Offploy report (HTML version)

Published 31 October 2024

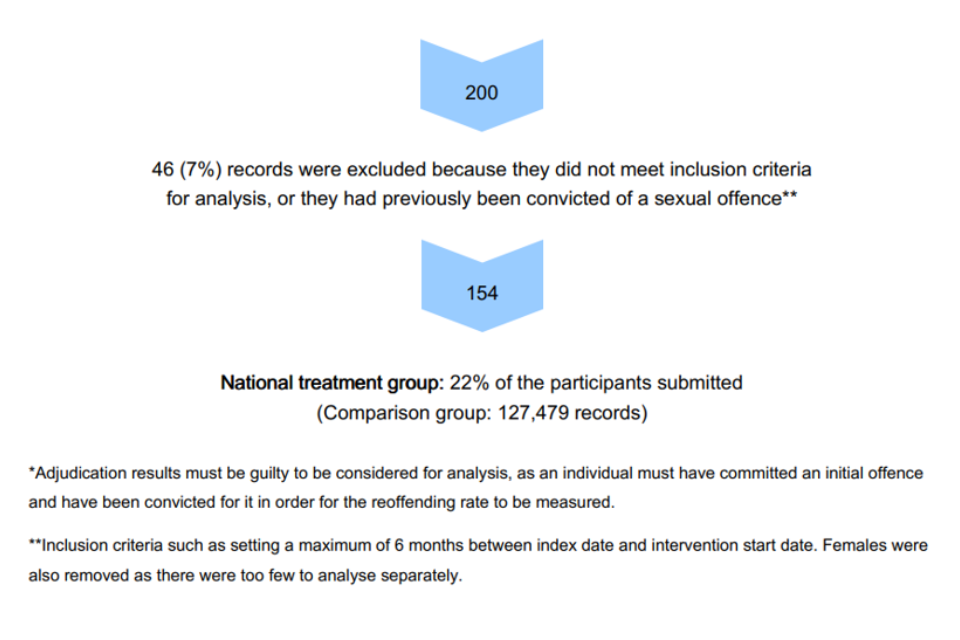

This analysis looked at the reoffending behaviour of 154 men participating in Offploy’s programme of support. It covers those who began the programmes either through-the-gate or in the community between 2019 and 2022. The overall results show that those who took part in the Offploy programmes had a lower offending frequency compared to a matched comparison group. This is a statistically significant result. More people would be need to be analysed to determine the way in which the programme affects the rate of reoffending and the time to first proven reoffence, but this should not be taken to mean that the programme fails to affect it.

The programmes of support provided by Offploy work with participants to identify and complete goals with the intention to move the participants closer to employment, improving mental wellbeing, confidence and mindset.

The headline analysis in this report measured proven reoffences in a one-year period for a ‘treatment group’ of 154 male offenders who began receiving support some time between 2019 and 2022, and for a much larger ‘comparison group’ of similar offenders who did not receive it. The analysis estimates the impact of the support from Offploy on reoffending behaviour.

1. Overall measurements of the treatment and comparison groups

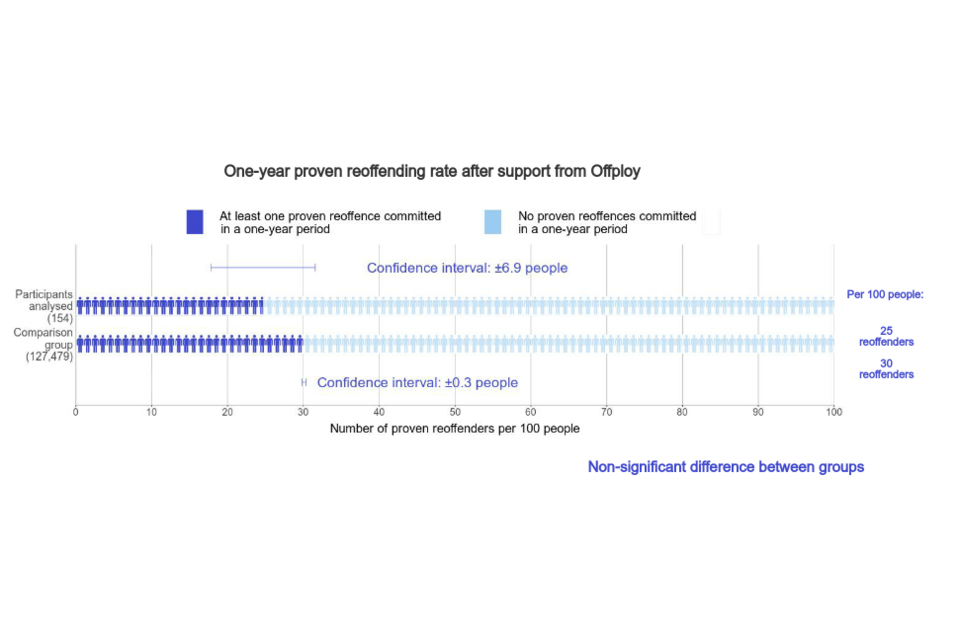

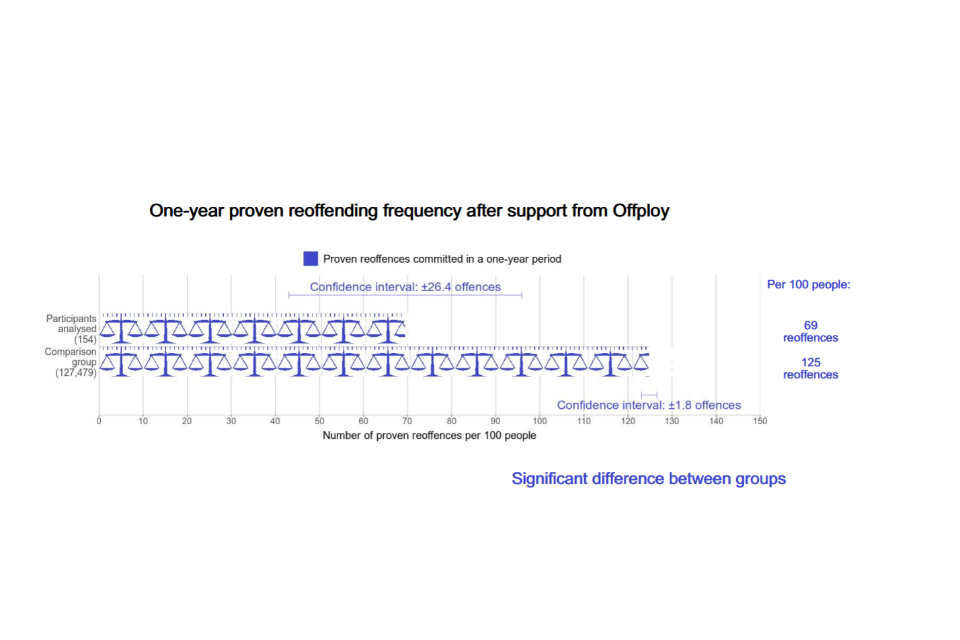

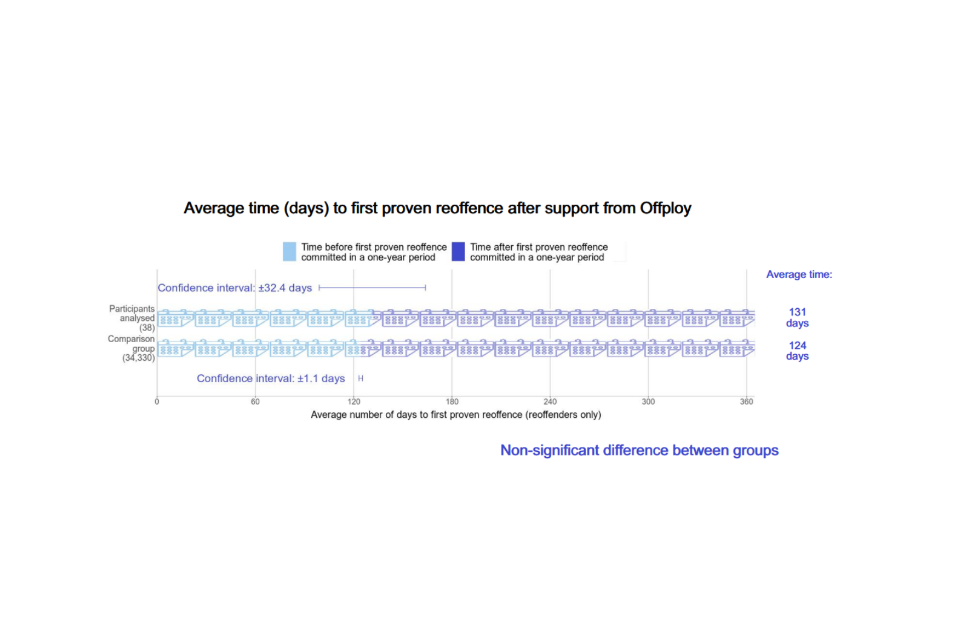

| For 100 typical men in the treatment group, the equivalent of: | For 100 typical men in the comparison group, the equivalent of: |

|---|---|

| 25 of the 100 men committed a proven reoffence within a one-year period (a rate of 25%), 5 men fewer than in the comparison group. | 30 of the 100 men committed a proven reoffence within a one-year period (a rate of 30%). |

| 69 proven reoffences were committed by these 100 men during the year (a frequency of 0.7 offences offences per person), 55 offences fewer than in the comparison group. | 125 proven reoffences were committed by these 100 men during the year (a frequency of 1.2 offences per person). |

| 131 days was the average time before a reoffender committed their first proven reoffence, 7 days later than the comparison group. | 124 days was the average time before a reoffender committed their first proven reoffence. |

Please note totals may not appear to equal the sum of the component parts due to rounding.

2. Overall estimates of the impact of the intervention

| For 100 typical men who receive support, compared with 100 similar men who do not: | |

|---|---|

| The number of men who commit a proven reoffence within one year after release could be lower by as many as 12 men, or higher by as many as 1 man. More men would need to be available for analysis in order to determine the direction of this difference. | |

| The number of proven reoffences committed during the year could be lower by between 29 and 82 offences. This is a statistically significant result. | |

| On average, the time before an offender committed their first proven reoffence could be shorter by as many as 25 days, or longer by as many as 40 days. More men would need to be analysed in order to determine the direction of this difference. |

| ✔ | What you can say about the one-year reoffending rate: |

|---|---|

| “This analysis does not provide clear evidence on whether support from Offploy increases or decreases the number of participants who commit a proven reoffence in a one-year period. There may be a number of reasons for this and it is possible that an analysis of more participants would provide such evidence.” | |

| ✖ | What you cannot say about the one-year reoffending rate: |

| “This analysis provides evidence that support from Offploy increases / decreases / has no effect on the reoffending rate of its participants.” | |

| ✔ | What you can say about the one-year reoffending frequency: |

| “This analysis provides evidence that support from Offploy decreases the number of proven reoffences committed during a one-year period by its participants.” | |

| ✖ | What you cannot say about the one-year reoffending frequency: |

| “This analysis provides evidence that support from Offploy increases/has no effect on the number of reoffences committed by its participants.” | |

| ✔ | What you can say about the time to first reoffence: |

| “This analysis does not provide clear evidence on whether support from Offploy shortens or lengthens the average time to first proven reoffence. There may be a number of reasons for this and it is possible that an analysis of more participants would provide such evidence.” | |

| ✖ | What you cannot say about the time to first reoffence: |

| “This analysis provides evidence that support from Offploy shortens / lengthens / has no effect on the average time to first proven reoffence for its participants.” |

3. Figure 1: One-year proven reoffending rate after support from Offploy

4. Figure 2: One-year proven reoffending frequency after support from Offploy

5. Figure 3: Average time (days) to first proven reoffence after support from Offploy

6. Offploy in their own words

“The programmes of support provided by Offploy work with participants to identify and complete goals with the intention to move the participants closer to employment, improving mental wellbeing, confidence and mindset.

The intervention comprises an initial assessment to assess the candidate’s needs and aspirations. From this, an action plan is created for the candidate with SMART goals to move them along the 9-step journey.

Each goal is defined by the candidate’s needs and it is expected that the candidate will take full accountability of these goals throughout the provision. Throughout their journey, candidates have at least weekly face to face or telephone meetings with the peer mentor to recap on progress made, review and amend goals and provide support in progression through the programme. This support identifies training and job opportunities although it may also be as simple as referring them to housing providers or obtaining food bank vouchers where it is considered to be a need.

The intention is to move the candidate closer to employment, improving mental wellbeing, confidence and mindset. This can be done through many channels of support and Offploy’s programmes of support use community service and partners to signpost candidates for specialist/support needs. Each of the candidates submitted has completed a minimum of one goal.”

7. Response from Offploy to the Justice Data Lab analysis

“We are pleased to see the findings from Offploy’s first analysis conducted by the Justice Data Lab (JDL). This analysis covers the outcomes of 154 male participants engaged in our programme between 2019 and 2022, marking an important step in evaluating our impact on reducing reoffending.

The results show a meaningful reduction in the frequency of reoffending among our participants, who committed fewer proven reoffences (0.7 offences per person) compared to a control group (1.2 offences per person) in a one-year period . The treatment group committed 55 reoffences fewer than the comparison group, an achievement we are proud to share. It reflects the hard work and dedication of the Offploy team and the value of the services we provide.

Although the proven reoffending rate within a one-year period was not statistically significant, (25% of Offploy participants reoffended, compared to 30% of the comparison group), we remain optimistic. These results, while impacted by the smaller dataset available at the time (due to our size in December 2022 and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic), offer a promising baseline for future growth. We see this as an initial step from which we will build upon and improve.

It is important to highlight that this report draws on data from previous years. Since then, we have made significant improvements to our data gathering and measurement processes. These enhancements, combined with our recent achievement of the Matrix Standard, underscore our commitment to delivering high-quality information, advice, and guidance to our candidates. We believe these efforts will be reflected in future evaluations.

Looking forward, we intend to submit an updated report next year, reflecting a larger dataset as we grow. The Justice Data Lab plays an invaluable role in helping us measure our social impact, and we are grateful for the insights this collaboration provides.

We encourage other organisations to consider using the Justice Data Lab to evaluate their impact on reoffending. The process has been instrumental in highlighting areas of success and identifying opportunities for further development. We would be happy to share our experiences and support others in navigating this process.”

We would like to extend our gratitude to the entire Offploy and JDL team for their dedication and hard work. Together, we are making a tangible difference, and this is only the beginning of what we can achieve in the years ahead.

8. Results in detail

One analysis was conducted, controlling for offender demographics and criminal history and the following risks and needs: accommodation, employment, financial management, relationships, lifestyle and associates, drug and alcohol use, mental health and thinking skills.

1. National analysis: treatment group matched to offenders across England using demographics, criminal history and individual risks and needs.

The sizes of the treatment and comparison groups for reoffending rate and frequency analyses are provided below. To create a comparison group that is as similar as possible to the treatment group, each person within the comparison group is given a weighting proportionate to how closely they match the characteristics of individuals in the treatment group. The calculated reoffending rate uses the weighted values for each person and therefore does not necessarily correspond to the unweighted figures.

| Analysis | Treatment Group Size | Comparison Group Size | Reoffenders in treatment group | Reoffenders in comparison group (weighted number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | 154 | 127,479 | 38 | 34,330 (38,353) |

In each analysis, three headline measures of one-year reoffending were analysed, as well as four additional measures (see results in Tables 1-7):

- Rate of reoffending

- Frequency of reoffending

- Time to first reoffence

- Rate of first reoffence by court outcome

- Frequency of reoffences by court outcome

- Rate of custodial sentencing for first reoffence

- Frequency of custodial sentencing

The standard acceptable level of statistical significance necessary to demonstrate impact is 0.05. This means that it is very unlikely with 5% probability that the difference between the treatment and comparison groups, as illustrated by the p-values in the tables below, could have occurred by chance alone.

Tables 1-7 show the overall measures of reoffending. Rates are expressed as percentages and frequencies expressed per person. Tables 3 to 7 include reoffenders only.

8.1 Table 1: Proportion of men who committed a proven reoffence in a one-year period (reoffending rate) after support from Offploy compared with a matched comparison group

| Number in treatment group | Number in comparison group | Treatment group rate (%) | Comparison group rate (%) | Estimated difference (% points) | Significant difference? | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 154 | 127,479 | 25 | 30 | -12 to 1 | No | 0.12 |

8.2 Table 2: Number of proven reoffences committed in a one-year period (reoffending frequency - offences per person) by men who received support from Offploy compared with a matched comparison group

| Number in treatment group | Number in comparison group | Treatment group frequency | Comparison group frequency | Estimated difference (% points) | Significant difference? | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 154 | 127,479 | 0.69 | 1.25 | -0.82 to -0.29 | Yes | <0.01 |

8.3 Table 3: Average time (days) to first proven reoffence in a one-year period for men who received support from Offploy, compared with a matched comparison group

| Number in treatment group | Number in comparison group | Treatment group time (days) | Comparison group time (days) | Estimated difference (% points) | Significant difference? | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | 34,330 | 131 | 124 | -25 to 40 | No | 0.66 |

8.4 Table 4: Proportion of men supported by Offploy with first proven reoffence in a one-year period (reoffending rate) by court outcome, compared with similar non-participants (reoffenders only)

| Number in treatment group | Number in comparison group | Court outcome | Treatment group time (days) | Comparison group time (days) | Estimated difference (% points) | Significant difference? | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | 34,330 | Either way | 42 | 55 | -30 to 3 | No | 0.12 |

8.5 Table 5: Number of proven reoffences in a one-year period (reoffending frequency) by court outcome for men supported by Offploy, compared with similar non-participants (reoffenders only)

| Number in treatment group | Number in comparison group | Court outcome | Treatment group frequency | Comparison group frequency | Estimated difference (% points) | Significant difference? | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | 34,330 | Either way | 1.42 | 2.38 | -1.67 to -0.24 | Yes | 0.01 |

| Summary | 0.71 | 1.03 | -0.71 to 0.07 | No | 0.11 |

8.6 Table 6: Proportion of men who received a custodial sentence for their first proven reoffence after support from Offploy, compared with similar non-participants (reoffenders only)

| Number in treatment group | Number in comparison group | Treatment group rate (%) | Comparison group rate (%) | Estimated difference (% points) | Significant difference? | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | 34,330 | 50 | 51 | -18 to 15 | No | 0.86 |

8.7 Table 7: Number of custodial sentences received in a one-year period by men who received support from Offploy, compared to similar non-participants (reoffenders only)

| Number in treatment group | Number in comparison group | Treatment group frequency | Comparison group frequency | Estimated difference (% points) | Significant difference? | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | 34,330 | 1.61 | 2.39 | -1.47 to -0.11 | Yes | 0.02 |

9. Profile of the treatment group

Individuals are referred from a variety of sources including the Probation Service, the Department for Work and Pensions and self-referral.

The main criteria for referral is that each individual has a criminal record irrespective of whether this resulted in a custodial sentence or a community based sentence.

| Participants included in analysis (154 offenders) | Participants not included in analysis (389 offenders with available data) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 100% | 90% |

| Female | 0% | 10% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 77% | 83% |

| Black | 10% | 10% |

| Asian | 8% | 6% |

| Other | 1% | 1% |

| Unknown | 4% | 2% |

| UK national | ||

| UK nationality | 91% | 89% |

| Foreign nationality | 6% | 4% |

| Unknown nationality | 3% | 6% |

| Index disposal | ||

| Community order | 16% | |

| Suspended sentence order | 15% | |

| Conditional discharge | 2% | |

| Fine | 4% | |

| Other | 1% | |

| Prison | 61% | |

| Caution | 2% |

Please note totals may not appear to equal the sum of the component parts due to rounding.

The individuals in the treatment group were aged 18 to 63 years at the beginning of their one-year period (average age 35).

Information on index offences for the 389 participants not included in the analysis is not available, as they could not be linked to a suitable sentence.

For 142 people, no personal information is available.

Information on individual risks and needs was available for 122 males in the overall treatment group (79%), recorded near to the time of their original conviction. This information is not complete for all 122 men across all risks considered for this analysis, but where it is known for specific risks, some key findings are shown below.

- 96% had some or significant problems with problem solving

- 93% had some or significant problems with their awareness of consequences

- 89% had some or significant problems with impulsivity

10. Matching the treatment and comparison groups

The analysis matched the treatment group to a comparison group. A large number of variables were identified and tested for inclusion in the regression models. The matching quality of each variable can be assessed with reference to the standardised differences in means between the matched treatment and comparison groups (see standardised differences annex). Over 95% of variables are categorised as green on JDL’s traffic light scale, indicating that the matching quality achieved on the observed variables was very good.

Further details of group characteristics and matching quality, including risks and needs recorded by the Offender Assessment System (OASys), can be found in the Excel annex accompanying this report.

This report is also supplemented by a general annex, which answers frequently asked questions about Justice Data Lab analyses and explains the caveats associated with them.

11. Additional information on the dataset

11.1 Index dates

The index date is the date at which the follow up period for measuring reoffending begins.

- For males with custodial sentences, the index date is the date they are released from custody.

- For males with a court order (such as a community sentence or a suspended sentence order), the index date is the date when an offender begins the court order.

- For males with non-custodial sentences such as a fine, the index date is the date when the offender received the sentence.

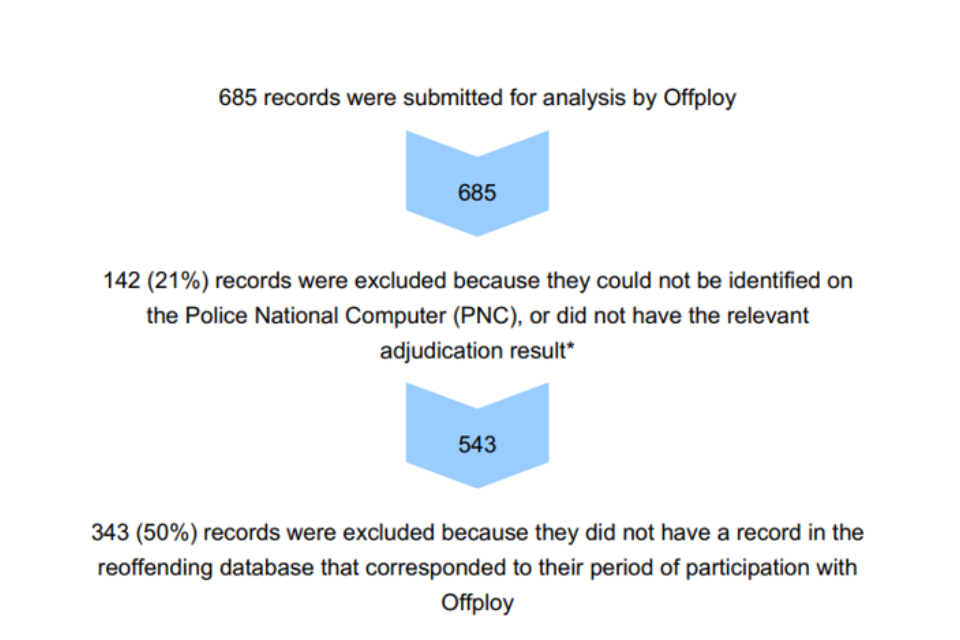

12. Participants excluded from the analysis

Some individuals have participated in the programme following their release from prison or after they have received a court order or non-custodial sentence. A maximum inclusion criterion of six months between the index date and intervention start date has been applied to these individuals to ensure the analysis captures any ‘treatment effects’. Any participants with intervention dates more than six months from the index date are therefore excluded from the analysis.

Individuals in the comparison group who have a Government Office Region (GOR) of Wales or the South West have been excluded from this analysis. This is because the treatment group did not include any individuals who had a GOR of Wales or the South West.

13. Other considerations

Part of the cohort within this publication overlaps with the COVID-19 pandemic including lockdowns and operational restrictions. It will therefore be affected by the continued recovery of the courts system. Particularly, continued delays in the processing of cases mean that increased numbers of reoffence convictions may fall outside of six-month waiting period and therefore not be counted in these statistics.

14. Numbers of people in the treatment and comparison groups

15. Further information

15.1 Official Statistics

Our statistical practice is regulated by the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR).

OSR sets the standards of trustworthiness, quality and value in the Code of Practice for Statistics that all producers of official statistics should adhere to.

You are welcome to contact us directly with any comments about how we meet these standards.

Alternatively, you can contact OSR by emailing regulation@statistics.gov.uk or via the OSR website.

15.2 Contact

Press enquiries should be directed to the Ministry of Justice press office.

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/ministry-of-justice/about/media-enquiries

Other enquiries about the analysis should be directed to:

15.3 Justice Data Lab team

E-mail: justice.datalab@justice.gov.uk

© Crown copyright 2024

Produced by the Ministry of Justice

Alternative formats are available on request from justice.datalab@justice.gov.uk

This document is released under the Open Government Licence