Crimes against businesses findings 2014

Published 23 April 2015

Applies to England and Wales

Executive Summary

-

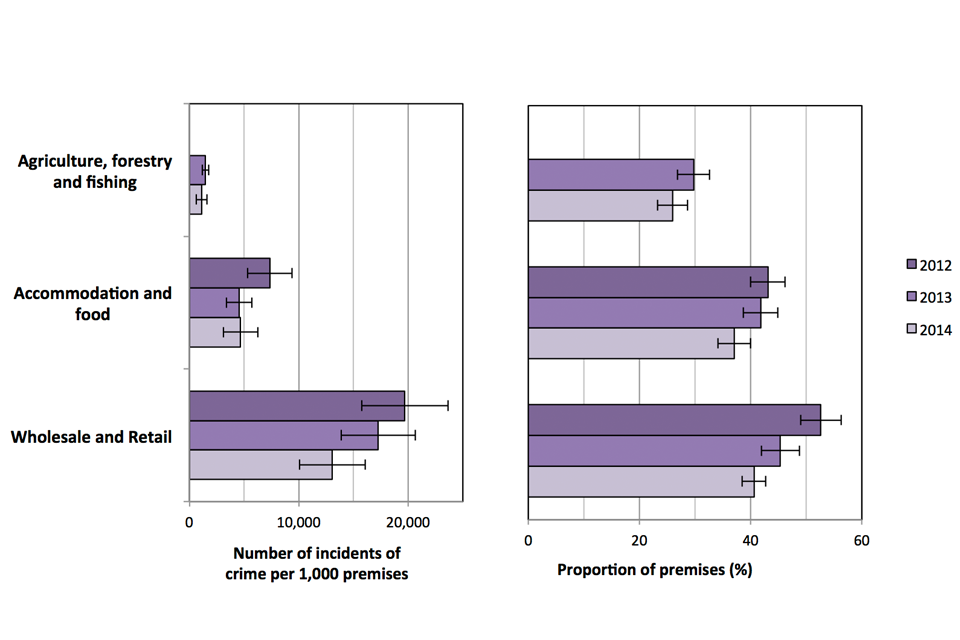

the overall crime rate against business premises in England & Wales fell in both the wholesale and retail and accommodation and food sectors between 2012 and 2014

-

the proportion of premises that were victims of crime in these two sectors also fell during the same period

-

both the rate of burglaries and the proportion of premises experiencing burglary fell in the wholesale and retail sector and the accommodation and food sector between 2012 and 2014

-

the rate of shoplifting in the wholesale and retail sector fell between 2012 and 2014. However, the average cost per incident did not change significantly

-

the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector experienced the lowest levels of crime of all the sectors surveyed in 2012, 2013 and 2014

-

levels of anti-social behaviour against business premises have remained steady over the last three years

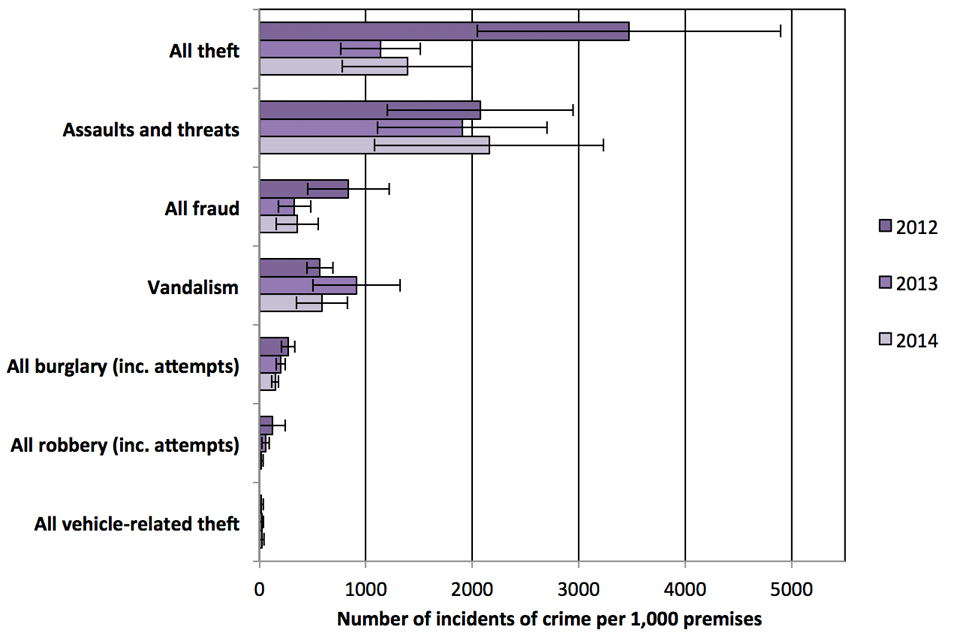

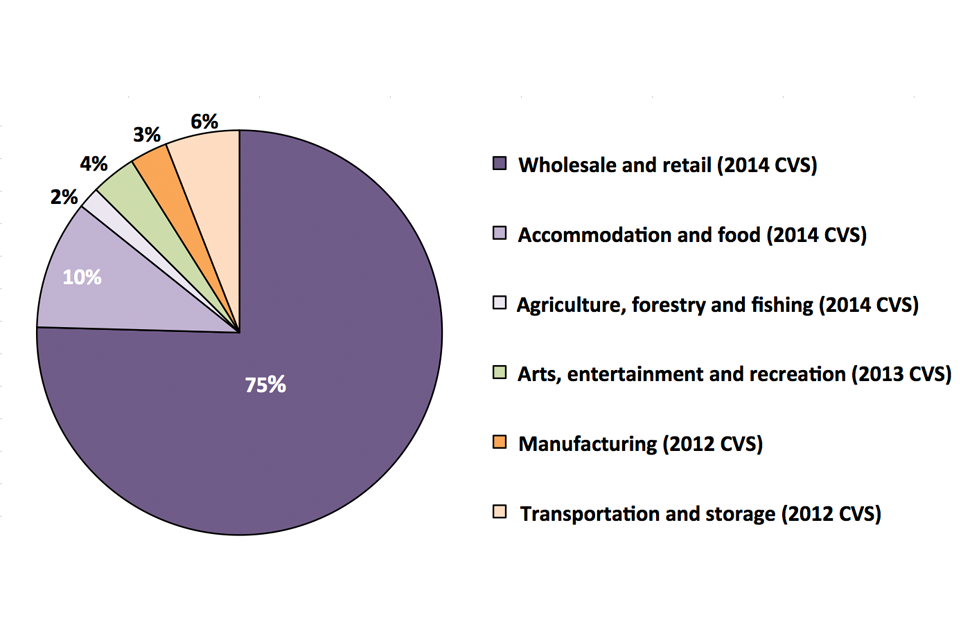

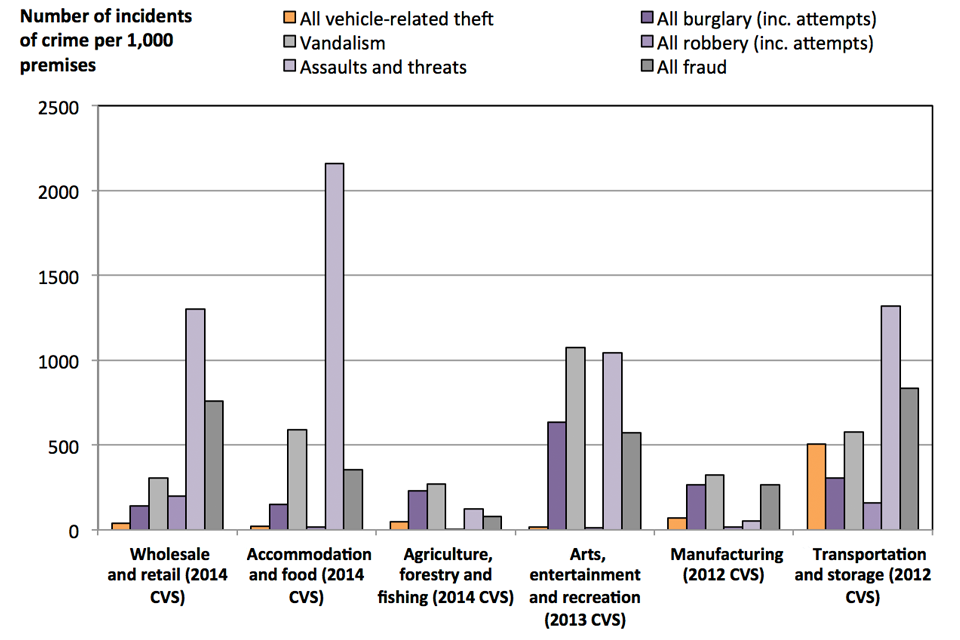

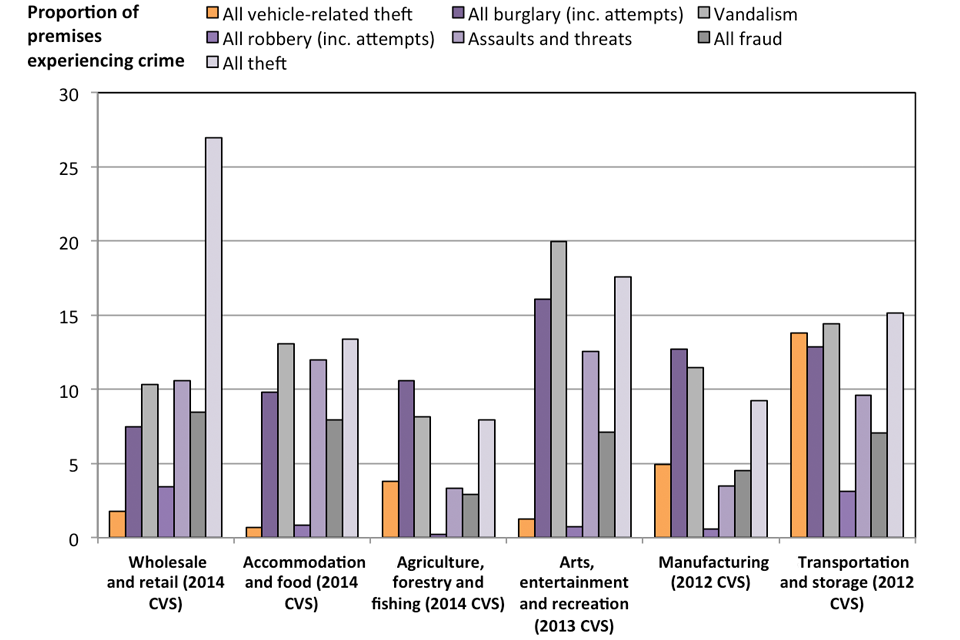

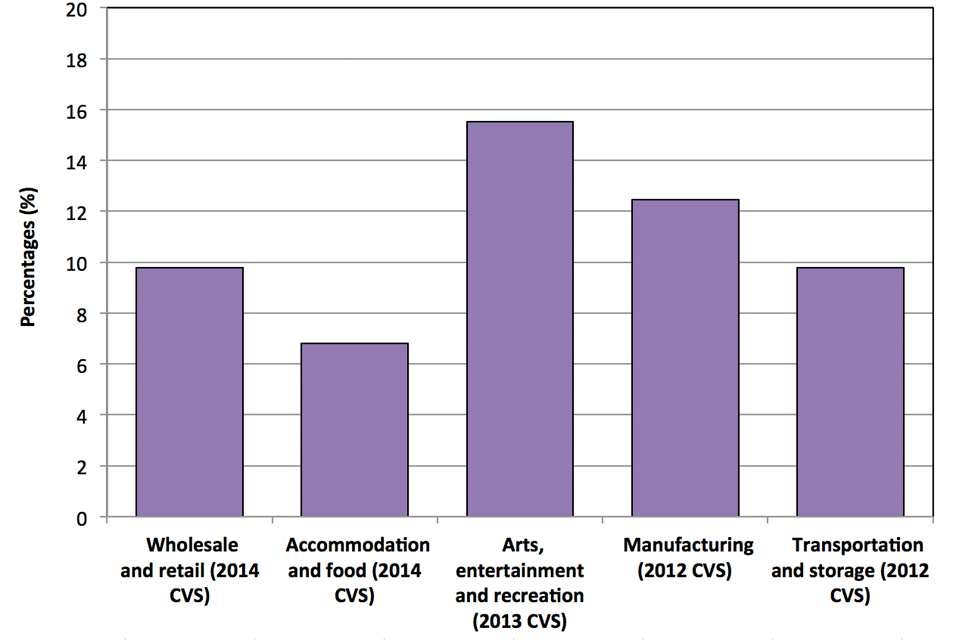

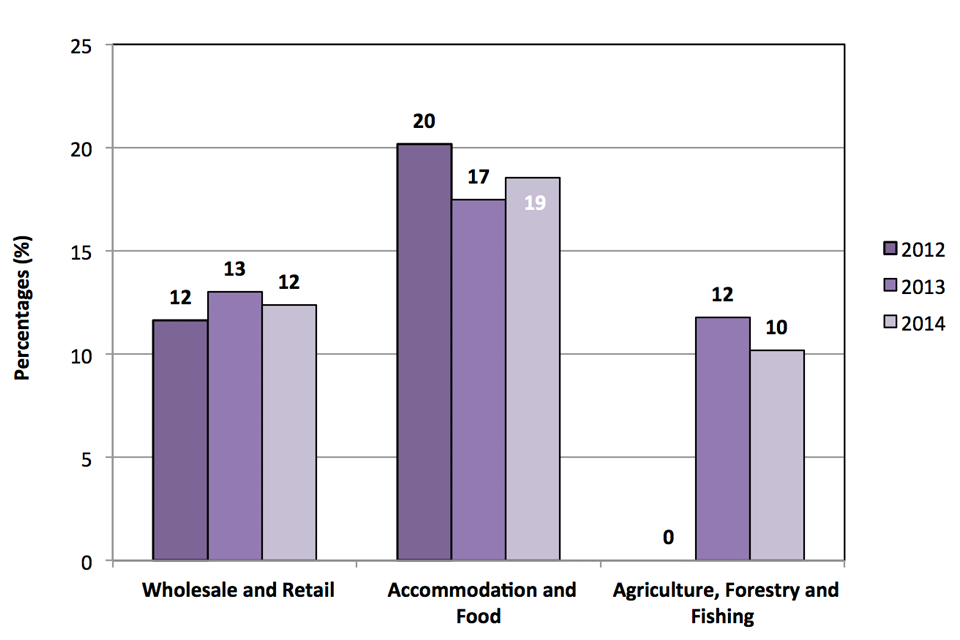

Figure E.1: Incidents of crime per 1,000 premises and proportion of premises that were victims, by sector, with 95% confidence intervals, 2012, 2013 and 2014

.

Introduction

This is the first release of data from the 2014 Commercial Victimisation Survey (CVS), a sample survey that examines the extent of crime against businesses in England and Wales. The CVS was previously run in 1994, 2002, 2012 and 2013, and is planned to be repeated annually from 2015 to 2017.

Each year a selection of industry sectors defined by the UK Standard Industrial Classification 2007 (SIC) is included in the CVS. The 2014 CVS focused on premises in three industry sectors. These were sections A (agriculture, forestry and fishing), G (wholesale and retail trade), and I (accommodation and food services activities). Between them, these three sectors accounted for just under a third of all business premises in England and Wales in 2014. In 2012 and 2013, four sectors were included in the survey. However, in 2014 the decision was taken to double the number of premises sampled in the wholesale and retail trade sector, and forego one of the other sectors. This was to allow more detailed analysis of trends in this sector due to high levels of interest in it.

All three of the sectors included in the 2014 survey were included in the 2013 survey, and two (wholesale and retail trade, and accommodation and food services activities) were also included in 2012. This means that it is now possible to look at trends in crime in these sectors in greater detail, by comparing data across the three year period. By including agriculture, forestry and fishing for a second time, comparisons can be made with 2013 for this sector. Decisions in relation to which sectors should be included were made following discussions with the CVS Steering Group, and in response to user needs. The sectors covered in future surveys will be decided in the same way, and we welcome all suggestions and feedback on this. If you would like to provide feedback, please email crimestats@homeoffice.gov.uk.

Trends over time and survey coverage

Although three years of data are now available for some sectors, comparisons between data from different survey years should be treated with caution due to the small sample sizes associated with each sector in the survey. In order to identify trends in business crime, changes between years need to be relatively large. It is therefore likely that true trends will only become apparent over the longer term.

It is important to note that although the Interdepartmental Business Register (IDBR), the sampling frame for the survey, covers 99 per cent of UK businesses, there will be some small businesses and recently started businesses that are not covered. As a result these will be excluded from the survey.

Terminology

Throughout the analysis presented in this bulletin, and its associated tables, there are four key measures of the extent of business crime presented. These focus on incidence i.e. the number of crimes taking place, and prevalence, i.e. the number of businesses that are victims. The main measures are as follows:

Total incidence: also referred to as the total crime count. This is the total number of incidents of crime experienced by business premises sampled from a particular sector. This is weighted (i.e. scaled-up) to represent the population of business premises as a whole.

Incidence rate:also referred to as the crime rate. This is the total number of incidents of crime, divided by the total number of business premises in that sector. The numbers are then multiplied by 1,000 to give the number of crimes per 1,000 premises, to allow the figures to be compared more easily. For example, comparing an incidence rate of 0.02 crimes per premises is generally not as easy to understand as a rate of 20 crimes per 1,000 premises.

Total prevalence: also referred to as the total victim count. This is the total number of premises that have been victims of crime. This is weighted (i.e. scaled-up) to represent the population of business premises as a whole.

Prevalence rate: also occasionally referred to as the victimisation rate. This is the total number of business premises that were victims of crimes, divided by the total number of premises in that sector. This gives the proportion of business premises that were victims.

One other measure that is presented is repeat victimisation. This is the number of times each victim (business premises) has experienced a particular crime. It is calculated by dividing the total number of crimes by the total number of premises that were victims. It is different from the incidence rate, which divides the total number of crimes by the total number of premises (i.e. including victims and non-victims).

Significance testing and confidence intervals

To analyse the responses to a sample survey such as the CVS, it is important to take into account the level of uncertainty introduced by using a sample, instead of the whole population of business premises in England and Wales.

To compare levels of crime in different years, statistical significance testing was carried out on the measures of crime described above. This technique is used to determine whether an observed difference is likely to be genuine rather than due to chance. Unless otherwise stated, all significance testing has been done at the 95% level, as is common for many surveys.

95% confidence intervals (error margins) have also been constructed. This is another statistical tool, closely related to significance testing. Where confidence intervals around two numbers do not overlap, the difference between the values is statistically significant. It is important to note that the opposite is not always true, i.e. overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance. To determine whether differences were statistically significant in such cases, formal significance testing was used. For further detail on these statistical tools, see the technical annex.

Data tables

The 2014 CVS headline tables include breakdowns, by sector and size band, of the following:

- the total number of incidents of crime (incidence, or crime count)

- the number of incidents of crime per 1,000 premises (incidence rate, or crime rate)

- the total number of victims of crime (prevalence, or victim count)

- the proportion of premises that experienced crime (prevalence rate, or victimisation rate)

The 2014 CVS comparison tables include comparisons of data from the 2014 CVS to data from the 2013 and 2012 CVS, for incidence rates, prevalence rates, reporting rates, organised crime perception rates and average numbers of incidents per victim. Statistically significant year-on-year changes are highlighted, and confidence intervals for the incidence and prevalence (by crime type) are also given.

The 2014 CVS anti-social behaviour, perceptions of policing and online crime tables show data discussed in chapter 5. Methodology tables are also provided.

Fact sheets and infographic

Summaries of the key findings from the 2014 CVS are available sector-specific fact sheets for the wholesale & retail, accommodation & food and agriculture, forestry & fishing sectors. The 2014 CVS infographic provides a visual summary of the key findings for all three sectors.

Further information

The dates of forthcoming publications are pre-announced and can be found via the gov.uk statistics release calendar. For further information about the Commercial Victimisation Survey please email crimestats@homeoffice.gov.uk.

Home Office Responsible Statistician

David Blunt, Chief Statistician and Head of Profession for Statistics Contact via crimestats@homeoffice.gov.uk.

This statistical release is produced to the highest professional standards and is free from political interference. It has been produced by statisticians working in the Home Office Statistics Unit in accordance with the Home Office’s Statement of Compliance with the Code of Practice for Official Statistics, which covers Home Office policy on revisions and other matters. The Home Office Statistics Unit works under the direct line management of the Home Office Chief Statistician, who reports to the National Statistician with respect to all professional statistical matters.

1. Crime against wholesale and retail premises

1.0 Introduction

In the 2014 Commercial Victimisation Survey (CVS), 2,109 respondents from premises in the wholesale and retail sector were asked if they had experienced any of a range of crime types in the 12 months prior to interview and, if so, how many incidents of crime had been experienced.

The wholesale and retail sector has now been included in the CVS for three years, so we are able to compare figures over this period. Most of the comparisons presented in this chapter are of 2014 against 2012 findings, as the most prominent changes in crime against this sector occurred over the two-year period. The relatively small sample size of the survey makes detecting changes between adjacent years more difficult. More information will become available in future years as longer trends develop. Comparisons with 2012 and 2013 figures, with results of statistical significance testing and confidence intervals, are presented in the accompanying 2014 CVS Comparison Tables. Premises from the wholesale and retail sector were previously also included in the 1994 and 2002 Commercial Victimisation Surveys. Due to changes in methodology between surveys and changes to the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC), estimates for this sector from the 2014 CVS can only be directly compared with the 2013 and 2012 surveys.

The 2014 CVS also collected information on areas such as online crime, organised crime, cost of crime, and reporting rates (to the police). These findings, and information on repeat victimisation (average number of crimes per victim), are presented here.

Most businesses from this sector are retailers (1,648 respondents). Wholesalers and motor vehicle trade and repair businesses are also included.

2014 CVS estimates for this sector are based on roughly twice the number of premises sampled for the 2012 and 2013 CVS. This followed extensive consultation with users and the CVS steering group, which highlighted a clear interest in finding out more about crime against this sector. Data are weighted to ensure that the sample is representative of wholesale and retail businesses in England and Wales as a whole. Results for all CVS sectors, including the wholesale and retail sector, are presented in the accompanying 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Please refer to the introduction to this report for further information about the contents of data tables accompanying the publication.

1.1 Key findings

Crime in the wholesale and retail sector fell significantly between 2012 and 2014.

The number of incidents experienced by this sector fell from 7.7 million in 2012 to 4.1 million in 2014. This fall was statistically significant, and was largely driven by falls in shoplifting.

Shoplifting (customer theft) has fallen significantly compared with 2012.

Compared with 2012, the 2014 CVS shows that the number of thefts in the wholesale and retail sector has fallen by around a third, from 15,836 to 10,319 incidents per 1,000 premises. Within this, theft by customers (shoplifting) has fallen by 3,749 incidents per 1,000 premises, from 10,445 to 6,695 incidents per 1,000 premises. Both falls are statistically significant.

The proportion of premises experiencing crime in this sector also fell significantly.

The proportion of wholesale and retail premises that were victimised has fallen from 53 per cent in 2012 to 45 per cent in 2013 and to 41 per cent in 2014. Both decreases are statistically significant and are driven by statistically significant falls for a wide range of crime types.

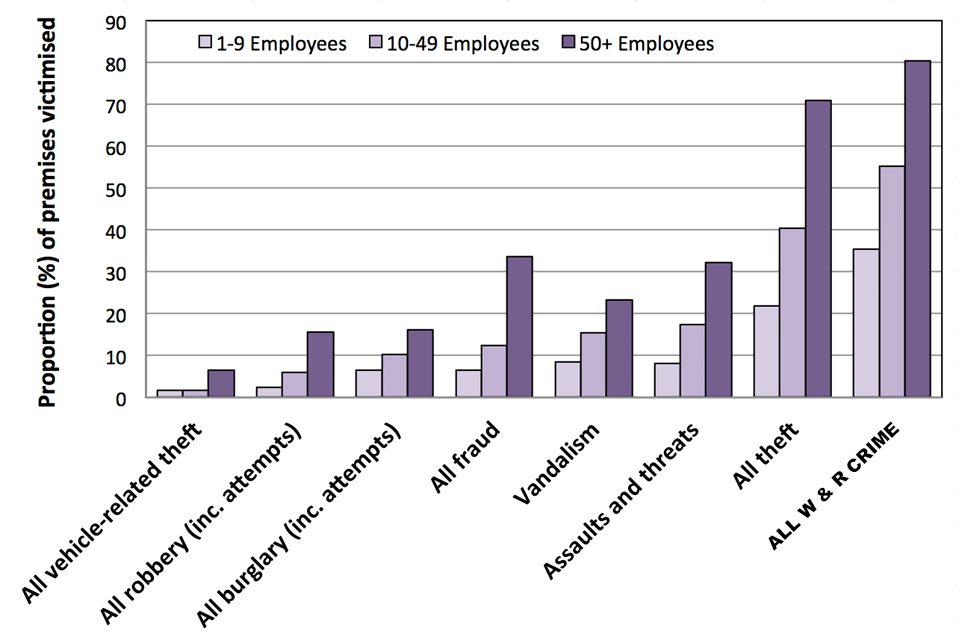

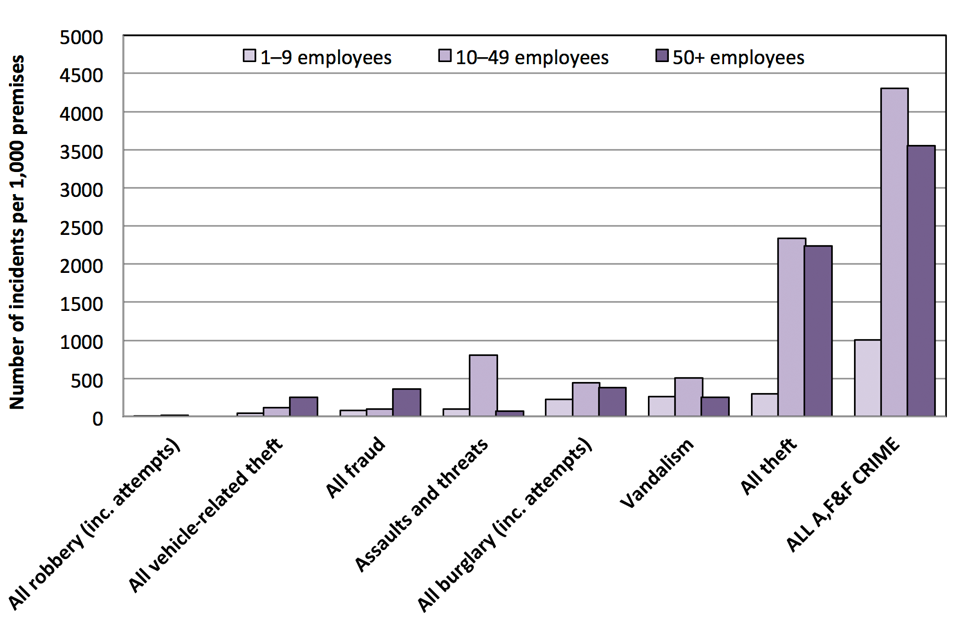

Larger businesses in this sector experienced higher crime rates and prevalence rates.

In 2014, those premises in the wholesale and retail sector with 50 or more employees experienced six times more crimes on average than those with 10-49 employees, and 40 times more than those with 1-9 employees. Similarly, higher proportions of premises with 50 or more employees were victims of crime (80%), than those premises with 10-49 employees (55%) or 1-9 employees (35%).

1.2 Extent of crime against wholesale and retail premises

Table 1.1: Experiences of crime in the last 12 months, wholesale and retail sector, 2014 cvs

| Crime type | Number of crimes (000s) | Number of crimes per 1,000 premises | Number of victims (000s of premises) | % of premises experiencing | Average number of crimes experienced by each victim (premises) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All burglary (inc. attempts) | 45 | 143 | 24 | 8 | 2 |

| Vandalism | 97 | 308 | 33 | 10 | 3 |

| All vehicle-related theft | 13 | 40 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| All robbery (inc. attempts) | 63 | 199 | 11 | 3 | 6 |

| Assaults and threats | 410 | 1,301 | 34 | 11 | 12 |

| All theft | 3,255 | 10,319 | 85 | 27 | 38 |

| Thefts by customers | 2,112 | 6,695 | 63 | 20 | 33 |

| Thefts by employees | 69 | 219 | 11 | 3 | 6 |

| Thefts by others | 64 | 202 | 7 | 2 | 10 |

| Thefts by unknown persons | 1,010 | 3,202 | 25 | 8 | 41 |

| All fraud | 240 | 761 | 27 | 8 | 9 |

| All wholesale and retail crime | 4,123 | 13,070 | 128 | 41 | 32 |

Unweighted base: 2,109 premises

Table 1.2: Changes in crime in the wholesale and retail sector, 2014 compared with 2012 CVS

| Crime type | Change in number of crimes per 1,000 premises | Change in % of premises experiencing | Change in average number of crimes experienced by each victim (premises) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All burglary (inc. attempts) | -194 * | -4% * | -1 |

| Vandalism | -177 | -6% * | -0.07 |

| All vehicle-related theft | -31 | -3% * | +1 |

| All robbery (inc. attempts) | -434 | +1% | - |

| Assaults and threats | +127 | +0.4% | +1 |

| All theft | -5,517 * | -5% * | -12 |

| Thefts by customers | -3,749 * | -1% | -16 * |

| Thefts by employees | -424 | -1% | -7 |

| Thefts by others | +64 | +0.1% | +3 |

| Thefts by unknown persons | -1,407 | -5% * | +6 |

| All fraud | -406 | -4% * | -0.3 |

| All wholesale and retail crime | -6,630 * | -12% * | -5 |

Table notes

- columns related to victims may not sum to the totals shown for all crime: this is because one premises can be a victim of more than one type of crime; other columns may not sum exactly to the total shown due to rounding

- statistically significant changes are indicated with asterisks (*); other changes are not significant;

a hyphen (-) indicates that a figure is not shown because its unweighted base is fewer than 50 respondents

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables and 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

Wholesale and retail premises experienced 4.1 million crimes in the year prior to interview. Of these, over three quarters of incidents were thefts and, specifically, over half (51%) of the 4.1 million incidents were theft by customers (i.e. shoplifting, 2.1 million incidents). A further one million incidents (24%) were due to theft by unknown persons. These are similar proportions to 2013 and 2012, when theft by customers accounted for 55 and 53 per cent of all incidents against wholesale and retail premises, respectively, and theft by unknown persons accounted for 21 and 23 per cent, respectively.

The breakdown of the theft figures is affected by the fact that it is not always possible to identify the offender. It is likely that some of the thefts by unknown persons were committed by customers. Over the past 3 years, the proportion of incidents due to thefts by customers or by unknown persons has remained at 76 per cent of the total number of incidents experienced by wholesale and retail premises.

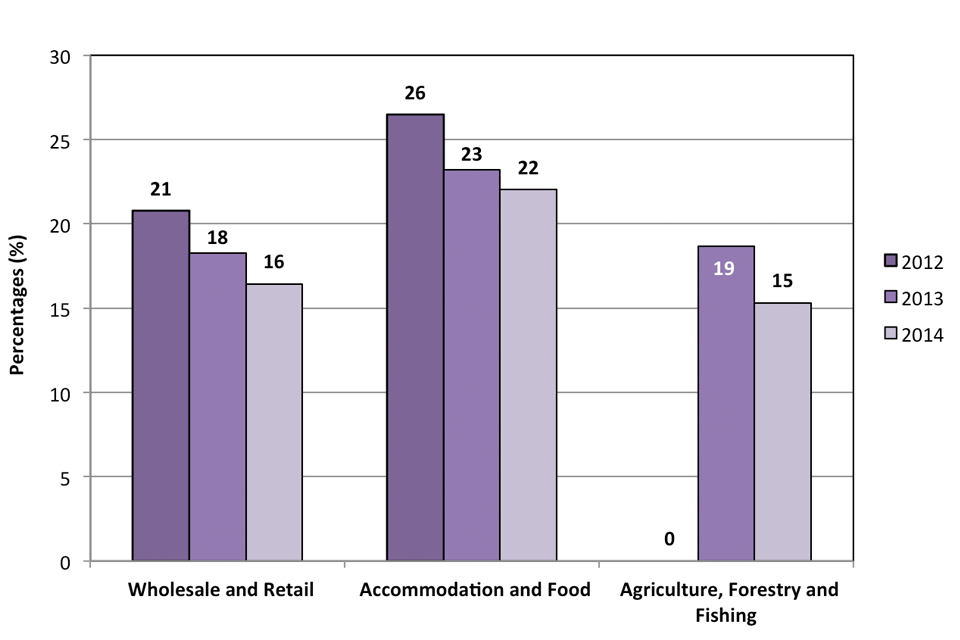

Number of incidents per 1,000 premises

In 2014, thefts by customers fell significantly compared with 2012, but still accounted for the largest number of all crime types against the wholesale and retail sector, with 2,112 incidents in the 12 months prior to interview (6,695 incidents per 1,000 premises), see Tables 1.1 and 1.2.

The total number of incidents of crime per 1,000 premises also fell significantly compared with 2012, largely due to the above fall in thefts by customers. Further comparisons to 2012 and 2013 CVS figures are published in table “W&R” in the 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

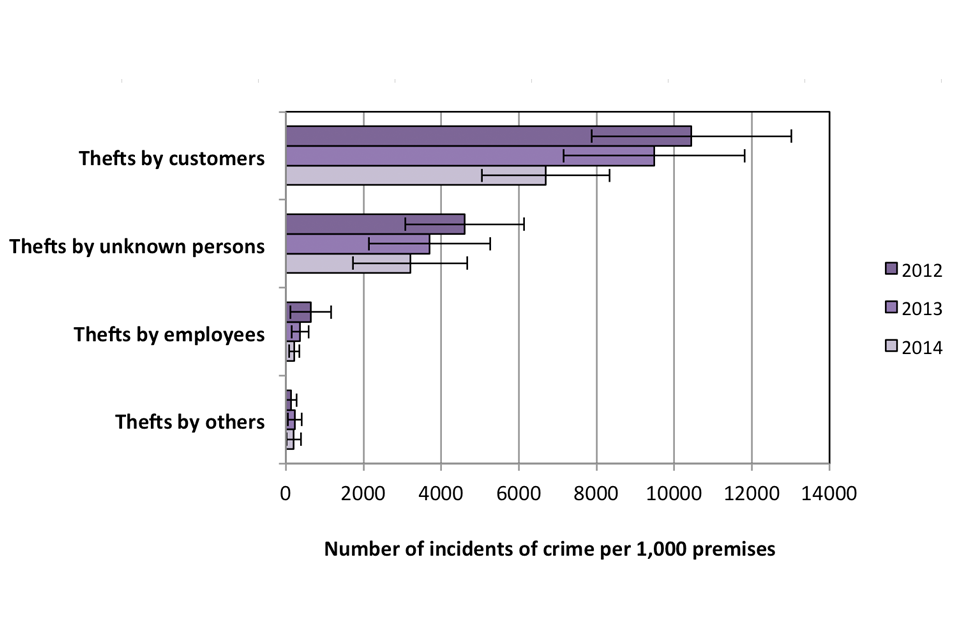

Figure 1.1: Incidents of theft per 1,000 premises, by type, experienced by wholesale and retail premises in the last 12 months, with 95% confidence intervals, 2012, 2013 and 2014 CVS

.

Chart notes

- theft is presented separately due to its large scale relative to the other crime types

- error bars represent 95% confidence intervals; while non-overlapping confidence intervals usually indicate a statistically significant difference, overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

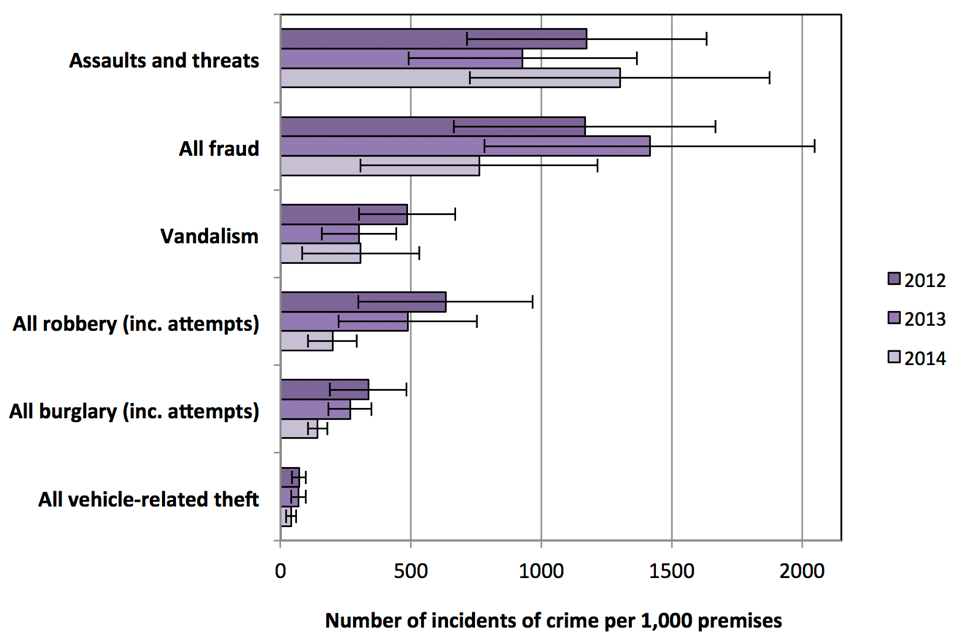

Figure 1.2: Incidents of crime per 1,000 premises (excl. thefts) experienced by wholesale and retail premises in the last 12 months, with 95% confidence intervals, 2012, 2013 and 2014 CVS

.

Chart notes

- theft is presented separately due to its large scale relative to the other crime types

- error bars represent 95% confidence intervals; while non-overlapping confidence intervals usually indicate a statistically significant difference, overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

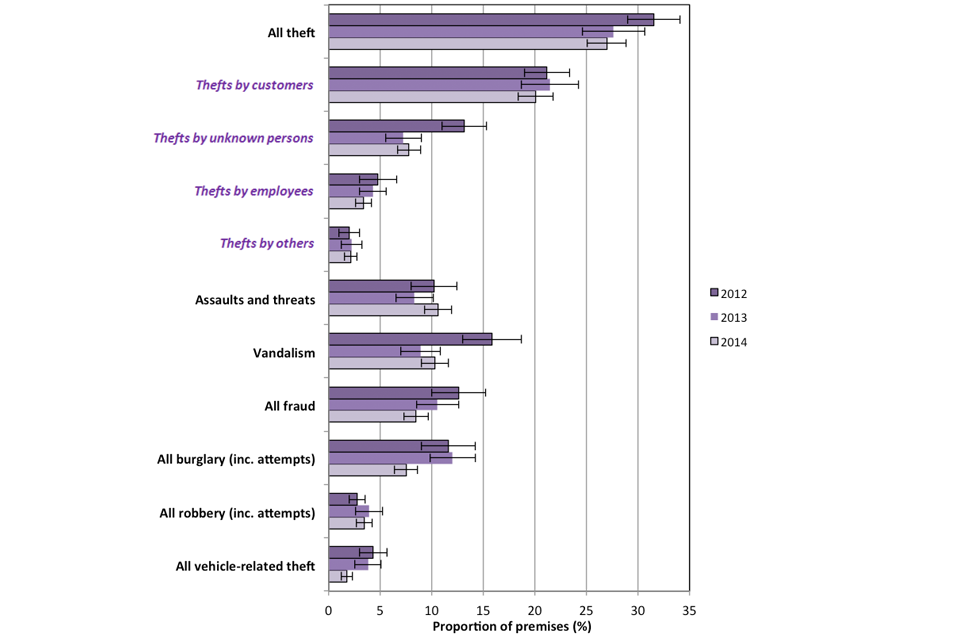

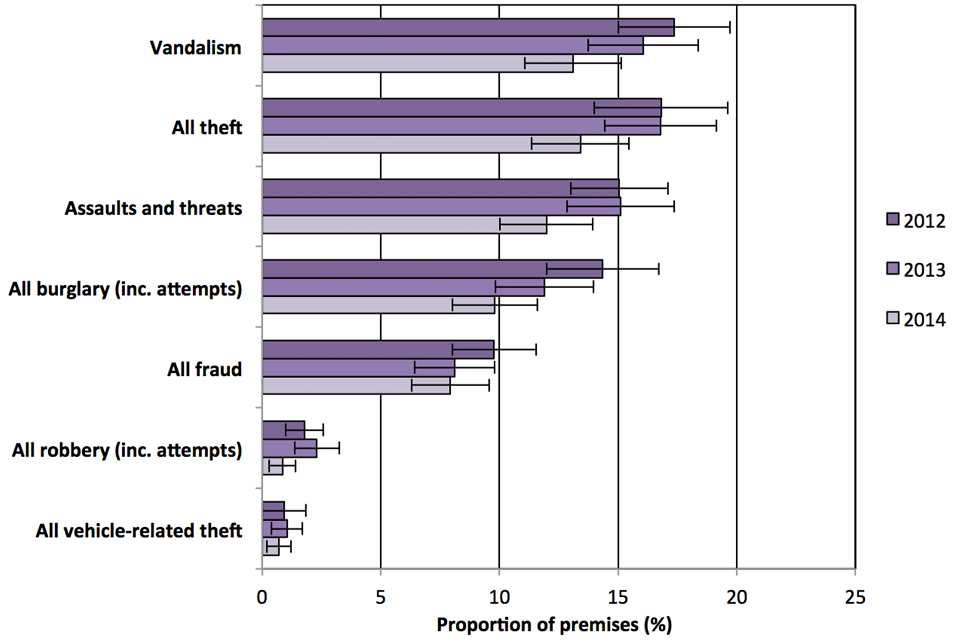

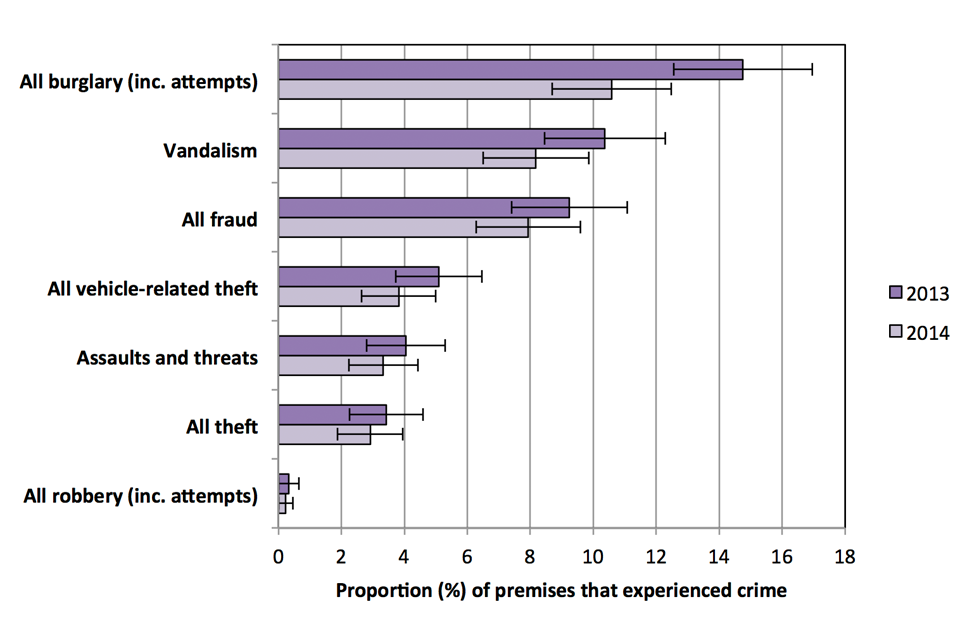

Proportions of premises that experienced a crime

The level of victimisation in the wholesale and retail sector was relatively high compared with the other sectors surveyed in 2014, but has fallen significantly over the past two years. In 2014 just over two-fifths (41%) of premises in this sector experienced a crime in the 12 months prior to interview, compared with 45% in 2013 and more than half (53%) in 2012. In both years the fall was statistically significant.

One-fifth (20%) of premises experienced theft by customers, around one-tenth (11%) experienced an assault or threat and 10 per cent experienced vandalism; these crime types showed the highest levels of victimisation in the wholesale and retail sector in 2014.

Compared with 2012, there were many statistically significant falls in the proportion of premises in this sector experiencing a variety of crime types (Table 1.3). Changes in victimisation levels compared with 2012 and 2013 can be found in the 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

Figure 1.3: Proportion of wholesale and retail premises that experienced crime in the last 12 months, by type, with associated 95% confidence intervals, 2012, 2013 and 2014 CVS

.

Chart notes

- thefts by unknown persons, thefts by employees, thefts by customers and thefts by others are subsets of all thefts

- error bars represent 95% confidence intervals; while non-overlapping confidence intervals usually indicate a statistically significant difference, overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

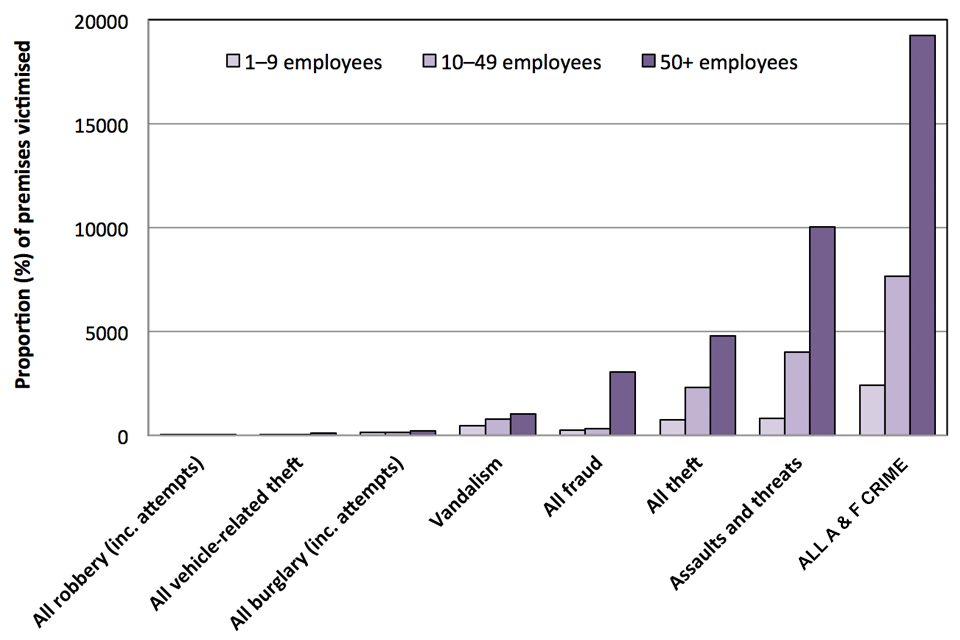

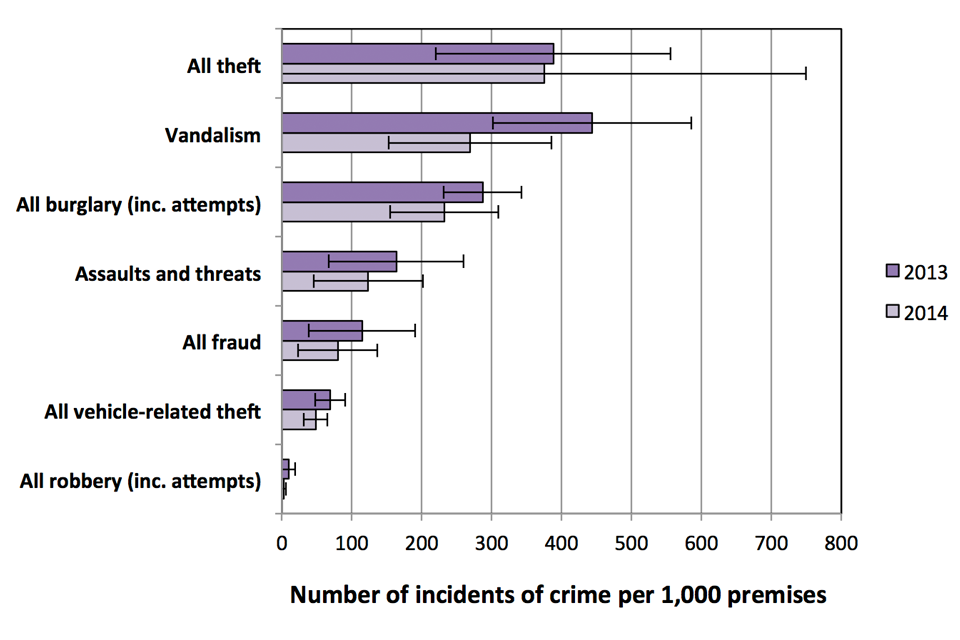

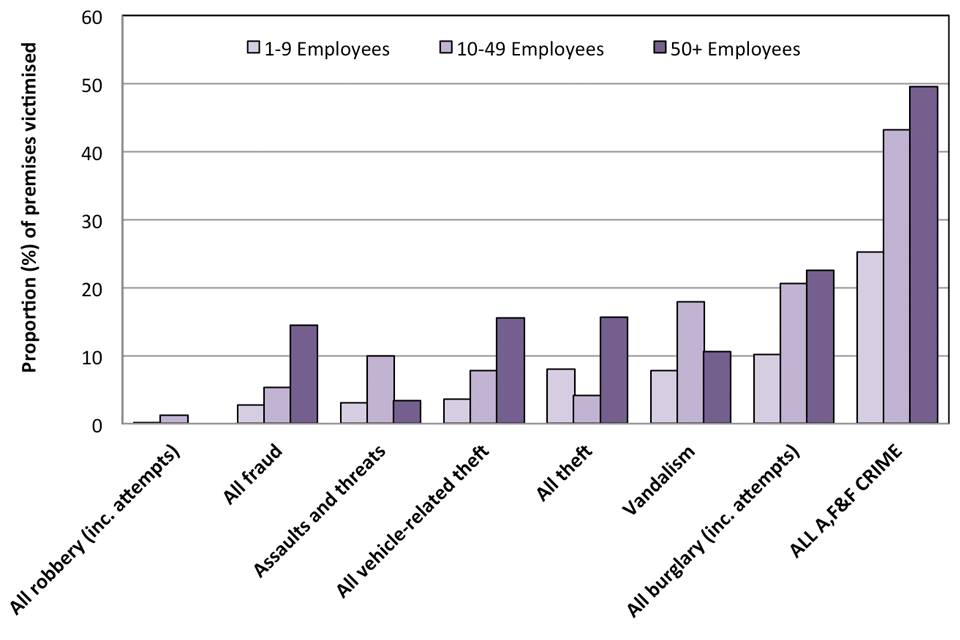

Incidence and prevalence rates by business size

As previously shown by the 2012 and 2013 CVS, incidence rates of crime (i.e. number of incidents per 1,000 premises) are higher for premises with more employees. In both 2013 and 2014, large businesses had significantly higher incidence rates. This pattern was particularly noticeable in the incidence rates of theft. The overall number of thefts per 1,000 premises with 50 or more employees was 21 times higher than those for premises with fewer than 50 employees in 2014.

Higher rates of (i) fraud and (ii) assault or threat against larger businesses also contributed to the differences in crime rates by business size. Together with theft, these were the three most common crime types experienced in this sector in the past year (Table 1.4).

Table 1.4: Number of incidents per 1,000 premises for most common crime types, by premises size, wholesale and retail sector, 2014 CVS

| England and Wales | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crime type | 1 to 9 employees | 10 to 49 employees | 50+ employees | All premises |

| All theft | 2,546 | 22,869 | 129,586 | 10,319 |

| Assaults and threats | 757 | 1,496 | 14,050 | 1,301 |

| All fraud | 338 | 747 | 11,737 | 761 |

| All wholesale and retail crime | 4,039 | 26,277 | 160,510 | 13,070 |

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

A breakdown of prevalence rates by size (Figure 1.4) presents a similar picture. The proportions of premises that experienced a crime in the 12 months prior to interview also increased with the number of employees at the premises, and were highest for theft, but varied less than the numbers of incidents per 1,000 premises.

Figure 1.4: Proportion of wholesale and retail premises that experienced crime in the last 12 months, by crime type and number of employees at premises, 2014 CVS

.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

Average number of incidents of crime per victim (premises)

The average number of incidents of crime per victim is a measure of repeat victimisation, representing the average number of times each victim has experienced a particular crime. It is calculated by dividing the total number of crimes by the total number of victims. Changes in the average number of incidents per victim depend on both the number of incidents and the number of victims. For example, if the number of incidents increases, but the number of victims increases by more, this measure will actually fall. This measure can reveal some interesting trends in crime.

Overall, each victim of crime in the wholesale and retail sector experienced an average of 32 incidents in the last year. The highest average numbers of incidents per victim were for thefts, with each theft victim experiencing an average of 38 thefts in the last year. Looking at different types of theft, there were 33 incidents per victim of theft by customers, and 41 incidents per victim of theft by unknown persons.

Theft by customers (33 incidents per victim) has fallen from 49 incidents per victim in 2012 and 44 incidents per victim in 2013. The decrease over the two years since 2012 is statistically significant, although the decrease from 2013 alone is not. Theft by unknown persons (41 incidents per victim) has fallen compared with 2013 (from an average of 51 incidents per victim), but risen compared with 2012 (from an average of 35 incidents per victim); neither change is statistically significant.

1.3 Other results from the survey

This section includes findings on shoplifting (theft by customers) and its cost, online crime, reporting rates and organised crime.

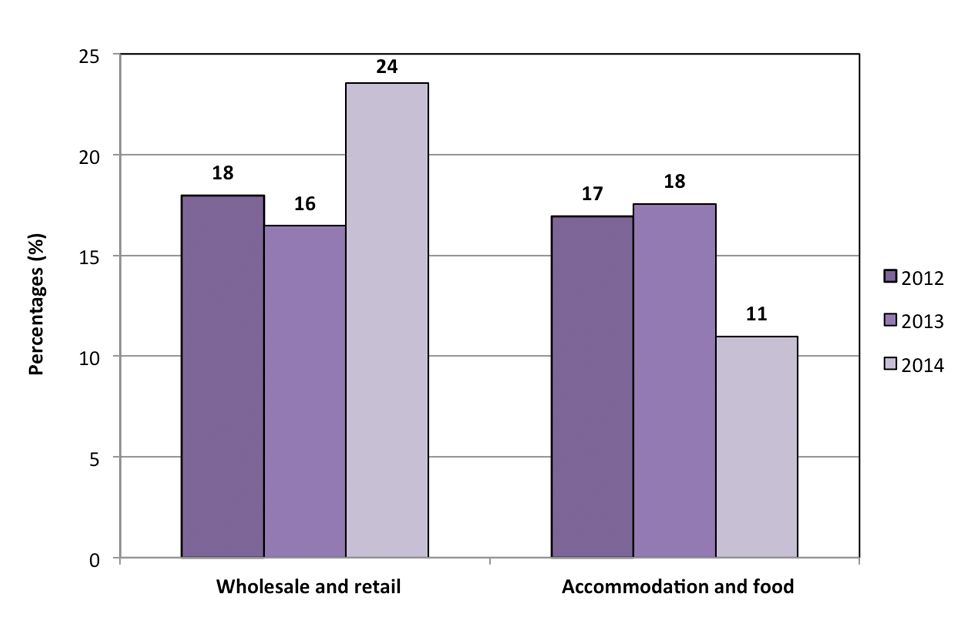

Shoplifting

The 2014 CVS reveals that shoplifting (theft by customers) made up 51% of all incidents of crime in the wholesale and retail sector in 2014. It was the most common crime type, with 6,695 incidents per 1,000 premises, although this has fallen significantly since 2012 (by 3,749 incidents per 1,000 premises).

In 2014, 20 per cent of premises experienced shoplifting, which was broadly similar to 2012. The average number of shoplifting incidents per victim has fallen significantly, down to 33 incidents per victim, compared with 49 incidents per victim in 2012.

It is important to note that the CVS may underestimate the volume of shoplifting, as the “theft by unknown persons” category may also contain a large proportion of unidentified customer thefts. However, it is likely that this will have been the case for each of the years from 2012 to 2014, so this should not affect the overall direction of the trend.

These findings are comparable[footnote 1] to findings from the British Retail Consortium (BRC) Retail Crime Survey 2014, which also showed that theft by customers made up the majority of crime against retailers (81%). According to the BRC survey, customer theft has decreased slightly in the past year from 631,391 incidents in 2012/13 to 552,069 in 2013/14. This is also consistent with the trend shown by the 2014 CVS, where customer theft fell from 3.25 million incidents in 2013 to 2.11 million in 2014.

By contrast, the latest police recorded crime statistics published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show an increase in shoplifting. The number of shoplifting offences recorded by the police rose from 317,047 offences in the year ending December 2013 to 325,504 offences in the year to December 2014, an increase of 3 per cent. However, the increase in the number of offences recorded by the police could be due to an increase in the proportion of shoplifting incidents that come to the attention of police, or changes to police recording practices. This is supported by the fact that the police recorded crime figures are lower than those reported by the CVS and BRC.

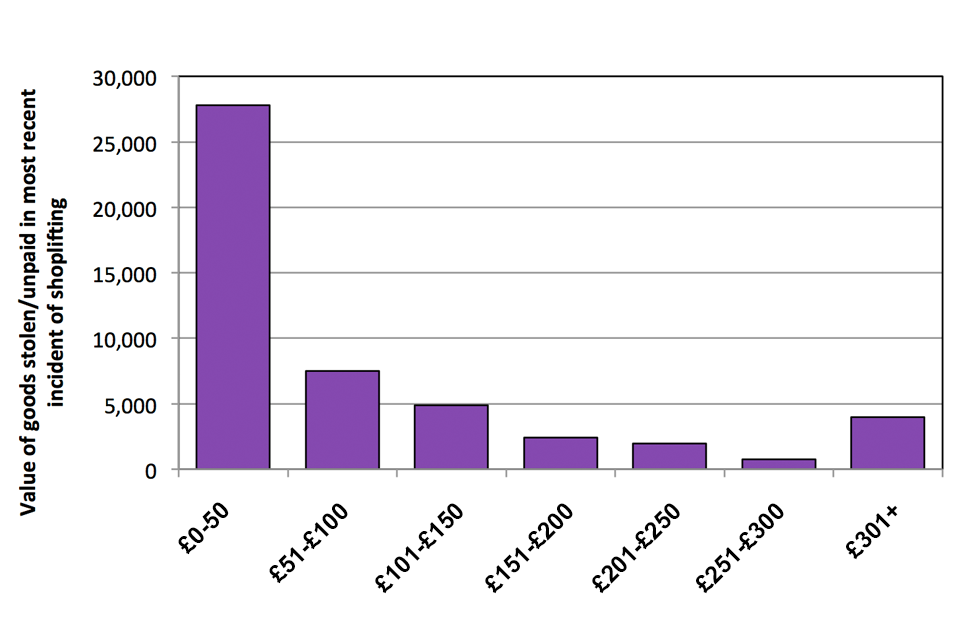

The 2014 CVS estimates that the mean cost of shoplifting per incident in 2014 was £126. This is a fall compared with both 2012 (£157) and 2013 (£177) CVS data, though neither change is statistically significant. Meanwhile the number of incidents of shoplifting has fallen significantly between 2012 and 2014 (Figure 1.5). For more information on how the costs of shoplifting are calculated, please see the technical annex.

These findings contrast those reported in the BRC Retail Crime Survey 2014, which reported a 36% increase in the average cost of theft by customers between 2012/13 and 2013/14, and a 4% fall in the volume of shoplifting. The CVS suggests that while the volume of shoplifting may be falling, the average cost is not increasing, and if anything may also be falling.

Figure 1.5: Incidents of theft by customers per 1,000 premises and mean value of items stolen/unpaid per incident, wholesale and retail sector, 2012, 2013 and 2014 CVS

.

Chart notes

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. While non-overlapping confidence intervals usually indicate a statistically significant difference, overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS survey responses and 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Comparing the mean, median and maximum costs of the most recent shoplifting incident experienced by respondents in the 12 months prior to interview (Table 1.5) reveals that most incidents of shoplifting are fairly low-cost, although there are a small number of incidents where high-value items have been taken in each of the last three years. This can be seen from the fact that the mean is higher than the median for each year; for this reason, when looking at the costs of shoplifting it is often more informative to consider the median cost rather than the mean. This pattern is also illustrated by figure 1.6, which shows that the majority of shoplifting incidents in 2014 involved relatively low value items being stolen.

Table 1.5: Value of items stolen/unpaid in the most recent incident of shoplifting experienced in the 12 months prior to interview, wholesale and retail sector, 2012, 2013 and 2014 CVS

| Value of items stolen/unpaid | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value of items stolen/unpaid | £158 | £177 | £126 |

| Median value of items stolen/unpaid | £35 | £50 | £40 |

| Maximum value of items stolen/unpaid | £20,000 | £3,000 | £2,500 |

| Unweighted base | 213 | 207 | 508 |

Table note

This analysis excludes two cases where the numbers of crimes reported were so large that it was judged that they were very likely to be erroneous or that the respondents had misunderstood some questions. For further details please see the methodology section of the technical annex.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS survey responses.

Figure 1.6: Incidents of shoplifting grouped by value of goods stolen/unpaid, based on the most recent incident experienced by each premises, wholesale & retail sector, 2014 CVS

.

Unweighted base: 508 premises.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS survey responses.

Supermarkets experienced significantly higher incidence and prevalence rates for shoplifting, compared with the sector as a whole. In 2014 supermarkets experienced 63,158 incidents of shoplifting per 1,000 premises, compared with 6,695 incidents per 1,000 premises across the wholesale and retail sector. Similarly, 64 per cent of supermarkets were victims of shoplifting, compared with 20 per cent of all wholesale and retail premises. Shoplifting from supermarkets accounts for one third (33%) of all customer theft in the wholesale and retail sector, although retail supermarket premises account for only 3% of all premises in this sector.

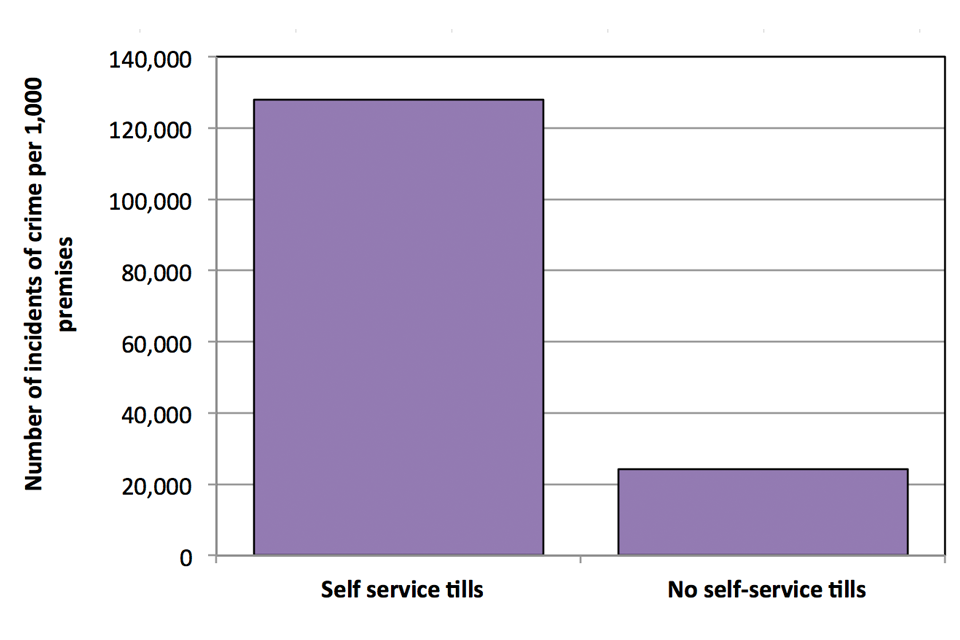

Shoplifting and self-service tills

The 2014 CVS included a new question, asking retail supermarket premises whether they had any self service tills. The responses to this question give an estimate of how many supermarkets have self-service tills, and allow a comparison of shoplifting rates for premises with and without self-service tills.

The survey found that self-service tills were found in fewer than half (38%) of supermarkets. However, the survey also suggested that supermarkets with self-service tills were significantly more likely to experience shoplifting than those without, with 86 per cent of those with self-service tills being victims, compared with 52 per cent of those without. Those with self-service tills also experienced significantly more crimes (figure 1.7).

These findings suggest a link between self-service tills and higher levels of shoplifting. However, it is important to note that this possible link does not show that self-service tills cause higher levels of shoplifting. Large supermarket premises are much more likely to contain self-service tills (89% contain them) than small ones (8%), so the size of the supermarket may be the important factor, rather than the presence of self-service tills. Other research into the effect of self-service tills on shoplifting has not demonstrated a clear link between the two, but does suggest that they may generate some additional crime [footnote 2].

Figure 1.7: Rates of shoplifting for supermarkets with, and without, self-service tills

.

Unweighted base: 187 premises.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS survey responses.

As shown in table 1.4 and figure 1.4, large premises in this sector are more likely to be victims of crime, and also experience more crimes (especially thefts) than smaller premises. To truly establish a link between self-service tills and shoplifting, it would be necessary to analyse the link between self-service tills and shoplifting independently of other factors. For this analysis to be robust, more data would be needed, which may become available from future surveys.

Online crime

Online crime covers a range of crime types carried out over computer networks. Respondents from this sector, who used computers at their premises, were asked about their experience of various types of online crime. See the technical annex for the online crime types covered in the survey and for further details of online crime. It is important to bear in mind that respondents were only asked about online crimes affecting the premises. Many online crimes may affect only head offices and will not have been picked up by the survey.

Half of the respondents from the wholesale and retail sector were asked whether computers were used at the premises. Those who used computers were then asked about their business’s experience of online crime. In the wholesale and retail sector 85% of businesses said they used computers, compared with 84% across all the six sectors surveyed in 2012, 2013 and 2014.

The 2014 CVS estimates that there were 136,000 incidents of online crime against businesses in the wholesale and retail sector in the 12 months prior to interview. This is a notable decrease compared with 2013 (234,000 incidents), but an increase compared with 2012 (69,000 incidents). Neither change is statistically significant, reflecting the degree of uncertainty associated with the small sample. However, compared with 2012, there has been a statistically significant increase (+3%) in the proportion of premises that have experienced a computer virus.

The most commonly experienced online crimes in each of the last three years were computer viruses. In 2014 there were 118,000 incidents in the year prior to interview, making up 87 per cent of all incidents of online crime against this sector (compared with 91 per cent in 2013 and 81 per cent in 2012).

The number of online crime incidents per 1,000 premises was higher for premises with fewer employees (see table 1.7). This may suggest that smaller businesses spend less on IT security. Findings from the 2013 CVS suggest that larger businesses have a larger spend on online security.

Around 10 per cent of all wholesale and retail premises experienced at least one type of online crime in the last year, with nine per cent experiencing a virus and two per cent experiencing hacking in the 12 months prior to interview. Victimisation of the other types of online crime (such as hacking or phishing) was less widespread. Possible reasons for this are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4, which presents cross-sector CVS findings.

Table 1.6: Experiences of online crime in the last 12 months, wholesale & retail sector, 2014 CVS

| Crime type | Number of crimes (000s) | Number of crimes per 1,000 premises | Number of victims (000s of premises) | % of premises experiencing | Average number of crimes experienced by each victim (premises) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hacking | 6 | 19 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Phishing | 5 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Theft of money (online) | 5 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Theft of information (online) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Website vandalism | 2 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Computer virus | 118 | 373 | 28 | 9 | 4 |

| All online crime | 136 | 430 | 31 | 10 | 4 |

Unweighted base: 1,097 premises

Table 1.7: Numbers of online crime per 1,000 premises in the last 12 months, by number of employees at premises, wholesale & retail sector, 2014 CVS

| Crime type | 1 to 9 Employees | 10 to 49 Employees | 50+ Employees | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hacking | 22 | 6 | 13 | 19 |

| Phishing | 2 | 67 | 0 | 15 |

| Theft of money (online) | 2 | 67 | 4 | 15 |

| Theft of information (online) | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Website vandalism | 7 | 12 | 5 | 8 |

| Computer virus | 417 | 240 | 126 | 373 |

| All online crime | 449 | 398 | 148 | 430 |

| Unweighted base | 668 | 214 | 215 | 1097 |

Table notes

- columns related to victims do not sum to the totals shown for all online crime; this is because one premises can be a victim of more than one type of crime; other columns may not sum exactly to the total shown due to rounding

- since computers are used at a high proportion of premises, incidence and prevalence rates are reported relative to the total number of business premises in the sector, not only those where computers are used

- incidents of online crime are not included in the overall count of CVS crime as these questions are only asked of half the sample and there is a risk of double-counting with other crime types, such as theft or fraud

- although described here as crimes, it is worth noting that not all of these incidents would be recorded as a crime by the police; whether receiving a phishing email or being infected by virus is counted under police recorded crime depends on whether the incident was targeted at a specific victim, or any financial loss was incurred, as per the Home Office Counting Rules

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

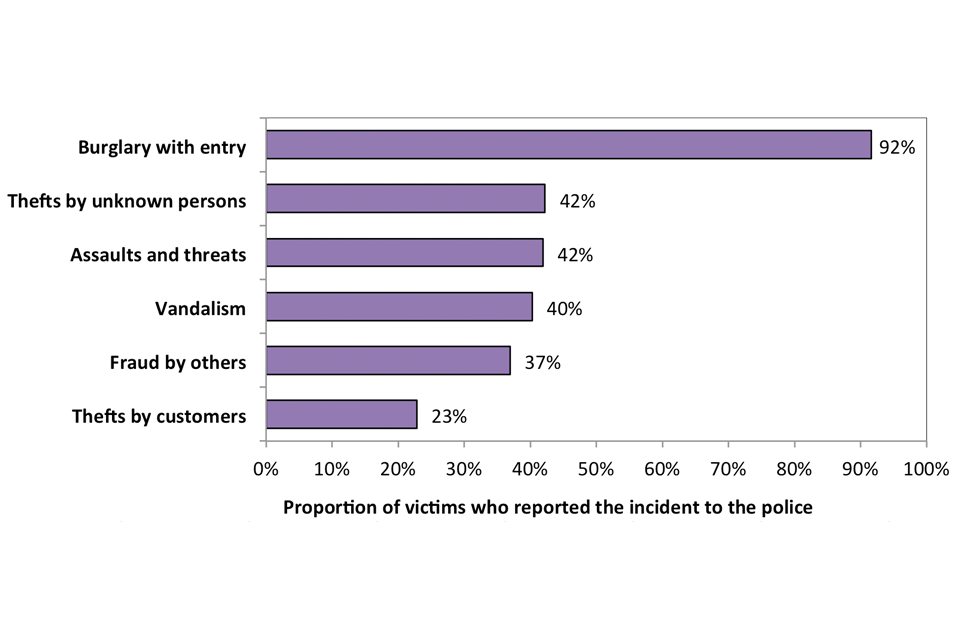

Reporting rates

The 2014 CVS asked those respondents who had experienced crime in the past year whether the police came to know about the most recent incident of each crime type experienced.

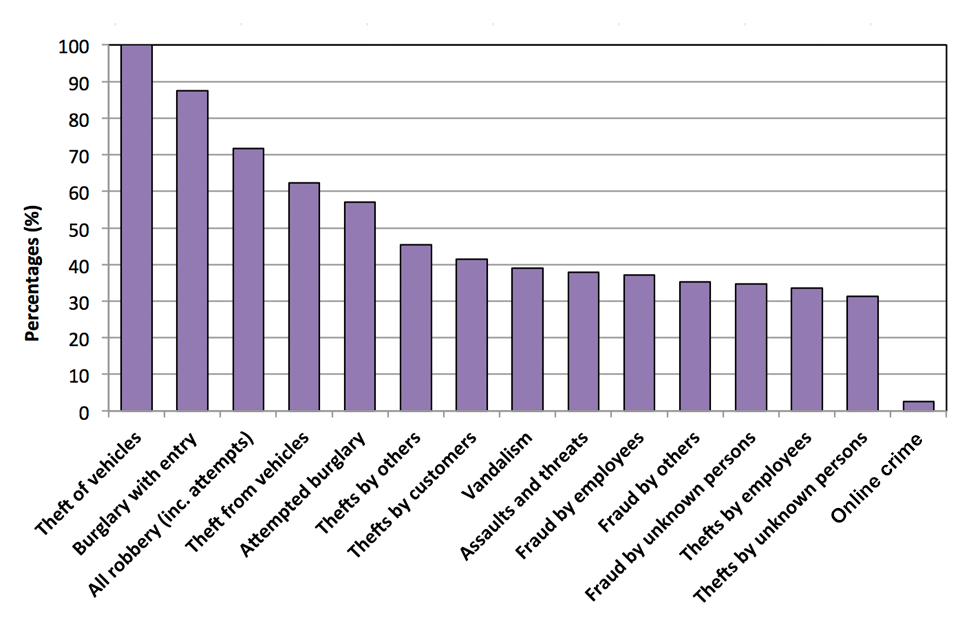

Table 1.8 compares 2014 CVS reporting rates to 2013 and 2012. Comparisons should be treated with some caution given their variability from one year to the next in many cases.

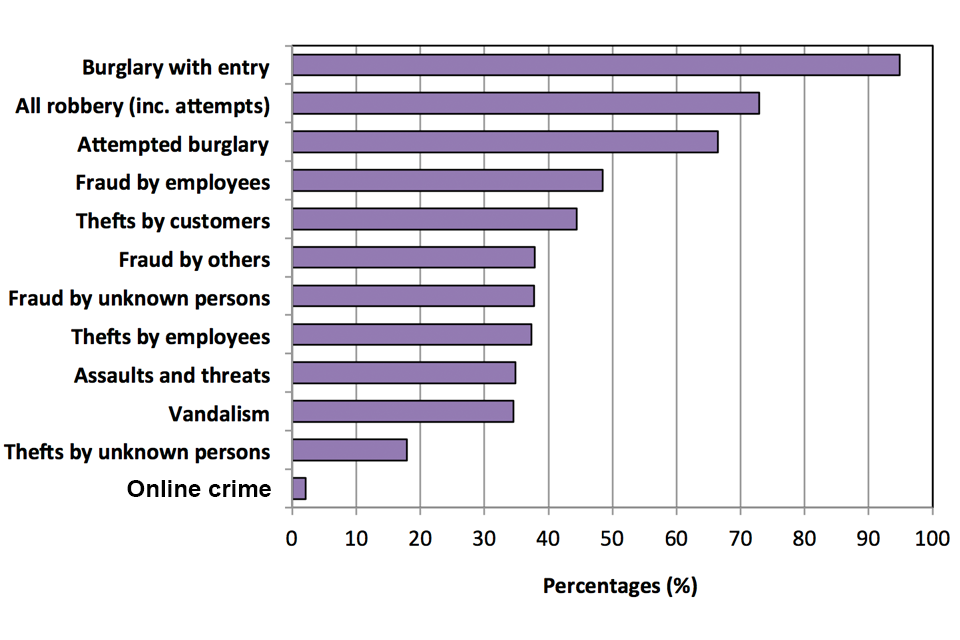

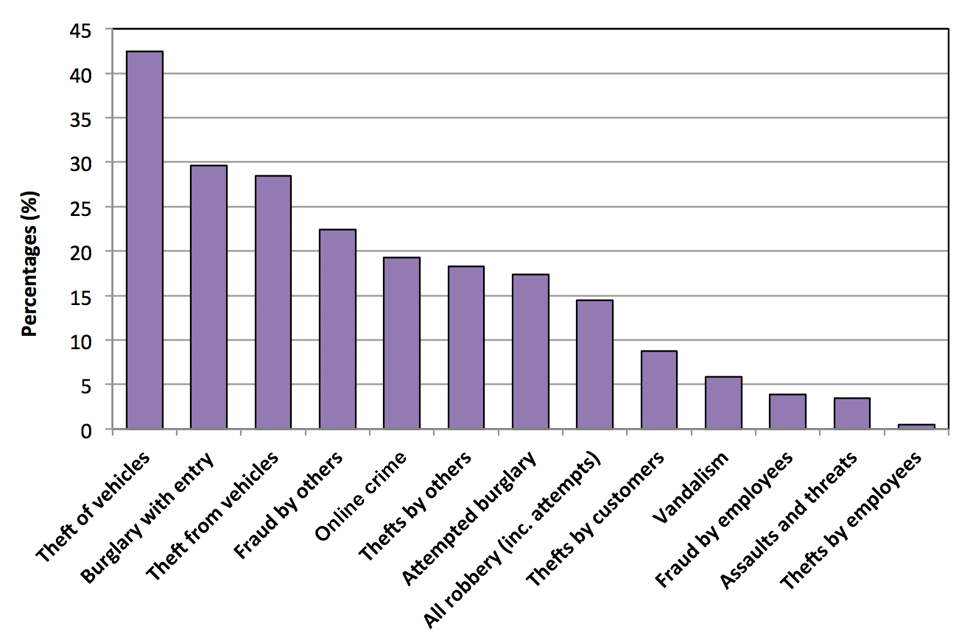

Where sample sizes were large enough to look at reporting rates for the wholesale and retail sector, the CVS showed that reporting rates varied considerably by the type of offence (table 1.8, figure 1.8). Estimates show that incidents of burglary and robbery were well reported, with 95 per cent of incidents of burglary with entry, 73 per cent of incidents of all robbery and 66 per cent of incidents of attempted burglary being reported to police for this sector.

Table 1.8: Proportion of most recent incidents of crime in the wholesale and retail sector reported to police, by crime type, 2012, 2013 and 2014 CVS.

| Percentages | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crime type | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Change (2012 to 14) | Change (2013 to 14) |

| All burglary (inc. attempts) | |||||

| Burglary with entry | 87 | 82 | 95 | +8 | +13 * |

| Attempted burglary | 62 | 66 | 66 | +5 | +1 |

| Vandalism | 46 | 35 | 35 | -11 * | -1 |

| All vehicle-related theft | |||||

| Theft of vehicles | - | - | - | - | - |

| Theft from vehicles | 62 | - | - | - | - |

| All robbery (inc. attempts) | - | - | 73 | - | - |

| Assaults and threats | 29 | 36 | 35 | +6 | -1 |

| All theft | |||||

| Thefts by customers | 41 | 42 | 44 | +3 | +2 |

| Thefts by employees | 28 | 31 | 37 | +10 | +6 |

| Thefts by others | - | - | - | - | - |

| Thefts by unknown persons | 26 | 33 | 18 | -8 | -15 * |

| All fraud | |||||

| Fraud by employees | - | - | 49 | - | - |

| Fraud by others | 42 | 59 | 38 | -4 | -21 * |

| Fraud by unknown persons | - | - | 38 | - | - |

| Online crime | - | - | 2 | - | - |

Table notes

- numbers are rounded to the nearest percentage point; changes between years were calculated before rounding

- results are not shown where the unweighted base was fewer than 50; they are represented by a hyphen (-)

- atatistically significant changes are shown in bold italics with asterisks (*); other changes are not significant

- it is not possible to show percentages for combined crime groups (e.g. all burglary) as the questions on reporting are asked regarding the most recent incident experienced in the last 12 months, which cannot be identified for groups

- fraud offences may have been reported to Action Fraud, the central recording body for fraud offences, not the police

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

The high reporting rates for these crime types are likely to reflect the need for victims to obtain a crime reference number from the police in order to make an insurance claim. Reporting rates were comparatively low for theft by employees (37%), assaults and threats (35%), vandalism (35%) and thefts by unknown persons (18%).

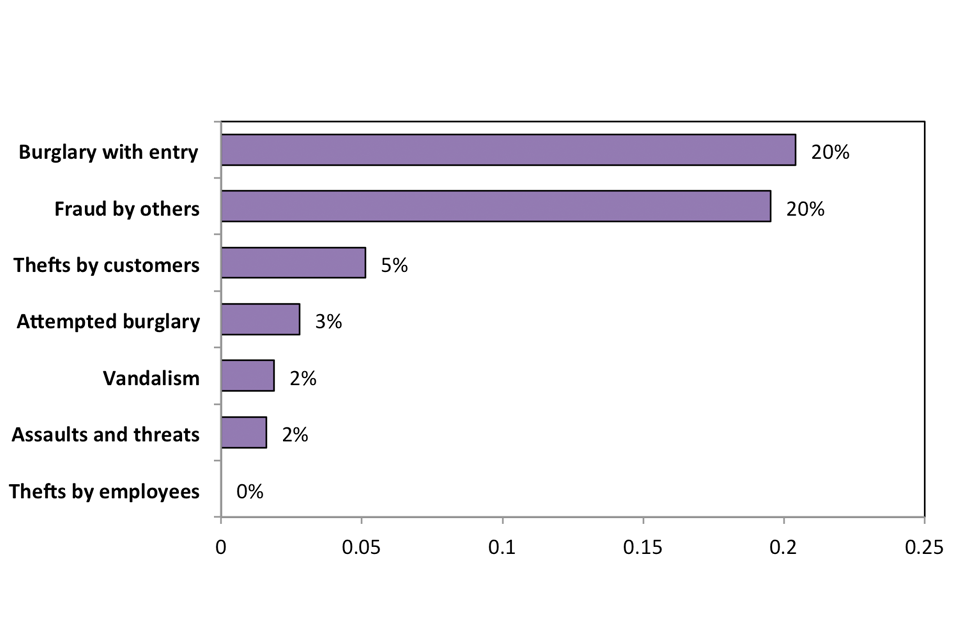

Figure 1.8: Proportion of incidents experienced by premises in the wholesale and retail sector reported to the police (%), for selected crime types, 2014 CVS

.

Chart note

Some categories are not shown due to having an unweighted base of fewer than 50 respondents.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

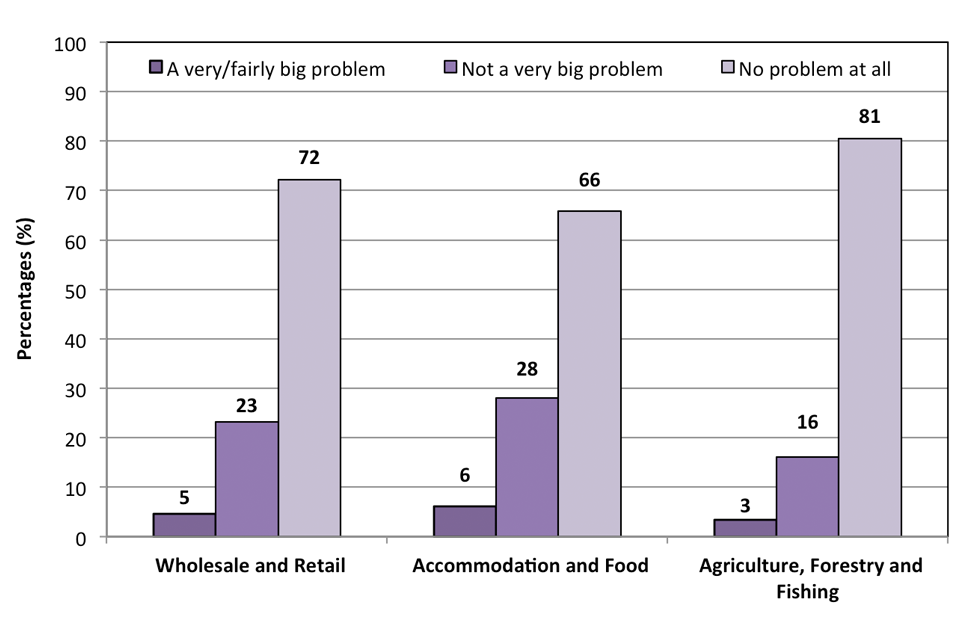

Organised Crime

Organised crime is defined as crime that involves individuals, normally working with others, committing serious crime on a continuing basis. Focusing on the most recent incident of each crime type experienced in the 12 months prior to interview, respondents in the wholesale and retail sector were asked whether they perceived it to have been carried out by “an organised group of criminals”, a “loosely knit group”, or “someone working alone”.

The crime most commonly perceived as organised was burglary with entry, with 35% of respondents saying that they thought the last incident of burglary with entry they experienced was carried out by an organised group of criminals. Attempted burglary was the second most common crime type perceived as organised (27%), followed by fraud by others (22%). Conversely, the crime types least likely to have been perceived as organised crime were thefts by employees (0%), assaults and threats (2%) and vandalism (4%).

Compared with 2013, there has been a small (+4%) but statistically significant increase in the proportion of thefts by customers, which were perceived to have been carried out by an organised group of criminals. The proportion of such incidents remains low (9%) and this is consistent with findings from the Association of Convenience Stores (ACS) which likewise reported that organised crime was attributed to 9 per cent of shop theft.

There have also been larger statistically significant increases in the proportions of burglary (+18%) and attempted burglary (+18%) perceived to be carried out by an organised group compared with 2013. In comparison to 2012, the proportion of attempted burglaries perceived to be organised crime also rose significantly (+19%). However, there is a lot of variation in the estimated numbers of organised crimes over the three years, so these numbers should be interpreted with caution.

Chapter 4 explores the reasons respondents gave for thinking that a crime was carried out by an organised group of criminals. Figures on the proportion of incidents respondents thought were carried out by an organised group of criminals, by industry sector, can be found in Table OC2 in the 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Comparison with 2002

A comparison between the wholesale and retail sector in 2002 and 2012 was carried out for the Crime against businesses: Detailed findings from the 2012 Commercial Victimisation Survey report, published in June 2013. Analysis was based on a subset of the 2012 CVS data in order to make it directly comparable with the 2002 dataset (see the report for more details). The analysis showed there were around 14.5 million fewer crimes against wholesale and retail business premises in 2012 than in 2002 (down from around 21.5 million to around 8 million).

Comparison with other sources

The British Retail Consortium (BRC) Retail Crime Survey 2014 results show that theft by customers made up the majority of crime against retailers (81%) and fraud accounted for the second highest proportion of all retail crimes (17 per cent). This reflects the CVS finding that the most common crime types experienced by the wholesale and retail sector are thefts, although the CVS places assaults and threats as the second most common crime type, followed by fraud.

Although there are some similarities between the CVS and BRC results in terms of the crime types affecting the sector, the trends in crime sometimes differ between the two. This may be due to differences in coverage and methodology between sources. CVS results are based on wholesalers as well as retailers, whereas the BRC survey covers only retailers. In addition, the CVS is sampled at premises level, whereas the BRC samples respondents at enterprise level; differences may therefore be due to incidents not being reported to head offices (for those retailers with head offices), or differences in recording practices at the premises and enterprise level. The time periods of the two surveys also differ, with the CVS being based on calendar years while the BRC survey results are based on financial years.

In addition, victims captured in the CVS are only asked if they reported the most recent incident to the police, not all incidents. Therefore results could be subject to recall error, where respondents recall the most prominent (rather than most recent) incident. This may lead to higher ‘reporting’ figures, as more prominent incidents are more likely to be reported to the police. It is also possible that some CVS victims may say they reported to the police, but actually reported to their internal security, for example. When comparing results of the BRC survey with the CVS, users should bear in mind these differences between the two surveys.

Despite the differences described above, it is useful to compare findings from different sources of data, such as the BRC, CVS, and police recorded crime statistics. According to the BRC survey, customer theft has decreased slightly in the last year, from 631,391 incidents in 2012 to 2013, to 552,069 in 2013 to 2014. This is consistent with the trend shown by the 2014 CVS. However, the BRC also shows a long term increase in customer theft, from just under 3,000 incidents per 100 stores in 2007 to 2008 to around 4,500 in 2013 to 2014.

In the case of burglary rates, the BRC showed a 22 per cent fall between 2012 to 2013 and 2013 to 2014, while the CVS showed a 46 per cent fall in the wholesale and retail sector between 2013 and 2014, which was statistically significant. Both surveys also indicated falls in robbery and employee theft, although in the case of the CVS these falls were not statistically significant. However, there are areas where the two surveys differ. For example, while the BRC survey found that fraud and online crime had increased in 2013 to 2014 compared with the year before, the CVS indicated a fall between 2013 and 2014, albeit not statistically significant.

By contrast, the latest police recorded crime statistics published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show an increase in shoplifting. The number of shoplifting offences recorded by the police rose from 317,047 offences in the year, to December 2013 to 325,504 offences in the year to December 2014, an increase of 3 per cent. However, the increase in the number of offences recorded by the police could be due to an increase in the proportion of shoplifting incidents that come to the attention of police, or changes to police recording practices. This is supported by the fact that the police recorded crime figures are lower than those reported by the CVS and BRC.

The Association of Convenience Stores also present statistics on crime against convenience stores. However, because these only cover a small proportion of premises in the wholesale and retail sector it is hard to directly compare the findings with those from the CVS. The time periods covered also differ. The 2014 survey had 11 respondents representing 3,592 stores, and found that 76 per cent of retailers had experienced some form of theft in their store since 2012.

Further findings

Overall estimates for all of the CVS sectors combined, including for online crime, metal theft and reporting rates are available in Chapter 4.

2. Crime against accommodation and food premises

2.0 Introduction

In the 2014 Commercial Victimisation Survey (CVS), respondents from 1,052 premises in the accommodation and food sector were asked if they had experienced any of a range of crime types in the 12 months prior to interview and, if so, how many incidents of crime had been experienced.

The accommodation and food sector has now been included in the CVS for three years, and so we are able to compare figures over this period. Most of the comparisons presented in this chapter are of 2014 against 2012 findings, as the most prominent changes in crime against this sector occurred over the two-year period. The relatively small sample size of the survey makes detecting changes between adjacent years more difficult. More information will become available in future years as longer trends develop. Comparisons with 2012 and 2013 figures, with results of statistical significance testing and confidence intervals, are presented in the accompanying 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

The 2014 CVS also collected information on areas such as online crime, organised crime, cost of crime, and reporting rates (to the police). This information is presented here, as well as information on repeat victimisation (average number of crimes per victim).

Results for all CVS sectors, including the accommodation and food sector are presented in the accompanying 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Please refer to the introduction to this report for further information about the contents of data tables accompanying the publication.

2.1 Key findings

Crime against the accommodation and food sector fell between 2012 and 2014.

The number of victims of crime (individual premises) in this sector fell from 58,000 victims in 2012 to 45,000 in 2014. The number of incidents has also fallen from 985,000 to 565,000 over the same period, driven largely by falls in theft.

Since 2012, the proportion of premises experiencing crime has decreased across all offence groups.

Overall the proportion of premises that suffer a crime in this sector has fallen, even though for some offences the rate of incidents has increased (for example assaults and threats).

Assaults and threats were the most common crime type against this sector in 2014.

Overall, the 2014 CVS recorded 565,000 crimes against accommodation and food premises, of which 46 per cent (260,000 incidents) were assaults and threats. This is a similar proportion to the 2013 CVS.

Larger premises experienced higher rates of crime than smaller premises.

The rate of crime experienced by premises with 50 or more employees was 19,224 incidents per 1,000 premises compared with 2,146 per 1,000 premises with 1-9 employees, and 7,649 per 1,000 premises with 10-49 employees. The proportion of larger businesses experiencing crime was also much higher.

2.2 Extent of crime against accommodation and food premises

Table 2.1: Experiences of crime in the last 12 months, accommodation & food sector, 2014 CVS

| Crime type | Number of crimes (000s) | Number of crimes per 1,000 premises | Number of victims (000s of premises) | % of premises experiencing | Average number of crimes experienced by each victim (premises) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All burglary (inc. attempts) | 18 | 148 | 12 | 10 | 2 |

| Vandalism | 71 | 588 | 16 | 13 | 4 |

| All vehicle-related theft | 3 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| All robbery (inc. attempts) | 2 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Assaults and threats | 260 | 2,158 | 14 | 12 | 18 |

| All theft | 168 | 1,389 | 16 | 13 | 10 |

| Thefts by customers | 111 | 922 | 9 | 7 | 13 |

| Thefts by employees | 23 | 188 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Thefts by others | 7 | 61 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Thefts by unknown persons | 26 | 218 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| All fraud | 43 | 354 | 10 | 8 | 4 |

| All accommodation and food premises crime | 565 | 4,677 | 45 | 37 | 13 |

Unweighted base: 1,052 premises

Table 2.2: Changes in crime in the accommodation & food sector, 2014 compared with 2012 CVS

| Crime type | Change in number of crimes per 1,000 premises | Change in % of premises experiencing | Change in average number of crimes experienced by each victim (premises) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All burglary (inc. attempts) | -122 * | -5% * | -0.4 * |

| Vandalism | + 19 | -4% * | +1 |

| All vehicle-related theft | + 2 | -0.2% | - |

| All robbery (inc. attempts) | -104 | -1% | - |

| Assaults and threats | +85 | -3% * | +4 |

| All theft | -2,082 * | -3% * | -10 * |

| Thefts by customers | -269 | +1% | -5 |

| Thefts by employees | -1,185 * | -3% * | -18 * |

| Thefts by others | +26 | -0.3% | - |

| Thefts by unknown persons | -655 | -2% * | -8 |

| All fraud | -482 * | -2% | -4 * |

| All accommodation and food premises crime | -2,684 * | -6% * | -4 |

Table notes

- columns related to victims may not sum to the totals shown for all crime; this is because one premises can be a victim of more than one type of crime; other columns may not sum exactly to the total shown due to rounding

- the fall in the incidence rate for employee theft is particularly large; in 2013 there were 233 incidents per 1,000 premises, and in 2014 there were 188 incidents per 1,000 premises, indicating that the 2012 estimate was particularly large

- statistically significant changes are indicated with asterisks (*); other changes are not significant

- a hyphen (-) indicates that a figure is not shown because its unweighted base is fewer than 50 respondents

Source

Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables and 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

There were 565,000 crimes against accommodation and food premises in the year prior to interview, and 37 per cent of premises in the sector had experienced at least one incident of crime (of any type) within the last 12 months. Each victim in the accommodation and food sector had experienced an average of 13 incidents in the previous 12 months. These figures are presented in table 2.1.

Assaults and threats were the most common crime type, making up 46 per cent of all incidents against this sector (260,000 incidents). Twelve per cent of premises in this sector had experienced at least one such incident in the last year. Victims of assaults and threats experienced a relatively high level of repeat victimisation compared with victims of other crime types, with an average of 18 incidents per premises in the 12 months prior to interview. Differences are also apparent for other crime types, for example vandalism and theft have very similar prevalence levels, but theft has a much higher incidence rate, which suggests greater repeat victimisation.

The total estimated number of crimes against the accommodation and food sector fell from 985,000 in 2012 to 565,000 in 2014. The main driver of this was a fall in the number of incidents of theft, which fell from 465,000 in 2012 to 168,000 in 2014 (accounting for 71% of the overall fall). There were large falls in the number of thefts by employees (from 184,000 to 23,000) and thefts by unknown persons (from 117,000 to 26,000). The direction of change across each crime type is summarised in table 2.2, see the 2014 CVS Comparison Tables for a more detailed breakdown.

Number of incidents per 1,000 premises

The rate of crime against the accommodation and food sector fell by over a third, from 7,361 incidents per 1,000 premises to 4,677 per 1,000 premises between 2012 and 2014. In 2012, thefts were the most common crime type experienced by the accommodation and food sector (3,471 incidents per 1,000 premises). However, as in 2013, assaults and threats are now the most common crime type experienced by the sector (2,158 incidents per 1,000 premises in 2014). Changes over time are summarised in Figure 2.1 below.

Figure 2.1: Incidents of crime per 1,000 premises experienced by the accommodation and food sector in the last 12 months, with associated 95% confidence intervals, 2012, 2013 and 2014.

.

Chart notes

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. While non-overlapping confidence intervals usually indicate a statistically significant difference, overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance.

Source

Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

Proportions of premises that experienced a crime

After remaining steady between 2012 and 2013, the level of victimisation in the accommodation and food sector fell by 6 percentage points in 2014.

The change in the prevalence rate for specific crime types are shown in figure 2.2. Between 2013 and 2014 there has been a significant decline in the proportion of premises suffering assaults and threats while incidence rates have stayed fairly flat. This suggests that those that have suffered assaults and threats have been repeat victims in a number of cases. During this period the number of incidents per victim has increased from 13 to 18, but this was not statistically significant.

Figure 2.2: Proportion of premises experiencing incidents of crime in the accommodation and food sector in the last 12 months, with associated confidence intervals, 2012, 2013, and 2014.

.

Chart notes

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. While non-overlapping confidence intervals usually indicate a statistically significant difference, overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance.

Source

Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

Incidence and prevalence rates by business size

As previously shown by the 2012 and 2013 CVS, incidence rates of crime (i.e. number of incidents per 1,000 premises) are noticeably higher for premises with more employees. During 2014, small, medium and large businesses experienced markedly different incidence and prevalence rates of crime. Premises with 50+ employees experienced approximately 8 times more incidents per 1,000 premises compared with the smallest premises (1 to 9 employees) (Table 2.3).

This difference in rate is largely driven by the main three crime types in this sector: (i) assaults and threats (ii) theft and (iii) fraud (Figure 2.3). Table 2.3 shows that the prevalence rate is higher for every crime type for premises with 50 or more employees compared with premises with 1-9 or 10-49 employees.

Table 2.3: Incidents of crime per 1,000 premises and proportion of premises experiencing at least 1 incident of crime, by premises size, accommodation and food sector, 2014 CVS.

| 1 to 9 employees | 10 to 49 employees | 50+ employees | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| incidence (per 1,000) | prevalence (%) | incidence (per 1,000) | prevalence (%) | incidence (per 1,000) | prevalence (%) | |

| All burglary (inc. attempts) | 139 | 9 | 157 | 11 | 230 | 14 |

| Vandalism | 464 | 13 | 787 | 13 | 1,015 | 18 |

| All vehicle-related theft | 9 | 1 | 38 | 1 | 119 | 2 |

| All robbery (inc. attempts) | 10 | 0 | 34 | 2 | 38 | 2 |

| Assaults and threats | 805 | 8 | 4,018 | 18 | 10,012 | 28 |

| All theft | 750 | 11 | 2,299 | 17 | 4,776 | 30 |

| All fraud | 237 | 6 | 316 | 10 | 3,033 | 24 |

| All accommodation and food premises crime | 2,416 | 32 | 7,649 | 45 | 19,224 | 58 |

Unweighted base: 1,052 premises

Source

Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Figure 2.3: Incidents of crime per 1,000 premises experienced by the accommodation and food sector in the last 12 months, by number of employees at premises, 2014 CVS

.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

Average number of incidents of crime per victim (premises)

Overall, each victim of crime in the accommodation and food sector experienced an average of 13 incidents in the last year. The highest average numbers of incidents per victim were for assaults and threats, with each victim experiencing an average of 18 incidents of this crime type in the last year. Theft by customers has the next highest rate of repeat victimisation, at 13 incidents per victim.

The level of repeat victimisation for theft by employees have decreased significantly, driving an overall significant decrease in the level of repeat victimisation for theft overall. There has also been a significant decrease in repeat victimisation for fraud offences.

2.3 Other results from the survey

This section includes findings about online crime, reporting rates (to the police) and organised crime in the accommodation and food sector.

Online crime

Online crime covers a range of crime types carried out over computer networks. Respondents from this sector, who used computers at their premises, were asked about their experience of various types of online crime. See the Technical Annex for the types covered in the survey and for further details of online crime. It is important to bear in mind that respondents were only asked about online crimes affecting the premises. Many online crimes may affect only head offices and so will not be picked up by the survey.

Half of the respondents from the accommodation and food sector were asked whether computers were used at the premises. Those who used computers were then asked about their business’s experience of online crime. In the accommodation and food sector 68 per cent of businesses said they used computers, compared with 84 per cent across all the six sectors for which data are available. Computer use is probably lower in this sector because of the types of businesses it encompasses are far less likely to have computers.

Table 2.5: Experiences of online crime in the last 12 months, accommodation & food sector, 2014 CVS

| Crime type | Number of crimes (000s) | Number crimes per 1,000 premises | Number of victims (000s of premises) | % of premises experiencing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hacking | 4 | 32 | 2 | 2 |

| Phishing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Theft of money (online) | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Theft of information (online) | 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| Website vandalism | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Computer virus | 12 | 103 | 6 | 5 |

| All online crime | 19 | 155 | 8 | 7 |

Unweighted base: 488 premises.

Table notes

- columns related to victims may not sum to the totals shown for all online crime; this is because one premises can be a victim of more than one type of crime; other columns may not sum exactly to the total shown due to rounding

- since computers are used at a high proportion of premises, incidence and prevalence rates are reported relative to the total number of business premises in the sector, not only those where computers are used

- incidents of online crime are not included in the overall count of CVS crime as these questions are only asked of half the sample and there is a risk of double-counting with other crime types, such as theft or fraud

- although described here as crimes, it is worth noting that not all of these incidents would be recorded as a crime by the police; whether receiving a phishing email or being infected by virus is counted under police recorded crime depends on whether the incident was targeted at a specific victim, or any financial loss was incurred, as per the Home Office Counting Rules.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

The 2014 CVS estimates there were 19,000 incidents of online crime against businesses in the accommodation and food sector in the 12 months prior to interview, an increase compared with 2013 (13,000 incidents), and compared with 2012 (16,000 incidents). Neither change is statistically significant.

The most commonly experienced online crimes in each of the last three years were computer viruses. In 2014 there were 12,000 incidents in the year prior to interview, making up 66 per cent of all incidents of online crime against this sector. In 2013 computer viruses made up 64 per cent of all online crimes in this sector, and in 2012 this proportion was 50 per cent.

Reporting rates

The CVS asked those respondents who had experienced crime in the past year whether the police came to know about the most recent incident of each crime type experienced.

Where sample sizes were large enough to look at reporting rates for the accommodation and food sector, the CVS showed that reporting rates varied considerably by the type of offence (Figure 2.4). Estimates show that incidents of burglary with entry were well reported, with 92 per cent of incidents of incidents being reported to police for this sector.

Reporting rates were low for thefts by customers, where only 23 per cent were reported to the police.

There has been a significant fall in the number of incidents of thefts by customers reported to the police between 2012 and 2014, in contrast to the wholesale and retail sector where the reporting rate has remained steady.

The figures suggest that the reporting rate is highest for crimes where the largest financial losses were incurred, and a crime reference number was needed for insurance purposes. For example, the 2013 CVS found burglary with entry to be one of the costliest crimes in terms of the median value of goods stolen per incident, and figure 2.4 shows that this crime type has the highest reporting rate.

Figure 2.4: Proportion of incidents experienced by premises in the accommodation and food sector reported to the police (%), for selected crime types, 2014 CVS.

.

Chart notes

- results are not shown where the unweighted base was fewer than 50

- it is not possible to show percentages for combined crime groups (e.g. all burglary) as the questions on reporting are asked regarding the most recent incident experienced in the last 12 months, which cannot be identified for groups

- fraud offences may have been reported to Action Fraud, the central recording body for all fraud offences, not the police

Source

Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Organised Crime

Organised crime is defined as a crime that involves individuals, normally working with others, committing serious crime on a continuing basis. Focusing on the most recent incident of each crime type experienced in the 12 months prior to interview, respondents in the accommodation and food sector were asked whether they perceived it to have been carried out by “an organised group of criminals”, a “loosely knit group”, or “someone working alone”.

In 2014 the crimes most commonly perceived as organised were burglary with entry, and fraud by others, with 20% of respondents saying that they thought the last incidents they had experienced of burglary with entry, or fraud by others, had been carried out by an organised group of criminals. The most common crime type in this sector (assaults and threats) was seldom (2%) perceived to be organised.

Chapter 4 explores the reasons respondents gave for thinking that a crime was carried out by an organised group of criminals. Figures on the proportion of incidents respondents thought were carried out by an organised group of criminals, by industry sector, can be found in Table OC2 in the 2014 CVS Headline Tables. Figure 2.5 below summarises the proportion of each crime type thought to be carried out by an organised group for the accommodation and food sector. Not all crime types are shown, as the number of respondents did not allow for robust estimates in all cases.

Figure 2.5: The proportion of victims for each crime type who thought the crime they experienced involved an organised group of criminals.

.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Further findings

Overall estimates for all of the CVS sectors combined, including for online crime, organised crime, and reporting rates are available in Chapter 4.

3. Crime against agriculture, forestry and fishing premises

3.0 Introduction

Respondents to the 2014 Commercial Victimisation Survey (CVS) from premises in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector were asked if the business at their current premises had experienced any of a range of crime types in the 12 months prior to interview and, if so, how many incidents of crime had been experienced. In addition, the 2014 CVS also collected information on other crime types, such as livestock and chemical theft, organised crime and reporting rates. These, alongside comparisons to 2013 figures, are presented here and in the 2014 CVS Comparison Tables. This sector was not included in the 2012 survey; premises from the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector were covered by the Commercial Victimisation Survey (CVS) for the first time in 2013.

The estimates presented in this chapter are based on interviews with respondents at 1,019 agriculture, forestry and fishing sector premises. Data are weighted to ensure that the sample is representative of businesses in this sector in England and Wales as a whole.

The majority of premises interviewed from the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector describe farming as the main activity at the premises. Of the 843 farming premises, around half farmed animals, a quarter were crop farmers and a further quarter farmed both animals and crops. This is very similar to the sample from this sector interviewed for the 2013 CVS.

Results for all CVS sectors, including the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector are presented in the 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Please refer to the introduction to this report for further information about the contents of data tables accompanying the publication.

3.1 Key findings

Of all sectors surveyed by the CVS, the agriculture sector experienced the least crime.

There were around 95,000 crimes affecting around 26 per cent of agriculture, forestry and fishing premises in 2014. Both figures have fallen slightly compared with 2013 (but this is not statistically significant), and remain the lowest incidence and prevalence rates among all six sectors surveyed in 2012-2014.

The number of burglaries per 1,000 premises in the agriculture sector fell by over a third.

Compared with 2013, the number of incidents of burglary with entry per 1,000 premises in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector fell from 206 to 132.

Theft and vandalism were the most common crime types experienced in this sector.

Theft made up 33 per cent of incidents, while vandalism made up around a quarter (24%) of all incidents against agriculture, forestry and fishing premises in 2014.

3.2 Extent of crime against agriculture, forestry and fishing premises

Table 3.1: Experiences of crime in the last 12 months, agriculture, forestry & fishing sector, 2014 CVS

| Crime type | Number of crimes (000s) | Number of crimes per 1,000 premises | Number of victims (000s of premises) | % of premises experiencing | Average number of crimes experienced by each victim (premises) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All burglary (inc. attempts) | 19 | 232 | 9 | 11 | 2 |

| Vandalism | 23 | 269 | 7 | 8 | 3 |

| All vehicle-related theft | 4 | 48 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| All robbery (inc. attempts) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Assaults and threats | 10 | 123 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| All theft | 31 | 375 | 7 | 8 | 5 |

| All fraud | 7 | 80 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| All agriculture, forestry and fishing premises crime | 95 | 1,131 | 22 | 26 | 4 |

Unweighted base: 1,019 premises

Table 3.2: Changes in crime in the agriculture, forestry & fishing sector, 2014 compared with 2013 CVS

| Crime type | Change in number of crimes per 1,000 premises | Change in % of premises experiencing | Change in average number of crimes experienced by each victim (premises) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All burglary (inc. attempts) | -55 | -4 * | +0.2 |

| Vandalism | -174 | -2 | -1 |

| All vehicle-related theft | -20 | -1 | -0.09 |

| All robbery (inc. attempts) | -6 | -0.1 | - |

| Assaults and threats | -40 | -1 | - |

| All theft | -13 | -1 | 1 |

| All fraud | -35 | -1 | - |

| All agriculture, forestry and fishing premises crime | -345 | -4 | -1 |

Table notes

- columns related to victims may not sum to the totals shown for all crime; this is because one premises can be a victim of more than one type of crime; other columns may not sum exactly to the total shown due to rounding

- statistically significant changes are indicated with asterisks (*); other changes are not significant

- a hyphen (-) indicates that a figure is not shown because its unweighted base is fewer than 50 respondents

Source

Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables and 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

Agriculture, forestry and fishing premises experienced 95,000 crimes in the year prior to interview. This fall compared with 2013 (when the CVS estimated 133,000 crimes) is not statistically significant.

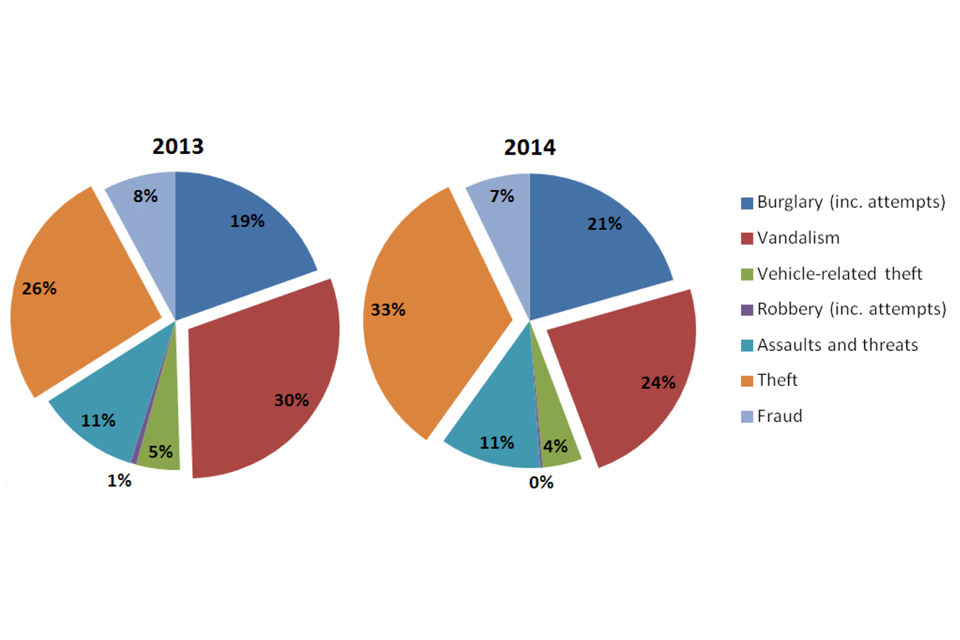

Compared with 2013, the proportions of incidents attributed to each crime type have remained similar, with prominent differences only for the two most common crime types for this sector: (i) theft and (ii) vandalism.

Figure 3.1: Proportions of incidents of crime attributed to each crime type, agriculture, forestry and fishing sector, 2013 and 2014 CVS

.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Number of incidents per 1,000 premises

As discussed in chapter 4, the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector experienced relatively low rates of crime compared with the other sectors surveyed in 2014. Table 3.1 shows that the highest rates of crime against this sector were for thefts (375 incidents per 1,000 premises), followed by vandalism (269 incidents per 1,000 premises), burglary (232 incidents per 1,000 premises) and assaults and threats (123 incidents per 1,000 premises).

Figure 3.2: Incidents of crime per 1,000 premises experienced by agriculture, forestry and fishing premises in the last 12 months, with 95% confidence intervals, 2013 and 2014 CVS

.

Chart notes

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. While non-overlapping confidence intervals usually indicate a statistically significant difference, overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance.

Source

Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.

Compared with 2013, within the main crime types there has been a statistically significant fall in the incidence rate of burglary with entry, down from 206 to 132 incidents per 1,000 premises. There was also a notable fall in the number of incidents of vandalism (down by 174, from 443 in 2013), but this is not statistically significant. Other changes in incidence rates can be found in the 2014 CVS Comparison Tables and are illustrated by Figure 3.2.

As shown in Figure 3.3 below, the highest rates of crime at agriculture, forestry and fishing premises were among those with 10-49 employees, which are similar to those for premises with 50 or more employees. This differs from the other sectors, where larger businesses appear to experience higher crime rates.

Figure 3.3: Number of incidents of crime per 1,000 premises experienced by the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector in the last 12 months, by number of employees at premises, 2014 CVS

.

Source: Home Office, 2014 CVS Headline Tables.

Proportions of premises that experienced a crime

Just over a quarter (26%) of agriculture, forestry and fishing premises experienced at least one incident of crime in the 12 months prior to interview. This is the lowest prevalence rate among the six sectors surveyed in 2012, 2013 and 2014. The most prevalent crime type in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector in 2014 was burglary, which 11 per cent of premises experienced.

The 2013 CVS found that, in contrast to other sectors, where the majority of premises have alarms installed, only a third (32%) of agriculture, forestry and fishing premises had one. However, the 2013 survey results also indicated that the presence of a burglar alarm does not fully offset the risk of victimisation in high-risk and accessible locations. This shows some similarities with a finding by Tilley et al (2015), whereby alarms were actually associated with increased risk of burglary in households.

Two per cent of premises experienced theft of a vehicle (with no change compared with 2013). According to findings from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW), this proportion is higher than the proportion of vehicle theft incidents experienced by households. The CSEW estimated that 0.2 per cent of households experienced theft of a vehicle in the year to December 2014. Figures for overall vehicle-related theft, which includes both theft of a vehicle and theft from vehicles, were similar for businesses in the agriculture sector and vehicle-owning households (both around 3%). This may suggest that in vehicle-related theft against this sector, the vehicle itself is more frequently a target, most likely due to higher value compared with household vehicles. The NFU Rural Crime Survey 2014 revealed that the cost of rural theft has been driven up by thefts of high-value tractors worth up to £80,000, while thieves are also targeting lower value tractors not fitted with high-tech systems. Conversely, in household vehicles, the contents may be more frequently targeted.

Compared with 2013 there were small (but statistically significant) falls in the proportions of premises that experienced burglary (-4%) and thefts by employees (-1%). There were no increases in prevalence rates for any crime types. The changes are shown below in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4: Proportion of agriculture, forestry and fishing premises that experienced crime in the last 12 months, by type, with 95% confidence intervals, 2013 and 2014 CVS

.

Chart notes

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. While non-overlapping confidence intervals usually indicate a statistically significant difference, overlapping confidence intervals do not always indicate a lack of statistical significance.

Source

Home Office, 2014 CVS Comparison Tables.