Principles of screening

Core principles and elements of all screening programmes

Screening is the process of identifying apparently healthy people who may have an increased chance of a disease or condition.

Individuals can then be offered more information, further tests or treatment as appropriate.

A screening programme should only be recommended and provided if evidence shows the planned screening pathway, including further tests and treatment, will do more good than harm at reasonable cost.

Population screening is offered to large numbers of people (usually based on their age or sex), who do not regard themselves as having the condition being screened for and, as a rule, have not sought medical advice. It is the responsibility of the organisation offering such tests and treatment to make sure the programme operates at high quality to maximise benefit and minimise harm.

Targeted screening aims to identify people with a higher risk of a condition beyond demographics such as age or sex. Stratified screening offers testing tailored to individual risk. Regardless of this higher risk or the individual’s awareness of their own risk, the organisational responsibility remains the same.

Screening should always be a personal informed choice. Accurate, balanced, evidence-based information on the potential benefits and risks of screening should be provided at each relevant step of the screening pathway (see screening pathway section below).

Screening seeks to:

- prevent earlier deaths or improve quality of life by detecting a condition at a stage where treatment can be more effective (rather than waiting for symptoms to develop)

- reach everyone in the target population (see inequalities chapter

- reduce the chance of people developing a serious condition or its complications

- provide information for people to make informed choices

Screening tests are offered to large numbers of people so tend to be simple rather than very accurate. They look for indications that there may be an increased chance of a disease or condition. Screening often requires the offer of additional tests to confirm the presence or absence of a disease or condition.

No test is perfect and there will always be some incorrect results. These are usually described as:

False negative: a test result indicating a person does not have a raised chance of the condition but in fact they do have the condition.

False positive: a test result indicating a person does have a higher chance of the condition whereas in fact they do not.

False negative or false positive results can be harmful, as someone may either be falsely reassured or unnecessarily worried.

A false positive result may lead to someone having invasive or harmful tests or treatments which they do not need.

A false negative result may mean someone is not offered further diagnostic tests of treatment.

Some screening tests may also carry a small risk of physical harm, for example X-ray (radiation) exposure from a mammogram in breast screening.

Public opinion, rates of disease and technology constantly change. It is important to continuously review the case for new programmes, modifications to existing ones and to remain vigilant to the possibility that a health intervention other than screening might bring more benefit to the population. Screening programmes should be continuously monitored, quality assured, evaluated and reviewed.

Consideration of new programmes or programme modifications requires the involvement of groups of people who:

- have knowledge, expertise and interests spanning population health and care

- have an understanding of how tests function in large groups where the condition tested for is relatively uncommon

- understand the course of a condition in asymptomatic people

- can assess the harms, ethics and practicalities of helping large numbers of people understand what the screening offer is and deciding for themselves whether to accept without necessarily having contact with a clinician

- can set one form of public expenditure against competing others

- know how to diagnose, treat and care for people who are affected by the condition

These groups of people need to set all these considerations in the social context of their country. They will need to consider:

- if the health services can deliver high quality care

- how to undertake or interpret novel research and use it to design an appropriate screening programme

- the processes by which it is possible to maintain quality, safety and effectiveness throughout the life of the programme

The UK NSC carries this responsibility in the UK, using criteria based on the Wilson and Jungner WHO criteria. The committee then makes recommendations to government about the proposed screening programme introduction or modification.

This short video explains the possible advantages and disadvantages of population screening.

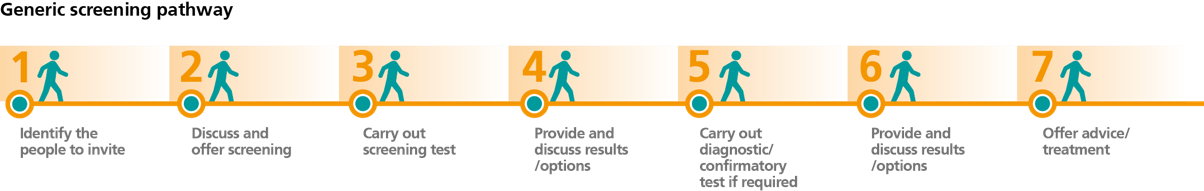

A nationally managed screening programme is not just about testing. No test on its own helps people. The test should be the right one offered to the right person, which is then followed up in order to make sure those needing further tests or investigations receive them. A screening pathway (illustration below) involves many different health professionals and services, often across different settings.

The steps listed below are common to all population-based nationally managed screening programmes and together they form the screening pathway. It is especially important to make sure that every eligible person receives an offer and supporting information, and each person who wishes to participate can access the whole screening pathway. In very large population programmes this is most safely done with an information system that identifies the cohort (the participants) and manages people through the pathway. In order to assess its effectiveness a screening programme should record health outcomes such as uptake, diagnosis and mortality.

Further detail about screening pathways can be found in the separate chapters of this manual for condition specific screening programmes.

People should be supported at each stage of their screening pathway.

Identify

It is important to ensure all eligible people are offered screening. Poor records or incomplete lists of people will mean that the screening programme will be limited in the benefit it can achieve. This would risk disadvantaging people who are not offered an available screening test, who may then go on to develop the condition screened for. Invitation mechanisms need robust access to accurate demographic data, which includes the variables required (following screening policy), sex and age being the most common. As this data will likely inform the list used to invite everyone, addresses, or other form of contact information, and unique identifiers are vital.

Evidence shows that those most likely to be affected by the conditions screened for may be least likely to accept or engage in the programmes. Missing such people not only reduces the effect of the programme but risks increasing health inequalities. Mechanisms to identify and engage such communities will vary between regions and countries, but their study and application are vital to a fair and effective programme.

In order to support informed choice, it is necessary to enable individuals to ask to be removed or temporarily suspended from the register of the eligible screening population, or to decline a current offer of screening.

Invite and inform

People having screening should have made an informed choice about taking part. A description of the condition(s) screened for, the screening process/pathway and possible outcomes, along with risks and benefits, will help support the person to decide if they wish to be screened.

Information in accessible formats to meet individuals’ communication needs will assist with wider engagement. Examples are easy read, picture-based, or audio resources.

The timing and location of all screening appointments should support, as far as practically possible, all eligible individuals to accept the offer of screening if they wish to.

People wanting to opt out of screening (either temporarily or permanently) should be provided with enough information to enable them to make an informed decision to do so (at any point in the screening pathway).

Efforts to ensure maximum informed engagement are important and may include reminders or prompts if an appointment is missed.

Test/screen

Consideration should be given to the geographical location and accessibility of screening clinics to support ease of access to screening for the eligible population.

To maximise benefit and minimise harm it is useful to establish and publish requirements for screening equipment and tests, including their maintenance and quality control where appropriate.

The workforce is essential to a safe, effective and acceptable programme. Ensuring they are trained and remain competent is critical. It is helpful to describe required competencies, which may include completion of additional training. These requirements are best set out and overseen at a programme level. Training and competency guidance should be kept under regular review and updated to reflect developments in the test, programme or workforce.

Where the tests are self-administered it is important to supplement the informed choice information with clear, quality assured instructions about how to do the test. Additional support will be needed by those who may experience difficulties accessing screening, for example people:

- with sensory impairment

- with a learning disability

- who speak different languages

- who struggle to access services

- who need a chaperone during a screening test

More information is available in the chapter on identifying and reducing inequalities in screening.

Results

It is good practice to give people their screening results within a reasonable timeframe. Screening tests are rarely definitive, so the results should be explained clearly and concisely. This may include explaining:

- that a condition, or an increased risk or higher chance of a condition, was not detected

- that a condition, or an increased risk or higher chance of a condition, has been detected and what will happen next

- that the test was inconclusive/invalid and what will happen next (for example, being invited for a repeat test)

- reasons for recommending follow-up appointments or tests if applicable

- if and when they will receive further invitations to the screening programme

There should be processes in place to:

- monitor and review results

- record results on a screening IT system, including any associated images

- monitor adherence to set timescales for testing and results

Diagnosis

A screen positive result should be followed by a diagnosis (and evidence-based treatment if required). Guidance and protocols are critical to an effective screening programme to ensure diagnosis and any subsequent clinical referrals are timely and of high quality.

There should be systems to:

- refer individuals to the relevant diagnostic or intervention service within a clinically agreed timeframe

- provide individuals with information on managing and monitoring detected conditions as appropriate

- monitor timeliness and completeness of referrals and offers of follow-up appointments

Treatment

Screening programmes should have links with appropriate treatment services. Capacity to diagnose and treat screen-detected conditions must be available.

There should be systems in place to:

- ensure everyone with a screen positive result is offered diagnosis (and treatment if necessary)

- enable appropriate clinical referrals to these services in order to maximise the benefits of screening and health outcomes

- monitor the timeliness of treatment and the health outcomes of individuals following treatment

- share post-treatment outcomes between the programmes and treatment services

All diagnosed individuals who opt for (and are fit for) treatment should be managed according to evidence-based practice and receive timely care.

Evaluate

Screening programmes should have processes in place to evaluate the safety, quality, effectiveness and outcomes of the screening pathway. This requires a range of activities, including:

- quality assurance

- setting of standards at specific points along the pathway

- monitoring and publishing reports on their delivery

It is important to monitor relevant screening outcomes for individuals, for example numbers of:

-

babies receiving timely penicillin prophylaxis

-

life years gained from treatment as a result of screening

- individuals losing sight due to diabetic retinopathy

- stage at diagnosis of cancer

- people with sight loss from diabetic eye disease

- successful operations for surgically treatable disease

- babies born without infections or receiving immunisations

It is also important to monitor wider population outcomes such as screening impact on mortality rates.

Comparison with international data (for example on screening uptake or coverage) can provide useful benchmarks. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has a useful tool to do this for bowel, breast and cervical cancer screening.

In the UK, the UK NSC recommends 3 types of nationally managed screening programmes.

These are distinct and separate from routine clinical care, in which a person with health concerns or symptoms may be offered tests by a clinician to assess their risk of disease.

The UK NSC does not recommend opportunistic screening or case finding. These activities rely on a clinician offering an individual attending for one condition a test for another condition (for which they have no symptoms or particular risk). There are many places across the world that rely on such opportunistic approaches, but they do not ensure engagement with the entire eligible population so risk missing groups of people who may benefit and risk potentially increasing health inequalities.

Population screening

A nationally delivered, proactive (individuals are actively invited for screening) screening programme which aims to improve health outcomes in people with the condition being screened for, and/or offer information to enable informed choices. It is offered to a group of people identified from the whole population, and defined demographically such as by age or sex.

Targeted screening

A nationally delivered proactive screening programme which aims to improve health outcomes in people with the condition being screened for, among groups of people identified as being at elevated/above average risk of a specific condition. Compared to the general population, the target population may be at higher risk because of lifestyle factors, genetic variants or having another health condition.

Targeted screening differs from population screening as it aims to systematically offer screening to more specific groups of people with a higher risk of a condition. For example, age and sex are factors in the risk of lung cancer, but individuals who smoke are at even higher risk.

Stratified screening

A nationally delivered, proactive screening programme, offering testing which varies in frequency and modality (varying types of test offered), according to the level of individual risk. This is designed to achieve a more favourable balance of benefits and harms at individual as well as population level.

Stratification is used in both targeted and population screening programmes, at the point of invitation as well as along the pathway. For example:

- people with a family history of breast cancer can be identified and screened more often depending on their level of risk

- people with high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) may follow a different cervical screening pathway than those without the infection

The UK NSC makes recommendations to government regarding which conditions should be screened for in the UK. It follows criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness for a screening programme.

Each UK country sets its own screening policy based on the recommendations of the UK NSC. This means there can be some variation in the screening offered.

See details of the screening programmes currently offered in each of the 4 UK nations.