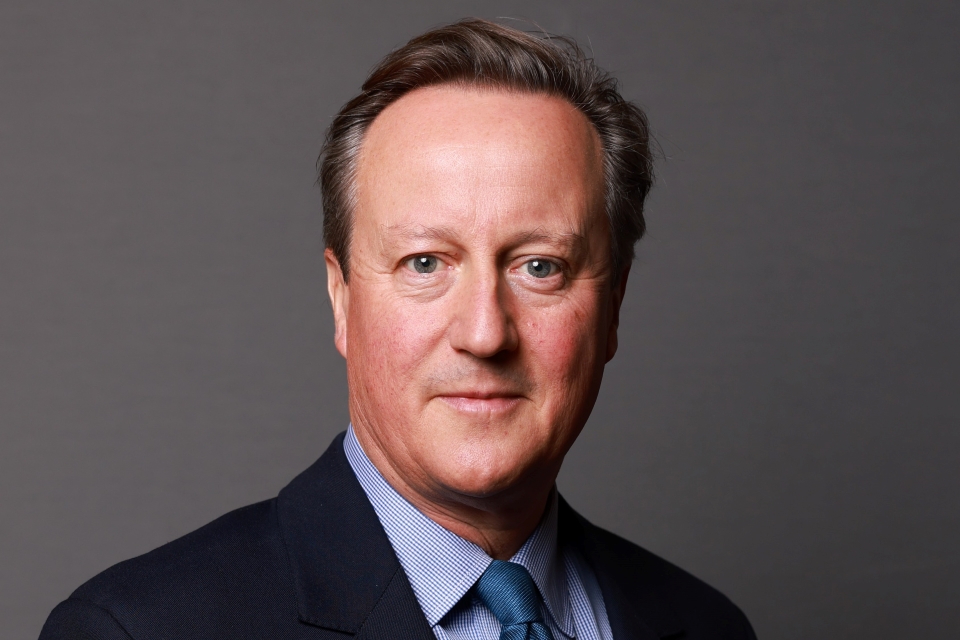

Transcript of David Cameron Q&A at New York University

Prime Minister David Cameron answers students' and professors' questions at New York University.

Watch an archived version of the live webcast (Skip to 16:00 to watch the start of the event)

Watch live streaming video from nyutv at livestream.com

Prime Minister

Well, thank you very much for that warm welcome. But above all thank you for being here because I’ve just realised that this is spring break. So, you must be the most devoted students and you are not the ones who are taking the break in Florida or elsewhere. So, thank you for coming and also thank you for being patient and waiting for me.

This session is about your questions and my answers, not long speeches. I just wanted to say one thing about the visit I’m making to the United States over the last couple of days.

It’s been in many ways a celebration of, an acclamation of this special, this essential relationship between our two countries. And obviously there have been some great ceremonial occasions and sights and things that I won’t forget. It was incredible to be able to make a speech outside the White House, particularly as we tried to burn it down 200 years ago. I’m a passionate fan of our shared history. And I enjoy very much reading into that history and all the things that our countries have done together.

But the reason that I’m passionate about the special relationship is as much about the future as the past. I think if you look at the big challenges that we face in our world, whether it’s the challenge of economic performance and making sure our people get decent jobs, or whether it’s the challenge of security and fighting terrorism, those are two thoroughly modern reasons for believing in the special relationship today. Because when it comes to fighting terrorism, we’re never going to solve it just by military might and the might of the US in particular on its own. We need to combat terrorism with all the resources we’ve got, with the smart power, with the aid budget, with the diplomacy, with political moves, with bringing together and forming great networks and alliances. And Britain has a lot to offer on that front.

And when it comes to building prosperity I greatly admire what’s happening in the US economy and the growth and jobs that are beginning to come through. But in an interconnected world, and a world in which China may not grow as fast as people previously expected, actually the fact that half of the world’s trade crosses the Atlantic says to me that we should do even more to try and trade more with our traditional partners as well as trading out into the South-Eastern parts of our world. Often in business, you find that you get the best by going after your oldest customer and trying to sell more. And I think Britain and America, and America and the EU, should be trying to deregulate and trade far more with each other as one of the ways of getting prosperity in our world. So, two reasons why the special relationship is just as important today as it has been in the past when we’ve stood shoulder to shoulder fighting conflicts, whether in Europe, the Korean peninsula or elsewhere.

That was all I wanted to say by word of introduction. It’s an honour to be here at NYU and to be with you. Let’s try to get through as many questions as we can in 45 minutes; who wants to go first?

Question

I know that you and President Obama have talked a lot about the different approaches to combating the recession and in some ways I think that you two have tried to gloss over the differences and in many ways it undermines the distinct approaches that Britain and the United States have taken. Is Keynesianism in your view dead? Should the United States not have pursued the stimulus that it did? You noted in your comments yesterday that the United States was taking more of an approach - the British austerity approach. How do you react to that and also, to what extent do you think that Keynesianism will not be an approach in future for the United Kingdom?

Prime Minister

Okay, I don’t think there’s a huge difference between our approaches. We both want to encourage growth, we both want to deal with our deficits, we both realise that we’re borrowing too much money, that we’ve built up too much debt and we have to deal with that. The differences are really between the natures of our economy. The US can afford to take longer over this issue because it’s a reserve currency.

And also there’s another difference between Britain and America which sometimes gets overlooked. We have a large welfare state. We have very big automatic stabilisers as it were, so when we get hit by recession, spending goes up automatically. I think that sometimes people look at the US stimulus and forget that of course, with much smaller welfare state you don’t get that sort of deficit spending that we get automatically. So, I think the differences are overdone.

As for Keynes, my view is quite simple. Of course government can stimulate economic activity by cutting taxes or increasing spending - that can work. But I think you do have to recognise that when you have a situation where you’re borrowing around 10% of your GDP as we were in 2010, when your debt-GDP ratio is growing, when the markets are beginning to question ‘Are you going to deal with your deficit?’, ‘Are you going to be able to pay your debts?’, then the idea that a fiscal stimulus would actually really boost your economy, when actually you would get punished by the markets and your interest rates would go up, I think is very questionable.

So, I think you have to be practical about these issues. And the truth is, for Britain right now, if we were to say, ‘Okay, let’s just loosen the purse strings, let’s spend a bit more money’ or ‘let’s cut those taxes’ without saying where the money’s coming from; ‘let’s do that and stimulate the economy’ - you might put in £3, £4, £5 billion into your economy, but if your interest rates went up - and ours are at a 100 year low - that would take money out of the economy and would you be left with any net stimulus? I think the opinion of most economists that I respect is that you wouldn’t really get any stimulus.

In fact, you might get a negative stimulus because your interest rates would shoot up and you’d suffer in that way. And we don’t necessarily have to imagine it in Britain because we can look across Europe and see other countries with deficits smaller than ours, whose interest rates are much higher than ours. They stand as a warning as what happens if you lose the confidence of international investors. Right now, people look at Britain and say, ‘Yes, you’ve got a big debt, you’ve got a big deficit, you’ve had a difficult recession, you’re beginning to grow out of it. But I know you’ve got a plan to deal with your debts and deficit and because you’ve got a plan, we’re prepared to trust that plan and keep your interest rates low.’ And that I think is really important.

Question

Mr Prime Minister, I’m an international student from Scotland. You were there last month and you described yourself as a patriot of the whole United Kingdom and indeed came out to say you’re against an independent Scotland. My question was, in the 2010 election your party won more than half the seats in England but it won just one of the 59 in Scotland. And I was wondering, do you not feel that the political DNA of the country is just different and it’s actually possibly becoming anti-democratic in the sense that one in 59 seats elected, yet you’re the Prime Minister of Scotland also?

Prime Minister

We introduced devolution into the United Kingdom to deal with exactly the question that you say. So, Scotland has its own parliament, has its First Minister, and has the ability to set its own policies on everything from education and health and housing. So, we’ve devolved power. So I think that is the first point.

The second point is yes, my party might only have got one of the seats, but if you actually count up who voted in the general election for parties who believe in the United Kingdom, you have to add up Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat and we considerably outpolled the Scottish National Party which is the party of independence and separatism.

When it came to the elections in Scotland for the Scottish Parliament, people were being asked a slightly different question, which is, ‘Who do you want to be the First Minister in Scotland?’ and they decided to vote SNP rather than voting Labour. So, I don’t feel any lack of legitimacy. I’ve always said we need to govern the United Kingdom with respect and so, as a Conservative Prime Minister in a coalition government, I’ve always dealt with the First Minister with respect. But when you have a situation where a part of your country is asking if it can have a referendum on breaking away, you have to grant that referendum. And that’s exactly what we’re trying to do.

But I’ll say very clearly to people in Scotland and indeed, to people in England and the rest of the United Kingdom, ‘Please don’t go. I want you to stay. I want to keep the United Kingdom together; I think it would be a tragedy for this incredibly successful partnership to split up. But it will be for the Scottish people to decide. But my job, I think, is to say to them, ‘We want you to stay’, and also to say to the English people that we benefit in England from this great partnership with Scotland, and don’t let’s give any impression that we would like Scotland to depart - we wouldn’t.

Question

It’s an honour, Prime Minister. I’m an MBA student at Stern. The Guardian’s Martin Kettle stated in an article yesterday that your visit to the US symbolised an official end to the neoconservative era that began post-9/11 and the start of an era of disengagement. Would you agree with that, and if so, what would the US and UK future responses look like to the Syrian conflict if it progresses, and a potential Iranian/Israeli conflict?

Prime Minister

I wouldn’t agree with the premise. I’d agree with part of the premise. Let me explain. I don’t think that in any way President Obama or I could be accused of being unengaged in the world. In the case of Libya, where there was a dictator who was murdering his own people, we acted very decisively. We assembled an international coalition with the backing of the United Nations, with the backing of the Arab League and we took decisive military action which helped the Libyan people to free themselves from this tyranny and to get rid of one of the most brutal dictators there’s been, who’d run that country for 42 years. So, I don’t accept we are somehow withdrawing from the world. We held a conference on Somalia during the last month, bringing together countries from all over the world to try and help mend that deeply broken country. And that’s going to take a combination of approaches - yes, there’ll be military aspects to it, but there are also aid, diplomacy and many others too.

What I think has changed is this recognition that in order to make our world safer, to defeat terrorism, to drain the swamp on which terrorism depends; we need to be smart as well as strong. We need to recognise that military power is important, but it’s never going to be enough. If you take the example of Somalia, of course you’ve got to defeat Al Shabaab, you’ve got to defeat the terrorist organisation. But in Somalia, you’ve got a country where young people have no prospects, no hope; where people are better off becoming pirates than trying to work in the proper economy. You’ve got famine in the Horn of Africa. You’ve got deep division throughout the country. You’ve got to try and solve those using aid, diplomacy, all the other tools in the toolkit rather than just military action.

So, I describe myself – which for an American audience, I know, is very tough – as a liberal Conservative. What that means in British terms is a ‘liberal’ foreign policy because I think we should be actively engaged in the world; we should be trying to spread human rights and democracy; we should be working with those that want to achieve those goals. But the Conservative bit of me is that we should be sceptical, we should be careful, we should be cautious; we should be asking questions about the grand plans and schemes to remake the world, because it’s no good in international affairs to do something, or to start to do something, unless you know how you’re going to finish it.

I described it the intervention in Libya as ‘necessary, legal and right’, but maybe I should’ve added a fourth word, which was, ‘achievable’. We knew that actually we had the military power to achieve what was necessary to allow the Libyans to try and take control of their own country. And I think when you look around the world at different challenges, I think it’s all very well to say, ‘There’s a moral force to act here’. As well as the moral force, you need to be able to be clear that you can achieve what you’re setting out to do.

Question

Good afternoon, Prime Minister. My name is Hill Krishnan. I teach International Relations in the Global Affairs department at New York University. And I’m a proud American and I’ve been trained by the US Department of Energy, Nuclear Non-Proliferation Safeguard and Security. Now, you can know where the question is going. It’s a two-part question. While we do the important job of urging Iran to not achieve nuclear weapons, what is UK doing to reduce its stockpile or eliminate its nuclear weapons? That’s my first point.

Second is that I’m running for City Council for New York City; and as a beginning politician, what would you recommend for me? What advice would you give me?

Prime Minister

On the first question, Britain has got a pretty good record of reducing the size and the scale of our nuclear deterrent. We have reduced the number of our warheads considerably over recent years. We’re one of the original nuclear powers. We’re not going to dis-invent nuclear weapons in our world and so I believe the British position, that we will maintain that nuclear deterrent, renew that nuclear deterrent so that it is fit for purpose, is the right thing to do. It is, for a country like mine, just as it is for a country like yours, the ultimate insurance policy in an unsafe and dangerous world. So, yes, it’s expensive to have submarines that can be continuously at sea, as your Ohio class and our submarines are able to do, but I think it’s right for our countries.

The question with Iran is that it would be dangerous for the whole world, it would be dangerous for the region, for Iran to have a nuclear weapon. But also, you’re dealing with a country that has expressly said it wants to wipe Israel off the map. And so, I think it is a clear danger to the world, Iran having a nuclear weapon. And that is why I think Britain and America and other countries are taking every action we can to pile the pressure on Iran to take a different path. To say to the Iranians, ‘If you want civil nuclear power, you can have civil nuclear power and we’ll even help you to make sure you achieve that in a safe way. But you should not be heading towards a nuclear weapon’.

As for the advice on the politics, I think you’re making a good start. ‘All politics is local’, they say, so you’re starting at the right level. I think the most important thing in politics is to say what you think; to do what you say; to be clear and frank about where you stand. The thing I always find about politics is that even if people aren’t that interested in politics and policy and what you’re saying, they have a brilliant way of determining whether you mean what you say. And they see through people who take a position that they don’t believe in. And your authentic sense of who you are and what you want to achieve, if you communicate that, you’ll be just fine.

Question

You are generally critical of the human rights framework in the United Kingdom and the Human Rights Act in general and obviously the recent decisions of the ECHR don’t help people advocating the Human Rights Act. And you’re more in favour of a Bill of Rights for the UK. How, or what, is your plan on trying to achieve this and how can you do this with a coalition with the Lib Dems?

Prime Minister

I am a strong believer in human rights. Britain has an excellent record on human rights and we’ve had rights for our citizens through our Parliament for centuries. We have a problem right now - the European Court of Human Rights in some instances has made judgements that make the act of government and keeping your people safe very, very difficult.

We have a particular situation with people who have no right to be in the United Kingdom – they’re foreign nationals – people who we are absolutely clear are a security threat to our country but who we are completely unable to deal with. We cannot prosecute them because we don’t have enough evidence to put in front of a court, not least because we don’t use intercept evidence in courts. We cannot detain them, because it’s a right not to be detained without trial. And yet crucially, we cannot deport them, because the European Court of Human Rights has basically passed a series of judgements saying that if there is any risk whatsoever to this person following their deportation, then you absolutely cannot deport them.

So, there’s a lack of balance, in my view. You ought to be able, as a country – that believes in freedom and human rights and democracy and all the rest of it – you ought to be able to make a balanced judgement about what is the danger to Britain if this person stays in our country; and what are the risks to them if they are deported.

And in the particular case of Abu Qatada, whose also wanted here in the US, it has been extremely frustrating, because the Court said, ‘You can’t deport this man to Jordan because there’s a danger, if he goes to Jordan, he’ll be tortured’. So we thought, ‘Right, okay, fair point’. We went off to Jordan and we did a deal with Jordan; signed a deportation-with-assurances agreement that there was no way he would be tortured if he was sent to Jordan. Went back to the Court and the Court said, ‘No, sorry, he can’t go to Jordan because he can’t be tried in Jordan because some of the evidence used might be the product of torture’. So, again, we’ve gone back to Jordan to try and sort that issue out, and it is immensely frustrating because this person has absolutely no right to be in the United Kingdom, he has no family ties to the United Kingdom, and yet we have no ability to deport them. And so I feel there’s a lack of balance in the situation.

I hope that a British Bill of Rights would restore some of that balance because it would be a Bill of Rights written in Britain and then dealt with in British courts and that’s why I’m pursuing it. Obviously I’m in a coalition government between Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, so there are some disagreements over this area, but we’re trying to work through them. It’s an area if I was in government alone I’d be able to go a bit further and faster, because I do think that the first duty of a government is to protect the security of its citizens, and while I believe profoundly in the rights that we all have to fair trial and freedom of speech and everything else, at heart I believe that if you’re a country and if someone comes to your country and has no right to live in your country and they threaten your country, you ought to be able to say, ‘I’m sorry, you can’t come in’ or ‘you can’t stay’. I think that is quite a fundamental right and one that isn’t properly being recognised.

Question

Prime Minister, my question is about the UK’s National Health Service. You’re planning on giving more control of the National Health Service budget to local doctors, general practitioners to increase competition. Your critics claim that you’re planning on privatising the National Health Service and going too far, but you deny this. My question is, why are you not doing more to privatise the National Health Service? Is it just because you’re making concessions for your coalition partners?

Prime Minister

No, I’m not going further to privatise the National Health Service because I don’t want to privatise the National Health Service. I think we have an excellent healthcare system in the United Kingdom. We have a very simple founding principle for the NHS, which is that it is free at the point of use, it is available to all and it’s available based on your need rather than your ability to pay.

It’s a brilliant and clear system. In Britain, if you fall ill or if your child is ill, you turn up at hospital, you turn up with your GP, and you get first class treatment. They never ask you for your credit card or how much you earn or whether you’ve got insurance, and it’s an enormous expression of our solidarity for each other in the United Kingdom. And I’ve seen from my own perspective just how powerful that is and what it means as a father of a very ill child.

I don’t want to change that principle at all, but I think we can, in Britain, make our health service a bit more flexible, and the point of our reforms is to put the power in the hands of the family doctor and the budget in the hands of the family doctor, so when you go to the doctor you have a choice. You can choose which hospital to go to, you can choose whether your services are going to be provided by some brilliant voluntary organisation like Marie Curie Cancer Care or Macmillan Cancer Support, or whether you’re going to go through other parts of the health service. A more choice-driven system, a system that has more competition within it, that welcomes the independent, voluntary and private sectors into the NHS, but on the basis that they’re not charging anyone.

So that’s the vision of what the health reforms are all about. They’ve been controversial, I think, partly because if you propose change in any public service, you always stir up opposition of those, many of whom care about it deeply, who are wary of change and also people who work in the service who are nervous of change. That doesn’t mean change is wrong. It just means that in politics you have to think carefully about what you’re going to do, prepare the ground carefully, make your arguments, try and take people with you, but on occasion you won’t take everybody with you, but you have to just go ahead and make the changes if you think they’re right.

And it’s the same challenge all over the world. I was in Newark this morning with Mayor Booker and they’re making great reforms in their education system. Part of that reform is a new deal with the teaching unions, so that there are better and more flexible ways of employing teachers, and frankly when teachers aren’t doing a good job, making sure they leave the profession. Now, that’s a tough reform. It’s going to be a difficult thing to deliver. But if we’re all going to have good public services that are good value for money that give us excellent healthcare and better education for our children, we should be pressuring our politicians to make these reforms, not saying, every time you attempt one, that you’re trying to break up a service that is much loved. These reforms are vital if we’re going to be competing and succeeding as advanced countries in the world in the years to come.

Question

I’m a business student here at NYU and also Dean at New York Medical College. Following up on National Health Service, sir, you may have heard that we have a somewhat different system here.

And I gather from recent conversations with both Democrats and Republicans that most are thinking towards making further changes in the system, whichever way we go in the coming election. What advice would you give our leaders on elements of the system in Britain that are very good and are there some sticky wickets that you might warn us about?

Prime Minister

Well, we start from such different points, and there are many similarities between our countries, but I think healthcare is one where you started from a particular position and we’ve started from a totally different position. We don’t want to adopt your system and from what I read about your politics, people in your system don’t want to adopt ours. So I think there’s only a limited amount of crossover. I think there are some things that we can learn from each other. I’d say one of the strengths of the British system is the family doctor service, the fact that everybody knows the name of their general practitioner, they’re a really good guide through the system. I think that primary care is one of our strengths. I think you’ve got some great strengths in the way that your universities collaborate in terms of medical research and I’m sure there are things we could probably learn from each other on that basis. But, as I say, very different systems.

We’re never going to move to an insurance-based system. I wouldn’t want us to, I don’t want to see charges in our health service, but I do think you can have a free system with more choice and competition and therefore more quality, rather than moving to an insurance-based system. I’d guess the one thing that we all have to do is recognise the patient is getting more and more savvy about their own healthcare, and so we should publish far more in the way of results, we should make much more information available, we should have much greater transparency. And I think we should also recognise that in the modern age people want far more of a say about how they manage their care. One of the great challenges to all our healthcare systems is the amount of people who are going to be living with lifetime conditions, whether it’s diabetes or in later life dementia. We’re going to have to tailor healthcare packages around patients far more and give individuals much more say about the healthcare they receive.

Question

I work at NYU in the research - in the equivalent of the research ethics committee, but I’m from an English background. I’m married to an Argentinean - so you know where I’m going. With all the things the President of Argentina’s is doing, do I have to worry about another split in my house like what happened 30 years ago?

Prime Minister

No, I don’t think you do. It is the 30th anniversary of British action in the Falkland Islands, and I want to be very clear on this - where Britain stood, and Britain stands, is in a very simple and straightforward place, which is two words: self-determination.

We’re not very far away from the United Nations building. Part of the United Nations Charter is self-determination, and that is that the people living somewhere should have a right to determine what country they’re part of, who governs them, and the fact is, the people in the Falkland Islands - and I know there aren’t many of them, we’re only talking a few thousand - could not be clearer that they want to continue their status as an overseas territory of the United Kingdom.

And the message I wanted to send to everybody this year, the 30th anniversary year, is as long as they want that, that is not going to change, that Britain will continue to protect and defend them. And I knew there was going to be a lot of noise and diplomatic activity from the Argentineans and all the rest of it, and I didn’t want anyone to misread the situation, because 30 years ago there was some uncertainty about Britain’s intentions, so I want to be absolutely clear: we believe in self-determination. I think most people in the United States would believe in self-determination, otherwise where would we be? Things might rather different.

Self-determination, that’s the key. There’s no reason why Britain and Argentina can’t have cordial relations, but they should be based on the fact that the people in those islands have very clearly said what country they want to be part of.

Question

Prime Minister, my name’s Amanda, I’m a policy student at the Wagner School of Public Service. So you have an Olympics coming up, which is really exciting. Do you have any worries on your radar policy-wise of planning, transportation? The Olympics are a really exciting time for a country and I remember back a few years ago when we were putting in the bids for New York and Chicago, what do you have on your radar as concerns?

Prime Minister

The Olympics start in July, here we are in March. We’ve got a glistening Olympic park; all the main venues are completed. They look immaculate. I’ve been to the aquatics centre. I’ve been to the velodrome. I’ve been to the main stadium. Not only do they look great, we’ve also secured future uses for almost all of them, so there’ll be a real legacy from these Games. So I’m very confident that 2012 is going to be a great year for Britain.

People are going to come for the Olympics from all over the world and enjoy a fantastic couple of weeks of sport. The problems are always the same, there’s always a worry over security, over terrorist threats, over making sure that people are safe and secure. We’ve done everything we possibly can to make sure that’s the case, but you know, we live in a world where you have to be permanently on the case.

Transport is obviously key - getting people into the country and getting people around the country. We’ve put in a huge amount of effort, London isn’t a small city that you can just shut down while you have an Olympics. Life is going to go on, life is going to be different for a few weeks, because there will be bigger queues and there will be some delays, but it’s going to be an amazing few weeks. So I’m confident that we can crack those problems, I’m confident it’s going to be a great Olympics.

We’re looking forward to welcoming people from all over the world. The challenge we have is obviously we did quite well in Beijing, we came fourth in the medals table, and so we’ve got our work cut out. People have always said in Britain, the sports we do best are the sports you sit down in, so cycling, riding, rowing and sailing we’ve got a lot of great hopes, but we’ve got some brilliant heptathletes, we’ve got some very good long distance runners. Lots of things. So it’s going to be a great fortnight.

Question

Mr Prime Minister, you just talked a little bit about your goals for keeping the National Health Service available. Another public service in England that has changed a lot very recently has been university education. So what are your goals for maintaining university education as something people of all classes can afford?

Prime Minister

The key with university education is that we’re living in a global world where the training and the brains that we have in our countries are going to be the key natural resource. And so I’m absolutely clear, the absolute priority with universities has got to be to maintain the quality, and that’s why we’ve taken a very difficult decision as a government and increased, quite substantially, the fees that people pay when they go to university. So it’s now, I know this doesn’t sound like a lot in American terms, up to £9,000, about $14,000 a year. It was only £3,000, so it’s a big increase.

What this means is that we’ll be able to keep the quality of our universities up and also, we’ll be able to keep the number of people going to the universities up. We’ve made it affordable to the tax-payer and for the government. I also believe we’re keeping it affordable for the individual, because the great thing about our system is that although you’re being charged up to £9,000 a year, you don’t start paying back anything until you’re earning, basically, $30,000.

So we’re making a choice, which is, you can either fund universities from tax-payers or you can fund universities from the people who benefit most which are the successful graduates. And I think our system is the right answer, we’re going for the successful graduates. Not just all graduates, because if you leave university and you never get a well-paid job, then you won’t have to pay back that money. I think that’s the right choice, and I think in Europe where a lot of university systems are still free, others will start to recognise that if we want good universities, well paid tutors, well stocked libraries, good research facilities, we’ve got to pay for them. Where’s the money coming from? Better to take it from the successful graduate. And I don’t see any evidence so far, and we’re only in year one of operation, that people from low income backgrounds are steering clear of university, because they know that they pay nothing up front, they only start paying when they’re earning around $30,000. It’s a good system.

Question

I’m an adjunct professor here, and a former member of the City Council here in New York. A lot of Americans are concerned about the price of gasoline, and with a potential event in the Middle East and Iran, potentially spiking that even further, there’s been some talk of release of the strategic petroleum reserves. I’d like to hear your thoughts on the conditions that would warrant that and the effect you’d hope that would have.

Prime Minister

President Obama and I discussed this issue yesterday. Now obviously, what we call petrol, what you call gas, prices are having a big effect on families, there’s no doubt about it.

It does have a big effect on consumer confidence, it obviously affects household budgets and we’d both like to see global oil prices at a lower level than they are today. We didn’t make any decision about the release of global oil stocks, reserve stocks, this has to be discussed more broadly. We did this last year when there were some particular supply disruptions including of course, the disruption of Libyan production.

So we’ve got to look at this issue carefully because any move on this front ought to recognise the supply disruptions and therefore, to try and smooth out the price. But I think it is something worth looking at, because it’s having an effect on all our economies, on all our families, on our budgets, but I think there’s a wider lesson that we’ve got to learn. Which is we’ve got to become less reliant on hydrocarbons, on petrol, diesel and everything else. We’ve got to wean our economies off this addiction and I think that means in energy production looking at renewable energy and nuclear power as well as fossil fuels. I think in terms of the automotive industry, we’ve got to try and speed up the move towards electric cars and hybrid vehicles. And that’s taking place quite rapidly in our country. And I think it also means a more decentralised energy system where you have an ability to generate power and sell surpluses back to the electricity grids, which we’re making some progress with in the UK. But short term, should we look at reserves? Yes we should.

Question

Mr Prime Minister, I’d like to speak with you about two events that happened last year. Last summer, we obviously had the riots in London, with largely youth-based, largely low-income riots. At the same time there was a flat sold in Knightsbridge, designed by Mr Rogers, for I believe £100 million. My question is for you is, in an age where cities are now lived in by over 50 per cent of the world, what is the vision and plan to make cities in the UK more accessible for people, not just profits or the wealthy. I know His Royal Highness has spoken heavily about this - Prince Charles often comes out speaking about cities. What is your position and vision for cities across the UK?

Prime Minister

Well that was actually one of the reasons why I was in Newark this morning, because I think in the US you have cities with some huge challenges. But I think you’ve got this tradition of civic leadership where people who’ve got a lot to offer can come forward and stand as mayor. You’ve got some not so good mayors, but you’ve got some great mayors who’ve been enormous catalysts for change in their cities.

London has a city mayor in Boris Johnson, but the other great cities of the United Kingdom - Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds - don’t have mayors. I think that part of the answer is great civic leadership, and that’s why we’re having referenda across these cities in May to see if people want to vote for having a mayor. And I very much hope that they will.

On the riots, I think what was very clear about it, just at the time and afterwards, that these were not riots based on social pressures or racial pressures. It actually was a mass outbreak of lawlessness, where the police briefly lost control of the situation and it was really just a lot of people stealing property from shops and looting rather than there being any profound racial or social unrest causes. And I think that is why it broke out very suddenly, it was got under control relatively quickly, and there hasn’t been much of an after effect.

Of course we have huge challenges in our cities of making sure we have more good schools so you give young people a greater accelerator in life. Of course we need to make sure we have better policing, better housing, all sorts of social issues we need to address, but I don’t think those riots were similar to the ones we saw in previous decades. But as for cities, I say greater civil leadership is one of the ways to galvanise action. In Newark, I was impressed by all the things Mayor Booker showed me, I think it is a good example of how you can turn around a tough economic and social situation and actually restore some hope to a community.

Question

On the subject of race, since the UK went before the UN committee on racial discrimination last year, I was wondering what additional measures the government has introduced in order to prevent racial- and caste-based discrimination? I’m aware of the social mobility strategy, could you speak to that?

Prime Minister

Yes. I would say, Britain is a fair country, a country where of course we have our share of challenges about racial inequality and social inequality and poverty, but I think we do have a very good set of laws to enforce that equality and a good set of practices to make sure that happens. We’ve come a long way, just as America has. We’ve come a long way from the days when there was overt and open racial discrimination in our country. We’ve got more to do, but I think that we have a legal framework in place that we can be very proud of.

I think the challenge is what you mentioned, which is okay if you’ve got the legal framework, but what more can you do to make sure that people from poor backgrounds and often immigrant backgrounds and different racial groups, what more can you do to make sure that the doors of opportunity are as widely open to them as others?

I would say the big change this government is making is in terms of looking at inequality. Instead of just asking the questions; ‘How much money has everybody got?’, ‘How close are you to the poverty line?’, ‘Can we give you a bit more money to push you over a particular poverty line and make the figures look better? Instead of just looking at the monetary aspects of poverty, this government is really asking ‘What are the things that could propel you up the ladder in life?’ Let’s put more into early-years childcare so that mums can go out to work and make a better future for themselves and their families. Let’s make sure we have more independent schools within the state sector, your charter schools, our free schools or academies, so you have really great educational opportunities for children from deprived backgrounds.

We’ve actually introduced this thing called a ‘pupil premium’, which means that if you are a child who is entitled to free school meals, when you walk into that school you carry more money on your head. So the schools with the poorer pupils get more money than other schools. In some ways that is the opposite of what has happened sometimes in America, sometimes you’ve had a situation where because of property prices feeding educational budgets you’ve actually had wealthier kids in wealthier areas getting better funded than poorer kids in poor areas. We are absolutely saying the poorer kids get more money going to their schools.

I think that could be a real driver for better social mobility, which is the true modern answer to dealing with inequality once you have the legal framework in place.

Question

I’m a villager, one of the big problems in the United States has been for the past few years employment. I’d like to know what is the level of unemployment in Great Britain, and what your administration has been doing in order to stimulate jobs?

Prime Minister

Your level of unemployment in the US and our level are not far away from each other. We’re both somewhere around the 8.5 per cent mark, which is far too high. When it comes to youth unemployment, again, our figure, over 20 per cent, is far too high. We’ve both suffered from recessions, this great boom and bust that took place that meant a lot of people lost their jobs. And the challenge for both our governments and both our countries is how you help people back into employment.

What we’re focusing on is something called the ‘work programme’, where we’re asking the private sector and independent sector to come forward and be paid by results. So we’re saying to these organisations, for every person you can get back into work, because you’ve trained them, helped them and got them a job, we’ll pay you.

The thing we’re doing which is really innovative is we’re saying, for those people who have been out of work for a long time, who maybe have been on sickness or other benefits, we will pay you more money for tackling the hardest cases. We’re doing something very innovative, which is in order to pay for this we’re using the future welfare saving. Of course if someone sits on unemployment benefit or welfare year after year, it’s costing the taxpayer a fortune. It has often been argued, why not use some of that money to train them now to get them a job? So in some cases we’ll be paying these organisations up to $20,000 to place one person, who has been on sickness benefits for many years, into a job, as long as they keep that job for a certain period of time.

So we’re using a very modern mechanism to help train and get people back into work. It’s going to be hugely challenging, unemployment is too high, we need to get growth in our economy growing faster. We also have this challenge which is we’ve all got these big deficits, we’ve all got this big debt, so we’re having to make cuts in the public sector at the same time as growing the private sector.

What our recent unemployment figures showed is while we are actually losing some jobs in the public sector because of the cuts, we’re generating more jobs in the private sector than are being lost, but we need to generate even more in order to eat into the unemployment rate, because the workforce is growing and more people want to work.

So there are massive challenges. It is the biggest challenge that we have right now in the UK. I think we’ve got the right tools and methods to do it. Long-term the answer for all of us, I think, is going to be to rebalance our economies, to make sure we start making things again, to spread wealth across our countries, to make sure it’s not just focused in the City of London or the city of New York, but to try and expand the breadth of our economies, which is a bigger, fundamental thing we need to do.

Question

I’m an international student at NYU Wagner School of Public Service. Just two quick questions, one is looking at land grabs in Africa, what is your government doing to curtail the activities of land grabbers, particularly that do not translate to improvement in the living standard of local people?

Second question, recently a Briton was murdered in Nigeria. A few days ago, just about five days ago, about 100 Nigerians were deported to Nigeria from Great Britain. I just want to find out: is there a correlation between that?

Prime Minister

Taking your second question first, there was absolutely no connection between those things. Very tragically a British man was kidnapped in Nigeria by Boko Haram, which is an offshoot of Al-Qaeda. And in the attempt to rescue him, which I authorised, very sadly he was killed by the people who had taken him hostage. These are very, very difficult issues to deal with, very difficult things to have to do, and I feel desperately sorry for his family and for all his friends to have lost him in this way. But that was done working with the Nigerian government, in the full and proper way.

Of course we have a lot of Nigerians in Britain, many of whom are absolutely right to be there and fully legal. But we also have quite a lot of people in Britain who don’t have the right to be there, and we’ve also had a particular issue with quite a lot of Nigerians who have been in British prisons who we want to go and serve their sentences back in Nigerian prisons. So there are moves, over time, to deport people from Britain back to Nigeria, but there would be no connection between those two things. I think relations between the British government and the Nigerian government - President Goodluck Jonathan is someone I talk with regularly - are extremely good.

On your other point about land grabs in Africa, I would make this point. Britain has an absolutely excellent record in providing overseas aid. We are one of the few countries that have met the promise that all these world leaders made at Gleneagles, 0.7 per cent of GDP. We will make sure that we help African countries that have real problems with poverty, real problems with avoidable deaths from lack of immunisation, malaria and all the rest of it, we will help.

I think when it comes to the way that businesses can behave and the way that African governments need to respond, then there is only a certain amount that we can do from the West. What we desperately need to happen is to have governments in Africa that are prepared to deal properly, transparently and sometimes, toughly with companies that invest. Yes, there are things we can do by making sure that our companies sign up to these transparency initiatives, and Britain often leads the way on those things, but at the end of the day you are also going to need African governments that are very transparent and tough in the way that they deal with incoming investors. That has not always happened in the past. I think there is a huge agenda here where we stop speaking simply about the quantity of aid, important as it is, and start talking about what I call the ‘golden thread’, which is you only get real long-term development through aid if there is also a golden thread of stable government, lack of corruption, human rights, the rule of law, transparent information. All of those things are absolutely vital to make sure our aid effort is translated into real growth in living standards on the ground throughout particularly sub-Saharan Africa.