Guide to Family Court Statistics

Published 25 March 2021

File named as: Guide to Family Court Statistics

1. Introduction

Family Court Statistics in England and Wales are published every quarter, presenting the key statistics on activity in the family court system. This document aims to provide a comprehensive guide to the family court system, focusing on concepts and definitions published in Ministry of Justice statistics. It also covers statistical publication strategy, revisions, data sources, data quality, and dissemination. There is also a separate Quality Statement released alongside this guide.

The key areas covered in this guide are:

- A high-level background to the family court system, focusing on the topics featured in the Family Court Statistics Quarterly (FCSQ) bulletin.

- Information on the frequency and timings of the bulletin and its revisions policy.

- Details of the data sources and any associated data quality issues.

- Major legislation coming into effect in the period covered by the bulletin.

- A glossary of the main terms used within the publications.

- A list of relevant internet sites on the Family Court system.

2. Background to the Family Court statistics

Family law is the area of law that deals with:

- Public law – local authority intervention to protect children;

- Private law – parental disputes concerning the upbringing of children;

- Matrimonial cases – divorces, annulments and separations;

- Financial Remedy (formerly known as ‘ancillary relief’) – financial provisions after divorce or relationship breakdown;

- Domestic violence remedy orders;

- Forced marriage protection orders;

- Female genital mutilation protection orders;

- Adoption;

- The Mental Capacity Act; and

- Probate.

The Single Family court (also known as ‘the Family Court’) was implemented on 22 April 2014. Proceedings are issued by the Family Court and are allocated to a level of judge according to their type and complexity. The Single Family court aims to enable magistrates, legal advisers and the judiciary to work more closely together.

Previously, family cases were dealt with at Family Proceedings Courts (which were part of magistrates’ courts), at county courts or in the Family Division of the High Court. These cases are now dealt within the Single Family Court and the High Court and most cases affecting children are dealt with under the Children Act 1989.

The Designated Family Judge (DFJ) now has an increased role in leading the Family Court and managing its workload in distinct areas across England and Wales. These distinct areas are still called DFJ areas. Each DFJ area has a Designated Family Centre which is the principal family court location for each DFJ area. This is the location where all family applications from that DFJ area are sent to for initial consideration.

Family cases still need HM Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS) staff to administer them through the Family Court. What may have changed is how family work is received, distributed and listed within the DFJ areas. For example, in some areas more family work may be heard at the Designated Family Centre, with allocation and listing being managed from that location, with some other work taking place elsewhere.

3. Public Law

Public law cases are those brought by local authorities or an authorised person (currently only the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children) to protect the child and ensure they get the care they need. In these proceedings, the child is automatically a party and is represented by a Children’s Guardian appointed by the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass). The Children’s Guardian is an independent person who is there to promote the child’s welfare and ensure that the arrangements made for the child are in his or her best interests.

A range of different orders can be applied for. The main types of order are a care or supervision order which determines whether the child should be looked after or supervised by the local authority, and an emergency protection order which allows an individual or local authority to take a child away from a place where they are in immediate danger to a place of safety. The majority (two thirds) of Public law applications are for care orders.

The Public Law Outline flowchart provides more information about the main court processes for Children Act Public Law cases.

Following the publicity surrounding Baby P case[footnote 1], the number of children involved in public law applications made by local authorities jumped from around 20,000 in 2008 to almost 26,000 in 2009, and subsequently to 29,500 in 2011 (Table 2). Figures remained steady until late 2015, after which there has been a steady increase, such that there are now nearly 36,000 children involved in public law applications. The MoJ and HMCTS are continuing to look into the reasons behind the recent increases in public law applications.

Cafcass also publishes data on the number of care applications.

Case level care order figures are currently not produced by the MoJ and so comparisons between the two datasets cannot be made at this time.

3.1 Timeliness of Public Law Care and Supervision applications

In the interests of the child, courts try to minimise the length of time it takes for a case to be resolved. However, many factors can affect how long the case takes, such as the type of order applied for, the number of parties involved and how complex the child’s situation is. In general, there is a wide spread of case durations with many straight-forward cases being completed fairly quickly, more complicated cases taking longer and a few very complex ones taking a long time.

The care and supervision timeliness measure presented in this bulletin considers cases that began with a care or supervision application and measures the time from the application until the first of seven disposal types for each individual child. The seven valid disposal types for the purposes of this measure are a care order, a supervision order, a residence order, a special guardianship order, the application withdrawn, an order refused or an order of no order.

The bulletin presents the average, or ‘mean’, case duration, which can be quite heavily influenced by a few very long durations. We therefore also present the median timeliness which is the length of time within which a definitive disposal was reached for half of all children involved which is less affected by cases with very long durations.

4. Private Law

Private law cases are court cases between two or more private individuals who are trying to resolve a dispute. This is generally where parents have split up and there is a disagreement about who the children should live with and have contact or otherwise spend time with. A range of different types of court order can be applied for, including “Section 8” orders (referring to the relevant section of the Children Act 1989), parental responsibility, financial applications and special guardianship orders. The vast majority of private law applications are for Section 8 orders, which include a child arrangements order determining who the child should live with and when and who a child should have contact with or spend time with.

The Private Law Outline flowchart provides more information about the main court processes for Children Act Public Law cases.

Cafcass also publishes (England only) data on the number of private law cases started.

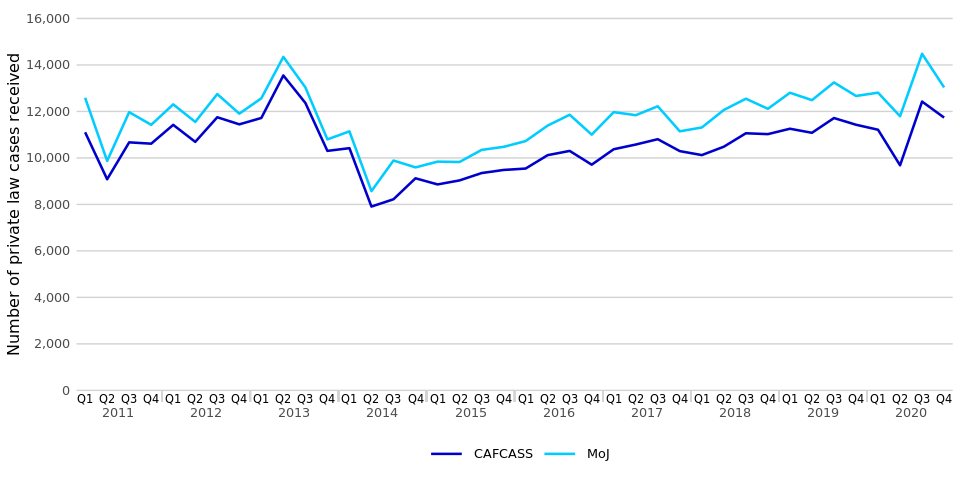

Figure 1 compares both Cafcass and MoJ figures and shows that the trends are similar (for the last three years, MoJ figures have been, on average, 11% higher).

The difference between MoJ and Cafcass figures is mainly due to Cafcass only receiving section 8 cases[footnote 2] from the courts. Other differences between the datasets include the following:

- Section 8 cases where all of the issues are dealt with on the day (called ‘urgent without notice’ applications) should not be sent to Cafcass

- Section 8 cases which are not listed within the Private Law Programme (PLP) and do not have a first hearing dispute resolution appointment (FHDRA) should also not be sent to Cafcass

- Certain non-section 8 cases can be sent to Cafcass if the subject child is a party to ongoing proceedings (and a Cafcass officer has been appointed as the children’s guardian) or the court is directed to do so by a judge or legal advisor

This accounts for the discrepancy between the two datasets which cannot be accurately matched as it is impossible to identify the various situations described above from administrative data sources (particularly the ‘urgent without notice’ applications).

Figure 1: Comparison of the number of private law cases received, as recorded by Cafcass and MoJ (England only), January to March 2011 to October to December 2020

4.1 Timeliness of Private Law Cases

The private law timeliness measure presented in the quarterly bulletin considers cases that began with a private law application and measures the time from case start date until a final order has been issued in the family court.

As with public law, it presents the average, or ‘mean’, case durations, which can be quite heavily influenced by a few long durations, and therefore the median timeliness which is the length of time within which a definitive disposal was reached for half of all the cases is also presented.

4.2 Disposal of public and private law applications

There are four ways in which an application can be disposed of:

- withdrawn applications – applications can only be withdrawn by order of the court.

- order refused – in public law proceedings, an order is refused if the grounds are not proved and the court has dismissed the application. In private law proceedings, the court may refuse to make an order or make an order of no order.

- order of no order – this is made if the court has applied the principle of non-intervention under section 1(5) of the Act. This means that the court shall not make an order unless it would be better for the child to make an order.

- full order made – the type of order made may not be the same as the type of application that was originally applied for. An order is made in favour of one of the parties (Local Authority, parent or other guardian) however this aspect of the case outcome is not recorded on the central case management system (FamilyMan).

If a child arrangement order is breached, a party may apply to the court for an enforcement order to be made. Since December 2008, contact orders (and subsequently child arrangement orders) routinely contain a warning notice stating the consequences if a party fails to keep to the requirements of the order. For earlier orders, the party seeking enforcement must first apply to the court to have a warning notice attached to the order, and the relevant party informed that a notice has been attached. The enforcement order generally requires the person who has breached the order to undertake unpaid work, although if a party has suffered financial loss as a result of the breach they may apply for financial compensation. If other types of order are breached, it is possible for a party to apply for committal, so the breach is dealt with as contempt of court; however, this is very rare.

4.3 Children involved in applications/orders made – Table 2

When a Children’s Act case is put forward, there are several parts to consider – in particular, the number of applications, the number of children involved, the number of different order types being applied for.

The table below demonstrates an example of one case, where one application is being made for 2 children (X and Z). The application is for both children to have a Section 8 Contact order and Resident order. This shows:

- one case

- one application

- two children

- both children being subject to two orders

| Case | Event | Order type | Child ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Application | Child Arrangement Order (Contact) | X |

| A | Application | Child Arrangement Order (Contact) | Z |

| A | Application | Child Arrangement Order (Residence) | X |

| A | Application | Child Arrangement Order (Residence) | Z |

As such, the ‘Number of children’ label in Table 2 counts the total number of applications/orders/disposals scaled up by the number of children involved.

4.4 Mediation

Mediation can be particularly beneficial where there will be a continuing relationship following dispute resolution – such as in family cases. Family mediation can help reduce hostility and improve chances of long-term co-operation between parents and couples, for example in agreeing arrangements for their children and financial matters.

Before applying to the Family Court, people will need to prove they’ve considered mediation first. They can do this:

- by showing they are exempt from having to consider mediation, for example, if domestic violence is involved; or

- by proving to the judge that they have been to a ‘mediation information and assessment meeting’ (MIAM) with a family mediator but that mediation is not suitable for them.

This was enacted in the Children & Families Act 2014.

The Legal Aid Agency publishes figures on the number of publicly funded mediations: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/legal-aid-statistics

5. Legal representation

Legal representation status as published within family court statistics reflects whether details of an applicant’s/respondent’s legal representative has been recorded or left blank within FamilyMan, the family court case management system. A blank field is assumed to indicate that no legal representative has been used.

Table 10 suggests that for almost half of the divorces not involving financial remedies disposed, neither party had legal representation. However, further analysis shows that these were uncontested cases and almost all of them did not have a single hearing. Therefore, parties recorded as without legal representation are not necessarily self-representing litigants in person.

To provide a better proxy for litigants in person, a new table was produced which gives the number of parties in cases with at least one hearing, by their legal representation status (Table 11).

There was a revision to the methodology used to produce Tables 10 and 11[footnote 3] – specifically to account for the issue in public law cases where applicants would generally be public bodies (mostly local authorities) with access to their own legal resources, but who would previously have been shown as an ‘unrepresented’ party. This has now been amended such that they are now shown as represented parties in the above tables, and this has changed the percentage of applicants with legal representation in public law cases with at least one hearing from around 20% to 99%. The overall trends seen in the mean time to disposal of public law cases by representation type however (Table 10) have not changed.

Please note that the majority of the work done in the Court and Tribunal Service Centre in divorce (see page 14) are online applications from unrepresented parties.

5.1 Legal representation and its relationship with timeliness

Different types of cases tend to take different lengths of time to complete – in general public law cases for children take longer than private law cases and divorce cases tend to be quite lengthy due to set time limits, whereas domestic violence cases are usually completed in a fairly short time due to their nature. Another factor that may influence how long a case takes is whether one or both parties had a legal representative or alternatively represented themselves. This may also be affected by whether the parties consent to the application or are contesting it which in turn may reflect the complexity of the case.

5.2 Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) Act 2012

This created the Legal Aid Agency, an executive agency of the Ministry of Justice, on the 1st April 2013, following the abolition of the Legal Services Commission. The implementation of the Act also made changes to the scope and eligibility of legal aid, removing some types of case from the scope of legal aid funding, and only allowing other cases to qualify if they meet certain criteria. Funding is no longer available for private family law, such as divorce and disputes over arrangements for children. Family law cases involving domestic violence, forced marriage or child abduction will continue to receive funding.

Full details of the LASPO Act.

The removal of legal aid for many private law cases resulted in a change in the pattern of legal representation, and Figure 4 of the FCSQ bulletin shows how this changed over time. Around the time that the LASPO reforms were implemented, there was a marked increase in the number and proportion of cases where neither party were represented, with an equivalent drop in the proportion of cases where both parties were represented. In 2018, neither the applicant nor respondent had legal representation in 37% of private law disposals, an increase of 18 percentage points from 2013. Correspondingly, the proportion of disposals where both parties had legal representation dropped by 13 percentage points over the same five-year period.

The Legal Aid Agency (LAA - formerly the Legal Services Commission) collects statistics on those applying for legal aid, and figures on the number of applications received and certificates granted by various Family categories have been published in their annual and quarterly statistical reports, which can be found here: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/legal-aid-statistics

6. Matrimonial cases

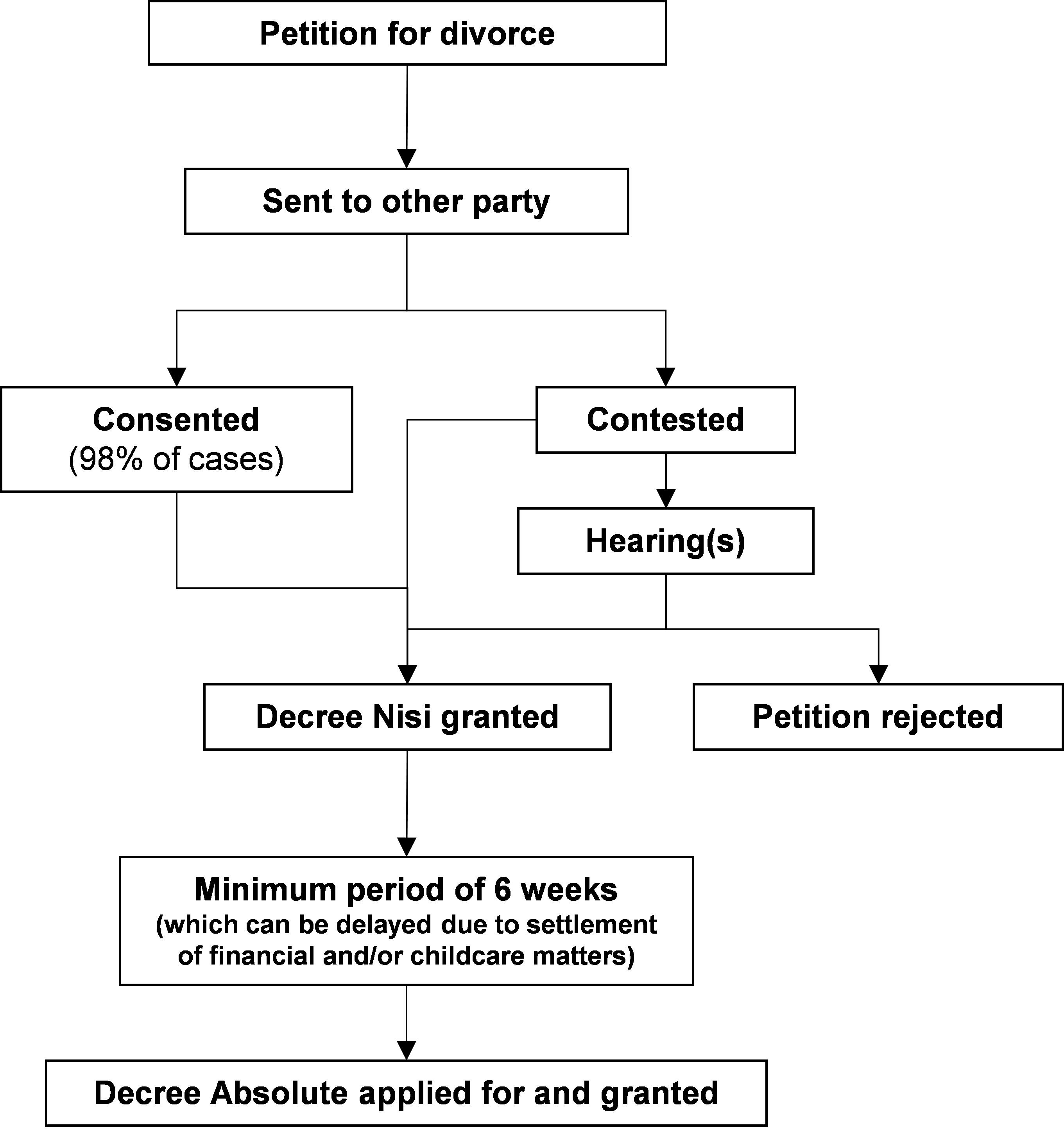

There are two ways to legally end a marriage or a civil partnership. An individual can apply for a divorce which will give them a decree absolute, ending a valid marriage or civil partnership – this occurs in the vast majority of cases. Alternatively, an individual can apply for a decree of nullity, which declares that the marriage or civil partnership itself is void, specifically no valid marriage or civil partnership ever existed; or voidable, specifically the marriage or civil partnership was valid unless annulled. No application can be made for divorce within the first year of a marriage or a civil partnership. An alternative to divorce is a decree of judicial separation or a decree of separation of civil partners, but this does not allow them to remarry or enter into a civil partnership. Figure 2 shows the main court processes for divorce or dissolution cases.

The Office of National Statistics also publishes statistics on the number of divorces occurring each year in England and Wales.

Figure 2: The main court processes for divorce cases

Eleven centralised divorce centres were introduced during 2014 and 2015 in England and Wales, with the vast majority of uncontested decree nisi applications being considered by Legal Advisers (rather than district judges) at those centres. As a result of the introduction of centralised divorce centres, an accompanying csv file with a breakdown of divorce petitions by county and urban area based on petitioner postcode data is provided annually. This is to provide a more representative breakdown of the location of divorce petition applications.

Some divorce centres have since closed, with further closures planned in coming months. A greater proportion of divorce cases are moving to the digital system (see below) and being handled by the Courts and Tribunal Service Centres (CTSCs). Further details on court closures can be provided upon request.

Please note, following the Children and Families Act 2014, couples divorcing are no longer required to provide information on children as part of the divorce process. We have therefore removed this information from the accompanying relevant csv file to avoid misleading conclusions being made.

6.1 Digital system

Following a testing phase, those citizens seeking to apply for divorce could do so via an online service which was rolled out across England and Wales from 1 May 2018 in stages. It offers prompts and guidance to assist people in completing their application, and uses clear, non-technical language. This digital system runs alongside the existing paper application.

Cases which were started between May 2018 and January 2019 would only have the petitions submitted online. This means whilst petitions may have been issued online, subsequent steps would have been via paper using the existing non-digital processes.

From January 2019 the online service was extended in stages to cover the response to the divorce (known as the Acknowledgement of Service) and the application for decree nisi (done in stages between January and April 2019). From June 2019 the online service was further enhanced with the included the ability for the legal advisor to approve the entitlement for the divorce with automatic generation of the order then the decree nisi order at the pronouncement stage. The decree absolute was also made available online from July 2019.

For solicitors there was a small pilot that has been in operation from last July 2018 for the petition online. Since June 2019 the response to the divorce and application for decree nisi is also available. Further enhancements to include the decree nisi and decree absolute rolled out nationally in September 2019 following a small pilot.

Revision notice: There is an issue with a number of paper cases being flagged as digital cases following the change to define ‘digital cases’ as being digital at all stages (i.e. handled by the Courts and Tribunals Service Centres) in FCSQ Q1 2020 (released June 2020). This issue remains under investigation and, in line with the Code of Practice on Statistics, the Chief Statistician and Head of Profession has decided to withdraw the digital/paper split this quarter until the investigations are complete and a revised set of figures can be derived from the administrative data system.

7. Financial remedy (formerly ‘ancillary relief’) – financial disputes post-divorce/separation

During a divorce, a marriage annulment, a judicial separation, or the dissolution of a civil partnership there may still be a need for the court to settle disputes over money or property. The court can make a financial remedy order, formerly known as ‘ancillary relief’. These orders include dealing with the arrangements for the sale or transfer of property, maintenance payments, a lump sum payment or the sharing of a pension. Orders for financial provision other than for ancillary relief are not dependent upon divorce proceedings and may be made for children.

The Child Maintenance and Other Payments Act 2008 led to the creation of the Child Maintenance Enforcement Commission (CMEC) which replaced the Child Support Agency (CSA), although the CSA retained its existing caseload. The Act also removed the requirement for all parents in receipt of benefit to go through the CMEC even if they could reach agreement. Parents who were not on benefits were previously allowed to come to courts for consent orders. This change is likely to increase the number of parties that come to court for maintenance consent orders.

If an order is breached, several options are open to the aggrieved party to seek enforcement of the order. For money orders, proceedings can be instituted in the family court where a variety of remedies such as attachment of earnings may be available. However, if arrears of more than one year are owed, the person seeking payment must first get the court’s permission to make an enforcement application.

Please note that data in Table 16 previously looked at financial remedy disposals, (which includes orders made and dismissals) by remedy type. However, during to differing ways of requesting these on the application (some request all types, either to have an order made or to be dismissed, others just request the type they require the order for), it has been deemed that the quality of this data is not suitable for publication in a National Statistics bulletin. Work is ongoing to collect robust data on orders made and this will be reported on when available.

Within table 15 a split is given between contested and uncontested financial remedy applications. Where the first application lodged in a financial remedy case is for a consent order the case is considered to be uncontested, otherwise the case is considered to be contested.

8. Domestic violence remedy orders

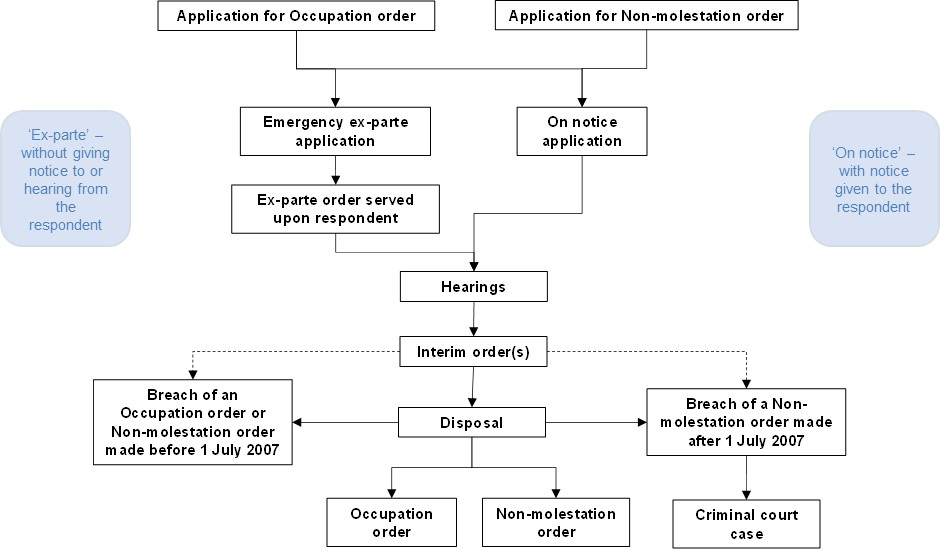

Part IV of the Family Law Act 1996 provides single and unified domestic violence remedies in the family court and the High Court, with the vast majority carried out in the former. Figure 3 shows the main court processes for domestic violence remedy cases.

A range of people can apply to the court: spouses, cohabitants, ex-cohabitants, those who live or have lived in the same household (other than by reason of one of them being the other’s employee, tenant, lodger or boarder), certain relatives (for example, parents, grandparents, in-laws, brothers, sisters), and those who have agreed to marry one another.

Two types of order can be granted:

- a non-molestation order, which can either prohibit particular behaviour or general molestation by someone who has previously been violent towards the applicant and/or any relevant children; and,

- an occupation order, which can define or regulate rights of occupation of the home by the parties involved.

In July 2007, section 1 of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004 came into force, making the breach of a non-molestation order a criminal offence. A power of arrest is therefore no longer required on a non-molestation order but instead it includes a penal notice. The court may also add an exclusion requirement to an emergency protection order or interim care order made under the Children Act 1989. This means a suspected abuser may be removed from the home, rather than the child.

Where the court makes an occupation order and it appears to the court that the respondent has used or threatened violence against the applicant or child, then the court must attach a power of arrest unless it is satisfied that the applicant or child will be adequately protected without such a power. If there is no power of arrest attached to the order, and the order is breached, this is dealt with as contempt of court. The court may then impose a fine or make a committal order whereby the person who breached the order is imprisoned or put on remand until the next hearing.

Figure 3: The main court processes for domestic violence remedy cases

9. Forced marriage protection orders

Applications for a Forced Marriage Protection Order (FMPO) can be made at 15 designated locations of the family court. This court, as well as the High Court, is able to make Forced Marriage Protection Orders to prevent forced marriages from occurring and to offer protection to victims who might have already been forced into a marriage.

From 16 June 2014, it is an offence to force a person to marry against their will, or to breach a FMPO. As a result, courts no longer need to attach a power of arrest to an FMPO, and so are no longer included in the relevant table.

From October-December 2018, there is a marked increase in the number of FMPOs made compared to the number of applications. Often there are multiple orders granted per case, where one application covers more than one person, and an order is granted for each person covered in the application. Extensions and increased provision of previous orders can also be granted as new orders, without the need for a new application to be submitted.

10. Female genital mutilation protection orders

Female Genital Mutilation Protection Orders (FGMPOs) are intended to safeguard girls who are at risk of FGM at home or abroad, or who are survivors. They came into effect on 17 July 2015.

11. Adoption

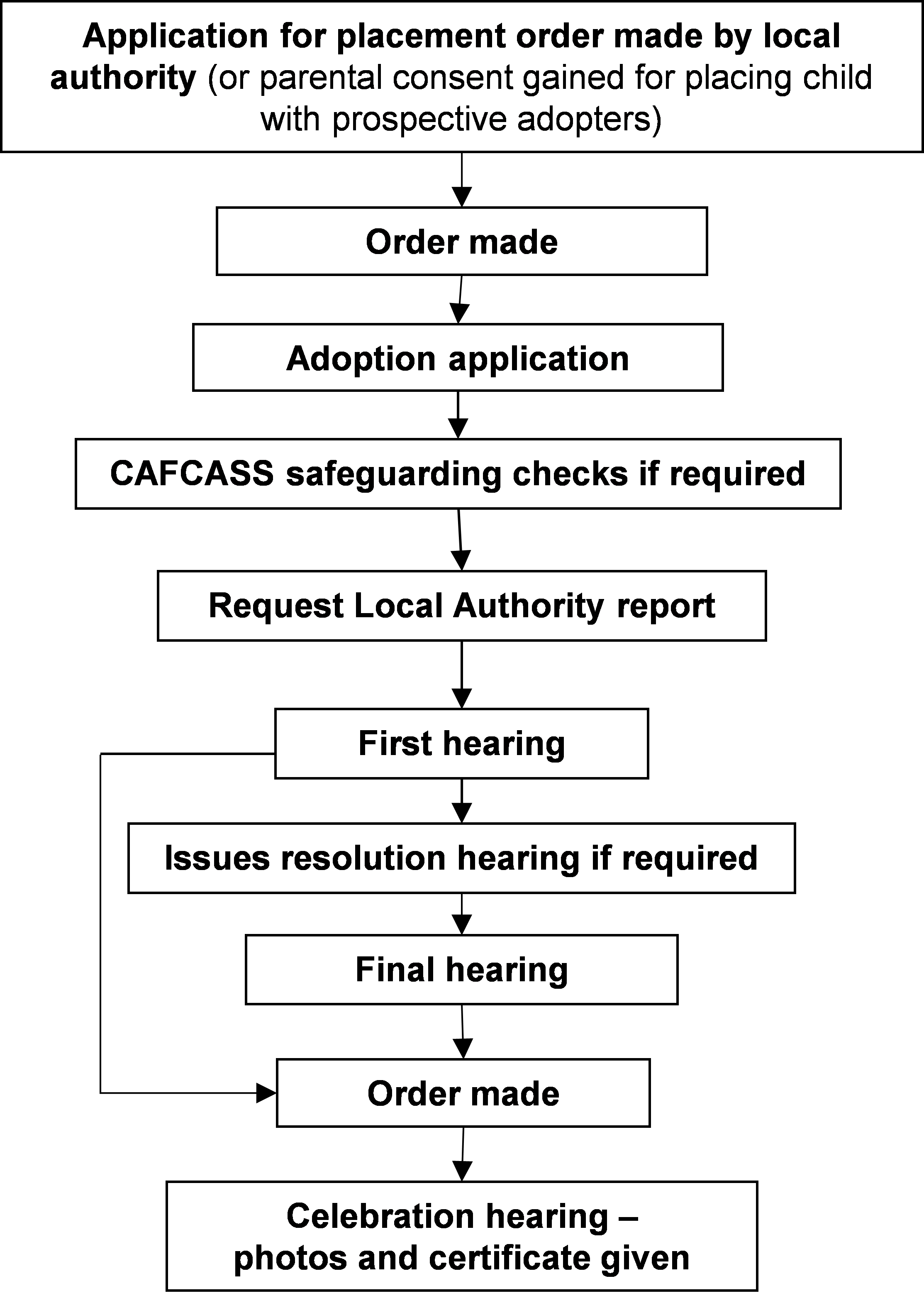

Prior to making an adoption application, a placement order is generally made to place a child with prospective adopters. If the placement is being made by an adoption agency, by a High Court order, or by the child’s parent, the placement period is 10 weeks before an adoption application can be made. For a step-parent, the placement duration is six months, while for local authority foster parents, it is usually one year. In other cases, the courts generally require the child to have been living with the prospective adopters for three out of the preceding five years. An application for adoption can be made to the family court in the area in which the child is living.

An adoption order made by a court extinguishes the rights, duties and obligations of the natural parents or guardian and vests them in the adopters. On the conclusion of an adoption the child becomes, for virtually all purposes in law, the child of its adoptive parents and has the same rights of inheritance of property as any children born to the adoptive parents. Figure 4 shows the main court processes for adoption cases.

Until 2012, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) published adoption figures annually.

Figure 4: The main court processes for adoption cases

12. The Mental Capacity Act

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a statutory framework to empower and protect vulnerable people who are not able to make their own decisions. It makes it clear who can take decisions, in which situations, and how they should go about this. It enables people to plan ahead for a time when they may lose capacity.

The Act created two new public bodies to support the statutory framework, both of which are designed around the needs of those who lack capacity.

- The Court of Protection

- The Public Guardian, supported by the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG)

12.1 The Court of Protection

The Court of Protection makes specific decisions, and also appoints other people (called deputies) to make decisions for people who lack the capacity to do this for themselves. These decisions are related to their property, financial affairs, health and personal welfare. The Court of Protection has powers to:

- make declarations about a person’s capacity to make a particular decision, if the matter cannot be decided informally;

- make decisions about serious medical treatment, which relate to providing, withdrawing or withholding treatment to a person who lacks capacity;

- make decisions or orders about the personal welfare and property and affairs of people who lack capacity to make such decisions themselves;

- authorise deprivation of liberty in relation to a person’s care and residence arrangements;

- appoint a deputy to make ongoing decisions for people lacking capacity to make those decisions in relation to their personal welfare or property and financial affairs;

- make decisions about a Lasting Power of Attorney or Enduring Power of Attorney, including whether the power is valid, objections to registration, the scope of attorney powers and the removal of attorney powers.

Most applications to the court are decided on the basis of paper evidence without holding a hearing. In around 95% of cases, the applicant does not need to attend court. Some applications such as those relating to personal welfare, objections in relation to deputies and attorneys, or large gifts or settlements for Inheritance Tax purposes may be contentious and it will be necessary for the court to hold a hearing to decide the case.

Following the introduction of new forms in July 2015, applicants must make separate applications for ‘property and affairs’ and ‘personal welfare’, resulting in the almost complete absence of ‘hybrid deputy’ applications since Q4 2015.

Applications relating to deprivation of liberty increased following the Supreme Court decision on 19 March 2014[footnote 4] whereby it was considered a person could be deprived of their liberty in their own home, sheltered accommodation etc., and not just the nursing homes and hospitals which were previously covered.

In Re X and others [2014] EWCOP25, the Court of Protection set out a new streamlined process to enable courts to deal with deprivation of liberty cases in a timely and just fashion. Half of applications for deprivation of liberty were made under this process.

NHS Digital publishes official statistics on the Mental Capacity Act 2005, Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards data collection. This includes any application to local authorities reported to NHS Digital that was received, processed or considered to be “active” in any way during the year.

12.2 Office of the Public Guardian

The Office of the Public Guardian (OPG), an agency of the Ministry of Justice, was established in October 2007, and supports the Public Guardian in registering Enduring Powers of Attorney (EPA), Lasting Powers of Attorney (LPA) and supervising Court of Protection (COP) appointed Deputies.

The OPG supports and promotes decision making for those who lack capacity or would like to plan for their future, within the framework of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. The role of the Public Guardian is to protect people who lack capacity from abuse. The Public Guardian, supported by the OPG, helps protect people who lack capacity by:

- setting up and managing a register of LPA and EPA

- setting up and managing a register of Court appointed Deputies, supervising Court appointed Deputies, working with other relevant organisations (for example, social services, if the person who lacks capacity is receiving social care);

- receiving annual financial reports from all primary Deputies under their supervision; and

- dealing with cases, by way of investigations, where concerns are raised about the way in which Attorneys or Deputies are carrying out their duties.

13. Probate

When a person dies, somebody has to deal with their estate (money property and possessions left) by collecting in all the money, paying any debts and distributing what is left to those people entitled to it. Probate is the court’s authority; given to a person or persons to administer a deceased person’s estate and the document issued by the Probate Service is called a Grant of Representation. This document is usually required by the asset holders as proof to show the correct person or persons have the Probate Service’s authority to administer a deceased person’s estate.

Grants of representation are known as either:

- Probate – when the deceased person left a valid will and an executor is acting,

- Letters of administration with will – when a person has left a valid will but no executor is acting, or

- Letters of administration – usually when there is no valid will.

These different types of grants of representation appoint people known as personal representatives to administer the deceased person’s estate.

When a Probate is contested, the Chancery Division of the High Court deals with the matter. See the Guide to Civil and Administrative Justice Statistics for more information on the Chancery Division.

Grants of representation can be applied for digitally (and handled by the Courts and Tribunals Service Centre) or via the traditional paper route. The CTSC have trained substantial numbers of new staff and now has now got a broad multi skilled team who can process probate applications more quickly and accurately than previously.

Timeliness measures for grants of representation are provided in FCSQ from application submission and document receipt (which occurs after payment has been made and all accompanying paperwork has been received by HMCTS). For digital applications the receipt is instant but no work can start until the Will is sent to us. Therefore, for digital cases the measure of waiting times is from document receipt rather than the application submission.

Please note that the HMCTS database which collects information on probate changed in May 2019. However, due the transition between the old and new systems, it was not possible to provide the breakdown by grant type and applicant type for quarter 2 of 2019 (and as such, for 2019 as a whole). As a guide only, Q2 2019 estimates have been provided in Table 26 based on the average across 2016 to 2018, and these estimates then feed into the 2019 total.

14. Data Sources and Data Quality

14.1 Data Sources

The data on family related court cases is principally sourced from the court administrative system, FamilyMan, used by court staff for case management purposes. It contains good quality information about a case’s progress through the family courts.

For earlier years, FamilyMan provided data for county courts and for the Family Proceedings Courts which share premises and administrative systems with county courts; data for other Family Proceedings Courts was provided on electronic summary returns submitted to HMCTS Business Information Division on a monthly basis. Figures prior to 2007 for Family Proceedings Courts were weighted estimates based on data from a subset of courts. There are known data quality problems with these, which are likely to be an undercount. Starting at the end of 2009, an upgrade to the administrative system in all county courts and Family Proceedings Courts was rolled out nationally. This upgrade was completed in December 2010 following a staggered rollout. Therefore, the majority of the family court case data now comes from the FamilyMan system.

Whilst the Ministry of Justice’s divorce statistics are sourced directly from the FamilyMan system, the ONS data used to be compiled from ‘D105’ forms used by the courts to record decrees absolute. There were small differences between the number of divorces as recorded by the two sets of statistics, and attempts were made to understand these differences and reconcile where possible. A joint statement was subsequently produced by the MoJ and ONS on the differences in these divorce statistics, which can be found at Annex C of the CSQ bulletin for Q1 2012.

Information on Forced Marriage Protection Orders (FMPOs) and Female Genital Mutilation Protection Orders (FGMPOs) are sourced from the HMCTS Performance database (OPT). This is a regularly updated, web-based management information system which enables aggregation to national level of returns from individual courts. It is based on systems similar to FamilyMan, that is court administrative systems used for case management.

Mental Capacity Act figures are provided directly to MoJ from the Court of Protection (CoP) and the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) from their data management systems. Information about Lasting Power of Attorney records (LPAs) is managed by OPG’s Sirius case management system. Sirius is the first case management system in government developed using Government Digital Service principles; it is built with open source technologies, cloud hosted and maintained by teams in OPG.

Probate figures from Q2 2019 onwards are extracted from the new Core Case Data system that was implemented in May 2019. Earlier data was extracted from HMCTS’s OPT system, which utilised data from ProbateMan – a similar administrative system to FamilyMan.

14.2 Counting Rules

Here are some main points to consider when interpreting the family court statistics:

- A disposal which occurs in one quarter or year may relate to an application which was initially made in an earlier period. Additionally, an application of one type may lead to an order of a different type being made.

- As well as an order made, a disposal can be a refused order, withdrawn application, or order of no order.

- There are several ways to analyse and count the data on family cases. By case – where each case number in FamilyMan is only counted once. By application or disposal - where each application or disposal is only counted once. Please note counting applications or disposals by type will not sum to the overall total as an application or disposal may include more than one type. By the number of children involved - the data on Public law and Private law proceedings is also analysed by the number of children which are subject to an application or disposal - for example, if two children are the subject of a single case then the children would be counted separately in those statistics. Different types of orders may be made in respect of different children involved in a case.

Breakdowns of many of the summary figures presented in FCSQ, such as splits by case type or by Designated Family Judge (DFJ) area, are available in the Comma Separated Value (csv) files that accompany the bulletin.

Symbols and conventions

The following symbols have been used throughout the tables in this bulletin:

.. = Not applicable

- = Not available

0 = Nil

14.3 Data Quality

Family court statistics are published in compliance with the Ministry of Justice quality strategy, principles and processes for statistics, which states that information should be provided as to how the bulletin meets user needs.

Five principles (relevance, accuracy, timeliness, accessibility and clarity, comparability and coherence) are outlined. The Data Quality statement which accompanies this guide addresses how each are addressed in the FCSQ publications.

15. National Statistics accreditation

The United Kingdom Statistics Authority has designated these statistics in FCSQ as National Statistics, in accordance with the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 and signifying compliance with the Code of Practice for Official Statistics.

The continued designation of these statistics as National Statistics was confirmed in January 2019[footnote 5] following a compliance check by the Office for Statistics Regulation. The statistics last underwent a full assessment against the Code of Practice in 2010[footnote 6] when this information was previously published as part of the Court Statistics Quarterly collection.

Designation can be broadly interpreted to mean that the statistics:

- meet identified user needs;

- are well explained and readily accessible;

- are produced according to sound methods, and

- are managed impartially and objectively in the public interest.

Once statistics have been designated as National Statistics, it is a statutory requirement that the Code of Practice shall continue to be observed.

15.1 Revisions

In accordance with Principle 2 of the Code of Practice for Statistics, the Ministry of Justice is required to publish transparent guidance on its policy for revisions.

The three reasons specified for statistics needing to be revised are;

- changes in sources of administrative systems or methodology changes

- receipt of subsequent information, or

- errors in statistical systems and processes.

Each of these points, and its specific relevance to the FCSQ publication, are addressed below.

Changes in source of administrative systems/methodology changes

The data within this publication come from a variety of administrative systems. This technical document will clearly present where there have been revisions to data due to changes in methodology or administrative systems. In addition, statistics affected within the publication will be appropriately footnoted or additional text included to explain and quantify the impact of said changes.

As the data underlying Family Court Statistics Quarterly (FCSQ) are extracted from a live administrative database, figures are subject to revision in future publications. For tables that use information from the FamilyMan system, data are extracted for the full timeseries within each bulletin. Minimal changes (i.e. a handful of cases) may be observed in earlier years, whilst larger changes are seen in the most recent quarters as cases progress further through the system. This is especially relevant for case progression tables (Tables 8-10).

Receipt of subsequent information

The nature of any administrative system is that data may be amended or received late. For the purpose of FCSQ, late or amended data of any previously published periods will be incorporated to reflect the up to date ‘live’ FamilyMan database, as described in the revisions section above.

Errors in statistical systems and processes

Occasionally errors can occur in statistical processes; procedures are constantly reviewed to minimise this risk. Should a significant error be found, the publication on the website will be updated and appropriate notifications documenting the revision will be made.

16. Users of the statistics

Official statistics are used by a wide range of individuals and organisations, and their value lies in their wide and informed use. The main users of these statistics are Ministers and officials in central government responsible for developing policy regarding family justice. Other users include the central government departments, and various voluntary organisations with an interest in family justice. The data also feeds into statistics produced by the Office for National Statistics, such as public-sector productivity and the Domestic Violence in England and Wales bulletin.

We routinely consult with policy and operational colleagues to refresh our understanding of core uses for the data, promote the release and provide support to known users. We seek comments from external users and maintain dialogue with public users via a dedicated email account that is included in this guide and in every bulletin and accompanying data visualisation tool for feedback on the commentary and any additional wider feedback or queries.

17. Legislation coming into effect in the reporting period

The legislation described below relates mainly to legislation that came into force since 2000. It is only a brief summary of the sections that may have affected the published statistics. www.legislation.gov.uk has details of all legislation that has come into force in the intervening period.

The coverage of the statistics in this publication may have been affected by the following legislation:

- Adoption and Children Act 2002

- Civil Partnership Act 2004

- Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004

- Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act 2007

- Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012

- Crime and Courts Act 2013

- Children and Families Act 2014

- Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014

17.1 Adoption and Children Act 2002

The Adoption and Children Act 2002 was implemented on 30 December 2005, replacing the Adoption Act 1976. It made amendments to the law in relation to the adoption of children. The first stage of the Act deals with Local Authorities duties to provide an adoption service and support services. The second stage relating to inter-country adoptions and the third stage relates to Adoption Support Services. Changes to parental responsibility and the adopted children register were also made. The key changes resulting from the new act were the:

- alignment of adoption law with the Children Act 1989 to ensure that the child’s welfare is the most important consideration when making decisions;

- provision for adoption orders to be made in favour of unmarried couples;

- the introduction of Special Guardianship Orders, intended to provide permanence for children for whom adoption is not appropriate.

17.2 Civil Partnership Act 2004

The Civil Partnership Act 2004 grants civil partnerships in the United Kingdom with rights and responsibilities identical to civil marriage. Civil Partners are entitled to the same property rights as married opposite-sex couples, the same exemption as married couples with regard to social security and pension benefits, and also the ability to get parental responsibility for a partner’s children, as well as responsibility for reasonable maintenance of one’s partner and their children, tenancy rights, full life insurance recognition, next-of-kin rights in hospitals, and others. There is a formal process for dissolving partnerships akin to divorce.

17.3 Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004

The Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004 concentrates upon legal protection and assistance to victims of crime, particularly domestic violence.

17.4 Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act 2007

The Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act 2007 seeks to assist victims of forced marriage, or those threatened with forced marriage, by providing civil remedies. The Act created the forced marriage protection order (FMPO). A person threatened with forced marriage can apply to court for a forced marriage protection order. The court can then order a range of appropriate provisions to prevent the forced marriage from taking place, or to protect a victim of forced marriage from its effects, and may include such measures as confiscation of passport or restrictions on contact with the victim.

The subject of a forced marriage protection order can be not just the person to whom the forced marriage will occur, but also any other person who aids, abets or encourages the forced marriage. A marriage can be considered forced not merely on the grounds of threats of physical violence to the victim, but also through threats of physical violence to third parties (for example, the victim’s family), or even self-violence (for example, marriage procured through threat of suicide.) A person who violates a forced marriage protection order is subject to contempt of court proceedings and may be arrested.

17.5 Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012

Following the introduction of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 on 1 April 2013, the scope of services funded as part of civil legal aid changed. For family law, the general position is that Public law proceedings and the representation of children remain in scope under Part 1, Schedule 1 of LASPO. However, most private family law cases involving children or finance remain in scope only where there are issues concerning domestic violence or child abuse and specific evidence fulfilling the requirements of regulation 33 or 34 of the Procedure Regulations is provided in support of this.

17.6 Crime and Courts Act 2013

The Crime and Courts Act 2013 established the single Family Court, replacing the previous three-tiered system under which cases were heard in family proceedings courts, Country Courts and the High Court.

17.7 Children and Families Act 2014

The Children and Families Act 2014 made a number of changes affecting Public law family cases. In particular, it introduced a 26 week time limit for completing care and supervision cases. It gave the family court the discretion to extend cases by up to 8 weeks at a time should that be necessary to resolve proceedings justly. The Act also removed the need to review interim care orders and interim supervision orders as frequently, allowing the courts to set interim orders in line with the timetable for the case. In relation to Private law matters, the Act introduced a ‘child arrangements order’, replacing residence and contact orders. It also removed the requirement for the court to consider arrangements for children as part of the court processes for divorce and dissolution of a civil partnership.

17.8 Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014

The Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 came into force on 16 June 2014 and made it an offence to force a person to marry against their will, or to breach a FMPO.

18. Directory of Related Internet Websites on the Family Court

The following list of web sites contains information in the form of publications and/or statistics relating to the family justice system that may be of interest.

Ministry of Justice: This site provides information on the organisations within the justice system, reports and data, and guidance.

Ministry of Justice Statistical and Research publications: Most of the publications can be viewed online.

Attorney General’s Office: Provides information on the role of the department including new releases; updates; reports; reviews and links to other law officer’s departments and organisations.

Welsh Assembly Government: Gives information on all aspects of the Welsh Assembly together with details of publications and statistics.

Scottish Government: Gives information on all aspects of the Scottish Executive together with details of publications and statistics.

UK National Statistics Publication Hub: This is the UK’s home of official statistics, reflecting Britain’s economy, population and society at national and local level. There are links to the Office for National Statistics and the UK Statistics Authority.

Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (CAFCASS): A non-departmental public body set up to promote the welfare of children and families involved in family court.

The Nuffield Foundation has established a Family Justice Observatory that will support the best possible decisions for children by improving the use of data and research evidence in the family justice system in England and Wales.

19. Glossary

19.1 Application

The act of asking the court to make an order.

19.2 Child Arrangements Order

A child arrangements order regulates the arrangements for who a child is to live with, spend time with or otherwise have contact with when parents separate. It effectively combines residence and contact orders and reduces the feeling that one parent has more say in the upbringing of the child because they have a residence order. The order contains a warning notice about failure to comply with the order and will be subject to enforcement in the same way as a contact order is currently. The child arrangements order replaced residence orders and contact orders from 22 April 2014.

19.3 Convention Adoption

An adoption carried out under the terms of The Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. This is an international treaty designed to protect children from child trafficking, and requires signatory countries to establish safeguards to ensure that any inter-country adoption is in the child’s best interests.

19.4 Decree Absolute

This is the final order made in divorce proceedings that can be applied for six weeks and one day after a decree nisi has been given. Once this is received, the couple are no longer legally married and are free to remarry.

19.5 Decree Nisi

This is the first order made in divorce proceedings and is given when the court is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for granting the divorce. It is used to apply for a decree absolute.

19.6 Deputyships

A Deputy (OPG) is legally responsible for acting and making decisions on behalf of a person who lacks capacity to make decisions for themselves. The Deputy order sets out specific powers in relation to the person who lacks capacity.

19.7 Dissolution

The legal termination of a marriage by a decree of divorce, nullity or presumption of death or of a civil partnership by the granting of a dissolution order.

19.8 Digital divorce

Where a divorce has been dealt with digitally by a Courts and Tribunal Service Centre at all stages of the divorce process.

19.9 Divorce

This is the legal ending of a marriage.

19.10 Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA)

An EPA is a legal document that allows someone (the ‘donor’) to appoint one or more people (known as ‘attorneys’) to make decisions about their property or money, at a time in the future when they either lack the mental capacity or no longer wish to make those decisions themselves. EPAs were replaced by lasting powers of attorney on 1st October 2007. Only EPAs made and signed before this date can still be used.

19.11 Financial Remedy

Formerly known as Ancillary Relief. This refers to different types of order used to settle financial disputes during divorce proceedings. Examples include: periodical payments, pension sharing, property adjustment and lump sums, and they can be made in favour of either the former spouse or the couple’s children.

19.12 Judicial Separation

This is a type of order that does not dissolve a marriage but absolves the parties from the obligation to live together. This procedure might, for instance, be used if religious beliefs forbid or discourage divorce.

19.13 Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA)

An LPA is a legal document that allows someone (the ‘donor’) to appoint one or more people (known as ‘attorneys’), that they trust to make decisions on their behalf, at a time in the future when they either lack the mental capacity or no longer wish to make those decisions themselves.

19.14 Non-molestation Order

This is a type of civil injunction used in domestic violence cases. It prevents the applicant and/or any relevant children from being molested by someone who has previously been violent towards them. Since July 2007, failing to obey the restrictions of these orders has been a criminal offence for which someone could be arrested.

19.15 Nullity

This is where a marriage is ended by being declared not valid. This can either be because the marriage was void (not allowed by law) or because the marriage was voidable (the marriage was legal but there are circumstances that mean it can be treated as if it never took place).

19.16 Occupation Order

This is a type of civil injunction used in domestic violence cases. It restricts the right of a violent partner to enter or live in a shared home.

19.17 Order

The document bearing the seal of the court recording its decision in a case. Some examples of orders are below:

Care orders

A care order brings the child into the care of the applicant local authority and cannot be made in favour of any other party. The care order gives the local authority parental responsibility for the child and gives the local authority the power to determine the extent to which the child’s parents and others with parental responsibility (who do not lose their parental responsibility on the making of the order) may meet their responsibility. The making of a care order, with respect to a child who is the subject of any section 8 order, discharges that order.

Supervision orders

A supervision order places the child under the supervision of the local authority or probation officer. While a supervision order is in force, it is the duty of the supervisor to advise, assist and befriend the child and take the necessary action to give effect to the order, including whether or not to apply for its variation or discharge

Emergency Protection Orders

An emergency protection order is used to secure the immediate safety of a child by removing the child to a place of safety, or by preventing the child’s removal from a place of safety. Anyone, including a local authority, can apply for an emergency protection order if, for example, they believe that access to the child is being unreasonably refused.

19.18 Petition (for divorce)

An application for a decree nisi or a judicial separation order.

19.19 Private Law

Refers to Children Act 1989 cases where two or more parties are trying to resolve a private dispute. This is commonly where parents have split-up and there is a disagreement about who their children should live with and who their children should have contact with, or otherwise spend time with and when.

19.20 Public Law

Refers to Children Act 1989 cases where there are child welfare issues and a local authority, or an authorised person, is stepping in to protect the child and ensure they get the care they need. Section 8 orders: Under the Children Act 1989, Section 8 orders refer to child arrangement orders (contact and residence), prohibited steps and specific issue orders.

20. Contacts

Enquiries about this guide should be directed to the Data and Evidence as a Service division of the MoJ:

Carly Gray, Head of Access to Justice Data and Statistics Email: familycourt.statistics@justice.gov.uk

General enquiries about the statistics work of the MoJ can be e-mailed to statistics.enquiries@justice.gov.uk

General information about the official statistics system of the UK is available from www.statistics.gov.uk

Press enquiries should be directed to the Ministry of Justice press office:

Tel: 020 3334 3536

Email: newsdesk@justice.gsi.gov.uk

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20081208061525/http://www.haringey.gov.uk:80/index/news_and_events/latest_news/childa.htm ↩

-

Under the Children Act 1989, Section 8 orders refer to child arrangement orders (contact and residence), prohibited steps and specific issue orders. ↩

-

As from the publication of the January to March 2017 bulletin. ↩

-

P v Cheshire West and Chester Council and P and Q v Surrey County Council [2014] UKSC 19 ↩

-

https://www.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/correspondence/compliance-check-on-court-statistics/ ↩

-

https://www.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/publication/statistics-on-court-activity/ ↩