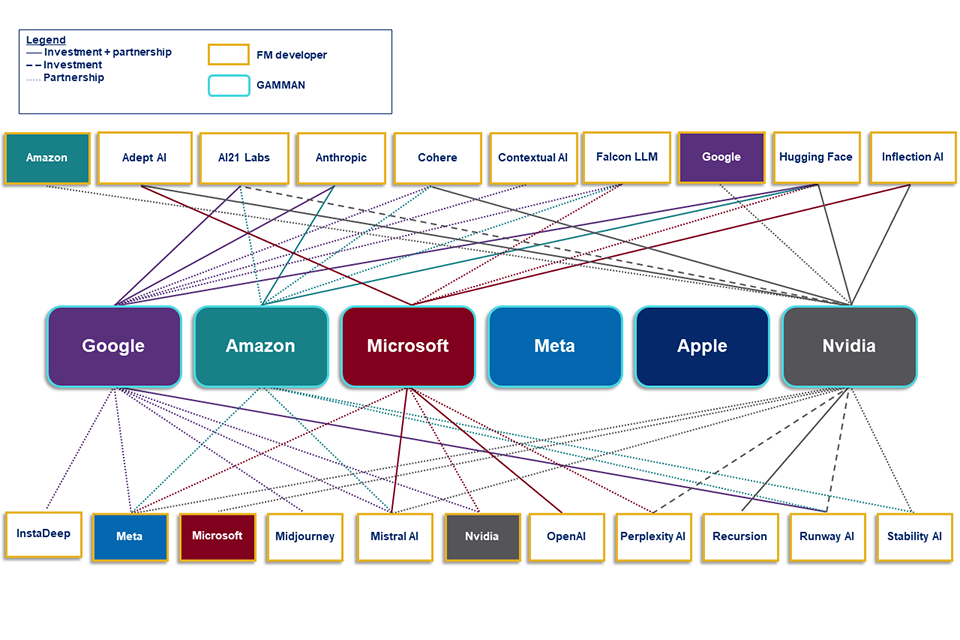

Turning to the third risk that partnerships involving key players could reinforce or extend existing positions of market power through the value chain.

We identify an interconnected web of over 90 partnerships and strategic investments in the foundation models value chain involving the same firms: Google, Apple, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon and Nvidia - the leading supplier of AI accelerator chips. A quick look at this chart illustrates the point.

Figure 3: Key GAMMAN- FM Developer Relationships[Footnote 2]

A description of this image can be found in the alt text section.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, these are often also the firms with the strongest positions in relation to the key inputs, as well as access points or routes to market, for foundation models. To be clear, we are aware that such partnerships typically form part of the development and investment ecosystem in the technology space – and indeed may be an essential ingredient for the success of independent developers. We understand that they can potentially bring pro-competitive benefits. And, of course, each must be assessed on its individual facts and merits. However, in combination with the 2 risks already mentioned, we are concerned that this interconnectedness could enable firms with power in existing digital markets to exert control and influence over multiple parts of the foundation model value chain to entrench these existing positions, or to extend into adjacent markets.

So, we believe the application of our principles is essential here to safeguarding fair, open and effective competition. Our ‘Access’, ‘Diversity’ and ‘Choice’ principles set out that powerful partnerships and integrated firms should not reduce others’ ability to compete. And our ‘Fair Dealing’ principle makes it clear that vertical integration and partnerships should not be used to insulate firms from competition.

How are we acting on these today? As you would expect, we are keeping a very close watch on these current and emerging partnerships, especially where they relate to important inputs and involve firms with strong positions in their respective markets and models with leading capabilities.

One way we are doing that is to step up our use of merger control, so that we can assess whether, and in what circumstances, these kinds of arrangements fall within the merger rules and whether they raise competition concerns. Some of these arrangements are quite complex and opaque, meaning we may not have sufficient information to assess this risk without using our merger control powers to build that understanding. It may be that some arrangements falling outside the merger rules are problematic, even if not ultimately remediable through merger control. They may even have been structured by the parties to seek to avoid the scope of merger rules. Equally some arrangements may not give rise to competition concerns.

By stepping up our merger review, we hope to gain more clarity over which types of partnerships and arrangements may fall within the merger rules, and under what circumstances competition concerns may arise - and that clarity will also benefit the businesses themselves.

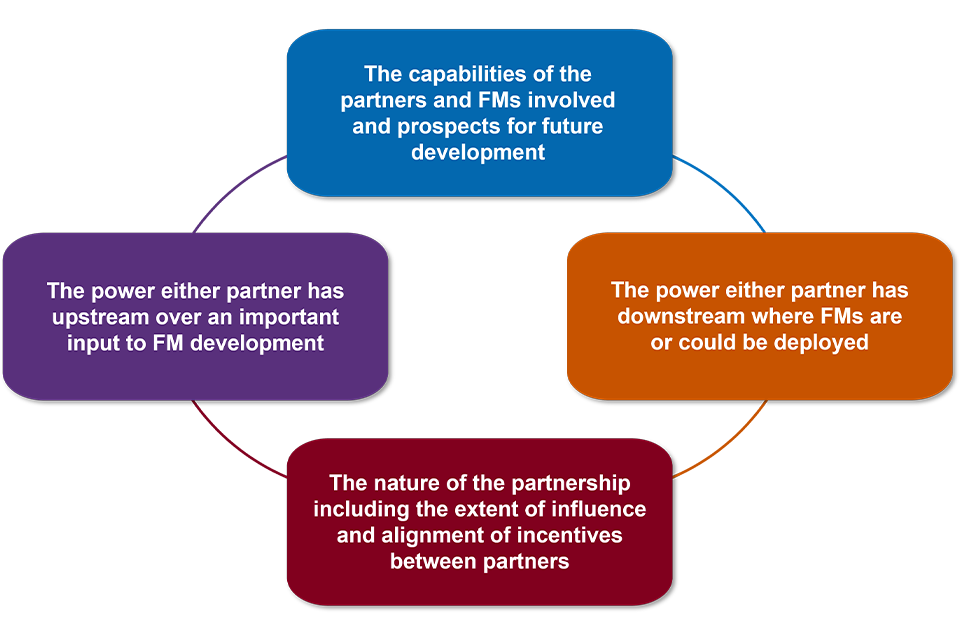

In our update report we will also set out some indicative factors which may drive greater concern, with a focus on partnerships that involve some of these features as reflected in this chart.

Figue 4: Factors the CMA may consider when assessing the potential impact of partnerships

A description of this image can be found in the alt text section.

Of course, we expect these indicative factors to evolve as we gain more experience from our various reviews of current and future arrangements.

It sounds like your conclusion is that there is a real risk to competition? But what about other policy considerations like consumer protection, safety, and security?

Based on what we know today, the risks I’ve described are real, yes. I think it’s fair to say that when we started this work, we were curious. Now, with a deeper understanding and watching developments very closely, we have real concerns.

But we also have an opportunity to act now, hopefully with the constructive engagement of industry stakeholders. So, we are committed to applying the principles we have developed, and to using all legal powers at our disposal - now and in the near future – to ensure that this transformational and structurally critical technology delivers on its promise.

You asked about other policy areas and of course the CMA’s remit also extends to consumer protection. I don’t have time to go into that aspect of our report today, but we do also have concerns that AI-powered products and services have significant scope to facilitate unfair consumer practices and our ‘Transparency’ and ‘Accountability’ principles are geared toward preventing these harms.

We also recognise concerns around other important policy areas like safety and security. Although these are outside our direct remit, I do think there are important connections to be made with competition and consumer protection, which is why it’s important to be part of those broader policy conversations. For example, given what we know about the specific risks of AI in terms of automating and industrialising the spread of harms where things go wrong, I am inclined to come back again to the importance of plurality of models, with appropriate safeguards, as a helpful mitigation here. And, while it’s extremely positive to see standards and rules around AI safety developing around the world, we do need to make sure that whatever emerges from that work - in which the largest tech players are heavily involved - does not act as a blocker for innovators and challengers. We talked about this in our first report and will do so again in our update report.

Footnotes

Footnote 1: This figure is illustrative and non-exhaustive – it is not representative of all possible presence of these firms across the FM value chain nor the deployment markets in which they are active.

Footnote 2: The relationships mapped here show a partnership and/or investment between a GAMMAN firm and an FM developer partner, where the relationship involves the latter’s development or provision of FMs. That FM developer could also be a GAMMAN firm. This is not an exhaustive list of the partnerships which exist in this space. See the report for a map of further partnerships and for notes to this diagram.

Alt text

Figure 1: This figure shows which of the GAMMA firms are operating in each of the following parts of the FM value chain:

(1) Compute: Amazon, Google and Microsoft

(2) Data: Google, Meta and Microsoft

(3) FM development: Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta and Microsoft

(4) FM partnerships and agreements: Amazon, Google and Microsoft

(5) FM release: Amazon, Google and Microsoft

(6) Search: Google and Microsoft

(7) Social media: Meta

(8) Mobile ecosystems: Apple and Google

(9) PC operating systems and productivity software: Apple, Google and Microsoft.

Figure 2: This schematic diagram indicates how powerful incumbent technology firms could profoundly shape FM-related markets in their own interests:

-

on the left, it shows control of critical inputs for FM development (such as compute and data), which could allow firms to restrict access to such inputs, and is a driver for the formation of influential partnerships with FM players

-

on the right, it shows control of key access points and routes to market for FM deployment (such as platforms and digital products), which could allow firms to restrict choice of FM services downstream (including self-preferencing their own services), and is a driver for the formation of influential partnerships with FM players

-

the restriction of access to inputs, restriction of choice of FM services, and the formation of partnerships are shown leading to outcomes whereby the incumbent firms could protect their existing positions from disruption and/or extend market power into new markets

-

finally, there is a potential feedback loop from these outcomes back up to the control of inputs and access points

Figure 3: This figure maps relationships between the GAMMAN firms (Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, Apple and Nvidia) and FM developers. Different styles of lines are used to indicate where a relationship is an investment, a partnership, or an investment plus partnership, and the colour of line corresponds to the GAMMAN firm.

Figure 4: This figure shows the four factors the CMA may consider when assessing the potential impact of partnerships:

(1) The power either partner has upstream over an important input to FM development

(2) The capabilities of the partners and FMs involved and prospects for future development

(3) The power either partner has downstream where FMs are or could be deployed

(4) The nature of the partnership including the extent of influence and alignment of incentives between partners