Standard Essential Patent licensing

This guidance relates to Standard Essential Patents licensing.

Watch Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) Resource Hub: Part 2 Video on YouTube

1. Standard Essential Patent Licensing

Intellectual Property, like any property, can be bought, sold or licensed by its owner. A licence is a contractual agreement between someone owning intellectual property (also known as a rightsholder) and another party. An IP licence is an agreement under which the owner of an IP right grants consent to the licensee to engage in acts which would, but for that consent, constitute an infringement of the IP right. If something requires the consent of the IP owner to be lawful and is done without the consent of the IP owner, that would be an infringement of the IP owner’s rights. For example, a person infringes a patent for an invention if they do any of the things in relation to the invention which the patent owner has the exclusive right to do, such as (where the invention is a product) making, selling or using the invention.

A licence may include terms requiring the payment of a fee, from the licensee to licensor, in respect of the activities of the licensee which require the consent of the licensor to be lawful. A licence may also include provisions concerning the scope of the licence, such as the field of use in which the licensee has the licensor’s consent to operate, the territories to which the licence extends, and the period for which the licence is granted, amongst other agreed terms.

More information on licensing of IP can be found in the IP BASICS video:

More information on licensing of IP can be found in the IP BASICS: Should I license or franchise my Intellectual Property? YouTube video.

Patent licensing can incentivise investment into R&D as it can help the inventor to obtain a return on the investment in the development of that patented technology and facilitates the adoption of that technology. It can also enable re-investment into the next generation of technologies. For standard essential patents, licensing can be a way to obtain licensing revenue based on the value of the patented technology.

The IPO has guidance on what an example of an IP licence looks like, which can be found on the Skeleton Licence webpage.

A Standard Essential Patent is “A patent which protects technology which is essential to implementing a standard is known as a standard essential patent”.

For more detail on standardisation and SEPs see SEP guidance part 1 on Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisations.

This guidance is primarily aimed at UK businesses who require information on the licensing of SEPs, including when a licence may be required. It provides basic information on what to expect from a SEP holder and from a potential licensee. UK companies involved in SEP licensing are currently mostly SEPs implementers. SEP holders operating in the UK are mainly global in their operations, and are often US, EU or Chinese companies.

In some sectors or technologies that rely on standards, implementers of standards for which SEPs have been disclosed may not need a direct licence from SEP holders. For example, in some industries, the seller of the component to a product manufacturer will already have a SEP licence for the sale and use of that component by the product manufacturer, and therefore a further licence will not be necessary (value chain licensing is discussed in more detail in section 3).

Where a licence has not been concluded before standardised technology is incorporated in a product that’s on the market, the licensor will generally notify the potential licensee of its patents and licence offering. The focus of this guidance is on technologies where a licence is requested by a SEP holder.

1.1 Legal frameworks

SEPs are subject to the same legal and licensing framework as ordinary patents in the UK. There is no legislation in place to regulate the licensing of SEPs specifically. An overview of aspects of the legal framework that, combined, are relevant to SEPs is outlined briefly.

Intellectual property law:

There are various pieces of legislation such as the Patents Act 1977, that provide the legal framework for patent protection and enforcement in the UK. Interpretation of the legislation is addressed in a large body of case law.

Contract Law:

Contract law applies to licensing of SEPs, as it applies to all licence agreements executed under UK law and also comprises a mix of legislation and case law. Additionally, SEP holders will often have given licensing commitments to organisations which develop standards, which may be relevant to how SEPs should be licensed.

Competition law:

One of the main sources of UK competition law is the Competition Act 1998, which prohibits anti-competitive agreements as well as abuse of a dominant market position. Competition law is important to SEPs because it helps to provide a level playing field for businesses, to ensure that no business anti-competitively dominates a market, and it prevents businesses with substantial market power from using anti-competitive means to try to stop or hinder new companies from entering the market.

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) is the primary competition law enforcement authority in the UK.

The CMA has issued guidance to provide clarification on competition law matters, including for SMEs.

In Chapter 9 of its Guidance on Horizontal Agreements, the CMA covers standardisation agreements specifically, and the licensing and competition concerns that might arise in this area. For more detail, please see the Guidance on horizontal agreements webpage.

Case Law (court decisions):

The UK is a common law jurisdiction, which means that court decisions create a body of law, that other courts will follow. Recent cases in the UK involving SEPs have addressed issues such as FRAND licensing commitments (which includes assessment of a willingness by parties to engage in good faith negotiations), when injunctions could be applied preventing sales, and the calculation of reasonable royalty rates, including the methodologies for their calculation. The SEPs Resource Hub provides an up-to-date list of material UK SEP cases for information and awareness purposes.

In addition, some case law from the Court of Justice of the European Union remains relevant. The case of Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd v ZTE Corp (2015) is commonly referred to in the context of the parties’ behaviour in SEP licensing negotiations and available remedies.

1.2 The FRAND commitment

Owning a patent that is necessary to implement a technical standard can confer substantial market power, as implementers may have no option but to adopt these standards to bring or sell their interoperable technologies to the market. To protect against the potential abuse of market power, and to help ensure efficient dissemination of technologies on which standards are built, SEP holders are often required to provide a voluntary commitment at industry-led SDOs to offer licences on Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) licence terms as a condition to have their patent included in a standard. As well as allowing technology to be available, FRAND licensing enables SEP holders to seek compensation for the value of their valid, essential and infringed patents, and can ensure a SEP holder is prevented from engaging in anticompetitive conduct. A commitment to license on FRAND terms is not a type of licence. Rather, the commitment determines the terms under which licences of various types (including, for example, bilateral licences) must be offered.

What is Fair, Reasonable, and Non-Discriminatory licensing?

There is no formal or agreed legal definition of what constitutes FRAND. FRAND licensing principles apply to both the potential licensor and potential licensee.

However, some judges when dealing with SEP cases have ruled on what constitutes FRAND in several high-profile court cases globally based on the circumstances of those cases. Decisions in those particular cases have provided some degree of additional understanding on elements of FRAND licensing, particularly around when licensors and licensees are considered a ‘willing’ participant in negotiations or ‘acting in good faith’. There is more on this in Section 4.

FRAND’: an explanation

“Fair” and “Reasonable”are usually read in conjunction. It is also said that all three terms should be understood together rather than in isolation. Generally, FRAND means that the terms of the licence should not be anticompetitive and should be reasonable for both the patent holder and the licensee. It implies that neither party should gain unfair advantage. Examples of an unfair term would be to ask a licensee to license a bundle of patents which includes IP they do not need (also referred to “tying and bundling”) or more generally very restrictive conditions that could be deemed anti-competitive.

The licence terms should be appropriate to reward the patent owner for their investment in R&D and not be excessive. For example, royalties due and other terms should reflect the value of the patented technology included in the standard.

“Non-discriminatory” implies that the licensing terms should apply similarly to similarly situated potential implementers, without any distortion of competition. This is to ensure that everyone who needs access to the technology will be able to have access to a licence. This does not mean that everyone pays the exact same rate, there may be good reasons why some licensees pay more or less. Variations in licensing rate may be explained by what is included in the licence, for example there may be an off-set due to cross licensing, and other terms. However, through the development of case law it is understood that licensees who are similarly positioned in the market should receive similar (or also referred to as comparable) licences.

One of the aims of the FRAND commitment is to prevent something called “hold -up”. A “hold-up” refers to a situation where a SEP holder exploits their position and charges excessively high royalties, and the licensee believes they have no choice but to pay. Without a FRAND commitment, and the SEP holder not complying with that commitment, the SEP holder may have a strong bargaining power with respect to potential licensees. It may be that potential licensees have no alternative but to license the patent if they wish to enter the market covered by that standard, or perhaps have already implemented a SEP-encumbered standard into their technology and now require a licence. Higher royalties can mean higher prices are passed on to consumers.

On the other hand, ‘hold-out’ refers to a situation when a potential licensee unreasonably refuses, or excessively delays entering into an agreement to take a licence to a SEP(s) in order to put pressure on the SEP owner to provide more favourable licensing terms or force the SEP holder to commence infringement proceedings to obtain a court adjudicated decision. The potential licensee may believe that a court determined FRAND rate may be more appropriate than a rate decided by way of a bilateral negotiation.

2. Types of SEP licensing

SEP licensing may include voluntary commitments that arise out of participation in standard development and the SDOs’ IPR policies. The appropriate SEP licensing practices and considerations can also depend on other factors; certain industries have certain licensing models, and the relevant practices and considerations can depend on the use of the particular technology. Potential licensees should carefully consider the relevant licensing practices and considerations and the available licensing options, and also consider seeking professional legal advice.

Licensing of SEPs can at times be a complex landscape to navigate, particularly as licensing often happens in a global context reflecting the global nature of technical standardisation and the use of standards.

2.1 Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) commitments in Standard Development Organisations (SDOs)

IPR policies of SDOs (see Guidance on Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisations for examples of SDOs) are critical in SEPs licensing as they govern how patents, copyright, and other IPRs are managed in the standards development process. SDO policies typically aim to balance the objective of wide adoption of standardised technology for the benefit of the public, with the rights of holders of patents that have voluntarily committed their patented technology in the standard in the expectation of receiving compensation on FRAND terms from those who implement their IPR.

SDOs have their own rules and procedures that relate to the type of technology that is developed as part of the standardisation process. Not all SDOs require participants to license their IPR, or to disclose the IPR that may cover a standard. Some SDOs, such as the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), provide for royalty free licensing. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Standards Association (IEEE-SA), another SDO, does not require participants to disclose or declare patents that are part of the standard – although providing a declaration (referred to in the organisation as a Letter of Assurance) is expected. The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) requires that its participants disclose their patents but does not require a licensing commitment. Participants instead provide their own bespoke assurances of access to the standard developed without infringing their disclosed patents. Conversely, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) requires disclosure of IPR and seeks FRAND licensing commitments from its members.

The intention of this guidance is to provide an understanding of the technology areas in which the adoption of technical standards and the existence of associated SEPs are most common, and in which SEP licensing is typically required because of the standardisation process. Commonly, IPR policies of SDOs can include the following key commitments which shape typical licensing for standardised technology (please refer to the Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisation Guidance for more on ‘disclosure’ and ‘declaration’):

- disclosure requirement: an SDO may ask its members contributing to the development of a standard to make reasonable efforts to disclose patents and other IPR that are or may become essential to the relevant standard. This may provide an idea of who has participated in standards development and what the patent landscape might look like

- declaration of licensing commitment: SDOs may seek voluntary commitments from contributing members to make their IPR available to third parties to license to ensure the inclusion of their patented technology in the standard. Some SDOs may require that the licensing commitment is to grant licences of the patented technology and other essential IPR on Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) terms

Taking into account the relevant SDO IPR policy, and compliance of relevant laws set out above, the licensing of SEPs is determined by the same legal frameworks as any other IPR.

2.2 Typical licensing models

There are a number of licensing models, such as bilateral, portfolio and global licensing, to name a few, many of which are not mutually exclusive. Certain commercial practices may be dominant in certain industries, but that does not make them universal or mandatory. Where SEP holders choose to license (including when they give a voluntary FRAND commitment to an SDO), licensing may happen in the ways set out below.

2.2.1 Bilateral licensing

Bilateral licensing is a common type of licensing that happens between two parties, i.e., the SEP holder (licensor) and SEP licensee, where there is an attempt to come to an agreement between both parties on the terms of the licence.

Portfolio licensing

In the context of SEPs, a patent holder may typically offer to license a package or portfolio of multiple IPRs relevant to the implementation of a standard. This is referred to as portfolio licensing, and this model of licensing is common. It is also understood that large portfolios that are subject to the licence will encompass all patents that a patent holder considers to be essential to a standard. Some SEP holders may also license more broadly, and as a result may offer to include non-essential patents in a licence. The licensee may choose for the licence to be limited to only actual SEPs (or what they may think are actual SEPs), and in that circumstance the SEP holder must be willing to license those SEPs. However, a licensee may also want the additional coverage from a broader licence. This may provide coverage for patents not essential to the standard as well as those that the licensor contributes to the standard after the licence is signed.

This is typical of the dynamic nature of portfolio licensing as it contemplates that new SEPs will come into existence during the term of the licence and some SEPs will expire or be deemed non-essential. A SEP portfolio licence can anticipate these eventualities and prices should reflect this.

Typical advantages to portfolio licensing may include:

- simplification of the licensing process by avoiding the need to invest time and resources in the negotiation of separate licences or separate licensing terms for multiple different SEPs and other IPRs and making the process more efficient for both parties

- reduction in due diligence costs, as it does not necessarily involve a patent-by-patent assessment of the validity and essentiality of the entire portfolio and recognises an acceptance by both parties that there can be no absolute certainty about the essentiality of every SEP in the technical standard (ultimately only a court can make that determination at present)

- reduction of risk of future litigation for patent infringement as all the relevant patents of that specific patent owner are likely to be included within the scope of the portfolio licence

Typical disadvantages may include:

- large portfolios may well contain some patents that an implementer or potential licensee may not need to licence because (i) they do not use the technology, (ii) one or more of those patents may not be valid, (iii) one or more of those patents may not be truly essential to the standard. This means that a potential licensee may accept an obligation to pay licence fees in respect of patents and other IPR for which they may not require a licence (but may still do so to eliminate the due diligence cost and litigation risk associated with not taking a licence)

- concluding even a portfolio licence with a single patent owner, does not mean that a potential licensee has acquired rights to SEPs owned by others and does not avoid the risk of litigation with other SEP owners regarding the same standard or product features used by an implementer when complying with a standard

Global portfolio licensing

Patents are national rights which are granted (in accordance with the relevant national or regional application and examination procedures) on a country-by-country basis. Patents for the same inventions can exist and be valid in many countries. It may be the case that a potential licensee wants to license all a SEP holder’s patents or IPR relevant to a standard on a global basis so that the licensee can manufacture or market standardised goods worldwide. This approach is known as global portfolio licensing and is common for SEP licensing relating to mobile communications and video standards for example.

This approach to licensing can be advantageous (for both the licensee and to the relevant SEP holder) because the licensee can operate globally and not worry about being unlicensed to use the SEP holder’s relevant technology in other countries in which they operate. It can also provide some clarity on potential financial liability by making IP budgeting and financial forecasting easier.

However, it may be the case that negotiating parties want a licence covering only the geographical areas in which a potential licensee is operational so that the potential licensee does not feel that they are overpaying for what they need. For example, a potential licensee may want to operate in just the UK, or just in Europe, and having to license a global portfolio may be more costly than taking a licence to operate only in selected territories.

2.2.2 Cross-Licensing

Cross-licensing involves the exchange of patent licences between two or more parties where the parties each grant a licence to the other party. For example, in the context of SEPs, if both parties are SEP holders, a bilateral licence can include a cross-licence, where each party grants a licence under its SEPs to the other party.

A cross-licensing agreement may help to ensure mutual access to standardised technologies, and potentially with reduced or no royalty payments. This can be efficient where both parties to the licence agreement own portfolios of relevant SEPs but may not be a licensing model possible or suitable for small or new companies to a market with limited or no SEPs.

2.2.3 Collective licensing or SEP related licensing pools

Licensing pools, or ‘patent pools’ as they are commonly described, relate to at least two patent holders agreeing to contribute their patents to a ‘pool’ or package of IPRs that is licensed. Each contributor typically enters into a licensing agreement with the pool, wherein the pool may grant licences to licensees, on the members’ behalf, in respect of all patents contributed by or declared essential by the members of the pool. Associated royalties are then allocated to each member and to the pool administrator according to agreed rules.

A pool administrator is an organisation that is appointed by the rights holders (SEP holders in this case) to license the pooled patents to third party licensees on common terms and conditions. Pool administrators of SEPs will usually arrange for an independent expert to assess the essentiality of the patents against the standard and offer SEPs as a package to licensees.

When patents are licensed through a pool, a potential licensee has the option to either license a SEP bilaterally from the relevant SEP holder or through the pool. Patent pools are particularly common in industries where a licence under multiple complementary patents is necessary for the implementation of a particular technology or standard. They have been used in the video and audio codec standards, and mobile communication standards (4G and 5G) in the automotive industry.

Key advantages of patent pools may include:

- efficiency of licensing: they can provide manufacturers with one-stop access to multiple patent licences required for the lawful use or sale of a particular product or service, thereby avoiding the need to negotiate multiple licences. However, a pool is not guaranteed to include all patents necessary to implement a given standard

- reducing transaction costs: can potentially mean a reduction in negotiation and administrative costs for both SEP holders and licensees

- minimizing the possible risk of royalty stacking and patent thickets: Royalty stacking may happen when there are many patents covering a standard, or parts of a standard, and many licences from different SEP holders may be needed for the implementation of a standard. Navigating a complex web of many patents (sometimes referred to as a “patent thicket”) requires expert knowledge. A patent pool can offer a single licensing agreement that includes a number of patents needed to implement a standard for an agreed rate

- financial planning: Royalties for patent pools are known in advance. This can make budgeting, financial planning and managing risk easier. Patent pools often offer discounts and other benefits and it is important to be aware of these opportunities

Possible disadvantages with pools:

- the pool administrator may not be independent of the SEP holders. As such, potential pool licensees should conduct appropriate due diligence on the pool and its administrator to ensure that they are informed about the commercial context relevant to the establishment and operation of the pool

- the essentiality assessments undertaken by a pool may not be carried out on a fully independent basis (i.e., they may be carried out by the pool members or administrators who are likely to have a vested interest in a patent being assessed as essential) and may not be publicly available

- some SEPs may not be included in the pool, meaning that the licence granted by the pool administrator may not extend to activities which require the consent of the holder of those other SEPs. A licensee may still need to contact those other SEP holders.

- pools may seek to license the same patents under multiple pools for similar standards used in the same products, and potential pool licensees should conduct appropriate due diligence to satisfy themselves that they are not paying more than once for the licence they require

In some circumstances, patent pools can be an effective mechanism for managing intellectual property rights and facilitating SEPs licensing, particularly if the pool complies with FRAND licensing principles. However, careful consideration of the benefits is necessary and professional or legal advice should be obtained when considering their use.

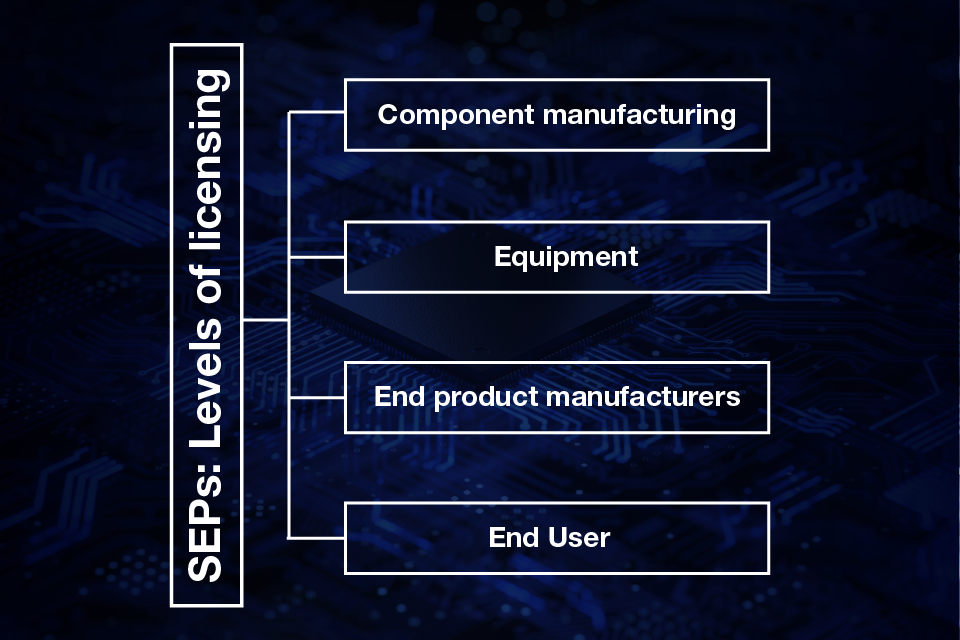

3. Where in the value chain does licensing of SEPs take place?

There are various points in the value chain where an implementer may need or want access to standardised technology. Licensing usually occurs at only one point (to avoid competition law concerns) for example at component level or end user product level, and this is usually determined by the SEP holder but can also be industry-specific.

Licensing practices do change over time, with standardised technologies being implemented across many more sectors now (see guidance on Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisations). Where licensing takes place in the value chain is usually due to a combination of technical, legal, economic, and strategic factors. Regardless of where licensing takes place, whether at a component level or end user product level, it is understood that a licence on FRAND terms should be available. Some SDOs, such as IEEE-SA, include specific wording that a SEP holder ‘will make available licences to an unrestricted number of Applicants worldwide’. Other SDOs require the participants to declare their willingness to grant licences but are silent on the point of licensing in the value chain and on consequences for SEP holders who do not allow access.

Licensing to End User Product Manufacturers

SEP holders may directly license their patents/SEPs to manufacturers, who make products that are built for end-users, such as PCs, mobile handsets, or automotive vehicles.

This approach of licensing to end user product manufacturers may provide efficiencies for SEP holders (i.e. in the form of reduced administrative or transaction costs) because royalties based on sales are easier to establish and potentially to audit. Licensing at the end user product manufacturer level may also generate more licensing opportunities and is also where many of their SEPs may be infringed.

Licensing to Component Manufacturers

There are a number of examples of component manufacturers, for example computer chip manufacturers or wireless modem manufacturers. Component manufacturers are generally placed ‘upstream’ where the licensing of SEPs occurs. Component licensing is particularly relevant when the patented technology is embodied in one or a set of components rather than being directed to the entire end product.

Licensing at component level can provide efficiencies in the form of reduced transaction costs, as a single licence can then flow through the value chain, rather than requiring multiple licences to be agreed with multiple downstream users of the same component parts. While there is often a limited number of component manufacturers, the same components can be used by many more end user product manufacturers.

Many component and equipment manufacturers have pre-existing licences to make and sell products protected by SEPs. Implementers should consider communicating with their suppliers to verify and identify any relevant licences they have and whether the scope of those licences extend to the implementer’s intended use.

Implementers should also consider whether or not a SEP licence granted to its supplier may exhaust any relevant IP rights. The concept of exhaustion of IP rights refers to the principle that once a good has been lawfully placed on the market by or with the consent of the IP rights owner, the IP rights holder loses the right to control the further distribution or resale of that good in most circumstances due to the UK’s exhaustion regime.

Currently, the UK’s exhaustion regime ensures that once a good has been lawfully placed on the market by or with the consent of the IP right owner in either the UK or the European Economic Area (“EEA”), the relevant IP rights in that good are considered “exhausted” in most cases within the UK. After this, the rights holder cannot use their IP rights to control the distribution of the good (e.g., prevent the import of the good from the EEA into the UK). The government is currently deciding what the UK’s future exhaustion regime should be, which may affect the territorial scope of the UK’s exhaustion regime.

If the patent is considered “exhausted” in the UK, then it may be that the implementer does not require a further licence to use the component supplied for the purposes required by the standard. Here, the patentee is also prevented from collecting royalties more than once within different levels of a supply chain for a particular good once it has been placed on the market by or with the consent of the IP right owner. The government would recommend that any implementer considers obtaining professional, independent legal advice to assess whether a licence is required for their operations.

If a supplier or customer does not have a licence, communication with them is still desirable because they will very likely understand the technology and the patents. This may turn on the resources available for obtaining technical and patent advice. Where there is an NDA in place with the Licensor, the permission of the Licensor will be required to share any confidential information the Licensor provided to you with your supplier. You should also verify in your supplier/customer contracts your conditions and level of indemnity because products can be sold with an IP right indemnity attached.

4. Typical IP licensing journey & FRAND negotiation process

Although there can be significant variation in licensing journeys there are often some similarities in the steps taken. The section below tries to capture those similarities by providing some typical steps in respect of SEP licensing. This guidance is for information purposes only. It should not be relied upon when taking business, legal or other decisions. Appropriate professional advice should be sought.

4.1 Notification of rights:

A licensing negotiation often starts with a SEP holder informing the potential licensee, in writing, regarding their ownership of declared SEP(s) and the availability of a licence on FRAND terms. When a SEP owner believes someone is using their SEP protected technology without permission and they wish to license them, they should notify them of this and provide sufficient information to support their belief of an infringement of their SEPs. This happens particularly when the SEP holder believes its patented technology is essential to the implementation of the standard, and that an implementer is implementing that standard without the necessary licence. A licensing negotiation can also start when a potential licensee contacts a SEP holder to request a SEPs licence. This can happen if the potential licensee has been engaged in the development of the standard or involved in its evolution or preparation for its implementation in the market.

Once notified by the SEP owner of the SEPs and any other relevant IP rights, the implementer (potential licensee) may consider:

- rejecting any notice or warning letter received, and in doing so, risk infringement proceedings being commenced and potentially being the subject of a court order (in the form of an injunction) requiring them to stop using the patented technology

- opening discussions with the SEP holder and commencing negotiations on a FRAND licence

This may be an appropriate point in a licensing journey to seek legal advice.

4.1.1 Dealing with confidentiality:

Prior to disclosing details about technology which is subject to a potential licensing arrangement, it is common for parties to a negotiation to sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) if confidential information is being exchanged. Information on the patents, standards and essentiality may be publicly available and may not need to be disclosed under an NDA.

An NDA is a legal contract and often known as a ‘confidentiality agreement’. It sets out the parties’ respective obligations in respect of information or ideas which are disclosed in confidence. An NDA is normally entered to give the parties an opportunity to evaluate the technology and assess whether a licensing agreement is necessary or appropriate. It is worth noting that patent pools, which generally offer standardised licensing terms and rates, often make their licensing documentation available without confidentiality restrictions and do not seek to obtain confidential information from potential licensees, other than periodic royalty reports that are provided over the course of the licence. It is advisable to obtain legal advice to check that an NDA is not overly restrictive and allows sufficient freedom to make decisions, e.g., allows for sharing certain information with your suppliers or manufacturers, and also provides what confidential information is going to be shared.

The IPO provides guidance and template documents for using a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). An example of a Mutual Non-Disclosure Agreement is available following this link.

4.1.2 The evaluation period – technical phase:

Following the signing of an NDA in the context of a potential licensing arrangement, the evaluation period provides the opportunity to conduct due diligence, including the analysis of the licence and patent portfolio, and comparable agreements.

If a business will use technology or other assets which are protected by third party IPR, time should be spent undertaking due diligence. If looking to incorporate standardised technology in products, then it is helpful to look at the source of that standard (i.e. identify the relevant SDO) and see if there is an IPR database to identify who contributed to the development of the technology required for implementation of the standard, and who disclosed that they may own SEPs relevant to that standard (see also paragraph 4.2.1). This should help establish whether or not the patents included in any proposed licensing arrangement includes all of the patents which have been disclosed as essential to the standard that are necessary for implementation in products.

Due diligence in relation to the patents proposed to be licensed may include (amongst other things) assessment of their technical scope, their geographical scope, their validity, their ownership, their likely enforceability, and the economic value that can be derived from a licence to exploit the technology they protect.

The due diligence process should also be used to investigate whether the proposed licence is required or whether use of the technology in question is already licensed via another route. For example, a potential licensee may be entitled to use the technology as a result of a licence granted to a component manufacturer which permits the downstream sale and use of the component in question (also see section 3). Where in the value chain licensing takes place? for further detail). The evaluation period may also include an assessment about the essentiality of SEPs. More detail on ‘essentiality’ is discussed in guidance on Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisations.

4. 2. The negotiation phase:

Negotiations should be carried out in good faith, which is a concept that is recognised in English law and refers to an overarching concept of ‘fair and open dealing’. It refers to the obligation on parties to engage in negotiations in an honest and fair way. In the context of SEPs licensing this normally means agreeing terms that are FRAND in accordance with the declaration given by the SEP holder and required of the SDO responsible for setting the standard.

The negotiation phase can take time, sometimes years, and can consist of several rounds of offer and counteroffer. The duration of the negotiation phase can depend on many factors such as the scope of the portfolio of IPRs potentially being licensed (the IPRs included in the licence, geographical coverage, field of use, etc), reservations about the validity of any patents including within the licence (particularly where significant value is attributed to those patents by the licensor) the complexity of the technology, whether there are assets to cross-licence, and other terms such as payment mechanisms.

The SEP holders’ offer should comply with their FRAND commitment, and potential licensees should typically expect the SEP holder to identify the relevant standard to which their technology relates, and receive the following information from the SEP holder:

- a list of IPRs (SEPs and any other relevant IP) proposed to be included within the licence and the relevant standard to which each IPR relates

- a sample set of claims charts as an example of how the features of the SEP holder’s patents map across to the standard to which the technology relates. Please refer to the guidance on Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisations or more information

- the offer must include a proposed FRAND royalty rate and the manner in which that rate is calculated

If the SEP holder has not provided sufficient information to support their FRAND offer, the licensee may reasonably request additional information. Typically, the SEP holder will indicate a reasonable deadline for the implementer to respond to their FRAND offer.

Where the potential licensee has already been implementing the SEP owner’s SEPs without a licence, the Licensor would expect to receive the following information from the potential licensee:

- information on products implementing the standards

- sales volumes

- territory of potential licensee’s business

If the potential licensee does not engage, there is an increased risk that the SEP holder may seek judicial remedies that may include a request for injunctive relief.

The potential licensee can accept the offer or make a FRAND counteroffer.

- if the potential licensee makes a counteroffer, it should also provide details of the way in which their proposed royalty rate is calculated, together with suitable arguments

- at this stage the potential licensee is not prevented from challenging the validity of the patent and its essentiality, and can ask the SEP owner if there have been any court decisions on validity or infringement, or royalty rates determined for the same patents by a court

- revised offers and counteroffers can be iterated multiple times between both parties

4.2.1 How do I know I am getting FRAND licensing terms?

Licensing standardised technologies can be complex and will require careful analysis that may include analysing the patent (and portfolio) itself, market conditions, industry standards and the terms of the agreement itself and other (including comparable) licences entered into by the licensor (if available to the potential licensee).

Consult experts (legal/technical). They can help you understand market dynamics and assess the terms of a contract and assess if they may be consistent with FRAND terms

Because SEP licensing is complex it is best to obtain professional, technical and legal advice. The IPO has a link to such services within the Seeking intellectual property advice webpage.

The information below may also help you to better understand how to navigate the issues and what to get further expert advice on:

Understand the Industry Standard

A SEP owner should provide information about the standard to which they claim the technology protected by their SEP is essential. Potential licensees should refer to the relevant SDO where the standard in question was developed for more information. It may be necessary to engage an expert who can help to assess the standard and the patent claims asserted against your products, as navigating and understanding standards and patent claims can be an extremely difficult exercise. There are some offerings on the market that may help to understand the standard and patent declared as essential. But these tools should not be used in isolation, and manual verification may be necessary. There may be a database of disclosed SEPs for information on the potential essentiality of the SEP e.g., ETSI has a database of SEPs disclosed.

Attending industry events may be helpful, or events at an SDO relating to the standard. Speaking with others in the market, reading up on data or industry-specific publications, is another way to gain intelligence and insight into the industry standard.

Understand the coverage of the SEP(s) in relation to your product:

When faced with a request for royalties or a proposal (or demand) to take a licence, it may be sensible to conduct a technical analysis of those parts in a product alleged to use the SEP(s) in issue. It may be worth considering the value of the aggregate technology, particularly compared to non-patented aspects of the product, and whether or not there are non-patented or non-essential alternatives. A potential licensee should also check with suppliers and customers to see if they are licensed already. See also paragraph 3 on licensing in the value chain.

Understand comparable licences and market rates:

Assess if the rate offered is in line with prevailing market rates for similar technologies and similar patents. Research and analyse previously concluded licence agreements for similar patents entered into by the licensor. This is a difficult exercise given that in licensing negotiations commercially sensitive information is usually protected by NDAs that are not in the public domain. This may require conducting market research or consulting an industry expert.

The SEP holders’ website may list “rack” rates, but these may not be representative of true comparable licence agreements. The negotiation parameters should be checked, as should the availability of comparable licences (with identifying information of the licensee removed due to confidentiality). The websites of patent pools may also be checked, as could relevant SDO websites, or court decisions where rates have been determined. SDOs do not provide information on SEP licences, and most court decisions redact comparable licence terms for confidentiality purposes. There is, unfortunately, no one database with comparable data available at this time.

Consider aggregate rates:

An “aggregate royalty rate” means the total amount of royalties payable for licences for all the patents that have been disclosed as essential to a standard. There is currently no formal means of determination of the total royalty burden for a standard although there are different methodologies to calculate an aggregate royalty with great variations in outcome. However, it is important to have regard to the aggregate (i.e., total cumulative) royalty burden under all licences which are likely to be required so that you understand whether the royalty being demanded by the SEP holder is reasonable relative to the standard as a whole. This may mean asking the SEP holder for reasoning behind the rate they ask for in light of their share of SEPs from the total stack in a standard.

Evaluate all other Terms and Conditions:

Potential licensees should carefully consider all terms and obligations and assess if they are reasonable and not disadvantageous compared to other licensed competitors in the market. Professional or legal advice in this respect should be considered.

4.3. Agreement and contract:

Once the terms of an agreement have been reached, they should be recorded in writing and clear evidence of agreement by both parties should be captured so that there is a record. The agreement should also include each of the warranties and representations made by each party which have been relied upon by the other party when agreeing the terms of the agreement. This record is called a contract (which may be a licence or include a licence as part of the agreement) and will stipulate many other terms. The IPO has guidance on the Skeleton Licence available, as one potential format example.

If offers are rejected and the negotiations are not successful, before a SEP holder may apply to a court for an injunction to stop the potential licensee from using the patented technology which is protected by their SEPs, and for damages in respect of the unlicensed use of that technology before any such injunction is granted. Alternatively, if a potential licensee’s counteroffers are rejected and the negotiations are not successful, a potential licensee may apply to a court requesting a FRAND determination. Courts in the UK have been setting global FRAND royalty rates in SEP disputes. The SEP holder will need to demonstrate that their SEPs are valid and infringed. More information can be found in the SEP Case Law.

If an agreement cannot be reached there are resources available covering dispute resolution solutions within the guidance on dispute resolution and remedies in SEP licensing.

4.4. Implementing the agreement:

Once the licence/contract is signed, the implementation of the agreement can start. This includes fulfilling any obligations mentioned under the licence terms. These can include paying the agreed sum or, if applicable, reporting of sales figures, paying fees, milestone payments, royalties, cooperating with audits, etc.

For the continuance of a mutually beneficial relationship, it is good to resolve any disputes quickly. This will ease any new licensing negotiations if and when the licence is due for renewal. If disagreements persist and cannot be resolved amicably between the parties, there is guidance available for using ADR services within the guidance on dispute resolution and remedies in SEP licensing.

5 ‘FRAND’ Royalty rate calculation methodologies

Determining a FRAND royalty is complex. There are different methods for calculating a royalty, and much will depend on the individual circumstances. There is no single methodology that fits all licensing situations. Each methodology has its advantages and limitations depending on availability of data, complexity of the technology, industry practice, maturity of the standard, inflation, value and age of the patent(s). Court litigation concerning SEP licensing often raises the calculation of the royalty rates as an issue to be determined, which can be accompanied by a request to see comparable licences. More detail on these court cases can be found in the UK SEPs Case law section of the SEP Resource Hub.

Payment clauses can vary and may refer to licence fees calculated on sales volumes (royalties as a per-unit £/$ amount, as a percentage of the sales value of a product or component (known as an ad valorem rate), or a fixed ‘lump sum’. It is important that a potential licensee understands any payment mechanism, their obligations and the implications this has on their business strategy, operations and budget.

6. Further IPO SEPs Resource Hub Guidance

- Introduction

- Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisations

- Dispute resolution and remedies in SEP licensing

- International Signposting

- UK SEPs Case Law

- Glossary of terms

Intellectual Property Office and further support:

-

IPO Information Centre: 0300 300 2000 / Email:information

-

World Intellectual Property Office WIPO: WIPO Strategy on Standard Essential Patents 2024-2026

7. Disclaimer

The information on the SEPs Resource Hub is for guidance purposes only and does not constitute legal, business, financial or other professional advice and should not be relied upon when taking IP related, business, legal or other decisions. The IPO is not responsible for the use that might be made of this information. Appropriate professional advice should be sought. The SEPs Resource Hub is not a substitute for proper legal advice. Every effort is made to ensure that the information provided is accurate and up to date as at the time of publication, but no legal responsibility is accepted for any errors or omissions.

The IPO provides guidance on how to find Specialist and Legal IP Support in the Seeking intellectual property advice webpage.