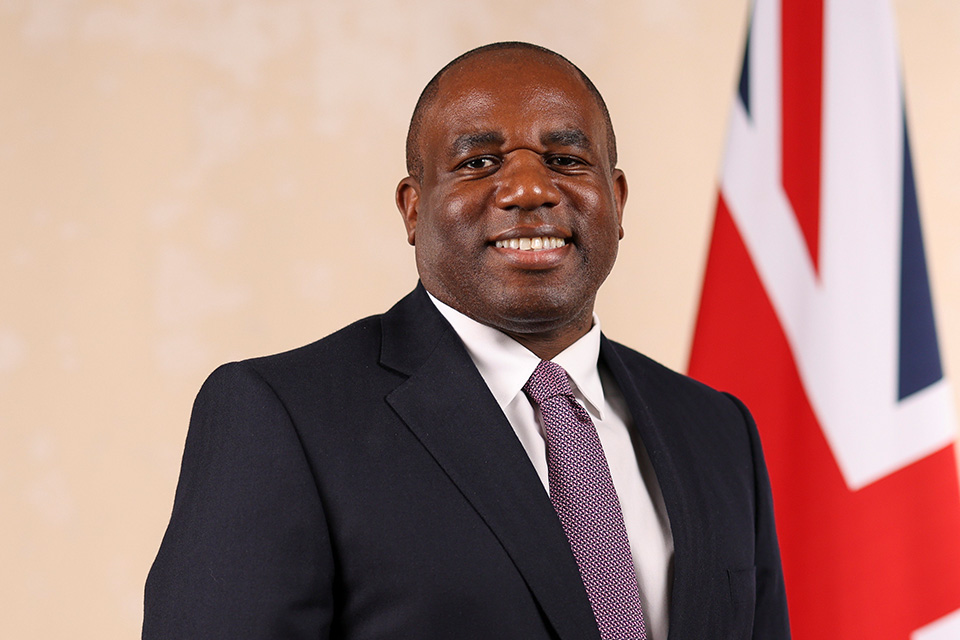

David Lammy's speech to London Councils

David Lammy's speech to London Councils.

Introduction

Thank you very for having me here today. We meet at a time of change. This city has a new Mayor, with a different set of priorities. The country has a new Prime Minister. The Home Office and the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) both have new Secretaries of State.

That will mean change in Westminster and Whitehall, beyond the obvious question of our relationship with the European Union.

We don’t know precisely what that change will look like, but we do know this: one of the first things Theresa May said when she launched her leadership bid, was that:

If you’re black, you’re treated more harshly by the criminal justice system than if you’re white.

Now as a Labour politician you would not expect me to agree with everything the new Prime Minister did during her time as Home Secretary.

But I do believe she deserves real credit for her reforms to stop and search.

No-one says we have cracked the issue completely. But progress is being made and that is not an accident.

So when she says she is concerned about our criminal justice system, I think it is right that we take the Prime Minister at her word.

Disproportionality

The last Prime Minister, David Cameron, also identified this as an area of concern.

As many of you will be aware, in January he asked me to conduct an independent review into the disproportionate representation of ethnic minorities in the criminal justice system.

It is a long-standing issue that has risen to prominence again in this country, not least through the work of Lola Young and the commission she led on the subject.

Ethnic minorities currently make up over a quarter of prisoners – compared to 14% of the wider population of England and Wales. That figure shocks most people.

But it looks positively rosy when you set it alongside the youth prison population. Of those whose ethnicity we know about, over 40% of young people in secure institutions come from ethnic minority backgrounds.

And when you look more closely at the figures you learn something else. Over the last ten years the number of young people in these institutions has fallen dramatically. Ten years ago there were around 2,800 young people in youth custody. Today the figure is around 900.

There was a deliberate policy decision to incarcerate fewer young people and it has made a real difference. But during that time, the proportion of ethnic minorities in the youth prison population has risen, not fallen. Ten years ago it was 27% of the youth prison population, today it is over 40%.

I don’t need to tell the people in this room that there are many, many reasons for this. Not all the causes lie in the criminal justice system and not all the answers do either.

It is a story of deep social and economic currents that see young men and women swept up in trouble. I spent a year writing a book about some of these problems following the London riots in 2011.

But it is not just current and former prime ministers who are concerned with the workings of our criminal justice system itself.

There are still those in ethnic minority communities who believe they do not get a fair deal, or that the system is insufficiently geared towards their needs. My review focuses on those concerns. It examines the way the criminal justice system works, from the role of the Crown Prosecution Service in charging decisions, to the decisions of juries and judges in the courts, the way people are treated in prisons and secure youth institutions, to the efforts of the probation service and rehabilitation in the community.

The review covers both adults and young people – and, of course, both men and women. And it adopts a broad, inclusive definition of ‘ethnic minority’.

So I examine the needs of minority groups who are white, including groups like Gypsies and Travellers, who are hugely overrepresented in the system.

It takes into account religion and well as race, particularly given the sharp rise in the Muslim prison population over the last ten years.

That is a huge amount to cover in 12 months, before I report back to the new Prime Minister in spring next year.

But today I want to focus my remarks on one particular issue that is pertinent to London, relevant to people from ethnic minority backgrounds – and which has been raised with me on numerous occasions since I began this review.

That issue is the role of gangs and the response of the criminal justice system to them.

Gangs

My starting point for this is that gangs remain a major, major problem for the UK and especially in London.

Government figures suggest that gang members carry out half of all shootings in this city and more than a fifth of all serious violence.

Just this month a young man, aged just 17, was stabbed to death in Notting Hill, in broad daylight, having reportedly been chased through the streets by a gang of youths.

The victim was a popular boy, studying for his A-Levels.

Two boys, aged 15 and 16, have been charged with murder and possession of an offensive weapon. This is senseless, heart-breaking violence. It is robbing parents of their children. It is robbing children of their futures.

So, I understand just how serious the problem is.

I recognise, also, that many of the victims of gang-related crime come from ethnic minority backgrounds.

But the concern I have heard – repeatedly I must say – is that young people from ethnic minority backgrounds are being tagged with the ‘gang’ label in ways they do not feel is justified. And that this tag can have real consequences for the way the criminal justice system deals with those individuals. The context for this is that, in response to the public concern over gang violence, the Metropolitan Police have developed a Gangs Matrix – a database of suspected gang members in London.

Figures published by the Met in 2014, following freedom of information requests, showed that of the 3,422 people listed on their Gangs Matrix, 79% were black and a further 9% were from other ethnic minority backgrounds.

Gangs and the Criminal Justice System

My concern is around how this data is used by the criminal justice system – and how it is verified. For example, the Gangs Matrix features information provided by the police to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) at the point when the CPS makes charging decisions.

The inclusion of this information suggests that prosecutors regard it as pertinent to whether defendants are charged, or what they are charged with.

If cases make it as far as court, the Gangs Matrix could than used by the prosecution in cases involving Joint Enterprise. It is deployed to substantiate claims that individuals are part of a gang and therefore played their part in a crime.

Joint Enterprise is, of course, itself the subject of a High Court ruling at the moment – and that is something I am watching very carefully indeed.

But, for now, my point is that having your name on the Gangs Matrix can count against you when you go before a jury of your peers.

It is also the case that involvement in a gang can be an aggravating factor when it comes to sentencing decisions made by judges.

In robbery cases, for example, sentencing guidelines published in 2006 included, ‘offenders operating in groups or gangs’ as an aggravating factor.

The updated guidance published in January this year identifies group offending as an aggravating factor.

Again, having your name associated with a gang can contribute towards harsher treatment.

Should an individual be sentenced to prison, Governors will certainly want to know if their new inmate is – or was – a member of a gang.

This can be for very good reason – for example, to protect the individual against violence from other inmates.

But it can also have consequences for the perceived riskiness of an individual – for example when judgements are made about suitability for work experience on day release.

Then, when an individual is released from custody, it is expected that probation services understand the circumstances that led to their original offence.

Probation officers and youth offending teams are therefore informed if an individual is known to be part of a gang. This information affects decision about resettlement, including the list of reasons for which they might be recalled to prison after their release.

Information first recorded on the Gangs Matrix informs this process.

Finally, suspected gang membership can also play a role in the extent to which ex-offenders come into contact with the police on their release, which is relevant, of course, to re-conviction rates.

This is because the Matrix informs operational decisions taken by the police.

The guidance on stop and search indicates that whilst an individual’s past criminal history does not constitute grounds for stopping and searching them, suspected membership of a gang can be taken into account.

Evidence of gang membership can include things like wearing ‘a distinctive item of clothing or other means of identification in order to identify themselves as members of that group or gang’.

We have, therefore, a journey through the system in which suspected gang membership can affect decisions at each turn, from charging to conviction, to sentencing, to treatment in prison and rehabilitation in the community.

And we have the Gangs Matrix as the source of much of the information used by other actors in the justice system.

The question I intend to examine through my review, is how reliable this information is and how closely the various parts of the criminal justice system scrutinise it.

Prisoners I have spoken to in both adult prisons and youth offending institutions have often been frank about their involvement in criminality.

But the same people have also often been insistent that they were mislabelled as ‘gang members’ by the police and then subsequently by the rest of the justice system.

One parent told me about the experience of his two adopted children – one black, one white. Both had found themselves in trouble and made their way through the criminal justice system as a result.

But it was the black child who had wrongly been tagged with the label of ‘gang member’ and the label had stuck.

The parent and his adopted son had no idea how to remove the label – and his name from the Gang Matrix.

This reflects research done by Manchester Met University on the Manchester Police gang database. Academics given access to the database were told by police officers that the list included not just individuals known to be gang members, but also those judged to be ‘at risk’ of gang involvement. Further investigation revealed that 40 of the 172 individuals on the Manchester database had no previous convictions.

Of all those on the list, 89% were from ethnic minority backgrounds.

The question is not just the decisions the police make, but the way the rest of the justice system uses this kind of information.

One member of a youth offending team told me that her team would routinely make decisions based on the information they were given about gang membership.

Decisions, she said, were being made without challenging where the information came from, or whether it was reliable and up-to-date.

My concern is how widespread this practice and these experiences are.

Where next

Now, this is, of course, a conference about London. You may not be surprised to know that I am aware of much of what was in the Mayor’s manifesto. One of those pledges is to review the Gang Matrix system.

I am sure one of the things that Review will include is precisely how names find their way onto the Matrix and, importantly, how they find their way off it.

Sadiq will, no doubt, want to look at the oversight of the Matrix to ensure that the Met’s resources are laser-focused on policing those individuals who genuinely are involved in gang life, and pose a real threat to the safety of Londoners.

My job, meanwhile, will be to examine whether the criminal justice system uses that information judiciously at all times.

I want to be clear that information like this is tested and questioned appropriately by the Crown Prosecution Service, in the courts, by prisons and in probation services.

Part of that will be ensuring that, at the very least, each part of the system has a common understanding of what the term ‘gang’ indicates.

Part of it will be establishing what thresholds of evidence are used to decide whether individuals are, indeed, gang members.

And part of it will be clarifying what opportunities there are for individuals to challenge the validity of information that is held about them on this subject.

This is, of course, not the only issue concerning inequality between ethnic groups in the youth justice system.

Nor is it the only subject I am looking at – in what is a wide ranging review of the criminal justice system.

But when four in five people on the Gangs Matrix are black – and that database currently informs decisions throughout the criminal justice system – it is something that someone in my position has a duty to scrutinise closely.

In the coming months I intend to do just that.