Public Health Outcomes Framework: commentary February 2021

Published 2 February 2021

Applies to England

New in this update

The latest update includes data for 46 indicators, of which 4 have new definitions:

-

B15a - Homelessness - households owed a duty under the Homelessness Reduction Act

-

B15c - Homelessness: households in temporary accommodation

-

C23 – Percentage of cancers diagnosed at stages 1 and 2

-

D06c – Population vaccination coverage – Shingles vaccination coverage (71 years)

This summary provides the main messages from indicators updated with data new to the public domain. None of these data cover the period since 31 March 2020 and therefore will not show the impact of the pandemic. For a complete list of indicators that have been updated please see Public Health Outcomes Framework: indicator updates

Summary of selected updated indicators

A02a Inequality in life expectancy

This PHOF release includes updated data on inequality in life expectancy for England, regions and local authorities. Inequality in life expectancy, by deprivation level, in the PHOF is estimated using a summary measure called the slope index of inequality (SII). The higher the value of the SII, the greater the inequality within an area.

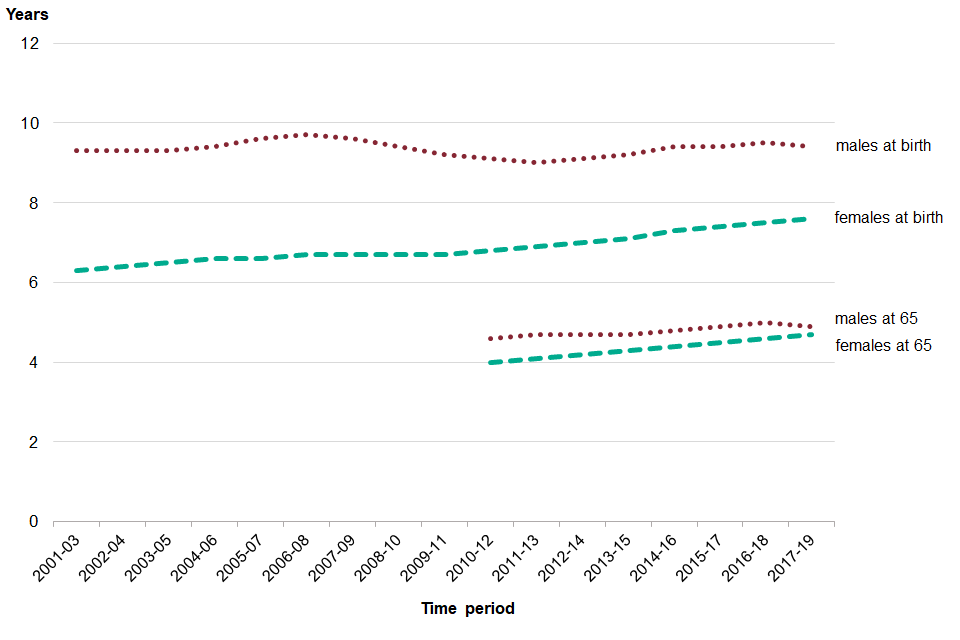

Inequality in life expectancy at birth was 9.4 years for males and 7.6 years for females at birth in 2017 to 2019. At age 65, the values are 4.9 years for males and 4.7 years for females (see figure 1). There were no significant changes in inequality compared with the previous period. Inequality in life expectancy at birth within England has widened between 2010 to 2012 and 2017 to 2019. Provisional data for the first 6 months of 2020 is available within the Wider Impacts of Covid-19 on health (WICH) monitoring tool.

Figure 1: Trends in inequality in life expectancy at birth and 65 in males and females, England, year 2001 to 2003 to year 2017 2019

It is important to be aware that SII values should not be compared across different geographies. The SII for England takes account of the full range of deprivation and mortality across the whole country. This does not provide a suitable benchmark with which to compare local authority results, which include the range of deprivation and mortality within much smaller geographies.

B12a Hospital admissions for violence, including sexual violence

This indicator measures the number of emergency hospital admissions for violence, which accounts for a small proportion of total cases of violence as it only includes those severe enough to warrant admission to hospital. The PHOF includes two further indicators on violent crime based on police recorded crime data.

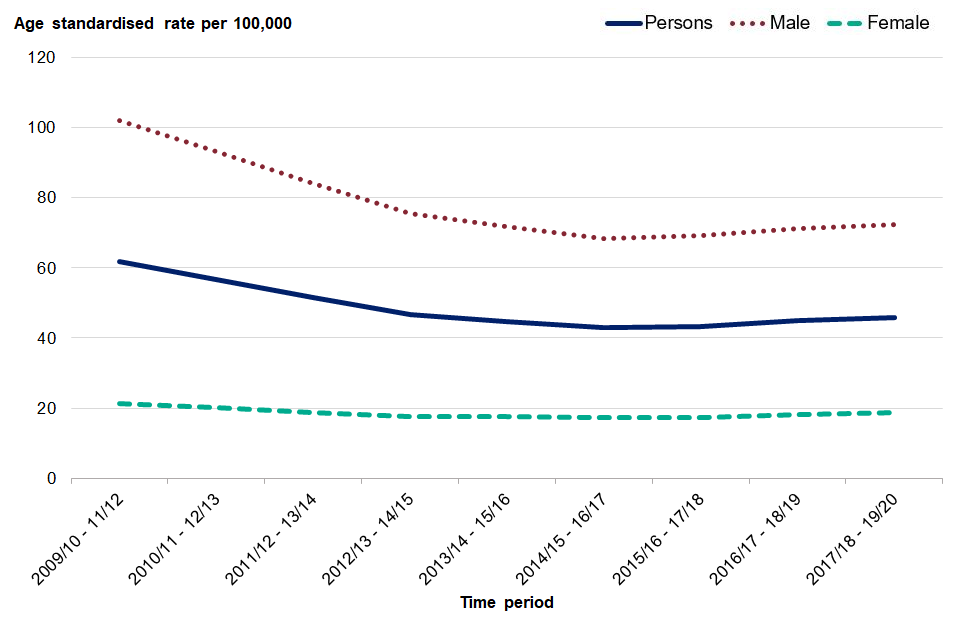

The admission rate in England for violence was 46 per 100,000 population in financial period 2017 to 2020. This equals 77,619 hospital admissions over the three-year period and is a significant increase on the previous period. The rate in England had been reducing year on year from 2009 to 2012 until 2014 to 2017. Admissions for males continue to be higher than females. In the latest period, there were 72 admissions per 100,000 population for males compared with 19 females per 100,000 population. (see figure 2).

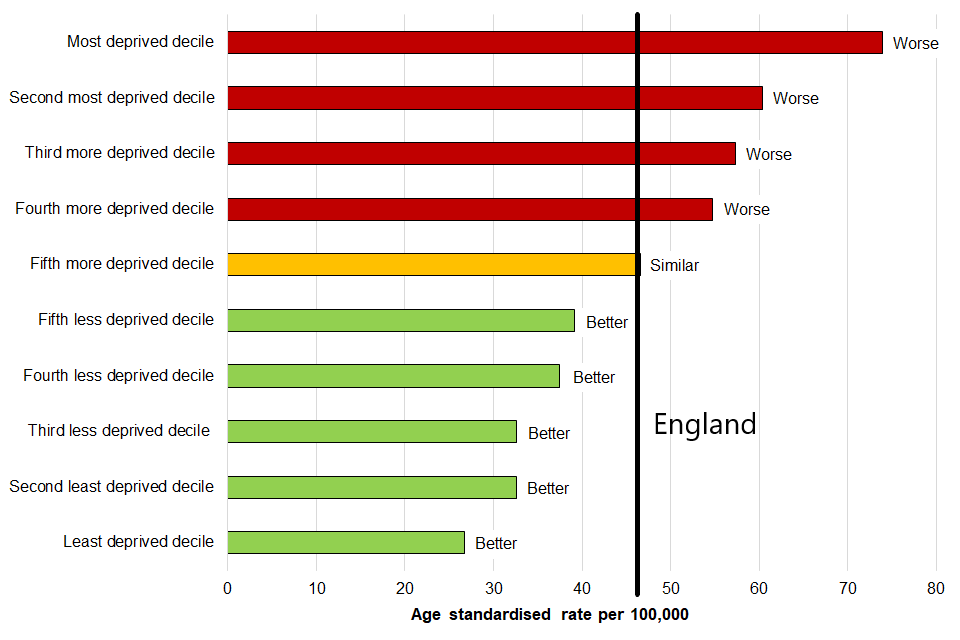

There is a clear deprivation gradient in admission rates with admissions almost 3 times higher in the most deprived areas than in in the least deprived areas (see figure 3).

Figure 2: Hospital admissions rate for violence, including sexual violence, England, 2009/10-2001/12 to 2017/18-2019/20

Figure 3: Hospital admissions for violence, including sexual violence by UTLA deprivation decile, compared with England, year 2017 to 2018 to year 2019 to 2020

C11a, b - Hospital admissions for unintentional and deliberate injuries in children and young people

Injuries are a leading cause of hospitalisation and represent a major cause of premature mortality for children and young people. They are also a source of long-term health issues.

The crude rates of admission for unintentional or deliberate injuries for children aged 0 to 4 and 0 to14 in England were 117 and 91 per 10,000 population respectively in the financial year 2019 to 2020. Both were significant decreases compared with the previous period. This continues the longer-term trend of a decrease in admission rates since 2013 to 2014.

For young people aged 15 to 24, the latest figure for England was 132 per 10,000 population in financial year 2019 to 2020.This was a significant decrease from the previous period. The longer-term trend has not changed significantly over the last 6 periods.

Figure 4: hospital admission rate for unintentional and deliberate injuries in children and young people, England, year 2010 to 2011 to year 2019 to 2020

C29 & E13 - Emergency hospital admissions for falls and hip fractures

Falls are the largest cause of emergency hospital admissions for older people, and significantly impact on long term outcomes. Hip fracture is a debilitating condition and has been demonstrated to have an immediate impact on an individual’s independence. Both these causes of hospital admission can lead to people moving from their own home to long-term nursing or residential care.

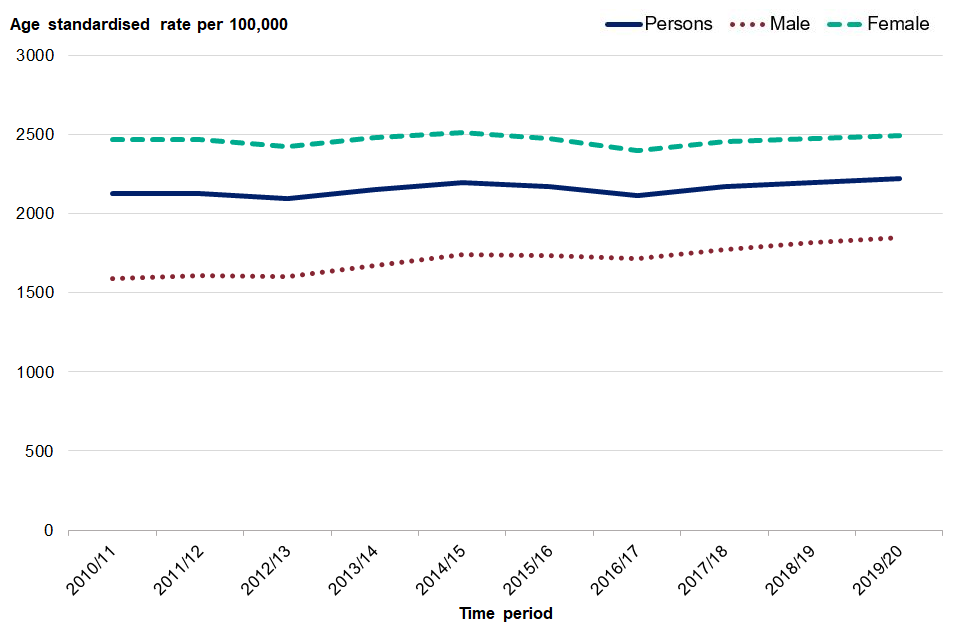

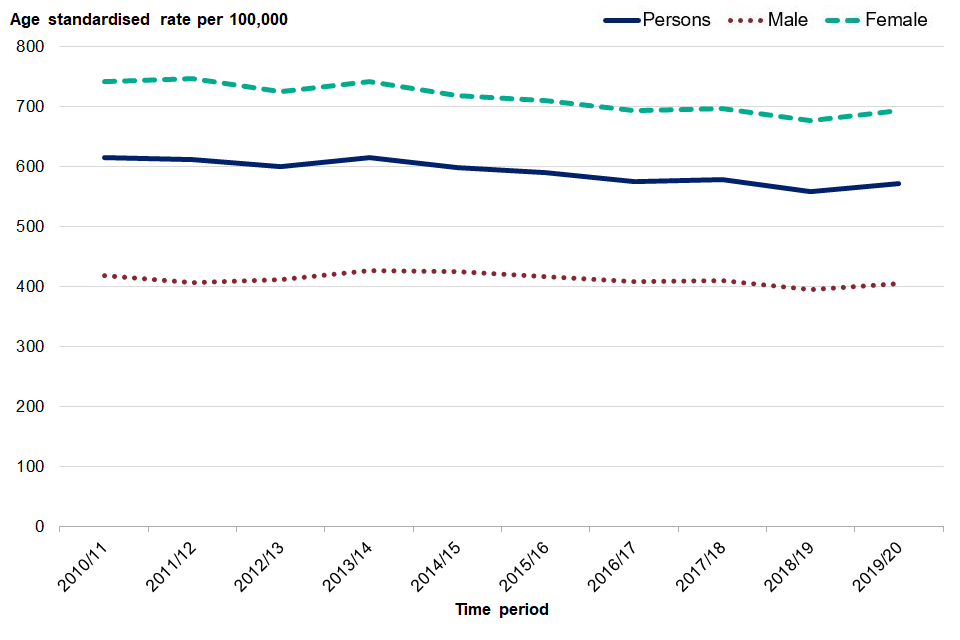

The rates of emergency hospital admission due to falls in the financial year 2019 to 2020 increased in 2 of the 3 age groups included in the PHOF (65 years and over and 80 years and over). For those aged 65 years and over the rate was 2,222 per 100,000 (234,793 hospital admissions).

Emergency admission rates for hip fractures for this period also increased in the same age groups. For those aged 65 years and over the rate was 572 per 100,000 (60,575 hospital admissions). The rate for females is consistently higher than that for males for both falls and hip fractures.

Figure 5: Emergency admission rate for falls in males, females and persons aged 65 years and over, England, 2010 to 2011 to year 2019 to 2020

Figure 6: Emergency admission rate for hip fractures in males, females and persons aged 65 years and over, England, year 2010 to 2011 to year 2019 to 2020

Background and further information

The Public Health Outcomes Framework sets out a high-level overview of public health outcomes, at national and local level, supported by a broad set of indicators. An interactive web tool makes the PHOF data available publicly. This allows local authorities to assess progress in comparison to national averages and their peers, and develop their work plans accordingly.

View the Public Health Outcomes Framework

Responsible statistician, product lead: Leigh Dowd For queries relating to this publication contact PHOF.Enquiries@phe.gov.uk

The next planned update is May 2021.