UK-built spacecraft captures closest ever images of the Sun

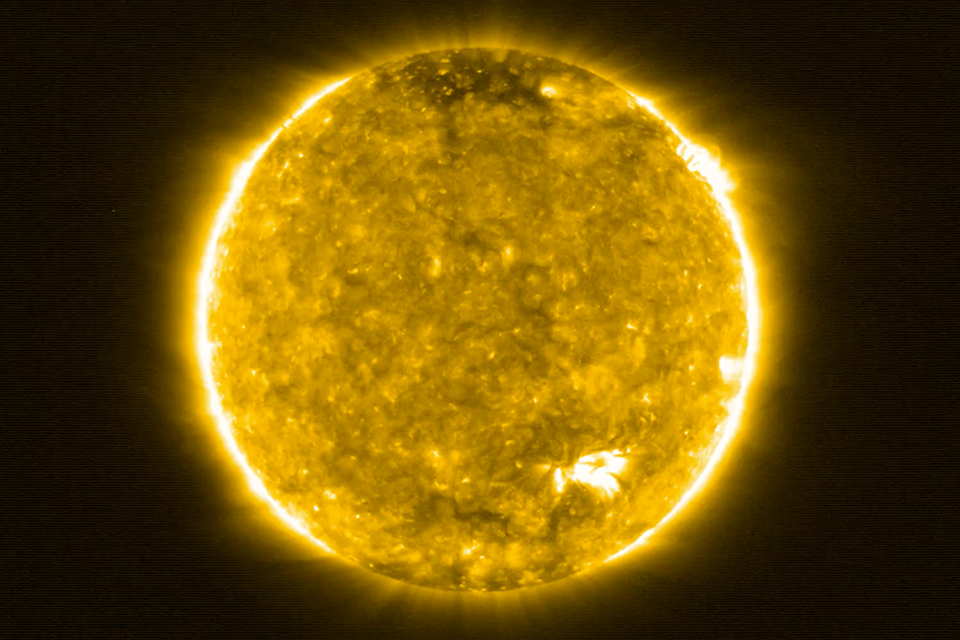

The closest images ever taken of the Sun, captured by the UK-built Solar Orbiter spacecraft, have been released today (Thursday 16 July).

Solar Orbiter/EUI Team (ESA & NASA); CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD/WRC, ROB, UCL/MSSL

Built in Stevenage by Airbus, backed by the UK Space Agency and launched in February 2020, Solar Orbiter will provide images of the Sun from inside the orbit of its nearest planet, Mercury, closer than ever before.

This week’s images and data come from its first close pass of the Sun in mid-June and early operations of the instruments.

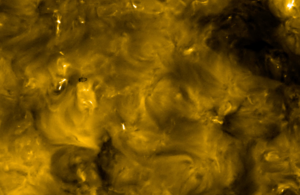

Recorded at a distance of just over 77 million kilometres, they have revealed omnipresent miniature solar flares, dubbed “campfires”, near the surface of the Sun. The close pass, known as a perihelion, puts the probe between the orbits of Venus and Mercury, the closest planets to the Sun.

These discoveries will help scientists piece together the Sun’s atmospheric layers – knowledge that is vital for our understanding of how it drives space weather events, which can disrupt and damage satellites and infrastructure on Earth that our mobile phones, transport, GPS signals and the electricity networks rely on.

Science Minister Amanda Solloway said:

The Solar Orbiter was eight years in the making, and represents an incredible feat of UK engineering. Now, this spacecraft has helped us make this historic discovery of the ‘campfires’ near the surface of the Sun.

This mission is one of the UK’s most important space ventures for a generation and, with our £600 million investment in international space science missions, I hope it will be one of many in the years to come.

Space weather

Occasionally, the Sun erupts giant amounts of particles known as coronal mass ejections. When such an eruption slams into Earth’s magnetic field, it generates surges of electrical current.

Solar scientists do not have reliable ways to predict such an eruption. The largest one known to hit Earth was the Carrington event in 1859, named after one of the people who observed an intensely bright spot on the Sun where the eruption occurred. The surge caused some telegraph wires to catch fire.

A similar event today could potentially cause not only continentwide blackouts, but also destroy giant transformers on the electric grid — damage that might take months or years to repair.

Satellite services such as communications, navigation and Earth observation supporting wider industrial activities are worth £300 billion to the UK economy, and this mission through discoveries like ‘camp fires’ could herald breakthroughs that help protect this infrastructure.

UK involvement

Solar Orbiter/EUI Team (ESA & NASA); CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD/WRC, ROB, UCL/MSSL

The UK played a key role in development of the Solar Orbiter mission. It provided funding for four of the 10 scientific instruments on board, and researchers from Imperial College London and the UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory (UCL MSSL) lead the teams behind Solar Orbiter’s Magnetometer (MAG) and Solar Wind Analyser (SWA) respectively.

UCL also has a key role in the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, which will enable the scientists to study processes on the Sun in greater detail than ever before. The Science and Technology Facilities Council’s (STFC) RAL Space led the consortium that developed and built the extreme ultraviolet imaging spectrometer (SPICE).

The campfires shown in the first image set were captured by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager around Solar Orbiter’s first perihelion, the point in its elliptical orbit closest to the Sun. At that time, the spacecraft was only 77 million kilometres away from the Sun, about half the distance between Earth and the star.

Dr David Long (UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory), Co-Principal Investigator on the ESA Solar Orbiter Mission EUI Investigation, said:

No images have been taken of the Sun at such a close distance before and the level of detail they provide is impressive.

They show miniature flares across the surface of the Sun, which look like campfires that are millions of times smaller than the solar flares that we see from Earth. Dotted across the surface, these small flares might play an important role in a mysterious phenomenon called coronal heating, whereby the Sun’s outer layer, or corona, is more than 200 - 500 times hotter than the layers below.

We are looking forward to investigating this further as Solar Orbiter gets closer to the Sun and our home star becomes more active.

It is not yet clear what these campfires are or how they correspond to solar brightenings observed by other spacecraft. But it’s possible they are ‘nanoflares,’ tiny but ubiquitous sparks theorised to heat the Sun’s corona, or outer atmosphere, to its temperature 300 times hotter than its surface.

To know for sure, scientists need a more precise measurement of the campfires’ temperature. Fortunately, the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment, or SPICE instrument, also on Solar Orbiter, does just that. RAL Space led the large international consortium to design and build the SPICE instrument and has been responsible for commissioning the instrument since launch.

Dr Andrzej Fludra, the SPICE Instrument Consortium lead and a Co-Principal Investigator from STFC’s RAL Space said:

We are delighted to see the first spectra and images from SPICE. They promise to solve the outstanding questions about the dynamic processes and composition of the Sun’s atmosphere.

Spectroscopy is a powerful tool for the diagnostic of fundamental processes in hot plasmas. Each spectral line gives us a piece of the puzzle – combining information from all lines reveals the amazing complexity of the atmosphere.

Today’s release highlights Solar Orbiter’s imagers, but its four in situ instruments also revealed initial results. In situ instruments measure the space environment immediately surrounding the spacecraft. Solar Orbiter’s Solar Wind Analyzer, or SWA instrument, shared the first dedicated measurements of heavy ions (carbon, oxygen, silicon, iron, and others) in the solar wind from the inner heliosphere.

Solar Orbiter is a space mission of international collaboration between the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA. The UK is at the heart of the mission with UK industry winning £200 million worth of contracts and the UK Space Agency investing £20 million in the development and build of the instruments.

Engineers at Airbus in Stevenage designed and built the spacecraft to withstand the scorching heat from the Sun that will hit one side, while the other is frozen as the orbit keeps it in shadow. It will face intense solar radiation that is 13 times more powerful than that in Earth’s orbit.

Principal Investigator Professor Tim Horbury from Imperial College London said:

Already our data are revealing shockwaves, coronal mass ejections, phenomena called ‘switchbacks’ and fine-scale waves in the magnetic field that we are only able to see thanks to the extreme sensitivity of our instrument.

Our small team of engineers here at Imperial College London have been working really hard to keep the instrument operating and process all the measurements that are coming down to the ground. Teams from around the world are now working on all this data, which will no doubt reveal new insights into the Sun’s behaviour.

The UK’s space sector is going from strength to strength, employing around 42,000 people and carrying out world-class science while growing the economy.

The UK continues to be a leading member of ESA, which is independent of the EU, having committed a record investment of £374 million per year in November 2019. This included £80 million on space safety and security for a mission in partnership with the US to protect infrastructure in space and on Earth from space weather and to help remove space debris.