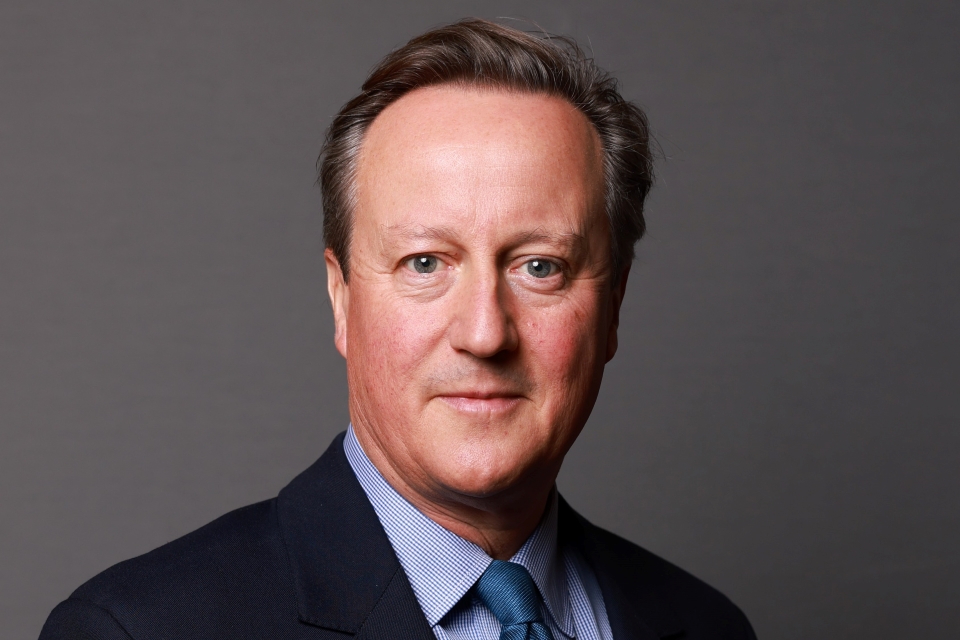

Prime Minister's speech on modern public service

A transcript of a speech on modern public service by Prime Minister David Cameron on 17 January 2011.

A transcript of a speech on modern public service by Prime Minister David Cameron on 17 January 2011:

I start this year incredibly optimistic about what our country can achieve.

Yes, cuts in spending will be felt - and yes, they will be difficult but they are absolutely vital in restoring the credibility and confidence that will mean jobs and growth in the future.

But the scale of this coalition’s ambitions for Britain goes beyond simply fixing our economy.

I want one of the great achievements of this Government to be the complete modernisation of our public services.

I want us to make our schools and hospitals among the best in the world.

To open them up and make them competitive, more local and more transparent.

To give more choice to those who use our public services and more freedom to the professionals who deliver them.

I don’t want anyone to doubt how important this is to me.

My passion about this is both personal and political.

Personal because I’ve experienced, first hand, how dedicated, how professional, how compassionate our best public servants are.

The doctors who cared for my eldest son, the maternity nurses who welcomed my youngest daughter into the world, the teachers who are currently inspiring my children all of them have touched my life, and the life of my family, in an extraordinary way and I want to do right by them.

And this is a political passion - and priority - of mine too.

I believe that Britain can be one of the great success stories of the new decade.

We have the creativity and the energy, the language and the global position, the relationships abroad and the stability at home, to make the most of the opportunities that globalisation is bringing.

One of the keys to success for countries like ours will be the performance of our public services.

We must champion excellence - and stop the slide against our competitors.

In Shanghai the average child is two years ahead of a child here.

In Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Austria and Poland you are less likely to die once admitted into hospital after a heart attack.

Put simply: we can’t be a modern success story unless we have modern, successful public services.

And this is not an alternative to dealing with our debts - it’s a key part of it.

Like every other western industrialised nation, we won’t sustainably live within our means with unreformed public services and outdated welfare systems.

We have to be completely focused on getting more for less in our public services.

And this argument about modernisation is not just a hard headed one about Britain’s place in the world or value for money - it is deeply progressive.

We should be clear about where our public services have succeeded in making our country fairer and more equal over the years but we should be just as frank about where they have failed.

And the truth is that we won’t eliminate the scars of deep poverty and huge inequalities in our country if we go on with services as they operate today.

But quite apart from all these practical arguments for modernisation, there’s what I’d call the people argument.

If politics is about anything, it’s about focusing on those things people really care about - and making them better.

There is nothing more important to people than the education their child gets, the care their parent receives, or the safety of the streets they walk down.

And I share the burning impatience of so many who are frustrated that, in too many instances, we are asked to settle for second best.

I passionately believe that it does not have to be this way.

So we are determined to modernise our public services and make them better for everyone.

Now, I predict some eyes are rolling.

You feel you’ve heard this all before - and yes, you have.

Many politicians have stood on platforms like this stating similar ambitions but, all too often, despite minor improvements here or there, nothing really fundamental changes.

Added to that, you’ve got some serious concerns about the conditions we’re working in and the changes we plan.

So today, I want to answer, as directly as I can, the questions you have.

First, how can we modernise public services when there is so little money?

Second, why do we believe there is a real prospect of our succeeding in modernising public services when so many others have not?

Third, won’t there be losers from the changes we make?

And fourth, do you have to make all these changes so fast, so soon?

Let me take each in turn.

First, how can we modernise public services when there is so little money?

To begin with, we need some perspective.

Of course, there are things government does today that it will stop doing.

Of course some decisions will be difficult and involve difficulties.

But when we’re done with these cuts, spending on public services will actually still be at the same level as it was in 2006.

We will still be spending 41 percent of our GDP on the public sector.

And beyond these headline figures, let’s remember:

We will still be spending £5,000 a year on educating each child in our country with even more money for those from the poorest backgrounds.

That’s the same as Germany and more than France.

There will still be as many police officers in the Metropolitan Police as in New York.

And, because we are increasing the NHS budget, health spending will be up at the European average.

So it’s just not true to say that the spending taps are being turned off.

The money will be there and we will spend it wisely.

And let’s also remember this.

There are some improvements we need to make which don’t necessarily cost money.

Enforcing discipline in our schools - this won’t cost money.

Getting pupils to take a wider range of core academic GSCEs - this won’t cost money.

A commitment to rigour and standards in the exam system - this won’t cost money.

But there’s a more important argument I want to make about money and our public services.

Every year without modernisation the costs of our public services escalate.

Demand rises, the chains of commands can grow, costs may go up, inefficiencies become more entrenched.

Take the NHS.

We face enormous pressures on demand - driven by an ageing population, obesity and alcohol abuse and the rise of infectious diseases like TB.

And at the same time, we have rising pressures on cost with expensive new drugs and technological innovations like genetics, nanotechnology and robotics all being integrated into the work of healthcare.

Pretending that there is some “easy option” of sticking with the status quo and hoping that a little bit of extra money will smooth over the challenges is a complete fiction.

We need modernisation - on both sides of the equation.

Modernisation to do something about the demand for healthcare - which is about public health.

And modernisation to make the supply of healthcare more efficient - which is about opening up the system, being competitive and cutting out waste and bureaucracy.

Put another way: it’s not that we can’t afford to modernise; it’s that we can’t afford not to modernise.

The second question is this: why will this government succeed with modernising public services when so many others have failed?

Indeed, given this is a coalition, how will we even agree on what the change is that we need, let alone deliver it?

Yes, we have differences of opinion.

But politics should be no different from the rest of life, where rational people find a way of overcoming their disagreements.

Indeed, I’ve found that instead of arguing about tribal dividing lines or sticking to long cherished positions what we do is have a proper discussion about what really works.

And as you can see with radical policies from the Universal Credit in welfare, to free schools in education or strengthening our universities the policies that result can be more wide-ranging and more effective than when you’re working on your own.

There’s another reason why I believe this Government can really succeed.

It’s because we have tried really hard to learn the lessons of the past.

We recognise the good things previous governments did - and we’re going to do more of them.

But we also understand where they failed - and we are going to avoid making the same mistakes.

I believe previous Conservative Governments had some really good ideas about introducing choice and competition to health and education - so people were in the driving seat.

But there was insufficient respect for the ethos of public services - and public service.

The impression was given that there was a clear dividing line running through our economy with the wealth creators of the private sector on one side paying for the wealth consumers of the public sector on the other.

This analysis was - and still is - much too simplistic.

Public sector employees don’t just provide a great public service - they contribute directly to wealth creation.

It’s not just that, for instance, teachers nurture the human capital that fuels enterprise or that nurses help keep the nation healthy and working.

Parts of the public sector help generate innovation and wealth more directly like our teaching hospitals and universities which, can be one of the great wealth creating engines of the 21st century, knowledge based economy.

All this must be recognised.

In many ways, under the last Government, the problem was the opposite.

There was tremendous respect for the ethos of public services, but not enough emphasis on opening them up.

For sure, Tony Blair introduced academies and increased independent provision in the NHS.

But he did so while maintaining a whole architecture of bureaucracy and targets and significantly understating the valuable role of charities and the voluntary sector.

What’s more, when he did to try to be bolder he got blocked by - and too often surrendered to - vested interests.

Foundation hospitals could only go ahead with endless restrictions on what they could do.

School reform could only go at a pace that the trade unions - and Gordon Brown -could tolerate.

Reading his intriguing memoir over the summer, I was struck by how many times he himself admits that opportunities were lost and Labour should have ‘pushed further and faster on reform’.

I think the lessons from the past are clear.

The right were guilty of focusing too much on markets.

The left were guilty of focusing too much on the state.

Both forgot that space in between - society.

And having watched, absorbed and learned from all this, I believe this coalition has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to transform our public services.

From schools to the NHS, policing and prisons, we have developed a clear plan for modernisation based on a common approach.

A Big Society approach, which empowers not only services users, but professionals that strengthens not only existing providers, but new ones in the private and voluntary sectors too.

Our starting point is huge respect for the ethos of our public services - and a commitment to advance it.

Free to all who need it, universal coverage, impartiality - these are principles must never come under threat.

And we will also liberate the people who work in our public services.

We have extraordinary talent in our public services, from surgeons who lead the world in open-heart surgery, to teachers driven by a calling to transform the lives of our children and we want to give them the freedom to get on with their job.

So we are taking apart the targets, the inspection regimes, the thickets of guidance that smother doctors, nurses, teachers and police officers.

For example, one obstacle teachers face in restoring discipline is that they have to give - in writing - 24 hours notice for a detention.

We’re getting rid of that rule and giving teachers much greater control over order in their classroom.

But freedom for professionals isn’t just about getting rid of the bureaucracy, it’s about actively empowering them to deliver the best service.

That’s what we are doing.

So there are new powers to enable public sector workers to take ownership of their organisations and form mutuals and co-operatives.

New powers for new and existing providers in welfare, drug rehabilitation, the reduction of re-offending and early years support to focus on the needs of users with an assurance from us to pay them by the results they achieve.

No interference from on-high - telling them what to do.

Just the open tendering of contracts, complete professional freedom and a commitment to encouraging innovation combined with proper rewards for the good work they do.

There are also new powers for schools - including for the first time special schools - to turn into academies with the freedom to enforce rigorous discipline policies, pay more for good staff and develop excellent extra-curricular activities.

And new powers for GPs, who can join together in consortia, take control of NHS budgets and directly commission services for their patients.

People said there would be no appetite for this.

But let me tell you today the enthusiasm of heads has meant that we have created as many academies in seven months as Labour managed in seven years and far from fearing new commissioning arrangements, over 140 GP-led consortia have now come forward, covering over half the country.

But this freedom does not mean a free for all without proper accountability or a focus on results.

Far from it.

In return for this freedom from central control, professionals will have someone new to answer to - people.

We are giving them the power to shape and design the public services they use.

So we are spreading choice, saying to any parent or patient: you can choose where your child gets sent to school or where to get treated and we’ll back that decision with state money.

We are injecting competition, saying to the private sector, community organisations, social enterprises and charities: come in and deliver great public services.

Already people are answering that call - not least in education - where the first free schools will open in September.

I myself met the inspirational parents and local leaders who are going to set up the first of these in Clare in Suffolk.

A small community in a rural area where children face long commutes will now have a high quality school on its doorstep.

And next week, in our Education Bill, we will go further.

For the first time, charities, universities, businesses, teachers and groups of parents will be allowed to establish their own academies where there is a lack of suitable education for 16-19 year olds.

Based on the same principles that underpin our Free School programme, this will widen the range of options available to young people and encouraging them to continue in education beyond their GCSEs.

We are also bringing real democratic legitimacy to our public services too.

On the way are new elected police and crime commissioners that local people can vote in and if these commissioners don’t deliver on their promises they will be answerable to the public at the ballot box.

At the same time as doing all this, we’re also going to make everything as transparent as possible.

So people will not only know where the money is spent in our public services but how well that money is spent too - on health outcomes, schools results and crime figures.

What I have described is a clear, consistent, comprehensive plan that covers all public services.

And, returning to my point about the coalition, I believe it is a programme that Conservatives and Liberal Democrats can give their wholehearted support.

Revere, cherish and reward an ethos of public service.

Free professionals from top down control and bureaucracy.

Give choice to the user.

Encourage competition between the suppliers.

Pay by results wherever appropriate.

Publish information available everywhere you can.

Make public service professionals answer to people, rather than the government machine.

Services that are more local, more accountable and more personal where people are the drivers, not passengers which call on every part of society - from churches to charities, businesses to community organisations - to come in and make a difference.

It really is a complete change in the way our public services are run.

From top-down bureaucracy to bottom-up innovation.

From closed markets to open systems.

From big government to big society.

Even if people accept that we are well-placed to modernise public services they have another question: won’t the changes we make create losers?

They worry that our approach is a kind of public service version of a laissez-faire economic policy where winners are created at the expense of those who get left behind.

I believe these worries are profoundly misguided - and I want to explain why.

We are not proposing laissez-faire.

The state has a hugely important responsibility to ensure clear, basic standards are met, the rights of users are maintained and independent inspection is carried out in our public services and we are in no way abrogating that.

Indeed, in education we have raised targets for school performance so that under-performing schools are turned around more quickly.

And yes, added to that, I also believe extra resources must be directed to those who are most disadvantaged.

That’s why for the first time ever there will be a specific payment to schools - a pupil premium - for every child entitled to free school meals.

But isn’t the real point this?

If we have learnt anything about public service reform in the past few decades, it’s that simply setting standards and issuing diktats from Whitehall doesn’t mean they actually happen.

We do need structural changes - not just edicts about standards.

While one-size-fits-all state provision played a large role in reducing inequalities in the past, in recent years it has failed to do so.

Indeed, arguably it has actually deepened the disparities between regions, classes and racial groups in our society.

The evidence is clear.

Health inequalities in 21st century Britain are as wide as they were in Victorian times.

Today, a quarter of all children - overwhelmingly from the most disadvantaged families - don’t get a single A or B at GSCE.

One of the reasons for this is also clear.

Exercising choice to escape poor service is available to the richest, who can either opt-out and go private or to the middle classes, who can move house to get into the best schools but the poorest have to take what they’re given.

So the approach of relying on Whitehall diktats rather than real structural change has failed the very people it was trying to protect.

And worst of all, those who lost out are powerless to do anything about it.

Our structural changes can help them.

Just consider the evidence of the most recent years, in those areas where principles of competition, choice and greater independence for institutions have been introduced.

Some of our Foundation hospitals are bringing the very best care to the people who need it most.

City Technology Colleges and Academies are transforming education results in some of our poorest communities.

These structural breakthroughs have given new opportunity to those in the poorest areas, who have been let down by the old system.

And the next great poverty-busting structural change we need - the expansion of University Technical Schools - will do the same, offering first-class technical skills to those turned off by purely academic study.

There’s a simple logic to all this: with more freedom and openness comes more creativity and innovation.

And with competition comes the pressure to keep up with the best.

So for us inequality is no longer simply the static symbol of unfairness that it is today but rather a potent call to arms - a kick-start, if you like, to the actual mechanism that helps drive the delivery of better services for everyone.

All too often what the people who criticise our plans are demanding is a race to the bottom where the cause of fairness is used malevolently to prevent any innovation or progress that could allow one child or one school to do better than another.

What we propose is a race to the top where experimentation and innovation in one place gives everyone the chance to learn and benefit from each other.

A real race for excellence.

Improvements across the board.

Not a black white world of winners and losers - but a world where everyone has the opportunity to make the most of their potential.

The fourth question people ask is this: do we have to make all these changes so fast, so soon?

They accept the need for change.

But they are concerned about the pace.

They fear we are doing too much at once.

Of course, these changes have to be carefully worked through.

And that’s exactly what we have done through our years of preparation in Opposition - and we will continue to do so every day in Government.

But remember this.

Every year we delay, every year without improving our schools is another year of children let down another year our health outcomes lag behind the rest of Europe another year that trust and confidence in law and order erodes.

These reforms aren’t about theory or ideology - they are about people’s lives.

Your lives, the lives of the people you and I care most about our children, our families and our friends.

So I have to say to people: if not now, then when?

We should not put this off any longer.

And here’s another case for urgency.

The longer you leave things, the greater the institutional inertia against change becomes.

Tony Blair as good as admits that he wasted his first term, flogging the horse of centralised control.

Is it any surprise that when he came to real modernisation - an agenda that promoted choice and competition - the government machine was sceptical?

Was this just another fad that would be reversed?

Or was he serious?

We have set our stall out from the beginning, leaving no one in doubt: this coalition is serious about modernisation.

This week, our Health Bill will be put before Parliament.

Next week, our Education Bill will be put forward.

Next month, we are publishing a White Paper on the next steps for modernisation.

Eight months in and you can see we are simply not wasting a moment in delivering first-class, world-class, public services in our country.

Let me end with a message for the people these reforms will affect the most - those who work in our public services, and those who use them.

To our public sector workers:

No one believes that the budget deficit is the fault of public sector workers.

Responsibility lies squarely with ministers in the last government who allowed spending to run out of control.

And as we take the tough but necessary steps to deal with the deficit, our first priority is to protect front line services, and to protect jobs in the public services.

We won’t be able to avoid job losses entirely. That would be unrealistic.

But by taking swift and radical action to cut the overhead costs of government we gave ourselves the best chance there is to protect jobs.

By squeezing what we pay to suppliers.

By cutting spend on wasteful IT projects.

By simply dropping some projects that were never going to deliver value.

By our moratorium on advertising, marketing and consultants.

All of these tough and unglamorous measures will save in the region of £3billion just in this financial year alone.

Every pound saved this way helps save jobs and services.

At the same time, we want the jobs of the future in public services to be more fulfilling.

Empowering you on the front line.

Freeing you from top down micro-management and targetry.

Supporting groups of workers who want to form mutuals and cooperatives to deliver services themselves.

Liberating the hidden army of public service entrepreneurs, deeply seized with the public service ethos, but who itch to innovate and drive improvement themselves.

I know there’s a hunger for this.

When we launched our public sector spending challenge in the summer, some were cynical.

Yet 65,000 public sector workers submitted ideas for how money could be saved without damaging the quality of services.

There is huge pent-up frustration among so many public sector workers who see how things could be different but can’t make it happen.

The modernisation I’ve outlined today will give you that power.

And to the country at large, let me say this:

Everything I have spoken about today - the ideas that guide modernisation, the plans that shape it - these are not the final destination.

The final destination, for us, is not more freedom for professionals, or more choice for you, or more competition in our public services.

It’s those things which are more difficult to measure but you just know it when you feel it, when you see it.

The sense that first class healthcare is available to all, regardless of their wealth.

That every child grows up with the doors of opportunity open to them, where birth is never a barrier, because they have a great school down their road.

That every citizen feels safe in their neighbourhood, with trust and confidence restored to law and order.

This goes right to heart of what we stand for.

The quality of care we offer in our health service is a measure of the country we are.

The quality of education we offer our children is a measure of the country we can become.

As a nation we have great pride in our history of public services in the creation of the NHS and the principles of state-funded health care and education for all.

And it is the mission of this coalition government to renew the promise of opportunity, fairness and excellence for all in our public services today.