Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisations

This guidance relates to Technical Standards and Standard Development Organisations to describe the typical first step in a Standard Essential Patent (SEP) journey.

Watch Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) Resource Hub: Part 1 on YouTube

1. Technical standards and standardisation

1.1 Introduction

Our everyday lives increasingly rely on technical standards. This guidance focusses on ‘technical standards’, sometimes referred to as ‘technical interoperability standards’. Technical standards are collectively and voluntarily agreed ways that specify how technologies interact with one another regardless of who manufactures the product.

Typical examples of where technical standards may be encountered in everyday life include mobile telephone handsets seamlessly communicating between different brands and across borders, broadcasting technologies that can be relayed on different television products, or their application to cars or other vehicles to update you with the latest traffic information or to allow driverless cars and drones to operate safely. There are many sectors or industries such as digital healthcare and connected homes where technical standards are essential to enable interoperability across different brands. A list of the sectors where you commonly find technical standards is set out in section 3.

Definition of a technical standard

“A technical standard is an agreed technical description of an idea, product, service, or way of doing things where you need to share the understanding with others.

These are usually produced by standard developing organisations (SDOs), established for the purpose of creating standards, with inputs from industry, government, academia and other technical experts.”

IPO working definition, from: Standard Essential Patents and Innovation: Call for views.

1.2 How standards are developed

Technical standards are complex and detailed documents that describe a collectively agreed technical solution, for example, the expected operation (and interoperation) of a cellular network and devices within that network necessary to enable interoperability and technical performance requirements. Technical standards are often subject to continuous development. For example, in the telecommunications space, technical standards have been developed through several generations from GSM (2G) to 5G, and now 6G is being planned for development.

Technical standards are not to be confused with quality or safety standards, although technical standards are also used for quality and safety purposes. In the context of SEPs and essential intellectual property rights (IPRs), we refer to technical standards as ways to make devices work together seamlessly. There are other standards that are designed to ensure the safety of our products, or standards that serve as a quality check for any industry. These standards are outside the scope of this guidance and the SEPs Resource Hub more generally.

Technical standards can take years to develop and can be based on previous generations of existing technologies and standards. The process of developing standards or ‘standardisation’ is done by many organisations (for example industry, academia, government organisations) coming together to develop these technologies through (often international) technical cooperation within a host SDO (also known as Standard Setting Organisations (‘SSOs’)). SDOs often focus on a particular area of technology.

Representative engineers from SDO member organisations work together voluntarily and agree on the technological solutions to be adopted for the standard. Often these meetings identify technical problems to overcome. Through consensus, solutions are identified by the participating engineers and the resulting technical solutions may be novel, and inventive, and therefore eligible for patent protection. More information on patents can be found using the Intellectual property and your work webpage.

Once participants have agreed upon the final version of a standard it is adopted by the SDO and typically published, to be used by companies to implement the standards into their products such as mobile phones, computers, televisions and cars. An example can be found in the Download ETSI ICT Standards for free or IEEE SA - Standards, (please note that access to standards is not necessarily free). Together, the participants in the standard setting process are able to achieve what no single organisation could have achieved alone.

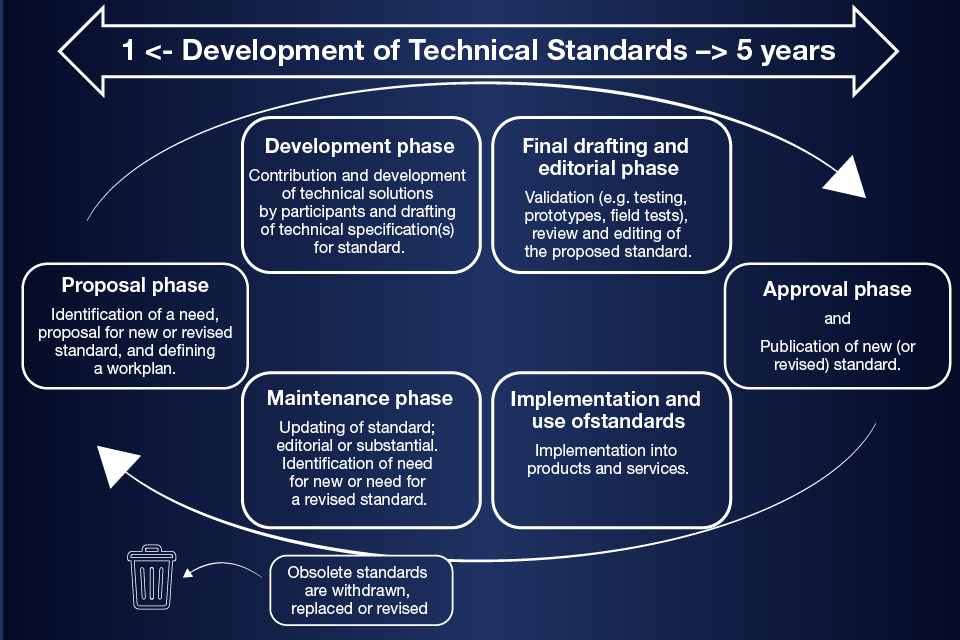

The flowchart below describes an overview of a lifecycle of the development of a hypothetical technical standard. Technical standard development begins with the ‘Proposal Phase’, which is the initial identification of a need for either a new or revised standard, or the identification of a particular technical problem to overcome. Participants will define a work plan, and once this is accepted it will go through a Development Phase. The ‘Development Phase’ is where expert participants contribute to the drafting of the technical specification of the standard. Once the standard has gone through testing and validation e.g., testing of prototypes, which may include a number of revisions, it will move to the ‘Approval Phase’ by the SDO. Once an SDO has approved the new or revised standard it will be published and the standard is now ready for implementation into products and services, and available for use by end-users.

Standards continually evolve, and will need reviewing for a new or revised standard. This is referred to here as the ‘Maintenance Phase’. Standards can become redundant or obsolete and may be withdrawn or replaced, where the ‘Proposal Phase’ is undertaken again, and work starts on the revision or creation of a new standard.

Development of standards takes time and standards can go through many iterations before consensus is reached on the final version, but very generally speaking it may take about 5 years. Variation on the 5 years will likely be associated with technical complexity and industry participation.

Please refer to the SDO table to find out more about the specific processes in place for each SDO. One example is CEN/CENELEC where European standards are developed, the webpage European Standards - CEN-CENELEC outlines the steps in their development of European Standards.

Organisations which contribute technical know-how to the standardisation process should consider, before making any disclosure of know-how which is not already in the public domain, whether to take steps to protect that know-how from unauthorised use, such as through the use of NDAs and/or the filing of patent applications.

Patentable inventions devised during this process which are relevant to the implementation of the standard may also go through a lengthy patent filing process in multiple jurisdictions. An average patent can take anything from 3-5 to 10 years approximately from filing a first (known as priority) application to being granted. These patentable inventions may or may not form part of the final agreed standard. It is also important to note that not all parts of standards may be covered by patents. It is important to have a good understanding of the relationship between IPRs and standards.

The diagram below represents the patenting process from ‘idea’ to ‘grant’. The patent process flowchart explains that following the initial inception of an idea, it is important to obtain professional advice to assess whether this idea is patentable, and whether it is commercially viable. Following this assessment, the initial patent application may be filed at the UK IPO (or other national or international patent filing office). The patent will then follow a formal process where a ‘search’ will be conducted by the Patent Office to assess if a similar idea has been patented before. After this phase the application is made public, this normally happens at 12 months with a ‘publication’. The patent application will then go through a process of ‘examination’ and during examination amendments can still be made, until the patent application is approved by the Patent Office. In the UK, the UK IPO may then issue a ‘Grant’. Following the Grant of a patent, there will be a ‘maintenance’ period and renewal fees may be payable.

The UK IPO has extensive resources available on the patent process and the importance of IP for businesses and research. More detail, and access to slides on all IPRs, including patents, can be found in the IP for Research Fundamentals Toolkit webpage.

2. What are Standard Essential Patents (SEPs)?

A patent is an exclusive right granted for an invention. Patents protect new inventions, whether as a product or process/method or both. Patents allow the holder to prevent certain acts by others, such as the use without permission of the patented technology for a limited period of time.

SEPs are ordinary patents with the difference that they are essential to practice a voluntary, collectively developed standard and may furthermore be subject to a commitment from their owner to make them available on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms, in accordance with the IPR rules of the SDO where the standard was developed. Any such FRAND commitment varies between SDOs, and is further discussed in Section 4 .

In the absence of a court determination as to whether a patent is a SEP, there are several definitions that help determine whether a patent is essential to the implementation of a standard. This is referred to as its “essentiality”. An example of where essentiality is defined is at an SDO called the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) where some of the standards in ICT and telecommunications are developed.

ETSI define it as (ETSI - Intellectual Property Rights policy and IPR online database):

Definition of Essential IPR (ETSI IPR Policy Clause 15.6)

“Applied to IPR it means that it is not possible on technical (but not commercial) grounds, taking into account normal technical practice and the state of the art generally available at the time of standardization, to make, sell, lease, otherwise dispose of, repair, use or operate EQUIPMENT or METHODS which comply with a STANDARD without infringing that IPR.”

Definition of a SEP

“A patent which protects technology which is essential to implementing a standard is known as a standard essential patent”.

IPO definition at Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) explained.

The IPRs that are part of a final standard will then usually become available for licensing. This is often ensured by the SDO seeking a voluntary commitment from a SEP owner to license its SEPs on a FRAND basis. The relevant SDOs’ IPR policy will set out the various options for licensing of SEPs. SEPs licensing is further discussed in the ‘SEP licensing’ guidance.

3. Key technology areas where standards are used

Many standards do not include the use of patented technology but especially in telecommunication and consumer electronics you will find SEPs in:

- Telecommunications: SEPs in telecommunications involve technologies related to wireless communication standards such as GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications or 2G), UMTS (Universal Mobile Telecommunications System, or 3G), LTE (Long-Term Evolution, or 4G), (and sub-sets such as LTE-M and NB-IoT) 5G (Fifth Generation), Zigbee, Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11), Bluetooth, Ethernet, Wi-Max, Digital Subscriber Line (DSL)

- Digital Video and Audio Compression: SEPs in digital video and audio compression, used in digital broadcasting, streaming media, video conferencing, consumer electronics and multimedia applications, include technologies such as MPEG-2 (Moving Picture Experts Group), MPEG-4 Visual (Part 2), AVC/H (Advanced Video Coding), HEVC/H.265 (High Efficiency Video Coding), Opus (audio coding) and AAC (Advanced Audio Coding)

- Consumer Electronics: SEPs in consumer electronics cover standardised technologies used in devices such as smartphones, tablets, smart TVs, digital cameras, and gaming consoles, including wireless charging (Qi standards)

- Automotive: SEPs in the automotive industry encompass technologies related to vehicle communication, braking control systems (CAN), autonomous driving connectivity, navigation systems, telematics, driverless cars, and electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure

- Healthcare and Medical Devices: SEPs in healthcare and medical devices cover technologies such as medical imaging, diagnostic equipment, patient monitoring systems, electronic health records, and medical sensors such as insulin monitors.

- Semiconductors and Electronics: SEPs in semiconductors and electronics include technologies related to integrated circuits (ICs), semiconductor manufacturing processes, memory devices, power management, and sensor technologies

- and many more such as defence, industrial connected machinery, robotics, security, smart homes and smart cities (such as utilities), space / aeronautical

4. The disclosure and declaration process at Standard Development Organisations (SDOs)

A disclosure informs an SDO of specific patent(s) that the patent holder believes may become essential to the implementation of a standard. The terms “disclosure” and “declaration” are sometimes used interchangeably, and are sometimes used to refer to different concepts, although the distinction may not always be clear. ETSI defines “Disclosure” and “Declaration” as distinct concepts, and that distinction is adopted in this guidance (please refer to Clause 4, 6 and 6b in the ETSI IPR policy):

Explanation of disclosure and declaration ETSI IPR POLICY

“A disclosure informs an SDO of patents and other IPR that may be or become essential to the relevant standard.”

“A declaration” refers to a commitment by a patent owner that ensures their patent is available for implementation of a standard”.

Some, but not all, SDOs require participants in standardisation to disclose patents they believe are potentially essential to the standard. In many technical standards the number of SEPs is substantial and at the time of the disclosure the exact content of the final standard is not yet known, and the patent may not yet have been granted and its scope not finalised.

When the standard is finalised, many disclosed SEPs may not be essential. This may lead to what is commonly referred to as ‘over-declaration’.

Specific disclosure and blanket disclosure

Some SDOs require specific disclosure statements which list one or more patents (or pending applications) whilst others either require general disclosures (also referred to as blanket disclosures) covering any IPR essential to their standards through the terms of their IPR rules/policies. They may also allow general patent disclosure statements, which means the participant believes they may own IP relevant to a standard without identifying information about specific patents or patent applications. It is harder to evaluate the number, scope, and value of disclosed SEPs under a blanket disclosure because there is less information readily available.

The declaration commitment

‘Declaration’ refers to the commitment of a patent holder to make their technology available for implementation. Often SDOs require that this means providing licences to SEPs on Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) terms. The specifics of this commitment may differ from SDO to SDO globally.

ETSI, for example, has a “positive” declaration process, meaning that its members are only bound to the licensing commitment in respect of a disclosed patent, when they provide a declaration to ETSI covering a particular standard and specified IPR. Some other SDOs operate a ‘blanket declaration’ system, automatically binding their members to the licensing commitment, unless a member notifies the SDO to the contrary.

Some steps you may take to determine a SEP’s essentiality are described below, but in the absence of a determination by a court, there is no definitive way to determine whether SEPs are truly essential and will remain essential to a particular standard during the lifetime of the patent. This is taken into account during commercial negotiations, and is further discussed in the Licensing of SEPs Guidance section 4.1.

Some SDOs have databases of these disclosed SEPs. Please refer to the List of SDOs for further information. This table will include the following examples, and others;

- the European Telecommunications Standards Institute ‘ETSI’ has a public database that allows users to search for disclosed SEPs and owners of those rights, along with any licensing commitment that has been provided. See the Search IPR declaration (etsi.org) webpage for more detail

- ITU-T also has a public database to search for disclosed SEPs and owners of those rights. See the ITU-T Recommendations only Patent Statement webpage for more information

4.1 How do you find out if a disclosed SEP is truly ‘essential’?

The determination of essentiality is complex. If an implementer of a standard considers that a patent which has been disclosed as a SEP is not in fact essential to the implementation of the standard and believes that it can implement the standard on an unlicensed basis without infringing the patent, it will run the risk of the SEP owner bringing a claim for infringement if it does implement the standard without a licence. In those circumstances, essentiality can ultimately be determined by a court. See the guidance on dispute resolution and remedies in SEP licensing for further information.

Courts will often first evaluate the validity of a patent (i.e., is it novel and inventive), and may evaluate whether it is enforceable. An essentiality assessment will require technical and legal analysis by experts in the field.

The process for potential licensees to assess essentiality may involve the following steps:

1. Identify the relevant standard(s) or subset of standard: identify the standard to which the patent is claimed to be essential and then identify the relevant sub-set of the standard (if appropriate). This will involve reviewing relevant technical specifications for that standard identified by the patent owner.

2. Claim mapping: the claims of a patent can then be mapped against the technical standards’ specification. This will involve analysing the language and scope of the claims in a patent to decide if they cover the technology standard claimed by the SEP holder covered by their SEP. A SEP owner usually provides information such as claim charts, which map the claims in the patent to relevant aspects in the technical specification(s) for the standard. If they have not been provided, a potential licensee can and should request them. This step includes technical and legal analysis, and expert advice is often required. See Annex 1 for examples of claim charts.

3. Infringement analysis: to analyse whether the patented technology is used in the product or process which is implementing the standard. For example, the product or process may not use optional portions of the standard or may implement the standard in a manner different to those specified in the standard. Those differences may mean that the product or process, whilst capable of implementing the standard, does not fall within the scope of the SEP. Claims mapping comparing the claims of the patent against the product or process will also be required to establish infringement. This may require technical and legal analysis, and expert advice.

4. In some cases, third party assessments and expert input:

- when a patent becomes part of a licensing platform (e.g., a patent pool) it may undergo assessment by an independent expert. In patent pools this is mainly concerned with verifying the essentiality of the patent to the standard and not with verifying the validity of the patent because there is an assumption that the patent is valid

- experts can help provide a non-binding opinion on whether some aspects of the standard are implemented, and therefore whether a licence is actually required, as well as the assessment of essentiality

Expert input may also be required to assess the significance of the patent in relation to the standard, which is also related to valuation of the patent and not essentiality.

Ultimately, when there is a dispute over whether a patent is valid and infringed, courts or arbitration panels will decide the issues (including essentiality) and will rely on the evidence of technical subject-matter experts to help them determine the issues in dispute. More information on ADR and court processes can be found in the dispute resolution and remedies in SEP licensing guidance.

5. SDOs’ Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) policies

Intellectual Property Rights

“Intellectual property refers to creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; designs; and symbols, names and images used in commerce.”

IP is protected in law by, for example, patents, copyright and trademarks, which enable people to earn recognition or financial benefit from what they invent or create. By striking the right balance between the interests of innovators and the wider public interest, the IP system aims to foster an environment in which creativity and innovation can flourish.

(WIPO What is Intellectual Property? (wipo.int))”

IPR policies play a critical role at SDOs to ensure access to and use of their standards (also see “SEP Licensing Guidance” for more detail). SDOs therefore have rules governing how their members’ IP rights are assigned or licensed. These are usually referred to as IPR policies. IPR policies of SDOs govern how patents, copyrights, and other intellectual property rights are managed in the standards-setting process. These policies aim to encourage innovation by making sure that technologies are available as soon as possible for implementation and to ensure there is fair reward for the investment in standardisation by rightsholders.

Each SDO has its own rules and procedures, which often turn on the type of technology that is developed. This guidance is not intended to interpret any specific SDO policy.

Not all SDOs require participants to license their patents, or even disclose the IPR that is created during the standardisation process and believed to be essential to the implementation of a standard process. Some SDOs, such as the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), provide for royalty free licensing. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), another SDO, does not require participants to disclose their patents that are part of the standard. The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) does not have a licensing commitment, but rather expects participants to provide their own assurances of the accessibility of SEPs.

Some examples of IPR policies are as follows:

- ETSI - Intellectual Property Rights policy and IPR online database

- IEEE SA - Policies and Procedures; IEEE - IEEE Intellectual Property Rights; guidelines and policies on all aspects of IEEE intellectual property rights for authors, readers, researchers and volunteers

- Policies & Procedures - DVB (see Article 14 of the DVB Memorandum of Understanding)

- ISO/IEC/ITU-T: Common Patent Policy: Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC)

- IETF; IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force and https://www.ietf.org/blog/whats-behind-bcp79bis/)

Where an SDO has a Patent Policy, it should be checked if it also has a Copyright Policy which deals with copyright in the SDO standards, member contributions, and software. For example, if the standard is to be implemented in hardware, this is usually done through the use of software. Implementation of the software does not remove the need to check whether a licence is needed.

Most SDOs have IPR policies that ask their members to voluntarily commit to license their SEPs to future implementers of the standards on Fair, Reasonable, and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) or ‘FRAND’ terms. The terms RAND/FRAND are sometimes used interchangeably. A full explanation of “Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory” is provided in the SEP Licensing guidance at Section 1.2.

FRAND is a concept that aims to ensure that licences for all IPRs for a given standard are available on certain conditions. Adhering to FRAND licensing principles is crucial for maintaining a balance between incentivising innovation through patent protection and making sure that these patented technologies are available. IPR policies of SDOs aim to ensure that technical standards are implemented quickly so that consumers can buy products with standardised technology embedded in them, at reasonable prices.

However, the actual licensing terms are negotiated between individual parties, or via patent pools. The commercial terms of a royalty free standard are sometimes agreed by the SDO and members (e.g. Bluetooth, or Opus video codecs). Deciding on commercial terms and facilitating SEP licensing falls outside the remit of an SDO.

6. An overview of SDOs of interest to UK businesses

As detailed above, the standardisation process is developed within relevant standardisation bodies. There are many hundreds of SDOs across the world. These work at different levels, including national, European, and international:

National:

- British Standards Institution, is the national standards body of the UK

European:

- CEN is the European committee for standardisation. It develops and promotes general European standards together with its 34 members and other European and international partners.

International:

- ISO is the international organisation for standardisation and worldwide standards.

Technology specific examples:

- CENELEC is the European standardisation committee for electrotechnical standards, responsible for standards development in the field of electrical engineering

- ETSI is responsible for European standards in telecommunications, many of which have global use.

- 3GPP develops global mobile telecommunications standards (3GPP is not strictly speaking an SDO but a partnership of 7 regional SDOs, including ETSI, and also ATIS, ARIB, CCSA, TSDSI, etc)

- IEC is the international standards committee for electrical, electronic and related technologies

- ITU-T develops international standards in telecommunications

- ITU-R develops international standards related to radio and spectrum

- IEEE SA undertakes standards work for electrical, electronic and computing

- IETF develops standards work related to the internet

6.1 Participation in standard development

Participating in standard development involves engaging with SDOs and contributing to the creation and continued development of technical standards. There are ways a company (whether a SEP holder, an implementer (or both), or other interested party) can actively participate in standard development processes. These include:

- identify relevant SDOs: Research and identify SDOs that are relevant to your industry or the technologies you work with. Examples of SDOs are provided in the table

- join as a member: Consider becoming a member of the SDOs that are most relevant to your business interests. Membership may provide access to working groups, meetings, and voting rights on standardisation matters. Carefully consider the IPR Policy of the SDO and whether you are willing, if required by the SDO, to commit and undertake to license your IPR on their terms. With some SDOs membership is free, in others they are often reduced for small companies; however, fees may still be a barrier for some

-

participate in working groups: Get involved in working groups or technical committees within the SDOs. These groups are responsible for drafting, reviewing, and revising technical standards. Active participation allows your company to contribute its expertise and influence the content of standards

- contribute technical expertise at a working group: Consider whether to share your company’s technical knowledge, research findings, and practical insights with other members of the SDOs. Contributions can take the form of white papers, presentations, test data, or proposed specifications or changes to specifications. Ensure that you consider the impact of sharing your trade secrets or confidential information, consider filing patents for your inventions before contributing them to an SDOs’ work or sharing them with competitors, even under NDA. The IPO provides guidance and template documents for using a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). Consider obtaining legal advice as anything disclosed at an SDO amounts to prior art. More detail on this can be found in the SEP licensing guidance

- engage in consensus building in the process of participating in a working group: Work collaboratively with other stakeholders to reach consensus on technical standards or participate as an observer. This may involve negotiating differences of opinion, resolving conflicting interests, and finding compromises that benefit the industry as a whole -

assess the value for your work: Standards work can be valuable for your business, but it can also be very resource intensive. You should understand the policies and processes of the SDOs, their significance, potential impact on your business, and any cost implications. A lot of standards work can be done online, whereas some routes require physical attendance and travel

- staying informed: standards and standardisation: Keep up to date on developments in standardisation activities within your industry. Attend meetings, conferences, and seminars organised by SDOs to stay informed about emerging standards, trends, and best practices. Understanding these may help your business and product development

Further information on standards and standardisation can be found here:

- overview of SDOs of UK interest

- British Standards Online (theiet.org)

- Business & IP Centre (BIPC) open as usual The British Library (bl.uk)

-

Innovate UK Business Growth

- refer to Innovate UK for business support for innovative businesses who want to commercialise and grow - UK Telecoms Innovation Network (UKTIN): UKTIN Standards Expert Working Group UKTIN

- UKTIN support SMEs looking to innovate within the telecoms supply chain and navigate the standards ecosystem

7. Further IPO SEPs Resource Hub Guidance

- Introduction

- SEP Licensing

- Dispute resolution and remedies in SEP licensing

- International Signposting

- UK SEPs Case Law

- Glossary of terms

Intellectual Property Office and further support:

-

IPO Customer Support Centre: 0300 300 2000 / Email: Information

-

World Intellectual Property Office WIPO: WIPO Strategy on Standard Essential Patents 2024-2026

8. Disclaimer

The information on the SEPs Resource Hub is for guidance purposes only and does not constitute legal, business, financial or other professional advice and should not be relied upon when taking IP related business, legal or other decisions. The IPO is not responsible for the use that might be made of this information. Appropriate professional advice should be sought. The SEPs Resource Hub is not a substitute for proper legal advice. Every effort is made to ensure that the information provided is accurate and up to date as at the time of publication, but no legal responsibility is accepted for any errors or omissions.

The IPO provides guidance on how to find Specialist and Legal IP Support in the Seeking intellectual property advice webpage.

9. Annexes

Annex 1 Example of a claim chart

Empty claim chart template

| Claim number | Standard document and version | Relevant section(s) in the standard document |

|---|---|---|

| Example: | ||

| Claim 1 | TS99.888 V9.3.1 | §4.3.1, §4.3.2, Figure 2-1 |

Below is an annotated claim chart for an example patent A (note the level of detail of the claim charts provided may differ between charts).

| Patent A | Standard TS99.888 |

|---|---|

| Claim 1: A mobile telecommunications device comprising functions A, B and C | A UE shall include function A, function B and function C. |

Essentiality assessment: the standard requires that a UE includes A, B and C, and thus it is not possible to make a UE conforming to the standard without necessarily infringing patent A. Hence, patent A is essential to the standard.

Patent-side scoping

| Patent B | Standard TS99.888 |

|---|---|

| Claim 1: A base station device comprising functions A, B and C | A UE shall include function A, function B and function C. |

Essentiality assessment: the standard requires that a UE includes A, B and C. Yet, the scope of the patent only covers base stations that comprising functions A, B and C. Hence, the patent is not necessarily infringed by implementing (this part of) the standard. Hence, patent B is not essential to the standard.