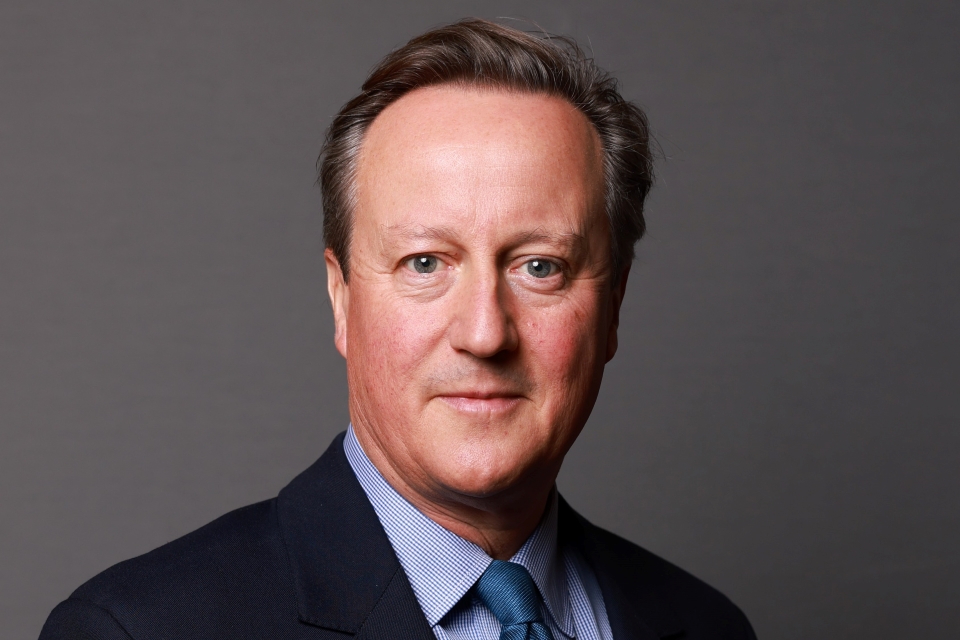

Speech to Lord Mayor's Banquet

A transcript of Prime Minister David Cameron's foreign policy speech to the Lord Mayor's Banquet in London on 15 November 2010.

My Lord Mayor, my late Lord Mayor, your Grace, my Lord Chancellor, Mr Speaker, your Excellencies, my Lords, Aldermen, Sheriffs, Chief Commissioner, ladies and gentlemen. Can I first of all thank you, Lord Mayor, for the warmth of that welcome.

I have just come back from visiting two of the fastest-growing economies in the world: China, with average growth of nearly 10% a year for the last three decades, and Korea, which in 1960 had a GDP only twice that of Zambia, but which today has a GDP forty times higher. In Seoul, I was at the G20, bringing together not only the United States and China, but also Brazil, South Africa, India, and Russia. Beijing and Seoul provide good vantage points to reflect on the huge changes sweeping our world: the rise of new great powers, the shifting balance of economic power and the tensions of globalisation. This interconnected world, the world of restless markets, so well represented here in this room tonight, is creating huge new opportunities for the countries that are able to seize them.

But this very same interconnectedness is creating new and more diverse threats to our security. The device that was found on a plane at the East Midlands Airport, which we now know was a viable and dangerous bomb, originated in the Yemen, and was carried to the UAE, to Germany, onto Britain, en route to America. Today, threats originating in one part of the world become threats in all parts of the world. As you are only too aware in the City, the threat from cyber attacks has increased exponentially over the last decade, with the last year alone accounting for more than half of all malicious software threats that have ever been identified. All of this shows how fast our world is changing, how much Britain’s interests depend on the interests of others, and why we need to maintain a global foreign policy, because our national interests are affected more than ever by events well beyond our own shores. Now, our national interest is easily defined. It is to ensure our future prosperity and to keep our country safe in the years ahead. The key question is: how do we best advance this national interest, when the threats and the opportunities are evolving so fast before our eyes?

Now, there are some who say that Britain is embarked on an inevitable path of decline, that the rise of new economic powers is the end of Britain’s influence in the world, that we are in some vast zero-sum game, in which we are bound to lose out. I want to take that argument head on. Britain remains a great economic power. Show me a city in the world with stronger credentials than the City of London. Show me another gathering with the same line-up of financial, legal, accounting, communications and other professional expertise. You know even better than me that Britain is a great trading force in the world. Whenever I meet foreign leaders, they do not see a Britain shuffling apologetically off the world stage. On the contrary, they respect our determination to get our economic house in order so that we can remain masters of our nation’s destiny. They can see the immense advantages of doing business with Britain. We are already ranked first in Europe for the ease of doing business, and we intend to become the first in the world. We are cutting our corporation tax to 24%, the lowest in the G7. We are creating one of the most competitive corporate tax regimes in the G20, cutting the time it takes to set up a new business, and scrapping the needless red tape and excessive regulation that has held us back for too long.

There is no reason why the rise of new economic powers should lead to a loss of British influence in the world, and neither is there any reason why our military power should be diminished. We have the fourth largest defence budget in the world, and remain one of only a handful of countries with the military, technological and logistical means to deploy serious military force around the world. On the day after Remembrance Sunday, I know everyone in this room will want to pay tribute to all those who have served and continue to serve our country. In terms of our role in the world, the truth is that many other countries would envy the cards that we hold: not only the hard power of our military, but our unique inventory of other assets, all of which contribute to our political weight in the world: our global language; the intercontinental reach of our time zone; our world-class universities; the cultural impact around the world of the BBC, the British Council, and our great museums; a civil service and a diplomatic service which are admired the world over for their professionalism and their impartiality. One in ten of our citizens live permanently overseas, reflecting our long tradition as an outward-facing nation, with a history of deep engagement around the world, whose instinct to be self-confident and active well beyond our shores is in our DNA.

We sit at the heart of the world’s most powerful institutions, from the G8 and the G20, to NATO, the Commonwealth, and the UN Security Council. We have a deep and close relationship with America. We are strong and active members of the European Union, the gateway to the world’s largest single market. Few countries on earth have this powerful combination of assets, and even fewer have the ability to make the best use of them. What I have seen in my first six months as Prime Minister is a Britain at the centre of all the big discussions. So, I reject this thesis of decline. I firmly believe that this open, networked world plays to Britain’s strengths, but these vast changes in the world do mean that we do constantly have to adapt. Let me turn to how.

We need to sort out the economy if we are to carry weight in the world. Economic weakness at home translates into political weakness abroad. Economic strength will restore our respect in the world, and our national self-confidence. The faster we can get our domestic house in order, the more substantial and credible our international impact is going to be. But we also have to be strategic and hard headed about how we go about advancing our national interests. In recent years, we have made too many commitments without the resources to back them up, and we have failed to think properly across government about what we were getting ourselves into and how we would see it through to success. So, in Iraq, there was no plan for winning the peace. In Afghanistan, we failed to think through properly the implications of the decision to deploy into Helmand Province in the summer of 2006. As a new government, we should learn the lessons and make changes.

I’m not suggesting that we turn the country’s entire foreign policy on its head. As Leader of the Opposition, I always made clear to foreign leaders that there was a great deal of common ground between the policies of the government and the Opposition. We want an active foreign policy that is staunch in its support for democracy and human rights, as we have been, for example, in arguing for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi and the rights of the Burmese people. Wasn’t it a fantastic sight on our television screens over the weekend to see that wonderful woman free? We want a foreign policy that is vigorous in its efforts to address climate change, which poses such a threat to humanity and which can only be dealt with by nations coming together. We will continue to build on our special relationship with America. It is not just special; it is crucial, because it is based on solid practical foundations such as our cooperation on defence, counter-terrorism and intelligence.

But in other areas, where we believe that Britain’s interests require a change of course, we should lose no time in adjusting the national tiller accordingly. I want to highlight three areas this evening. First, we must link our economy up with the fastest-growing parts of the world, placing our commercial interests at the heart of our foreign policy. Second, we’re taking a more strategic, hard-headed approach to our national security and applying that to our mission in Afghanistan. Third, we must focus more of our aid budget on building security and preventing conflict.

Let me take these in turn. First, a more commercial foreign policy. This is not just about making Britain an attractive place to invest; it’s about selling Britain to the world too. Some people think it is somehow grubby to mix money and diplomacy. I say, when it is harder than ever for this country to earn a living, we need to mobilise all the resources we can. Today we trade more with the Netherlands than with Brazil, Russia, India, China and Turkey combined. We are not making nearly enough of the opportunities out there. That’s why one of the first visits I made as Prime Minister was to India. It’s the second fastest-growing major economy in the world. I have also been to Turkey, which is growing at 11% this year, and just last week I took one of the biggest and most high-powered delegations in our country’s history to China. Next year I plan to visit Brazil and Russia. We are also rebuilding our relationships with the countries in the Gulf. They feel strong links with Britain, but have felt sidelined in recent years. I’m delighted that Her Majesty the Queen will visit the UAE and Oman next week, and I will be making my own visit early next year.

But this isn’t just about what the monarch, ministers or I do. It’s about what our ambassadors, diplomats, our hardworking staff at UKTI, it’s what all of them do day in and day out in every country of the world. I have told them every time anyone representing Britain meets a foreign counterpart for however short a time, I want them walking into that room armed with a list of things they are there to deliver for our country. Others do this; we should too.

When it comes to the European Union, we’ve shown in recent months how we are constructive and firm partners, using our membership of the EU to defend and advance UK interests. I can promise you this: we will stand up, at each and every turn, for our financial services industry and the City of London. London is Europe’s pre-eminent financial centre. With this government, I am determined it will remain so.

Next, bringing a more strategic approach to defending our national security. We set up for the first time a National Security Council which met on the first day of the government, and has weekly ever since. Foreign policy, defence policy, domestic policy, development policy - all the decision-makers not off pursuing disparate missions in different departments, but sitting round a table together asking what is best for Britain and working out how we can gear up the government machine to deliver it for our national security.

Our first priority was to set a clear direction for our military and civilian mission in Afghanistan. The fact remains that we are still the second largest contributor to the NATO-led force, with 10,000 troops there, most of them in the most difficult part of the country. We are not there to build a perfect democracy, still less a model society. We are there to help Afghans take control of their security and ensure that Al Qaeda can never again post a threat to us from Afghan soil. A hard-headed, time-limited approach based squarely on the national interest. In August, we transferred British forces out of Sangin to enable them to concentrate in greater numbers in central Helmand where the bulk of the population lives and to share the burden more sensibly with US forces across the province as a whole. I have said that our combat forces will be out of Afghanistan by 2015.

We’ve also concluded a truly strategic review of all aspects of security and defence. This was long overdue; it has been 12 years and four wars since the last defence review. We started with a detailed audit of our national security. We took a clear view of the risks we faced and set priorities including a new focus on meeting unconventional threats from terrorism and cyber attack. We then took a detailed look at the capabilities we will need to deal with tomorrow’s threats.

Yes, we made some tough choices. [Political reference] But we have ensured that our magnificent armed forces will always have the kit they need for the threats they face, whether today in Afghanistan or in the world of 2020. We will be one of the few countries able to deploy a fully-equipped brigade-sized force anywhere in the world. With the Joint Strike Fighter and Typhoon, the Royal Air Force will have the most capable combat aircraft money can buy, backed by a new fleet of tankers and transport aircraft. The Royal Navy will have a new operational aircraft carrier, new Type 45 destroyers and seven new nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarines, the most advanced in the world. And we will renew Trident, our ultimate insurance policy in an age of uncertainty.

My determination is that Britain will have some of the most modern and flexible armed forces in the world. But our security does not depend on our military forces alone. That’s why we have also given priority to investment in our counter-terrorism capacity and new programmes to improve our resilience against cyber attack, and ensuring that our world-leading intelligence agencies are able to maintain their brilliant work in disrupting threats and keeping our country safe.

There’s one more area where, despite the economic pressures we face, this new government has been determined to hold firm: our commitment to spend 0.7% of our GDP on aid by 2013. We will meet that target and we will do so for good reasons. Our aid programme, like the activities of the myriad of charitable aid organisations, literally saves lives. It helps prevent conflict, which is why we have doubled the amount of our aid budget that is spent on security programmes in countries like Pakistan and Somalia. And for millions of people our aid programme is the most visible example of Britain’s global reach. It is a powerful instrument of our foreign policy and profoundly in our national interest.

That theme - pursuit of our national interest - has been at the heart of everything I have said this evening. Our foreign policy is one of hard-headed internationalism. More commercial in enabling Britain to earn its way in the world, more strategic in its focus on meeting the new and emerging threats to our national security, and firmly committed to upholding our values and defending Britain’s moral authority even in the most difficult of circumstances. Above all, our foreign policy is more hard-headed in this respect. It will focus like a laser on defending and advancing Britain’s national interest.

That concept of national interest is of course as old as our nation itself and I am conscious of the many Prime Ministers who have stood here before me and set out Britain’s national interest as they saw it. Many of them have confronted circumstances more perilous than those which face Britain today. But few perhaps will have dealt with a world that is changing so fast. From Beijing to Seoul, from Washington to San Paolo, leaders must work out what it all means for their countries and where their national interests lie. When some people look at the world today, they are quick to prophesy dark times ahead, difficulties for Britain. Our foreign policy runs counter to that pessimism.

We have the resources - commercial, military and cultural - to remain a major player in the world. We have the relationships, with the most established powers and the fastest-growing nations, that can benefit our economy. And we have the values - national values that swept slavery from the seas, that stood up to both fascism and communism and that helped to spread democracy and human rights around the planet - that will drive us to do good around the world.

With these strengths in our armoury we can drive our prosperity, we can increase our security, we can maintain our integrity. We are choosing ambition. Far from shrinking back, Britain is reaching out. And far from looking back starry-eyed on a glorious past, this country can look forward clear-eyed to a great future. Thank you.