Adult substance misuse treatment statistics 2018 to 2019: report

Published 7 November 2019

1. Main findings

1.1 Trends in treatment numbers

There were 268,251 adults in contact with drug and alcohol services between April 2018 and March 2019, which was very similar to last year (268,390).

The number of adults entering treatment in 2018 to 2019 increased by 4% from the previous year (127,307 to 132,210). This is the first increase in the number of people coming to treatment since 2013 to 2014, possibly reflecting recent increases in the prevalence of illicit drug use.

1.2 Trends in substance use

The number of people in contact with treatment for opiates remained stable compared to last year, falling by 1% (141,189 to 139,845) with this group still making up the largest proportion in treatment (52%). Those in treatment for alcohol alone also remained stable (75,787 to 75,555). This follows large year-on-year declines from a peak of 91,651 in 2013 to 2014.

There were increases in the other 2 substance groups (2% increase in the non-opiate group and 3% in the non-opiate and alcohol group).

Following on from the last 2 years, there has been a continued rise in the number of adults starting treatment in the year with crack cocaine problems. This includes people who are using crack without opiates (4,535 compared to 4,301) and with opiates (24,363 to 22,411). While this increase is not as steep as previous years, the number of people starting treatment with crack problems has increased 32% since 2013 to 2014.

People starting treatment in the year saying they had problems with powder cocaine also increased in 2018 to 2019 (17,796 to 20,084). These increases in people coming to treatment with crack and cocaine problems are likely to be related to a surge in global cocaine production. This surge has lowered prices and increased purity. We have also seen changes in distribution and supply, such as ‘county lines’ drug dealing operations.

There was an increase in the number of adults entering treatment in 2018 to 2019 for problems with new psychoactive substances (NPS) (1,223 to 1,363, or 11%). This increase was largely driven by those taking NPS alongside opiates (they increased from 584 to 751, or 29%).

1.3 Housing and mental ill health

One-fifth (19%, or 24,565) of adults entering treatment last year said that they had a housing problem. This number varied by substance group, ranging from 1 in 10 (10%, or 5,208) starting treatment for problems with alcohol alone and almost a third (32%, or 13,405) starting treatment for problems with opiate use. The people starting treatment for problems with NPS had the highest proportion of housing need of any substance group (44%).

Over half (53%) of adults starting treatment said they had a mental health treatment need, ranging from 49% for people with opiate problems to 59% for people with non-opiate and alcohol problems.

1.4 Treatment exits and deaths

There were 118,995 people that exited the drug and alcohol treatment system in 2018 to 2019. Just under half (48%) left having successfully completed their treatment, free from dependence. This was the same level as the previous year.

The total number of people who died while in contact with treatment services in 2018 to 2019 was 2,889 (1.1% of all adults in treatment). This is an increase from the previous year (2,660, or 1% of all adults in treatment).

We saw increases in deaths for people in treatment across all substance groups, but the overall increase was driven by those in treatment for problems with opiates (1,712 to 1,897, or 1.4% of adults in treatment for opiate use).

Drug use is a significant cause of premature death in England, as the Office for National Statistics data has shown. In England, the number of deaths from drug misuse registered in 2018 increased by 16% to 2,670. This is at the highest level ever, with deaths of middle-aged heroin users being one of the main causes of the increase in drug poisonings. There was also a large increase in deaths involving powder cocaine or crack.

2. People in treatment: substance, sex, age

2.1 Overview

The National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) statistics report presents information on adults (aged 18 and over) who were receiving help in England for problems with drugs and alcohol in the period 2018 to 2019.

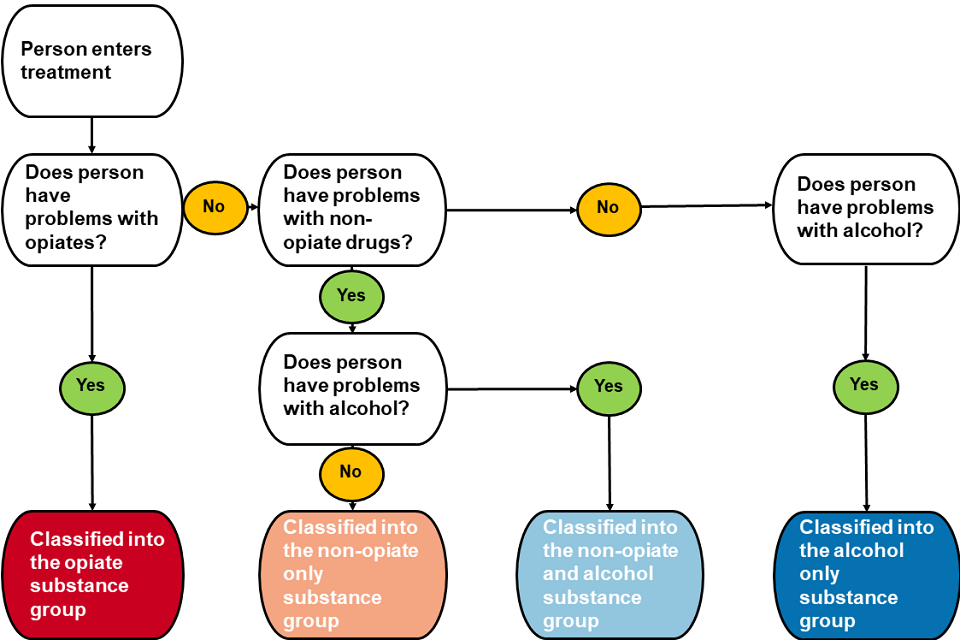

Many people experience difficulties with and receive treatment for both substances. While they often share many similarities, they also have clear differences, so this report divides people in treatment into the 4 substance groups:

- opiate: people who are dependent on or have problems with opiates, mainly heroin

- non-opiate: people who have problems with non-opiate drugs only, such as cannabis, crack and ecstasy

- non-opiate and alcohol: people who have problems with both non-opiate drugs and alcohol

- alcohol only: people who have problems with alcohol but do not have problems with any other substances

Figure 1: How people are classified into substance reporting group

2.2 Substance use, sex and age of people in treatment

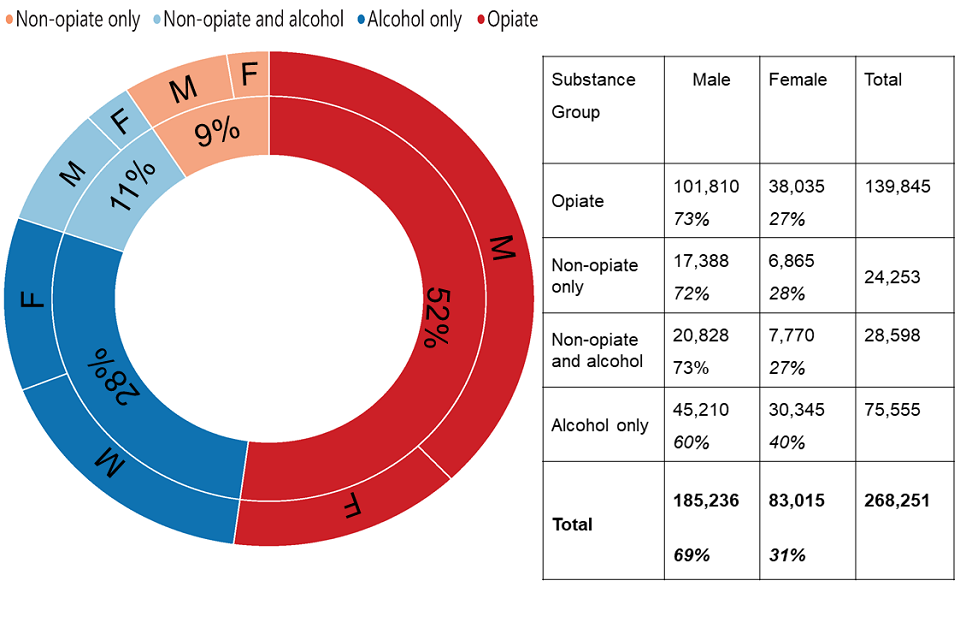

Figure 2: Breakdown of people in treatment by sex and substance group

There were 268,251 people in contact with drug and alcohol services between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2019.

Over half of all adults (52%) received treatment for problems with opiates. A further 20% had problems with other drugs and over a quarter (28%) had problems with alcohol. These proportions are similar to previous years and you can find more detailed information on trends in chapter 13.

Nearly three-quarters of people in treatment for opiates were male, which was similar to the non-opiate drugs groups. But 40% of people with alcohol only problems were female.

Over two-thirds of people in treatment were male, with men making up nearly three-quarters of those in treatment for opiates and non-opiates, compared to 60% for those in treatment for alcohol only.

2.3 Problem substances for people in treatment

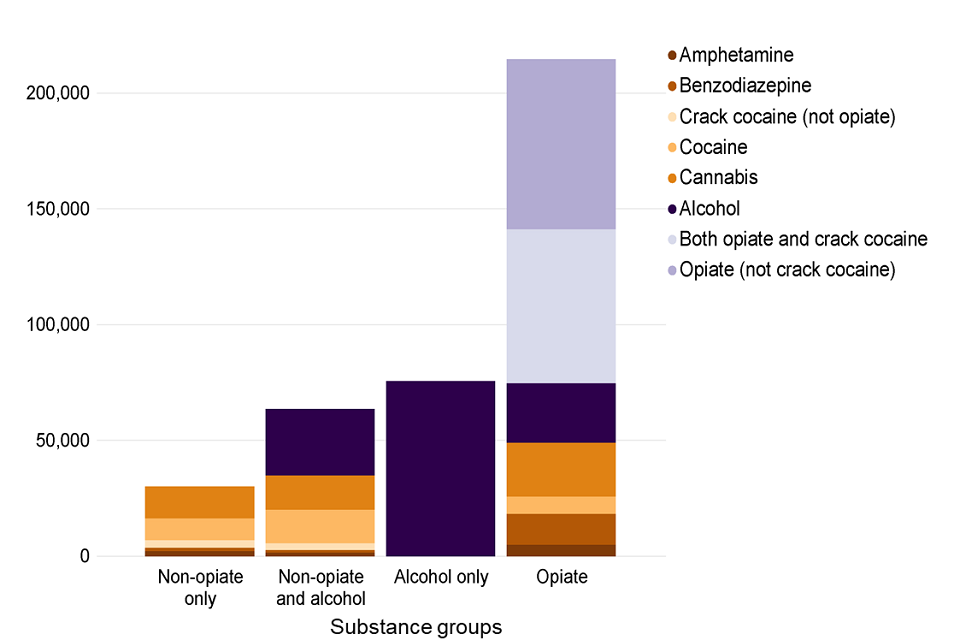

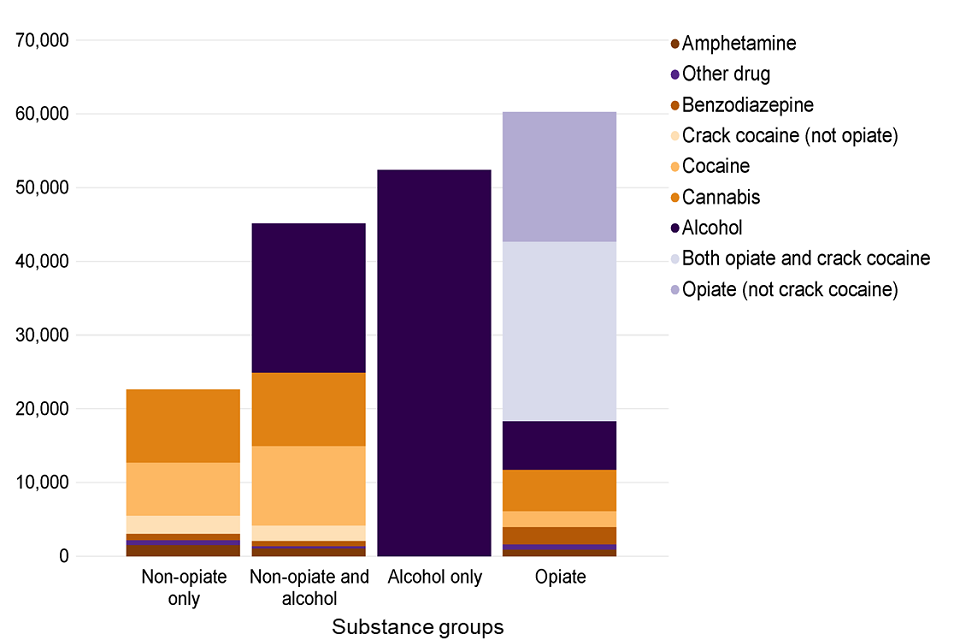

Figure 3: Substances by group for people in treatment (count of problem substances reported)

Up to 3 substances can be recorded at the start of treatment, so a person may be reported under several substance groups in the chart above.

In 2018 to 2019, 55% of people said they had a problem with either opiates or crack. And 48% of people said they had problems with alcohol, 19% said cannabis and 12% said cocaine. The next largest substance groups were benzodiazepines with 6% and amphetamines (excluding ecstasy) with 3%.

2.4 Age groups

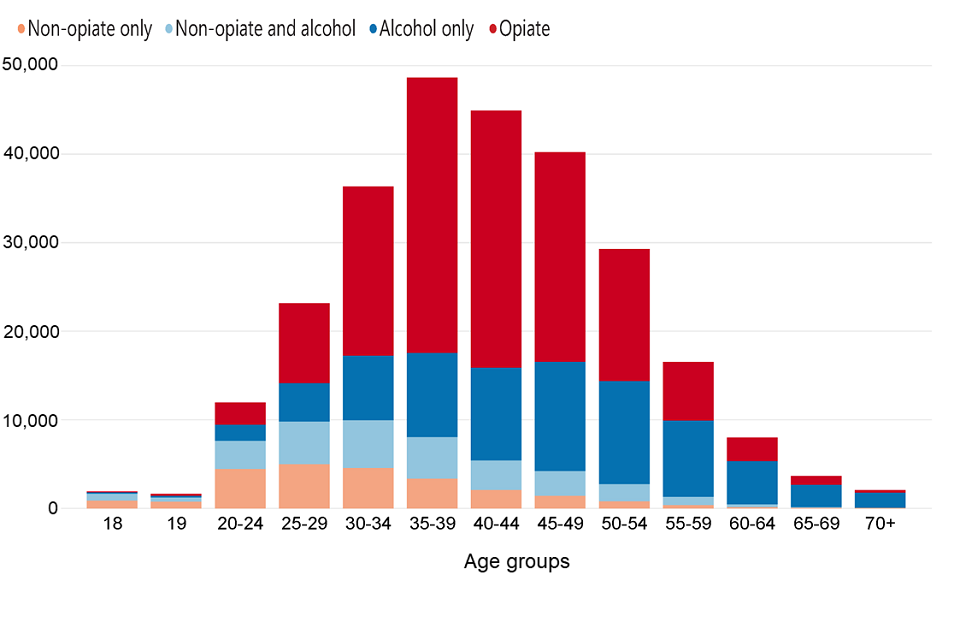

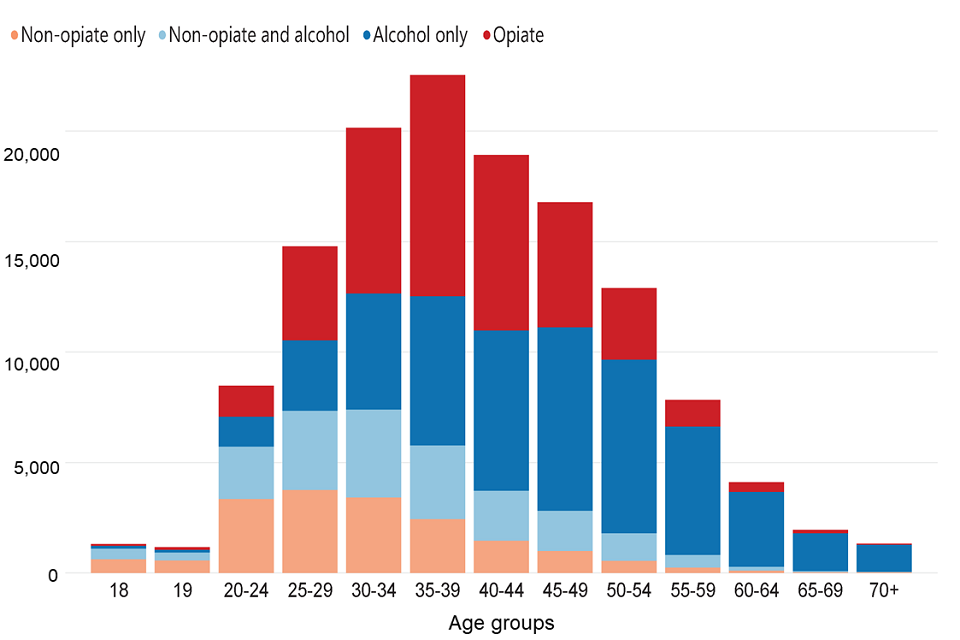

Figure 4: Age of people in treatment

The age of people in treatment has continued the trend from previous years showing an increase in older age groups. More than half of the people in treatment were over 40 years old (54%), with less than 10% of people in treatment for opiates or alcohol only were under 30 (8% for opiates and 9% for alcohol only).

The median age of people in treatment for the substance groups was very different with the median age of the alcohol only group being 16 years older (46) than for non-opiates only (30). People in treatment for opiates had a median age of 41. A detailed breakdown of age statistics can be found in the accompanying data tables.

The distribution of ages of people in treatment (see figure 4) mirrors patterns seen in estimates of prevalence of drug and alcohol use. The latest estimates for 2016 to 2017 show a significant increase in those aged 35 and over who use opiates (130,628 in 2010 to 2011 and 175,452 in 2016 to 2017), reflecting an ageing group rather than new, older users of the drug.

A large proportion of opiate-users in treatment will have started using heroin in the epidemics of the 1980s and 1990s and are now over 40 years of age. In 2017 to 2018, 69% said they first used heroin before 2001 and only 9% first used heroin since 2011.

People who use other substances other than opiates or alcohol tended to be younger. You can find more information about this in the Home Office’s Crime Survey for England and Wales.

3. Meeting the needs of people who are dependent on alcohol and drugs

The NDTMS treatment figures show us how many people are in treatment, but we can compare this to prevalence data to get an idea of how people’s needs are being met nationally and in each local area.

The main prevalence data we use in this context are:

- estimates of opiate and crack use, produced by Liverpool John Moores’ University for Public Health England (PHE)

- estimates of alcohol dependence produced by Sheffield University for PHE

3.1 Opiate and crack use

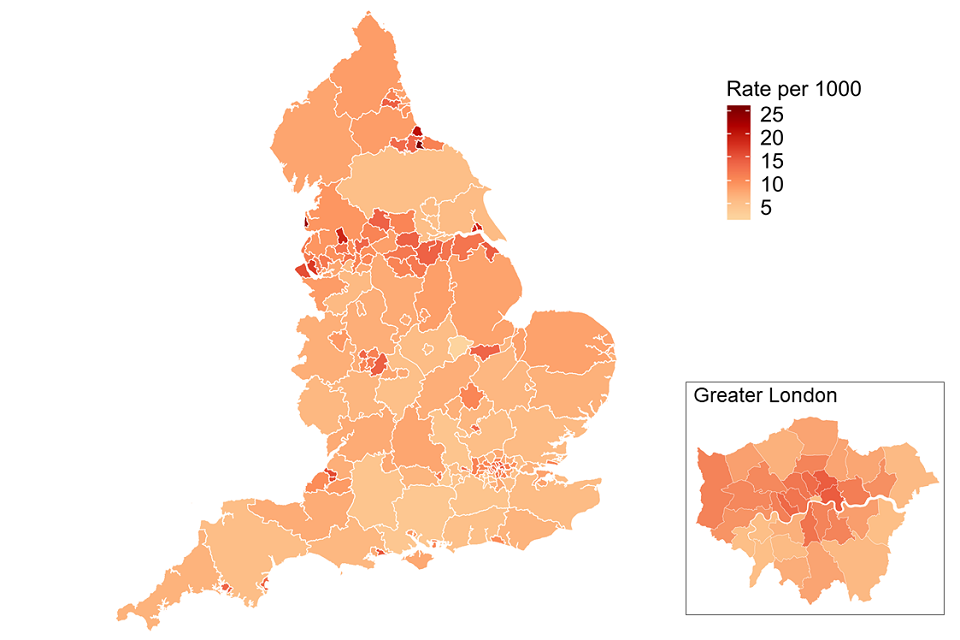

Figure 5: Map of opiate and crack use prevalence in 2016 to 2017 by local authority

The opiate and crack use prevalence estimates show that in 2016 to 2017 (the most recent data available) there were 313,971 in England aged 15 to 64 who use one or both drugs, made up of 261,294 opiate users and 180,748 crack cocaine users.

Nearly two-thirds of these people are between 35 and 64 years old. The proportion of opiate users who are not in treatment has continued to rise from 40.8% in 2014 to 2015 to 46.4% in 2018 to 2019. The proportion of crack users who are not in treatment is 40.3%.

Levels of opiate and crack use vary across England, ranging from 2 people per thousand of the population to 26 people per thousand, with many of the highest prevalence rates in the north of England.

Opiate and crack use is also strongly linked to deprivation. We saw 58% of people in treatment for crack and 57% of those in treatment for opiates living in areas ranked in the 30% most deprived areas.

PHE has published the latest opiate and crack prevalence estimates for each local authority in England.

You can also see how local areas compare on the numbers of opiate users and dependent drinkers who are not in treatment in the Public Health Dashboard.

3.2 Alcohol dependence

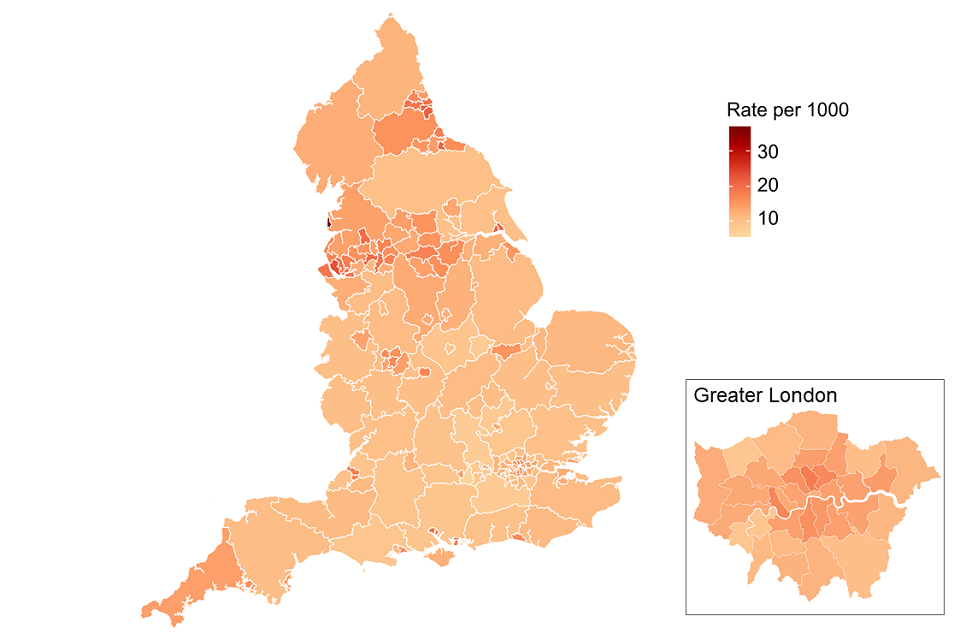

Figure 6: Map of alcohol dependence prevalence in 2017 to 2018 by local authority

There were an estimated 586,797 adults with alcohol dependency and in need of specialist treatment in 2017 to 2018 (the most recent figures available). These estimates have remained relatively stable over the last 5 years.

There were 104,153 individuals in treatment for alcohol in 2018 to 2019 (the total of alcohol only plus the non-opiate and alcohol groups[footnote 1]), so there was an estimated 82% of adults in need of specialist treatment for alcohol who were not receiving it.

Similar to the opiate and crack prevalence rates, the higher prevalence rates are concentrated in the north of England.

Nearly half of alcohol only clients in treatment (47%) were living in areas ranked in the 30% most deprived areas.

PHE has published the latest prevalence estimates for alcohol dependence for each local authority in England.

You can also see how local areas compare on the numbers of dependent drinkers who are not in treatment on the Public Health Dashboard.

4. People starting treatment: substances, age and referral source

4.1 Substances of people starting treatment

Figure 7: Substances by group for people starting treatment in 2018 to 2019 (count of problem substances reported)

In 2018 to 2019, 132,210 people started treatment for drug and alcohol problems. This is where a person started a new treatment journey, which might also include returning to treatment.

Of the people starting treatment:

- 35% were new to the treatment system

- 60% said they had a problem with alcohol

- 32% said they had a problem with opiates

- 22% said they had a problem with crack cocaine

- 19% said they had a problem with cannabis

- 15% said they had a problem with cocaine

Also, of the people who said they had a problem with alcohol, 66% (52,393) said it was their only problem substance.

There was a rise (11%) in the number of people starting treatment saying they had a problem with NPS from 1,223 to 1,363. This increase was largely driven by those using NPS alongside opiates (from 584 to 751 people) which is 2% of those with opiate problems. For more detail on the breakdown of NPS by substance group please see the accompanying data tables.

4.2 Age of people starting treatment

Figure 8: People starting treatment by age

Nearly half of people new to treatment (48%) were 40 years and over. In the older age groups, many of these people said they had problems with alcohol only. This rose to over 80% for those aged 55 years and over.

Forty percent of people in the non-opiate and non-opiate and alcohol groups were under 30 years old.

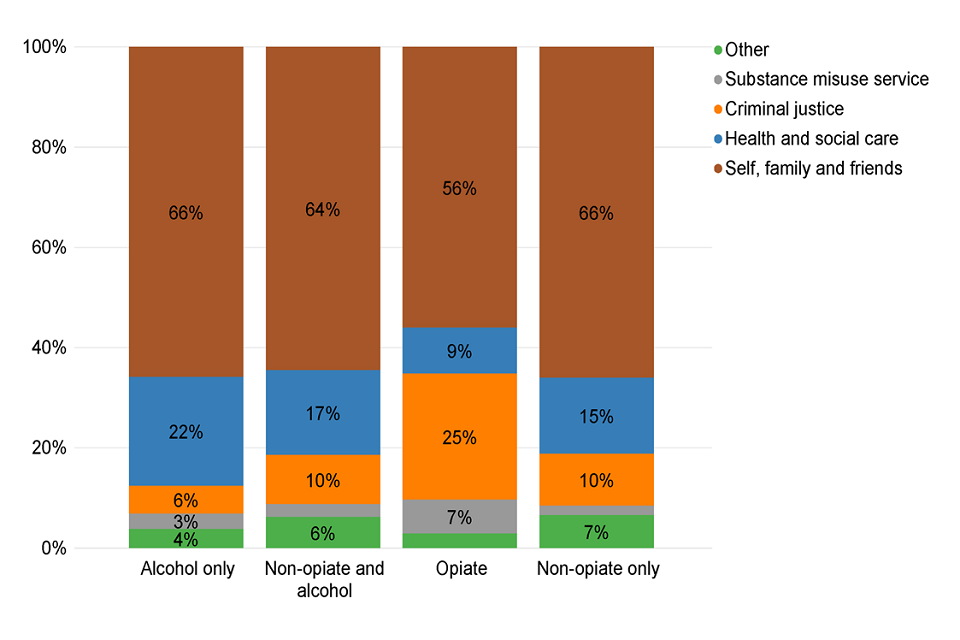

4.3 Referral sources

Figure 9: Referral sources for people starting treatment in 2018 to 2019

Of the people starting treatment in 2018 to 2019, 62% self-referred (which may be following advice from a healthcare professional) or were referred by family and friends.

Fifteen percent of referrals were from healthcare (including GPs which accounted for 8%), though this was higher for the alcohol only group, and 3% of all referrals were from hospitals. Only 1% of referrals came from social services.

Thirteen percent of referrals came from the criminal justice system. But there was a big difference between substance groups, with 25% of opiate referrals coming from the criminal justice system compared to just 6% for those with only alcohol problems. Prison referrals accounted for 6% of all referrals. You can see a further breakdown of these groups in the accompanying data tables.

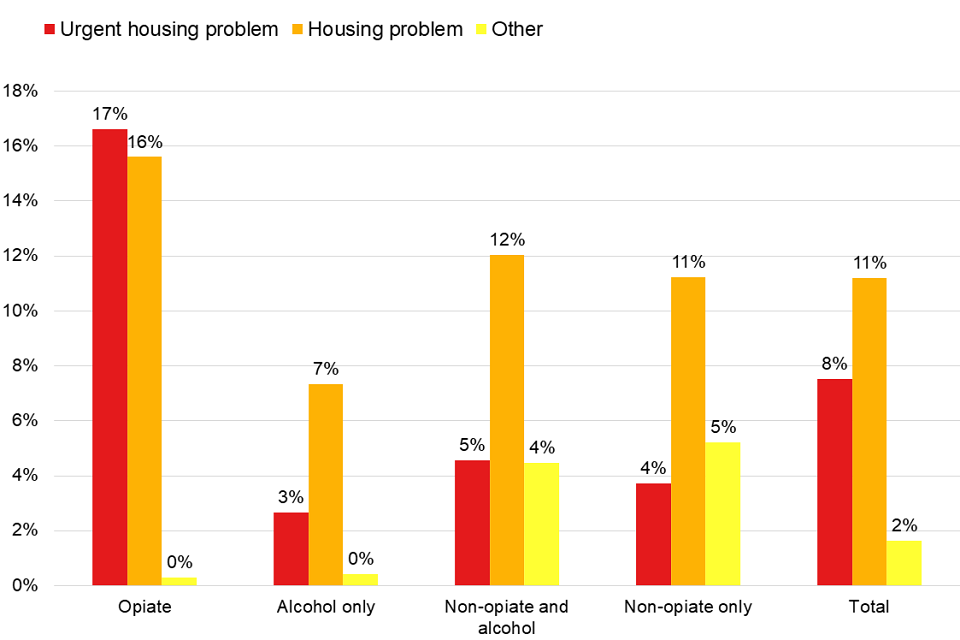

5. Housing

Figure 10: Housing need for people starting treatment in 2018 to 2019

Nearly one-fifth of people (19%) starting treatment said they had a housing problem and 8% had an urgent problem. For people with opiate problems, the proportion with an urgent housing problem rose to 17%.

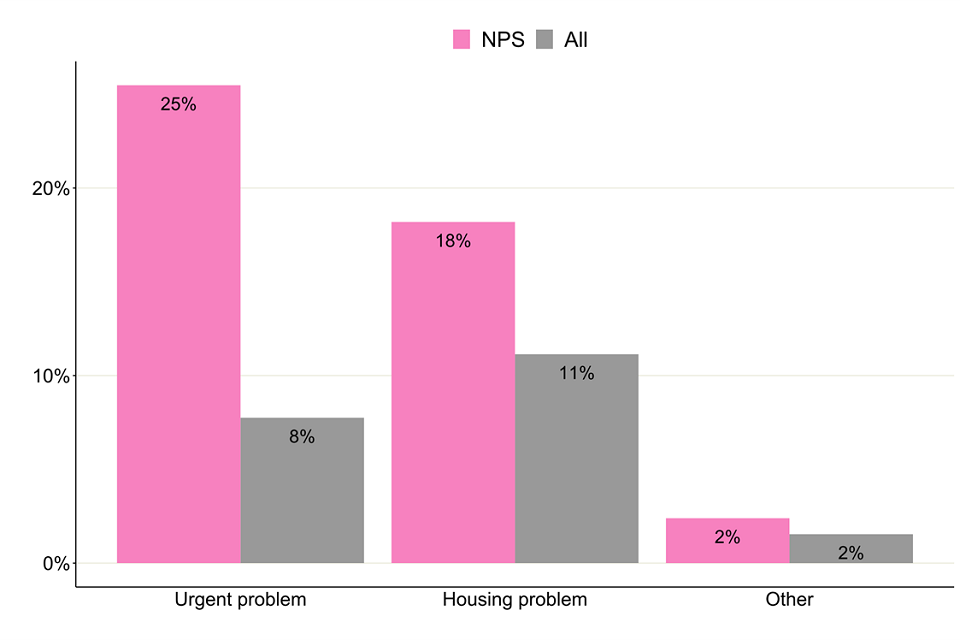

The people in treatment with NPS problems had the highest proportion of housing need, with 44% saying they had a housing problem (urgent or otherwise) when starting treatment.

Figure 11: Housing need for people with problems with new psychoactive substances starting treatment in 2018 to 2019

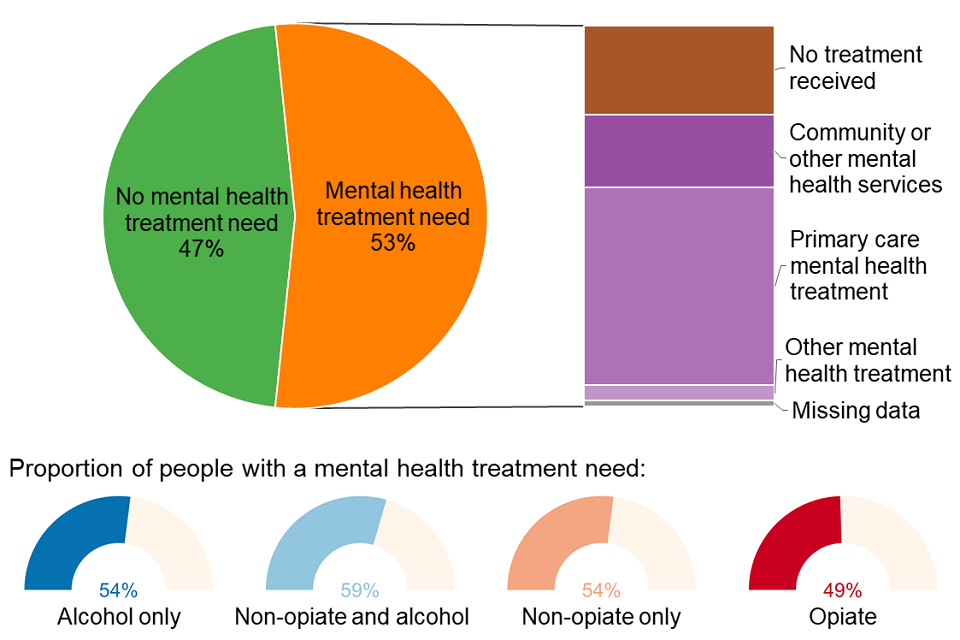

6. Mental health

Figure 12: Mental health need and treatment received for people starting treatment in 2018 to 2019

Fifty-three percent of people starting treatment said they had a mental health need. This ranged from 49% for people in treatment for opiates to 59% for people with non-opiate and alcohol problems.

Twenty-four percent of people starting drug and alcohol treatment who had a mental health need were not receiving any treatment to meet this need. Of those receiving mental health treatment, over half received it in a primary care setting, such as a GP surgery.

7. Injecting status

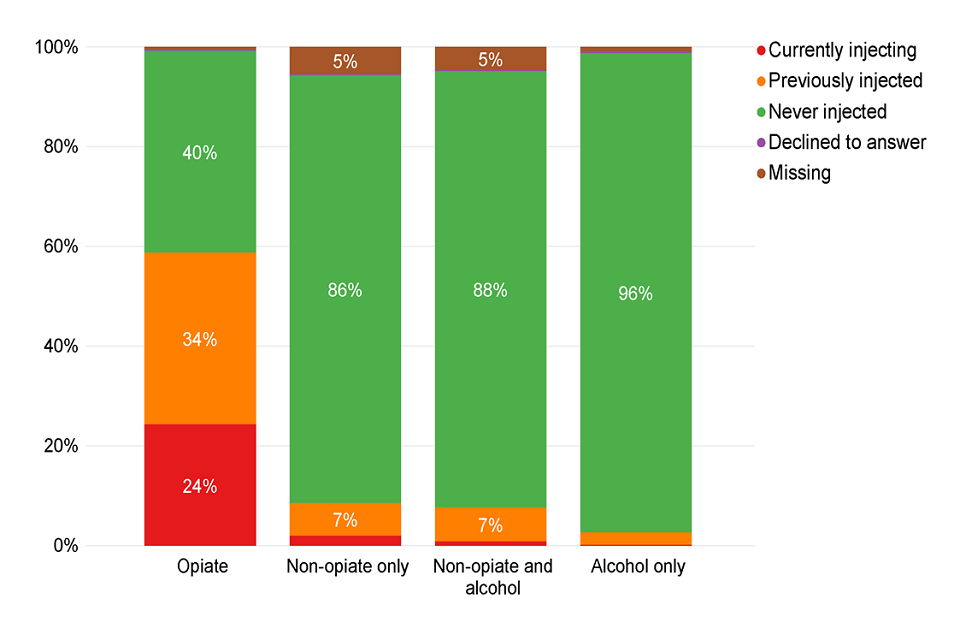

Figure 13: Injecting status of people starting treatment in 2018 to 2019

Twenty-two percent of all people starting treatment were currently injecting or previously had injected drugs. But for people with opiate problems, this rose to 59% with 24% currently injecting. Only 3% of people with alcohol only problems had ever injected.

8. Parental status and safeguarding children

8.1 Parental status

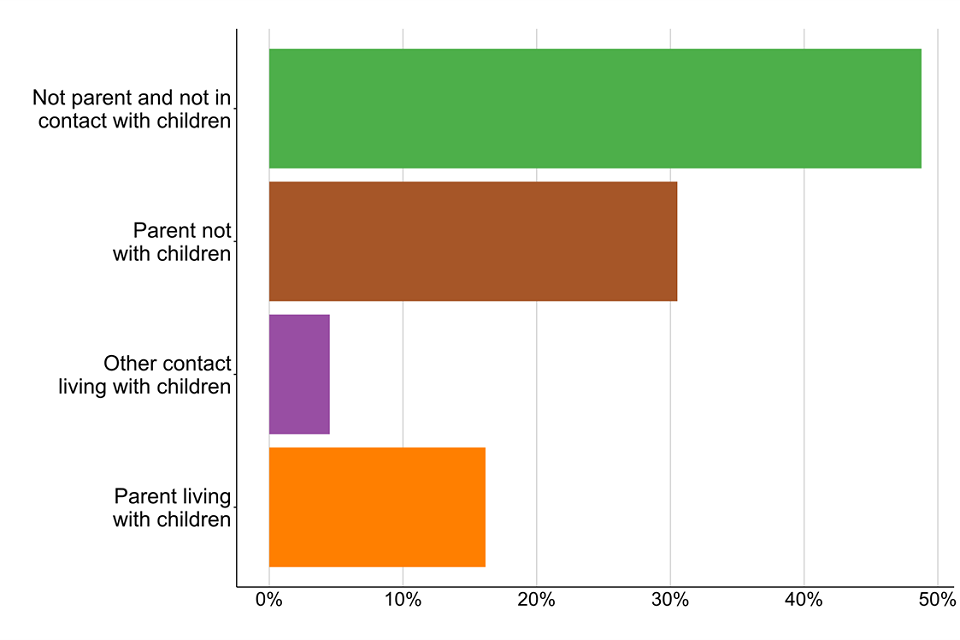

Figure 14: Parental status of people starting treatment in 2018 to 2019

In 2018 to 2019, 21% of people starting treatment were living with children, either their own or someone else’s. And 31% were parents who were not living with their children. This was highest among women in treatment for opiates, where 44% are parents who are not living with their children.

Fifty-eight percent of females reported either living with a child, or being a parent when they started treatment, compared to 48% of males.

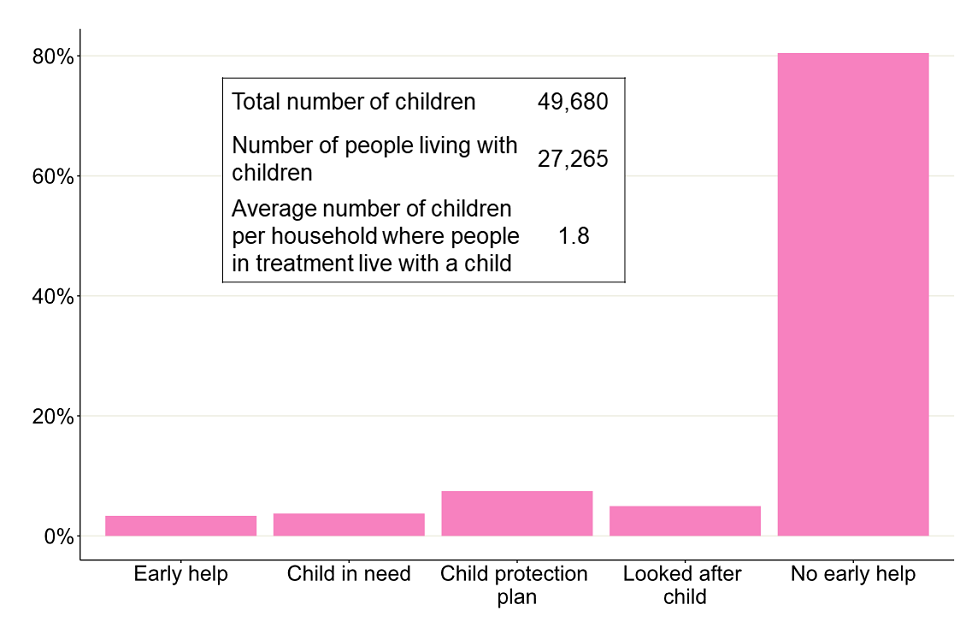

Figure 15: Children receiving early help or in contact with children's social care

Eighty percent of the children of people starting treatment were receiving no early help. We also saw that 7% had a child protection plan, but this figure rose to 15% in the non-opiate group.

9. Smoking

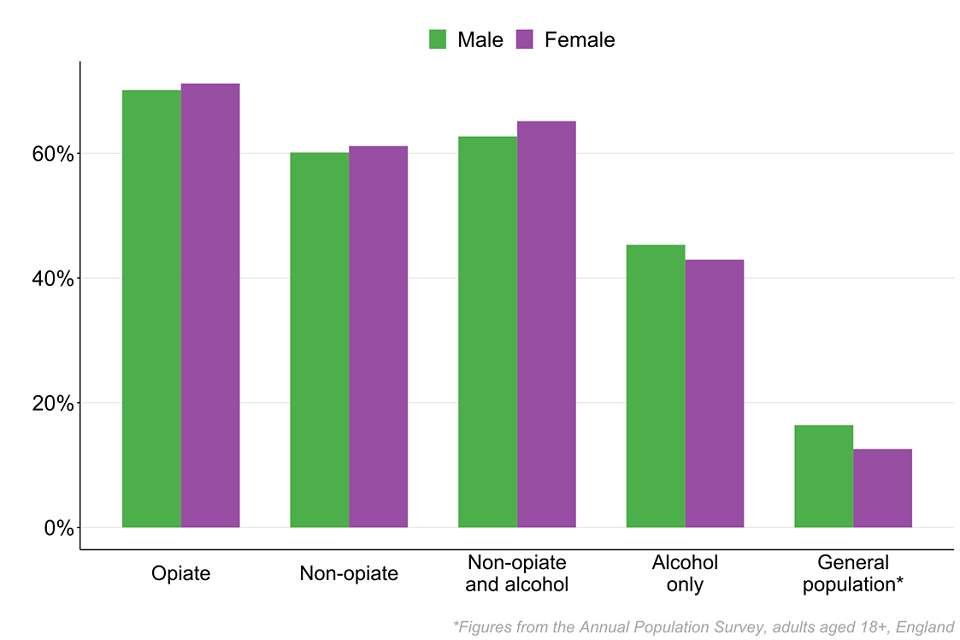

Figure 16: Smoking prevalence at the start of treatment

Nearly 49,000 people said they had smoked tobacco in the 28 days before starting treatment. This is based on information collected at the start of treatment and a 6-month review as part of PHE’s treatment outcomes profile (TOP).

Across all substance groups, males and females reported smoking at similar levels. And in all cases, the level of smoking was substantially higher than the smoking rate of the general population, 16.4% for males and 12.6% for females.

Despite the high levels of smoking, only 3% of people were recorded as having been offered referrals for smoking cessation interventions.

10. Treatment interventions

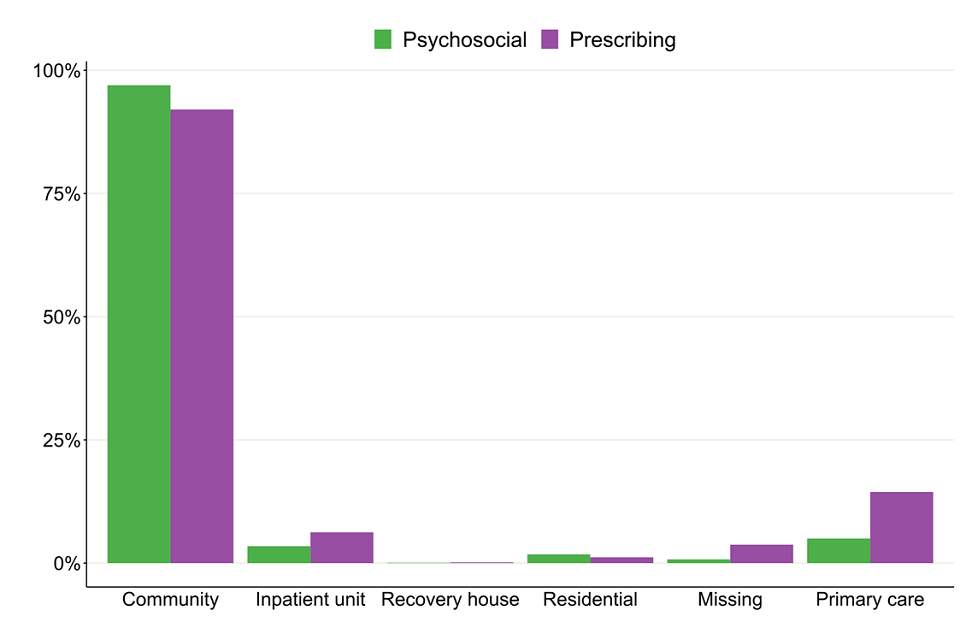

Figure 17: Breakdown of settings where peoples’ treatment took place

Almost all (99%) people in treatment received some form of structured treatment. You can find a definition of structured treatment in our business definitions guidance.

Of the people that did receive a structured treatment:

- 97% received a community-based treatment

- 9% received treatment in a primary care setting

- 4% received treatment in an inpatient setting

The number of people receiving treatment in inpatient and residential settings has continued to fall. There were 25,847 people receiving treatment in those settings in 2014 to 2015 compared to 16,757 people in 2018 to 2019.

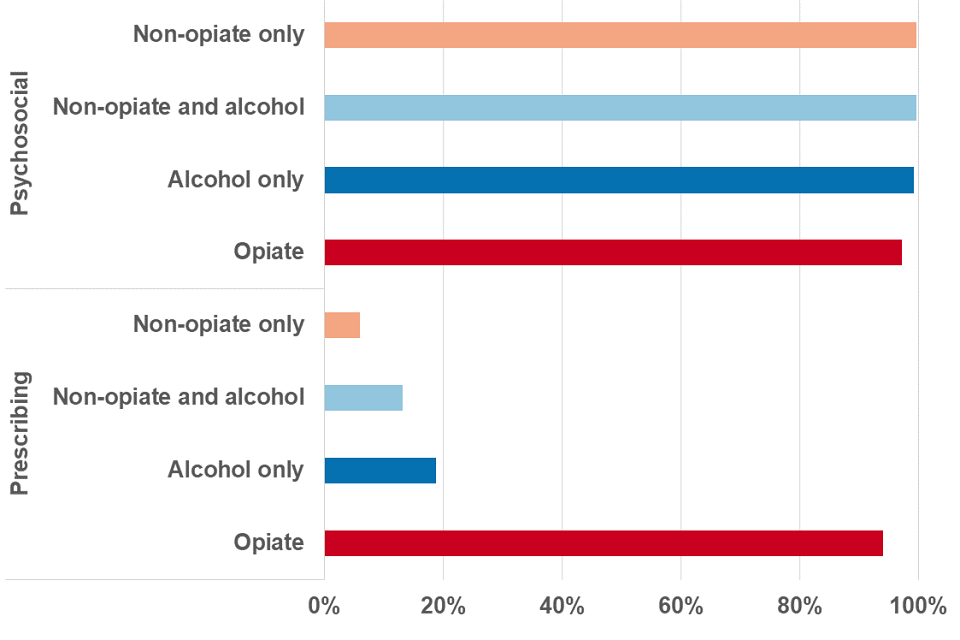

Figure 18: Breakdown of type of treatment that people received

Ninety-eight percent of people received a psychosocial intervention while 57% received at least one pharmacological intervention. For people with opiate problems, 94% received a pharmacological intervention, while only 6% of the non-opiate group received one.

Of the people starting treatment, 98% did so in 3 weeks or under.

11. Treatment outcomes

11.1 Treatment exits and successful completion of treatment

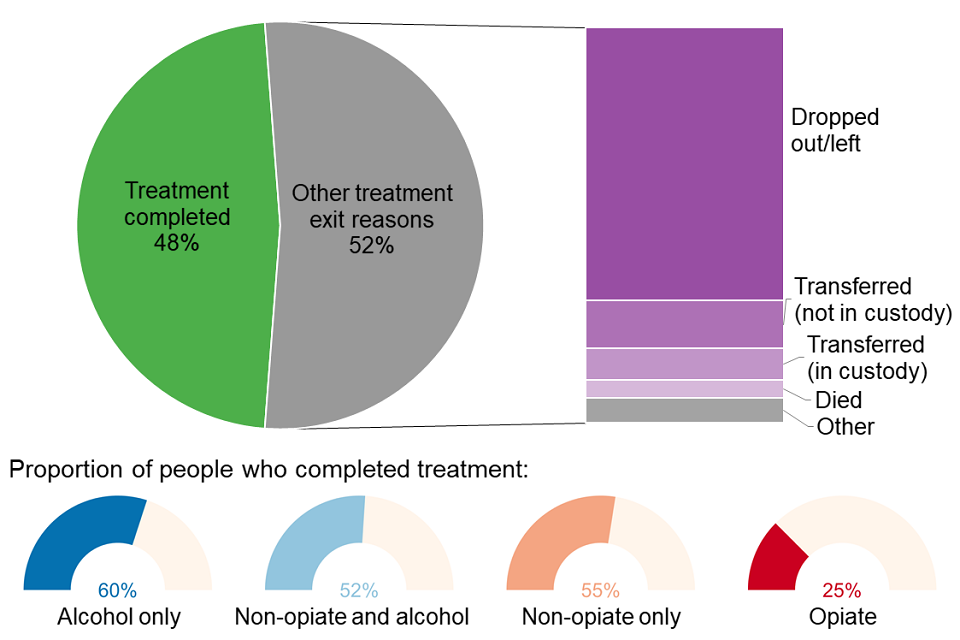

Figure 19: Breakdown of latest treatment exits in 2018 to 2019

A total of 118,995 people left drug and alcohol treatment in 2018 to 2019.

On average (mean), people who completed treatment did so within a year of starting treatment (318 days). The average time in treatment for people with opiate problems was nearly 3 years (1,067 days) and around 6 months for the other substance groups (157 days for non-opiates only, 190 days for non-opiate and alcohol and 193 days for alcohol only).

Almost half the people who left treatment (48%) were discharged as ‘treatment completed’. Opiate users had the lowest rate of successfully completing their treatment and being discharged as treatment completed (25%) and the alcohol only group had the highest rate (60%).

Around a third (36%) of people left treatment without completing it, while 13% left either due to unsuccessful transfers between services or the person declining further treatment.

11.2 Deaths in treatment

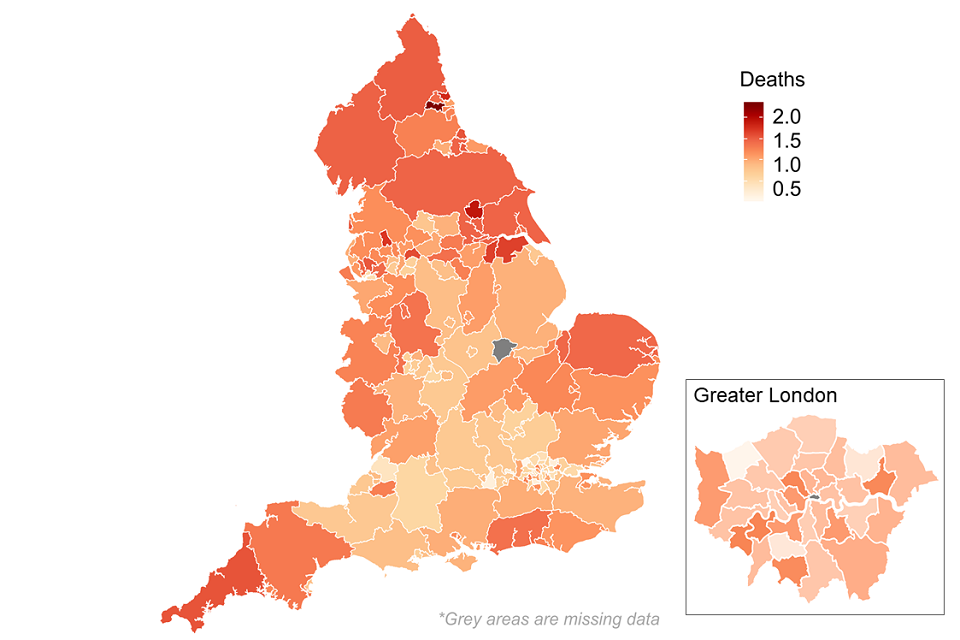

Figure 20: Map of deaths in drug treatment (mortality ratio for 2016 to 2017 and 2018 to 2019)

This map shows local authorities where deaths in drug treatment are higher or lower than expected (with a score of less than one being less deaths than would be expected). These figures are for people who die when they are in a treatment programme, not necessarily because their deaths are drug-related. It is calculated as an indirectly age-standardised ratio, and more detail can be found on the Public Health Dashboard.

There were 2,889 recorded deaths in treatment, which represented 1.1% of all people in treatment. People with opiate problems accounted for 65% of these deaths. Thirty-one percent of opiate deaths were from people living in the 10% most deprived areas of England, with the rate in these areas being 6 times greater than the least deprived.

Data from the Office for National Statistics shows that drug misuse poisonings have increased substantially (80%) over the last 7 years with those in the most deprived areas disproportionally affected.

In the main this has been driven by increases in heroin-related deaths, though other substances such as cocaine have seen notable recent increases. These are not necessarily people who have received drug treatment or are in treatment when they die.

Homeless deaths increased by 22% in 2018, driven by a 55% increase in drug poisonings among this population.

11.3 Self-reported outcomes: substance use

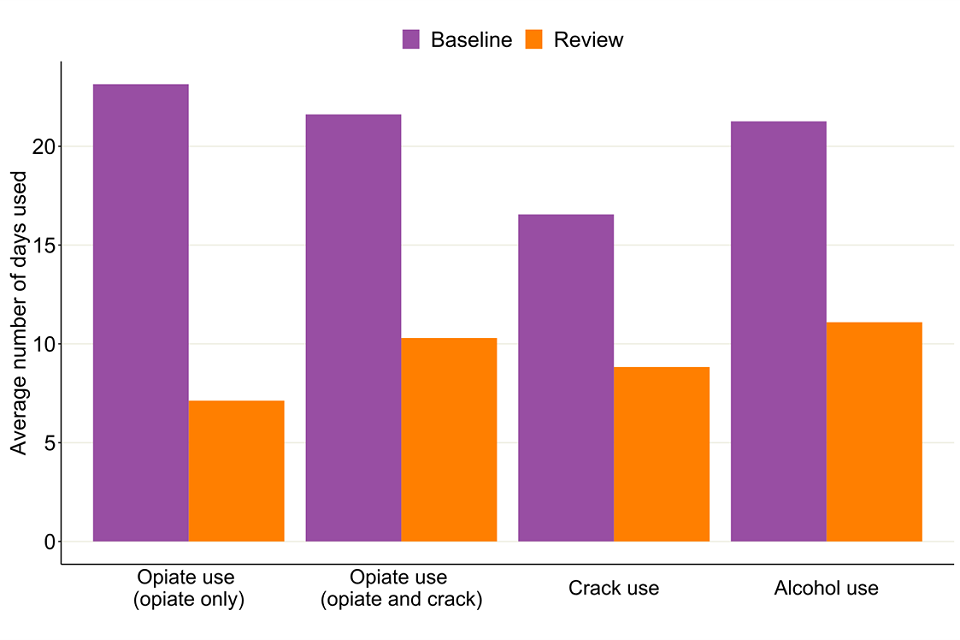

Figure 21: Change in self-reported number of days use between start of treatment and 6-month review

PHE collects information about the outcomes for users of drug and alcohol treatment services. This includes the TOP, which measures change and progress in important areas of their lives.

All together, people with opiate problems reported a fall in the average number of days using opiates, from 22.2 days in the last 28 days at the start of treatment to 9 days after 6 months of treatment.

The alcohol only group reported a fall in the number of days that they used alcohol, from 21.3 days to 11.1 days in the last 28 days before their 6-month review.

12. Self-reported outcomes: injecting, employment and education

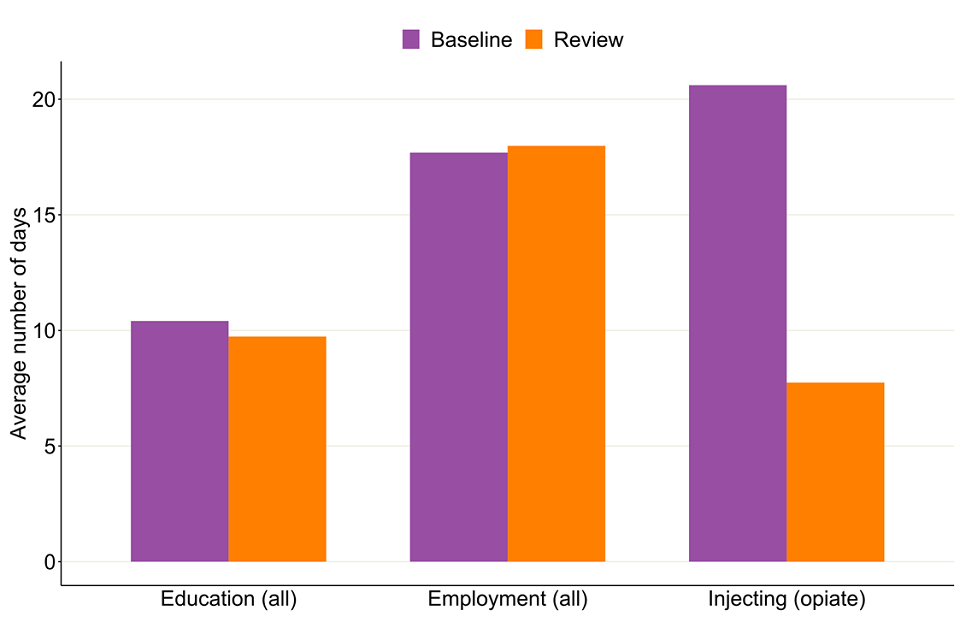

Figure 22: Change in self-reported injecting, employment and education between start of treatment and 6-month review

People in treatment reported an increase in the average amount of days they were in employment in the last 28 days, from 17.7 days before starting treatment to 18 days at their 6-month review.

The number of days of injecting by people with opiate problems dropped from 20.6 days to 7.7 days each month.

13. Trends over time

13.1 Numbers in treatment

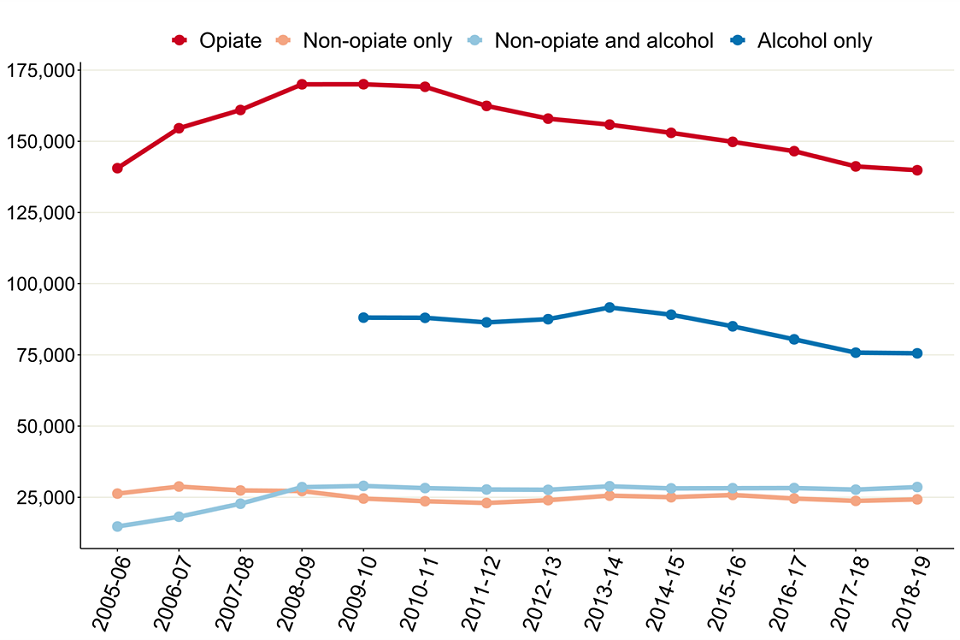

Figure 23: Trends in numbers in treatment by substance group from 2005 to 2006

The number of people in treatment has remained stable since last year with 268,251 people in treatment compared to 268,390 in 2017 to 2018. This is the first year numbers in treatment have remained stable since a decline from 2013 to 2014 onwards. Most of this decline was due to falls in the number of people receiving treatment for opiates or alcohol only.

There have been slight increases in numbers in the non-opiate (2% increase) and non-opiate and alcohol (3%) groups while there has been a slight fall in the opiate group (down 1%).

Numbers for people in treatment who said they had a problem with alcohol only are only shown from 2009 to 2010 onwards as that is when we started collecting national alcohol treatment data.

These trends over time can be found on NDTMS.net using the ViewIt tool. You can choose to display either England or local authority level data, as well as split the data by substance, sex and age groups.

13.2 People leaving treatment

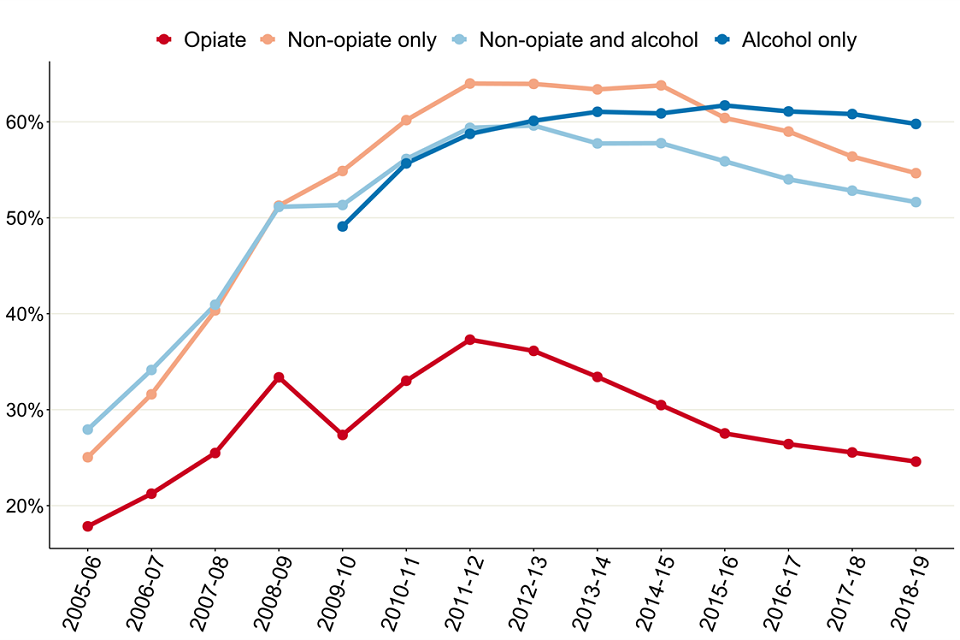

Figure 24: Trends in people completing treatment since 2005 to 2006

People leaving treatment free of dependence has continued to fall since a high point of 53% in 2013 to 2014. The fall in successful completion rates has been more marked for people with opiate problems, while people with alcohol only problems have just recently started to fall since a high of 62% in 2015 to 2016.

13.3 Opiate and crack use

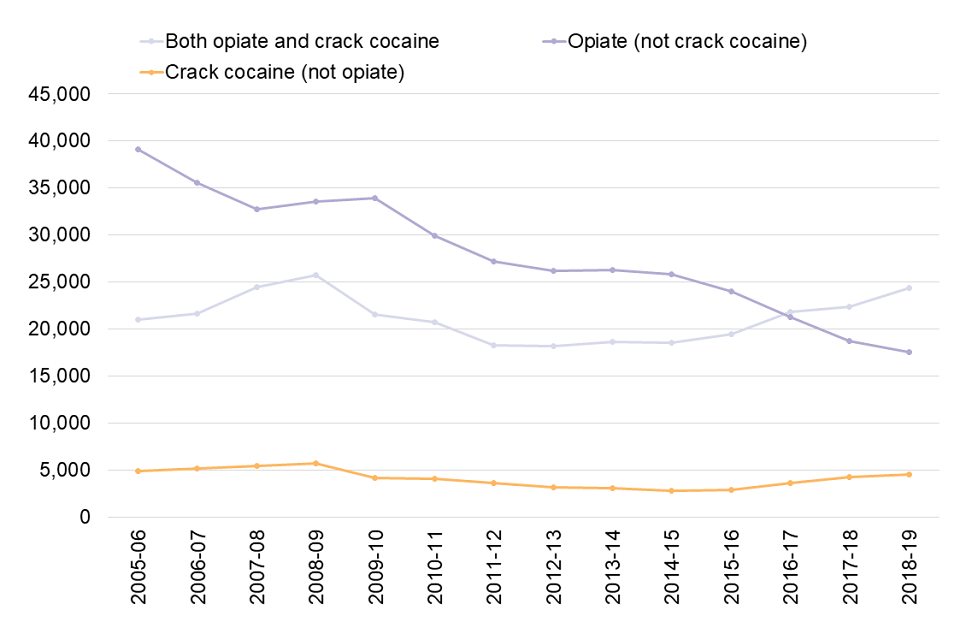

Figure 25: Trends of people in treatment with opiate and/or crack problems

We continue to see a rise in the number of people starting treatment saying they have a problem with crack cocaine. At the same time, we have seen a fall in the numbers of people who have opiate misuse problems but not crack problems.

The number of people coming to treatment with NPS problems increased in 2018 to 2019, from 1,223 to 1,363. This follows a decline over the last 2 years. The increase was in people who were also using opiates, which saw 751 people come to treatment this year compared to 584 in 2017 to 2018.

There were continued falls in people with ecstasy problems. We saw 924 people come to treatment compared to a high of 2,399 in 2007 to 2008.

There was a continued gradual rise in ketamine numbers, with 960 people coming to treatment compared to 426 in 2014 to 2015. Numbers of people with methamphetamine problems also rose to 386, compared to 131 in 2011 to 2012.

You can find more detailed data on the drugs people were having problems with in the accompanying data tables.

13.4 Deaths in treatment

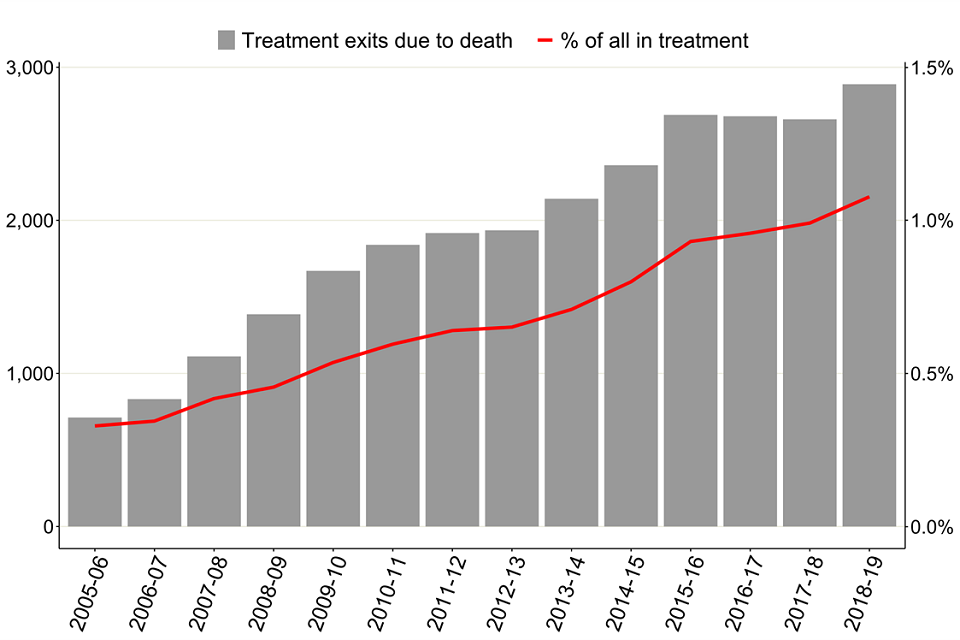

Figure 26: Trends in deaths of people in treatment

The number of deaths in treatment has continued to rise, including a large increase since 2017 to 2018, from 2,660 to 2,889 people this year. This was 1.1% of all people in treatment. This trend has increased rapidly in recent years, from 712 deaths in 2005 to 2006 to 2,889 deaths in 2018 to 2019.

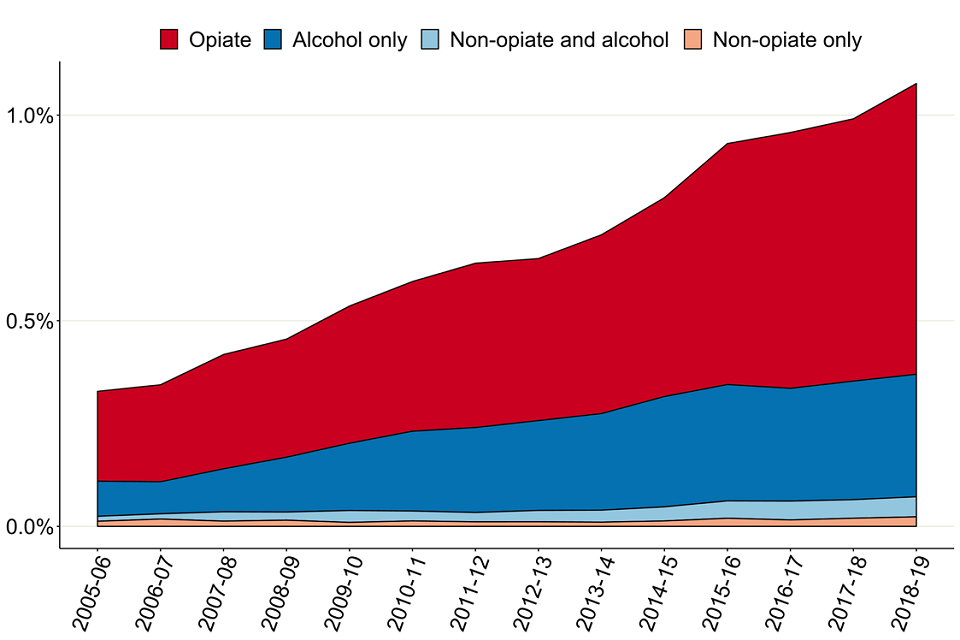

13.5 Deaths in treatment by substance

Figure 27: Percentages of deaths in treatment since 2005 to 2006

People having problems with opiates and alcohol only have the biggest increases in the number and rate of deaths. We have seen significant increases since 2011 to 2012, where the total number of deaths in these substance groups has gone up from 1,816 people to 2,696 people.

The percentage of deaths ranged from 0.3% for people with non-opiate only problems to 1.4% for those with opiate issues.

14. A 14-year analysis

14.1 People in treatment

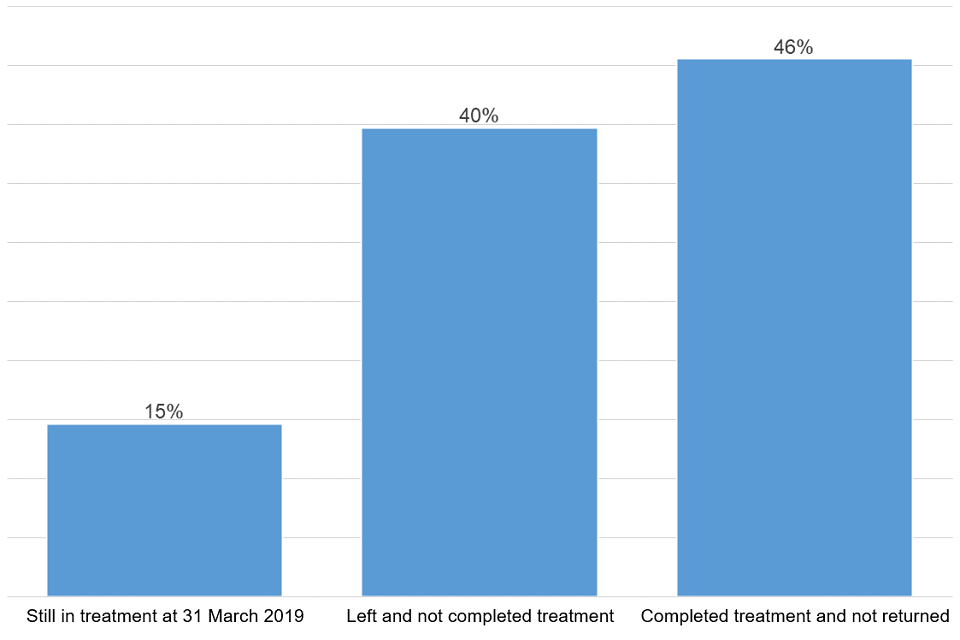

Figure 28: Last status of all people in treatment since 2005 to 2006

In the 14 years of treatment data starting from 2005 to 2006, we have seen a total of 966,040 different people in contact with drug and alcohol treatment services. By 31 March 2019:

- 141,667 (15%) were still engaged in treatment

- 383,954 (40%) had left and not completed their treatment and not returned

- 440,419 (45%) had completed their treatment and not returned

14.2 Treatment journeys

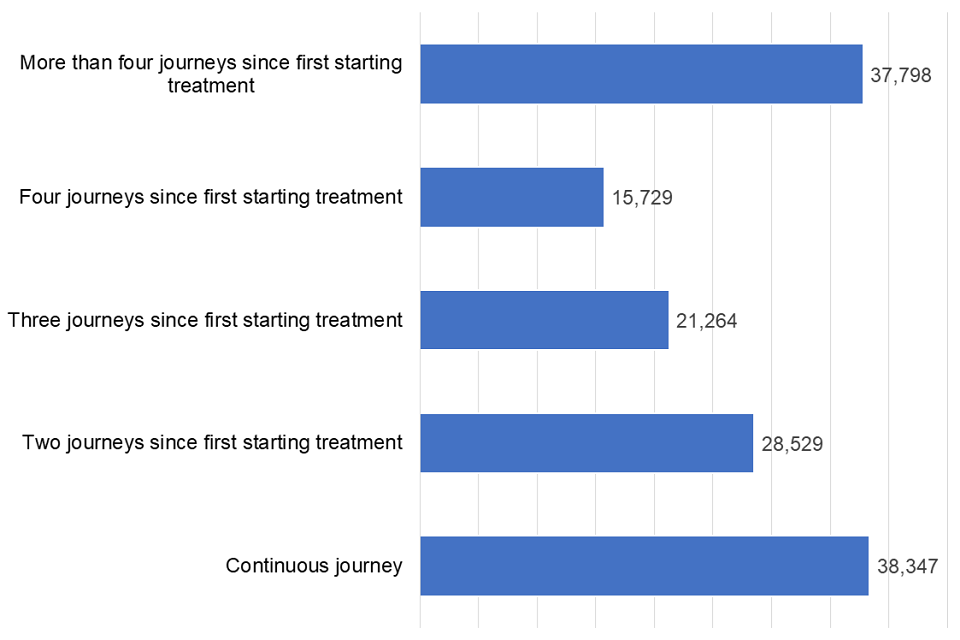

Figure 29: Number of previous journeys for people still in treatment at the end of 2018 to 2019

Of the people still in treatment at the end of March 2019, over a third (38%) have had 4 or more treatment journeys and over a quarter (27%) have been in treatment continuously.

You can find more information on the methodology of this analysis in the NDTMS annual statistics quality and methodology document.

15. Background and policy context

15.1 Background to the data

This report presents statistics on the availability and effectiveness of alcohol and drug treatment in England and the profile of people accessing this treatment.

The statistics in this publication come from analysis of the NDTMS. The NDTMS collects data from about 900 sites providing structured substance misuse interventions, covering every local authority in England. Treatment centres returning data include:

- community-based drug and alcohol services

- specialist outpatient services

- GP surgeries

- residential rehabilitation centres

- inpatient units

The data collected includes information on the demographics and personal circumstances of people receiving treatment, as well as details of the interventions delivered and their outcomes.

You can find more details on the methodology used in the report in the NDTMS annual statistics quality and methodology document.

15.2 Policy context

Alcohol and drug treatment in England is commissioned by local authorities using the public health grant. They are responsible for assessing local need for treatment and commissioning a range of services and interventions to meet that need.

The public health grant conditions make it clear that:

A local authority must, in using the grant: have regard to the need to improve the take up of, and outcomes from, its drug and alcohol misuse treatment services.

PHE works with local authorities and provides them with bespoke data, guidance, tools and other support to help them commission services more effectively.

PHE guidance for alcohol and drug treatment is available in the Alcohol and drug misuse prevention and treatment guidance collection.

A wide range of NDTMS data is available at the NDTMS website, including some data reports that are only available to local authority commissioners (via login).

The government’s strategy for drug treatment is set out in the ‘building recovery’ section in the Drug Strategy 2017.

-

Opiate and alcohol clients are likely to be excluded from the prevalence estimates due to the methods used, so are not included when calculating unmet need. ↩